This review highlights the role of the progesterone receptor in breast cancer and discusses a significant subset of breast cancers that are estrogen receptor positive and progesterone receptor negative, and provides insight into the epidemiology, development, treatment concepts, prognosis, and resistance of these tumors to selective estrogen receptor modulators like tamoxifen.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor, Progesterone receptor, Growth factors, Gefitinib

Abstract

Estrogen receptor (ER)+ progesterone receptor (PR)− tumors are a distinct subset of breast cancers characterized by aggressive behavior and tamoxifen resistance in spite of being ER+. They are categorized as luminal B tumors and have greater genomic instability and a higher proliferation rate. High growth factor (GF) signaling and membranous ER activity contribute to the aggressive behavior of these tumors. The absence of PR is attributable to low serum estrogen, low levels of nuclear ER, and features of molecular crosstalk between GFs and membranous ER. PR expression is also downregulated by expression of mutated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII). This subset of patients has greater expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)-1 and HER-2 and active GF signaling mediated by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase–Akt–mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Currently, aromatase inhibitors, fulvestrant, and chemotherapy may be the favored treatment approaches for this subset of patients. Overcoming tamoxifen resistance with targeted therapies such as gefitinib is being evaluated and strategies involving short courses of tamoxifen have been postulated for prevention of recurrence of this subtype. Understanding the interplay between molecular endocrinology and tumor biology has provided experimental therapeutic insights, and continued work in this area holds the promise of future advances in prognosis.

Introduction

The management of breast cancer has moved very rapidly into the molecular era. The current approaches merge clinical, pathological, and molecular understanding of this tumor to allow a new grasp of outcomes and therapies affecting these outcomes. Most oncologists consider estrogen receptor (ER)+ tumors to be the best variant, with effective strategies to block, downgrade, or deprive the ER of its efficacy; human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)-2+ tumors to be next in line for malignant potential and management by HER-2–blocking therapies; and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) to be the worst category, because there are no targets to easily block even though newer approaches to use poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors seem promising. What is little realized is the fact that within the pantheon of ER+ tumors is the ER+ progesterone receptor (PR)− subtype, which has an outcome as bad as or worse than that of TNBC.

In this review, we highlight the role of PR in breast cancer and discuss a significant subset of breast cancers that are ER+PR−. We also provide insight into the epidemiology, development, treatment concepts, prognosis, and resistance of these tumors to selective estrogen receptor modulators like tamoxifen.

The ovarian steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone, respectively, control ductal growth and alveolar development in the normal mammary gland. They are believed to contribute to breast cancer development and progression. Response to endocrine therapy is related to the functional status of these receptors and not just their expression. In a normal maturing mammary gland epidermal growth factor (EGF) augments the proliferative effect of progesterone and estrogen to induce ductal side branching and lobuloalveolar development. EGF receptor (EGFR) family members are expressed in both normal and malignant breast epithelial cells, and their overexpression in breast cancer is predictive of a poor prognosis. EGFR promotes tumor progression, including invasion, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to treatment, by blocking apoptosis [1]. Crosstalk between EGFR and ovarian steroid hormone receptors continues in breast cancer cells [2]. The presence or absence of all these receptors contributes to tumor behavior and treatment outcomes.

Molecular Basis

Studying the molecular biology of receptors provides an insight into the mechanism of action of intracellular receptors, effect of antisteroids and other factors on receptor function, as well as the basis of cellular resistance to tamoxifen in breast cancer.

ER

ER plays a key role in normal breast development and breast cancer progression. It exists in two isoforms: ER-α and ER-β. Expression of ER-α is required for normal breast development, and a dramatic increase in ER-α is observed in premalignant lesions.

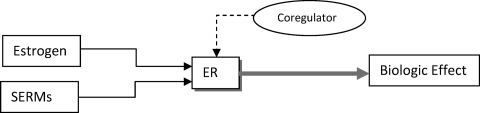

ER functions as a nuclear transcription factor. The action of estrogen in the nucleus is termed nuclear initiated steroid signaling (NISS). This transcriptional activity of ER is also known as classical or genomic ER activity [3]. ER action is controlled by coregulator proteins known as coactivators or corepressors [4]. ER binds to estrogen, recruits a coregulator complex, and regulates transcription of specific genes, such as PR, TFF1, GREB1, and PDZK1 (Fig. 1) [5]. The ability of tamoxifen to activate or repress ER is controlled by coregulators. When tamoxifen binds to ER, it recruits a corepressor to act as an antagonist. By altering the coregulators, tamoxifen can change from antagonist to agonist [4]. The agonistic activity of tamoxifen is enhanced in cells with more coactivators like amplified in breast cancer (AIB)-1 or steroid receptor coactivator 1 [3].

