Abstract

Rationale

In human and animal studies, adolescence marks a period of increased vulnerability to the initiation and subsequent abuse of drugs. Adolescents may be especially vulnerable to relapse, and a critical aspect of drug abuse is that it is a chronically relapsing disorder. However, little is known of how vulnerability factors such as adolescence are related to conditions that induce relapse, triggered by the drug itself, drug-associated cues, or stress.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to compare adolescent and adult rats on drug-, cue-, and stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior.

Methods

On postnatal days 23 (adolescents) and 90 (adults), rats were implanted with intravenous catheters and trained to lever press for i.v. infusions of cocaine (0.4 mg/kg) during two daily 2-h sessions. The rats then self-administered i.v. cocaine for ten additional sessions. Subsequently, visual and auditory stimuli that signaled drug delivery were unplugged, and rats were allowed to extinguish lever pressing for 20 sessions. Rats were then tested on cocaine-, cue-, and yohimbine (stress)-induced cocaine seeking using a within-subject multicomponent reinstatement procedure.

Results

Results indicated that adolescents had heightened cocaine seeking during maintenance and extinction compared to adults. During reinstatement, adolescents (vs adults) responded more following cocaine- and yohimbine injections, while adults (vs adolescents) showed greater responding following presentations of drug-associated cues.

Conclusion

These results demonstrated that adolescents and adults differed across several measures of drug-seeking behavior, and adolescents may be especially vulnerable to relapse precipitated by drugs and stress.

Keywords: Adolescents, Cocaine, Rats, Reinstatement, Stress, Cues

Introduction

In humans, adolescence marks a period of important physiological and emotional change that is involved in healthy development (Ernst et al. 2006). However, adolescence is also characterized by increased susceptibility to disorders related to deficits in conduct (Fontaine 2006), inhibitory control (Spencer et al. 2007), and stress reactivity (Spear 2009), all of which are vulnerability factors in the development of adolescent drug addiction (Gullo and Dawe 2008; for reviews, see Deas 2006; Ivanov et al. 2008; Laviola et al. 1999). Indeed, adolescents are more likely than adults to initiate and maintain (Winters and Lee 2008) drug use, and once addicted they more readily engage in potentially lethal binge-like patterns of drug intake (Baumeister and Tossmann 2005; Estroff et al. 1989; McCambridge and Strang 2005). Relapse potential is also increased in adolescents (Brown and D'Amico 2001; Catalano et al. 1990; Chung and Maisto 2006), and adolescents are more resistant to drug abuse treatment interventions (Dennis et al. 2004; Perepletchikova et al. 2008; Winters et al. 2000). Longitudinal studies have further confirmed the dangers of adolescent drug use and indicate that the earlier drug use is initiated, the more likely that an individual will have life-long problems with drug addiction (Baumeister and Tossmann 2005; Palmer et al. 2009). Offspring of individuals addicted to drugs are even more likely to develop substance abuse disorders (Courtois et al. 2007; Hoffmann and Cerbone 2002; Obot et al. 2001), thus perpetuating a cycle of drug abuse that may span generations.

Animal models provide a controlled and systematic approach to the study of the effects of age on drug abuse, and they allow adolescents and adults to be compared across several behavioral parameters. One particular parameter is drug-induced locomotor activity, a measure of drug sensitivity. Subjects that exhibit heightened locomotor activity are thought to be more sensitive to the effects of drugs than those with less activity. Stimulants such as cocaine produce greater increases in locomotor behavior in early adolescent compared to older rodents (Badanich et al. 2008; Catlow and Kirstein 2007; Maldonado and Kirstein 2005a, b; Niculescu et al. 2005). However, results with other drugs such as nicotine and alcohol are less consistent (Schramm-Sapyta et al. 2009).

Adolescent and adult rodents also differ in their response to aversive and rewarding/reinforcing effects of drugs. For example, adolescent rodents are less sensitive to the aversive effects of drugs of abuse including nicotine, ethanol, and cocaine (Schramm-Sapyta et al. 2009). In contrast, other studies have shown that adolescents are more sensitive to the rewarding effects of cocaine and nicotine as measured by the conditioned place preference paradigm (Badanich et al. 2006; Brenhouse and Andersen 2008; Brenhouse et al. 2008; Brielmaier et al. 2007; Kota et al. 2007; Shram et al. 2006; Torres et al. 2008; Zakharova et al. 2009a, b). Thus, adolescents, compared to adults, are less sensitive to the aversive effects of drugs of abuse and more amenable to their rewarding effects and these factors may converge to increase drug abuse vulnerability.

In addition to enhanced rewarding effects, results indicate that the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse are greater in adolescents than adults. Adolescents self-administer greater amounts of amphetamine, nicotine, and ethanol compared to adults (Chen et al. 2007; Fullgrabe et al. 2007; Levin et al. 2003, 2007; Shahbazi et al. 2008; Vetter et al. 2007). Results with cocaine are less consistent, with a majority of studies indicating no link between adolescence and heightened cocaine self-administration (Belluzzi et al. 2005; Frantz et al. 2007; Kantak et al. 2007; Kerstetter and Kantak 2007; Li and Frantz 2009; Perry et al. 2007). However, several of these studies have focused on acquisition (Frantz et al. 2007; Perry et al. 2007) or behavior maintained under limited access conditions (2 h/day; Frantz et al. 2007; Kantak et al. 2007; Kerstetter and Kantak 2007; Li and Frantz 2009) and/or with large doses of cocaine (Kantak et al. 2007; Kerstetter and Kantak 2007). These factors have been shown to be insensitive to group differences (Carroll et al. 2008; Lynch and Carroll 1999; Roth et al. 2004). In addition, no studies have compared adults and adolescents on other measures of drug seeking or during other phases of the drug abuse process such as extinction and reinstatement. Little is also known about how factors such as stress, cues, and drugs interact with age to influence drug seeking. Previous work indicates that stress and environmental stimuli increase vulnerability to relapse in human adolescent drug abusers (Chung and Maisto 2006; Lopez et al. 2005; Rao et al. 1999). The purpose of the present study was to compare adolescent and adult rats on the maintenance, extinction, and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. A multicomponent reinstatement procedure was used to examine the effects of drug, cues, and stress priming conditions on reinstatement of cocaine seeking in adolescent and adult male rats.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Fourteen adult (postnatal (PN) day90) and 15 adolescent (PN day23) male Wistar rats served as subjects in the present study. Rats were bred at the University of Minnesota from parents obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA and housed in temperature- (24°C) and humidity-controlled holding rooms under a constant light/dark cycle (12:12 h with room lights on at 6:00 a.m.) where they had ad libitum access to food and water. Adult male rats weighed 450–500 g at the beginning of the study, and adolescent rats weighed 70–90 g. Male rats are considered adults on PN day60 (Ojeda et al. 1980; Spear 2000a, b); thus, adolescence was defined as PN days21 to 60. There were seven rats in the adolescent group that reached adulthood (PN day60) during the end of the extinction phase and were not included in the reinstatement portion of the study. During experimental sessions, adolescent and adult rats had free access to water and were given 20 g ground food (Purina Laboratory Chow) at the end of each session (3:00 p.m.). The experimental protocol (0708A15263) was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and the experiment was conducted in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (National Research Council 2003) in laboratory facilities accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Apparatus

