Myelodysplastic syndrome patient perceptions regarding their disease severity, prognosis, and treatment outcome were assessed using an Internet-based survey, and differences between patients with higher- and lower-risk disease and between those receiving active treatment and supportive care were determined. Patients with MDS were found to have a limited understanding of their disease characteristics, prognosis, and treatment goals.

Keywords: Myelodysplastic syndromes, Health survey, Patient-reported outcomes, Treatment outcome

Abstract

Purpose.

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) are a heterogenous group of clonal hematopoietic disorders affecting approximately 60,000 people in the U.S. Little information is available regarding how aware MDS patients are of their disease severity, prognosis, and treatment outcomes.

Methods.

This Internet-based survey assessed patient perceptions regarding these factors, determined differences between patients with higher- and lower-risk disease and between those receiving active treatment and supportive care, and assessed patient-reported outcomes.

Results.

Among 358 patients (median age, 65 years), the median time since MDS diagnosis was 3 years and time from initial hematologic abnormality detection was 6 years. Many patients (55%) did not know their International Prognostic Scoring System score, 42% were unaware of their blast percentage, and 28% were unaware of their cytogenetics. Patients were unlikely to recall having their MDS described as cancer (7%), 37% felt their treatment would improve survival, and 16% felt treatment would be curative. Patients receiving active treatment were more likely to believe their therapy would prolong survival than those receiving supportive care (52% versus 31%; p < .001) or be curative (23% versus 14%; p = .03). Patients with higher-risk disease were more likely to think their therapy would be curative than those with lower-risk disease (26% versus 11%; p = .01). Patients with MDS reported poor physical or mental health on two to three times more days per month than population norms.

Conclusion.

Patients with MDS have a limited understanding of their disease characteristics, prognosis, and treatment goals. These results may help improve physician–patient communication and identify factors to consider when making treatment decisions.

Introduction

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) comprise a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic disorders that often result in cytopenias and have the potential to evolve to acute myeloid leukemia [1–3]. According to U.S. epidemiologic data, yearly incidence rates of MDS increased from 3.1 per 100,000 in 2001 to 3.8 per 100,000 in 2004, with 10,000–45,000 MDS cases diagnosed annually [4–6]. It is estimated that 60,000 people are living with MDS in the U.S. [7]. Approximately 71% of newly diagnosed patients have lower-risk disease (International Prognostic Scoring System [IPSS] [2] Low or Intermediate [Int]-1), with a median expected survival duration of 3–6 years. The remaining 29% of patients have higher-risk disease (IPSS Int-2 or High), with a median expected survival time <2 years [2].

Most MDS patients receive supportive care (commonly including blood transfusions for symptomatic anemia) or some form of active therapy [8–11]. Rarely, patients undergo potentially curative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Treatment choice depends on the individual's medical characteristics, disease status, potential clinical outcomes, and impact of any intervention on the patient's health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Various aspects of HRQOL in patients with MDS, such as levels of fatigue, have been investigated by conducting patient interviews and Internet-based surveys [12, 13]. Recently published results of face-to-face interviews with MDS patients uncovered a substantial burden associated with transfusions and transfusion dependency [14]. Little information is available regarding the degree to which MDS patients are aware of their disease severity, likely treatment outcome, and prognosis, and the extent to which doctors have communicated this information to them.

We conducted an Internet-based survey to assess patient perceptions regarding their disease, treatment, and prognosis, and whether or not differences in these parameters existed between patients with higher- and lower-risk disease, and in those receiving active treatment versus supportive care.

Methods

Study Design

Patients with MDS registered in the Aplastic Anemia & MDS International Foundation (AAMDSIF) database and who had provided e-mail addresses were invited to participate in an online survey via e-mail invitations containing an embedded link to the survey. The survey remained live for 5 days following the distribution of these e-mail invitations. A second round of e-mail invitations was sent 1 week later to those who did not respond to the first solicitation, and the survey period was extended by an additional week. The survey was conducted over a 2-week period in March 2009.

Inclusion Criteria

All included respondents were required to have a diagnosis of MDS and working knowledge of English, computer proficiency, and Internet access (or have caregiver assistance for these requirements). Responses to questions regarding MDS status were reviewed by one of the investigators (M.A.S.) to verify that self-reported MDS diagnosis information was internally consistent.

Informed Consent

The protocol and consent form were approved by the Copernicus Group Independent Review Board. As an incentive to complete the survey, a U.S. $15 Amazon.com gift card was offered to the first 300 respondents. All survey responders had to provide online informed consent to be eligible for study inclusion.

