Clinical information concerning diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment of 277 patients with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (including pancreatic tumors) diagnosed prospectively within 1 year were analyzed. Endoscopic and surgical techniques are the key to both correct diagnosis and effective treatment.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine tumors, Gastrointestinal tract, Diagnosis and treatment, Prospective clinical trial

Abstract

Background.

The aim of this prospectively collected, retrospectively analyzed clinical investigation was to describe “unmasked” clinical symptoms and methods of diagnosis, treatment, and short-term follow-up of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) diagnosed during 1 year in Austria.

Methods.

In total, 277 patients with GEP-NETs were documented. All tumors were immunhistochemically defined according to recently summarized criteria (World Health Organization, European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society). A standardized questionnaire comprising 50 clinical and biochemical parameters (clinical symptoms, mode of diagnosis, treatment, follow-up) was completed by attending physicians.

Results.

The most common initial symptoms were episodes of abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, flushing, and bowel obstruction. Overall, 48.1% of tumors were diagnosed by endoscopy, 43.7% were diagnosed during surgery, 5% were diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration of the primary or metastases, and 2.5% were diagnosed during autopsy; 44.5% of tumors were not suspected clinically and were diagnosed incidentally during various surgical procedures. Overall, 18.7% of tumors were removed endoscopically and 67.6% were removed surgically; 13.7% of patients were followed without interventional treatment. Endoscopic or surgical intervention was curative in 81.4% of patients and palliative in 18.6% of patients. At the time of diagnosis, information on metastasis was available in 83.7% of patients with malignant NETs. Lymph node or distant metastases were documented in 74.7% of patients. In 19.3% of patients, 41 secondary tumors were documented, with 78.0% classified histologically as adenocarcinomas.

Conclusion.

This investigation summarizes the clinical presentation and current practice of management of GEP-NETs and thereby extends the understanding and clinical experience.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of tumors arising from neuroendocrine cells and show distinct functional and biological behavior depending on location, tumor size, and clinical symptoms [1]. Correct histopathological diagnosis is key to adequate treatment [2], and it is crucial to classify lesions as NETs only if they stain immunohistochemically positive for chromogranin A and/or synaptophysin [2].

Although some NETs have a benign behavior, all are potentially malignant [1]. In a prospectively designed incidence study [3], 46% of NETs were classified as “well-differentiated benign” (World Health Organization [WHO] 2000 type 1a), 43% were classified as “well-differentiated benign/low-grade malignant with uncertain biological behavior” (WHO 2000 type 1b), and 39% were classified as showing malignant behavior (WHO 2000 type 2, well-differentiated/low-grade malignant carcinoma; WHO 2000 type 3, poorly differentiated/high-grade malignant carcinoma) [3, 4]. Using the tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) classification proposed by the European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) [5, 6], 11.0% were classified as stage III (lymph-node positive, regional disease) and 23.8% were classified as stage IV (metastasis positive, distant disease) [3]. Poorly differentiated (grade 3) tumors were found in 9.1% of cases [3].

The aim of the present prospectively collected, retrospectively analyzed clinical investigation was to describe “unmasked” clinical symptoms, diagnostic procedures, treatment, and short-term follow-up of precisely classified gastroenteropancreatic (GEP)-NETs. This approach documenting “everyday routine” should extend the knowledge and clinical experience of this rare tumor entity and should add cornerstones for earlier diagnosis and application of guidelines on treatment, thereby improving clinical outcome. Furthermore, risk stratification comparing the WHO 2000 and the new WHO 2010 classifications is demonstrated.

Methods

Background of Clinical Investigation

In a previous prospective trial to clarify the incidence of GEP-NETs in Austria, consecutive tumors histologically or immunhistochemically diagnosed and classified as NETs were documented in 285 patients during a 1-year period (May 1, 2004 to April 30, 2005) [3].

The site of the primary was the stomach in 65 (22.8%) patients, followed by the appendix (n = 59, 20.7%), small intestine excluding the duodenum (n = 44, 15.4%), rectum (n = 40, 15.4%), pancreas (n = 33, 11.6%), colon (n = 20, 7.0%), and duodenum (n = 16, 5.6%) [3].

In one patient each, the tumor was located in the esophagus, gallbladder, and Meckel diverticulum. Liver tumors expressing neuroendocrine markers were documented in five (1.7%) patients. These five tumors were categorized as metastases from NETs located in various sites of the gastrointestinal tract [2], with the location of the primary remaining unknown during the follow-up period. These eight patients were excluded from further analysis; thus, 277 (97.2%) patients generated the background of the detailed clinical analysis.

In the former study [3], 277 tumors were classified according to the WHO 2000 classification [1, 4]. Seventy-seven (27.9%) were graded according to ENETS 2006/2007 classification [5, 6]. Therefore, reclassification according the WHO 2010 classification [7] and, as an example, a comparison of the two classifications were performed.

In addition to the pathological report [3], details on the natural clinical course of the disease were requested in questionnaires comprising 50 clinical and biochemical parameters (clinical reports). The attending physicians were invited to participate in the multicenter study.

Informed Consent

All patients were asked for informed consent for their clinical data to be documented. The full names of the patients remained unknown to the study center.