Custom-made operant conditioning chambers were used in the present study as previously described in detail (Carroll et al. 2002). Briefly, chambers were octagonal in shape and consisted of two response levers (one active and one inactive), two sets of stimulus lights, a house light, and two steel panels that allowed for the insertion of a food jar and a water bottle. Operant conditioning chambers were enclosed in melamine-coated sound-attenuating wooden boxes equipped with a ventilation fan that supplied noise to mask acoustic disturbances. A 35-ml syringe pump (model PHM-100, MedAssociates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA) was located on the inside of the wooden enclosure and delivered response contingent i.v. cocaine during experimental sessions.

Drugs

Cocaine HCl was supplied by National Institute of Drug Abuse (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA), dissolved in 0.9% NaCl at a concentration of 1.6 mg cocaine HCl/1 ml saline, and refrigerated. Heparin (1/200 ml saline) was added to the cocaine solution to prevent catheter occlusion from thrombin buildup. The flow rate of each cocaine infusion was 0.025 ml/s, and the duration of pump activation (1 s/100 g of body weight) was adjusted to maintain rats at a 0.4-mg/kg cocaine dose throughout self-administration testing. Due to the rapid weight gain in the adolescent group, the infusion duration was adjusted approximately every 3 days to maintain the 0.4-mg/kg cocaine dose.

Procedure

Surgical procedure

On PN days 23–25 for adolescents and 90–100 for adults, rats were implanted with an intravenous catheter following the procedure outlined by Carroll and Boe (1982). Rats were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) and administered doxapram (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and atropine (0.4 mg/ml, 0.15 ml, s.c.) to facilitate respiration under anesthesia. An incision was made lateral to the trachea, the right jugular vein was exposed, and a small incision was made perpendicular to the vein. The beveled end of a polyurethane catheter (MRE-040, Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA, USA) was inserted and then secured to the vein with silk sutures. The free end of the catheter was guided subcutaneously to the midscapular region of the neck where it exited via a small incision and attached to a metal cannula that was embedded in the center of the rat's soft plastic covance-infusion harness (C3236, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA). Following the surgical procedure, rats were allowed a 3-day recovery period during which antibiotic and analgesia were administered following guidelines outlined by the University of Minnesota IACUC. After the recovery period, catheters were flushed with a heparinized saline solution at 8:00 a.m. daily to prevent catheter blockage, and every 3 days weights were taken at 3:00 p.m. Catheter patency was checked every 7 days by injecting a 0.1-ml solution containing ketamine (60 mg/kg), midazolam (3 mg/kg), and saline. If a loss of the righting reflex was not manifest upon a catheter patency check, a second catheter was implanted in the left jugular vein following the methods described above. Three rats in the adult group received a second catheter.

Acquisition of cocaine self-administration

The experimental procedure is shown in Table 1. Three days following surgery, rats were trained to self-administer 0.4-mg/kg i.v. cocaine under a fixed ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement. Training sessions began at 9:00 a.m. with the illumination of the house light and ended at 3:00 p.m. with its termination. During each self-administration session, a response on the left lever (active lever) delivered a single infusion of 0.4-mg/kg cocaine and activated the set of stimulus lights located above the lever for the duration of the infusion. A response on the right lever (inactive lever) also illuminated the stimulus lights above that lever but did not produce i.v. infusions of cocaine. To facilitate drug self-administration during training, rats received three experimenter delivered i.v. infusions at 9:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., and again at 1:00 p.m. Levers were also baited with a small amount of peanut butter at each time point until rats reached 60 infusions, and they were then allowed to continue self-administering cocaine. Acquisition of cocaine self-administration occurred once rats earned at least 60 unassisted infusions with a 2:1 active/inactive lever response ratio.

Table 1.

Experimental procedure

| Phase | Acquisition | Maintenance | Extinction | Reinstatement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Cue | YOH | ||||||

| S/D | D/S | S/D | Cue/No Cue | Sal/YOH | ||||

| Days | ∼10 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Session | 6 h | 2, 2 h daily sessions | ||||||

| 9 a.m.–3 p.m. | 9 a.m.–11 a.m. and 1 p.m.–3 p.m. | |||||||

Each block denotes a different condition of the study. Rats were initially trained to lever press for i.v. infusion of cocaine (0.4 mg/kg) during daily 6-h sessions. Subsequently, rats were allowed to self-administer cocaine during two 2-h sessions from 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and again from 1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m. each day for approximately 5 days. Cocaine and cues previously associated with drug self-administration were then removed for 10 days during the extinction condition. Rats were then tested using a multicomponent reinstatement procedure following the administration of cocaine, yohimbine, or the presentation of response contingent cues

Maintenance

Due to the brief duration of adolescence in rats and the goal of comparing adolescents and adults on reinstatement, an abbreviated reinstatement procedure was used. Following acquisition, rats were allowed to maintain stable cocaine intake under experimental conditions identical to those described for training with the exception that self-administration took place during two daily 2-h sessions (9:00 a.m.–11:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m.–3:00 p.m.) that were separated by a 2-h intersession period (11:00 a.m.–1:00 p.m.). Rats self-administered cocaine under this condition for ten sessions (approximately 5 days). Pilot work with this procedure indicated that each session produced stable levels of cocaine intake similar to levels achieved during single daily 2-h sessions.