Questionnaire

The self-assessment survey consisted of 55 questions assessing patient demographics, diagnosis, medical history, therapeutic goals, transfusion burden, disease knowledge, medical evaluation, prognosis, and treatment. Patients were asked to respond to treatment and transfusion questions for therapies received within the previous 3 months, and received ever. Questions were developed based on input from patient advocates, medical oncologists with expertise in MDS, and patients and family members. The survey included open- and closed-ended questions, single-answer and multiple-choice questions, as well as grading scale questions (AAMDSIF Survey, supplemental online data).

The survey was first piloted in six MDS patients in February 2009, and then modified following unstructured 30- to 45-minute interviews, during which pilot responders were asked how they interpreted the meaning of specific questions and how they developed their answers, as well as their impressions of the functionality of the online questionnaire. Technical terms (such as “cytogenetics”) were modified to lay terms (such as “abnormal genes or chromosomes”) to minimize responder confusion.

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) components were assessed using a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HRQOL instrument according to the state-based Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [15]. The core Healthy Days (CDC HRQOL-4) questionnaire assesses a person's perceived sense of well-being through four questions on: (a) self-rated health, (b) the number of recent days when physical health was not good, (c) the number of recent days when mental health was not good, and (d) the number of recent days with activity limitation because of poor physical or mental health [15].

Patient Definitions

Patients were categorized as receiving “active treatment” (including antithymocyte globulin, lenalidomide, azacitidine, decitabine, stem cell transplantation, or enrollment in a clinical trial) or “supportive care” (patients who had not received these treatments) during the 3 months prior to the survey. Higher-risk disease was defined as IPSS Int-2 or High [2]; lower-risk disease was defined as IPSS Low or Int-1. Patients who did not know their IPSS risk were not included in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics, objective medical data, and PROs were analyzed using proportions and medians. Comparisons between patients receiving active treatment and those receiving supportive care, and between patients with higher- and lower-risk disease were calculated using t-tests and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests; relative risks and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from 2 × 2 tables are reported as appropriate. All reported p-values are two-sided.

Results

Survey Participation

Of 3,131 patients invited to participate, 361 (11.5%) completed the survey. This is around the expected rate of response for an Internet-based survey in adults [16]. Because pediatric MDS differs in a number of ways from adult MDS, three patients aged <19 years were eliminated from this analysis, leaving 358 surveys: 296 completed following the first e-mail invitation and 62 completed after the second invitation. Patients from 47 U.S. states participated.

Baseline Characteristics of Respondents

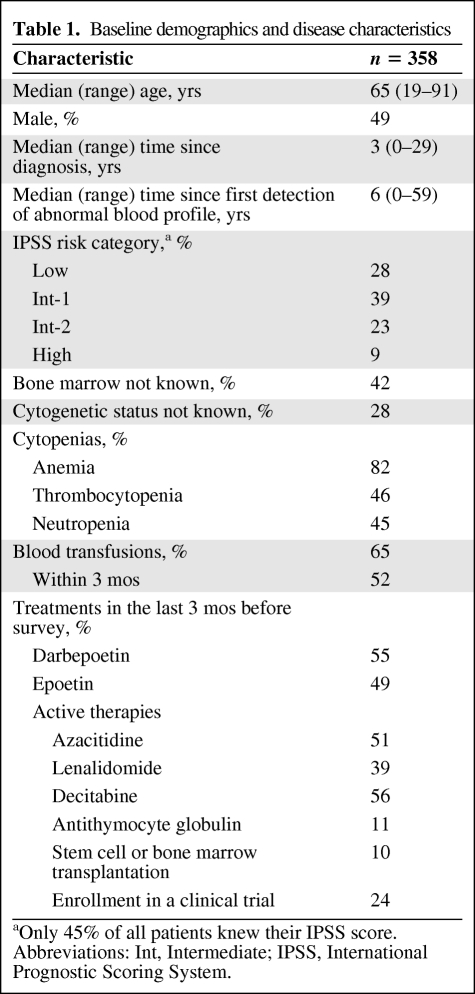

Included survey responders had a median age of 65 years (range, 19–91 years); 51% were women (Table 1). Respondents were diagnosed with MDS a median of 3 years prior to participation in this survey (range, 0–29 years), whereas an abnormal hematologic finding was first detected on peripheral blood counts a median of 6 years prior to the survey (range, 0–59 years). Of the 45% of patients who knew their IPSS score, 67% had lower-risk MDS and 33% had higher-risk disease.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

aOnly 45% of all patients knew their IPSS score.

