Abstract

Objective To assess the effectiveness of strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants on the outcomes of perinatal, neonatal, and maternal death in developing countries.

Design Systematic review with meta-analysis.

Data sources Medline, Embase, the Allied and Complementary Medicine database, British Nursing Index, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, BioMed Central, PsycINFO, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature database, African Index Medicus, Web of Science, Reproductive Health Library, and Science Citation Index (from inception to April 2011), without language restrictions. Search terms were “birth attend*”, “traditional midwife”, “lay birth attendant”, “dais”, and “comadronas”.

Review methods We selected randomised and non-randomised controlled studies with outcomes of perinatal, neonatal, and maternal mortality. Two independent reviewers undertook data extraction. We pooled relative risks separately for the randomised and non-randomised controlled studies, using a random effects model.

Results We identified six cluster randomised controlled trials (n=138 549) and seven non-randomised controlled studies (n=72 225) that investigated strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants. All six randomised controlled trials found a reduction in adverse perinatal outcomes; our meta-analysis showed significant reductions in perinatal death (relative risk 0.76, 95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.88, P<0.001; number needed to treat 35, 24 to 70) and neonatal death (0.79, 0.69 to 0.88, P<0.001; 98, 66 to 170). Meta-analysis of the non-randomised studies also showed a significant reduction in perinatal mortality (0.70, 0.57 to 0.84, p<0.001; 48, 32 to 96) and neonatal mortality (0.61, 0.48 to 0.75, P<0.001; 96, 65 to 168). Six studies reported on maternal mortality and our meta-analysis showed a non-significant reduction (three randomised trials, relative risk 0.79, 0.53 to 1.05, P=0.12; three non-randomised studies, 0.80, 0.44 to 1.15, P=0.26).

Conclusion Perinatal and neonatal deaths are significantly reduced with strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants.

Introduction

Perinatal and maternal mortality rates are high in developing countries, with more than 358 000 mothers1 and six million babies dying annually.2 The millennium development goals were set up to encourage improvement in social and economic conditions in the world’s poorest countries by 2015. Progress towards achieving goal 4 (reducing child mortality) and goal 5 (improving maternal health) has been uneven.

At present, about 60 million births in developing countries occur outside healthcare facilities.3 An estimated 52 million births occur without the assistance of a skilled birth attendant.3 Women often give birth outside of health facilities with the help of a traditional birth attendant4 (box). Reasons for this include financial, geographical, or cultural barriers to healthcare access.

Definitions and roles of traditional and skilled birth attendants5

Skilled birth attendant: an accredited health professional—such as a midwife, doctor, or nurse—who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth, and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management, and referral of complications in women and newborns.

Traditional birth attendant: a person who assists the mother during childbirth and who often acquires her skills by delivering babies herself or through an apprenticeship with other traditional birth attendants. Roles of a traditional birth attendant vary and often depend on local customs, interests, and expertise. Tasks can range from provision of intrapartum and postnatal care to domestic chores. Traditional birth attendants are often known and respected for their knowledge and experience. They are not usually salaried, and are often paid in kind.

Several interventions have been implemented to reduce perinatal and maternal mortality, often by focusing on skilled birth attendants and health facilities. However, owing to the deficit of skilled birth attendants5 and limited healthcare resources worldwide, the prospect of all births taking place within a health facility with skilled birth attendance has not materialised. At present, traditional birth attendants are thought to be present at more than 50% of births in developing countries, with attendance being as high as 90% in some countries.6

Training programmes for traditional birth attendants began more than 60 years ago in areas where maternal mortality was high. In 1994, more than 85% of developing countries had some form of training for traditional birth attendants7 to improve maternal and perinatal health. A Cochrane review described the potential of such training as “promising,”8 yet only one large, cluster randomised, controlled trial had been done at the time of this review. In view of this uncertainty, we did a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effectiveness of strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants on perinatal and maternal outcomes.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We searched databases for articles that assessed strategies for incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants in developing countries. We searched Medline, Embase, the Allied and Complementary Medicine database, British Nursing Index, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, BioMed Central, PsycINFO, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature database, African Index Medicus, Web of Science, Reproductive Health Library, and Science Citation Index (from database inception to April 2011). Hand searching complemented electronic searches, and we also checked reference lists. The search terms were “birth attend*”, “traditional midwife”, “lay birth attendant”, “dais”, and “comadronas”, which all refer to the definition provided in the box. We did not apply any language restrictions to the search.

