Sexual functioning and its relationship to cancer-related fatigue, mood disorder, and quality of life over the first year after completion of adjuvant therapy were examined in early-stage breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Fatigue, Sexual dysfunction, Quality of life

Learning Objectives

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Explain the relationship between cancer-related fatigue and sexual function.

Identify the presence of mood disorder as a key determinant of sexual problems after adjuvant breast cancer therapy.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com

Abstract

Background.

We recently reported that cancer-related fatigue (CRF) after adjuvant breast cancer therapy was prevalent and disabling, but largely self-limiting within 12 months. The current paper describes sexual functioning (SF) and its relationship to CRF, mood disorder, and quality of life (QOL) over the first year after completion of adjuvant therapy.

Methods.

Women were recruited after surgery, but prior to commencing adjuvant treatment, for early-stage breast cancer. Self-reported validated questionnaires assessed SF, CRF, mood, menopausal symptoms, disability, and QOL at baseline, completion of therapy, and at 6 months and 12 months after treatment.

Results.

Of the 218 participants, 92 (42%) completed the SF measure (mean age, 50 years). They were significantly younger, more likely to be partnered, and less likely to be postmenopausal than nonresponders. At baseline, 40% reported problems with sexual interest and 60% reported problems with physical sexual function. SF scores declined across all domains at the end of treatment, then improved but remained below baseline at 12 months, with a significant temporal effect in the physical SF subscale and a trend for overall satisfaction. There were significant correlations between the SF and QOL domains (physical and emotional health, social functioning, and general health) as well as overall QOL. The presence of mood disorder, but not fatigue, demographic, or treatment variables, independently predicted worse overall sexual satisfaction.

Conclusions.

Sexual dysfunction is common after breast cancer therapy and impacts QOL. Interventions should include identification and treatment of concomitant mood disorder.

Introduction

Advances in adjuvant therapy for breast cancer have resulted in improved survival, but at the cost of adverse effects on physical and psychosocial well-being. The effect of a breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment on sexual functioning remains poorly understood.

Our current knowledge of the prevalence and nature of sexual dysfunction in women with breast cancer is derived mainly from cross-sectional studies [1–6], which demonstrate that 30%–60% of women treated for breast cancer report sexual problems. Specific concerns include vaginal dryness (42%–56%) [1–3], dyspareunia (35%–52%) [1, 3–5], and low libido (48%–64%) [3, 4]. More recently, prospective assessments have revealed lower incidences of these concerns (vaginal dryness, 9%–18%, dyspareunia, 8%–17%, poor libido, 26%–45%) [1, 7–9]. Most report that younger or premenopausal women are more affected by sexual dysfunction than postmenopausal women [1, 3, 4, 10], but some have not found such a relationship [5, 11]. Chemotherapy has been shown to have a significant effect on sexual function [3, 4, 10–13], but the long-term effects are not well understood, with some finding sexual problems lasting years after chemotherapy [12], but others finding that the effect of chemotherapy on sexual function resolves within a few months [11]. With respect to hormonal therapy, tamoxifen alone has little or no impact [3, 10, 12, 14], but the aromatase inhibitors are known to be associated with vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and low libido [7, 14, 15]. The type of breast surgery has generally been found to have no effect [3, 4, 11, 13], whereas the effect of breast irradiation on sexual function is not widely reported, but a significant effect has been found by some [11]. Overall, it would seem that sexual dysfunction is a significant problem for a large number of women after breast cancer treatment across all age groups, and for some women, the symptoms become chronic [5, 9, 16].

The natural history of sexual dysfunction after breast cancer remains poorly documented. Two studies have attempted to address this problem. Burwell et al. [11] evaluated 209 women aged ≤50 years in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis and demonstrated deterioration in sexual interest and function after initial treatment, compared with retrospective reports of function prediagnosis. Panjari et al. [14] recruited >1,000 breast cancer survivors who were enrolled within 12 months of diagnosis and found that 70% of partnered women aged <65 years reported sexual problems. Only the initial assessment in that study has been reported to date. Both these studies conducted baseline assessments several months after diagnosis, and in many cases after treatment; hence, the early natural history of sexual problems after breast cancer remains poorly described.

To date, the focus in studies of sexual function after breast cancer has been on menopausal and gynecological symptoms. However, both fatigue and mood disturbances are common problems in this population [17–21], and their impacts on sexual function are largely unexplored. It is recognized that patients with breast cancer who report fatigue are more bothered by menopausal symptoms than women without fatigue [17, 18]. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) may therefore have a negative impact on sexual function, either in its own right or by exacerbating dysfunction resulting from other causes.

In this analysis of data from the Follow-up after Cancer (FolCan) study [22, 23], we therefore examined: the incidence of sexual problems after breast cancer in a real-world setting, the predictors of sexual problems over 12 months after adjuvant therapy, and the potential impact of sexual problems on quality of life (QOL).