Analysis and Presentation of Clinical Data

Patients were integrated into the clinical database only if they had agreed to participate in the study; thus, some could not be included. In addition, some questionnaires were incompletely filled out, lacking basic information. As a minimum requirement, information on the presence of metastasis (present/absent) and/or treatment had to be available for integration of a patient's data into the database. All available clinical parameters were included in a Filemaker® (Filemaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA) database (clinical database) and analyzed using SPSS®, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) software.

The clinical data are summarized in Tables 2–7. Because some questionnaires were returned incomplete (missing parameters for some patients), the tables also include a description of how often certain information was “available” or “unavailable” (missing information) to present data in a correct and objective manner (“data quality”).

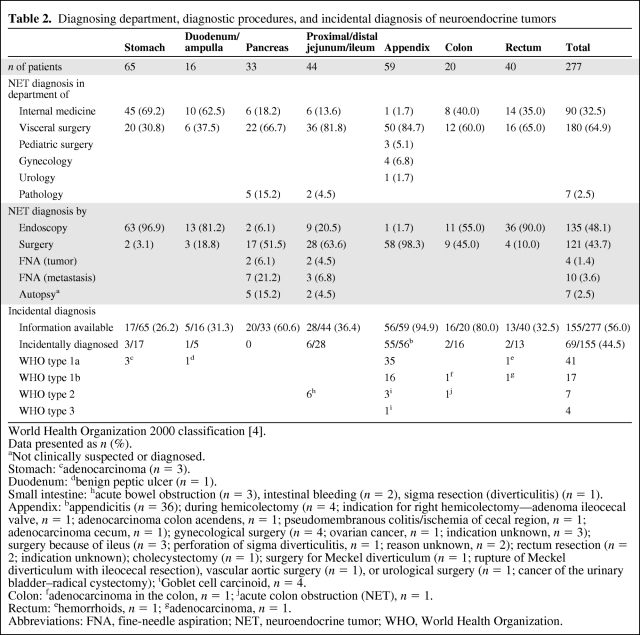

Table 2.

Diagnosing department, diagnostic procedures, and incidental diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors

World Health Organization 2000 classification [4].

Data presented as n (%).

aNot clinically suspected or diagnosed.

Stomach: cadenocarcinoma (n = 3).

Duodenum: dbenign peptic ulcer (n = 1).

Small intestine: hacute bowel obstruction (n = 3), intestinal bleeding (n = 2), sigma resection (diverticulitis) (n = 1).

Appendix: bappendicitis (n = 36); during hemicolectomy (n = 4; indication for right hemicolectomy—adenoma ileocecal valve, n = 1; adenocarcinoma colon acendens, n = 1; pseudomembranous colitis/ischemia of cecal region, n = 1; adenocarcinoma cecum, n = 1); gynecological surgery (n = 4; ovarian cancer, n = 1; indication unknown, n = 3); surgery because of ileus (n = 3; perforation of sigma diverticulitis, n = 1; reason unknown, n = 2); rectum resection (n = 2; indication unknown); cholecystectomy (n = 1); surgery for Meckel diverticulum (n = 1; rupture of Meckel diverticulum with ileocecal resection), vascular aortic surgery (n = 1), or urological surgery (n = 1; cancer of the urinary bladder–radical cystectomy); iGoblet cell carcinoid, n = 4.

Colon: fadenocarcinoma in the colon, n = 1; jacute colon obstruction (NET), n = 1.

Rectum: ehemorrhoids, n = 1; gadenocarcinoma, n = 1.

Abbreviations: FNA, fine-needle aspiration; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; WHO, World Health Organization.

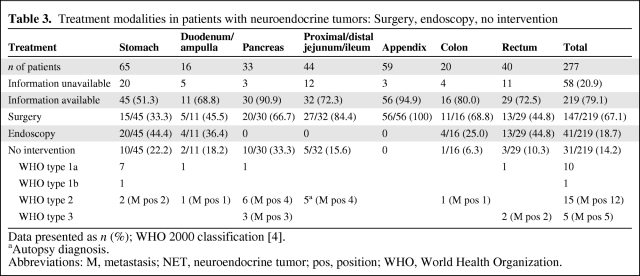

Table 3.

Treatment modalities in patients with neuroendocrine tumors: Surgery, endoscopy, no intervention

Data presented as n (%); WHO 2000 classification [4].

aAutopsy diagnosis.

Abbreviations: M, metastasis; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; pos, position; WHO, World Health Organization.

