Cetuximab was demonstrated by clinical trials to improve response rate and survival of patients with metastatic and nonresectable colorectal cancer or carcinoma of the head and neck. Appropriate management of skin toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy is necessary to allow adequate drug administration and to improve quality of life and outcomes. Interventions that were considered appropriate to improve compliance and outcomes of cancer patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor were identified.

Keywords: Cetuximab, EGFR, Italian Expert Opinions, Skin rash, Skin toxicity

Abstract

Background.

Cetuximab was demonstrated by clinical trials to improve response rate and survival of patients with metastatic and nonresectable colorectal cancer or carcinoma of the head and neck. Appropriate management of skin toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor (EGFR-i) therapy is necessary to allow adequate drug administration and to improve quality of life and outcomes.

Methods.

A group of Italian Experts produced recommendations for skin toxicity management using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Statements were generated on the basis of a systematic revision of the literature and voted twice by a panel of 40 expert physicians; the second vote was preceded by a meeting of the panelists.

Results.

Skin toxicity included skin rash, skin dryness, pruritus, paronychia, hair abnormality, and mucositis. Recommendations for prophylaxis and therapeutic interventions for each type of toxicity were proposed.

Conclusions.

Interventions that were considered appropriate to improve compliance and outcomes of cancer patients treated with EGFR-i were identified.

Introduction

Cetuximab (Erbitux; Merck-Serono, Darmstadt, Germany) is a human-murine chimeric monoclonal antibody directed to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) binding site [1–4]. Clinical trials on metastatic and nonresectable colorectal cancer and on carcinoma of the head and neck demonstrated improvement of response rate and survival after cetuximab treatment [5–14].

The major side effect associated with cetuximab treatment is skin toxicity, including skin rash, dry skin, hair growth disorders, pruritus, and nail changes [15, 16]. Cutaneous toxicity can severely impact patients' physical, psychological, and social well-being and can lead to treatment discontinuation and dose reduction. Therefore, appropriate management is necessary to allow adequate drug administration and to improve health-related quality of life and outcomes.

Interest in rash has recently increased because it was suggested to have a possible relationship with clinical outcomes [2, 13, 14, 17–27]. However, skin rash is not a useful criterion to distinguish patients with a better outcome because it is a very frequent adverse event with EGFR-targeting antibodies, and it occurs only after the exposure to these agents.

The agreement between oncologists and dermatologists in labelling and grading cutaneous lesions is poor, and interobserver inconsistencies are frequent [28]. As a consequence, the current terminology remains variable, and even the clinical features corresponding to the same terms, such as rash or acneiform rash or acnelike rash, are probably different across the trials.

Medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and dermatologists from Italy had a meeting in Rome on December 17–18, 2009, with the aim of reaching a consensus on clinical definition and management of cetuximab skin toxicity. In the absence of definitive evidence from clinical trials, they proposed recommendations on the basis of expert opinions developed by RAND Corporation/UCLA Appropriateness Method [29].

Consensus Method

The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method was used for this Consensus [29].

A group of expert clinicians (Advisory Board) performed a systematic review of the literature on cutaneous toxicity associated with EGFR inhibitor (EGFR-i) treatment of cancer patients. Considered issues included assessment of toxicity and benefits of different interventions in metastatic head and neck and colorectal cancer settings [30–43]. The MEDLINE database was searched for English-language studies that were published from 2005 to October 2009 and that contained the terms EGFR inhibitors, cetuximab, skin toxicity, skin rash, and/or radiation dermatitis in the title or abstract. Potentially relevant abstracts that were presented at annual meetings or gastrointestinal symposia of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the European Society of Medical Oncology were examined. The study selection included the following: (a) observational and prospective studies about assessment and treatment; (b) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, or uncontrolled studies; (c) retrospective and uncontrolled studies; (d) systematic reviews and meta-analyses; (e) consensus guidelines; and (f) available data for drugs tested in phase III studies (including abstracts).

On the basis of this literature review, the Board chose a number of key variables and generated clinical scenarios with permutations of these key variables. A wider group of panelists rated the appropriateness of treatment for each scenario through a two-round process. A meeting was held before the second rating, where statements were discussed. The final ratings were analyzed to identify aspects of skin toxicity for which the treatment was considered appropriate or inappropriate.

Consensus Panel

An Advisory Board of 9 expert members, from different clinical settings (6 medical oncologists, 2 radiation oncologists, and 1 dermatologist), was appointed, and a group of 40 panelists was identified. Each panelist and Board component had equal weight in scoring appropriateness of clinical scenarios.