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were a subset of the women enrolled in the FolCan prospective cohort, which explored the natural history and risk factors of CRF after treatment for early-stage breast cancer (submitted for publication [22, 23]). In the FolCan study, women aged ≥18 years with stage I or stage II breast cancer and no significant medical or psychiatric comorbidities were recruited between April 2002 and March 2004 from six metropolitan hospitals following surgery and prior to commencement of adjuvant therapy, and they were followed for a total of 5 years.

Participation in the sexual function aspect of this study was optional given the sensitive nature of the topic. Women were considered to be participants in this substudy if they completed the sexual function questionnaire at baseline and at least one follow-up time point at either 6 or 12 months post-treatment.

Procedure

The study was conducted following approval from the human research ethics committees of the participating hospitals. Questionnaires were completed at baseline (postsurgery and prior to adjuvant therapy); upon completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both; and then at 6 months and 12 months after treatment. At baseline, demographic and clinical details were recorded, including the type of surgery, tumor histology, tumor size and stage, lymph node involvement, hormone receptor status, and menopausal status. Postmenopausal status was defined as amenorrhea for ≥12 months at recruitment. Details of adjuvant treatment were also recorded.

Questionnaires and Measures

Sexual functioning was measured using the CAncer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) sexual subscale [24]. The CARES sexual subscale has two domains: sexual interest and sexual function, with severity scores in the range of 0–4; a higher score indicates greater severity of problems. Additionally, the CARES sexual subscale includes a single item assessing overall satisfaction with sexual relationship derived from the Schover and Jensen Sexual History Form, rated 0–5 [25]. The CARES questionnaire has excellent reliability and validity and has been extensively used in the breast cancer population [1, 10, 24, 26, 27].

The Somatic and Psychological Health Report (SPHERE) questionnaire was used to assess clinically significant fatigue states and mood disorders, as measured by its SOMA and PSYCH subscales, respectively. This 34-item instrument was derived from the General Health Questionnaire GHQ-30 [28], a widely used screening instrument for major depression, and the Schedule of Fatigue and Anergia (SOFA) questionnaire, which was developed for the identification of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome [29]. The SPHERE was developed to assess common somatic and psychiatric symptoms in the medical and psychiatric settings [30–35] and has been used for the identification of protracted fatigue states occurring in conjunction with and independent of a mood disorder after infectious illness [36] and following therapy for cancer [19, 20, 37, 38]. The psychometric properties of the instrument have been described [29], and its reliability and construct validity in the identification of persisting fatigue syndromes and mood disorders have been demonstrated [29, 39].

Functional QOL was measured using the Medical Outcomes Survey – Short Form (SF)-36, which assesses functional health and well-being across eight domains (physical function, role limitation due to physical health, role limitation due to emotional problems, vitality, mental health, social function, bodily pain, and general health) [40]. The SF-36 is a reliable and validated instrument that has been used widely in research related to both cancer and nonmalignant diseases [17, 41–43]. The vitality and mental health subscales were included only in the calculation of the SF-36 physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores, because these illness dimensions were better captured using the SPHERE [20]. Australian population norms for the SF-36 were used in calculating these summary scores [44]. In addition, a single item from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire QLQ-C30 regarding self-report of overall QOL was included [45]. This item correlates with the global QOL scale on this instrument and has been shown to have independent prognostic significance in advanced breast cancer patients [46].

Menopausal symptoms were measured using the Blatt-Kupperman menopausal index (BMI) [47–51]. Disability was assessed by questioning the “days out of usual role due to illness” from the Brief Disability Questionnaire [52].

Data Analyses

The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants and nonparticipants are summarized using descriptive statistics, and group differences were assessed with independent-sample t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables, with Yates continuity correction when appropriate. Temporal changes within patients were assessed using one-way repeated measures analysis of variance. To investigate relationships between CARES scores and potential predictors of sexual functioning, Spearman's ρ correlations were used for continuous variables and point-biserial correlations were used for categorical variables. Holm's procedure was used to correct correlation matrices for multiple comparisons at each time point. Multivariate linear regression models were created based on the results of unadjusted correlations.