Study selection and data extraction

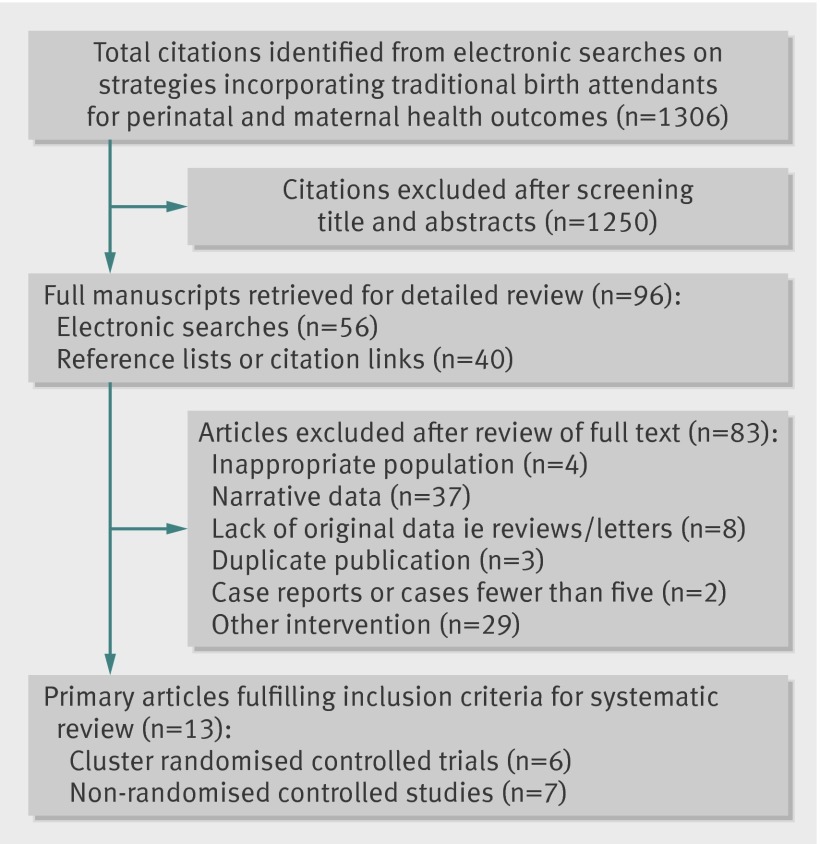

We selected both randomised and non-randomised controlled studies. Initially, we scrutinised the electronic searches and acquired full manuscripts of the relevant studies. Two reviewers (AW and AC) inspected the manuscripts before making final decisions on inclusion or exclusion (fig 1). Several reviewers (AW, CM, IG, NP, and JZ) extracted information from each article on study characteristics (web table), quality, and outcome data. We focused on outcomes of perinatal, neonatal, and maternal mortality that were objective and clinically relevant. We did not extract morbidity outcomes such as postpartum haemorrhage, obstructed labour, and neonatal apnoea, because they were assessed subjectively, often in a non-standardised manner, and differentially between the two study groups. For example, postpartum haemorrhage was described as “bleeding”,9 ”haemorrhage”,10 “heavy bleeding”,11 or “significant bleeding that soaked more than two kangas”,12 and was assessed by traditional birth attendants, skilled birth attendants, or by women giving birth themselves.