Clinical Scenarios

A list of 107 common scenarios was provided by the Board, based on literature review. The interventions were categorized according to hypothetical situations or clinical scenarios based on combinations of various clinical factors. The clinical scenarios were then rated for each considered option.

First-Round Ratings

The first-round scenarios and the report of the systematic literature review were sent to the panelists. They were instructed to rate, independently, the appropriateness of treatment for each scenario without discussion with the other panelists. A scale of 1–9 was used, where 9 was defined as extremely appropriate (benefits greatly exceed risks), 5 was defined as uncertain (benefits and risks about equal), and 1 was defined as extremely inappropriate (risks greatly exceed benefits).

A treatment was appropriate if the expected health benefit exceeded the expected drawbacks and initiating the treatment was worthwhile. Panelists' ratings of the scenarios were collected online by the research team.

Second-Round Ratings

Panelists and Board discussed available evidence in a 2-day meeting, and then re-rated the appropriateness of the scenarios.

Analysis

Recommendations were scored appropriate for median ratings 7–9 (without disagreement), inappropriate for median ratings 1–3 (without disagreement), and uncertain for median ratings 4–6 or if panelists disagreed. Agreement was met when >1/3 of the scores were in the same range; disagreement was when <1/3 of the scores were in the same range. All other score distributions were defined as intermediate. Dedicated software was developed for statistical analysis of data.

Recommendations for Management during Chemotherapy

Clinical Features and Grading

Skin toxicities include skin rash, skin dryness (xerosis), pruritus, paronychia, hair abnormality, mucositis, and increased growth of the eyelashes or facial hair [15, 44–47].

Skin Rash

The most common toxicity is a papulo-pustular eruption, which affects 60%–80% of patients. It is generally mild to moderate, and it is severe (grades 3–4) in 5%–20% of patients [8, 48]. Incidence and severity are usually dose-related [44]. The rash is reversible, usually with complete resolution within 4 weeks of treatment discontinuation or sometimes during continued treatment; it may relapse or worsen at treatment restart [1, 49]. With long-term treatment, severity of rash may decrease [44].

The papulo-pustular eruption consists of erythematous follicular papules that evolve into pustules. Lesions may coalesce into plaques covered with pustules that dry and form yellow crusts [46]. In some cases, a seborrheic dermatitis-like pattern is seen on the face [1]. Rarely an edematous, warm erythema of the face, sometimes with follicular papulo-pustules and telangiectasia resembling rosacea, is seen. The eruption is acneiform and is usually confined to seborrheic areas; rarely it may involve the extremities, lower back, abdomen, and buttocks [46]. No comedones occur. In contrast to acneiform eruptions caused by other drugs, the rash may be accompanied by pruritus, sometimes severe. Cultures are negative for yeasts and bacteria. However, papulo-pustular lesion may become infected, usually with Staphylococcus aureus; then, oozing and yellowish crusts occur.

Skin Xerosis

Skin xerosis is present in up to 35% of patients receiving EGFR-i therapy and more frequent in patients undergoing gefitinib therapy [15, 50–53]. Xerosis develops over time and typically presents as dry, scaly, itchy skin, particularly in areas previously or simultaneously affected with the papulo-pustular eruption. Xerosis is often more widespread than the skin rash [50]. Some patients experience dryness of the vagina and perineum, causing discomfort on urination. The xerosis may evolve to chronic asteatotic eczema, with erythema and worsening of pruritus. Xerosis and eczematous changes at the fingertips, palms, and soles are associated with painful fissures.

Nail, Periungual, and Hair Toxicity

Nail and periungual toxicity occurs in 10%–20% of patients after several weeks to months of therapy and may present as acute paronychia (swollen and tender lateral nailfold), oozing, bleeding, and formation of granulation tissue leading to pyogenic granuloma-like lesions. Changes of the nails are common and include pitting, discoloration, and onycholysis, with partial or complete loss of nails. Most patients who develop nail or paronychial toxicities also experience follicular eruption. Cultures for bacteria and yeast are usually negative, but secondary infection is common. Nail changes can persist long after discontinuation of the EGFR-i [54]. Hair impairment can occur in up to 50% of patients and usually presents as either excess growth of the eyelashes and/or eyebrows (i.e., trichomegaly) or curly, wavy, fine, and brittle texture of facial hair and scalp hair. Hair toxicity usually occurs 2–5 months after the start of treatment and may resolve in weeks to months after treatment discontinuation [15].

Predictive Factors

Predictive factors for EGFR-i skin toxicity were not investigated. A retrospective study (published exclusively in abstract form) on a limited number of patients treated with erlotinib showed that a darker skin phototype was associated with reduced frequency and severity of skin toxicity [55].