Results

Participants

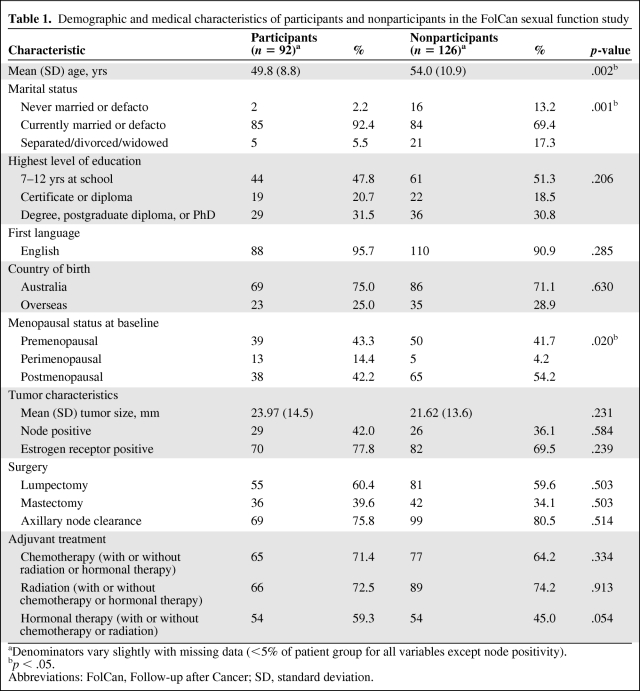

Of the 218 women who were recruited for the original study, 130 (60%) completed the CARES questionnaire at baseline, of whom follow-up data at 6 months, 12 months, or both were available for 92 (42% of the total cohort). The medical and demographic characteristics of these women are displayed in Table 1, as is a comparison with nonparticipants. Of note, participants were significantly younger, more likely to be married or in a de facto relationship, and less likely to be postmenopausal at baseline than nonrespondents.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics of participants and nonparticipants in the FolCan sexual function study

aDenominators vary slightly with missing data (<5% of patient group for all variables except node positivity).

bp < .05.

Abbreviations: FolCan, Follow-up after Cancer; SD, standard deviation.

Prevalence and Incidence of Sexual Problems

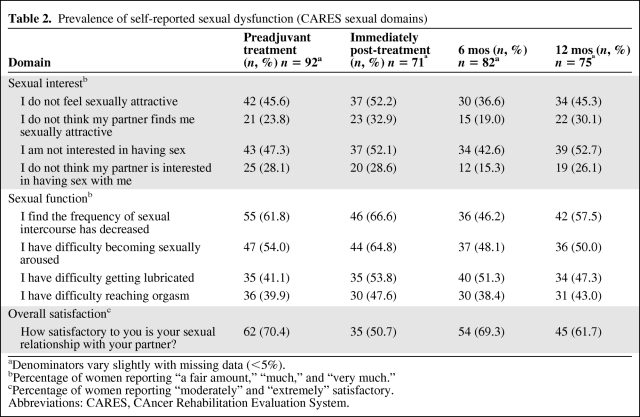

At baseline, 24%–47% of women answered “a fair amount” (n = 21) to “very much” (n = 42) to statements indicating issues with sexual interest, whereas 40%–60% of women reported a similar range of problems with sexual function (n = 35–55) (Table 2). Despite the relatively high prevalence of problems, 62 (70%) reported being “moderately” or “extremely” satisfied with their sex lives.

Table 2.

Prevalence of self-reported sexual dysfunction (CARES sexual domains)

aDenominators vary slightly with missing data (<5%).

bPercentage of women reporting “a fair amount,” “much,” and “very much.”

cPercentage of women reporting “moderately” and “extremely” satisfactory.

Abbreviations: CARES, CAncer Rehabilitation Evaluation System.

Immediately postchemotherapy or postradiotherapy, the proportion of women reporting sexual problems increased by 5%–10% for most domains. The most notable difference was evident in the functional subscale, with more women reporting difficulty with vaginal lubrication (which increased from 41% to 53%) and arousal (which increased from 54% to 65%). Overall, sexual satisfaction decreased over time.

After treatment, some improvements in each subscale were evident at the 6-month follow-up time point, followed by an apparent deterioration at 12 months, with failure to return to baseline levels in several domains. Fewer women were experiencing overall satisfaction at 12 months (n = 45, 62%) than at baseline (n = 62, 70%).