Fig 1 Flowchart of study selection

Methodological quality assessment

We assessed cluster randomised controlled studies for methodological quality using the CONSORT statement extension,13 to accommodate for the cluster effect within the data. These studies were assessed for randomisation and sequence generation, baseline comparability, accounting for cluster effect, blinding, and appropriate statistical analysis. We assessed non-randomised controlled studies for methodological quality using the Newcastle Ottawa scale.14 We considered the representativeness of the cohorts, selection of the cohorts, ascertainment of the intervention and the outcome, comparability of the cohorts, and the length and adequacy of follow-up. The risk of bias was deemed low if a study obtained four stars for selection, two stars for comparability, and three stars for ascertainment of exposure.14 Studies with two or three stars for selection, one for comparability, and two for exposure were considered to have a medium risk of bias. Any study scoring one or no stars for selection, comparability, or exposure was classed as having a high risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

The data from randomised and non-randomised controlled studies were pooled separately. We extracted data for effect estimates (risk ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals) directly from reports of cluster randomised controlled trials, after ensuring that the analyses had taken into account the cluster nature of the trial design. If a trial reported the effect estimate without accounting for cluster design, the standard error of the effect estimate from the analysis without clustering was multiplied by the square root of the estimated cluster effect. We then included these effect estimates and 95% confidence intervals in the meta-analysis using the generic inverse variance method and a random effects model. We assessed the heterogeneity of treatment effects using forest plots and χ2 tests, and determined the magnitude by calculating the I2 statistic. We used STATA 11.0 statistical software for analysis.

Results

Results of literature search

Figure 1 shows the process of literature search and selection, and gives reasons for exclusion of studies; the web table provides further details of the included studies. We included six cluster randomised controlled trials10 15 16 17 18 19 with a total of 138 549 participants (table 1) and seven non-randomised controlled studies9 20 21 22 23 24 25 with a total of 72 225 participants (table 2). The studies examined the effect of strategies incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants on perinatal and maternal mortality, within a wider interventional strategy with a multitude of components.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of cluster randomised controlled trials

| Adequate randomisation | Baseline comparability | Sample size calculation | Accounted for clustering | Masking | Loss of clusters to follow-up | Intention to treat analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman | Care provider | |||||||

| Jokhio 200510 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Carlo 201015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Azad 201016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Midhet 201019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Bhutta 201117 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Gill 201118 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

Table 2.

Quality assessment of non-randomised controlled trials

| Representativeness | Selection of comparison | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration of outcomes | Comparability | Outcome assessment | Length of follow-up | Adequacy of follow-up (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janowitz 198822 | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present** | Present* | Present* | >90 |

| Greenwood 199024 | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present* | Absent or not reported | Present* | Present* | >99 |

| Alisjahbana 19959 | Present* | Present* | Absent or not reported | Present* | Present** | Present* | Present* | >99 |

| Ronsmans 199721 | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present* | Absent or not reported | Present* | Present* | >99 |

| Bang 199925 | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present* | Absent or not reported | Present* | Present* | >90 |

| Gloyd 200120 | Absent or not reported | Present* | Absent or not reported | Present* | Present** | Present* | Present* | >99 |

| Bhutta 200823 | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present* | Present** | Present* | Present* | >99 |

One star (*)=half the maximum score for a specific quality item; two stars (**)=maximum score for a specific quality item.

Description of randomised controlled studies and interventions

All trials investigated complex interventions with various components (web table). We found substantial variation in the training and the role of traditional birth attendants, support staff, resources provided, and referral pathways. None of the trials provided a direct comparison of traditional birth attendants versus no attendants. Instead, the trials compared strategies that incorporated training and support10 or additional training and support of traditional birth attendants15 16 with strategies that did not provide any training and support or strategies that provided minimal training and support.