Grading System

The most commonly used grading system for skin toxicity is the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 (NCI CTCAE v3.0) [56]. This classification, however, was not specifically designed to classify cutaneous side effects of EGFR-i therapy. Many of the skin signs included (e.g., vesicular eruption, bullae, exfoliation) are not associated with EGFR-i therapy. Moreover, in most patients, the eruption affects <30% of the body surface area (BSA), and the distinction between grades 2 and 3 is based on a 50% BSA involvement, which is very rarely seen if calculated accurately. A new version that distinguishes the diverse drug-related skin manifestations, including EGFR-i skin toxicity, has been released [56], but it is not widely used yet. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to define the area affected by a follicular eruption. Important factors not yet taken into consideration include the prevalent type (e.g., papular vs. pustular), the density (and thus the total number of lesions), and the infiltration of skin lesions. Local superinfection may not always be a relevant aggravating factor. Eventually, nail-related clinical features described in this grading scale do not reflect those typically seen in response to EGFR-i.

Wollenberg et al. proposed a new composite objective scoring system specific for the acneiform eruption, which considers the type of lesions and emphasizes the facial involvement, taking into account self-related symptoms [57]. Moreover, Lacouture et al. have recently presented a new grading scale specific to EGFR-i cutaneous toxicity. This grading system needs to be validated in future clinical trials [58]. A recent study on 80 patients treated with cetuximab showed that skin rash did not significantly affect some quality of life issues, such as psychological status or social life [59]. A correlation was found with psychological distress but not with social avoidance. Unfortunately, the type of skin rash was not defined. Instead, Joshi et al. reported a quality of life decrease in patients experiencing dermatological toxicities, and particularly rash. Both physical and psychological effects were directly related to skin toxicities. Moreover, patients <50 years had significantly lower quality of life than patients >50 years [60]. Further studies on the impact of skin toxicity to EGFR-i therapy on quality of life are warranted.

Management of Skin Toxicity (General Skin Toxicity)

General Prophylactic Measures

Before the start of cetuximab treatment, medical history and full-body skin evaluation should be performed, with attention to xerosis, atopic dermatitis, and severe acne vulgaris. Some educational and general interventions may be used:

Using sunscreens;

Avoiding habits/products that can produce dry skin (e.g., hot water, alcohol-based cosmetics);

Enhancing skin hydration (bath oils, etc.);

Using frequently alcohol-free moisturizing creams;

Using tocopherol oil or gel;

Avoiding tight shoes; and

Avoiding excessive beard growth, shaving with regular shaving razor, sharp multiblade; using pre-shaving cream emollients and moisturizing aftershave, not using alcohol and aftershave or using electric shaver.

Strategies for Single Type of Skin Toxicity

Skin Rash (Adapted from NCI-CTC Version 3) [56].

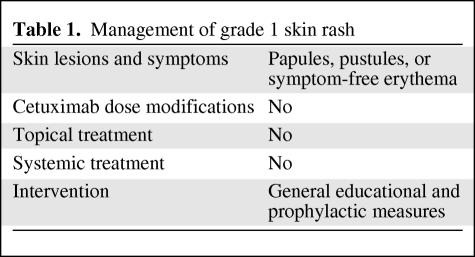

Grade 1: No dose modifications or treatment interruptions are indicated. No specific treatments should be started. Only general interventions are recommended (Fig. 1A and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Skin rash grades 1–4.

Table 1.

Management of grade 1 skin rash

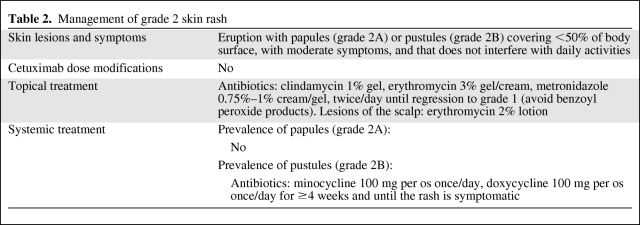

Grade 2: No dose modification or treatment interruptions are indicated. Topical antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 1% gel, erythromycin 3% gel/cream, or metronidazole 0.75%–1% cream/gel can be used 2 times per day until improvement to grade 1. Benzoyl peroxide should be avoided. For lesions of the scalp, erythromycin 2% lotion can be applied. When papules prevail (grade 2A), no systemic therapy is recommended. For pustule prevalent type (grade 2B), oral semisynthetic tetracycline (minocycline 100 mg/day, doxycicline 100 mg/day) can be used for ≥4 weeks and until the rash is symptomatic (Fig. 1B and Table 2).

Table 2.