Figure 1.

Estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) bind to the estrogen receptor (ER) and recruit a coregulator complex to regulate transcription of specific genes.

Estrogen action on the plasma membrane is termed membrane initiated steroid signaling (MISS) [4]. MISS ER activity is also known as rapid, nongenomic, or nonclassical ER activity. A small pool of ER is located outside the nucleus in the cytoplasm or bound to plasma membrane [3]. This explains the short-term effects of estrogen (occurring within minutes) [3]. In cancers with low EGFR and low HER-2 expression levels, the membranous effects of estrogen are modest [3]. In cells in which EGFR, HER-2 and cytoplasmic proteins like metastasis-associated gene (MTA) are high, membranous effects are predominant because of sequestration of ER outside the nucleus [3]. Estrogen or tamoxifen binds to ER on the plasma membrane and activates growth factor receptors (EGFR and HER-2) and their downstream signaling pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. This leads to downregulation of PR and alteration of the apoptotic pathway, resulting in tamoxifen resistance [3, 4, 6]. Tamoxifen behaves as an estrogen agonist on MISS ER effects on membrane [3]. MISS contributes substantially to tumor growth and resistance to endocrine therapy and PR downregulation [3, 4].

A predominant switch from NISS to MISS ER activity explains the ER+PR− phenotype, because NISS ER activity causes transcription of PR whereas MISS ER activity causes PR downregulation. The MTA family of ER coregulators causes this switch. MTA-1 is a corepressor of genomic ER activity. MTA-1s is a naturally occurring variant that downregulates nuclear ER and also sequesters ER in the cytoplasm, thereby increasing MISS ER activity [4]. Hyperactive growth factor signaling shifts ER activity to act predominantly via MISS [4].

PR

PR is an ER regulated gene. The two isoforms of PR are PR-A and PR-B. PR is critical for lobuloalveolar development of the breast. An abundance of PR-A has been associated with an elevated risk for breast cancer [4]. A dramatically higher incidence of breast cancer was seen in women taking hormone-replacement therapy containing estrogen and progesterone in comparison with that containing estrogen alone. This raises the importance of progesterone in breast cancer [4]. PR serves as an indicator of a functionally intact nuclear ER pathway and helps predict which patients will respond to hormonal therapy, because adequate levels of estrogen and nuclear ER are required to transcribe PR [4]. PR also serves as an indicator of tumor aggression. Elevated PR levels indicate less aggressive tumors that are associated with a longer time to treatment failure and longer overall survival time in metastatic disease, whereas PR− tumors are more aggressive [4].

Loss of PR

There are various theories to explain PR downregulation and decreased expression of PR, leading to a subset of cancers that is ER+PR−.

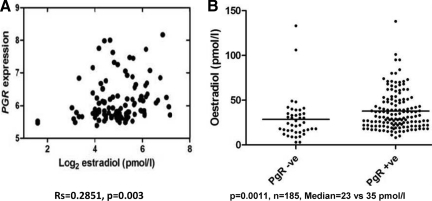

Although it is true that ER is nonfunctional in some of these tumors and is unable to stimulate PR production, and the tumor is no longer dependent on estrogen for growth and survival, some of these tumors may simply result from low circulating levels of estrogen in postmenopausal women that are insufficient to induce PR expression even though the ER pathway may be intact [4]. Studies have also shown a positive correlation between PR and plasma estradiol levels in postmenopausal women (Fig. 2) [5].

Figure 2.

Correlation between plasma estradiol and progesterone receptor levels in postmenopausal women with breast cancers. (A): Significant positive correlation between progesterone receptor (PR) and plasma estradiol levels in postmenopausal women. (B): Plasma estradiol levels are significantly higher in patients with PR+ tumors than in those with PR− tumors by immunohistochemistry. Reprinted from Dunbier AK, Anderson H, Folkerd EJ et al. Expression of estrogen responsive genes in breast cancers correlates with plasma estradiol levels in postmenopausal women. Presented at the 31st Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, Texas, December 13, 2008, with permission.

This theory does not completely explain the loss of PR in ER+PR− breast cancer because ER is transcriptionally active in some of these tumors [4].