Extinction and reinstatement

Rats were tested using a multicomponent reinstatement procedure similar to that used by Bongiovanni and See (2008). Following the final day of maintenance, the stimulus lights, house light, and pump were unplugged, and rats were allowed to extinguish lever pressing for 20 additional sessions (10 days). Thus, lever presses during extinction did not result in infusions or the activation of stimulus lights and the house light remained off. This was done to test responding to visual (stimulus lights and house light) and auditory (pump) cues during the subsequent reinstatement condition. During this condition, reinstatement responding was assessed following cocaine, yohimbine, and cue primes during two daily 2-h a.m. and p.m. sessions. Control and priming conditions occurred in counterbalanced order across the 5-day reinstatement procedure to control for possible biases in reinstatement responding during either the a.m. or p.m. sessions (see Table 1). All priming injections occurred immediately before the 9:00 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. sessions.

The first component of the reinstatement procedure consisted of three randomly selected priming doses of cocaine (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg, i.p.), each administered on separate days in counterbalanced order. Each dose of cocaine was administered once during the a.m. or p.m. session and was either preceded or followed by a control session in which a saline i.p. injection was given. During the second component, cue exposure was accomplished by plugging in the house light, stimulus lights (active and inactive levers), and pump during the a.m. session, and rats were tested on reinstatement responding. The house light remained on for the duration of the session and responding during this time activated the pump/stimulus light complex. The house light, stimulus lights (active and inactive levers), and pump were then unplugged during the p.m. session and the rest of the study. During the third component, a saline i.p. injection was administered at the beginning of the a.m. session, while a yohimbine (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) priming injection was administered at the beginning of the following p.m. session. Yohimbine at this dose is considered a pharmacological stressor and has previously been shown to reliably reinstate cocaine-seeking behavior (Feltenstein and See 2006).

Data analysis

The primary dependent measures were active and inactive lever responses and infusions. For the maintenance and extinction phases, measures were averaged across two blocks of sessions and analyzed with a two-factor repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with group as the between-subjects factor and session block as the repeated factor. A two-factor repeated measures ANOVA with group as the between-subjects factor and priming condition as the repeated factor was used to compare groups during reinstatement. Separate two-factor repeated measures ANOVA were used to compare groups on the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in addition to food intake and weight at the beginning and end of the experimental procedure. Post hoc tests were conducted using Fisher's least significant difference protected t tests. All data analyses were conducted using GB Stat (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA).

Results

Table 2 shows the average number of days to reach the acquisition criteria in addition to the mean age, food intake, and weight at the start (first day of self-administration training) and the end of the experimental procedure in adolescent and adult rats. All of the rats in both groups met the acquisition criteria. Also, there were no significant group differences in the number of days required for rats to reach the acquisition criteria, and groups did not differ in the number of infusions during the acquisition condition. However, adults consumed more food than adolescents at the beginning and end of the study (F1, 57=5.71, p<0.05). Examination of weights indicated that adolescent rats significantly increased weight from the beginning of the procedure compared to the end (p<0.01) while adult rats showed a significant decrease (p<0.01). The increase in adolescent weight and decrease in adult weight were likely due to rats being restricted to 20 g of food daily. Throughout the procedure, adolescents consumed approximately 18 g of food daily, while adults consumed all of their food allotment indicating that adolescent rats were food satiated while adults may have been slightly food restricted. Adolescents consumed 0.45, 0.36, and 0.34 kcal, and adults consumed 0.21, 0.22, and 0.21 kcal of food per gram of body weight during the maintenance, extinction, and reinstatement phases, respectively. A two-factor repeated measures ANOVA indicated that adolescents consumed significantly more kilocalories of food per gram body weight than adults across all phases of the study (F1, 83=21.50, p<0.01).

Table 2.

The average number of days to reach the acquisition criteria and mean age, food intake, and weight at the start and end of the experimental procedure

| Beginning of study (day 1) | End of study (approximately day 28) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent | Adult | Adolescent | Adult | |

| Acquisition (days ±SEM) | 9.1 (1.31) | 10.8 (2.37) | – | – |

| Age (days±SEM) | 32.1 (0.97) | 85.6 (5.7) | 57.6 (0.71) | 119.9 (7.1) |

| Food intake (g±SEM) | 17.5 (0.66) | 19.4 (0.48)a | 18.3 (0.89) | 20.0 (0.1)a |

| Weight (g±SEM) | 115.4 (13.7) | 415.6 (15.6) | 221.3 (10.2)b | 363.6 (12.1)c |

Adolescents, compared to adults, consumed significantly less food at the beginning (day 1) and end (day 28) of the study compared to adults (p<0.05)

Adolescents weighed significantly more at the end (day∼28) of the study compared to the beginning (day 1; p<0.05)

Adults weighed significantly less at the end of the study (day∼28) compared to the beginning (day 1; p<0.05)

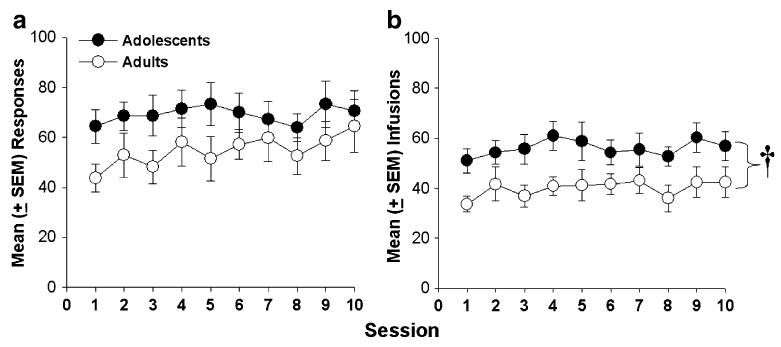

Maintenance

Mean number of active lever responses and infusions earned during the maintenance phase are depicted in Fig. 1. Groups did not differ in responding across session blocks during this phase (Fig. 1a); however, adolescent rats earned significantly more cocaine infusions than adults across the session blocks(F1,57=10.72, p<0.01; Fig. 1b). Analysis of inactive lever pressing indicated that adolescent rats responded significantly more on the inactive lever compared to adults (F1, 57=8.72, p<0.01) and that inactive lever pressing was significantly greater during the second half of maintenance (sessions 6–10) compared to the first half (sessions 1–5) in both groups (F1, 57=6.00, p<0.05). An additional analysis was conducted to determine if heightened cocaine intake in adolescent rats (vs adults) was a result of cocaine-seeking behavior and not due to general activity. Results confirmed that adolescents responded significantly more on the cocaine-paired lever relative to the inactive lever (F1, 57=60.88, p<0.001) verifying that the age differences in cocaine intake were not due to heightened indiscriminate responding in adolescents.

