This fourth part of a four-part series on pharmacogenetics focuses on pharmacodynamic variability and encompasses genetic variation in drug target genes such as those encoding thymidylate synthase, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, and ribonucleotide reductase. Potential implications and opportunities for patient and drug selection for genotype-driven anticancer therapy are outlined.

Keywords: Pharmacogenetics, Personalized medicine, Pharmacodynamics, Oncology, Anticancer drugs

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Identify genetic polymorphisms within pharmacodynamic candidate genes that are potential predictive markers for treatment outcome with anticancer drugs.

Describe treatment selection considerations in patients with cancer who have genetic polymorphisms that could influence pharmacodynamic aspects of anticancer therapy.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

Response to treatment with anticancer drugs is subject to wide interindividual variability. This variability is expressed not only as differences in severity and type of toxicity, but also as differences in effectiveness. Variability in the constitution of genes involved in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of anticancer drugs has been shown to possibly translate into differences in treatment outcome. The overall knowledge in the field of pharmacogenetics has tremendously increased over the last couple of years, and has thereby provided opportunities for patient-tailored anticancer therapy. In previous parts of this series, we described pharmacogenetic variability in anticancer phase I and phase II drug metabolism and drug transport. This fourth part of a four-part series of reviews is focused on pharmacodynamic variability and encompasses genetic variation in drug target genes such as those encoding thymidylate synthase, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, and ribonucleotide reductase. Furthermore, genetic variability in other pharmacodynamic candidate genes involved in response to anticancer drugs is discussed, including genes involved in DNA repair such as those encoding excision repair crosscomplementing group 1 and group 2, x-ray crosscomplementing group 1 and group 3, and breast cancer genes 1 and 2. Finally, somatic mutations in KRAS and the gene encoding epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and implications for EGFR-targeted drugs are discussed. Potential implications and opportunities for patient and drug selection for genotype-driven anticancer therapy are outlined.

Introduction to the Series

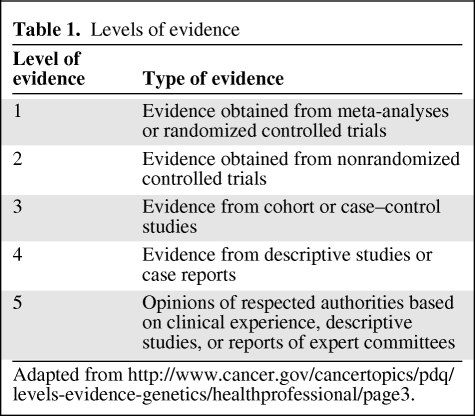

We present a series of four reviews about pharmacogenetic variability in anticancer phase I and phase II drug metabolism, drug transport, and pharmacodynamic drug effects. The previous three parts in this series focused on the molecular background and clinical implications of pharmacogenetic variability in candidate genes encoding proteins involved in the pharmacokinetics of anticancer drugs. This fourth part of the series deals with pharmacogenetic variability in genes involved in pharmacodynamic drug effects and other drug response mechanisms. Subsequently, opportunities for patient-tailored anticancer pharmacotherapy are provided based on current knowledge in the field of oncology. Herein, the level of evidence for each of the reviewed studies was taken into account according to the levels of evidence provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Levels of evidence

Introduction to Pharmacodynamic Variability

Complementary to the field of pharmacokinetics, which studies the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of drugs, the area of pharmacodynamics explores the effect of drugs on receptors and other response mechanisms. Interindividual differences in the expression and activity of proteins involved in drug disposition and drug effects, for example, induced by genetic polymorphism, may significantly affect response to (anticancer) drugs. Typical candidate genes involved in anticancer drug pathways that may contribute on a pharmacodynamic level to interpatient variability include those encoding thymidylate synthase (TYMS), methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), ribonucleotide reductase M1 (RRM1), excision repair crosscomplementing group 1 (ERCC1) and ERCC2, x-ray repair crosscomplementing group 1 (XRCC1) and XRCC3, breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) and BRCA2, KRAS, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Because polymorphism within these genes is capable of affecting anticancer pharmacotherapy, knowledge of the clinical impact of these polymorphisms may then enable personalized medicine by genotype-based drug and dose selection for the individual patient. Besides the above-mentioned genes, however, multiple additional pharmacodynamic candidate genes exist, such as BCR-ABL, KIT (CD117), PDGFR, BRAF, PIK3CA, etc., for information on which the reader is referred elsewhere [1–3].

TYMS

TYMS catalyzes the conversion of deoxyuridine monophosphate to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP), which is thereafter further phosphorylated to deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP). By providing the sole de novo intracellular source of dTMPs and thereby dTTPs, TYMS is essential in DNA synthesis and repair and cell proliferation. Anticancer drugs targeting TYMS include, among others, fluoropyrimidines and methotrexate. The main active metabolite of fluoropyrimidines, 5-fluoro-deoxyuridine-monophosphate, forms a ternary complex together with TYMS and methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2FH4). This leads to inhibition of TYMS and subsequent arrest of DNA synthesis followed by cell death [4–6].

5′Untranslated Region 28-bp Repeat in TYMS

The antitumor activity of 5-fluorouracil (FU) is inversely related to the expression level of TYMS; cells with a low expression level are more sensitive toward 5-FU than cells with a high expression level [7, 8]. A tandem repeat polymorphism in the 5′ promoter enhancer region of TYMS (TSER) is known to affect its level of expression. This allelic variant consists of a 28-bp sequence that is present with different numbers of repeats: 2, 3, 4, 5, and 9 (TSER*2, TSER*3, TSER*4, TSER*5, and TSER*9, respectively) repeats have been described; however, TSER*2 and TSER*3 are predominant [9–12]. The higher the number of repeats, the higher the expression level of TYMS [10]. Furthermore, within the second 28-bp repeat of TSER*3, a G>C single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) exists (TSER*3G/TSER*3C), which again reduces its expression. That is, TSER*3C has a lower expression level of TYMS than TSER*3G, which is comparable with the level of TSER*2 [13–17]. Based on these three alleles (TSER*2, TSER*3G, and TSER*3C), the expression level, and hence activity, of TYMS can be divided into three phenotypes: low activity (*2/*2 or *2/*3C or *3C/*3C), intermediate activity (*2/*3G or *3C/*3G), and high activity (*3G/*3G).

