Src structure and function, mechanisms involving Src that lead to the development of cancer, and key preclinical data establishing a rationale for clinical application are reviewed. Clinical trials investigating new biomarkers as well as ongoing studies assessing Src inhibitor activity in biomarker-selected patient populations are highlighted.

Keywords: Biologic, Bosutinib, Dasatinib, Saracatinib, Solid tumor, Src inhibitors

Abstract

Summary.

Src is believed to play an important role in cancer, and several agents targeting Src are in clinical development.

Design.

We reviewed Src structure and function and preclinical data supporting its role in the development of cancer via a PubMed search. We conducted an extensive review of Src inhibitors by searching abstracts from major oncology meeting databases in the last 3 years and by comprehensively reviewing ongoing clinical trials on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Results.

In this manuscript, we briefly review Src structure and function, mechanisms involving Src that lead to the development of cancer, and Src inhibitors and key preclinical data establishing a rationale for clinical application. We then focus on clinical data supporting their use in solid tumor malignancies, a newer arena than their more well-established hematologic applications. Particularly highlighted are clinical trials investigating new biomarkers as well as ongoing studies assessing Src inhibitor activity in biomarker-selected patient populations. We also review newer investigational Src-targeting agents.

Conclusions.

Src inhibitors have shown little activity in monotherapy trials in unselected solid tumor patient populations. Combination studies and biomarker-driven clinical trials are under way.

Introduction

Src was the first proto-oncogene identified from the human genome and encodes a non–receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK). The origins of the discovery of Src began in the early 1900s when Francis Peyton Rous proposed that viruses could cause cancer [1]. He injected centrifuged chicken sarcoma material into chicks that later developed sarcomas themselves. This cancer-causing substance was later found to contain a retrovirus, later named the Rous sarcoma virus [2]. The gene implicated, viral-Src (v-Src), was identified in 1970 [3]. Bishop and Varmus won the Nobel Prize in 1989 for their work showing that the virus actually acquired the cancer-causing gene from a normal cellular gene, cellular-Src (or c-Src, hereafter referred to as Src) [4–6]. In normal tissues, Src's regulatory functions are multiple and include participation in fibroblast cell division and cell–cell adhesion regulation via modulation of integrins. Consequently, its overexpression is believed to play an important role in cancer progression, and several agents targeting Src are in clinical development. In this manuscript we review Src-targeting agents, focusing on new data in solid tumor malignancies.

The Src protein is one of the Src family kinases (SFKs), reviewed in detail by both Yeatman [7] and Thomas and Brugge [8]. There have been 12 SFKs identified: c-Src, Fyn, Yes, Yrk, Lyn, Hck, Fgr, Blk, Lck, Brk, Srm, and Frk (with Frk/Rak and Iyk/Bsk subfamilies), 11 of which are found in humans [8–12]. Src, Fyn, and Yes are expressed ubiquitously, with Src being expressed at five to 200 times higher levels in platelets, neurons, and osteoclasts [13]. The Src protein consists of a 12-carbon myristoyl group attached to the N-terminal domain, followed by a unique domain, SH3 and SH2 domains, an SH2-kinase linker domain, a protein kinase catalytic domain (or SH1 domain), and a negative regulatory C-terminal tail domain [7]. The SH3 domain is noncatalytic and thought to mediate protein–protein interactions responsible for localization and recruitment of substrates [8]. SH2 interacts with proteins such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and CRK associated substrate (CAS). The unique domain shows the greatest amount of sequence divergence among family members whereas the SH1 catalytic domain is well conserved.

Src is a non-RTK, and its activity mainly occurs at the inner leaflet of the cell because membrane localization is required for receptor-mediated signaling to occur. Src is thought to facilitate motility and invasion of tumor cells by promoting endocytosis of cell–cell adhesions [14], mediating assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions [15], and regulating expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that contribute to breakdown of the extracellular matrix [16, 17]. Src is also thought to activate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3, an important protein that mediates angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) activation [18].

Src interacts with several important RTKs, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), fibroblast growth factor receptor, hepatocyte growth factor receptor, colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R), insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/Neu, and stem cell factor receptor (c-Kit) [19–26]. The relationship of Src and the transmembrane RTKs is a complex, bidirectional process [27]. When the RTKs are activated, several intracellular proteins are necessary for signal propagation to the nucleus, and Src is one of these important protein mediators [8]. Src also acts to modulate the function of the RTKs [8]. EGFR and Src, for instance, appear to have a synergistic effect whereby higher levels of the combination of the two proteins demonstrate greater tumorigenesis than with either alone [28–31].

Involvement of SFKs in Cancers

SFKs have been shown to be involved in numerous human cancers (reviewed in detail by Summy and Gallick [32]). Colon cancer is the most extensively studied cancer related to Src, but others identified include breast cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer, brain cancer, melanoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and lymphoproliferative disorders (myelomas, leukemias, lymphomas) [32, 33].

In colon cancer, an early study by Bolen et al. [34] showed elevated Src activity in colonic carcinoma cell lines and tumors. Higher levels of kinase activity were noted in primary colonic tumors than in precancerous polyps, and a similar result was found for hepatic metastases versus primary tumors [35]. However, despite these findings, some evidence shows that Src kinase activity is actually higher in the earlier stages of cancer progression. The discrepancy of these data could be explained by the observation that Src contributes to the metastatic phenotype but is not required at all stages of cancer progression [32]. Despite this discrepancy, Src appears to be an independent prognostic indicator at all stages of colon carcinoma [36]. For upper gastrointestinal tumors, Src kinase activity was higher in eight of 10 gastric carcinomas than in normal mucosa [37], and three- to six-fold higher in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinomas than in controls [38, 39]. Several other cancers also show involvement by either Src or other SFK members. Src expression was found in 20 of 33 tumor samples of small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), in 60%–80% of adenocarcinomas and bronchioalveolar carcinomas and 50% of squamous cell carcinomas. Poorly differentiated lung cancers had higher Src expression levels than moderately to well-differentiated ones [40].