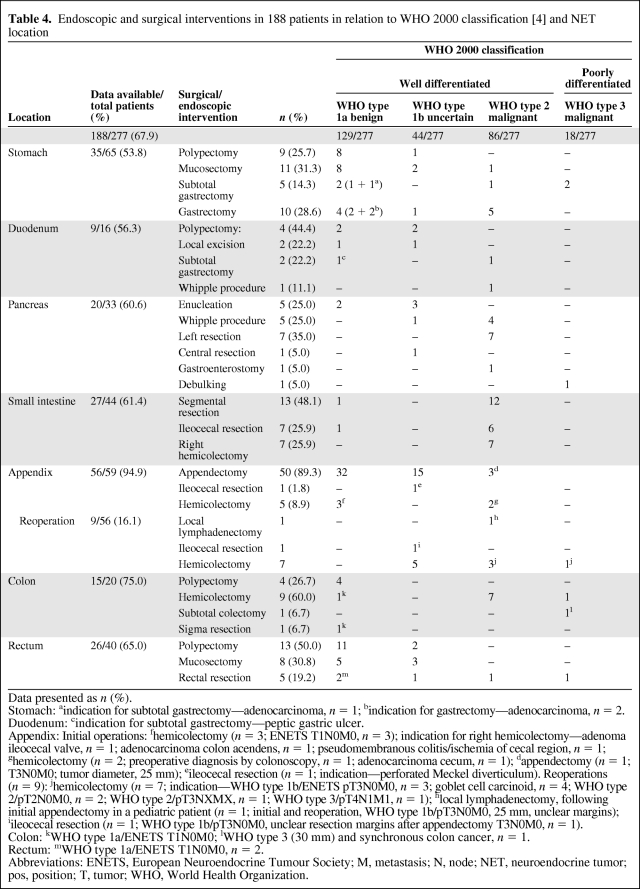

Table 4.

Endoscopic and surgical interventions in 188 patients in relation to WHO 2000 classification [4] and NET location

Data presented as n (%).

Stomach: aindication for subtotal gastrectomy—adenocarcinoma, n = 1; bindication for gastrectomy—adenocarcinoma, n = 2.

Duodenum: cindication for subtotal gastrectomy—peptic gastric ulcer.

Appendix: Initial operations: fhemicolectomy (n = 3; ENETS T1N0M0, n = 3); indication for right hemicolectomy—adenoma ileocecal valve, n = 1; adenocarcinoma colon acendens, n = 1; pseudomembranous colitis/ischemia of cecal region, n = 1; ghemicolectomy (n = 2; preoperative diagnosis by colonoscopy, n = 1; adenocarcinoma cecum, n = 1); dappendectomy (n = 1; T3N0M0; tumor diameter, 25 mm); eileocecal resection (n = 1; indication—perforated Meckel diverticulum). Reoperations (n = 9): jhemicolectomy (n = 7; indication—WHO type 1b/ENETS pT3N0M0, n = 3; goblet cell carcinoid, n = 4; WHO type 2/pT2N0M0, n = 2; WHO type 2/pT3NXMX, n = 1; WHO type 3/pT4N1M1, n = 1); hlocal lymphadenectomy, following initial appendectomy in a pediatric patient (n = 1; initial and reoperation, WHO type 1b/pT3N0M0, 25 mm, unclear margins); iileocecal resection (n = 1; WHO type 1b/pT3N0M0, unclear resection margins after appendectomy T3N0M0, n = 1).

Colon: kWHO type 1a/ENETS T1N0M0; lWHO type 3 (30 mm) and synchronous colon cancer, n = 1.

Rectum: mWHO type 1a/ENETS T1N0M0, n = 2.

Abbreviations: ENETS, European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society; M, metastasis; N, node; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; pos, position; T, tumor; WHO, World Health Organization.

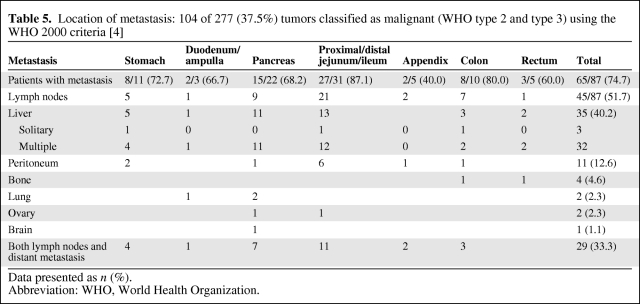

Table 5.

Location of metastasis: 104 of 277 (37.5%) tumors classified as malignant (WHO type 2 and type 3) using the WHO 2000 criteria [4]

Data presented as n (%).

Abbreviation: WHO, World Health Organization.

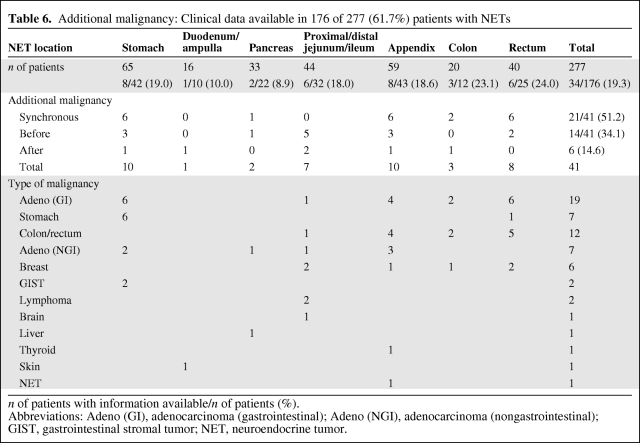

Table 6.

Additional malignancy: Clinical data available in 176 of 277 (61.7%) patients with NETs

n of patients with information available/n of patients (%).

Abbreviations: Adeno (GI), adenocarcinoma (gastrointestinal); Adeno (NGI), adenocarcinoma (nongastrointestinal); GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NET, neuroendocrine tumor.

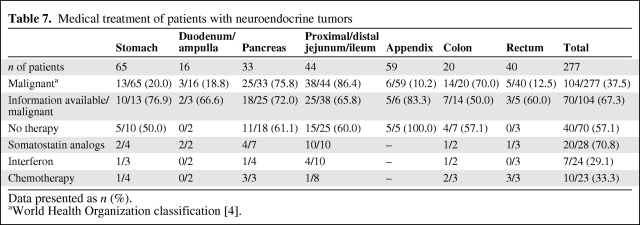

Table 7.

