The article describes patient navigator programs and summarizes the elements of the health care law that are relevant to these programs.

Keywords: Disparities in cancer care, Health care law, Patient navigator programs, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Abstract

Patients in vulnerable population groups suffer disproportionately from cancer. The elimination of cancer disparities is critically important for lessening the burden of cancer. Patient navigator programs have been shown to improve clinical outcomes. Among its provisions relevant to disparities in cancer care, The Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act authorizes continued funding of patient navigator programs. However, given the current economic and political environment, this funding is in jeopardy. This article describes patient navigator programs and summarizes the elements of the health care law that are relevant to these programs. It is vital that the entire oncology community remain committed to leading efforts toward the improvement of cancer care among our most vulnerable patients.

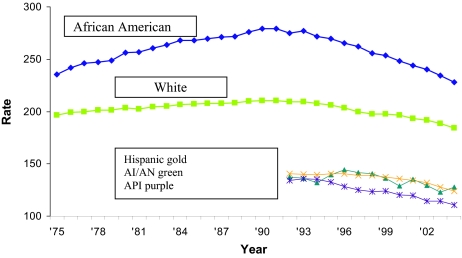

Despite a significant reduction in deaths resulting from cancer in the last decade, not all segments of the American population have experienced this improvement in cancer mortality (Fig. 1) [1]. Vulnerable population groups, such as racial and ethnic minorities and the uninsured, consistently experience poorer health as a consequence of substantial obstacles to receiving care, including lower access to state-of-the-art health care [1].

Figure 1.

Cancer mortality rates 1973–2004 by race. Incidence and mortality rates per 100,000 and age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2004.

Abbreviations: AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; API, Asian or Pacific Islander.

In March 2010, President Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) [2] as well as amendments to the PPACA under the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 [3]. This legislation contains provisions that provide opportunities and challenges for addressing disparities in cancer care [4]. Among the health reform law's many provisions relating to health disparities, it recognizes the important role of community-based organizations and health initiatives in preventing chronic disease and linking the public to health care services.

Specifically, the PPACA recognizes patient navigation as an important component for improving health care in vulnerable populations. The Public Health Service Act was amended to extend the Patient Navigator program. The PPACA adds a requirement to ensure that all patient navigators meet minimum core proficiencies. Organizations must verify navigator expertise in the type of intervention they will be performing. Three and a half million dollars is allotted for fiscal year 2010 and the program is authorized through fiscal year 2015 (section 3510) [2, 3].

Patient navigation was initially developed by Dr. Harold Freeman to address the burden of disease borne by residents of Harlem, NY [5]. His first program was composed of trained navigators who were members of the community or who were from the same cultural background as the population served. A program evaluation showed that patients who received patient navigator services received follow-up services significantly sooner than patients diagnosed prior to the program's initiation [6]. Over the years, patient navigation has continued to evolve and is generally recognized as an effective means to facilitate access to quality medical care by identifying and bridging gaps in understanding and encouraging compliance, thereby reducing barriers to care. Patient navigators are resources for patients and providers and assist with all phases of access, including primary cancer prevention, screening, postdiagnosis care, and survivorship care. Patient navigators can be social workers, trained community health workers, nurses, or trained volunteers.

Dr. Freeman's work and the efforts of others ultimately resulted in the passage of the Patient Navigator Act of 2005. This law authorized $25 million dollars in grants to create outreach programs with a focus on prevention, access to care, and screening in vulnerable communities. Stimulated by the Patient Navigator Act, the National Cancer Institute funded a nine-site Patient Navigation Research Program (PNRP) to design, implement, and evaluate patient navigation programs focusing on breast, colorectal, cervical, and prostate cancer throughout the U.S. Researchers within the PNRP are currently defining metrics to assess the process and outcomes of patient navigation in diverse settings, compared with control populations [7]. Another research objective of the PNRP is to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of patient navigation programs, taking into account factors such as the heterogeneity of navigation programs, the gap between establishing navigation programs and measuring outcomes of interest, and a host of other issues that may influence both access to services and outcomes [8]. The results of these and other studies will provide additional valuable data regarding the effectiveness of patient navigation programs.

Patient navigation programs have been increasingly adopted throughout the U.S. Numerous studies have suggested that these programs improve the quality of health care among patients served. One report by The Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute outlined significantly better diagnosis and 5-year survival rates among patients with breast cancer receiving patient navigation when their experience was compared with that of patients diagnosed prior to the initiation of the program [9–11]. The percentage of patients diagnosed at stage 3 and stage 4 dropped from 50% (in 1972–1986) to 21% (in 1995–2000), and the 5-year survival rate rose from 39% to 70% for two cohorts of patients with low socioeconomic status, of whom half had no medical insurance [9–11]. Another study showed that the length of time from patient referral to breast cancer treatment completion trended in favor of patients who were enrolled in patient navigation programs [12].