Management of grade 2 skin rash

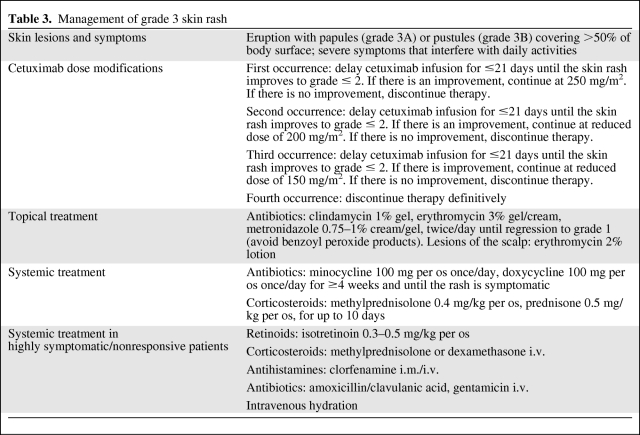

Grade 3: Interrupt treatment for ≤21 days, until improvement to grade ≤2. At improvement, if response to cetuximab had been obtained, continue EGFR-i therapy at full dose of 250 mg/m2. If no improvement occurs, discontinue therapy. For a second or third recurrence of skin rash, follow the dose modifications listed in Table 3. For a fourth recurrence, discontinue the treatment definitively. Topical treatment as for grade 2 can be used together with systemic therapy with oral semisynthetic tetracycline (minocycline, doxycicline) for ≥4 weeks and until the rash is asymptomatic, and oral corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 0.4 mg/kg, prednisone 0.5 mg/kg) for up to 10 days. For grade 3 highly symptomatic/nonresponsive patients, treatment with oral retinoids (isotretinoin 0.3–0.5 mg/kg), intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, dexamethasone), intramuscular/intravenous antihistamines (clorfenamine), intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, gentamicin), or hydration can be considered (Fig. 1C and Table 3).

Table 3.

Management of grade 3 skin rash

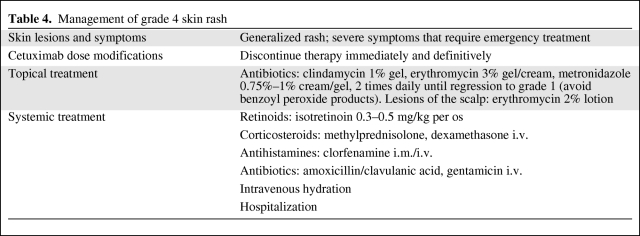

Grade 4: Interrupt EGFR-i treatment immediately and definitively. Provide topical treatment as indicated for grades 2 and 3. Consider systemic management with oral retinoids (isotretinoin 0.3–0.5 mg/kg), intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone, dexamethasone), intramuscular/intravenous antihistamines (clorfenamine), intravenous antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, gentamicin), and intravenous hydration (Fig. 1D and Table 4).

Table 4.

Management of grade 4 skin rash

Xerosis, Fissures, and Eczema.

General educational and prophylactic measures are important. The regular use of emollient ointments, almond oil, preparations of polyethylene glycol, is recommended. For eczema, topical treatment with medium-potency corticosteroids for 1–2 weeks can be used: betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%–0.1% cream, clobetasone 0.05% cream, ointment fluocinolone acetonide, or hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1% cream. Simple or occlusive dressing can be considered for the extremities. Topical antibiotic is recommended for superinfection: fusidic acid 2% cream, bacitracin cream, or mupirocin 2% cream.

Paronychia.

As a preventive intervention, it is necessary to avoid friction and pressure on the nail fold (avoid tight shoes). If paronychia develops, the following are suggested:

Washing with antiseptics: diluted hydrochloric acid solution or boric acid solution 3%;

Using creams containing corticosteroids and antiseptics: betamethasone 0.05% plus cliochinol 3% ointment, betamethasone 0.1% plus gentamicin 0.05% cream, betamethasone 0.1% plus gentamycin 0.1% cream, betamethasone valerate 0.1% plus fusidic 2% acid cream, triamcinolone acetonide 3% plus chlortetracycline 0.1% ointment, or triamcinolone benetonide 2% plus fusidic acid 0.03% cream;

Using oral antibiotics for superinfection: amoxicillin/clavulanic tablets, cefalexin tablets, or clindamycin capsules;

Using analgesic drugs (NSAIDs) per os.