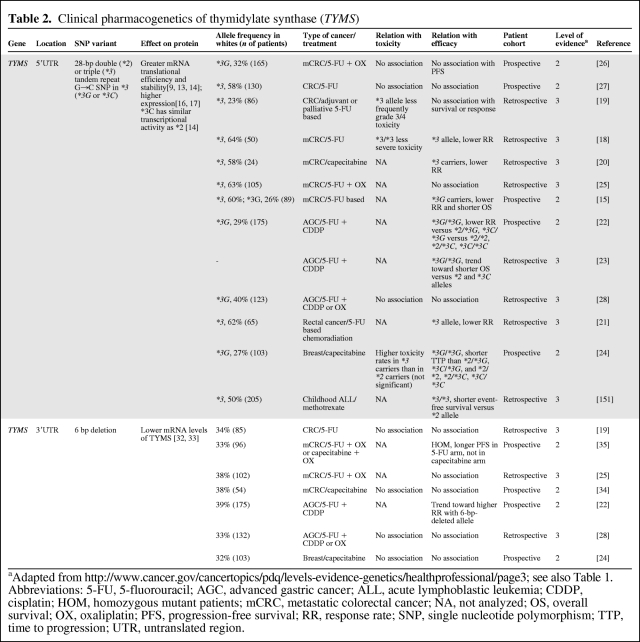

Multiple retro- and prospective pharmacogenetic studies have analyzed germline or normal tissue DNA to explore the effect of genetic polymorphism in TYMS on clinical outcome with fluoropyrimidines (Table 2). The majority of these studies showed lower clinical activity in patients with the high TYMS expression genotypes than in patients with low TYMS expression for patients with (metastatic) gastrointestinal or breast cancer treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. This is reflected by lower incidences of fluoropyrimidine-induced severe toxicity, and also a lower response rate or shorter progression-free or overall survival time [15, 18–24]. A few studies, though, showed no significant difference [25–28], or even an opposite association [29]. Possible explanations for this reported divergence in study outcomes, besides differences in study design, treatment regimen, patient selection, and population size, are additional genetic factors that might play a role. In particular, the G>C SNP within the second repeat of TSER*3, which is known to reduce TYMS expression, was not consistently assessed among the various studies. Nonetheless, based on these findings, it appears that the high TYMS expression genotype predicts for less clinical benefit from fluoropyrimidines than with low expression genotype. A meta-analysis would give further insight into the predictive value and clinical significance of this polymorphism. The hypothesis, however, is strengthened by the observations from two studies that analyzed tumor tissue DNA instead of germline DNA. One study of 221 patients with colorectal cancer, of whom 117 received 5-FU–based adjuvant chemotherapy and 104 patients did not, showed that *3/*3 patients had no long-term benefit from chemotherapy in terms of survival, whereas those with the *2/*2 or *2/*3 genotype had a significantly longer survival duration when given chemotherapy [30]. In addition, another study demonstrated that as a result of loss of heterozygosity at the TYMS locus in tumor cells, patients heterozygous for *2/*3 may either become *2/loss or *3/loss. Interestingly, patients with the tumor *2/loss genotype had a superior response to S-1 of 80%, versus 14% for those with the *3/loss genotype [31].

Table 2.

Clinical pharmacogenetics of thymidylate synthase (TYMS)

aAdapted from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/levels-evidence-genetics/healthprofessional/page3; see also Table 1.

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; AGC, advanced gastric cancer; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CDDP, cisplatin; HOM, homozygous mutant patients; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NA, not analyzed; OS, overall survival; OX, oxaliplatin; PFS, progression-free survival; RR, response rate; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TTP, time to progression; UTR, untranslated region.

To conclude, the 28-bp repeat polymorphism in TYMS affects its level of expression, and several studies provided evidence for an inverse relationship between the expression level of TYMS and the outcome of treatment with fluoropyrimidines. A few studies, though, reported no such association. A meta-analysis and additional prospective validation studies are warranted before patients with the TSER*2 or TSER*3C allele could possibly preferably be selected for anticancer therapy with fluoropyrimidines.

3′UTR 6-bp Deletion in TYMS

A deletion of six base pairs in its 3′UTR region is another common polymorphism in TYMS [32]. In vitro experiments in colorectal tumor tissue demonstrated lower mRNA stability and protein expression of TYMS with this 6-bp deletion [33]. Its clinical relevance, however, appears to be less pronounced than that of the 28-bp tandem repeat polymorphism, because the 3′UTR 6-bp deletion was shown not to be associated with toxicity or efficacy in patients with (metastatic) colorectal [19, 25, 34], gastric [28], or breast [24] cancer treated with 5-FU–based chemotherapy (Table 2). One study, though, in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer given oxaliplatin combined with either 5-FU or capecitabine, reported that the 6-bp del/del polymorphism was associated with a longer progression-free survival interval; however, this was seen only in patients treated with 5-FU and not in patients receiving capecitabine [35]. Given the fact however, that, by far, most studies did not report a significant association with clinical outcome from fluoropyrimidine therapy, it can be concluded that the 6-bp deletion in TYMS alone is not a clinically useful parameter for patient-tailored anticancer therapy. It is possible that in diplotype patients with the 28-bp repeat polymorphism, its positive predictive value could increase.

MTHFR

The enzyme MTHFR irreversibly reduces 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2FH4) to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-CH3FH4), which serves as a methyl-group provider for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and subsequent DNA methylation reactions. MTHFR enzyme activity and its related 5,10-CH2FH4 levels play a role in treatment with drugs that are involved in the folate pathway, including fluoropyrimidines and methotrexate. Theoretically, high levels of 5,10-CH2FH4, for example, as a result of low activity of MTHFR, result in greater inhibition of TYMS following treatment with fluoropyrimidines, which translates into superior efficacy of treatment. Indeed, in head and neck cancer patients receiving induction treatment with 5-FU–based chemotherapy, intratumoral levels of 5,10-CH2FH4 appeared to be significantly higher in complete responders than in partial responders or non-responders [36].

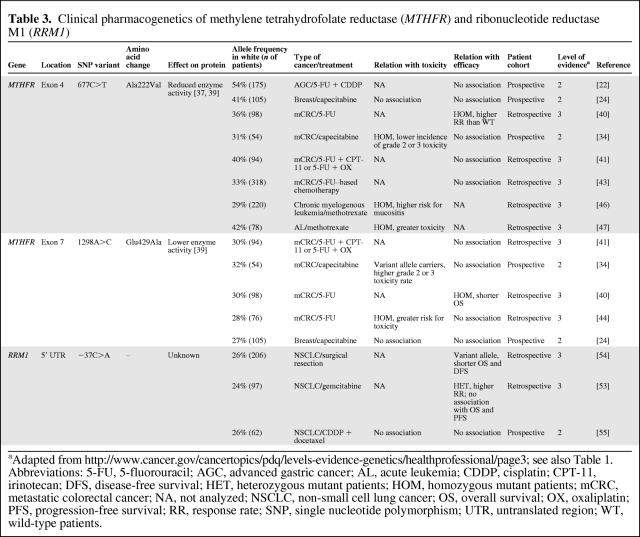

Two common nonsynonymous polymorphisms in MTHFR, 677C>T (Ala222Val) and 1298A>C (Glu429Ala), were shown to decrease MTHFR enzyme activity in vitro [37–39]. In line with the hypothesis, a retrospective study that analyzed tumor tissue DNA from 98 patients with colorectal cancer treated with fluorouracil demonstrated a higher response rate in patients with 677C>T homozygous mutated tumors than in patients with wild-type tumors [40]. Surprisingly, however, patients with 677C>T heterozygous tumors experienced the lowest response rate. This is rather striking because an intermediate response rate for this category would be expected, so the question evolves as to whether or not this observed effect really exists. Moreover, in studies analyzing germline DNA for 677C>T, the polymorphism was not associated with toxicity or survival with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in patients with (metastatic) colorectal cancer [27, 41–44], gastric cancer [22, 28], or breast cancer [24] (Table 3). In addition, a recent meta-analysis concluded that 677C>T was not predictive of response to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients [45].