Several studies have demonstrated involvement of SFKs in the development of breast cancer as well. Elevated levels of Src have been noted in breast carcinoma cell lines [41, 42]. Src also plays a role in ErbB-2–mediated breast cancer, for which two mechanisms have been proposed. One mechanism involves ErbB-2 upregulation of Src translation by activating the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 pathway. The second describes stabilization of Src through inhibition of calpain protease–mediated Src degradation, leading to upregulated Src protein levels. Interestingly, Src inhibition was associated with dramatically lower ErbB-2–mediated breast cancer cell invasion in vitro and in animal models [43].

Src protein levels were also found to be elevated in both pancreatic tumors and cell lines [44]. Src inhibitors inhibit the growth of human pancreas tumor explants in preclinical models [45, 46]. Activated Src also increases levels of IGF-1R with a subsequent increase in IGF-dependent cell proliferation [47].

Src Inhibitors

With the wealth of literature supporting the role of Src in tumor progression, invasion, and metastasis, efforts have been under way in developing inhibitors of this non-RTK. Different classes of Src inhibitors have been developed, with several of these drugs showing promise in completed and ongoing clinical trials. Although selective Src inhibitors have been developed, dual inhibitors of Src and Bcr-Abl have been the compounds investigated for efficacy in patients. One such inhibitor, dasatinib, has U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for second-line therapy in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients. Here, we focus on the application of these inhibitors in the treatment of patients with solid tumors.

Dasatinib

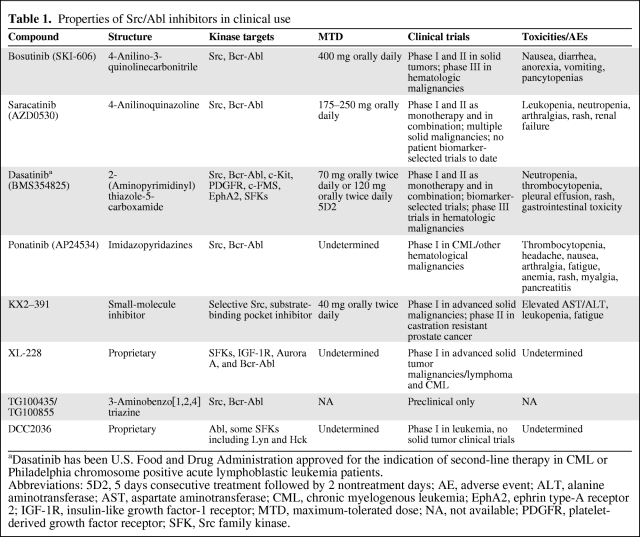

Dasatinib (BMS-354825; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York) is an orally bioavailable, ATP-site competitive 2-(aminopyrimididinyl)thiazole-5-carboxamide that is the only FDA-approved Src-Abl inhibitor for use in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) failing first-line therapy with imatinib. Recently, in a study of 512 patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase CML, Kantarjian et al. [48] demonstrated that, compared with imatinib as first-line treatment, dasatinib achieved higher rates of complete cytogenetic response, response in a shorter time, and lower rates of progression to accelerated or blastic phase. It is the most well-studied Src-Abl inhibitor, displaying a 325-fold greater potency for Bcr-Abl inhibition than imatinib. It is fairly unselective, inhibiting an array of additional downstream tyrosine kinases including c-Kit, c-FMS, ephrin type-A receptor 2 (EphA2), and PDGFR. The contribution of other kinase inhibitory activity to clinical efficacy remains a significant unknown (Table 1).

Table 1.

Properties of Src/Abl inhibitors in clinical use

aDasatinib has been U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved for the indication of second-line therapy in CML or Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients.

Abbreviations: 5D2, 5 days consecutive treatment followed by 2 nontreatment days; AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; EphA2, ephrin type-A receptor 2; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; MTD, maximum-tolerated dose; NA, not available; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; SFK, Src family kinase.

Preclinical data demonstrated the activity of dasatinib against several solid tumors. Src pathway inhibition has been shown in prostate cancer, head and neck cancer, NSCLC, colon cancer, and sarcoma cell lines [49–52]. Dasatinib was shown to induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in mesothelioma and EGFR-mutant lung cancer cell lines, corresponding with decreases in STAT-3 and Akt [53, 54]. Other studies reported sensitivity to dasatinib in difficult-to-treat breast cancer cell lines displaying the triple-negative or basal subtypes [55, 56], a small tumor size and fewer metastases in pancreatic xenografts [57], and lower rates of proliferation, migration, and invasion in melanoma cell lines [58].

Safety data from phase I studies with dasatinib as monotherapy in advanced solid tumors demonstrated a maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) of 120 mg twice daily for five treatment days followed by two nontreatment days or 70 mg twice daily continuously. Major toxicities included nausea, fatigue, and rash, but the overall clinical experience indicated that dasatinib is generally well tolerated. Variable bone marrow suppression was noted, although much less so than in hematologic malignancies [59]. In combination phase I studies, dasatinib was investigated with erlotinib (an EGFR inhibitor) for NSCLC [60] and 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) plus cetuximab [61] for metastatic colon cancer, and toxicities similar to those above were shown, with headache and other gastrointestinal symptoms as additional commonly reported adverse events (AEs) (Table 1).