Fig. 1.

Mean (± SEM) responses on the drug-paired lever (a) and cocaine (0.4 mg/kg, i.v.) infusions (b) during ten 2-h sessions under the maintenance condition in adolescent (n=14) and adult (n=15) male rats. Adolescent rats earned significantly more infusions than adult rats over the 5 days (†p<0.05)

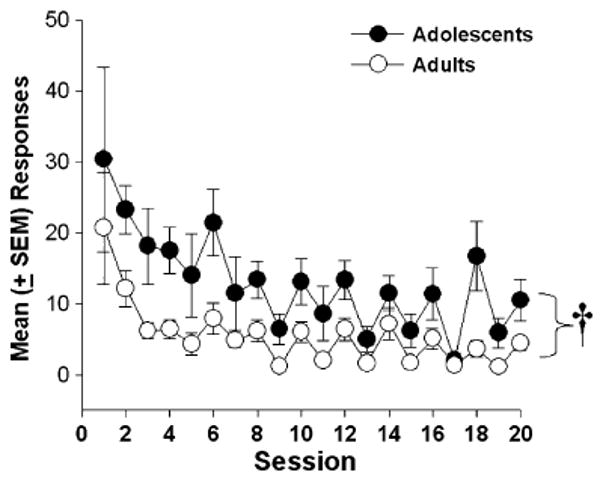

Extinction

Figure 2 shows the mean number of extinction responses made following the removal of cocaine and cocaine-paired cues. Results indicated that adolescents responded significantly more than adults during extinction testing (F1, 55=15.17, p<0.001) and that both groups showed a significant reduction in responding on the previously drug-paired lever during the second half of extinction testing (sessions 11–20) compared to the first half (sessions 1–10; F1, 55=15.41, p<0.001). Analysis of inactive lever presses revealed that adolescents also responded more on the inactive lever than adults (F1, 53=8.32, p<0.001). Further analysis indicated no difference in active vs inactive lever responding in adolescent rats. Both active and inactive responses significantly decreased during the second half (vs first half) of extinction testing in adolescent rats (F1, 53=5.98, p<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Mean (± SEM) responses on the previously drug paired lever during 20 2-h sessions following the removal of cocaine. Adolescents (n=14), compared to adults (n=15), responded significantly more on the previously drug-paired lever over the 10 days (†p<0.05)

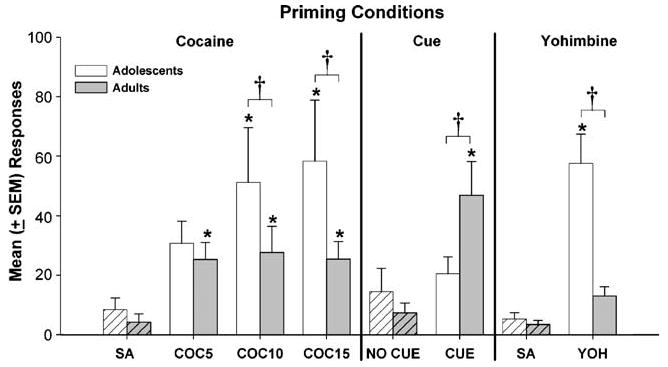

Reinstatement

Figure 3 shows the mean number of reinstatement responses made on the previously drug-paired lever during the priming and control conditions. There was a significant main effect of priming for all eight conditions (F7, 183=8.07, p<0.0001) and a significant group×priming condition interaction (F7, 183=3.62, p<0.01). For the cocaine-priming condition, injections of 10- and 15-mg/kg cocaine resulted in significantly higher reinstatement responding than saline-priming injections in the adolescent and adult groups (p's<0.05). However, only adults responded significantly more than saline following the lowest priming dose of cocaine (5 mg/kg). Group comparisons indicated that adolescents responded significantly more than adults following the two largest doses of cocaine (10 and 15 mg/kg, p's<0.05) suggesting that there were age differences in cocaine-primed reinstatement.

Fig. 3.

Mean (± SEM) responses on the previously drug-paired lever following saline (SA) or cocaine (COC; 5, 10, and 15 mg/kg) i.p. priming injections, cues, and 2.5-mg/kg yohimbine (YOH) i.p. priming injections during the reinstatement procedure in adolescent (n=8) and adult rats (n=14). Responses during priming sessions were compared to responses during control sessions (striped bars) that occurred that same day. Asterisks indicate significantly greater responding during the priming condition compared to the control condition within groups (*p<0.05). Daggers denote significant group differences in responding during the priming conditions (†p<0.05)

Age differences were also found in the cue-priming condition. For example, adults, but not adolescents, significantly increased reinstatement responding following presentations of cues previously paired with drug self-administration compared to a session when these cues were not present (p<0.01). Also, adults reinstated significantly more than adolescents during reinstatement testing with cues (p<0.01). In the yohimbine condition, adolescents, but not adults, significantly increased responding on the previously drug-paired lever following yohimbine (vs saline) administration (p<0.01), and adolescents responded significantly more than adults (p<0.01).