Table 3.

Clinical pharmacogenetics of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and ribonucleotide reductase M1 (RRM1)

aAdapted from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/levels-evidence-genetics/healthprofessional/page3; see also Table 1.

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; AGC, advanced gastric cancer; AL, acute leukemia; CDDP, cisplatin; CPT-11, irinotecan; DFS, disease-free survival; HET, heterozygous mutant patients; HOM, homozygous mutant patients; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NA, not analyzed; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; OX, oxaliplatin; PFS, progression-free survival; RR, response rate; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; UTR, untranslated region; WT, wild-type patients.

This might, however, not necessarily be true for patients with leukemia treated with methotrexate, because two studies reported that homozygous 677C>T variant allele carriers experienced severe toxicity more frequently than wild-type patients [46, 47]. Additional prospective studies to confirm these findings are awaited.

In summary, the clinical significance of 677C>T appears to be low in treatment with fluoropyrimidines; however, it might be relevant for patients treated with methotrexate, for which further research is warranted.

With regard to MTHFR 1298A>C, two studies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with 5-FU [34] and capecitabine [44] reported that the variant allele was associated with a higher risk for toxicity; however, this was not observed in patients with breast cancer receiving capecitabine [24]. Furthermore, 1298A>C appears to have no effect on overall survival in cancer patients treated with fluoropyrimidines [24, 27, 34, 41, 44]. Further prospective studies are needed to determine whether 1298A>C truly affects the toxicity of fluoropyrimidines, without negatively influencing effectiveness on survival endpoints.

RRM1

RRM1 encodes the regulatory subunit of ribonucleotide reductase. This enzyme is involved in the production of deoxyribonucleotides that are essential for DNA synthesis. Additionally, RRM1 is a tumor suppressor gene, and overexpression of RRM1 has been shown to reduce cellular migration, invasion, and formation of metastases [48, 49]. Furthermore, RRM1 is a molecular target of the anticancer drug gemcitabine. One of the active metabolites of gemcitabine, gemcitabine diphosphate, inhibits the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase, thereby depleting the natural pool of deoxycytidine triphosphates for incorporation into DNA [50]. Therefore, although acting as a tumor suppressor gene, RRM1 overexpression is associated with lower efficacy for gemcitabine-based chemotherapy [51, 52]. Thus far, only a few studies have investigated the clinical effect of two polymorphisms (−37C>A and −524T>C) that are located in the promoter region of RRM1. Indeed, in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with gemcitabine, a higher response rate was observed for the reduced activity genotype; however, no association with survival was observed [53]. Furthermore, in patients with resected NSCLC not given gemcitabine, the highest predicted RRM1 activity by genotype was associated with a longer disease-free survival interval [54]. However, in cisplatin-docetaxel–treated patients with NSCLC, no effect on treatment outcome of these polymorphisms was reported [55]. Additional trials in non–gemcitabine-treated and gemcitabine-treated populations are needed to draw further conclusions on the clinical effect of polymorphism in RRM1.

DNA Damage and Repair

DNA is continuously exposed to DNA-damaging sources, such as reactive oxygen species, UV light, and other radiation sources, and chemicals including certain (anticancer) drugs. DNA damage is, among other things, expressed as single-strand breaks (SSBs) and double-strand breaks (DSBs), for which various coordinated pathways exist to repair the DNA strand breaks [56, 57]. These include the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway and the base excision repair (BER) pathway for SSBs and nonhomologous end-joining and homologous recombination (HR) for DSBs [58–61]. Besides many others, specific proteins that are involved in these DNA repair mechanisms are ERCC1 and ERCC2, XRCC1 and XRCC3, poly(ADP)-ribose polymerases (PARP), and the tumor-suppressor proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2.

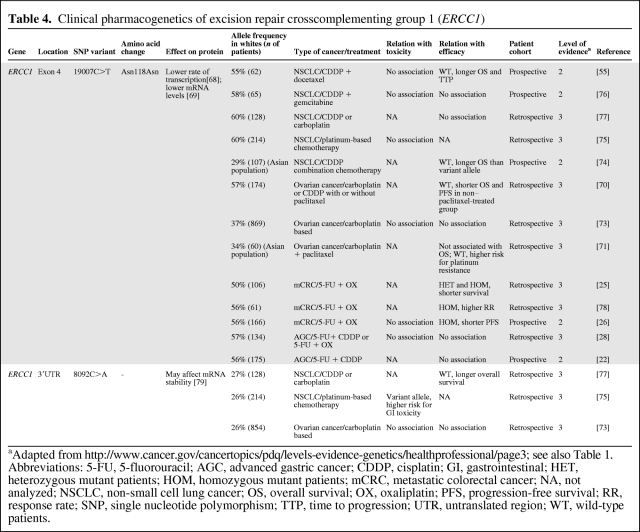

ERCC1

ERCC1 plays a role in the NER pathway and is involved in the repair of interstrand crosslinks in DNA and in recombination processes [62, 63]. Furthermore, it removes cisplatin-induced DNA adducts [64], and a high tumoral expression level of ERCC1 has been associated with resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy [65–67]. 19007C>T (Asn118Asn) is a synonymous SNP located in exon 4 of ERCC1, which reduces the transcription and mRNA levels of ERCC1, resulting in lower ERCC1 expression [68, 69]. Therefore, it is hypothesized that patients possessing the variant allele could favorably respond to platinum-based treatment regimens through a lower rate of removal of tumoral platinum-DNA adducts. The effect of 19007C>T has been evaluated in several clinical trials (Table 4). Indeed, in patients with ovarian cancer treated with platinum agents, two retrospective studies reported higher overall and progression-free survival rates for homozygous mutant patients [70] and a lower risk for platinum resistance for variant allele carriers [71]. Nonetheless, this could not be confirmed by others [72, 73]. Moreover, in patients with NSCLC who were treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, two studies reported that wild-type 19007C>T patients, that is, the ERCC1 high expression genotypes, experienced a longer survival duration than variant allele carriers [55, 74]. However, these associations are in contrast to the hypothesis, and were not observed in three other studies in patients with NSCLC [75–77].

Table 4.

Clinical pharmacogenetics of excision repair crosscomplementing group 1 (ERCC1)

aAdapted from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/levels-evidence-genetics/healthprofessional/page3; see also Table 1.

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; AGC, advanced gastric cancer; CDDP, cisplatin; GI, gastrointestinal; HET, heterozygous mutant patients; HOM, homozygous mutant patients; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NA, not analyzed; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; OX, oxaliplatin; PFS, progression-free survival; RR, response rate; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TTP, time to progression; UTR, untranslated region; WT, wild-type patients.