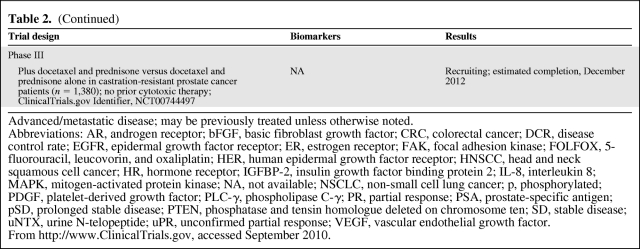

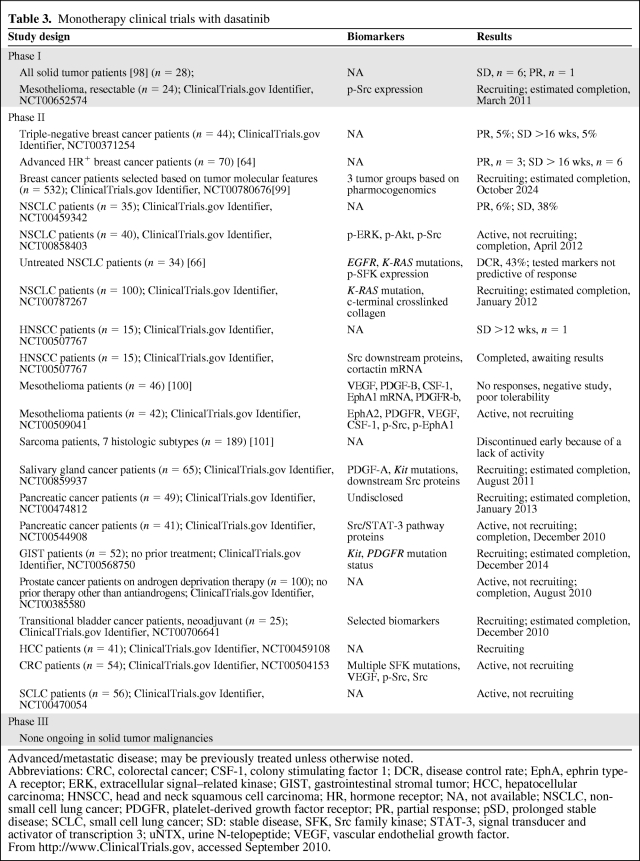

Though the largest body of clinical data with dasatinib is also in hematologic malignancies, promising preclinical data on solid tumor malignancies prompted many phase I and phase II solid tumor clinical studies. Ongoing trials with dasatinib as both monotherapy and in combination with other therapies are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. With preclinical data supporting the role of Src inhibition in osteoclast suppression, it is no surprise that cancers with a predilection for bony metastases, such as prostate and breast cancer, are rational and appealing targets. A phase II study of dasatinib in chemotherapy-naïve men with castration-resistant prostate cancer demonstrated 43% and 19% stable disease (SD) rates at 12 weeks and 24 weeks of treatment, respectively. Additionally, a reduction in N-telopeptide in the urine, an accepted marker of bone resorption predictive of adverse skeletal events, was also noted in 80% of the study patients with known bony metastases [62]. A phase I/II trial of dasatinib combined with docetaxel showed no significant drug–drug interactions and manageable toxicities, and 21 of 21 patients demonstrated a partial response (PR) or SD at >6–21 weeks of follow-up [63]. These data led to the initiation of a phase III double-blinded, randomized interventional trial in this patient population comparing dasatinib plus docetaxel with placebo plus docetaxel, with a primary endpoint measure of overall survival. That study is currently recruiting. In a phase II study of dasatinib in hormone receptor (HR)+ advanced breast cancer, 19% of patients had controlled disease at ≥16 weeks, although significant AEs led to a dose reduction from 100 mg twice daily to 70 mg twice daily [64].

Table 2.

Combination clinical trials with dasatinib

Table 2a.

(Continued)

Advanced/metastatic disease; may be previously treated unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: AR, androgen receptor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CRC, colorectal cancer; DCR, disease control rate; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FOLFOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell cancer; HR, hormone receptor; IGFBP-2, insulin growth factor binding protein 2; IL-8, interleukin 8; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NA, not available; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; p, phosphorylated; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PLC-γ, phospholipase C-γ; PR, partial response; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; pSD, prolonged stable disease; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome ten; SD, stable disease; uNTX, urine N-telopeptide; uPR, unconfirmed partial response; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

From http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed September 2010.

Table 3.

Monotherapy clinical trials with dasatinib

Advanced/metastatic disease; may be previously treated unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; CSF-1, colony stimulating factor 1; DCR, disease control rate; EphA, ephrin type-A receptor; ERK, extracellular signal–related kinase; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hormone receptor; NA, not available; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PR, partial response; pSD, prolonged stable disease; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SD: stable disease, SFK, Src family kinase; STAT-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; uNTX, urine N-telopeptide; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

From http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed September 2010.

There have also been combination therapy trials that have shown promising results in both melanoma and colorectal cancer patients. A phase II trial of dasatinib in combination with dacarbazine in 49 patients with metastatic melanoma yielded an overall 59.2% clinical benefit rate, defined as complete response (CR) + PR + SD by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, with four PRs and 25 patients with prolonged SD [65]. Src and phosphorylated (p)-Src levels in treated patient tumor blocks have not yet been reported, nor have biomarker analyses with B-RAF and c-Kit mutational status. Additional promising clinical data were observed in colorectal cancer patients who were refractory to initial FOLFOX therapy. In a phase I study of 30 patients treated with dasatinib in combination with cetuximab and FOLFOX, 24% of patients achieved a PR, including a 17% PR rate in patients previously reported to be refractory to dual therapy with FOLFOX and cetuximab [61]. These data prompted recruitment for a phase II, two-stage study that is currently under way (Tables 2 and 3).