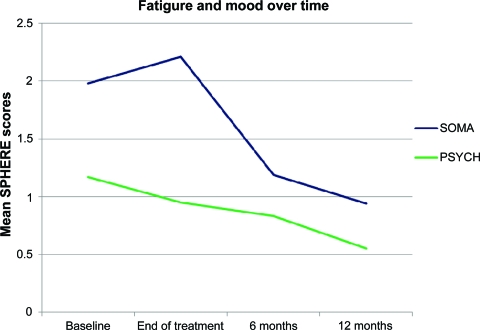

Temporal Changes in Sexual Functioning

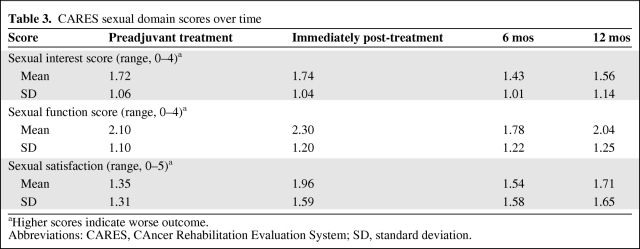

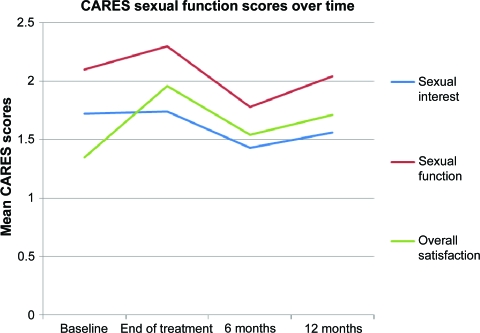

The mean CARES sexual function scores over time are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. A significant effect for time was found for the sexual function subscale (Wilks' λ = 0.827; p = .034), with a trend toward a significant effect for overall sexual satisfaction (λ = 0.869; p = .094). There was no effect for time on sexual interest (p = .50); however, this analysis may have been underpowered because of the relatively small number of patients with complete datasets (n = 48).

Table 3.

CARES sexual domain scores over time

aHigher scores indicate worse outcome.

Abbreviations: CARES, CAncer Rehabilitation Evaluation System; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

CAncer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) sexual domain scores over time. Higher scores indicate greater dysfunction.

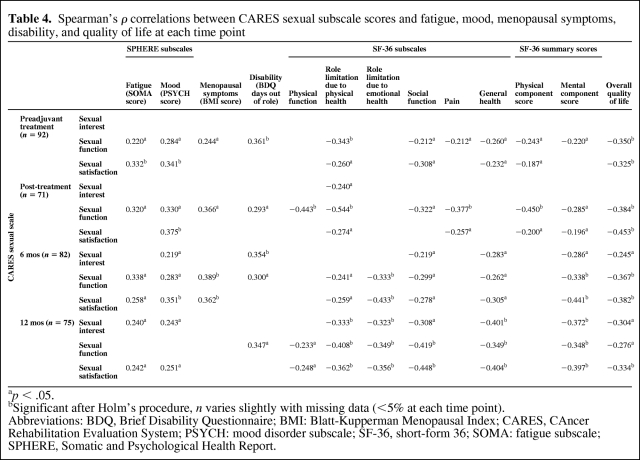

Fatigue and Mood Disorder

The trends in fatigue and mood disorder scores (SPHERE) over time are shown in Figure 2. As expected, there was a significant effect for time on fatigue scores (λ = 0.777; p = .005), with worse fatigue immediately after treatment, improving over time. There was also a significant effect for time on mood disturbance scores (λ = 0.829; p = .024), with high scores immediately after surgery and the end of treatment, but then improving over time.

Figure 2.

Trends in fatigue (SOMA) and mood (PSYCH) scores over time. Higher scores indicate more severe problems

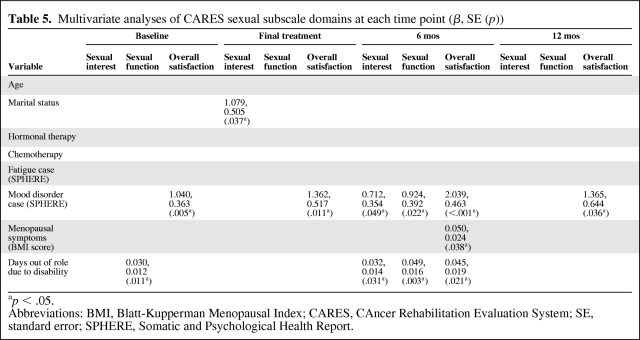

Exploring the Relationship Between Sexual Function and Fatigue

Correlations between the CARES sexual subscale and fatigue scores are shown in Table 4. There was a significant, but modest, positive correlation between worse fatigue and worse sexual function scores at baseline, the end of adjuvant treatment, and at 6 months, but not at 12 months. There was also a significant modest correlation between fatigue and poorer overall sexual satisfaction scores at all time points except for the end of treatment. Sexual interest and fatigue scores were correlated only at the 12-month time point.

Table 4.

Spearman's ρ correlations between CARES sexual subscale scores and fatigue, mood, menopausal symptoms, disability, and quality of life at each time point

ap < .05.

bSignificant after Holm's procedure, n varies slightly with missing data (<5% at each time point).

Abbreviations: BDQ, Brief Disability Questionnaire; BMI: Blatt-Kupperman Menopausal Index; CARES, CAncer Rehabilitation Evaluation System; PSYCH: mood disorder subscale; SF-36, short-form 36; SOMA: fatigue subscale; SPHERE, Somatic and Psychological Health Report.

Other Potential Associations with Sexual Function

There were significant positive correlations among mood disturbance scores, sexual function, and overall sexual satisfaction scores at all time points from baseline to 6 months, and for sexual satisfaction at 12 months (Table 4). Sexual interest and mood disturbance scores were correlated at 6 months and at 12 months.

For this group of women, no significant association was found between sexual subscale scores and the level of education or menopausal status, either at the time of breast cancer diagnosis or after treatment. Women who were married or in a de facto relationship were more likely to report problems with sexual interest at the end of treatment than unpartnered women (r = 0.292; p = .014), but no such relationship was seen at other time points. Younger women were more likely to report poorer overall satisfaction at the end of treatment (r = −0.266; p = .027), but not at other time points. Age did not correlate with other CARES domains.