Medical treatment of patients with neuroendocrine tumors

Data presented as n (%).

aWorld Health Organization classification [4].

Ethics Committee Resolution

The prospective study design, manner of data collection, and retrospective analysis were approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (resolution number 157/2005).

Results

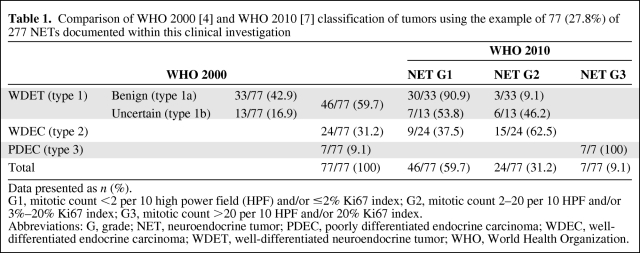

WHO 2000 Versus WHO 2010 Classification

According to the WHO 2000 classification [1, 4], 46 (59.7%) of 77 NETs in various locations were classified as well-differentiated endocrine tumors (benign, WHO type 1a, n = 33, 42.9%; uncertain, WHO type 1b, n = 13, 16.9%), 24 (31.2%) were classified as well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma, and seven (9.1%) were classified as poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma (Table 1). According to the current WHO 2010 classification [7], 46 (59.7%) of 77 tumors were reclassified as NET grade 1 (G1) (carcinoid), 24 (31.2%) were reclassified as NET G2, and seven (9.1%) were reclassified as neuroendocrine carcinoma (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of WHO 2000 [4] and WHO 2010 [7] classification of tumors using the example of 77 (27.8%) of 277 NETs documented within this clinical investigation

Data presented as n (%).

G1, mitotic count <2 per 10 high power field (HPF) and/or ≤2% Ki67 index; G2, mitotic count 2–20 per 10 HPF and/or 3%–20% Ki67 index; G3, mitotic count >20 per 10 HPF and/or 20% Ki67 index.

Abbreviations: G, grade; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; PDEC, poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma; WDEC, well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma; WDET, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor; WHO, World Health Organization.

Clinical Symptoms, Method of Diagnosis, Biochemical Data

The most common symptoms among 241 (87.0%) of the 277 patients analyzed were abdominal pain (71 of 241, 29.5%), diarrhea (21 of 241, 8.7%), weight loss (18 of 241, 7.5%), gastrointestinal bleeding (13 of 241, 5.4%), flushing (nine of 241, 3.7%), and bowel obstruction (eight of 241, 3.3%). Neurological and psychiatric symptoms were reported in five (2.1%) patients, among whom were three of 33 (9.1%) patients with pancreatic NETs. In two of these three patients, insulinomas may have been suspected clinically but were not confirmed biochemically because no specific functional tests were performed; an insulinoma was documented biochemically in the third patient. Diarrhea was the leading clinical symptom in one biochemically confirmed vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)oma. One other patient suffered from recurrent peptic ulcers. Gastrinoma may have been suspected clinically but was not confirmed biochemically because no “secretin tests” were applied.

The majority of tumors were diagnosed in departments of surgery (180 of 277, 64.9%), followed by departments of internal medicine (90 of 277, 32.5%). Seven tumors (pancreas, n = 5; small intestine, n = 2; 2.5%) not suspected clinically as NETs were eventually documented during autopsy.

As shown in Table 2, 135 (48.1%) of 277 tumors were diagnosed by endoscopy, 121 (43.7%) were diagnosed during surgery (see also Incidental Diagnosis), four (1.4%) were diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the primary, and 10 (3.6%) were diagnosed by FNA of metastases.

Biochemical data were available in 34 (12.3%) of the 277 analyzed patients. Specific laboratory tests (gastrin, insulin, C peptide, VIP, serotonin, 5-hydroxindole acetic acid, chromogranin A) were not routinely used. Elevated levels of gastrin were documented in all five WHO type 1a tumors of the stomach and in the two WHO type 1a tumors of the duodenum. Elevated hormone levels indicating functioning pancreatic NETs were documented in two patients: insulinoma (positive 48-hour fasting test) and VIPoma in one patient each. Elevated levels of 5-hydroxindole acetic acid were documented in the urine (carcinoid syndrome) of two of nine (22.2%) patients with tumors of the small intestine and liver metastases. One pancreatic NET was associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 syndrome (one of 112; 0.9%).

Treatment

In total, 147 (67.1%) tumors were treated surgically and 41 (18.7%) were treated endoscopically; 30 (13.7%) lesions were followed without interventional treatment (Table 3). As preparation for treatment of liver metastasis, one patient (0.5%) underwent cholecystectomy without treating the NET. Overall, details of interventions were documented in 188 of 277 patients (67.9%) (Table 4).

Stomach

Of 35 stomach tumors, 20 (57.1%) were removed endoscopically and 15 (42.9%) were removed surgically (Table 3). Stepwise biopsy of the gastric mucosa was performed in 38 of 65 (58.5%) patients. Details on the association of chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) type A were available in 38 (58.5%) patients; CAG was described in 32 (84.2%). Three NETs (all WHO 2000 type 1a) were diagnosed concomitantly with an adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

Endoscopic mucosectomy or polypectomy and subtotal or total gastrectomy were performed (Table 4). In three lesions classified as WHO 2000 type 1a/ENETS T1N0M0, the indication for subtotal (n = 1) or total (n = 2) gastrectomy was the NET (Table 4).