Also, in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with platinum-based chemotherapy, inconsistent findings with clinical outcome for 19007C>T were reported. Two studies showed a shorter (progression-free) survival duration for patients with the variant allele [25, 26], whereas others observed a greater response rate in homozygous mutant carriers [78]. Furthermore, in patients with advanced gastric cancer treated with platinum agents, 19007C>T was not associated with clinical outcome [22, 28].

In summary, multiple studies have addressed the question of whether or not ERCC1 19007C>T affects platinum-based treatment outcome. These trials show inconsistent findings, describing positive, negative, and no significant associations. This leads us to conclude that, to date, there is no particular evidence that 19007C>T in ERCC1 plays a significant role in anticancer treatment with platinum drugs. These inconsistent associations might be explained by differences in study design, population size, patient selection, stage of disease, treatment regimen, and ethnicity, but also (linkage to) additional genetic variants might play a role. However, because some significant associations were observed, the next question to address is why these were inconsistent over so many trials. For this, a meta-analysis would be of value.

8092C>A is another common polymorphism in ERCC1. It is located in the 3′UTR region and has been shown to affect ERCC1 mRNA stability [79]. In patients with NSCLC treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, a higher overall survival rate was reported for wild-type patients than for variant allele carriers [77]. However, in a larger study population of ovarian cancer patients receiving carboplatin plus either paclitaxel or docetaxel, no association with toxicity or survival was observed [73]. Further studies investigating the relationship between 8092C>A in ERCC1 and platinum-based treatment outcome are awaited.

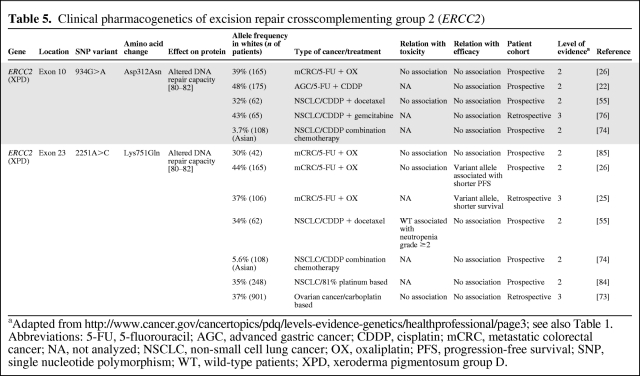

ERCC2

ERCC2, also known as xeroderma pigmentosum group D, encodes for a DNA helicase and is an essential enzyme in the NER pathway and, among other things, it is involved in the repair of platinum-DNA adducts. Two frequently occurring SNPs in ERCC2 are 934G>A (Asp312Asn) and 2251A>C (Lys751Gln). Despite inconsistent reports in the literature, it is assumed that these SNPs are associated with altered DNA repair capacity, and thereby potentially lead to differences in response to platinum agents among patients (Table 5) [80–82]. Nonetheless, for 934G>A, there were no associations with survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer [22], metastatic colorectal cancer [26], or NSCLC [55, 74, 76] treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, except for a retrospective study that showed that homozygous polymorphic patients with NSCLC experienced a shorter survival duration; however, this was seen only in patients with stage IIIA and stage IIIB disease, but not in those with stage IV disease [83].

Table 5.

Clinical pharmacogenetics of excision repair crosscomplementing group 2 (ERCC2)

aAdapted from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/levels-evidence-genetics/healthprofessional/page3; see also Table 1.

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; AGC, advanced gastric cancer; CDDP, cisplatin; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NA, not analyzed; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; OX, oxaliplatin; PFS, progression-free survival; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; WT, wild-type patients; XPD, xeroderma pigmentosum group D.

Also for ERCC2 2251A>C, no significant associations with survival in patients with NSCLC given platinum-based therapy were observed [55, 74, 76, 84]. Nonetheless, two studies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer showed that 2251A>C variant allele carriers experienced shorter progression-free and overall survival times than wild-type patients [25, 26], but this could not be confirmed by others [85].

To conclude, the clinical relevance of 934G>A in ERCC2 to platinum-based treatment appears thus far rather low, but for 2251A>C some evidence of a worse outcome with advanced metastatic colorectal cancer for variant allele carriers exist. Undoubtedly, additional trials are awaited.

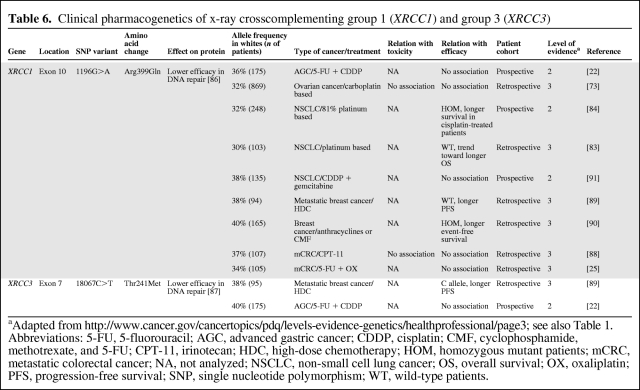

XRCC1 and XRCC3

Besides many other proteins involved in DNA repair, XRCC1 and XRCC3 are involved in the BER pathway. Two polymorphisms in XRCC1 and XRCC3—1196G>A (Arg399Gln) and 18067C>T (Thr241Met—have been shown to reduce DNA damage repair capacity [86, 87]. Therefore, these SNPs may contribute to interindividual variability in treatment response to DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics, including platinum agents, and also to ionizing radiation.

However, in chemotherapy-treated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [25, 88], ovarian cancer [73], and advanced gastric cancer [22], 1196G>A was not associated with survival (Table 6). Furthermore, two retrospective investigations in patients with (metastatic) breast cancer showed inconsistent results: one showed a longer progression-free survival interval for wild-type allele carriers, whereas the other study showed a longer event-free survival interval for homozygous mutant carriers [89, 90]. Similarly, in patients with NSCLC treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, one retrospective study showed a trend toward a longer overall survival time for patients with the wild-type allele [83], whereas a prospective study reported a longer overall survival time for homozygous mutant patients [84]. In addition, a second prospective study in NSCLC patients did not find an association with survival for 1196G>A in XRCC1 [91]. Overall, several studies reported inconsistent results on the clinical effect of XRCC1 1196G>A, which leads us to conclude that, at this moment, this SNP on its own is not a suitable predictor for treatment outcome with DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents.

Table 6.

Clinical pharmacogenetics of x-ray crosscomplementing group 1 (XRCC1) and group 3 (XRCC3)

aAdapted from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/levels-evidence-genetics/healthprofessional/page3; see also Table 1.

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; AGC, advanced gastric cancer; CDDP, cisplatin; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-FU; CPT-11, irinotecan; HDC, high-dose chemotherapy; HOM, homozygous mutant patients; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NA, not analyzed; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; OX, oxaliplatin; PFS, progression-free survival; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; WT, wild-type patients.