Some studies supported traditional birth attendants in both trial groups,15 16 18 but with an enhanced level of support given to the intervention group. For instance, Gill and colleagues15 supplied clean delivery kits to all traditional birth attendants in both control and intervention groups, in conjunction with basic training on newborn care and resuscitation. The intervention group also received training and protocols on advanced resuscitation techniques and on recognition of signs of neonatal sepsis.

In their trial, Azad and colleagues16 similarly provided both groups with basic training for traditional birth attendants including mouth to mouth resuscitation, although the intervention group received additional training in bag-valve-mask resuscitation. In the study by Carlo and colleagues,15 the intervention group received three days of intensive training in neonatal resuscitation and a refresher course, which the control group did not receive. Bhutta and colleagues17 provided their intervention group with an augmented training package for female (community) health workers, and a training programme for traditional birth attendants in basic newborn care and basic resuscitation; they also gave clean birth kits to female health workers.

The Jokhio10 and Midhet19 trials had the largest difference in strategies between comparison groups; traditional birth attendants received training and support only in the intervention group. These two trials also showed the largest improvement in perinatal mortality. Furthermore, they included referral pathways and resource support in the intervention groups, such as clean birth kits for traditional birth attendants.

Study quality

The six cluster randomised controlled trials were of high quality, when assessed with the CONSORT statement extension.13 They also had appropriate randomisation, comparability of clusters, accounting for cluster effect, and no loss of clusters to follow-up (table 1). The seven non-randomised controlled trials had a low to medium risk of bias for selection, and a low risk of bias for comparability and outcome assessment on the Newcastle Ottawa scale (table 2).

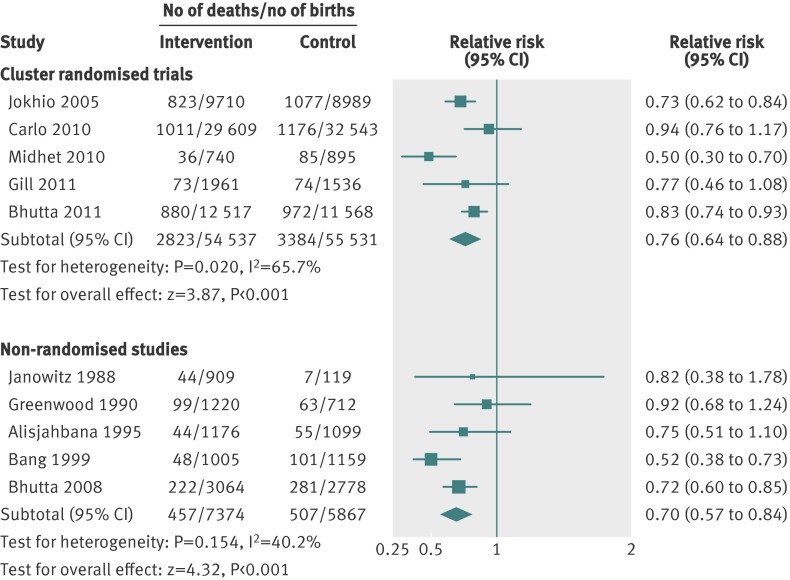

Perinatal mortality

Five cluster randomised controlled trials reported on perinatal mortality.10 15 17 18 19 All five trials showed a reduction in perinatal mortality, with three10 17 19 showing a significant reduction. Meta-analysis of the five studies showed a significant reduction in perinatal death (relative risk 0.76, 95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.88, P<0.001; number needed to treat in high risk population 35, 24 to 70; fig 2). We found heterogeneity between the studies (I2=65.7%). Five non-randomised controlled studies9 22 23 24 25 showed a very similar reduction in perinatal death (0.70, 0.57 to 0.84, P<0.001; 48, 32 to 96; fig 2), with some evidence of moderate heterogeneity (I2=40.2%) but it was not significant (P=0.15; fig 2).