Recommendations for Management during Radiotherapy

Management of Skin Toxicity (Radiation Dermatitis)

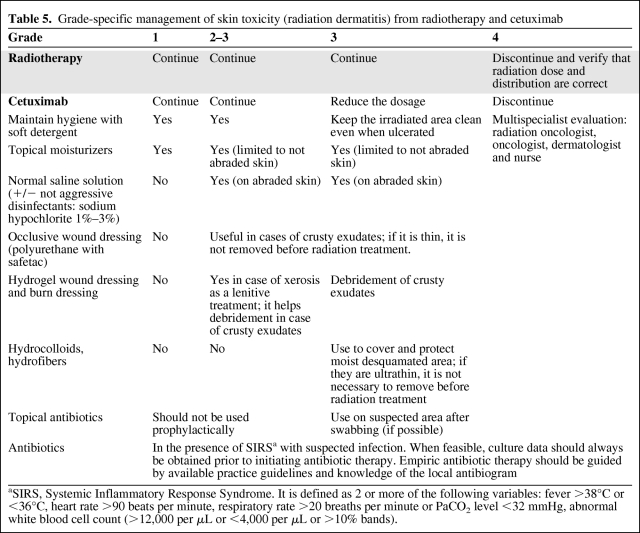

The recommendations for the management of general skin toxicity (different from radiation dermatitis) are the same as reported in the previous paragraph. Radiation dermatitis is modified by the introduction of EGFR-i in combination with radiotherapy. Leading principles according to the NCI CTCAE (version 3) grading of radiation dermatitis (Table 5) are as follows:

Skin toxicity, if well managed, does not necessitate discontinuation or dose reduction of EGFR-i therapy.

Treatment should be adapted to type of lesions, depending on time, patient condition, and location.

General recommendations for prophylaxis are similar to those for acnelike rash of nonirradiated skin [15, 43].

Cutaneous hydration should be achieved with creams or grease, with moisturizing factors (urea, lactic acid, and so on). Creams should be preferred to avoid greasy macerating effect in sweaty areas. Occlusive dressing (polyurethane with safetac) can be used to protect skin from microtrauma [61].

Debridement of crusts should be achieved with hydrogels [33, 62, 63].

Protect the desquamated areas with occlusive dressing (polyuretane) or burn dressing (hydrocolloids or hydrofibers). Hydrocolloids and hydrofibers contain carboxymethylcellulose (a gel-forming agent), inserted in an adhesive polymeric matrix. This agent absorbs exudates changing into gel and improves symptoms of intertriginous areas [35, 62, 63]. It manages pain very well but can favor maceration and delay healing.

Topical moisturizers, gels, emulsions, and dressings should not be applied shortly before radiation treatment to prevent a possible bolus effect, artificially increasing the radiation dose to the epidermis. Toward the end of the radiotherapy, if there are ulcerations, a thin burn dressing (hydrocolloid or hydrofibers) can be used during the treatment to avoid infections and trauma. A very thin dressing is recommended to avoid the bolus effect and permit the repositioning of the immobilizer mask.

Corticosteroids can be used in radiation dermatitis, but it is suggested that the overall treatment time be limited to <12 weeks [35].

Attention should be paid to pain relief.

When systemic impairment is suspected, monitor the presence of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) [64]. If SIRS is present and infection is suspected, culture should always be obtained before antibiotic therapy.

Table 5.

Grade-specific management of skin toxicity (radiation dermatitis) from radiotherapy and cetuximab

aSIRS, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. It is defined as 2 or more of the following variables: fever >38°C or <36°C, heart rate >90 beats per minute, respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute or PaCO2 level <32 mmHg, abnormal white blood cell count (>12,000 per μL or <4,000 per μL or >10% bands).

Recommendations for Clinical Organization

The Italian Experts agreed that a multidisciplinary management could minimize skin toxicities, limit the incidence of severe symptoms, improve patient compliance, avoid modification of prescribed therapies (radiotherapy and/or EGFR-i), and optimize outcomes [38]. No agreement was found about the composition of the multidisciplinary team that should deal with the issue.

Nonsevere skin reactions can be managed by trained nurses. Accordingly, in the Consensus Guidelines for management of radiation skin toxicity in head and neck cancer, the role of the nurse is essential for low-grade cases [30]. Referral to the dermatologist is recommended for grades 3–4 toxicity (in a survey, only 8% of patients obtained a dermatology consult [65]).

The presence of a wound specialist or a psychologist in the multidisciplinary team is recommended only for selected cases. Skin rash was not found to impact on patients' psychological status or social life, according to FACT-C (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Colorectal) and PDI (Psychological Distress Inventory), in patients with advanced colorectal cancer and treated with cetuximab-based therapy [59]. It was speculated that skin rash is considered as part of the suffering caused by cancer, and that patients are encouraged by oncologists to continue treatment because the skin rash is indicative of a therapy response.