PARP and BRCA1- and BRCA2-Deficient Tumors

PARP is a family of multifunctional proteins, of which PARP-1 is the most important. PARP has an important assisting function in the repair of SSBs via the BER pathway [92, 93]. By inhibiting PARP, these DNA SSBs may accumulate and subsequently progress to DSBs when encountering a replication fork. These are normally repaired by the HR DSB repair pathway, in which BRCA1 and BRCA2 play essential roles [94]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 belong to the class of tumor suppressor genes and are key components in the HR repair pathway of DSBs [95]. Germline loss-of-function mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been associated with a high risk for developing malignancies such as breast and ovarian cancer [96]. Cells that carry heterozygous loss-of-function mutations may lose the wild-type allele (loss of heterozygosity), which subsequently lead to cells with a deficient HR system, driving carcinogenesis. This leads to a tumor-specific defect, in which tumor cells lack the DSB HR DNA repair capacity, whereas normal tissue cells have a proficient HR system. Subsequent PARP inhibition in HR-deficient tumor cells leads to accumulation of unrepaired SSBs that may progress to DSBs. These cannot be repaired and thereby result in a cytotoxic effect [97, 98]. Conversely, the HR repair system is proficient in normal cells, providing high tumor selectivity that can be exploited using specific PARP inhibitors such as olaparib [99]. Indeed, a recent phase I study showed substantial and durable antitumor activity in patients refractory to standard therapies when treated with single-agent olaparib [100]. Other phase I and phase II trials in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers are currently ongoing.

KRAS

KRAS is an intracellular protein and belongs to the superfamily of RAS proteins. KRAS is a GTP-binding protein and is a key regulator involved in the transduction of growth factor receptor–induced signals [101, 102]. Stimulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) by ligand binding (such as with growth factors) leads to activation of KRAS that then binds to GTP. This subsequently results in activation of further downstream pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphoinositide 3-kinase–Akt pathways, which are the main pathways by which cell cycle progression, desensitization of proapoptotic stimuli, angiogenesis, cellular proliferation, and growth are regulated [102, 103].

Cetuximab and panitumumab are anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies that inhibit signal transduction to KRAS by extracellular binding to EGFR. However, activating mutations in KRAS have been shown to lead to constitutively activated KRAS, independent of stimulation of EGFR, rendering EGFR inhibition by cetuximab or panitumumab ineffective in tumors harboring these activating mutations. Seven oncogenic mutations within exon 2 at codons 12 and 13 of KRAS (Gly12Asp, Gly12Ala, Gly12Val, Gly12Ser, Gly12Arg, Gly12Cys, and Gly13Asp) result in constitutively activated KRAS protein with subsequent promalignant downstream signal transduction, and are frequently present in various types of tumors [101, 104].

KRAS and Colorectal Cancer

Indeed, results from various trials in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving cetuximab or panitumumab have convincingly demonstrated that only patients with wild-type KRAS tumors at codons 12 and 13 are likely to respond to EGFR inhibitors in terms of a higher response rate and longer progression-free and overall survival times, whereas patients with mutated KRAS tumors do not respond at all, and have been shown to have a similar survival duration as patients not given anti-EGFR therapy [105–114]. This conclusive evidence prompted the European Medicines Agency followed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to update the label of cetuximab to advise against its use in colorectal cancer patients with codon 12 and 13 KRAS mutations. Panitumumab always had the wild-type KRAS label since its registration for colorectal cancer.

KRAS and Lung Cancer

Similar correlations have been observed for the small molecules erlotinib and gefitinib that target the tyrosine kinase (TK) domain of EGFR, but the evidence is thus far less convincing than that for treatment with anti-EGFR antibodies in colorectal cancer. In patients with lung cancer receiving one of the EGFR TK inhibitors (TKIs) erlotinib or gefitinib, activating mutations in KRAS are predictive of a lower response rate [115–119]. However, two studies reported that KRAS mutations were negative predictors of overall survival [115, 120], whereas three other trials showed no association [116, 117, 119]. Moreover, a phase III study in patients with NSCLC given the antibody cetuximab reported no correlation between efficacy parameters and KRAS mutation status. Although ample evidence has shown that mutated KRAS lung cancers do not likely respond to EGFR TKIs, more evidence is required to draw further conclusions on the survival benefit in wild-type and mutant KRAS patients given EGFR TKIs.

EGFR

EGFR is a TK transmembrane growth factor receptor and is an important regulator in the maintenance of normal cell function and proliferation. However, overexpression of EGFR is associated with development and progression of several types of malignancies [103]. EGFR overexpression may arise as a result of an increase in gene copy number and through acquirement of activating mutations in EGFR. The two main types of somatic gain-of-function mutations in EGFR are in-frame deletions in exon 19 around codons 746–750 and a missense substitution at codon 858 (Leu858Arg) in exon 21 [121–123]. These are nowadays termed the classical EGFR mutations and make up approximately 80%–90% of all genetic variants within the TK domain of EGFR. Furthermore, the presence of these mutations is highly associated with Asian ethnicity, never-smoking history, female gender, and adenocarcinoma histology, and they are most frequently observed in patients with NSCLC. Moreover, response to EGFR TKIs such as erlotinib and gefitinib is almost exclusively observed in patients harboring classical EGFR mutations—because of greater EGFR activity, the sensitivity toward EGFR TKIs is greater, which then often results in remarkable and durable responses [121–127]. Aside from NSCLC, these gain-of-function alterations are present but occur less frequently [128–130]. In unselected white NSCLC patients, the prevalence of somatic EGFR mutations is about 5%–15%, but it is 25%–35% in Asian patients [131]. Furthermore, because EGFR mutations and response to EGFR TKIs are more frequently present in Asian patients than in white patients, most studies evaluating EGFR mutations are performed in Asians. In addition, gefitinib was withheld from the U.S. market by the FDA in 2005 after failure to produce a longer overall survival duration than with best supportive care in non-Asian NSCLC patients as second- or third-line therapy [132]. Recently, it was approved in the European Union for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC tumors with activating mutations.

Over the last couple of years, numerous trials have demonstrated a significant positive correlation between response to EGFR TKIs and the presence of somatic EGFR mutations in patients with NSCLC [115–117, 119–121, 124, 126, 127, 131–143]. In addition, some studies have shown positive correlations with progression-free and overall survival times [115, 117, 119, 133–135, 139, 141–142]. Moreover, newly diagnosed white and Asian patients with NSCLC are currently screened for classical EGFR mutations to select patients for EGFR TKI treatment. This strategy achieves remarkably high response rates of about 75% (range, 55%–91%) and longer survival times using these targeted agents in a selected group of patients, compared with historical chemotherapy-treated controls [144–150]. Like wild-type KRAS in colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab, classical EGFR mutations in lung cancer patients targeted by EGFR TKIs is a key example of genotype-driven targeted therapy for the individual patient.

Conclusion: Implications for Clinical Practice and Opportunities for Patient-Tailored Anticancer Therapy

Pharmacodynamic proteins directly or indirectly interfere with the effect of drugs on receptors and other response mechanisms. Genetic polymorphism in genes involved in pharmacodynamic drug effects has been shown to, at least partially, explain the variability in treatment outcomes with anticancer drugs. This literature review shows that several genetic polymorphisms within pharmacodynamic candidate genes have evolved as predictive markers for treatment outcome with anticancer drugs.