Fig 2 Perinatal mortality. Midhet study did not report total births; denominator is number of live births. Perinatal mortality for Gill study comprised stillbirth and neonatal mortality within 1 week; effects of cluster design for both mortalities were estimated from standard errors, allowing estimation of cluster adjusted rate ratio for the combined outcome. Relative risk of perinatal mortality for Bhutta study was calculated with raw data for individual clusters

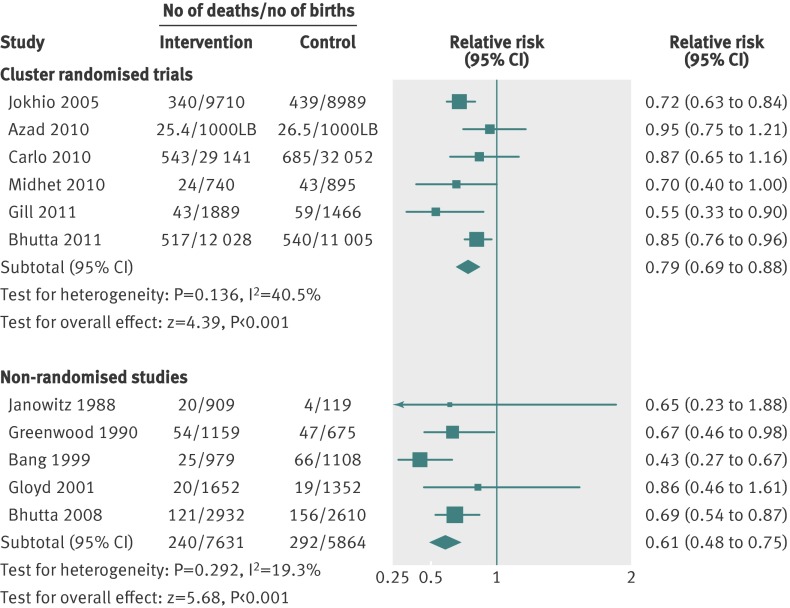

Neonatal death

All six cluster randomised controlled trials10 15 16 17 18 19 showed a reduction in neonatal mortality, with three10 17 18 showing a significant reduction. Meta-analysis of the six studies showed a significant reduction in neonatal death (relative risk 0.79, 95% confidence interval 0.69 to 0.88, P<0.001; number needed to treat in high risk population 98, 66 to 170; fig 3). We found moderate heterogeneity between the studies (I2=40.5%), although it was not significant (P=0.14; fig 3). Five non-randomised controlled studies20 22 23 24 25 also showed a reduction in neonatal death (0.61, 0.48 to 0.75, P<0.001; 96, 65 to 168; fig 3), with low heterogeneity (I2=19.3%).

Fig 3 Neonatal mortality. 1000LB=per 1000 live births. Midhet study did not report total births; denominator is number of live births. Relative risk of neonatal mortality for Bhutta study was calculated with raw data for individual clusters