Dasatinib as monotherapy has been less successful in early clinical trials, showing no significant clinical benefit in patients with high-grade glioma, mesothelioma, and sarcoma, despite encouraging preclinical data in these cancers. There was some benefit observed in a phase II trial studying dasatinib as first-line monotherapy for NSCLC patients, yielding a 43% disease control rate; however, this efficacy rate was lower than that of standard first-line chemotherapy. Biomarker analysis with EGFR and K-RAS mutation status was studied in these patients but did not predict response [66]. In addition to these early clinical data, phase II trials studying dasatinib as monotherapy are currently in progress for patients with advanced NSCLC, triple-negative breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), prostate cancer, and pancreatic cancer. Many phase I and phase II trials studying dasatinib in combination with other agents are also in progress for other cancers, including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and glioblastoma (Tables 2 and 3).

Saracatinib

Saracatinib (AZD0530; AstraZeneca, Wilmington, DE) is another orally active, highly selective, small-molecule, dual Src-Abl inhibitor that has shown promising results in preclinical and clinical studies mainly focused on solid tumors and osteolytic lesions. Antitumor effects have been observed in various solid tumor cell lines, including breast, prostate, and lung cancers. Inhibition of migration and cell invasion with saracatinib was demonstrated as well. In preclinical breast cancer studies, saracatinib in combination with antiestrogen therapy, such as tamoxifen, resulted in lower levels of Src, FAK, Akt, paxillin, CAS, cyclin D1, and c-Myc and helped prevent acquired antihormone resistance [67]. In tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cell lines, the combination of saracatinib and gefitinib, an EGFR inhibitor added because of the higher levels of EGFR in tamoxifen-resistant cells, showed greater cell adhesion and less invasiveness [67]. Studies of prostate cancer cell lines demonstrated similarly lower levels of many of the above proteins [68]. Another study showed lower levels of interleukin 8, urokinase plasminogen activator, and MMP-9, which might retard osteolytic bone metastases. In lung cancer cell models, saracatinib inhibited downstream signaling through FAK and Akt, and demonstrated radiosensitization [69]. Results similar to those from the above studies were reported in colon cancer, head and neck cancer, and lymphoma cell lines [70–72]. Data showing the efficacy of saracatinib in reducing metastatic disease were seen in a murine metastatic model of bladder cancer in which there was a significantly lower number of tumor colonies that could be grown from mesenteric lymph node extracts in treated than in untreated mice [73].

Several phase I clinical trials of saracatinib have been conducted and an MTD of 175 mg daily has been established for advanced solid tumor malignancies. Dose-limiting toxicities included cytopenias, asthenia, and respiratory failure [74]. Other reported mild AEs included nausea, anorexia, myalgias, cough, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia (Table 1).

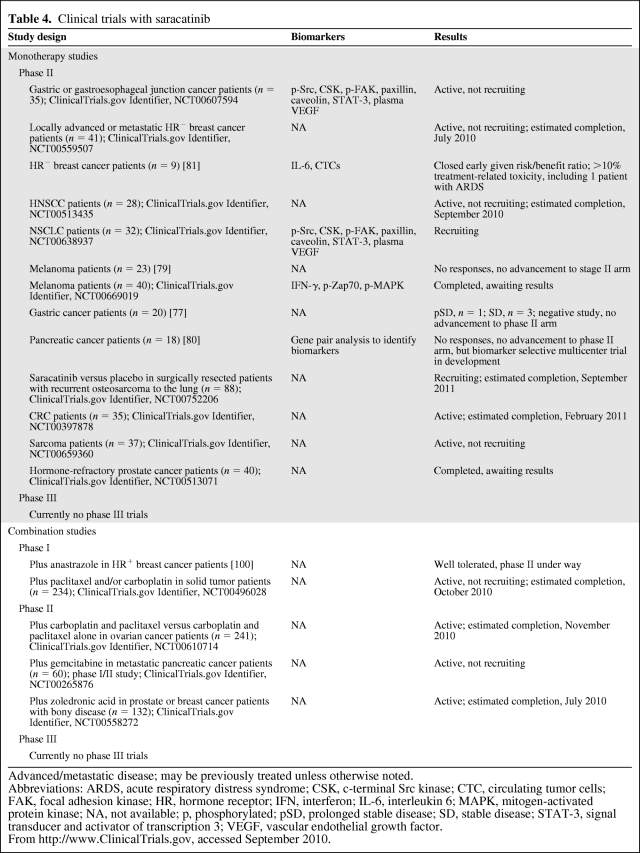

Saracatinib has had limited efficacy in phase II clinical trials in many human solid tumor malignancies. Single-agent studies in pancreatic cancer, HNSCC, HR− breast carcinoma, melanoma, prostate cancer, and gastric cancer patients have all been negative [75–81]. Phase II monotherapy studies currently in progress or recruiting patients include those for small cell lung cancer, metastatic colorectal cancer, sarcoma, and metastatic prostate or breast cancer with evidence of bony disease involvement. A large phase II study examining additional benefit for ovarian cancer patients treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel recently completed and was also negative [82]. Despite the lack of success in clinical trials to date, it is important to note that all clinical trials studying the efficacy of Src inhibitors have been conducted in unselected patients. Many trials with Src inhibitors, including saracatinib, are investigating possible biomarkers of response that may provide a selected population of patients who are more likely to benefit from treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical trials with saracatinib

Advanced/metastatic disease; may be previously treated unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CSK, c-terminal Src kinase; CTC, circulating tumor cells; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; HR, hormone receptor; IFN, interferon; IL-6, interleukin 6; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NA, not available; p, phosphorylated; pSD, prolonged stable disease; SD, stable disease; STAT-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

From http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed September 2010.

Bosutinib

Bosutinib (SKI-606; Wyeth/Pfizer, New York, NY) is a 4-anilino-3-quinolinecarbonitrile and a potent, orally administered, small-molecule inhibitor of both Src and Abl tyrosine kinases. It displays 200-fold more potent inhibition of Bcr-Abl than imatinib. In breast cancer cell lines, bosutinib was shown to reduce cell proliferation, invasion, and migration by inhibiting mitogen-activated protein kinase and Akt phosphorylation [83]. In colorectal cancer, bosutinib also promoted cytosolic localization of β-catenin, leading to greater binding affinity to E-cadherin, resulting in greater adhesion of colorectal cancer cells and less motility [84]. Similarly, bosutinib demonstrated slower growth in HT29 xenograft models [85].