For example, the TYMS high expression genotype TSER*3(G) appears to negatively affect treatment outcome with fluoropyrimidines. Because, currently, this polymorphism has been evaluated in multiple studies, a meta-analysis would be of further help to determine its predictive value.

A key example of patient-tailored anticancer therapy, however, is the use of PARP inhibitors in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cells carrying heterozygous BRCA1 or BRCA2 loss-of-function mutations may lose the wild-type allele; this drives carcinogenesis and results in a tumor-specific HR DNA repair defect. Subsequent inhibition of the BER pathway by PARP inhibition has shown substantial antitumor activity in patients refractory to standard chemotherapeutics.

A second classical example of genotype-driven anticancer therapy is the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting EGFR in colorectal cancer patients without codon 12 and 13 KRAS mutations. KRAS mutations lead to constitutively activated KRAS. Multiple studies have convincingly demonstrated (at least in colorectal cancer) that subsequent inhibition upstream of KRAS with monoclonal antibodies against EGFR is effective only in wild-type, but not in mutated, KRAS tumors.

Another example of individualized pharmacotherapy is the use of the small-molecule TKIs erlotinib and gefitinib in NSCLC patients harboring activating EGFR mutations. By selecting only activating EGFR mutation carriers for treatment with EGFR TKIs, response rates up to 91% have been achieved and survival is significantly longer than with standard chemotherapy regimens.

Overall, recent trials have provided several opportunities for genotype-based patient and drug selection that enables patient-tailored anticancer therapy. This is particularly true for the newer targeted agents, which have shown extremely high clinical benefits in subgroups of patients who can be selected using genetic approaches. These results highlight the opportunities for pharmacogenetics in oncology, and should encourage the continuation of pharmacogenetic research in the pharmacotherapeutic treatment of cancer.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Maarten J. Deenen, Annemieke Cats, Jos H. Beijnen, Jan H.M. Schellens

Collection and/or assembly of data: Maarten J. Deenen

Data analysis and interpretation: Maarten J. Deenen, Annemieke Cats, Jos H. Beijnen, Jan H.M. Schellens

Manuscript writing: Maarten J. Deenen, Annemieke Cats, Jos H. Beijnen, Jan H.M. Schellens

Final approval of manuscript: Maarten J. Deenen, Annemieke Cats, Jos H. Beijnen, Jan H.M. Schellens