A summary of Italian Experts recommendations is as follows:

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary.

A medical and a radiation oncologist should be in the team dealing with rash management when radiotherapy is used.

Trained nurses can manage low-grade skin toxicity.

Referral to the dermatologist is necessary when severe toxicity (grades 3–4) is present.

A wound specialist or a psychological consult are needed only in selected cases.

Conclusions

The introduction of cetuximab in colorectal and head-neck cancer therapy had a significant impact on outcomes. A strategic approach to the management of skin toxicity will allow one to limit the incidence of skin rash, to improve patients' compliance, and to optimize outcomes.

Nowadays, new topical agents are in development as potential therapy for rash: vitamin K, and in particular vitamin K1 (fillochinone) and K3 (menadione). Interesting evidence has been presented on the beneficial effect of vitamin K1 cream on patients experiencing severe acnelike rash, anti-EGFr induced [16,42,66–68].

The Expert Opinions reported in this article represent the Italian consensus derived from best clinical practices and the scientific literature available on the treatment of anti-EGFR skin toxicity. The large and increasing use of cetuximab in cancer treatment and the lack of specific clinical trials call for the development of medical research to hone a more accurate evaluation/grading and evidence-based treatment of skin toxicity.

Acknowledgments

The following oncologists, radiation oncologists, and dermatologists took part in the First Italian Expert Opinions on skin toxicity management associated with cetuximab treatment in combination with chemotherapy or radiotherapy: Chiara Abeni (Brescia), Daniela Adua (Rome), Giovanni Baldino (Sassari), Maria Chiara Banzi (Reggio Emilia), Rossana Berardi (Ancona), Feisal Bunkheila (Bologna), Angela Buonadonna (Aviano-PN), Franco Calista (Campobasso), Giacomo Cartenì (Naples), Michele Caruso (Catania), Mario Giovanni Chilelli (Viterbo), Domenico Cristiano Corsi (Rome), Renzo Corvò (Genoa), Agostina De Stefani (Treviglio-BG), Nerina Denaro (Messina), Concetta Di Blasi (Catania), Antonella Ferro (Trento), Giuseppe Fornarini (Genoa), Mario Franchini (Turin), Fabio Fulfaro (Palermo), Geppino Genua (Ariano Irpino-AV), Francesco Giuliani (Bari), Gabriele Luppi (Modena), Elena Magni (Milan), Andrea Mancuso (Rome), Mariangela Manzoni (Pavia), Gianluca Masi (Pisa), Cataldo Mastromauro (Mestre-VE), Renzo Mazzarotto (Bologna), Anna Mercanti (Verona), Mauro Minelli (Rome), Miriam Paris (Biella), Veronica Parolin (Verona), Ida Pavese (Rome), Lorenzo Pavesi (Pavia), Nicola Personeni (Rozzano-MI), Patrizia Racca (Turin), Monica Rampino (Turin), Enrico Ricevuto (Rome), Fabiola Lorena Rojas Llimpe (Bologna), Graziana Ronzino (Lecce), Antonino Savarino (Canicattì-AG), and Alessandro Tuzi (Rome). This work was supported by Merck-Serono-Italy, for technical assistance and organization of Meeting and Clinical Forum.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Carmine Pinto, Carlo Antonio Barone, Giampiero Girolomoni, Elvio Grazioso Russi, Marco Carlo Merlano, Daris Ferrari, Evaristo Maiello

Collection and/or assembly of data: Carmine Pinto, Carlo Antonio Barone, Giampiero Girolomoni, Elvio Grazioso Russi, Marco Carlo Merlano, Daris Ferrari, Evaristo Maiello

Data analysis and interpretation: Carmine Pinto, Carlo Antonio Barone, Giampiero Girolomoni, Elvio Grazioso Russi, Marco Carlo Merlano, Daris Ferrari, Evaristo Maiello

Manuscript writing: Carmine Pinto, Carlo Antonio Barone, Giampiero Girolomoni, Elvio Grazioso Russi, Marco Carlo Merlano, Daris Ferrari, Evaristo Maiello

Final approval of manuscript: Carmine Pinto, Carlo Antonio Barone, Giampiero Girolomoni, Elvio Grazioso Russi, Marco Carlo Merlano, Daris Ferrari, Evaristo Maiello