Inactive lever pressing was analyzed across the reinstatement conditions (not shown). Results from the ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of group (F1, 183=22.99, p<0.01) and priming condition (F7, 183=3.84, p<0.01) but no group×priming condition interaction. Adolescents made significantly more inactive lever presses during reinstatement than adults. Given this finding, an additional analysis was conducted to compare responding on the previously active and inactive levers in adolescent rats to determine if reinstatement responding was due to cocaine seeking or to general activity. Results indicated that adolescents responded significantly more on the previously active (vs inactive) lever (F1, 143=7.49, p<0.05), and this changed as a function of the priming condition as confirmed by a significant lever type× priming condition interaction (F7, 143=3.58, p<0.01). Post hoc analyses revealed that systemic injection of a priming dose of cocaine (5, 10, and 15 mg/kg cocaine; p's<0.05) or yohimbine (p<0.05) resulted in greater responding on the previously drug-paired lever compared to responding on the inactive lever in adolescents. However, adolescents did not show a significant difference in responding between levers following cue presentations. This indicates that the enhanced responding by adolescents during reinstatement testing following drug and yohimbine primes was a result of increased cocaine-seeking behavior and not increased responding in general.

Discussion

The present results demonstrated that adolescence is associated with heightened vulnerability to several aspects of cocaine-seeking behavior. Adolescents, compared to adults, maintained higher levels of cocaine intake, were more resistant to extinction of cocaine seeking, and exhibited higher levels of reinstatement responding precipitated by i.p. injections of cocaine or yohimbine. Adults, however, reinstated significantly more following presentations of cues previously associated with cocaine self-administration.

Results during the maintenance condition agreed with previous reports showing enhanced sensitivity to cocaine-induced psychomotor stimulation (Caster et al. 2005; Parylak et al. 2008; Snyder et al. 1998), greater cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Badanich et al. 2006; Brenhouse and Andersen 2008; Brenhouse et al. 2008; Zakharova et al. 2009b), faster rates of acquisition of cocaine self-administration (Perry et al. 2007), and heightened i.v. amphetamine self-administration in adolescent (vs adult) rodents (Shahbazi et al. 2008).

Other studies have shown no effect of age on i.v. cocaine self-administration in rats (Li and Frantz 2009; Schramm-Sapyta et al. 2009). However, several methodological differences may account for this discrepancy. For example, in this and a previous study demonstrating age differences in cocaine self-administration (Perry et al. 2007), rats were allowed to self-administer a smaller dose of cocaine (0.4 mg/kg) for extended periods of time (two, 2-h sessions or 6-h sessions). In other studies, rats were tested during limited-access conditions (daily 2-h sessions; Kerstetter and Kantak 2007; Li and Frantz 2009) using relatively large doses of cocaine (1.0 mg/kg; Kantak et al. 2007; Kerstetter and Kantak 2007) that may have produced a ceiling effect. Indeed, previous reports indicate that group differences (e.g., phenotype and sex) in drug self-administration are more readily expressed under extended access conditions and with lower doses of cocaine (Carroll et al. 2008, 2009; Lynch and Carroll 1999; Roth et al. 2004). Thus, it may be that age differences in responding reinforced by cocaine are expressed under similar access and/or low dose conditions.

In the present study, adolescents, compared to adults, also made more extinction responses on the previously drug-paired lever following the removal of cocaine. Similarly, Brenhouse and Andersen (2008) demonstrated that adolescent rats required significantly more extinction trials to extinguish place preference induced by cocaine, sometimes requiring over 70 extinction trials (Brenhouse and Andersen 2008). Increased extinction responding in adolescent rats may be related to impairments in response inhibition or impulsivity. In a study by Adriani and Laviola (2003) adolescent (vs adult) rodents made significantly more nonreinforced responses following discontinuation of a food reward under a modified delay-discounting procedure (Adriani and Laviola 2003). Interestingly, frontocortical neurocircuitry involved in the inhibition of previously reinforced behavior (Jentsch and Taylor 1999) is underdeveloped during adolescence (Casey et al. 2008; Galvan et al. 2006; Levesque et al. 2004), and dysfunction within this area is associated with increased impulsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse in adolescent humans (Schweinsburg et al. 2004; Underwood et al. 2008).

Together, results from the maintenance and extinction phases of the present study indicate that adolescent rats, compared to adults, are more sensitive to the reinforcing effects of cocaine and have a decreased ability to inhibit responding previously reinforced with drug. Findings from animal and human studies further suggest that this behavioral profile may be the result of altered activation in areas of the brain that control incentive motivation and inhibition. These studies indicate that several neurobiological changes occur in the mesolimbic and prefrontal cortices of the brain during adolescence, and these changes, or lack thereof, may incur heightened vulnerability to cocaine self-administration and increased cocaine seeking. Mesolimbic dopamine release is involved in attributing salience to natural rewards (Carelli and Deadwyler 1994; Schultz et al. 1993), in addition to altering subjective and behavioral responses to drugs of abuse such as cocaine (Di Chiara 1998). In both animals and humans, adolescence is characterized by heightened dopamine activity (increased dopamine synthesis and turnover) in mesolimbic areas of the brain (Chambers et al. 2003; Schepis et al. 2008) such as the nucleus accumbens (Andersen et al. 1997), suggesting heightened sensitivity to reward due to “overdeveloped” neurobiological reward-related responses (Casey et al. 2008). In contrast, results from studies using humans indicate that frontal cortical regions that regulate these limbic regions and are involved in the inhibition of potentially harmful and risky behaviors such as drug taking (Casey et al. 2008) are “underdeveloped”, as is evidenced by a slower onset of dendritic pruning (Montague et al. 1999; Tarazi et al. 1999), an indicator of neuronal maturation and heightened neural processing efficiency (Freeman 2006). Casey et al. (2008) suggest that the lag in maturation between limbic and prefrontal regions in adolescents results in behavior that is motivated by the activation of limbic areas (i.e., bottom-up) that is unhindered by prefrontal (i.e., top-down) control. Indeed, adolescent humans and animals show exaggerated limbic responses and underdeveloped prefrontal responses in anticipation of rewards (Casey et al. 2008; Galvan et al. 2006). Thus, with respect to the present study, increased cocaine seeking during the maintenance and extinction conditions may have been the result of underdeveloped frontocortical–limbic interconnectivity, resulting in increased cocaine self-administration during maintenance and decreased response inhibition during extinction.