Abbreviations: Int, Intermediate; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System.

Most patients (73%) received growth factors (including erythropoiesis-stimulating agents [ESAs]) or supportive care, whereas 27% received active treatment. Therapies during the 3 months prior to the survey are shown in Table 1. Nearly one quarter (24%) of the patients had been involved in a clinical trial during the 3 months before taking the survey.

Patient Disease Awareness

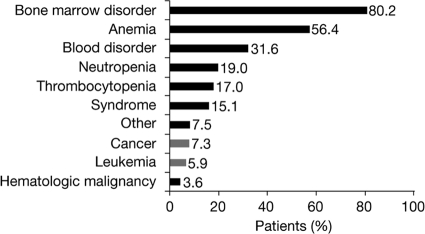

Patients reported that MDS was first described to them as a bone marrow disorder (80%), anemia (56%), blood disorder (32%), neutropenia (19%), thrombocytopenia (17%), or a syndrome (15%), but rarely as cancer (7%) or leukemia (6%) (Fig. 1). In this part of the survey, patients could provide more than one response. Most respondents (55%) did not know their IPSS risk score or category, 42% did not know their bone marrow blast percentage, and 28% did not know their cytogenetic status (Table 1).

Figure 1.

How myelodysplastic syndrome was first described to patients.

Note that patients could select more than one answer. Because multiple answers per participant were possible, the percentages exceed 100%.

Burden of Blood Transfusions in MDS

Of 234 patients (65% of total respondents) who had received a blood transfusion, 121 (52%) had received one within the past 3 months; 96 (27%) were receiving blood transfusions at the time the survey was conducted, of whom 62 (65%) had been receiving blood transfusions for ≥1 year, and 59 (61%) were receiving transfusions at least once per month. Among patients who had blood transfusions, 34% felt that the transfusions were a burden to their family, whereas 65% responded that they would undergo a drug treatment that would temporarily make them feel worse if it would enable them to stop or reduce blood transfusions.

Understanding and Discussion of Prognosis

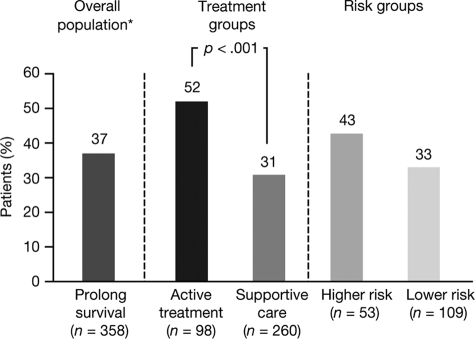

Patients' understanding of treatment goals and prognosis was generally poor. Overall, 37% of patients felt that their most current treatment would increase their chances of survival (including 26% who felt their therapy had a >50% chance of improving their survival), whereas 36% were uncertain about how their treatment would affect their prognosis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients who believed their most current treatment would prolong survival, in the overall population and according to treatment group and risk group.

*36% were uncertain and 27% did not believe that treatment would prolong survival.

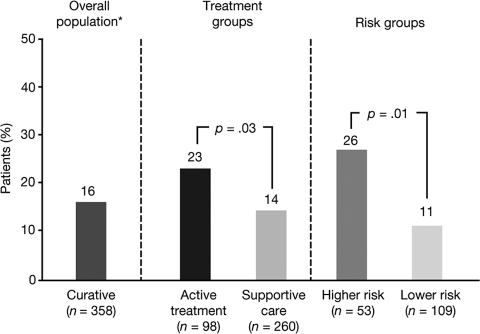

Sixteen percent of survey participants agreed that their most current treatment could be curative (including 10% who thought there was a >50% chance of cure), whereas 30% were uncertain (Fig. 3). Many patients (35%) had not discussed with their physician the potential impact of their most current treatment on survival or the risk for leukemic evolution.

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients who believed their most current treatment would be curative, in the overall population and according to treatment group and risk group.

*30% were uncertain and 54% did not believe that treatment would be curative.

Goals of Therapy

In the overall population, the main goals of treatment were considered to be to stop or slow the progression of MDS (60%), increase life expectancy (48%), improve overall quality of life (36%), and relieve fatigue (34%).