With regard to the type of treatment received, chemotherapy was associated with poorer sexual function scores at the end of treatment (r = −0.256; p = .035), but not at other time points. Hormonal therapy was associated with poorer sexual function scores at 6 months (r = −0.286; p = .012) and sexual interest at 12 months (r = −0.232; p = .047). There was no relationship between receipt of radiotherapy or type of breast or axillary surgery and CARES sexual subscale scores. None of the demographic or treatment variables remained significantly correlated with sexual function after correction for multiple comparisons.

Menopausal symptom scores demonstrated a significant effect for time within patients, with mean scores of 13.0 at baseline, 14.5 at the end of treatment, 12.4 at 6 months, and 11.3 at 12 months (λ = 0.688; p < .001). Significant positive correlations were observed between CARES sexual function scores and menopausal symptoms at baseline, the end of treatment, and 6 months (Table 4). A relationship between overall sexual satisfaction and menopausal symptoms was seen only at 6 months. There was no relationship between menopausal scores and sexual interest. By 12 months, there were no correlations between menopausal symptom scores and any of the CARES subscales.

Surgery and adjuvant treatment were associated with significant disability, with women reporting a mean of 11 days out of role in the past month at baseline (standard deviation [SD], 10.6), 6 days at the end of treatment (SD, 9.3), 2.4 days at 6 months (SD, 6.1), and 1.4 days at 12 months (SD, 0.15) (significant for time; λ = 0.530; p < .001). There was a positive correlation between disability (i.e., days out of role) and sexual function at all time points (Table 4). There were no correlations between days out of role and overall sexual satisfaction.

Predictors of Sexual Problems

Based on the correlations above, linear regression models were created to identify predictors of CARES sexual subscale scores at each time point with age, marital status, and receipt of chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and radiotherapy together with fatigue and mood disturbance scores, menopausal symptoms, and days out of role as independent variables (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analyses of CARES sexual subscale domains at each time point (β, SE (p))

ap < .05.

Abbreviations: BMI, Blatt-Kupperman Menopausal Index; CARES, CAncer Rehabilitation Evaluation System; SE, standard error; SPHERE, Somatic and Psychological Health Report.

Overall, mood disorder and days out of role were the strongest independent predictors of sexual problems, with relationships seen at multiple time points. Notably, the presence of mood disorder was independently associated with the overall sexual satisfaction item at all time points.

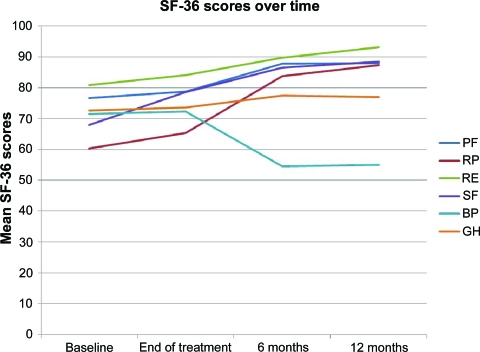

Exploring the Relationship Between Sexual Function and QOL

SF-36 scores showed steady improvements across a number of domains from baseline to 12 months (Fig. 3). Significant improvements from baseline to 12 months were seen in physical function (λ = 0.671; p < .001), role limitation due to physical health (λ = 0.414; p < .001), role limitation due to emotional health (λ = 0.768; p = .005), and social functioning (λ = 0.577; p < .001). A significant deterioration from baseline through all time points to 12 months was seen for pain scores (λ = 0.598; p < .001). No significant effect for time was found in the general health domain. With regard to the SF-36 summary scores, there was a significant improvement in the MCS over time (λ = 0.624; p < .001) but no significant effect for time in the PCS (λ = 0.926; p = .092).

Figure 3.

Trends in SF-36 quality of life domains over time. Higher scores indicate better function.

Abbreviations: BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; PF, physical function; RE, role limitation due to emotional problems; RP, role limitation due to physical health; SF, social functioning; SF-36, short-form 36.

The SF-36 QOL domains that were most strongly correlated with CARES scores were the role limitation due to physical health, role limitation due to emotional health, social functioning, and general health domains (Table 4). A significant correlation was seen at all time points for the sexual function domain. Significant correlations between SF-36 scores in these domains and the overall sexual satisfaction item were also seen at 6 months and at 12 months. Correlations between both the PCS and MCS and sexual function and satisfaction were seen at baseline and at final treatment, but by the 6- and 12-month time points, correlations were seen only between the MCS and the CARES sexual subscales.