During reinstatement testing in the present study, adolescents and adults showed differential patterns of cocaine seeking that were dependent on the priming stimulus. Adolescents reinstated significantly more following i.p. injections of cocaine and yohimbine, while adults responded more following presentation of cues previously paired with drug self-administration. One explanation for increased cocaine-primed reinstatement in adolescent rats may be related to activation of neurons in the nucleus accumbens, as delta-FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (FosB) levels dramatically increase following administration with cocaine. However, unlike dopamine levels that decrease shortly thereafter, delta-FosB proteins are enduring, and a single molecule reportedly lasts several weeks after its formation (Nestler et al. 2001). Due to its long-lasting nature, delta-FosB is associated with long-term increases in the sensitization and motivation to self-administer cocaine in mice (Colby et al. 2003) and is considered a vulnerability marker of drug addiction and relapse (Nestler 2008). Interestingly, adolescent mice show enhanced delta-FosB upregulation in the nucleus accumbens following chronic (7 days) cocaine administration when compared to adults (Ehrlich et al. 2002). Thus, in the present study, exposure to cocaine during the maintenance condition may have engendered increased sensitivity to cocaine to a greater extent in adolescents than adults, thereby enhancing the effects of cocaine on reinstatement responding in adolescent rats.

Stress is emerging as an important vulnerability factor in relapse in humans (Koob 2009; Sinha 2009). In the present study, adolescents reinstated more than adults following an i.p. injection of the pharmacological stressor yohimbine. Several explanations may account for this finding. For example, preclinical and clinical reports indicate that adolescents show exaggerated behavioral and neurobiological responses to environmental (e.g., foot shock and restraint) and pharmacological stressors (for review, see McCormick and Mathews 2007). An additional explanation may relate to differential effects of previous cocaine exposure on stress reactivity. In a study by Stansfield and Kirstein (2007), adult rats that were exposed to chronic cocaine during adolescence showed greater stress reactivity in an open field, as evidenced by less time spent in the center of the apparatus, compared to cocaine naïve rats. Similarly, Bolanos et al. (2003) reported that methylphenidate treatment during adolescence in rats increased sensitivity to stressful situations later as adults. Cocaine exposure during the maintenance condition in the present study may have rendered adolescent rats more susceptible to stress, thereby enhancing yohimbine's effects on cocaine seeking.

Opposite to the results with cocaine and yohimbine adults, compared to adolescents, were more sensitive to cues during reinstatement testing suggesting greater cue reactivity. These results support previous work by Li and Frantz (2009). In their study, adult rats reinstated significantly more following presentations of cocaine-related cues compared to younger rats that began self-administration during adolescence. A similar finding of heightened cue-induced reinstatement responding in adults (vs adolescents) was reported following morphine self-administration (Doherty et al. 2009). One interpretation of these findings may involve differences in amygdala functioning in adolescents vs adults. The amygdala is essential in the learning and memory of appetitive and aversive stimuli (Rubinow et al. 2009). In addition, cue (but not drug)-induced reinstatement is guided by activation of the amygdala (See 2005). Interestingly, adolescent vs adults underperform on tasks that rely on amygdala function (Rubinow et al. 2009), and this may be due to the amygdala being underdeveloped in adolescence (Cunningham et al. 2002; Rubinow and Juraska 2009). Thus, adolescents (vs adults) in the present study may have responded less to cues during reinstatement testing due to an underdeveloped memory system.

In the present study, adolescents (vs adults) self-administered significantly more cocaine and exhibited greater cocaine seeking during extinction and reinstatement following cocaine and yohimbine administration. However, it is unclear as to whether reinstatement responding in adolescent rats was influenced by greater cocaine intake during the preceding maintenance phase. Results from previous studies using similar reinstatement procedures indicated that cocaine-primed reinstatement was unaffected by cocaine intake during the preceding maintenance conditions (Keiflin et al. 2008; Leri and Stewart 2001). Additionally, despite lower cocaine intake in maintenance, adults responded significantly more than adolescents following cue-induced reinstatement. These findings suggest that group differences leading to reinstatement did not influence reinstatement responding in the present study.

Heightened cocaine seeking in the adolescents, may have been attributed to increased responding in general. Not only did adolescents make more responses on the active/drug-paired lever but they also responded significantly more on the inactive lever that was never paired with i.v. cocaine. However, comparison of active and inactive lever pressing across conditions indicated that adolescents responded significantly more on the active vs inactive lever during both the maintenance and reinstatement conditions. This indicates that adolescents preferred the lever associated or previously associated with cocaine, despite having increased inactive-lever responding. The increase in indiscriminate responding during extinction may reflect an underlying attention deficit or increased impulsivity. Indeed, as previously mentioned, adolescence in humans is characterized by attention deficits (Casey et al. 2008; Galvan et al. 2006; Levesque et al. 2004) and increased impulsivity (Gullo and Dawe 2008; Hayaki et al. 2005).

In summary, the present results indicated that adolescents self-administered more cocaine than adults. They also exhibited greater resistance to extinction once cocaine was removed and demonstrated increased cocaine seeking following drug and yohimbine priming injections under a reinstatement procedure than adults. Adults, on the other hand, showed more reinstatement responding than adolescents following presentations of cues previously associated with drug self-administration. These findings may be attributed to differences in the development of key brain areas involved in reward-, inhibitory-, stress-, and memory-related processes in adolescents and adults. Overall, the results suggest that adolescence is a period of increased vulnerability to several aspects of drug abuse.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants, R01 DA 003240-25, R01 DA019942-2, K05 015267-07 (MEC), and F31 DA 023301-02 (JJA). The authors would like to thank Luke Gliddon, Nathan Holtz, Emily Kidd, Paul Regier, Amy Saykao, Matthew Starr, Rachel Turner, and Natalie Zlebnik for their technical assistance.