References

- 1.Rowinsky EK, Schwartz GH, Gollob JA, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and activity of ABX-EGF, a fully human anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3003–3035. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saltz LB, Meropol NJ, Loehrer PJ, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with refractory colorectal cancer that expresses the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1201–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zambruno G, Girolomoni G, Manca V, et al. Epidermal growth factor and transferrin receptor expression in human embryonic and fetal epidermal cells. Arch Dermatol Res. 1990;282:544–548. doi: 10.1007/BF00371951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pastore S, Mascia F, Mariani V, et al. The epidermal growth factor receptor system in skin repair and inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1365–1374. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Cutsem E, Lang I, Folprecht G, et al. Cetuximab plus FOLFIRI in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): The influence of KRAS and BRAF biomarkers on outcome: Updated data from the CRYSTAL trial. Paper presented at: Proc 2010 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; January 22–24; Orlando, Florida. abstract 281. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, et al. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2040–2048. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folprecht G, Gruenberger T, Bechstein WO, et al. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: the CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:38–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segaert S, Van Cutsem E. Clinical signs, pathophysiology and management of skin toxicity during therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1425–1433. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacouture ME. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baselga J, Trigo JM, Bourhis J, et al. Phase II multicenter study of the antiepidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody cetuximab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with platinum-refractory metastatic and/or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5568–5557. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenz HJ, Van Cutsem E, Khambata-Ford S, et al. Multicenter phase II and translational study of cetuximab in metastatic colorectal carcinoma refractory to irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and fluoropyrimidines. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4914–4921. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burtness B, Goldwasser MA, Flood W, et al. Phase III randomized trial of cisplatin plus placebo compared with cisplatin plus cetuximab in metastatic/recurrent head and neck cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8646–8654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berlin J, Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, et al. Predictive value of skin toxicity severity for response to panitumumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): a pooled analysis of five clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25 abstract 4134. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baselga J, Pfister D, Cooper MR, et al. Phase I study of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor chimeric antibody C225 alone and in combination with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:904–914. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tejpar S, Peeters M, Humblet Y, et al. Relationship of efficacy with KRAS status (wild type versus mutant) in patients with irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), treated with irinotecan (q2w) and escalating doses of cetuximab (q1w): the EVEREST experience (preliminary data) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 abstract 4001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lièvre A, Bacher J-B, Boige V, et al. K-ras mutations as an independnet prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:374–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peeters M, Siena S, Van Cutsem E, et al. Association of progression-free survival, overall survival, and patients-reported outcomes by skin toxicity and Kras status in patients receiving panitumumab monotherapy. Cancer. 2009;115:1544–1554. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orditura M, De Vita F, Galizia G, et al. Correlation between efficacy and skin rash occurrence following treatment with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab: a single institution retrospective analysis. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1023–1028. doi: 10.3892/or_00000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R, et al. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2171–2177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbst RS, Arquette M, Shin DM, et al. Phase II multicenter study of the epidermal growth factor receptor antibody cetuximab and cisplatin for recurrent and refractory squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5578–5587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffour J, Thézenas S, Dereure O, et al. Interobserver agreement between dermatologists and oncologists in assessing dermatological toxicities in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated by cetuximab-based chemotherapies: a pilot comparative study. Eur J Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.008. Published April 21, 2010;doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brook RH, Gompert DC. Rockville (MD): Public Health Service, AHCR; 1994. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method, “Clinical practice guideline development: methodology perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernier J, Bonner J, Vermorken JB, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of radiation dermatitis and coexisting acne-like rash in patients receiving radiotherapy plus EGFR inhibitors for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:142–149. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giro C, Berger B, Bolke E, et al. High rate of severe radiation dermatitis during radiation therapy with concurrent cetuximab in head and neck cancer: Results of a survey in EORTC institutes. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pryor DI, Porceddu SV, Burmeister BH, et al. Enhanced toxicity with concurrent cetuximab and radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russi EG, Merlano MC, Comino A, et al. Ultrathin hydrocolloid dressing in skin damaged from alternating radiotherapy and chemotherapy plus cetuximab in advanced head and neck cancer (G.O.N.O. AlteRCC Italian Trial) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:638–639. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skvortsova I. Oxidative damage and cutaneous reactions during radiotherapy in combination with cetuximab. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:281–282. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li T, Perez-Soler R. Skin toxicities associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Target Oncol. 2009;4:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s11523-009-0114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osio A, Mateus C, Soria JC, et al. Cutaneous side-effects in patients on long-term treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su X, Lacouture ME, Jia Y, et al. Risk of high-grade skin rash in cancer patients treated with cetuximab—an antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor: systemic review and meta-analysis. Oncology. 2009;77:124–133. doi: 10.1159/000229752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melosky B, Burkes R, Rayson D, et al. Management of skin rash during EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies: Canadian recommendations. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:16–26. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i1.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Racca P, Fanchini L, Caliendo V, et al. Efficacy and Skin Toxicity Management with Cetuximab in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Outcomes from an Oncologic/Dermatologic Cooperation. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:48–54. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segaert S, Tabernero J, Chosidow O, et al. The management of skin reaction in cancer patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor targeted therapies. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scope A, Liza A, Agero C, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of prophylactic oral minocycline and topical tazarotene for cetuximab-associated acne-like eruption. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5390–5396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ocvirk J, Rebersek M. Management of cutaneous side effects of cetuximab therapy with vitamin K1 crème. Radiol Oncol. 2008;42:215–224. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jatoi A, Green EM, Rowland KM, et al. Clinical predictors of severe cetuximab-induced rash: observations from 933 patients enrolled in north central cancer treatment group study N0147. Oncology. 2009;77:120–123. doi: 10.1159/000229751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agero AL, Dusza SW, Andrade CB, et al. Dermatologic side effects associated with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu JC, Sadeghi P, Pinter-Brown LC, et al. Cutaneous side effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busam KJ, Capodieci P, Motzer R, et al. Cutaneous side-effects in cancer patients treated with the antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibody C225. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1169–1176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braiteh F, Kurzrock R, Johnson FM. Trichomegaly of the eyelashes after lung cancer treatment with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3460–3462. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz G, Dutcher JP, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of ABX-EGF in renal cell cancer (RCC) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21 abstract 91. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial—INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:785–794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herbst RS, LoRusso PM, Purdom M, et al. Dermatologic side effects associated with gefitinib therapy: clinical experience and management. Clin Lung Cancer. 2003;4:366–369. doi: 10.3816/clc.2003.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimyai-Asadi A, Jih MH. Follicular toxic effects of chimeric antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibody cetuximab used to treat human solid tumors. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:129–131. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee MW, Seo CW, Kim SW, et al. Cutaneous side effects in nonsmall cell lung cancer patients treated with Iressa (ZD1839), an inhibitor of epidermal growth factor. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:23–26. doi: 10.1080/00015550310005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pérez-Soler R, Chachoua A, Hammond LA, et al. Determinants of tumor response and survival with erlotinib in patients with nonesmall-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3238–3247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fox LP. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lai SE, Minnelly L, O'Keeffe P, et al. Influence of skin color in the development of erlotinib-induced rash: a report from the SERIES clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25 abstract 9127. [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse event v. 2.0 1999, v. 3.0 2006, v. 4.0 2009. http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html.