Hypermethylation of PR Promoter or Loss of Heterozygosity at the PR Gene Locus

Another potential mechanism for loss of PR is downregulation of PR protein, which occurs at the level of PR mRNA and is dependent on an intact PR promoter. In 21%–40% of ER+PR− tumors, methylation of the PR promoter was seen, which could silence PR expression. A report suggested that activator protein 1 may be involved in repression of the PR promoter [4]. Even a genetic loss (loss of heterozygosity) of a PR gene locus (Ch11q23) causes loss of PR in breast cancer [4].

Growth Factor Pathway Downregulation of PR

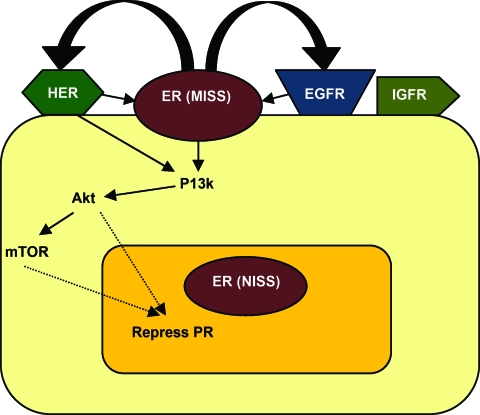

There are several lines of evidence suggesting molecular crosstalk between ER and growth factor signaling pathways that cause downregulation of PR protein levels [3, 4, 6]. Growth factors can also independently cause PR downregulation. HER-2 overexpression causes PR expression to be 500-fold lower, whereas ER expression is lower by half [4]. The expression of PR is lower in T47D breast cancer cells that overexpress HER-2 (PR expression in T47D cells is independent of ER) [4]. Short-term treatment (a few hours) with insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, EGF, and heregulin all sharply lower PR levels and progesterone-induced PR activity in breast cancer cells [4]. The activity of HER-2 results in cytoplasmic sequestration of ER and potentiates nonclassical ER signaling, which alters a set of genes that is normally regulated by ER [4]. Growth factors also activate the PI3K–Akt–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and downregulate PR levels (Fig. 3). Inhibitors of this pathway could reverse PR downregulation [4, 6].

Figure 3.

Greater growth factor signaling via the PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway and predominant MISS ER activity in ER+PR− tumors.

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; IGFR, insulin-like growth factor receptor; MISS, membrane initiated steroid signaling; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PR, progesterone receptor.

ER+PR+ tumors that become tamoxifen resistant are those with a more dramatic decrease in PR levels than in ER levels with tamoxifen therapy, making them ER+PR−. About half of these tumors completely lose PR expression and display a much more aggressive course after loss of PR [4].

Based on an immunoblot analysis model of MDA-361 human breast cancer cells, which are estrogen independent and tamoxifen resistant, a type III EGFR mutant (EGFRvIII) partially decreased the expression of ER and significantly decreased PR expression [6]. EGFRvIII expression is significantly correlated with a lack of PR and an aggressive phenotype. Expression of EGFRvIII in PR− versus PR+ tumors was 58% versus 39%, respectively (p = .01) [6].

Characteristics of ER+PR− Breast Cancer

ER+PR− breast cancer is a more aggressive phenotype and is resistant to tamoxifen. We discuss tamoxifen resistance later in this review. Clinically, these tumors are larger in size than ER+PR+ tumors (51% versus 45%; p < .001), and 19% had four or more axillary lymph nodes involved, compared with 16% of ER+PR+ tumors (p < .001) [7]. Some studies have shown that PR negativity predicts lymph node invasion, especially in younger patients, and is independent of other predictors like tumor grade and tumor size [8]. These tumors are more frequent in older patients [7]. The median level of ER in ER+PR− tumors is low, approximately half that in ER+PR+ tumors [7]. They also have a higher S-phase fraction, resulting in a higher proliferation rate, and are more likely to be aneuploid [7].

ER+PR− tumors show greater genomic instability and twice as many DNA copy number gains or losses as compared with ER+PR+ and ER−PR− tumors [9]. They showed copy number gains within regions 11q13 (68–72 Mb), 12q14-q15 (63–68 Mb), and 17q21-q25 (45–73 Mb), and copy number losses within regions 11q13-q25 (82–134 Mb) and chromosome 22 [10]. Analysis of DNA profiles indicated that there were patterns of copy number alterations that were more specific to and more frequent in ER+PR− tumors [10]. The gene expression profile was indicative of active growth factor signaling via the PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathway in these tumors [10].

