Abstract

Obesity has reached epidemic proportions throughout the globe, and this has also impacted people of the Arabic-speaking countries, especially those in higher-income, oil-producing countries. The prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents ranges from 5% to 14% in males and from 3% to 18% in females. There is a significant increase in the incidence of obesity with a prevalence of 2%–55% in adult females and 1%–30% in adult males. Changes in food consumption, socioeconomic and demographic factors, physical activity, and multiple pregnancies may be important factors that contribute to the increased prevalence of obesity engulfing the Arabic-speaking countries.

1. Introduction

An important factor contributing to obesity is the imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure. The WHO (World Health Organization) defines obesity as a BMI (body mass index) of 30 kg/m2 or more and considers obesity as a visible but neglected health issue that has only received recognition during the last 15 years [1]. The prevalence of obesity has risen in both developed and under-developed countries and has been particularly problematic in children [2]. Excess weight is the sixth most important risk factor for worldwide disease burden [3] and is associated with diabetes mellitus [4], hypertension [5], cerebral and cardiovascular diseases [6], various cancers [7], and sleep-disordered breathing [8].

There is an increased concern about obesity and its associated illnesses in the Arabic-speaking countries (East Mediterranean, Arabian peninsula, and northern Africa) and the factors which may be associated with it, including changes in social and cultural environments, education, physical activity, diet and nutrition, and difference in income and time expenditure [9–12]. This paper describes the prevalence of obesity in the Arab world and explores the factors that may lead to it.

2. Prevalence of Adulthood Obesity in Arab Countries

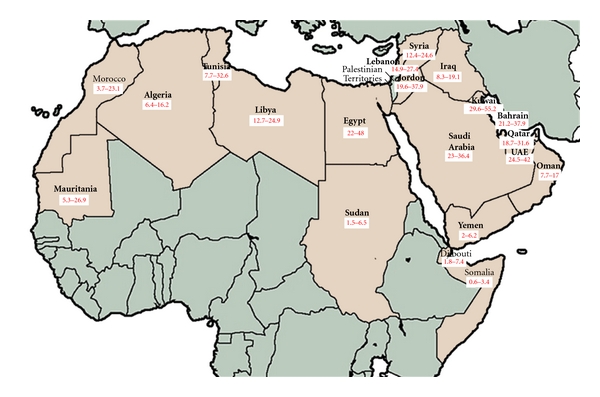

The prevalence of obesity has increased at an alarming rate during the last three decades, and this appears to be more pronounced in women. The prevalence of obesity parallels increased industrial development, which in the Arabian Gulf is related to the significant growths in incomes resulting from the rich deposits of oil reserves and the resultant impact on rapid urbanization and improved living conditions. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of obesity in the Arabic-speaking countries according to 2010 WHO estimates. For Kuwait, 30% of males and 55% of females over the age of 15 were classified as obese, making Kuwait the country with the highest prevalence of obesity in the Arabic-speaking countries [13]. Table 1 provides the 2010 WHO statistics for obesity prevalence in other developed and developing countries.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of obesity in Arabian countries in adult males and females, respectively, aged between 15 and 100 years, WHO estimates, 2010.

Table 1.

Ranking of the prevalence of obesity in Arabic and non-Arabic-speaking countries. The data are separated for males and females aged between 15 and 100 years, using WHO estimates for 2010. Arabic-speaking countries are shown in bold.

| Country | Male | Country | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 44% | Kuwait | 55% | |

| Greece | 30% | USA | 48% | |

| Mexico | 30% | Egypt | 48% | |

| Kuwait | 30% | UAE | 42% | |

| UAE | 25% | Mexico | 41% | |

| UK | 24% | Bahrain | 38% | |

| Saudi | 23% | Jordan | 38% | |

| Egypt | 22% | Saudi | 36% | |

| Bahrain | 21% | Tunisia | 33% | |

| Jordan | 20% | Qatar | 32% | |

| Qatar | 19% | Lebanon | 27% | |

| Israel | 18% | Mauritania | 27% | |

| Spain | 17% | Greece | 26% | |

| Lebanon | 15% | UK | 26% | |

| Belgium | 15% | Israel | 26% | |

| Italy | 14% | Syria | 25% | |

| Libya | 12% | Libya | 25% | |

| Syria | 12% | Morocco | 23% | |

| Iraq | 8% | Iraq | 19% | |

| Tunisia | 8% | Spain | 17% | |

| Oman | 8% | Oman | 17% | |

| Algeria | 6% | Algeria | 16% | |

| Mauritania | 5% | Italy | 14% | |

| Morocco | 4% | Belgium | 11% | |

| Yemen | 2% | Sudan | 7% | |

| Sudan | 2% | Somalia | 3% | |

| Somalia | 1% | Yemen | 2% |

3. Prevalence of Childhood and Adolescence Obesity in Arab Countries

Childhood obesity generally persists during adulthood; approximately one-third (26% male-41% female) of obese Arabic-speaking preschool children and half (42% male-63% female) of obese school-age children were also obese at adulthood according to a survey of data collected between 1970 and 1992 [31]. This suggests that screening for obesity at an early age may help to predict, and perhaps control, obesity later in life. One such screening tool is “adiposity rebound” which is defined as the age at which there is a rapid growth in body fat. Using this tool, one could predict whether an early adiposity rebound would lead to being overweight early in adulthood [32, 33]. Importantly, childhood obesity carries a greater risk of developing CVD (coronary vascular disease), hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, respiratory diseases, and some cancers. There is a significant correlation between BMI and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents [34]. Childhood obesity is also associated with increased psychosocial impact and reduced quality of life, for example, decreased self-esteem and physical functioning for children while their parents may undergo emotional distress due to the chronic concerns about their children's health [35]. Table 2 provides current information about obesity prevalence in children and adolescents in selected countries.