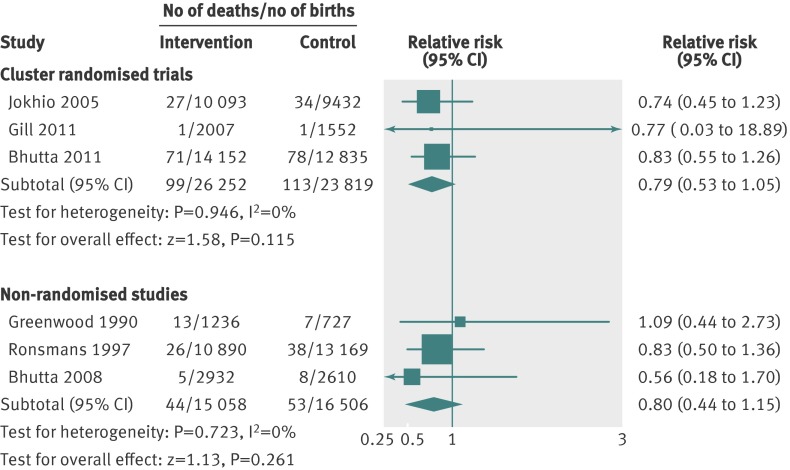

Maternal mortality

Three cluster randomised controlled trials10 17 18 reported on maternal mortality and found a non-significant reduction (relative risk 0.79, 95% confidence interval 0.53 to 1.05, P=0.12; fig 4). Meta-analysis of three non-randomised controlled studies21 23 24 also suggested a non-significant reduction in maternal death (0.80, 0.44 to 1.15, P=0.26; fig 4). We saw no evidence of heterogeneity in these analyses (I2=0%).

Fig 4 Maternal mortality. Effect of cluster design for Gill and Bhutta trials was estimated from standard errors of the other outcomes, allowing estimation of cluster adjusted rate ratio for maternal mortality

Discussion

Main findings of the study

Our meta-analysis of cluster randomised controlled trials showed that perinatal and neonatal deaths were significantly reduced with interventions incorporating the training, linkage, and support of traditional birth attendants. The findings from non-randomised controlled studies were entirely consistent with those from randomised controlled trials. This consistency was reflected in the level of heterogeneity in the randomised trials, which ranged from low to moderate and was significant in only one of the six analyses. Because all six randomised trials and five non-randomised studies showed a reduction in perinatal and neonatal mortality, the observed heterogeneity represented differences in the magnitude of a favourable effect found across studies, rather than suggesting any opposing effects. These estimated effects are large enough to contribute to a substantial improvement in perinatal outcomes in the developing world.

Meta-analysis of the randomised trials showed a non-significant reduction in maternal mortality, with the non-randomised studies confirming the trend. We saw no evidence of heterogeneity for maternal mortality within the studies.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The primary question for our review was whether strategies incorporating training, support, and linkage of traditional birth attendants, within the complex interventions as a whole, resulted in an improvement in perinatal, neonatal, and maternal outcomes (fig 5). Despite the heterogeneity in study populations, settings (countries), health systems, interventions, and comparisons, the consistency in our results contributes to the generalisability of the findings, which will be important for policy making.

Fig 5 Support for traditional birth attendants

We cannot infer that the greater the support for traditional birth attendants, the better the perinatal outcomes. Within a complex package of interventions, we would not be able separate the effect of enhanced support for traditional birth attendants and linkage with healthcare institutions, from that of other components in achieving these observed improvements.

We recognise the heterogeneity in the exact involvement of traditional birth attendants between the two groups of the included studies. The Carlo15 and Azad16 studies had the smallest differences in the training and support of traditional birth attendants. Therefore, we removed these two studies for a sensitivity analysis, and included only studies with a substantial difference between the two comparison groups in the training and support provided to traditional birth attendants. This sensitivity analysis showed increased effect sizes for perinatal mortality (relative risk 0.72, 95% confidence interval 0.59 to 0.85) and neonatal mortality (0.75, 0.64 to 0.86). In our meta-analysis, we excluded a subgroup of couples from the intervention group in the Midhet study,19 to reduce excessive heterogeneity within the comparison groups. However, our sensitivity analysis, which included the couples, indicated that the overall findings remained unchanged. The combined intervention group (comprising women and couples) had a pooled relative risk of 0.80 (95% 0.74 to 0.87) for perinatal mortality and 0.79 (0.70 to 0.88) for neonatal mortality, after we used a random effects model and adjusted for cluster design.

Comparison with other studies

The effect of incorporating traditional birth attendants into programmes to reduce perinatal and maternal mortality was examined in a Cochrane review8 in 2009. Since only one cluster randomised controlled trial existed at the time of the review, we could not draw firm conclusions from the statement that “traditional birth attendant training had promising potential to reduce perinatal and neonatal mortality when combined with health services; however the limited number of studies included did not provide the evidence needed.” Our meta-analysis, consisting of six cluster randomised controlled trials and seven non-randomised controlled studies, allows firm inferences to be drawn.