Duodenum

Nine (81.9%) of 11 duodenal tumors were removed endoscopically, five (45.5%) were removed surgically (Table 4).

Pancreas

Thirteen (50.0%) of 26 pancreatic tumors were localized in the pancreatic head, seven (26.9%) were localized in the pancreatic body, and six (23.1%) were localized in the pancreatic tail.

Left pancreatic resection was performed in seven of 20 (35.0%) patients. Whipple operation was performed in five patients (25.0%), tumor enucleation was performed in five patients (25.0%), central pancreatic resection was performed in one patient (5.0%), tumor debulking was performed in one patient (5.0%), and gastroenterostomy was performed in one patient (5.0%) (Table 4).

Small Intestine

Among 44 patients with small intestinal tumors, 27 (61.4%) were treated surgically. Small intestine segment resection, right hemicolectomy, and ileocecal resection were performed (Table 4). One patient underwent cholecystectomy without treatment of the NET (counted as “no intervention”).

Appendix

In 45 (88.2%) of 51 patients with appendiceal tumors, the tumor was located at the tip; in six (11.8%) it was located near or at the base of the appendix.

Interventions were documented in 56 of 59 (94.9%) patients: 47 (83.9%) had one surgical intervention and nine (16.1%) had reoperations after initial appendectomy (Table 3). During reoperations, hemicolectomy was performed in seven patients and ileocecal resection and local lymphadenectomy were performed in one patient each (Table 4).

Colon

Of 15 colonic tumors, 11 (73.3%) were removed surgically and four (26.7%) were removed endoscopically. Hemicolectomy, endoscopic polypectomy, subtotal colectomy, and sigma resection were performed (Table 4). In two cases, both classified as WHO type 1a/ENETS T1N0M0, the indication for hemicolectomy or sigma resection was the NET.

Rectum

Details on therapeutic procedures were available in 29 of 40 (72.5%) patients with rectal tumors: 13 (44.8%) were removed surgically, 13 (44.8%) were removed endoscopically. Endoscopical polypectomy, anterior rectal resection, and transanal resection (mucosectomy) were performed. In two patients, the indication for anterior rectal resection was the NET (Table 4).

Overall, 105 of 129 (81.4%) surgical interventions were intended to be curative, 24 (18.6%) were intended to be palliative.

Distant Metastasis

At the time of diagnosis, information concerning metastasis was available in 87 (83.7%) of the 104 patients with malignant NETs (Table 5). Sixty-five of 87 (74.7%) tumors had already metastasized. Patients with small intestinal malignant NETs had metastasis in 27 (87.1%) of 31 cases. Forty-five (51.7%) patients had metastasis in lymph nodes and 35 (40.2%) had metastasis in the liver. Both lymph node and distant metastases were documented in 29 of 87 patients (33.3%).

Additional Malignancy

Of the 277 patients analyzed, clinical data on additional malignancies were available in 176 (61.7%). Forty-one various tumors, their location, and the time of diagnosis are described in Table 6. Among these, 32 (78.0%) were classified histologically as adenocarcinomas: 19 (46.3%) localized in the colon or rectum, seven localized in the urogenital tract, and six (14.6%) localized in the breast (Table 6). Six of seven adenocarcinomas of the stomach were associated with NETs of the stomach and CAG.

Medical Treatment

Data on medical treatment were available for 70 of 104 (67.3%) patients with malignant tumors (Table 7). Forty (57.1%) patients did not receive medical treatment. Somatostatin analogs were used in 20 of 27 (74.1%) patients, interferon was used in seven of 23 (30.4%) patients, and chemotherapy was used in 10 of 22 (45.5%) patients.

Various treatment modalities were reported for 18 of 35 (51.4%) patients with liver metastases: ablation chemoembolization in 10 patients (55.6%), selective internal radiotherapy in four patients (22.2%), and radiofrequency ablation in one patient (5.6%). Peptide receptor radiotherapy was used in three of 17 patients (16.7%).

Follow-Up

One year after diagnosis, follow-up data were documented in 96 (34.7%) of the 277 analyzed patients: 59 (61.5%) showed no evidence of disease, 13 (13.5%) had stable disease, 16 (16.7%) had progression of disease, and eight patients (8.3%) died as a result of the NET. The patients with disease progression developed local recurrence in nine (9.4%) cases and new distant metastases in 15 (15.6%) cases.

Discussion

This analysis documents the clinical management of 277 consecutive patients with GEP-NETs precisely classified as NETs [2] and grouped according to the WHO 2000 classification [1, 4]. Additionally, in 181 (65.3%) patients the ENETS staging system [5, 6] and in 77 (27.9%) patients the ENETS grading system [5, 6] were applied.

The WHO 2000 classification [1, 4] in combination with the ENETS TNM classification and grading system [5, 6] serves as a basis for establishing criteria for practical management, especially in Europe [8]. Because of low acceptance of both systems in the U.S., the WHO developed a revised version for the classification of NETs. Taking all European and American arguments into account, the WHO 2010 classification [7] consists of a grading system that is combined with a site-specific staging system (identical to the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union Internationale Contre le Cancer TNM system; for details, see [7]). The WHO 2010 classification eliminates the clinically inefficient group of patients with tumors of uncertain behavior [9]. Based on the consideration that all NETS are malignant but may behave differently based on their specific grading [7], there were in fact minor changes in risk stratification when comparing the WHO 2000 and WHO 2010 classifications. Specifically, 53.8% of WHO 2000 type 1b tumors (uncertain clinical behavior) were shifted to NET G1 and 46.2% were changed to NET G2 and are now better risk stratified.