Comparative Analysis: Active Treatment Versus Supportive Care

When comparing patients undergoing active treatment (n = 98) with those on supportive care (n = 260), there were no significant differences in how MDS was first described and in the percentage of patients who knew their IPSS score. More men than women were on active treatment (35% versus 20%; relative risk [RR], 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.5; p < .002). As expected, patients on active treatment were twice as likely to be currently receiving transfusions than patients on supportive care (RR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.5–2.8; p < .001). Among patients who knew their IPSS score, a higher proportion of higher-risk patients were on active treatment than lower-risk patients (47% versus 27%; p < .01). Patients on active treatment were more likely to discuss prognosis with their physician than those receiving supportive care (73% versus 61%; p = .03) and were more likely to be aware of their blast count (67% versus 55%; p = .05). Patients on active treatment were also more likely to believe that their most current treatment would prolong survival (52% versus 31%; p < .001) (Fig. 2) or be curative (23% versus 14%; p = .03) (Fig. 3).

Considering the main goals selected for MDS treatment, the proportion of patients who selected “to stop/slow MDS progression” was significantly higher in the active treatment group than in the supportive care group (80% versus 53%; p ≤ .001). Also, more participants in the active treatment group than in the supportive care group selected “for increased life expectancy” as their treatment goal (60% versus 43%; p = .005).

Significantly more active treatment patients than supportive care patients preferred their most current treatment because they agreed that “it treated their disease, not just the symptoms” (60% versus 31%; p < .001) and that “their most current treatment gave them a more positive outlook on the future” (67% versus 45%; p < .001). More patients receiving active treatment were currently being treated with blood transfusions than those only receiving supportive care (43% versus 21%). Significantly more patients on active treatment said they would undergo drug treatment that temporarily made them feel worse if it would enable them to stop or reduce blood transfusions, compared with patients receiving supportive care (36% versus 10%; p < .001).

Comparative Analysis: Impact of IPSS Risk

Among the 45% of patients who knew their IPSS risk, there were no significant differences between patients with higher- and lower-risk MDS in knowledge of blast percentages and treatments received, or perception of therapeutic goals. Compared with patients with lower-risk disease, those with higher-risk disease were more likely to think that their most current treatment would prolong survival (43% versus 33%; p = .20) (Fig. 2) or be curative (26% versus 11%; p = .01) (Fig. 3); only four patients had undergone stem cell or bone marrow transplantation within 3 months of the survey. Patients with higher-risk disease had undergone significantly more bone marrow biopsies over the course of their lifetime than those with lower-risk disease (mean [standard deviation], 5.2 [6.1] versus 2.8 [2.2]; p < .002).

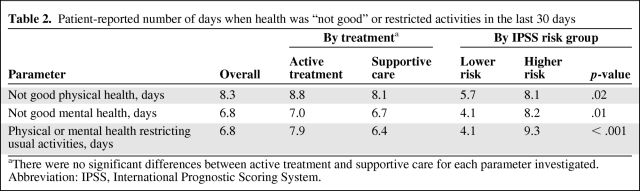

Comparative Analysis: PROs

For all patients, the mean number of days in the past 30 days described as “not good mental health,” “not good physical health,” or “activity limitations” in the PRO assessment were 6.8, 8.3, and 6.8, respectively. Significantly more patients with ≥4 days of “activity limitation” classified their general health as “fair/poor,” compared with those with <4 days (54% versus 19%; p < .001). Patients receiving active treatment or supportive care had similar PROs, measured as the number of days that mental or physical health was “not good” or with “activity limitations” (Table 2). Patients with higher-risk MDS had significantly worse PRO outcomes than lower-risk patients (mean number of days in the past 30 days described as “not good physical health,” 8.1 versus 5.7; p = .02; “not good mental health,” 8.2 versus 4.1; p = .01; “activity limitations,” 9.3 versus 4.1; p < .001).

Table 2.

Patient-reported number of days when health was “not good” or restricted activities in the last 30 days

aThere were no significant differences between active treatment and supportive care for each parameter investigated.

Abbreviation: IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System.

Discussion

With evolving epidemiologic data, such as the publication of U.S. MDS incidence rates within the past 3 years [4, 5], we are only just beginning to understand the societal impact of MDS within the U.S. Population data, although useful for assessing gross patterns, by design cannot elucidate patient-oriented disease information, particularly understanding of disease severity and its implications.