Another Cochrane review26 assessed the full range of community based intervention packages, which included strategies as diverse as nurse led nutrition counselling, stimulation exercises to improve psychomotor development in infants,27 distributing supplementary foods to poor families,28 and providing preschool education. Furthermore, several studies have emerged since this review. Darmstadt and colleagues3 reviewed the evidence for community based, skilled and traditional birth attendants, as well as community health workers, in improving perinatal and intrapartum outcomes. This review included one cluster randomised controlled trial with traditional birth attendants as an intervention that existed at the time of the review,10 and their findings on traditional birth attendants accorded with our present findings.

Conclusions and policy implications

Use of traditional birth attendants without an appropriate package of training, support, linkage with healthcare institutions, and resource supply is unlikely to be effective. Potentially important components that support strategies incorporating traditional birth attendants and that have been proved to be beneficial10 include training and support, as well as linkage with healthcare professionals, continued skill development, access to resources such as clean birth kits and resuscitation equipment, and effective referral pathways (fig 5).

The most effective intervention to improve perinatal and maternal outcomes is the use of skilled birth attendants. Although this intervention is a central goal, the economic, geographical, political, and social realities have limited the ability of national and international efforts to ensure the presence of skilled attendants at all births. This limited coverage has resulted in critical gaps, with 52 million women giving birth without skilled attendance every year.3 Therefore, other cadres of health workers might need to be considered to extend the coverage of maternal and neonatal care. Traditional birth attendants can improve the coverage of maternal and neonatal care, and evidence from this meta-analysis suggests that they can be a component of the strategies to improve perinatal outcomes. Traditional birth attendants often represent a more feasible, culturally acceptable, and accessible option for women in developing countries.11

Our systematic review and meta-analysis provides good quality evidence showing an average 24% reduction in perinatal death rates with strategies incorporating the training and support of traditional birth attendants. Enhanced access to care during pregnancy and labour, in areas with poor coverage of skilled birth attendants, can form part of the solution to meet millennium development goals 4 (reducing child mortality) and 5 (improving maternal health).

What is already known on this topic

More than 50% of births in developing countries are attended by traditional birth attendants, with the rate being as high as 90% in some countries

There is uncertainty about the effectiveness of including training and support for traditional birth attendants in strategies to improve perinatal and maternal health

What this study adds

Our meta-analysis showed that perinatal and neonatal deaths were significantly reduced with interventions incorporating training and support of traditional birth attendants. A non-significant reduction was evident in maternal mortality

Findings from non-randomised controlled studies were consistent with those from randomised controlled trials

Dedicated to the memory of Dr Heather Winter who, based on evidence from her randomised controlled trial in 2005, believed that strategies appropriately incorporating trained traditional birth attendants should be further investigated in reducing maternal and perinatal mortality in the developing world.

Contributors: AW and AC conceived the systematic review and selected the studies for inclusion. AW and IG undertook the literature search. AW, IG, NP, and JA extracted the data from selected studies. NP and JZ analysed the data. AW, AC, CM, IG, and DL were responsible for the data interpretation and discussion. AW and IG undertook the quality assessment of studies. DL, CM, and KK provided critical input. AC is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by Ammalife (www.ammalife.org, UK registered charity no 1120236) and by the research and development department at the Birmingham Women’s NHS Foundation Trust.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: this study was funded by Ammalife and the research and development department at the Birmingham Women’s NHS Foundation Trust; CM was partly funded by the National Institute for Health Research through the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country; no relationships with any institution that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;343:d7102

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web table: Study characteristics

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008 estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank. 2010. World Health Organization, 2010.

- 2.World Health Organization. Millennium development goals report: 2007. United Nations Department of Economical and Social Affairs. United Nations, 2007.