ER+PR− tumors have high growth factor signaling [3, 4, 7]. They have higher levels of EGFR and HER-2 than ER+PR+ tumors [4]. ER+PR− breast cancers express HER-1 in 25% of cases, in comparison with 8% of ER+PR+ cases (p < .001) [7]. They overexpress HER-2 in 21% of cases, in comparison with 14% of ER+PR+ tumors (p < .001) [7]. In a report by Neven et al. [8], a negative association between PR and HER-2 was seen in women aged >45 years only, indicating that crosstalk is greater in older women. HER-1 expression and HER-2 overexpression are associated with a significantly shorter disease-free survival (DFS) interval in patients with ER+PR− tumors, whereas in ER+PR+ disease, neither HER-1 expression nor HER-2 overexpression is associated with DFS [7].

ER+ tumors, although highly heterogeneous, consist largely of tumors described as luminal. They are genetically distinct from ER− tumors.

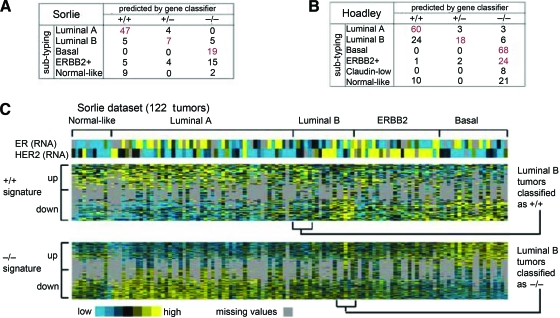

ER+PR− tumors defined by gene signature are associated with the luminal B subtype initially defined by Perou et al. [11], the amplifier phenotype subgroup defined by Chin et al. [12], and the ER+ and high grade tumors defined by the gene expression grade index of Loi et al. [13] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

ER+PR− tumors as defined by gene signatures associate with the luminal B breast cancer molecular subtype. (A): Confusion matrix for the tumor profile dataset from Sorlie et al. [33] comparing subtype assignments using the ER+PR+ and ER−PR− gene signatures with the molecular profile subtypes as defined previously by an unsupervised analysis. Red bold denotes a significant number of subtype assignments by the gene classifier within one of the Sorlie et al. [33] molecular subtypes (p < .001, one-sided Fisher's exact). (B): Confusion matrix for the profile dataset from Hoadley et al. [34]. (C): Heat map of the ER+PR+ and ER−PR− gene signatures (100 and 570 genes represented, respectively) in the Sorlie et al. [33] tumor profile dataset (gray, missing data values).

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

Reprinted from Figure 3 of Creighton CJ, Kent Osborne C, van de Vijver MJ et al. Molecular profiles of progesterone receptor loss in human breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;114:287–299, with permission from Springer.

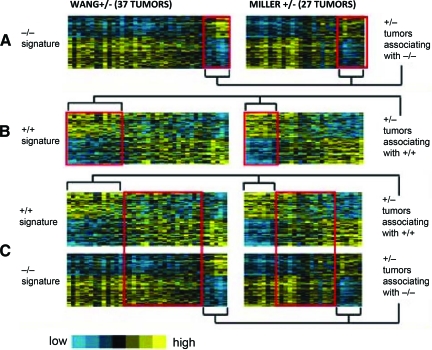

ER+PR− tumors represent a subtype that is distinct at a molecular level from ER+PR+ and ER−PR− tumors. These tumors are a mixture of three different molecular subtypes [9]: (a) a +/− tumor associating with a +/+ tumor by gene signature, (b) a +/− tumor associating with a −/− tumor by gene signature, and (c) a +/− tumor not aligned with either a +/+ tumor or a −/− tumor by gene signature (true ER+PR−) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Association between ER+PR− tumors and ER+PR+ and ER−PR− tumors by gene signature.

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor.

Reprinted from Creighton CJ, Kent Osborne C, van de Vijver MJ et al. Molecular profiles of progesterone receptor loss in human breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;114:287–299, with permission.

Epidemiology

Both age and menopausal status are correlated with an ER+PR− tumor status [4]. Sixty percent of these patients are >60 years old [14]. In patients with these tumors, the proportion of patients with a postmenopausal status is higher (32.8%) than the proportion of those who are premenopausal (23.1%) [14]. This is a result of ovarian shutdown in the elderly causing insufficient levels of estrogen to transcribe PR. A high body mass index (BMI) after menopause is positively correlated with ER+PR+ tumors but not with ER+PR− tumors [15]. This could be explained by the positive correlation between serum estrogen and PR levels after menopause. Because adipose tissue is one of the major sources of estrogen production after menopause, women with a low BMI after menopause have low serum estrogen levels, which favors the ER+PR− subset.