There were significant correlations between the overall QOL item and CARES subscales at all time points, with the exception of sexual interest at baseline and final treatment. Multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to assess end-of-treatment variables that would predict QOL at 6 months and at 12 months. The model included age, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, radiation, fatigue and mood disturbance scores, disability, menopausal symptoms, and the three CARES sexual domains. At 6 months, the independent predictors of QOL were: receipt of hormonal therapy (p = .010), mood disturbance scores at the end of treatment (p = .030), and overall sexual satisfaction at the end of treatment (p = .032). By 12 months, the only independent predictors of QOL in this model were receipt of hormonal therapy (p = .021) and chemotherapy (p = .041).

Discussion

In this prospective study of women undergoing therapy for early breast cancer, approximately half of the women reported problems with sexual interest and function following surgery and prior to commencing adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Modest but significant increases in the incidences of these sexual problems were evident following the completion of adjuvant therapy, with sexual function more significantly affected than sexual interest. By 12 months, many women reported ongoing sexual problems, particularly with regard to vaginal lubrication, and fewer women described high levels of overall sexual satisfaction than at baseline. Because >80% of breast cancer survivors never have a discussion regarding sexual issues with their clinicians [53], the changes in sexual functioning found in this study should alert oncology teams to the need for raising, addressing, and counseling patients about anticipated changes in sexual function. The findings also highlight the importance of addressing mood disorder after cancer treatment, because it is the strongest independent predictor of sexual problems in these women.

It is important to emphasize that we cannot assume that sexual satisfaction is equal to the sum of sexual interest and sexual functioning. Our results indicate that it is possible to experience satisfaction despite high scores on the CARES subscales.

The overall trend in sexual function over the first 12 months after breast cancer therapy in our cohort was for a deterioration after adjuvant therapy, followed by an improvement at 6 months (in some areas to better than baseline levels), and then a further deterioration at 12 months. The apparent improvement in sexual function at 6 months post-treatment could be seen as counterintuitive and is difficult to explain. One could postulate that, by this time, women and their partners have adjusted to the physical and psychological changes associated with a cancer diagnosis and treatment and have adopted corresponding changes in their sexual relationships, but by 12 months, women and/or their partners may no longer find such changes satisfactory. Alternatively, these trends may reflect changes in relationship quality, which are known to mitigate changes in sexual satisfaction [10]. These theories deserve further exploration using qualitative methods.

Although it seems intuitive to assume that fatigue plays an important negative role in sexual functioning, this has not previously been investigated in the cancer setting. In the current study, both fatigue and sexual functioning worsened after adjuvant therapy, with improvements toward baseline levels by the end of the 12-month study period. Although significant correlations between sexual functioning and fatigue were noted at the end of treatment and at 6 months and 12 months post-treatment, the multivariate analysis indicated that fatigue was not a significant independent predictor of sexual problems. We previously reported that women with fatigue states commonly experience concomitant mood disorder [19, 20], and thus the relationship between fatigue and sexual function may be restricted to the subset with mood disorder.

Our finding that the presence of mood disorder was a strong independent predictor of overall sexual satisfaction in this study is consistent with previous studies [10, 54]. It suggests that interventions targeting sexual problems in cancer survivors need to address psychological well-being as well as physical and gynecological symptoms. Two randomized trials of more holistic approaches have shown promising results: a nurse-delivered comprehensive menopausal assessment with educational, counseling, and treatment components led to significant improvements in sexual function [55], and a group psychoeducational intervention showed positive effects on relationship adjustment and communication as well as greater satisfaction with sexual life than in controls [56]. In the latter study, the uptake of the intervention was suboptimal, however, with only 29% of eligible women participating.

Our finding of links among sexual function, sexual satisfaction scores, and QOL, has been reported by others in young breast cancer patients [1]. In particular, the women's report of dissatisfaction with their sex life at the end of treatment was an independent predictor of their QOL 6 months post-treatment. Whereas these data are insufficient to establish a causal relationship, the finding supports the assertion that sexual function matters in a woman's overall sense of well-being.

Unlike previous studies, we did not find any relationship between sexual functioning and age [4, 13, 54], treatment [4, 10, 12, 13, 53, 54], or menopausal status [4]. These differences may reflect the difference between our “real-world” cohort and the clinical trial populations of some of these studies, or a lack of sensitivity of the CARES instrument used in the present study. That hormonal therapy was not a major determinant of sexual function in our cohort may also reflect the recruitment period of the FolCan study, which was prior to the widespread availability of aromatase inhibitors in Australia, and as such, the women in this cohort received tamoxifen in the first 12 months after their breast cancer diagnosis. It is therefore possible that our findings may be different in a population treated with aromatase inhibitors. It should also be noted that, in the current study, menopausal symptoms were assessed using the BMI, which gives weight to vasomotor symptoms of menopause over other symptoms and does not include gynecological concerns such as vaginal dryness [48].