References

- 1.Tefferi A. Molecular drug targets in myeloproliferative neoplasms: Mutant ABL1, JAK2, MPL, KIT, PDGFRA, PDGFRB and FGFR1. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:215–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jabbour E, Hochhaus A, Cortes J, et al. Choosing the best treatment strategy for chronic myeloid leukemia patients resistant to imatinib: Weighing the efficacy and safety of individual drugs with BCR-ABL mutations and patient history. Leukemia. 2010;24:6–12. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1308–1324. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grem JL. 5-Fluorouracil: Forty-plus and still ticking. A review of its preclinical and clinical development. Invest New Drugs. 2000;18:299–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1006416410198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rustum YM, Harstrick A, Cao S, et al. Thymidylate synthase inhibitors in cancer therapy: Direct and indirect inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:389–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welsh SJ, Titley J, Brunton L, et al. Comparison of thymidylate synthase (TS) protein up-regulation after exposure to TS inhibitors in normal and tumor cell lines and tissues. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2538–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leichman CG, Lenz HJ, Leichman L, et al. Quantitation of intratumoral thymidylate synthase expression predicts for disseminated colorectal cancer response and resistance to protracted-infusion fluorouracil and weekly leucovorin. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3223–3229. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.10.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishimura R, Nagao K, Miyayama H, et al. Thymidylate synthase levels as a therapeutic and prognostic predictor in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:5621–5626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horie N, Aiba H, Oguro K, et al. Functional analysis and DNA polymorphism of the tandemly repeated sequences in the 5′-terminal regulatory region of the human gene for thymidylate synthase. Cell Struct Funct. 1995;20:191–197. doi: 10.1247/csf.20.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneda S, Takeishi K, Ayusawa D, et al. Role in translation of a triple tandemly repeated sequence in the 5′-untranslated region of human thymidylate synthase mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1259–1270. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo HR, L ẌM, Yao YG, et al. Length polymorphism of thymidylate synthase regulatory region in Chinese populations and evolution of the novel alleles. Biochem Genet. 2002;40:41–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1014589105977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsh S, Ameyaw MM, Githang'a J, et al. Novel thymidylate synthase enhancer region alleles in African populations. Hum Mutat. 2000;16:528. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200012)16:6<528::AID-HUMU11>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakami K, Watanabe G. Identification and functional analysis of single nucleotide polymorphism in the tandem repeat sequence of thymidylate synthase gene. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6004–6007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Muller-Weeks S, et al. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism within the 5′ tandem repeat polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene abolishes USF-1 binding and alters transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2898–2904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcuello E, Altés A, del Rio E, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the 5′ tandem repeat sequences of thymidylate synthase gene predicts for response to fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:733–737. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami K, Omura K, Kanehira E, et al. Polymorphic tandem repeats in the thymidylate synthase gene is associated with its protein expression in human gastrointestinal cancers. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:3249–3252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morganti M, Ciantelli M, Giglioni B, et al. Relationships between promoter polymorphisms in the thymidylate synthase gene and mRNA levels in colorectal cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2176–2183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pullarkat ST, Stoehlmacher J, Ghaderi V, et al. Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism determines response and toxicity of 5-FU chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2001;1:65–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lecomte T, Ferraz JM, Zinzindohoué F, et al. Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism predicts toxicity in colorectal cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5880–5888. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park DJ, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, et al. Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism predicts response to capecitabine in advanced colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:46–49. doi: 10.1007/s003840100358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villafranca E, Okruzhnov Y, Dominguez MA, et al. Polymorphisms of the repeated sequences in the enhancer region of the thymidylate synthase gene promoter may predict downstaging after preoperative chemoradiation in rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1779–1786. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruzzo A, Graziano F, Kawakami K, et al. Pharmacogenetic profiling and clinical outcome of patients with advanced gastric cancer treated with palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1883–1891. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goekkurt E, Hoehn S, Wolschke C, et al. Polymorphisms of glutathione S-transferases (GST) and thymidylate synthase (TS)—novel predictors for response and survival in gastric cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:281–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Largillier R, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Formento JL, et al. Pharmacogenetics of capecitabine in advanced breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5496–5502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoehlmacher J, Park DJ, Zhang W, et al. A multivariate analysis of genomic polymorphisms: Prediction of clinical outcome to 5-FU/oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy in refractory colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:344–354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruzzo A, Graziano F, Loupakis F, et al. Pharmacogenetic profiling in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with first-line FOLFOX-4 chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1247–1254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gusella M, Frigo AC, Bolzonella C, et al. Predictors of survival and toxicity in patients on adjuvant therapy with 5-fluorouracil for colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1549–1557. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goekkurt E, Al-Batran SE, Hartmann JT, et al. Pharmacogenetic analyses of a phase III trial in metastatic gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma with fluorouracil and leucovorin plus either oxaliplatin or cisplatin: A study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2863–2873. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakobsen A, Nielsen JN, Gyldenkerne N, et al. Thymidylate synthase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism in normal tissue as predictors of fluorouracil sensitivity. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1365–1369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iacopetta B, Grieu F, Joseph D, et al. A polymorphism in the enhancer region of the thymidylate synthase promoter influences the survival of colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:827–830. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uchida K, Hayashi K, Kawakami K, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at the thymidylate synthase (TS) locus on chromosome 18 affects tumor response and survival in individuals heterozygous for a 28-bp polymorphism in the TS gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:433–439. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0200-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Velicer CM, et al. Searching expressed sequence tag databases: Discovery and confirmation of a common polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1381–1385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, et al. A 6 bp polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene causes message instability and is associated with decreased intratumoral TS mRNA levels. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:319–327. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma R, Hoskins JM, Rivory LP, et al. Thymidylate synthase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms and toxicity to capecitabine in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:817–825. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Balibrea E, Abad A, Aranda E, et al. Pharmacogenetic approach for capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil selection to be combined with oxaliplatin as first-line chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chéradame S, Etienne MC, Formento P, et al. Tumoral-reduced folates and clinical resistance to fluorouracil-based treatment in head and neck cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2604–2610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milos R, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: A common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet. 1995;10:111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Put NM, Gabreels F, Stevens EM, et al. A second common mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene: An additional risk factor for neural-tube defects? Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1044–1051. doi: 10.1086/301825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisberg I, Tran P, Christensen B, et al. A second genetic polymorphism in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) associated with decreased enzyme activity. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;64:169–172. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etienne MC, Formento JL, Chazal M, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms and response to fluorouracil-based treatment in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:785–792. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200412000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcuello E, Altés A, Menoyo A, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms: Genomic predictors of clinical response to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:835–840. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pare L, Salazar J, del Rio E, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms: Genomic predictors of clinical response to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy in females. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3468–3469. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W, Press OA, Haiman CA, et al. Association of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms and sex-specific survival in patients with metastatic colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3726–3731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capitain O, Boisdron-Celle M, Poirier AL, et al. The influence of fluorouracil outcome parameters on tolerance and efficacy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8:256–267. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zintzaras E, Ziogas DC, Kitsios GD, et al. MTHFR gene polymorphisms and response to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1285–1294. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ulrich CM, Yasui Y, Storb R, et al. Pharmacogenetics of methotrexate: Toxicity among marrow transplantation patients varies with the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism. Blood. 2001;98:231–234. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chiusolo P, Reddiconto G, Casorelli I, et al. Preponderance of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T homozygosity among leukemia patients intolerant to methotrexate. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1915–1918. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan H, Huang A, Villegas C, et al. The R1 component of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase has malignancy-suppressing activity as demonstrated by gene transfer experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13181–13186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bepler G, Gautam A, McIntyre LM, et al. Prognostic significance of molecular genetic aberrations on chromosome segment 11p15.5 in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1353–1360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heinemann V, Xu YZ, Chubb S, et al. Inhibition of ribonucleotide reduction in CCRF-CEM cells by 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bepler G, Kusmartseva I, Sharma S, et al. RRM1 modulated in vitro and in vivo efficacy of gemcitabine and platinum in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4731–4737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosell R, Danenberg KD, Alberola V, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase messenger RNA expression and survival in gemcitabine/cisplatin-treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1318–1325. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SO, Jeong JY, Kim MR, et al. Efficacy of gemcitabine in patients with non-small cell lung cancer according to promoter polymorphisms of the ribonucleotide reductase M1 gene. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3083–3088. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bepler G, Zheng Z, Gautam A, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase M1 gene promoter activity, polymorphisms, population frequencies, and clinical relevance. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Isla D, Sarries C, Rosell R, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and outcome in docetaxel-cisplatin-treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1194–1203. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jackson SP. Detecting, signalling and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:655–661. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedberg EC. DNA damage and repair. Nature. 2003;421:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nature01408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shuck SC, Short EA, Turchi JJ. Eukaryotic nucleotide excision repair: From understanding mechanisms to influencing biology. Cell Res. 2008;18:64–72. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takata M, Sasaki MS, Sonoda E, et al. Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double-strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintenance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:5497–5508. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Gent DC, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:196–206. doi: 10.1038/35056049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Silva IU, McHugh PJ, Clingen PH, et al. Defining the roles of nucleotide excision repair and recombination in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7980–7990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7980-7990.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sargent RG, Meservy JL, Perkins BD, et al. Role of the nucleotide excision repair gene ERCC1 in formation of recombination-dependent rearrangements in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3771–3778. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.19.