Other major factors positively associated with PR− tumors are high glycemic load diets, high glycemic index, and a high carbohydrate intake. Dr. Susanna C. Larsson of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and colleagues analyzed data on 61,433 women who completed “food frequency” questionnaires in the late 1980s. Over a period of 17 years, 2,952 women developed breast cancer, and the women with higher glycemic load diets were more prone to do so because of elevated insulin and insulin growth factor levels. These factors have potent positive effects on the development and spread of breast cancer cells. Patients with diets rich in high glycemic index foods (that cause a rapid surge in blood sugar, e.g., potatoes, bread) had a 44% greater risk for developing ER+PR− tumors than patients with diets rich in low glycemic index food (that cause a gradual increase in blood sugar, e.g., high-fiber cereals, beans). Women in the highest category of “glycemic load” had an 81% greater risk for ER+PR− tumors [16].

Tamoxifen Resistance

Response to tamoxifen has been shown to be directly related to ER levels; low ER levels in these tumors cause a lesser effect of tamoxifen [4]. One wonders why tamoxifen would not work on this cell type and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) would, especially if one believes that we are dealing with nonfunctional ER! Strands of work suggest an alternative narrative. Membranous ER signaling activates the cell survival pathway, protecting breast cancer cells from tamoxifen-induced apoptosis [4]. Tumors with high MISS ER activity would still be dependent on estrogen and therefore respond to its withdrawal with AIs. Also, in a mouse model cell line bearing MCF7/HER2–18 cells, which express ER, HER-2, and amplified coactivator AIB-1, tamoxifen behaved as an agonist and stimulated tumor growth whereas estrogen withdrawal strikingly demonstrated inhibition [4].

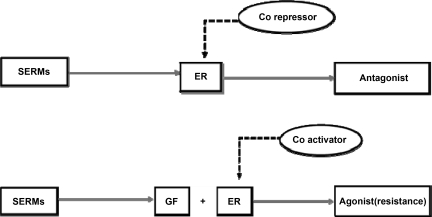

This may be a partial explanation for why high growth factor signaling in these tumors alters the coregulators that cause tamoxifen to change from an antagonist to an agonist and subsequent resistance (Fig. 6) [3, 4]. Studies have shown correlation between tamoxifen resistance and tumors with high EGFR and HER-2 levels, and the crosstalk between membranous ER and growth factors seems responsible for the agonist activity of tamoxifen [4].

Figure 6.

Growth factors cause tamoxifen to change from antagonist to agonist.

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; GF, growth factor; SERMs, selective estrogen receptor modulators.

There is also evidence implicating upregulated Akt in hormone resistance.

Prevent Loss of PR by Tamoxifen Treatment

A study was conducted wherein the NRL-TGFα mouse model closely simulated the ER+PR− growth factor positive phenotype that represents a subset of antiestrogen-resistant clinical breast cancers. Using this mouse model, it was shown that resistance to antiestrogen treatment was present in late-stage tumors. Furthermore, when tamoxifen was given to the mice prior to expected lesion development (for a 60-day period), there was a significant beneficial effect on tumor incidence and latency as well as hyperplasia characteristics several months later. There was a 50% lower tumor incidence in this model. The study suggests that prophylactic tamoxifen in high-risk patients might be helpful in reducing the incidence of ER+PR− clinical breast cancers [17]. The effect of tamoxifen chemoprevention on the incidence of clinical cases of ER+PR− breast cancer has not been determined. This information could open up new approaches to prevention and reduction in morbidity and mortality of breast cancer.

Management

Therapeutic Approaches

There are various therapeutic strategies directed at inhibiting the action of ER. Estrogen withdrawal is one that can be achieved by AIs.

Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination

In a hypothesis-generating analysis of the influence of receptor levels (as measured at participating institutions in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination study), Dowsett et al. [18] found that the superiority of anastrozole over tamoxifen was more marked in patients with ER+PR− tumors. PR levels in that trial were determined by local laboratory assessment [4, 9].

A subgroup analysis indicated that AIs may be more effective in patients with ER+PR− tumors. AIs produced a 52% lower risk for recurrence in patients with ER+PR− tumors and an 18% lower risk for recurrence in patients with ER+PR+ tumors, as compared with tamoxifen [14].

AIs should not be used in premenopausal women because estrogen withdrawal causes negative feedback on the pituitary, which results in surges of estrogen and increased breast cancer growth. In these cases, estrogen withdrawal can be achieved by surgical oopherectomy or ovarian ablation followed by AIs.

Breast International Group 1–98 Trial

In this trial, the ER and PR status were determined by immunohistochemistry [9]. It was found that patients treated with letrozole (an AI) had a better outcome than those treated with tamoxifen irrespective of their PR status; also, the level of PR was not predictive of tamoxifen benefit.