References

- Adriani W, Laviola G. Elevated levels of impulsivity and reduced place conditioning with d-amphetamine: two behavioral features of adolescence in mice. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:695–703. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Dumont NL, Teicher MH. Developmental differences in dopamine synthesis inhibition by (+/−)-7-OH-DPAT. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356:173–181. doi: 10.1007/pl00005038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badanich KA, Adler KJ, Kirstein CL. Adolescents differ from adults in cocaine conditioned place preference and cocaine-induced dopamine in the nucleus accumbens septi. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;550:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badanich KA, Maldonado AM, Kirstein CL. Early adolescents show enhanced acute cocaine-induced locomotor activity in comparison to late adolescent and adult rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2008;50:127–133. doi: 10.1002/dev.20252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister SE, Tossmann P. Association between early onset of cigarette, alcohol and cannabis use and later drug use patterns: an analysis of a survey in European metropolises. Eur Addict Res. 2005;11:92–98. doi: 10.1159/000083038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluzzi JD, Wang R, Leslie FM. Acetaldehyde enhances acquisition of nicotine self-administration in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:705–712. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolanos CA, Barrott M, Berton O, Wallace-Black D, Nestler EJ. Methylphenidate treatement during pre- and periadolescence alters behavioral responses to emotional stimuli at adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1317–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni M, See RE. A comparison of the effects of different operant training experiences and dietary restriction on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenhouse HC, Andersen SL. Delayed extinction and stronger reinstatement of cocaine conditioned place preference in adolescent rats, compared to adults. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:460–465. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenhouse HC, Sonntag KC, Andersen SL. Transient D1 dopamine receptor expression on prefrontal cortex projection neurons: relationship to enhanced motivational salience of drug cues in adolescence. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2375–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5064-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brielmaier JM, McDonald CG, Smith RF. Immediate and long-term behavioral effects of a single nicotine injection in adolescent and adult rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, D'Amico EJ. Outcomes of alcohol treatment for adolescents. Recent Dev Alcohol. 2001;15:307–327. doi: 10.1007/978-0-306-47193-3_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli RM, Deadwyler SA. A comparison of nucleus accumbens neuronal firing patterns during cocaine self-administration and water reinforcement in rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7735–7746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07735.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Boe IN. Increased intravenous drug self-administration during deprivation of other reinforcers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:563–567. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Lynch WJ, Campbell UC, Dess NK. Intravenous cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake: phenotype and sex differences. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;161:304–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Anker JJ, Perry JL, Dess NK. Selective breeding for differential saccharin intake as an animal model of drug abuse. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:435–460. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ, Perry JL. Modeling risk factors for nicotine and other drug abuse in the preclinical laboratory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111–126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caster JM, Walker QD, Kuhn CM. Enhanced behavioral response to repeated-dose cocaine in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:218–225. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Wells EA, Miller J, Brewer D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of adolescent drug abuse treatment, assessment of risks for relapse, and promising approaches for relapse prevention. Int J Addict. 1990;25:1085–1140. doi: 10.3109/10826089109081039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlow BJ, Kirstein CL. Cocaine during adolescence enhances dopamine in response to a natural reinforcer. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA, Taylor JR, Potenza MN. Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1041–1052. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Acquisition of nicotine self-administration in adolescent rats given prolonged access to the drug. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:700–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Maisto SA. Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CR, Whisler K, Steffen C, Nestler EJ, Self DW. Striatal cell type-specific overexpression of DeltaFosB enhances incentive for cocaine. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2488–2493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02488.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois R, Reveillere C, Paus A, Berton L, Jouint C. Links between stress factors, mental health and initial consumption of tobacco and alcohol during pre-adolescence. Encephale. 2007;33:300–309. doi: 10.1016/s0013-7006(07)92043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MG, Bhattacharyya S, Benes FM. Amygdalo-cortical sprouting continues into early adulthood: implications for the development of normal and abnormal function during adolescence. J Comp Neurol. 2002;453:116–130. doi: 10.1002/cne.10376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D. Adolescent substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Liddle H, Titus JC, Kaminer Y, Webb C, Hamilton N, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. A motivational learning hypothesis of the role of mesolimbic dopamine in compulsive drug use. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:54–67. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty J, Ogbomnwan Y, Williams B, Frantz K. Age-dependent morphine intake and cue-induced reinstatement, but not escalation in intake, by adolescent and adult male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich ME, Sommer J, Canas E, Unterwald EM. Periadolescent mice show enhanced DeltaFosB upregulation in response to cocaine and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9155–9159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09155.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Pine DS, Hardin M. Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychol Med. 2006;36:299–312. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estroff TW, Schwartz RH, Hoffmann NG. Adolescent cocaine abuse. Addictive potential, behavioral and psychiatric effects. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1989;28:550–555. doi: 10.1177/000992288902801201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. Potentiation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by the anxiogenic drug yohimbine. Behav Brain Res. 2006;174:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine RG. Evaluative behavioral judgments and instrumental antisocial behaviors in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:956–967. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz KJ, O'Dell LE, Parsons LH. Behavioral and neurochemical responses to cocaine in periadolescent and adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:625–637. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MR. Sculpting the nervous system: glial control of neuronal development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullgrabe MW, Vengeliene V, Spanagel R. Influence of age at drinking onset on the alcohol deprivation effect and stress-induced drinking in female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Hare TA, Parra CE, Penn J, Voss H, Glover G, Casey BJ. Earlier development of the accumbens relative to orbitofrontal cortex might underlie risk-taking behavior in adolescents. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6885–6892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1062-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo MJ, Dawe S. Impulsivity and adolescent substance use: rashly dismissed as “all-bad”? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1507–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaki J, Stein MD, Lassor JA, Herman DS, Anderson BJ. Adversity among drug users: relationship to impulsivity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Cerbone FG. Parental substance use disorder and the risk of adolescent drug abuse: an event history analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I, Schulz KP, London ED, Newcorn JH. Inhibitory control deficits in childhood and risk for substance use disorders: a review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:239–258. doi: 10.1080/00952990802013334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:373–390. doi: 10.1007/pl00005483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantak KM, Goodrich CM, Uribe V. Influence of sex, estrous cycle, and drug-onset age on cocaine self-administration in rats (Rattus norvegicus) Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:37–47. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiflin R, Vouillac C, Cador M. Level of operant training rather than cocaine intake predicts level of reinstatement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:247–261. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter KA, Kantak KM. Differential effects of self-administered cocaine in adolescent and adult rats on stimulus-reward learning. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Brain stress systems in the amygdala and addiction. Brain Res. 2009;1293:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota D, Martin BR, Robinson SE, Damaj MI. Nicotine dependence and reward differ between adolescent and adult male mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:399–407. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Adriani W, Terranova ML, Gerra G. Psychobiological risk factors for vulnerability to psychostimulants in human adolescents and animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:993–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Stewart J. Drug-induced reinstatement to heroin and cocaine seeking: a rodent model of relapse in polydrug use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:297–306. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque J, Joanette Y, Mensour B, Beaudoin G, Leroux JM, Bourgouin P, Beauregard M. Neural basis of emotional self-regulation in childhood. Neuroscience. 2004;129:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Rezvani AH, Montoya D, Rose JE, Swartzwelder HS. Adolescent-onset nicotine self-administration modeled in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;169:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1486-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Lawrence SS, Petro A, Horton K, Rezvani AH, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Adolescent vs. adult-onset nicotine self-administration in male rats: duration of effect and differential nicotinic receptor correlates. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:458–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Frantz KJ. Attenuated incubation of cocaine seeking in male rats trained to self-administer cocaine during periadolescence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;204:725–733. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1502-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez B, Turner RJ, Saavedra LM. Anxiety and risk for substance dependence among late adolescents/young adults. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:275–294. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the acquisition of intravenously self-administered cocaine and heroin in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s002130050979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado AM, Kirstein CL. Cocaine-induced locomotor activity is increased by prior handling in adolescent but not adult female rats. Physiol Behav. 2005a;86:568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado AM, Kirstein CL. Handling alters cocaine-induced activity in adolescent but not adult male rats. Physiol Behav. 2005b;84:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Strang J. Age of first use and ongoing patterns of legal and illegal drug use in a sample of young Londoners. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:313–319. doi: 10.1081/ja-200049333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CM, Mathews IZ. HPA function in adolescence: role of sex hormones in its regulation and the enduring consequence of exposure to stressors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague DM, Lawler CP, Mailman RB, Gilmore JH. Developmental regulation of the dopamine D1 receptor in human caudate and putamen. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:641–649. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research. The National Academies; Washington D.C.: 2003. p. 209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Review. Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: role of DeltaFosB. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3245–3255. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW. DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11042–11046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu M, Ehrlich ME, Unterwald EM. Age-specific behavioral responses to psychostimulants in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obot IS, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Early onset and recent drug use among children of parents with alcohol problems: data from a national epidemiologic survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;65:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda SR, Andrews WW, Advis JP, White SS. Recent advances in the endocrinology of puberty. Endocr Rev. 1980;1:228–257. doi: 10.1210/edrv-1-3-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RH, Young SE, Hopfer CJ, Corley RP, Stallings MC, Crowley TJ, Hewitt JK. Developmental epidemiology of drug use and abuse in adolescence and young adulthood: evidence of generalized risk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parylak SL, Caster JM, Walker QD, Kuhn CM. Gonadal steroids mediate the opposite changes in cocaine-induced locomotion across adolescence in male and female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Krystal JH, Kaufman J. Practitioner review: adolescent alcohol use disorders: assessment and treatment issues. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1131–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Anderson MM, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Acquisition of i.v. cocaine self-administration in adolescent and adult male rats selectively bred for high and low saccharin intake. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, Birmaher B, Rao R, Williamson DE, Perel JM. Factors associated with the development of substance use disorder in depressed adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1109–1117. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the vulnerability to drug abuse: a review of preclinical studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow MJ, Juraska JM. Neuron and glia numbers in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala from preweaning through old age in male and female rats: a stereological study. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:717–725. doi: 10.1002/cne.21924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow MJ, Hagerbaumer DA, Juraska JM. The food-conditioned place preference task in adolescent, adult and aged rats of both sexes. Behav Brain Res. 2009;198:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Adinoff B, Rao U. Neurobiological processes in adolescent addictive disorders. Am J Addict. 2008;17:6–23. doi: 10.1080/10550490701756146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm-Sapyta NL, Walker QD, Caster JM, Levin ED, Kuhn CM. Are adolescents more vulnerable to drug addiction than adults? Evidence from animal models. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1585-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Apicella P, Ljungberg T. Responses of monkey dopamine neurons to reward and conditioned stimuli during successive steps of learning a delayed response task. J Neurosci. 1993;13:900–913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00900.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg AD, Paulus MP, Barlett VC, Killeen LA, Caldwell LC, Pulido C, Brown SA, Tapert SF. An FMRI study of response inhibition in youths with a family history of alcoholism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:391–394. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE. Neural substrates of cocaine-cue associations that trigger relapse. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2005;526:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi M, Moffett AM, Williams BF, Frantz KJ. Age- and sex-dependent amphetamine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0933-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shram MJ, Funk D, Li Z, Le AD. Periadolescent and adult rats respond differently in tests measuring the rewarding and aversive effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:201–208. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Modeling stress and drug craving in the laboratory: implications for addiction treatment development. Addict Biol. 2009;14:84–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder KJ, Katovic NM, Spear LP. Longevity of the expression of behavioral sensitization to cocaine in preweanling rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:909–914. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear L. Modeling adolescent development and alcohol use in animals. Alcohol Res Health. 2000a;24:115–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000b;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Heightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: implications for psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:87–97. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:631–642. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfield KH, Kirstein CL. Chronic cocaine or ethanol exposure during adolescence alters novely-related behaviors in adulthood. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:637–642. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazi FI, Tomasini EC, Baldessarini RJ. Postnatal development of dopamine D1-like receptors in rat cortical and striatolimbic brain regions: an autoradiographic study. Dev Neurosci. 1999;21:43–49. doi: 10.1159/000017365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres OV, Tejeda HA, Natividad LA, O'Dell LE. Enhanced vulnerability to the rewarding effects of nicotine during the adolescent period of development. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MD, Mann JJ, Huang YY, Arango V. Family history of alcoholism is associated with lower 5-HT2A receptor binding in the prefrontal cortex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter CS, Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Spear LP. Time course of elevated ethanol intake in adolescent relative to adult rats under continuous, voluntary-access conditions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1159–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Lee CY. Likelihood of developing an alcohol and cannabis use disorder during youth: association with recent use and age. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;92:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Opland E, Weller C, Latimer WW. The effectiveness of the Minnesota Model approach in the treatment of adolescent drug abusers. Addiction. 2000;95:601–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95460111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova E, Leoni G, Kichko I, Izenwasser S. Differential effects of methamphetamine and cocaine on conditioned place preference and locomotor activity in adult and adolescent male rats. Behav Brain Res. 2009a;198:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova E, Wade D, Izenwasser S. Sensitivity to cocaine conditioned reward depends on sex and age. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009b;92:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]