Because reclassification was impossible for all patients and because of the limited experience with the WHO 2010 classification, the combination of the WHO 2000 classification [1, 4] and the ENETS grading and staging system [5, 6] was used for presenting and discussing this clinical investigation. Because there are only marginal differences between the combination of the WHO 2000 classification [1, 4] and ENETS grading and staging system [5, 6] and the new WHO 2010 classification, the conclusions are valid for both the old and new classifications.

Most tumors were diagnosed using endoscopic techniques (48.1%). This high percentage is mainly a result of the fact that particular lesions in the stomach (96.9%), the rectum (90.0%), the duodenum (81.2%), and the colon (55.0%) were detected during endoscopy. Most of these tumors were small, benign, and incidental findings.

Unsuspected clinically as NETs, 43.7% were found during surgery, mainly located in the appendix (98.3%), small intestine (63.6%), pancreas (51.5%), and colon (45.0%). Only a minority was detected by FNA biopsy of the tumor itself (1.4%) or of a (liver) metastasis (3.6%).

Nonspecific symptoms (vague abdominal pain, weight loss) were evident in 37% of cases. Retrospectively, specific clinical symptoms, either local (e.g., local stenosis, melena) or systemic (e.g., diarrhea, flushing), were reported in 21.5% of patients. This is in accordance with earlier and current experience [10]. Landerholm et al. [11] reported that even patients with small bowel NETs with distant metastasis may present without symptoms, and the carcinoid syndrome is infrequently seen. Aggarwal et al. [12] therefore recommended that primary care physicians keep in mind NETs and their vague, nonspecific clinical features and start appropriate diagnostic testing early.

Only a small group of patients (12.3%) underwent comprehensive endocrine testing to confirm the functionality of the NETs. However, the absence of documented functionality does not exclude a hormonally active syndrome in many patients. On reviewing single-center reports from referral centers [13] and recently established national registries [14, 15], functioning tumors were reported in up to 40% of patients. Up to 49% localized in the small intestine [14, 16, 17] and up to 75% localized in the pancreas [9, 18] were functioning. In our study, the lack of more patients with functioning tumors and endocrine tumor syndromes in various sites (pancreas, ileum/jejunum) is surprising but reflects the “general” situation. Although clinical data were collected prospectively, it is not possible to determine whether pancreatic NETs are indeed mainly nonfunctioning or whether functioning tumors and tumor syndromes were not documented as such. Nevertheless, the low reporting of typical symptoms of hormonal activity may indicate a greater proportion of nonfunctioning tumors than previously assumed. The higher rates of functioning tumors in larger, mainly academic series may reflect a single-center effect [15].

More and more NETs in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract are treated successfully by various endoscopic techniques. Candidate tumors for endoscopic resection are localized and well-differentiated with a very low risk for metastasis [2]. Endoscopic excision of various tumors was performed in 18.6% of patients.

Typical surgical resections (with or without lymph node dissection) were performed in 67.8% of patients. The domain for radical surgical intervention (with or without additional treatment) is that of NETs localized in the pancreas, ileum/jejunum, and appendix, and in more advanced tumors in all locations with the intention of curative resection (ENETS stage 3) [2]. Palliative surgery may be considered in selected patients with well-differentiated low-grade carcinoma (ENETS stage 4) [2].

In the majority (81.4%) of patients, the surgical procedure was curative (R0). The high rate of curative procedures was influenced by the number of NETs localized in the appendix and classified as benign or uncertain. As an alternative to endoscopic or surgical treatment, medical treatment (somatostatin analogs, interferon, chemotherapy, or combinations of various regimens) was offered to 42.9% of patients, including patients with very advanced malignant disease. It is recommended that fast-growing, poorly differentiated tumors (WHO 2000 type 3, WHO 2010 neuroendocrine carcinoma) of all T classifications with lymph node and/or distant metastases are initially treated with chemotherapy [2].

Overall, distant metastases were demonstrated in 74.7% of all patients with malignant NETs. Because 51.7% of all patients with malignant tumors had metastasis in lymph nodes, a radical approach with lymph node dissection seems mandatory in surgical treatment. Of all malignant tumors, 40.2% had metastasized to the liver. It is well recognized that, at the time of initial diagnosis, multiple liver metastases may be present even though the primary localized in the digestive tract may be clinically silent [10].

According to the ENETS grading system [5, 6] and corresponding to the WHO 2010 classification [7], G3 tumors were diagnosed only in the colon, rectum, and pancreas. Although lymph node (35.5%) and distant (48.4%) metastases are diagnosed very early in the clinical course of ileum/jejunum NETs, all were graded G1 and G2, indicating an overall good prognosis. In the series reported by Landersholm et al. [11], metastasized tumors (regional, 44%; distant, 40%) were classified as WHO 2000 type 2.

Clinical presentation, tumor aggressiveness and metastatic potential, and the prognosis depend upon the primary location [19].