Although the results are inconsistent in these trials, the vast majority of the data suggests that greater growth factor signaling in these tumors causes tamoxifen resistance, in which case AIs are a good alternative. Hence, initial treatment with AIs is a reasonable rationale and may be most favorable.

Estrogen degradation with selective estrogen receptor downregulators, such as fulvestrant, which are a subclass of estrogen antagonists, can also be used [4]. Fulvestrant disrupts ER and HER-2 signaling. Resistance to AIs could occur as a result of the tumor becoming supersensitive to low residual estrogen concentrations, perhaps because of activation of MAPK. Such tumors respond to additional treatment with fulvestrant [3].

Alternative Treatment Strategies

Upregulation of growth factor signaling and crosstalk between growth factors and ER render ER+PR− tumors resistant to tamoxifen therapy. Clinically, it is crucial to block this crosstalk by inhibiting signaling networks to achieve optimal therapeutic activity [3]. This process can be delayed or reversed by inhibiting EGFR and ER signaling by simultaneous treatment with growth factor pathway inhibitors with endocrine therapy [19]. The strategies to inhibit growth factor signaling include mTOR inhibitors (everolimus, temsirolimus), PI3K inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, IGF receptor inhibitors, and EGFR inhibitors [20]. Combination of hormonal therapy with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (which is an orally active drug) caused suppression of growth factor pathways and led to replacement of coactivator complexes with corepressor complexes, which re-establishes the anatagonistic activity of tamoxifen [3]. In an experimental study in a mouse model bearing MCF-7/HER2–18 cells (ER+ and HER-2 overexpressed), simultaneous treatment with tamoxifen and gefitinib reduced growth factor signaling and, most importantly, blocked growth stimulation by tamoxifen by re-establishing its potent antagonistic qualities [3].

Similar results were seen in clinical trials. A phase II prospective, randomized, double-blind trial was conducted by Cristofanilli et al. [19] to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of anastrozole and gefitinib, compared with anastrozole plus placebo, in postmenopausal women with hormone-positive metastatic breast cancer and ER+ cancers that were tamoxifen resistant. There was a marked advantage in terms of the progression-free survival interval in patients treated with anastrozole plus gefinitib, compared with anastrozole plus placebo (14.7 months versus 8.4 months), and the clinical benefit rates were 49% and 34%, respectively [19]. These results are consistent with those from stratum 1 of a comparison of tamoxifen plus gefitinib or placebo by Osborne et al. [21]. Polychronis et al. [22] studied patients with ER+ EGFR+ primary breast cancer in the preoperative setting; patients were exposed for 4–6 weeks to gefitinib monotherapy or combination therapy with anastrozole. Both monotherapy and combination therapy were associated with a notable reduction in tumor size and Ki-67 activity [19]. Based on these sets of data, gefitinib seems to be promising in patients with these tumors, but clinical trials are warranted for the use of gefitinib with anastrozole, specifically in the ER+PR− subset of patients.

In a randomized neoadjuvant phase II study of postmenopausal women with ER+ breast cancer, the combination of letrozole plus everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) significantly decreased the tumor size (58% versus 47%; p = .03) and Ki-67 expression level after 15 days of therapy, to a greater degree than with letrozole alone [23].

Trastuzumab Plus Anastrozole Versus Anastrozole Alone

This trial was conducted in patients with HER-2+ hormone receptor–positive tumors in which increased crosstalk caused endocrine therapy resistance. It showed a longer progression-free survival duration with the combination than with anastrozole alone, but practical results were somewhat disappointing because of more serious adverse events with the combination [24].

ER+PR− tumors express higher levels of HER-1 and HER-2 and have greater growth factor signaling. Because HER-2 patients have a poor response to endocrine therapy, it is reasonable to administer trastuzumab or even chemotherapy to some selected group of these patients to improve prognosis [14].

Lifestyle Modifications

Women with ER+PR− tumors, when switched over to a healthy lifestyle, consisting of high fruit and vegetable consumption with high levels of physical activity, had significantly longer survival times than women consuming low levels of fruits and vegetables with low levels of physical activity (p = .04) [25].

Prognosis

ER+PR− tumors are associated with a poor prognosis. Comparisons were made between ER+PR− and ER+PR+ groups of patients who received adjuvant tamoxifen in different age group strata (<45 years, 45–60 years, >60 years).