Additional evidence of the benefits of patient navigation programs includes a qualitative synthesis of 45 articles published through October 2007. Sixteen studies provided data on the efficacy of navigation in improving the timeliness and receipt of cancer screening, diagnostic follow-up care, and treatment. Patient navigation was found to increase participation in cancer screening and adherence to diagnostic follow-up care after the detection of an abnormality, because the absolute rate of screening was higher at about 17%, versus 11%, and the absolute rate of adherence to diagnostic follow-up care was 29%, versus 21%, when compared with control patients [13]. Obviously there is greater room for further improvement.

In Boston, the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Avon Breast Care Program provides patient navigation services to reduce disparities in breast cancer among disadvantaged minority communities in the surrounding areas. Supported by the Avon Foundation since 2001, this patient navigator program currently serves community health centers in Chelsea, Massachusetts, with a large Latina population, Mattapan and Dorchester, with Haitian, African-American, and Vietnamese populations, and Cape Cod, with a large Portuguese population. Through this program, a seamless referral and navigation system has brought >4,000 patients from these health centers to MGH and other major area medical centers for diagnosis and treatment. At the MGH, appointments for evaluation of abnormal findings on mammography are expedited, and usually completed within 2 weeks. The program has identified and facilitated the care of 179 breast cancer patients, has assured a high standard of compliance with screening and follow-up care, has solved logistical problems in keeping appointments and maintaining compliance, and has established a partnership between health centers and tertiary care hospitals. Our current rates of compliance for breast cancer mammography in the Chelsea community approach 85%. Since October 2007, the program has tracked the number of days between program referral for an abnormal finding and a kept appointment. For patients referred to the program between October 1, 2007 and June 30, 2010, 75% arrived to a first appointment in ≤30 days and nearly all (90%) arrived within 60 days, many of whom may not have followed up or received care otherwise. Programs such as the MGH Avon Breast Care Program have become important models for the initiation of new navigator-based programs nationally at a time when racial and ethnic health disparities are receiving increased attention in recent health care reform efforts in the U.S.

However, despite the evidence that patient navigator programs improve clinical outcomes among vulnerable populations, funding for these programs remains in jeopardy. There is no single source of funding for navigation programs within the U.S. Currently, organizations that provide financial assistance for patient navigation include the federal government, local offices of minority health, nonprofit organizations, private foundations, and pharmaceutical companies. The degree of funding for patient navigation can vary depending on the political and economic climate. Therefore, it is critically important for the oncology community to support and secure continued funding for these valuable programs.

With its many provisions addressing disparities in cancer care, national health care reform may meaningfully change clinical outcomes among the most vulnerable Americans diagnosed with cancer. However, despite the law's many relevant and well-meaning provisions, it has serious limitations. Given the current fiscal climate in the U.S., the sustainability of health care reform remains in question and the implementation and feasibility of its community-based programs are equally vulnerable to ongoing budget negotiations. The wording of the law is vague and open to different interpretations. For example, the word “authorize” appears innumerably throughout the law rather than the word “appropriate.” Congress can authorize that a sum of money be spent on an initiative over a defined period of time (as occurs multiple times throughout this legislation); however, this does not actually obligate Congress to spend this money. Every year, Congress determines how much should be spent for the following 12 months. These authorized provisions are considered, but may not be funded. In the context of constrained financing, funding of the patient navigator programs is anything but a guarantee.

The PPACA has the potential to expand access to care and improve cancer care among vulnerable groups. Specifically, the law authorizes continued funding for patient navigation programs. However, this law alone does not guarantee funding of this or other important programs related to cancer disparities. Instead, the PPACA creates a new foundation for continuing to build meaningful policy changes. Going forward, it is imperative that the entire oncology community has a clear vision for building upon this landmark legislation. With the passing of national health care reform, now is the time for the oncology community to seriously address and eliminate cancer disparities. Our success in reducing health care disparities will depend on the strength of our efforts, our commitment to this cause, and our demand for federally funded programs for ensuring access to care for the disadvantaged.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Beverly Moy, Bruce A. Chabner

Collection and/or assembly of data: Beverly Moy

Data analysis and interpretation: Beverly Moy

Manuscript writing: Beverly Moy, Bruce A. Chabner

Final approval of manuscript: Beverly Moy, Bruce A. Chabner

References

- 1.Mead H, Cartwright-Smith L, Jones K, et al. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2008. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in US Healthcare: A Chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Law 111–148. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2010 Mar 23; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Law 111–152. Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. 2010 Mar 23; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8903. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins J, Mumber MP. Patient navigation through the cancer care continuum: An overview. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:150–152. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0943501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vargas RB, Ryan GW, Jackson CA, et al. Characteristics of the original patient navigation programs to reduce disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:426–433. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113:3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsey S, Whitley E, Mears VW, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of cancer patient navigation programs: Conceptual and practical issues. Cancer. 2009;115:5394–5403. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler T, Steakley C, Garcia AR, et al. Reducing disparities in the burden of cancer: The role of patient navigators. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman HP. A model navigation program. Oncol Iss. 2004;5:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwaderer KA, Proctor JW, Martz EF, et al. Evaluation of patient navigation in a community radiation oncology center involved in disparities studies: A time-to-completion-of-treatment study. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:220–224. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0852001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113:1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]