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sancar A. Mechanisms of DNA excision repair. Science. 1994;266:1954–1956. doi: 10.1126/science.7801120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dabholkar M, Vionnet J, Bostick-Bruton F, et al. Messenger RNA levels of XPAC and ERCC1 in ovarian cancer tissue correlate with response to platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:703–708. doi: 10.1172/JCI117388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metzger R, Leichman CG, Danenberg KD, et al. ERCC1 mRNA levels complement thymidylate synthase mRNA levels in predicting response and survival for gastric cancer patients receiving combination cisplatin and fluorouracil chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:309–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:983–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu JJ, Mu C, Lee KB, et al. A nucleotide polymorphism in ERCC1 in human ovarian cancer cell lines and tumor tissues. Mutat Res. 1997;382:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5726(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu JJ, Lee KB, Mu C, et al. Comparison of two human ovarian carcinoma cell lines (A2780/CP70 and MCAS) that are equally resistant to platinum, but differ at codon 118 of the ERCC1 gene. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:555–560. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith S, Su D, Rigault de la Longrais IA, et al. ERCC1 genotype and phenotype in epithelial ovarian cancer identify patients likely to benefit from paclitaxel treatment in addition to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5172–5179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang S, Ju W, Kim JW, et al. Association between excision repair cross-complementation group 1 polymorphism and clinical outcome of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2006;38:320–324. doi: 10.1038/emm.2006.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krivak TC, Darcy KM, Tian C, et al. Relationship between ERCC1 polymorphisms, disease progression, and survival in the Gynecologic Oncology Group phase III trial of intraperitoneal versus intravenous cisplatin and paclitaxel for stage III epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3598–3606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marsh S, Paul J, King CR, et al. Pharmacogenetic assessment of toxicity and outcome after platinum plus taxane chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: The Scottish Randomised Trial in Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4528–4535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryu JS, Hong YC, Han HS, et al. Association between polymorphisms of ERCC1 and XPD and survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with cisplatin combination chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suk R, Gurubhagavatula S, Park S, et al. Polymorphisms in ERCC1 and grade 3 or 4 toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1534–1538. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tibaldi C, Giovannetti E, Vasile E, et al. Correlation of CDA, ERCC1, and XPD polymorphisms with response and survival in gemcitabine/cisplatin-treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1797–1803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou W, Gurubhagavatula S, Liu G, et al. Excision repair cross-complementation group 1 polymorphism predicts overall survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4939–4943. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Viguier J, Boige V, Miquel C, et al. ERCC1 codon 118 polymorphism is a predictive factor for the tumor response to oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6212–6217. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen P, Wiencke J, Aldape K, et al. Association of an ERCC1 polymorphism with adult-onset glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:843–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Au WW, Salama SA, Sierra-Torres CH. Functional characterization of polymorphisms in DNA repair genes using cytogenetic challenge assays. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1843–1850. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lunn RM, Helzlsouer KJ, Parshad R, et al. XPD polymorphisms: Effects on DNA repair proficiency. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:551–555. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spitz MR, Wu X, Wang Y, et al. Modulation of nucleotide excision repair capacity by XPD polymorphisms in lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1354–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gurubhagavatula S, Liu G, Park S, et al. XPD and XRCC1 genetic polymorphisms are prognostic factors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2594–2601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giachino DF, Ghio P, Regazzoni S, et al. Prospective assessment of XPD Lys751Gln and XRCC1 Arg399Gln single nucleotide polymorphisms in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2876–2881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Monzo M, Moreno I, Navarro A, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in nucleotide excision repair genes XPA, XPD, XPG and ERCC1 in advanced colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line oxaliplatin/fluoropyrimidine. Oncology. 2007;72:364–370. doi: 10.1159/000113534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lunn RM, Langlois RG, Hsieh LL, et al. XRCC1 polymorphisms: Effects on aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts and glycophorin A variant frequency. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2557–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Savas S, Ozcelik H. Phosphorylation states of cell cycle and DNA repair proteins can be altered by the nsSNPs. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hoskins JM, Marcuello E, Altes A, et al. Irinotecan pharmacogenetics: Influence of pharmacodynamic genes. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1788–1796. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bewick MA, Conlon MS, Lafrenie RM. Polymorphisms in XRCC1, XRCC3, and CCND1 and survival after treatment for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5645–5651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jaremko M, Justenhoven C, Schroth W, et al. Polymorphism of the DNA repair enzyme XRCC1 is associated with treatment prediction in anthracycline and cyclophosphamide/methotrexate/5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy of patients with primary invasive breast cancer. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:529–538. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32801233fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.de las Peñas R, Sanchez-Ronco M, Alberola V, et al. Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes modulate survival in cisplatin/gemcitabine-treated non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:668–675. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dantzer F, de La Rubia G, Ménissier-De Murcia J, et al. Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi0003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Amé JC, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. The PARP superfamily. Bioessays. 2004;26:882–893. doi: 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCabe N, Turner NC, Lord CJ, et al. Deficiency in the repair of DNA damage by homologous recombination and sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8109–8115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gudmundsdottir K, Ashworth A. The roles of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and associated proteins in the maintenance of genomic stability. Oncogene. 2006;25:5864–5874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wooster R, Weber BL. Breast and ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2339–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tutt AN, Lord CJ, McCabe N, et al. Exploiting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells in the design of new therapeutic strategies for cancer. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:139–148. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: The first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1626–1634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Benvenuti S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. Oncogenic activation of the RAS/RAF signaling pathway impairs the response of metastatic colorectal cancers to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapies. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2643–2648. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.De Roock W, Piessevaux H, De Schutter J, et al. KRAS wild-type state predicts survival and is associated to early radiological response in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:508–515. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Di Fiore F, Blanchard F, Charbonnier F, et al. Clinical relevance of KRAS mutation detection in metastatic colorectal cancer treated by cetuximab plus chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1166–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lièvre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3992–3995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lièvre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, et al. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:374–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yen LC, Yeh YS, Chen CW, et al. Detection of KRAS oncogene in peripheral blood as a predictor of the response to cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4508–4513. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Khambata-Ford S, Garrett CR, Meropol NJ, et al. Expression of epiregulin and amphiregulin and K-ras mutation status predict disease control in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3230–3237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X, et al. KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2890–2896. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Miller VA, Riely GJ, Zakowski MF, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, et al. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Hirsh V, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib and docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer: Data from the randomized phase III INTEREST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:744–752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhu CQ, Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4268–4275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, et al. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: Biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8919–8923. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, et al. EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: Analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:857–865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sordella R, Bell DW, Haber DA, et al. Gefitinib-sensitizing EGFR mutations in lung cancer activate anti-apoptotic pathways. Science. 2004;305:1163–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.1101637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Barber TD, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, et al. Somatic mutations of EGFR in colorectal cancers and glioblastomas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200412303512724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gwak GY, Yoon JH, Shin CM, et al. Detection of response-predicting mutations in the kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in cholangiocarcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:649–652. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lee JW, Soung YH, Kim SY, et al. Somatic mutations of EGFR gene in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2879–2882. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cortes-Funes H, Gomez C, Rosell R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor activating mutations in Spanish gefitinib-treated non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1081–1086. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Han SW, Kim TY, Hwang PG, et al. Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2493–2501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Huang SF, Liu HP, Li LH, et al. High frequency of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations with complex patterns in non-small cell lung cancers related to gefitinib responsiveness in Taiwan. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8195–8203. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kim KS, Jeong JY, Kim YC, et al. Predictors of the response to gefitinib in refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2244–2251. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rosell R, Ichinose Y, Taron M, et al. Mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the EGFR gene associated with gefitinib response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;50:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Taron M, Ichinose Y, Rosell R, et al. Activating mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with improved survival in gefitinib-treated chemorefractory lung adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5878–5885. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tokumo M, Toyooka S, Kiura K, et al. The relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and clinicopathologic features in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1167–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yang CH, Yu CJ, Shih JY, et al. Specific EGFR mutations predict treatment outcome of stage IIIB/IV patients with chemotherapy-naive non-small-cell lung cancer receiving first-line gefitinib monotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2745–2753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Takano T, Ohe Y, Sakamoto H, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and increased copy numbers predict gefitinib sensitivity in patients with recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6829–6837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhang XT, Li LY, Mu XL, et al. The EGFR mutation and its correlation with response of gefitinib in previously treated Chinese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1334–1342. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, et al. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:958–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Asahina H, Yamazaki K, Kinoshita I, et al. A phase II trial of gefitinib as first-line therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, et al. Prospective phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3340–3346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Tamura K, Okamoto I, Kashii T, et al. Multicentre prospective phase II trial of gefitinib for advanced non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: Results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group trial (WJTOG0403) Br J Cancer. 2008;98:907–914. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sequist LV, Martins RG, Spigel D, et al. First-line gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harboring somatic EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2442–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Yoshida K, Yatabe Y, Park JY, et al. Prospective validation for prediction of gefitinib sensitivity by epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Sunaga N, Tomizawa Y, Yanagitani N, et al. Phase II prospective study of the efficacy of gefitinib for the treatment of stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR mutations, irrespective of previous chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2007;56:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Krajinovic M, Costea I, Chiasson S. Polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene and outcome of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2002;359:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]