- 57.Wollenberg A, Moosmann N, Klein E, et al. A tool for scoring of acneiform skin eruptions induced by EGF receptor inhibition. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:790–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lacouture ME, Maithand ML, Saegart S, et al. A propsed EGFR inhibitor adverse event-specific grading scale from the MASCC skin toxicity study group. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:509–522. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romito F, Giuliani F, Cormio C, et al. Psychological effects of cetuximab-induced cutaneous rash in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joshi SS, Ortiz S, Witherspoon JN, et al. Effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced dermatologic toxicities on quality of life. Cancer. 2010;116:3916–3923. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eriksen JG, Overgaard M. Late onset of skin toxicity induced by EGFr-inhibitors. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:280–281. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merlano MC, Russi EG. Epidermal Growth factor receptor-inhibitors and radiotherapy-induced cutaneous adverse effects: “Koebner-Phenomenon” or radio-dermatitis? Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:142–143. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mak SS, Lolassiotis A, Wan W, et al. The effects of hydrocolloid dressing and gentian violet on radiation-induced moist desquamation wound healing. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:220–229. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bone RC. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a unifying concept of systemic inflammation. In: Fein A, Abraham A, et al., editors. Sepsis and Multiorgan Failure. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 1997. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D, et al. Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology. 2007;72:152–159. doi: 10.1159/000112795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ocvirk J, Rebersek M. Topical application of vitamin K1 cream for cetuximab-related skin toxicities. Ann Oncol; Paper presented at: ESMO Conference: 11th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer; June 24–27, 2009; Barcelona, Spain. 2009. pp. vii22–vii23. abstract PD-0021. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ocvirk J, Rebersek M. Treatment of cetuximab-associated cutaneous side effects using topical application of vitamin K1 cream. J Clin Oncol; Paper presented at: 45th ASCO Annual Meeting; May 2009; Orlando, Florida. 2009. p. e15087. abstract e15087. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Radovics N, Kornek G, Thalhammer F, et al. Analysis of the effects of vitamin K1 cream on cetuximab-induced acne-like rash. J Clin Oncol; Paper presented at: 46th ASCO Annual Meeting; June 4–8, 2010; Chicago, Illinois. 2010. p. e19671. abstract e19671. [Google Scholar]