This study adds to the growing body of evidence that sexual dysfunction is a problem for a significant number of women after treatment for early breast cancer, and importantly, documents prospective changes in sexual function from the time of cancer surgery. Previous studies have been predominantly cross-sectional in nature [1–6], and those that have reported on temporal changes have relied mainly on retrospective recall rather than prospective data [2, 3, 5]. The prospective studies available to date have a baseline assessment several months after diagnosis and frequently after treatment [12, 14, 15].

Because participation in this sexual function substudy was optional, our cohort cannot be considered representative of the studied population. However, the fact that the participants were younger, more likely to be partnered, and less likely to be postmenopausal may indicate that those most likely to be troubled by treatment-related sexual dysfunction agreed to participate. The optional nature of participation in this study was, however, associated with limitations in sample size, which limited our ability to perform more complex statistical analyses, such as multivariate analyses of determinants of sexual function across time points. The quality of the partnered relationship was not explored in this study, and this can have a major influence on sexual function and satisfaction [3, 10, 54]. Future studies will benefit from including newer sexual function measures, such as the Sexual Activity Questionnaire [57], the Sexual function-Vaginal changes Questionnaire [58], and the Female Sexual Function Index [59], which incorporate assessment of relationship quality.

We also acknowledge that the baseline assessment in our cohort does not represent “prediagnosis” levels of sexual dysfunction, although our postsurgery assessment is closer to a true baseline than those used in other reports [12, 14, 15]. Retrospective self-reports in other studies suggest that up to one third of breast cancer patients experience some degree of sexual dysfunction prior to diagnosis [2]. A comparison of rates of baseline sexual dysfunction reported by breast cancer survivors and age-matched healthy women is also lacking, although other studies suggest comparable rates of dysfunction [3, 60]. Longer term follow-up would also be of interest to prospectively assess the long-term impact of a breast cancer diagnosis on sexual function.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that women with early-stage breast cancer commonly experience worsening of sexual function after initial adjuvant therapy. Although sexual function gradually improved, it did not return to postsurgery levels by 12 months. The presence of mood disorder, but not fatigue, demographic, or treatment variables, independently predicted poorer overall sexual satisfaction. Although fatigue also worsened after treatment, this problem did not predict sexual interest or satisfaction, suggesting that women recovering after breast cancer may be somewhat too tired to have as much sex, and may well be lacking in motivation because of a lowered mood, but will enjoy it when it happens.

Acknowledgments

The generous support of the women who gave their time to participate in the study is gratefully acknowledged.

The authors also acknowledge their co-investigators from the FolCan study group (F. Boyle, P. DeSouza, N. Wilcken, E. Scott, R. Toppler, P. Murie, L. O'Malley, J. McCourt, and I. Hickie), and the support shown to the study by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation (USA), the University of New South Wales, the Prince of Wales Hospital Department of Medical Oncology, Ramaciotti, Friends of the Mater, K. Willis, and S. Rovelli. We also thank Dusan Hadzi-Pavlovic for biostatistical support.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Barbara Bennett, David Goldstein, Michael Friedlander, Andrew R. Lloyd

Provision of study material or patients: David Goldstein, Michael Friedlander, Andrew R. Lloyd

Collection and/or assembly of data: Kate Webber, Barbara Bennett, Kelly Mok, Andrew R. Lloyd

Data analysis and interpretation: Kate Webber, Barbara Bennett, Kelly Mok, David Goldstein, Michael Friedlander, Andrew R. Lloyd, Ilona Juraskova

Manuscript writing: Kate Webber, Barbara Bennett, Kelly Mok, David Goldstein, Michael Friedlander, Andrew R. Lloyd

Final approval of manuscript: Kate Webber, Barbara Bennett, Kelly Mok, David Goldstein, Michael Friedlander, Andrew R. Lloyd, Ilona Juraskova