Stomach

According to the WHO [1], gastric NETs, heading the list of GEP-NETs [3], are classified into four biologically distinct types [20, 21]. Correct diagnosis and adequate treatment are based on precise classification and risk stratification [2]. However, in our study, not all 65 gastric NETs could be subdivided into type 1, 2, 3, or 4 according to the underlying pathophysiological stimulus [22] and morphology [20]. Gastrin levels were determined in only eight (12%) patients and hypergastrinemia was documented in five patients with WHO 2000 type 1a tumors. Type 1 tumors were suspected indirectly in 32 of 38 (84%) patients because CAG type A was documented histologically after stepwise biopsy of the gastric mucosa [23].

In accordance with the ENETS guidelines [8, 24], endoscopic polypectomy or mucosectomy was documented in 20 of 35 (57.1%) patients. This appears to have been adequate for 19 of the 20 patients; one patient underwent mucosectomy for a NET classified as a well-differentiated malignant tumor. Two patients with adenocarcinoma of the stomach underwent subtotal gastrectomy, with NETs (WHO 2000 type 1a) being diagnosed synchronously. Gastrectomy was performed in 10 patients; overtreatment may be discussed in three patients with only WHO 2000 type 1a and type 1b lesions.

Duodenum

Small duodenal tumors may be locally resected by endoscopy or surgery [24], as performed in six of nine patients. One well-differentiated carcinoma in the duodenal bulb was removed by distal gastric resection and one was removed by pancreatic head resection [24].

Pancreas

Functioning PNETs were suspected in only five of 33 (15.1%) patients. Biochemical parameters confirmed insulinoma and VIPoma in one patient each. Depending on the function, size, and location in the pancreas [2, 9], enucleation or major resections (with lymph node dissection for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes) were performed in five and 15 patients, respectively.

Jejunum/Ileum

Curative surgery is always recommended for jejunal/ileal tumors whenever feasible after careful symptomatic control of the clinical syndrome with somatostatin analogs [16]. Surgery of the primary should be performed as segmental resection, ileocecal resection, or right hemicolectomy with wide lymphadenectomy depending on the localization of the tumor [16]. These procedures were performed in 13 (46.6%), seven (25%), and seven (25%) of 28 patients, respectively. Curative surgery was achieved in 16 of 26 (61.5%) patients.

Appendix

NETs in the appendix rarely reach clinical significance. Apart from one patient (1.7%), all tumors (98.3%) were incidentally diagnosed histologically after appendectomy. Clinically, acute appendicitis was the indication for simple appendectomy in 89.2% of cases. Forty-seven (83.9%) of 56 patients had one surgical intervention. Reoperations were performed in nine (16.1%) patients: hemicolectomy in seven, ileocecal resection in one, and local lymphadenectomy in one. According to the ENETS guidelines [25, 26], the indication and extent of reoperation was justified in at least eight (88.9%) of these nine patients.

Colon and Rectum

NETs of the colon should be treated in a way similar to adenocarcinoma of the colon, with localized colectomy and radical lymphadenectomy [27]. This concept was used in 11 of 15 (73.3%) patients. The treatment of WHO type 1a and type 1b rectal NETs includes endoscopic polypectomy, transanal excision (mucosectomy), and extended resection [27, 28]. Minimally invasive techniques are safe and were performed in 21 of 26 (80.8%) NET patients. The extent of surgery seems not justified in the two patients with well-differentiated benign tumors and in the patient with a poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma. The poor prognosis of the latter is a result of frequent presentation with metastases at the time of first diagnosis and the relative lack of effective therapy [29]. Selected patients with regional disease (N0 or N1 M0) may benefit from surgery whereas those with distant disease (M1) are best treated initially with chemotherapy.

Additional Malignancy

Patients with GEP-NETs have up to a 46% risk for synchronous or metachronous neoplasia in various locations [30–32]. Thus, 41 malignant tumors were documented synchronously with, before, or after the diagnosis of the GEP-NET in 34 of 176 (19.3%) patients. Among these tumors, 19 (46.3%) were adenocarcinoma localized in the stomach, colon, or rectum. Patients with NETs in the rectum (24%) and colon (23.1%) had the highest rate of secondary primary malignancies, followed by those with NETs in the stomach (19.0%), appendix (18.6%), jejunum/ileum (18.0%), and pancreas (8.9%). This is in contrast to an analysis reporting patients with small intestinal NETs as having the highest rate of secondary primary malignancies, followed by those with appendiceal and colorectal NETs [33]. Among the additional malignancies, 21 of 41 (51.2%) were diagnosed synchronously with and 14 (34.1%) were diagnosed before the diagnosis of the NET. However, six (14.6%) secondary carcinomas were diagnosed within the first year after the NET diagnosis. In contrast to the conclusion of Brune et al. [34], long-term follow-up is recommended for patients with NETs, for both secondary malignancies and delayed metastasis.

Follow-Up

The follow-up time of 1 year is too short to analyze overall survival and calculate prognosis. However, after 1 year, 75.0% of patients showed no evidence of disease or had stable disease, 16.7% showed progression, and in 8.3% the NET was the cause of death. Only patients with tumors classified as well-differentiated or poorly differentiated carcinoma showed progression of disease or died, whereas no patients with NETs classified as benign or as having uncertain behavior showed local recurrence, had disease progression, or died.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Bettina Haidbauer for running the study secretariat and the members of the Austrian Society of Internal Medicine and Surgery for supporting this national study.