This is one of the largest Internet-based surveys of MDS patients ever conducted, including 358 responders (11.4%), a response rate considered typical of an online survey [16]. Patients were representative in their distribution of baseline characteristics and disease severity in that they tended to be transfusion dependent [10, 11], were more likely to have lower- rather than higher-risk disease [8, 10], and had been treated with ESAs or disease-modifying therapies [8]. Patients had been living with their disease for a median of 3 years, and for the first time, we report the median time by which a first finding of abnormal blood counts preceded an MDS diagnosis in a U.S. population—an additional 3 years. Our findings suggest that most patients who completed this survey have only a limited understanding of the basic characteristics of their disease and of key markers for disease severity and prognosis, such as IPSS score, blast percentage, and karyotype. Few patients had MDS described to them as a cancer or leukemia. Many patients, even some receiving supportive care, believed that their most current treatment would prolong their survival or even be curative, despite only one active therapy (azacitidine) having demonstrated a survival advantage in a randomized clinical trial [17] and despite only stem cell transplantation being potentially curative. This is understandable, because from a patient's perspective, it is only natural to conclude that receiving blood and platelet transfusions, or preventing the need for those transfusions with ESAs, would prolong life [18, 19].

These results are consistent with other phase I studies showing discordance between high patient expectations and physician beliefs, and even greater optimism among patients undergoing treatment [20, 21]. This study did not enable us to make a distinction between a patient's belief—initiated by the patient themselves—and a belief from a treating physician. A natural corollary to this point is the “power of positive thinking.” Certainly, patients may overestimate their conclusions about the possible benefits of a therapy in the belief that negative thoughts may worsen their disease course. One study in breast cancer patients showed that optimism had beneficial effects on patient quality of life [22].

For this cohort, MDS had a clear impact on PROs, compared with the age-matched general population. Two previous surveys investigated PROs in patients with MDS, and results from these suggest that hemoglobin levels and fatigue seem to have the most impact on PROs [12, 13]. In agreement with our findings, a health utility assessment study found that achieving transfusion independence was highly valued by patients with MDS [14]. Patients completing this survey (median age, 65 years) tended to be younger than that reported in population studies (72–77 years) [5, 8, 23]. This may have impacted the generalizability of PRO outcomes presented in this study.

The number of days per month when patients completing the online survey reported “not good mental health,” “not good physical health,” or “activity limitations” (6.8, 8.3, and 6.8, respectively) was much higher for the respondents in our survey (median age, 65 years) than previously published U.S. population norms in patients aged ≥65 years (1.7–1.9 days, 4.8–5.9 days, and 2.0–3.0 days, respectively) [15]. This finding reinforces the serious impact of MDS on PROs.

Focusing on comparisons of patient groups, those with higher-risk disease reported significantly more mental and physical health days compromised than patients with lower-risk disease, as might be expected with progressive cytopenias or with side effects from active therapies. PROs may have been worse among higher-risk patients because of disease-related symptoms that were not captured in the survey, or because these patients had knowledge that their disease had a poor prognosis. Patients receiving active treatment were also more likely to have their prognosis discussed, to be more positive about their treatment outcome, and to be more focused on modifying their disease than those receiving supportive care, as might be expected from an engaged informed consent process prior to the administration of active therapy. This is the first study to quantify PRO differences among MDS subgroups of different disease severity.

One limitation of this study is its inherent reliance on self-reported data, with no opportunity to independently confirm participants' reports of their disease history and treatment. Another is the potential for response bias in the population who elected to complete the survey. Patients who had the wherewithal and performance status to take the time to check their e-mail, follow a link to the Internet, and complete an online survey may have been less impaired than the general MDS population. These potential shortcomings are inherent in any study that relies on patients who volunteer information, particularly with respect to PROs. Patients who participated in this study were registered with AAMDSIF, had access to e-mail communications, and had the ability to navigate an Internet-based survey. Thus, the lack of patient knowledge about disease status was particularly surprising given the patient population studied, because these patients were registered with AAMDSIF, and thus by definition had access to patient information regarding their disease, treatment options, and therapy outcomes. Given their facility with the Internet, these patients might have been more likely to have access to MDS information and may not be representative of the entire MDS population. Considering these limitations, the information gap evident in our survey is even more striking, because a general MDS population, with a lower level of access to information on the Internet or access to patient organizations such as AAMDIF, would be even less knowledgeable about their disease. Further improvements in communication between physicians and their patients are required to increase patient understanding of MDS. For example, patients may not remember their exact IPSS score, but if IPSS is used during physician–patient discussions regarding prognosis and treatment choices, patients may recall the context.