A phase I study of 51 patients with advanced solid tumors showed that bosutinib was generally well tolerated, with predominantly gastrointestinal AEs in 19%–69% of patients in three reports. The MTD was determined to be 400 mg daily. Study of a restricted cohort of pancreatic cancer, NSCLC, and colorectal cancer patients is ongoing [86]. Phase I/II studies in CML and Ph+ ALL patients who failed imatinib showed similar AEs as well as some mild dermatologic symptoms and variable hematologic toxicity [87, 88] (Table 1).

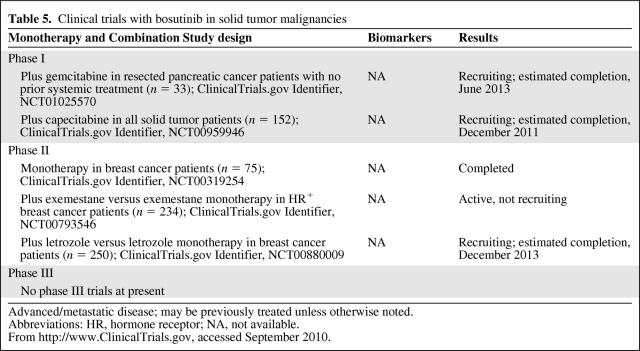

Although the body of clinical data supporting bosutinib has also been primarily applied to hematological malignancies, there are phase II trials in progress to study its efficacy in solid malignancies as well. Two phase II trials are examining HR+ breast cancer patients treated with an aromatase inhibitor with or without the addition of bosutinib to determine if there is added clinical benefit. Another phase II study is exploring the use of bosutinib in pancreatic adenocarcinoma in combination with gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected disease. Results of these studies are not yet available (Table 5).

Table 5.

Clinical trials with bosutinib in solid tumor malignancies

Advanced/metastatic disease; may be previously treated unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: HR, hormone receptor; NA, not available.

From http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed September 2010.

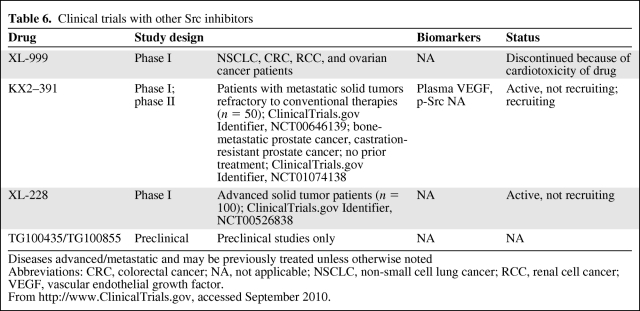

Other Inhibitors

KX2–391 (Keryx Biopharmaceuticals; Buffalo, NY) is a novel Src inhibitor that targets the peptide substrate–binding site instead of the ATP-binding site mechanism that is common to other Src inhibitors. KX2–391 has a much wider spectrum of solid tumor activity in vitro and is more potent in mouse xenografts than other multikinase Src/Abl inhibitors. A phase I study in advanced solid tumor malignancies demonstrated dose-limiting toxicities of elevated transaminases, neutropenia, and fatigue, all of which were reversible within 7 days. In that study, the MTD was found to be 40 mg twice daily. Phase I data in all solid tumors demonstrated biologic activity in pancreatic and prostate cancer patients, leading to a phase II trial in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients [89] (Table 6). Of note, KX2–391 also inhibits microtubule polymerization, so the mechanism of action is somewhat unclear.

Table 6.

Clinical trials with other Src inhibitors

Diseases advanced/metastatic and may be previously treated unless otherwise noted

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; NA, not applicable; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; RCC, renal cell cancer; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

From http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed September 2010.

XL228 (Exelixis Pharmaceuticals, San Francisco, CA) is currently being studied in a phase I trial for the treatment of patients with CML or Ph+ ALL as well in a phase I trial for patients with all other types of unresectable, advanced solid tumor malignancies and lymphoma (Table 6).

Other inhibitors in development, which are in preclinical stages only, include DCC-2036 (Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Lawrence, KS), an Abl inhibitor that also inhibits two of the SFKs; ponatinib (AP24534; ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cambridge, MA), the phase I results of which were recently presented [90]; and TG100435 (TargeGen, San Diego, CA), a 3-aminobenzotriazine compound (Table 6).

Biomarkers in Src-Targeted Therapies

Biomarkers predictive of response to a targeted therapy are an attractive area of investigation because these agents have limited success in unselected populations. Although many downstream effectors of the Src pathway appear to be downregulated with treatment in cell line models, whether these reductions translate into treatment benefit is unclear. Preclinical studies on papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines showed no correlation between p-Src levels and response to saracatinib, but high levels of p-FAK were strongly correlated with saracatinib sensitivity. These data suggest that p-FAK may be a better predictive biomarker in thyroid cancer than p-Src [91]. In the clinical arena, biomarkers established in preclinical work are currently being measured in pre- and post-treatment samples to determine whether high expression in pretreatment patients predicts response and whether that response is correlated with a corresponding decrease in biomarker levels. These results hopefully will identify subpopulations who are more likely to benefit from treatment. Most of the clinical trials incorporating a biomarker investigation are studies with dasatinib. Candidate biomarkers in these trials include STAT-3, cortactin, c-Kit, b-Raf, VEGF, CSF-1, EphA1 mRNA, EphA2, p-Src, and other phosphorylated downstream SFK effectors in various cancers. Biomarker investigations in clinical trials with dasatinib and saracatinib are summarized in Tables 2–4.