This manuscript is the second part of M. B. Niederle's doctoral thesis, entitled Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Digestive Tract in Austria (N090 Endocrinology and Metabolism), for obtaining the academic title Doctor of Medical Science at the Medical University of Vienna.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Martin B. Niederle, Bruno Niederle

Collection and/or assembly of data: Martin B. Niederle

Data analysis and interpretation: Martin B. Niederle

Manuscript writing: Martin B. Niederle

Final approval of manuscript: Bruno Niederle

References

- 1.Klöppel G, Perren A, Heitz PU. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: The WHO classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:13–27. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klöppel G, Couvelard A, Perren A, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Towards a standardized approach to the diagnosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and their prognostic stratification. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;90:162–166. doi: 10.1159/000182196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederle MB, Hackl M, Kaserer K, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: The current incidence and staging based on the WHO and European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society classification: An analysis based on prospectively collected parameters. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:909–918. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solcia E, Kloppel G, Sobin L, editors. Berlin: Springer; 2000. Histological Typing of Endocrine Tumours, Second Edition. World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumours; pp. 1–156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rindi G, Klöppel G, Alhman H, et al. TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: A consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rindi G, Klöppel G, Couvelard A, et al. TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: A consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:757–762. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosman F, Carneiro F, Hruban R, et al., editors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System; pp. 1–418. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruszniewski P, Delle Fave G, Cadiot G, et al. Well-differentiated gastric tumors/carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:158–164. doi: 10.1159/000098007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schindl M, Kaczirek K, Kaserer K, et al. Is the new classification of neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors of clinical help? World J Surg. 2000;24:1312–1318. doi: 10.1007/s002680010217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schindl M, Kaczirek K, Passler C, et al. Treatment of small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors: Is an extended multimodal approach justified? World J Surg. 2002;26:976–984. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landerholm K, Falkmer S, Järhult J. Epidemiology of small bowel carcinoids in a defined population. World J Surg. 2010;34:1500–1505. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0519-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal G, Obideen K, Wehbi M. Carcinoid tumors: What should increase our suspicion? Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:849–855. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75a.08002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pape UF, Böhmig M, Berndt U, et al. Survival and clinical outcome of patients with neuroendocrine tumors of the gastroenteropancreatic tract in a German referral center. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:222–233. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lombard-Bohas C, Mitry E, O'Toole D, et al. Thirteen-month registration of patients with gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumours in France. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89:217–222. doi: 10.1159/000151562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ploeckinger U, Kloeppel G, Wiedenmann B, et al. The German NET-registry: An audit on the diagnosis and therapy of neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;90:349–363. doi: 10.1159/000242109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksson B, Klöppel G, Krenning E, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumors–well-differentiated jejunal-ileal tumor/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:8–19. doi: 10.1159/000111034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall JB, Bodnarchuk G. Carcinoid tumors of the gut. Our experience over three decades and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;16:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, et al. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: Epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:409–427. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinchot SN, Holen K, Sippel RS, et al. Carcinoid tumors. The Oncologist. 2008;13:1255–1269. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klöppel G, Clemens A. The biological relevance of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:69–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, et al. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: A clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:994–1006. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90266-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borch K, Ahrén B, Ahlman H, et al. Gastric carcinoids: Biologic behavior and prognosis after differentiated treatment in relation to type. Ann Surg. 2005;242:64–73. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167862.52309.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schindl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors: The necessity of a type-adapted treatment. Arch Surg. 2001;136:49–54. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plöckinger U, Rindi G, Arnold R, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine gastrointestinal tumours. A consensus statement on behalf of the European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80:394–424. doi: 10.1159/000085237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deschamps L, Couvelard A. Endocrine tumors of the appendix: A pathologic review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:871–875. doi: 10.5858/134.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plöckinger U, Couvelard A, Falconi M, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumours: Well-differentiated tumour/carcinoma of the appendix and goblet cell carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:20–30. doi: 10.1159/000109876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramage JK, Goretzki PE, Manfredi R, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumours: Well-differentiated colon and rectum tumour/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:31–39. doi: 10.1159/000111036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schindl M, Niederle B, Häfner M, et al. Stage-dependent therapy of rectal carcinoid tumors. W J Surg. 1998;22:628–633. doi: 10.1007/s002689900445. discussion 634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahlman H, Nilsson O, McNicol AM, et al. Poorly-differentiated endocrine carcinomas of midgut and hindgut origin. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:40–46. doi: 10.1159/000109976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fendrich V, Waldmann J, Bartsch DK, et al. Multiple primary malignancies in patients with sporadic pancreatic endocrine tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:592–595. doi: 10.1002/jso.21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habal N, Sims C, Bilchik AJ. Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors and second primary malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2000;75:310–316. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200012)75:4<306::aid-jso14>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tichansky DS, Cagir B, Borrazzo E, et al. Risk of second cancers in patients with colorectal carcinoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6119-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li AF, Hsu CY, Li A, et al. A 35-year retrospective study of carcinoid tumors in Taiwan: Differences in distribution with a high probability of associated second primary malignancies. Cancer. 2008;112:274–283. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brune M, Gerdes B, Koller M, et al. [Neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract (NETGI) and second primary malignancies—which is dominant?] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2003;128:2413–2417. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]