References

- 1.Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3322–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barni S, Mondin R. Sexual dysfunction in treated breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:149–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1008298615272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, et al. Sexuality following breast cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 1999;25:237–250. doi: 10.1080/00926239908403998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: Understanding women's health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindley C, Vasa S, Sawyer WT, et al. Quality of life and preferences for treatment following systemic adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1380–1387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortimer JE, Boucher L, Baty J, et al. Effect of tamoxifen on sexual functioning in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1488–1492. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cella D, Fallowfield L, Barker P, et al. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the ATAC (“Arimidex”, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years' adjuvant treatment for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallowfield LJ, Bliss JM, Porter LS, et al. Quality of life in the Intergroup Exemestane Study: A randomized trial of exemestane versus continued tamoxifen after 2 to 3 years of tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:910–917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinovszky KM, Gould A, Foster E, et al. Quality of life and sexual function after high-dose or conventional chemotherapy for high-risk breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1626–1631. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, et al. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2371–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaeline C, et al. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2815–2821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, et al. Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: A prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2788–2796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: First results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:376–387. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panjari M, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Sexual function after breast cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8:294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mok K, Juraskova I, Friedlander M. The impact of aromatase inhibitors on sexual functioning: Current knowledge and future research directions. Breast. 2008;17:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaus A, Boehme C, Thr̈limann B, et al. Fatigue and menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer undergoing hormonal cancer treatment. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:801–806. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein D, Bennett B, Friedlander M, et al. Fatigue states after cancer treatment occur both in association with, and independent of, mood disorder: A longitudinal study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:240. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett B, Goldstein D, Lloyd A, et al. Fatigue and psychological distress—exploring the relationship in women treated for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1689–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander S, Minton O, Andrews P, et al. A comparison of the characteristics of disease-free breast cancer survivors with or without cancer-related fatigue syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein D, Bennett BK, Cameron B, et al. A prospective cohort study of fatigue after adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: Association with hematologic, endocrine, and immune parameters. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):9596. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webber K, Goldstein D, Bennett BK, et al. Late fatigue after adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is largely unrelated to cancer or its treatment: 5 year follow up of a prospective cohort study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6(suppl 2):59–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganz PA, Schag CA, Lee JJ, et al. The CARES: A generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1992;1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00435432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schover LR, Jensen SB. New York: Guilford Press; 1988. Sexuality and Chronic Illness: A Comprehensive Approach; pp. 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schag CA, Heinrich RL, Aadland RL, et al. Assessing problems of cancer patients: Psychometric properties of the cancer inventory of problem situations. Health Psychol. 1990;9:83–102. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganz PA, Schag CA, Cheng HL. Assessing the quality of life—a study in newly-diagnosed breast cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:75–86. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg D, Williams P. Windsor, U.K.: NFER-Nelson Publishing Company; 1998. A Users Guide to the General Health Questionnaire; pp. 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Hickie IB, Wilson AJ, et al. Screening for prolonged fatigue syndromes: Validation of the SOFA scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s001270050266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hickie I, Koschera A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. The temporal stability and co-morbidity of prolonged fatigue: A longitudinal study in primary care. Psychol Med. 1999;29:855–861. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hickie I, Davenport T, Vernon SD, et al. Are chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome valid clinical entities across countries and health-care settings? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:25–35. doi: 10.1080/00048670802534432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Development of a simple screening tool for common mental disorders in general practice. Med J Aust. 2001;175(suppl):S10–S17. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Naismith SL, et al. SPHERE: A national depression project. SPHERE National Secretariat. Med J Aust. 2001;175(suppl):S4–S5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Naismith SL, et al. Conclusions about the assessment and management of common mental disorders in Australian general practice. SPHERE National Secretariat. Med J Aust. 2001;175(suppl):S52–S55. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koschera A, Hickie I, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Prolonged fatigue, anxiety and depression: Exploring relationships in a primary care sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:545–552. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, et al. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2006;333:575–580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38933.585764.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham PH, Browne L, Cox H, et al. Inhalation aromatherapy during radiotherapy: Results of a placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2372–2376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stockler MR, O'Connell R, Nowak AK, et al. Effect of sertraline on symptoms and survival in patients with advanced cancer, but without major depression: A placebo-controlled double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:603–612. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clover K, Leigh Carter G, Adams C, et al. Concurrent validity of the PSYCH-6, a very short scale for detecting anxiety and depression, among oncology outpatients. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:682–688. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ware JE., Jr Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, et al. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: New outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 1995. National Health Survey: SF-36 Population Norms Australia; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coates A, Porzsolt F, Osoba D. Quality of life in oncology practice: Prognostic value of EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in patients with advanced malignancy. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blatt MHG, Wiesbader H, Kupperman HS. Vitamin E and climacteric syndrome: Failure of effective control as measured by menopausal index. Arch Intern Med. 1953;91:792–799. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1953.00240180101012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alder E. The Blatt-Kupperman menopausal index: A critique. Maturitas. 1998;29:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:1311–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melby MK. Climacteric symptoms among Japanese women and men: Comparison of four symptom checklists. Climacteric. 2006;9:298–304. doi: 10.1080/13697130600868653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palacios S, Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, et al. Low-dose, vaginally administered estrogens may enhance local benefits of systemic therapy in the treatment of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women on hormone therapy. Maturitas. 2005;50:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Von Korff M, Ustun TB, Ormel J, et al. Self-report disability in an international primary care study of psychological illness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Young-McCaughan S. Sexual functioning in women with breast cancer after treatment with adjuvant therapy. Cancer Nurs. 1996;19:308–319. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speer JJ, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, et al. Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2005;11:440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, et al. Managing menopausal symp-toms in breast cancer survivors: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1054–1064. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Crespi CM, et al. Addressing intimacy and partner communication after breast cancer: A randomized controlled group intervention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0398-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The Sexual Activity Questionnaire: A measure of women's sexual functioning. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:81–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00435972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jensen PT, Klee MC, Thranov I, et al. Validation of a questionnaire for self-assessment of sexual function and vaginal changes after gynaecological cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:577–592. doi: 10.1002/pon.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]