- 3.Darmstadt GL, Lee AC, Cousens S, Sibley L, Bhutta ZA, Donnay F, et al. 60 million non-facility births: who can deliver in community settings to reduce intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;107(suppl 1):S89-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan M. Training traditional birth attendants reduces maternal mortality and morbidity. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;1:44-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Coverage of maternity care, a listing of available information. 4th ed. WHO, 1996.

- 6.World Health Organization. Health in the millennium development goals. Millennium development goals, targets and indicators related to health. WHO, 2004.

- 7.Fleming JR. What in the world is being done about TBAs? An overview of international and national attitudes to traditional birth attendants. Midwifery 1994;10:142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibley LM, Sipe TA, Brown CM, Diallo MM, McNatt K, Habarta N. Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD005460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alisjahbana A, Williams C, Dharmayanti R, Hermawan D, Kwast BE, Koblinsky M. An integrated village maternity service to improve referral patterns in a rural area in West Java. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1995;48(suppl):S83-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jokhio AH, Winter HR, Cheng KK. An intervention involving traditional birth attendants and perinatal and maternal mortality in Pakistan. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussein AK, Mpembeni R. Recognition of high risk pregnancies and referral practices among traditional birth attendants in Mkuranga District, Coast Region, Tanzania. Afr J Reprod Health 2005;9:113-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prata N, Mbaruku G, Campbell M, Potts M, Vahidnia F. Controlling postpartum hemorrhage after home births in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;90:51-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004;328:702-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells G. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analysis. Proceedings of the third symposium on systematic reviews. Beyond the basics: improving quality and impact. Oxford, 2000.

- 15.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, Chomba E, Tshefu A, Garces A, et al. Newborn-care training and perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med 2010;362:614-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azad K, Barnett S, Banerjee B, Shaha S, Khan K, Rego AR, et al. Effect of scaling up women’s groups on birth outcomes in three rural districts in Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:1193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhutta ZA, Soofi S, Cousens S, Mohammad S, Memon ZA, Ali I, et al. Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: a cluster-randomised effectiveness trial. Lancet 2011;377:403-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill CJ, Phiri-Mazala G, Guerina NG, Kasimba J, Mulenga C, MacLeod WB, et al. Effect of training traditional birth attendants on neonatal mortality (Lufwanyama Neonatal Survival Project): randomised controlled study. BMJ 2011;342:d346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Midhet F, Becker S. Impact of community-based interventions on maternal and neonatal health indicators: results from a community randomized trial in rural Balochistan, Pakistan. Reprod Health 2010;7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gloyd S, Floriano F, Seunda M, Chadreque MA, Nyangezi JM, Platas A. Impact of traditional birth attendant training in Mozambique: a controlled study. J Midwifery Womens Health 2001;46:210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ronsmans C, Vanneste AM, Chakraborty J, van Ginneken J. Decline in maternal mortality in Matlab, Bangladesh: a cautionary tale. Lancet 1997;350:1810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janowitz B, Bailey P, Dominik R, Araujo L. TBAs in rural northeast Brazil: referral patterns and perinatal mortality. Health Policy Plan 1988;3:48-58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhutta ZA, Memon ZA, Soofi S, Salat MS, Cousens S, Martines J. Implementing community-based perinatal care: results from a pilot study in rural Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:452-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenwood AM, Bradley AK, Byass P, Greenwood BM, Snow RW, Bennett S, et al. Evaluation of a primary health care programme in the Gambia. I. The impact of trained traditional birth attendants on the outcome of pregnancy. J Trop Med Hyg 1990;93:58-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy MH, Deshmukh MD. Effect of home-based neonatal care and management of sepsis on neonatal mortality: field trial in rural India. Lancet 1999;354:1955-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lassi ZS, Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;11:CD007754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kafatos AG, Tsitoura S, Pantelakis SN, Doxiadis SA. Maternal and infant health education in a rural Greek community. Hygie 1991;10:32-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baqui AH, El-Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, Ahmed S, Williams EK, Seraji HR, et al. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:1936-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web table: Study characteristics