Summary

Results from our study demonstrate that selected patients with MDS who completed an online survey had a limited understanding of their disease and the therapeutic goals for the treatment options available to them. This may be improved by clear presentation of prognostic information and active patient engagement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Access to the patient survey by the AAMDS Foundation and the data collection and data entry by RedCar were funded by Celgene.

First presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in New Orleans, Louisiana on December 5, 2009: Sekeres MA, Maciejewski JP, List AF et al. Perceptions of disease state, treatment expectations, and prognosis among patients with myelodysplastic syndromes [abstract]. Blood 2009;114:Abstract 1771.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Mikkael A. Sekeres, Paul Scribner, John Huber

Provision of study material or patients: Mikkael A. Sekeres, Paul Scribner, Alan F. List, John Huber, David P. Steensma, Richard Stone, Andrew Artz, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski

Collection and/or assembly of data: Mikkael A. Sekeres, Paul Scribner, Alan F. List, John Huber, David P. Steensma, Richard Stone, Andrew Artz, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski

Data analysis and interpretation: Mikkael A. Sekeres, Paul Scribner, Alan F. List, John Huber, David P. Steensma, Richard Stone, Andrew Artz, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski, Arlene S. Swern

Manuscript writing: Mikkael A. Sekeres, Paul Scribner, John Huber

Final approval of manuscript: Mikkael A. Sekeres, Paul Scribner, Alan F. List, John Huber, David P. Steensma, Richard Stone, Andrew Artz, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski, Arlene S. Swern

The authors take full responsibility for the content of the paper but thank Nikki Moreland and Catalin Topala, Ph.D. (Excerpta Medica, supported by Celgene), for their assistance in copyediting and drawing of figures.

References

- 1.Kantarjian H, Giles F, List A, et al. The incidence and impact of thrombocytopenia in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer. 2007;109:1705–1714. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malcovati L, Germing U, Kuendgen A, et al. Time-dependent prognostic scoring system for predicting survival and leukemic evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3503–3510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rollison DE, Howlader N, Smith MT, et al. Epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myeloproliferative disorders in the United States, 2001–2004, using data from the NAACCR and SEER programs. Blood. 2008;112:45–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X, Does M, Raza A, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes: Incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007;109:1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg SL, Chen E, Corral M, et al. Incidence and clinical complications of myelodysplastic syndromes among United States Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2847–2852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekeres MA. The epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekeres MA, Schoonen WM, Kantarjian H, et al. Characteristics of US patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: Results of six cross-sectional physician surveys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1542–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.List A, Kurtin S, Roe DJ, et al. Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:549–557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: A study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarjian H, Issa JP, Rosenfeld CS, et al. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes: Results of a phase III randomized study. Cancer. 2006;106:1794–1803. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansen AJ, Essink-Bot ML, Beckers EA, et al. Quality of life measurement in patients with transfusion-dependent myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:270–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steensma DP, Heptinstall KV, Johnson VM, et al. Common troublesome symptoms and their impact on quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): Results of a large internet-based survey. Leuk Res. 2008;32:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szende A, Schaefer C, Goss TF, et al. Valuation of transfusion-free living in MDS: Results of health utility interviews with patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:81. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. [accessed May 28, 2010]. Measuring Healthy Days. Population Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/pdfs/mhd.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kongsved SM, Basnov M, Holm-Christensen K, et al. Response rate and completeness of questionnaires: A randomized study of internet versus paper-and-pencil versions. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e25. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.3.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: A randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jädersten M, Montgomery SM, Dybedal I, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment of anemia in MDS with erythropoietin and G-CSF. Blood. 2005;106:803–811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golshayan AR, Jin T, Maciejewski J, et al. Efficacy of growth factors compared to other therapies for low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackillop WJ, Stewart WE, Ginsburg AD, et al. Cancer patients' per-ceptions of their disease and its treatment. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:355–358. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, et al. Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: Implications for physician-patient communication. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2589–2596. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SK, Herndon JE, Lyerly HK, et al. Correlates of quality of life-related outcomes in breast cancer patients participating in the Pathfinders pilot study. Psychooncology. 2010 May 26; doi: 10.1002/pon.1770. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1002/pon.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phekoo KJ, Richards MA, Ml̸ler H, et al. South Thames Haematology Specialist Committee. The incidence and outcome of myeloid malignancies in 2,112 adult patients in southeast England. Haematologica. 2006;91:1400–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.