Other studies are screening for genetic markers as predictors of response. Those studies also primarily examined dasatinib. To date, clinical trials of selected patients based on such genetic biomarkers include a breast cancer trial of dasatinib in selected patients based on gene-expression profiling of three distinct biomarkers that were identified in sensitive versus resistant breast cancer biopsy specimens [92]. Similarly, a phase II study in prostate cancer patients is under way that selects patients based on genomic evaluation of androgen receptor (AR) activity, whereby patients with high AR profiles are assigned to hormonal therapy with nilutamide and those with low AR profiles are assigned to dasatinib. That trial is based on preclinical data on prostate cancer cell lines and tumor biopsy specimens suggesting that lower AR activity was correlated with sensitivity to dasatinib [93]. Additionally, preclinical data with pancreatic xenografts using a k-top scoring pairs classifier method to identify a gene pair predictive of saracatinib sensitivity led to the development of a phase II clinical trial selecting patients with this particular gene pair signature [45]. Other clinical trials are also using microarrays to identify candidate genes that might predict response.

Conclusion

As the oldest known proto-oncogene, Src has been extensively studied and is involved in numerous intracellular processes that are important in cancer growth, progression, motility, invasion, and metastasis. Although Src/Abl inhibitors have found their way to the clinic via Abl inhibition in CML, thus far their activity in solid tumors has been limited. Several Src inhibitors are in phase II/III clinical trials in solid tumor patients, with particular promise noted in castration-resistant prostate cancer. The future likely lies in combination strategies and biomarker-driven studies.