There was no significant difference in terms of the DFS interval in ER+PR+ and ER+PR− patients <45 years old (p = .4) and 45–60 years old (p = .9). There was a significantly longer DFS interval in patients with ER+PR+ tumors than in those with ER+PR− tumors for patients >60 years old (p = .048) [14]. Such differences could be explained by greater EGFR crosstalk in older women.

The overall survival time was longer in patients with ER+PR+ tumors than in those with ER+PR− tumors for all age groups, but a clearer benefit was seen in older patients. There was a significantly greater benefit in terms of a longer OS time in patients with ER+PR+ tumors than in those with ER+PR− tumors for patients >60 years old (p = .0009), as compared with those <45 years old (p = .0102) [26].

Molecular profiling accurately predicts the prognosis of patients with these tumors. Patients with ER+PR− tumors designated by molecular profiling rather than a clinical assay (immunohistochemistry or biochemical assay) had a poorer prognosis. The poor outcome of the molecularly defined ER+PR− subset was at least as bad as that of patients with ER−PR− tumors [10]. They had the shortest time to recurrence, followed by those with ER−/PR− tumors.

Predictive/Prognostic Meaning of PR Loss in Metastatic Versus Primary Setting

Metastatic Setting

ER and PR positivity diminish with progression of disease. This almost always seems to happen in the direction of loss of positivity and never a gain, indicating tumor dedifferentiation. ER+PR− metastatic tumors display a much more aggressive course after loss of PR [4]. In the metastatic setting, PR loss is associated with shorter DFS and overall survival times, particularly with the use of quantitative analytic methods. ER+PR− tumors are associated with a poorer response to endocrine therapy than for ER+PR+ tumors [7, 27, 28]. Also, Elledge et al. [29] demonstrated a significant predictive value of PR for response to endocrine therapy in the metastatic setting.

Primary Setting

Similar to the metastatic setting, patients with PR− tumors derive less benefit from endocrine therapy in the adjuvant setting [7]. In the setting of primary breast cancers that are ER+, studies have shown that the absence of PR is an independent predictor of poor response to endocrine therapy, higher recurrence rates, and shorter survival times [30]. In a multivariate analysis on primary breast cancer patients, Bardou et al. [31] confirmed that PR was an independent predictor of response to endocrine therapy and that loss of PR was detrimental to the relative risk for recurrence (ER+PR+, 53%; ER+PR−, 23%). The loss of PR in primary breast cancer is associated with faster disease progression and a poorer response to endocrine therapy [32].

Hence, PR loss is linked to a poor prognosis and less benefit from tamoxifen in both the adjuvant and metastatic settings [28].

Future

Patients with hormone receptor–positive tumors are assumed to have a good prognosis, but different permutations and combinations of these receptors are associated with variable tumor behavior, as we have described for the ER+PR− subset. Thus, it is recommended to measure the levels of these receptors in all primary breast cancer specimens to predict disease outcome and tumor behavior, and to select appropriate adjuvant therapy. Tremendous progress has been made in the treatment of breast cancer. The knowledge of molecular endocrinology and tumor biology has advanced our understanding of the mechanisms of ER and estrogen action in these tumors and can lead to substantial improvements in treatment and prevention in the future. A short course of estrogen to restore PR levels can pave the way for the development of a preventive strategy for this aggressive phenotype and improve the prognosis, although selection of patients and timing of estrogen administration could be a challenge. Targeted therapies for this subtype seem promising and warrant further exploration.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Jigisha P. Thakkar, Divyesh Mehta