Author Contributions

Manuscript writing: Lauren N. Puls, Matthew Eadens, Wells Messersmith

Final approval of manuscript: Wells Messersmith

References

- 1.Rous P. A sarcoma of the fowl transmissible by an agent separable from the tumors cells. J Exp Med. 1911;13:397–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.13.4.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin H. Quantitative relations between causative virus and cell in the Rous no. 1 chicken sarcoma. Virology. 1955;1:445–473. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(55)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin GS. Rous sarcoma virus: A function required for the maintenance of the transformed state. Nature. 1970;227:1021–1023. doi: 10.1038/2271021a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stehelin D, Varmus HE, Bishop JM, et al. DNA related to the transforming gene(s) of avian sarcoma viruses is present in normal avian DNA. Nature. 1976;260:170–173. doi: 10.1038/260170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stehelin D, Guntaka RV, Varmus HE, et al. Purification of DNA complementary to nucleotide sequences required for neoplastic transformation of fibroblasts by avian sarcoma viruses. J Mol Biol. 1976;101:349–365. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin GS. The road to Src. Oncogene. 2004;23:7910–7917. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeatman TJ. A renaissance for Src. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:470–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolen JB, Brugge JS. Leukocyte protein tyrosine kinases: Potential targets for drug discovery. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:371–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roskoski R., Jr Src protein-tyrosine kinase structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, et al. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haskell MD, Slack JK, Parsons JT, et al. c-Src tyrosine phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor, P190 RhoGAP, and focal adhesion kinase regulates diverse cellular processes. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2425–2440. doi: 10.1021/cr0002341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown MT, Cooper JA. Regulation, substrates, and functions of Src. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:121–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita Y, Krause G, Scheffner M, et al. Hakai, a c-Cbl-like protein, ubiquitinates and induces endocytosis of the E-cadherin complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:222–231. doi: 10.1038/ncb758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamir E, Geiger B. Molecular complexity and dynamics of cell-matrix adhesions. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3583–3590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noritake H, Miyamori H, Goto C, et al. Overexpression of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) in metastatic MDCK cells transformed by v-Src. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:105–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1006596620406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsia DA, Mitra SK, Hauck CR, et al. Differential regulation of cell motility and invasion by FAK. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:753–767. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niu G, Wright KL, Huang M, et al. Constitutive Stat3 activity up-regulates VEGF expression and tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:2000–2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons JT, Parsons SJ. Src family protein tyrosine kinases: Cooperating with growth factor and adhesion signaling pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Courtneidge S, Fumagalli S, Koegl M, et al. The Src family of protein tyrosine kinases: Regulation and functions. Dev Suppl. 1993:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaVallee TM, Prudovsky IA, McMahon GA, et al. Activation of the MAP kinase pathway by FGF-1 correlates with cell proliferation induction while activation of the Src pathway correlates with migration. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1647–1658. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levitzki A. Src as a target for anti-cancer drugs. Anticancer Drug Des. 1996;11:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luttrell DK, Lee A, Lansing TJ, et al. Involvement of pp60c-Src with two major signaling pathways in human breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:83–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahimi N, Hung W, Tremblay E, et al. c-Src kinase activity is required for hepatocyte growth factor-induced motility and anchorage-independent growth of mammary carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33714–33721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tice DA, Biscardi JS, Nickles AL, et al. Mechanism of biological synergy between cellular Src and epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1415–1420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson JE, Kulik G, Jelinek T, et al. Src phosphorylates the insulin-like growth factor type I receptor on the autophosphorylation sites. Requirement for transformation by Src. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31562–31571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarez RH, Kantarjian HM, Cortes JE. The role of Src in solid and hematologic malignancies: Development of new-generation Src inhibitors. Cancer. 2006;107:1918–1929. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao W, Irby R, Coppolla D, et al. Activation of c-Src by receptor tyrosine kinases in human colon cancer cells with high metastatic potential. Oncogene. 1997;15:3083–3090. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maa MC, Leu TH, McCarley DJ, et al. Potentiation of epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated oncogenesis by c-Src: Implications for the etiology of multiple human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6981–1985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xing C, Imagawa W. Altered MAP kinase (ERK1,2) regulation in primary cultures of mammary tumor cells: Elevated basal activity and sustained response to EGF. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1201–1208. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.7.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salh B, Marotta A, Matthewson C, et al. Investigation of the Meh-MAP kinase-Rsk pathway in human breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:731–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:337–358. doi: 10.1023/a:1023772912750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irby RB, Yeatman TJ. Role of Src expression and activation in human cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:5636–5642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolen JB, Veillette A, Schwartz AM, et al. Analysis of pp60c-Src in human colon carcinoma and normal human colon mucosal cells. Oncogene Res. 1987;1:149–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talamonti MS, Roh MS, Curley SA, et al. Increase in activity and level of pp60c-Src in progressive stages of human colorectal cancer. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:53–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI116200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park J, Meisler AI, Cartwright CA. c-Yes tyrosine kinase activity in human colon carcinoma. Oncogene. 1993;8:2627–2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cattan N, Rochet N, Mazeau C, et al. Establishment of two new human bladder carcinoma cell lines, CAL 29 and CAL 185. Comparative study of cell scattering and epithelial to mesenchyme transition induced by growth factors. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1412–1417. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumble S, Omary MB, Cartwright CA, et al. Src activation in malignant and premalignant epithelia of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:348–356. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jankowski J, Coghill G, Hopwood D, et al. Oncogenes and onco-suppressor gene in adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. Gut. 1992;33:1033–1038. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazurenko NN, Kogan EA, Zborovskaya IB, et al. Expression of pp60c-Src in human small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:372–377. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosen N, Bolen JB, Schwartz AM, et al. Analysis of pp60c-Src protein kinase activity in human tumor cell lines and tissues. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13754–13759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobs C, Rubsamen H. Expression of pp60c-Src protein kinase in adult and fetal human tissue: High activities in some sarcomas and mammary carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1696–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan M, Li P, Klos KS, et al. ErbB2 promotes Src synthesis and stability: Novel mechanisms of Src activation that confer breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1858–1867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lutz MP, Esser IB, Flossmann-Kast BB, et al. Overexpression and activation of the tyrosine kinase Src in human pancreatic carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:503–508. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajeshkumar NV, Tan AC, De Oliveira E, et al. Antitumor effects and biomarkers of activity of AZD0530, a Src inhibitor, in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4138–4146. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Messersmith WA, Rajeshkumar NV, Tan AC, et al. Efficacy and pharmacodynamic effects of bosutinib (SKI-606), a Src/Abl inhibitor, in freshly generated human pancreas cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1484–1493. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flossmann-Kast BB, Jehle PM, Hoeflich A, et al. Src stimulates insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I)-dependent cell proliferation by increasing IGF-I receptor number in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3551–3554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2260–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shor AC, Keschman EA, Lee FY, et al. Dasatinib inhibits migration and invasion in diverse human sarcoma cell lines and induces apoptosis in bone sarcoma cells dependent on SRC kinase for survival. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2800–2808. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nam S, Kim D, Cheng JQ, et al. Action of the Src family kinase inhibitor, dasatinib (BMS-354825), on human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9185–9189. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serrels A, Macpherson IR, Evans TR, et al. Identification of potential biomarkers for measuring inhibition of Src kinase activity in colon cancer cells following treatment with dasatinib. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:3014–3022. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson FM, Saigal B, Talpaz M, et al. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) tyrosine kinase inhibitor suppresses invasion and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6924–6932. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsao AS, He D, Saigal B, et al. Inhibition of c-Src expression and activation in malignant pleural mesothelioma tissues leads to apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and decreased migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1962–1972. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song L, Morris M, Bagui T, et al. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) selectively induces apoptosis in lung cancer cells dependent on epidermal growth factor receptor signaling for survival. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5542–5548. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tryfonopoulos D, O'Donovan N, Corkery B, et al. Activity of dasatinib with chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15 suppl) Abstract e14605. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang F, Reeves K, Han X, et al. Identification of candidate molecular markers predicting sensitivity in solid tumors to dasatinib: Rationale for patient selection. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2226–2238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trevino JG, Summy JM, Lesslie DP, et al. Inhibition of Src expression and activity inhibits tumor progression and metastasis of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:962–972. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eustace AJ, Crown J, Clynes M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of dasatinib, a potent Src kinase inhibitor, in melanoma cell lines. J Transl Med. 2008;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Demetri GD, Lo Russo P, MacPherson IR, et al. Phase I dose-escalation and pharmacokinetic study of dasatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6232–6240. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haura EB, Tanvetyanon T, Chiappori A, et al. Phase I/II study of the Src inhibitor dasatinib in combination with erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1387–1394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lieu CH, Wolff RA, Eng C. Phase IB study of the Src inhibitor dasatinib with FOLFOX and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract 3536. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu EY, Wilding G, Posadas E, et al. Phase II study of dasatinib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7421–7428. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Araujo J, Armstrong A, Braud EL, et al. Dasatinib and docetaxel combination treatment for patients with castration-resistant progressive prostate cancer: A phase I/II study (CA180086) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15 suppl) Abstract 5061. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mayer E, Baurain J, Sparano J, et al. Dasatinib in advanced HER2/neu amplified and ER/PR-positive breast cancer: Phase II study CA180088. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15 suppl) Abstract 1011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Algazi AP, Weber JS, Andrews S, et al. A phase I/II trial of DTIC and dasatinib in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract 8532. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson FM, Bekele BN, Feng L, et al. Phase II study of dasatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4609–4615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hiscox S, Morgan L, Green TP, et al. Elevated Src activity promotes cellular invasion and motility in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang YM, Bai L, Liu S, et al. Src family kinase oncogenic potential and pathways in prostate cancer as revealed by AZD0530. Oncogene. 2008;27:6365–6375. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Purnell PR, Mack PC, Tepper CG, et al. The Src inhibitor AZD0530 blocks invasion and may act as a radiosensitizer in lung cancer cells. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:448–454. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819c78fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koppikar P, Choi SH, Egloff AM, et al. Combined inhibition of c-Src and epidermal growth factor receptor abrogates growth and invasion of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4284–4291. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nowak D, Boehrer S, Hochmuth S, et al. Src kinase inhibitors induce apoptosis and mediate cell cycle arrest in lymphoma cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:981–995. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3281721ff6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arcaroli JJ, Touban BM, Tan AC, et al. Gene array and fluorescence in situ hybridization biomarkers of activity of saracatinib (AZD0530), a Src inhibitor, in a preclinical model of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4165–4177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Green TP, Fennell M, Whittaker R, et al. Preclinical anticancer activity of the potent, oral Src inhibitor AZD0530. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:248–261. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baselga J, Cervantes A, Martinelli E, et al. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetics, and inhibition of SRC activity study of saracatinib in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4876–4883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Renouf DJ, Moore MJ, Hedley D, et al. A phase I/II study of the Src inhibitor saracatinib (AZD0530) in combination with gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2010 Dec 18; doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9611-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fury MG, Baxi S, Shen R, et al. Phase II study of saracatinib (AZD0530) for patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) Anticancer Res. 2011;31:249–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mackay HJ, Au HJ, McWhirter E, et al. A phase II trial of the Src kinase inhibitor saracatinib (AZD0530) in patients with metastatic or locally advanced gastric or gastro esophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma: A trial of the PMH phase II consortium. Invest New Drugs. 2011 Mar 12; doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9650-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lara PN, Jr, Longmate J, Evans CP, et al. A phase II trial of the Src-kinase inhibitor AZD0530 in patients with advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer: A California Cancer Consortium study. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:179–184. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328325a867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gajewski T, Zha Y, Clark J. Phase II study of the Src family kinase inhibitor saracatinib (AZD0530) in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9897-4. Abstract 8562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Messersmith WA, Nallapareddy S, Arcaroli J, et al. A phase II trial of saracatinib (AZD0530), an oral Src inhibitor, in previously treated metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl) Abstract e14515. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Traina TA, Sparano JA, Caravelli J, et al. Phase II trial of saracatinib in patients (pts) with ER/PR-negative metastatic breast cancer (MBC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract 1086. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Poole C, Lisyanskaya A, Rodenhuis S, et al. A randomized phase II clinical trial of the Src inhibitor saracatinib (AZD0530) with carboplatin + paclitaxel vs. placebo, carboplatin + paclitaxel in patients with recurrent platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):9720. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jallal H, Valentino ML, Chen G, et al. A Src/Abl kinase inhibitor, SKI-606, blocks breast cancer invasion, growth, and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1580–1588. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coluccia AM, Benati D, Dekhil H, et al. SKI-606 decreases growth and motility of colorectal cancer cells by preventing pp60(c-Src)-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of beta-catenin and its nuclear signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2279–2286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Golas JM, Lucas J, Etienne C, et al. SKI-606, a Src/Abl inhibitor with in vivo activity in colon tumor xenograft models. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5358–5364. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Messersmith WA, Krishnamurthi S, Hewes BA, et al. Bosutinib (SKI-606), a dual Src/Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor: Preliminary results from a phase 1 study in patients with advanced malignant solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18 suppl) Abstract 3552. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gambacorti-Passerini C, Kantarjian H, Baccarani M, et al. Activity and tolerance of bosutinib in patients with AP and BP CML and Ph+ ALL. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl) Abstract 7049. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bruemmendorf TH, Cervantes F, Kim D, et al. Bosutinib is safe and active in patients with chronic phase CML with resistance or intolerance to imatinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl) Abstract 7001. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adjei AA, Cohen R, Kurzrock R, et al. Results of a phase I trial of KX2–391, a novel non-ATP competitive substrate-pocket directed SRC inhibitor, in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15 suppl) doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9929-8. Abstract 3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cortes J, Talpaz M, Bixby D, et al. A phase 1 trial of oral ponatinib (AP24534) in patients with refractory chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and other hematologic malignancies: Emerging safety and clinical response findings. Presented at the American Society of Hematology 2010 Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schweppe RE, Kerege AA, French JD, et al. Inhibition of Src with AZD0530 reveals the Src-Focal Adhesion kinase complex as a novel therapeutic target in papillary and anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2199–2203. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moulder S, Yan K, Huang F, et al. Development of candidate genomic markers to select breast cancer patients for dasatinib therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1120–1127. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mendiratta P, Mostaghel E, Guinney J, et al. Genomic strategy for targeting therapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2022–2029. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morris PG, Chang JC, Abbruzzi A, et al. Correlative biomarkers in a phase II study of dasatinib (D) and weekly (w) paclitaxel (P) for patients (Pts) with metastatic breast carcinoma (MBC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract TPS124. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lu-Emerson C, Norden AD, Drappatz J, et al. Retrospective study of dasatinib in recurrent high-grade glioma (HGG) patients who failed bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl) Abstract e12525. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson FM, Agrawal S, Burris H, et al. Phase 1 pharmacokinetic and drug-interaction study of dasatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer. 2010;116:1582–1591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pusztai L, Moulder SL, Litton JK, et al. Gene-signature-based patient selection for dasatinib therapy in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract TPS130. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tsao AS, Wistuba II, Mehran RJ. Evaluation of Src Tyr419 as a predictive biomarker in a neoadjuvant trial using dasatinib in resectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract 7042. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schuetze S, Wathen K, Choy E, et al. Results of a Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration (SARC) phase II trial of dasatinib in previously treated, high-grade, advanced sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15 suppl) Abstract 10009. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pegram MD, Silva OE, Higgins C, et al. Phase IB pharmacokinetic (PK) study of Src kinase inhibitor AZD0530 plus anastrozole in postmenopausal hormone receptor positive (HR+) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl) Abstract e13074. [Google Scholar]