Financial support: Jigisha P. Thakkar, Divyesh Mehta

Provision of study material or patients: Jigisha P. Thakkar, Divyesh Mehta

Collection and/or assembly of data: Jigisha P. Thakkar

Data analysis and interpretation: Jigisha P. Thakkar, Divyesh Mehta

Manuscript writing: Jigisha P. Thakkar

Final approval of manuscript: Jigisha P. Thakkar, Divyesh Mehta

References

- 1.Nakamura Y, Oka M, Soda H, et al. Gefitinib (“Iressa”, ZD1839), an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, reverses breast cancer resistance protein/ABCG2-mediated drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1541–1546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniel AR, Qiu M, Faivre EJ, et al. Linkage of progestin and epidermal growth factor signaling: Phosphorylation of progesterone receptors mediates transcriptional hypersensitivity and increased ligand-independent breast cancer cell growth. Steroids. 2007;72:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborne CK, Shou J, Massarweh S, et al. Crosstalk between estrogen receptor and growth factor receptor pathways as a cause for endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:865s–870s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui X, Schiff R, Arpino G, et al. Biology of progesterone receptor loss in breast cancer and its implications for endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7721–7735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunbier AK, Anderson H, Folkerd EJ, et al. Expression of estrogen responsive genes in breast cancers correlates with plasma estradiol levels in postmenopausal women. Presented at the 31st Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 13, 2008; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Su H, Rahimi M, et al. EGFRvIII-induced estrogen-independence, tamoxifen-resistance phenotype correlates with PgR expression and modulation of apoptotic molecules in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2021–2028. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arpino G, Weiss H, Lee AV, et al. Estrogen receptor-positive, progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer: Association with growth factor receptor expression and tamoxifen resistance. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1254–1261. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neven P, Pochet N, Drijkoningen M, et al. Progesterone receptor in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: The association between HER-2 and lymph node involvement is age related. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1334. author reply 2595–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viale G, Regan MM, Maiorano E, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of centrally reviewed expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in a randomized trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal early breast cancer: BIG 1–98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3846–3852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creighton CJ, Kent Osborne C, van de Vijver MJ, et al. Molecular profiles of progesterone receptor loss in human breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:287–299. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0017-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin K, DeVries S, Fridlyand J, et al. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loi S, Haibe-Kains B, Desmedt C, et al. Definition of clinically distinct molecular subtypes in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas through genomic grade. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1239–1246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu KD, Liu GY, Di GH, et al. Progesterone receptor status provides predictive value for adjuvant endocrine therapy in older estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients. Breast. 2007;16:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki R, Orsini N, Saji S, et al. Body weight and incidence of breast cancer defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status—a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:698–712. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson SC, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Glycemic load, glycemic index and breast cancer risk in a prospective cohort of Swedish women. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:153–157. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose-Hellekant TA, Skildum AJ, Zhdankin O, et al. Short-term prophylactic tamoxifen reduces the incidence of antiestrogen-resistant/estrogen receptor-positive/progesterone receptor-negative mammary tumors. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:496–502. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowsett M on behalf of the ATAC trialists group. Analysis of time to recurrence in the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial according to estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;82(suppl 1):S7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cristofanilli M, Valero V, Mangalik A, et al. Phase II, randomized trial to compare anastrozole combined with gefitinib or placebo in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1904–1914. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston SRD. Endocrine therapy combined with signal transduction inhibitors a means to overcome resistance. Presented at the 31st Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 11, 2008; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osborne K, Neven P, et al. Randomised phase II study of gefitinib or placebo in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer. Abstract presented at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 13–16, 2007; San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polychronis A, Sinnett HD, Hadjiminas D, et al. Preoperative gefitinib versus gefitinib and anastrozole in postmenopausal patients with oestrogen-receptor positive and epidermal-growth-factor-receptor-positive primary breast cancer: a double-blind placebo-controlled phase II randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:383–391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, et al. Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2630–2637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman B, Mackey JR, Clemens MR, et al. Trastuzumab plus anastrozole versus anastrozole alone for the treatment of postmenopausal women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: Results from the randomized phase III TAnDEM study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5529–5537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2345–2351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creighton CJ, Kent Osborne C, van de Vijver M, et al. Gene expression profiles of ER+/PR− breast cancer are associated with genomic instability and Akt/mTOR signaling, and predict poor patient outcome better than clinically assigned PR status. Presented at the 30th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 14, 2007; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elledge R. Hormone receptors in breast cancer: Measurement and clinical implications. [accessed February 3, 2011]. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/hormone-receptors-in-breast-cancer-measurement-and-clinical-implications?source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150.

- 28.Osborne CK, Schiff R, Arpino G, et al. Endocrine responsiveness: Under-standing how progesterone receptor can be used to select endocrine therapy. Breast. 2005;14:458–465. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elledge RM, Green S, Pugh R, et al. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PgR), by ligand-binding assay compared with ER, PgR and pS2, by immuno-histochemistry in predicting response to tamoxifen in metastatic breast cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group study. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Green AR, et al. Biologic and clinical characteristics of breast cancer with single hormone receptor positive phenotype. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4772–4778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bardou VJ, Arpino G, Elledge RM, et al. Progesterone receptor status significantly improves outcome prediction over estrogen receptor status alone for adjuvant endocrine therapy in two large breast cancer databases. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1973–1979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui X, Zhang P, Deng W, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I inhibits progesterone receptor expression in breast cancer cells via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway: Progesterone receptor as a potential indicator of growth factor activity in breast cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:575–588. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoadley K, Weigman V, Fan C, et al. EGFR associated expression profiles vary with breast tumor subtype. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]