Table 2.

Prevalence of obesity (Arabic speaking in bold) in both males and females in a various countries. Data are for children and adults aged between 2 and 19.

| Arab country | Age | Male | Female | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahrain | 12–17 | 15% | 18% | [14] | |

| USA | 6–17 | 13% | 14% | [15] | |

| UAE | 5–17 | 13% | 13% | [16] | |

| Syria | 15–18 | 12% | 6% | [17] | |

| Kuwait | 5–13 | 9% | 11% | [18] | |

| Cyprus | 11–19 | 9% | 7% | [19] | |

| Qatar | 12–17 | 8% | 5% | [20] | |

| Lebanon | 3–19 | 8% | 3% | [21] | |

| Tunisia | 11–19 | 6% | 10% | [12] | |

| Egypt | 11–19 | 6% | 8% | [22] | |

| Brazil | 7–10 | 6% | 7% | [23] | |

| Saudi | 1–18 | 6% | 7% | [24] | |

| Bulgaria | 12–17 | 6% | 4% | [25] | |

| India | 2–17 | 5% | 4% | [26] | |

| France | 3–17 | 3% | 3% | [27] | |

| Poland | 7–17 | 3% | 1% | [28] | |

| Turkey | 12–17 | 2% | 2% | [29] | |

| China | 7–17 | 1% | 1% | [30] |

4. Factors Associated with Obesity in Arab Countries

The rapid development over the last 20 years in the Arab world has brought significant prosperity and easier life-styles in terms of transport, access to cheap migrant labor, proliferation of Western style fast food, and as elsewhere, greater opportunities for sedentary lifestyles. These reasons created an “obesogenic environment” around the Arabic-speaking countries.

5. Food Consumption

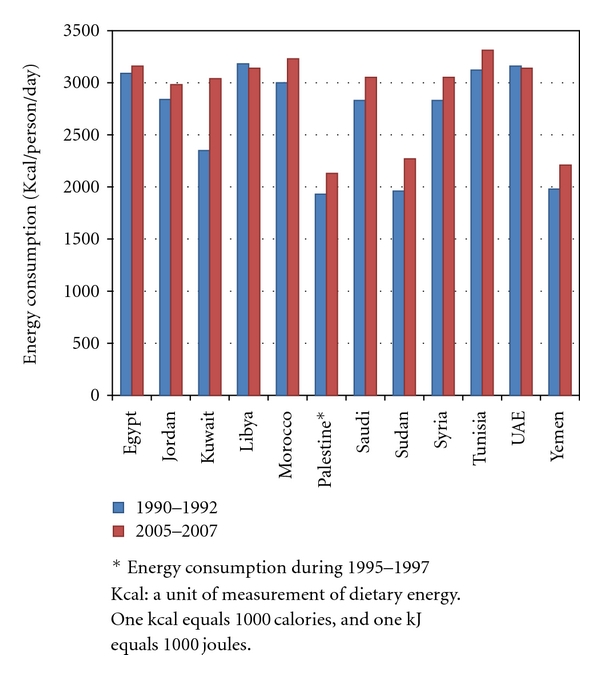

Westernization in Arabic-speaking countries has produced many western effects, most notably in the greater availability of food that is high in fats, sugar, and carbohydrates. In Lebanon, school children are abandoning the Mediterranean-style diet (cereals, vegetables, and fruits) in favor of adopting a largely fast-food-style diet [36]. The fat consumption in Lebanese children has increased from 24% to 34% during the period 1963–1998 [21]. Cultural considerations may aggravate the obesity problem further. For example in Saudi Arabia [37] and Kuwait [38], increased food intake is part of the socialization process, which is usually based on large gatherings where traditional meals consisting of rice (high carbohydrates) and meat (high fat) are shared. Even though people in Bahrain consume fresh fruit three times a week, they nonetheless eat fast food while watching TV; this has increased susceptibility to obesity [39]. The majority (93%) of the Iraqi overweight children eat between meals [40], and in Syria, obese people eat more than normal-weight people, regardless of the type of food they eat [41]. Figure 2 describes the dietary energy consumption per person in the Arab countries according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Statistics Division) from 1990 to 2007, where the average energy consumption per person is 2780 kcal/day [42].

Figure 2.

The dietary energy consumption per person, in kcal per day, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Statistics Division 2010, Food Balance Sheets).

6. Sociodemographic and Economic Factors

Urbanization increased with the modernization of Arab countries, and this has resulted in a large increase in obesity in cities and towns. For example, children in the rural southwestern region of Saudi Arabia have a lower rate of obesity (4%), likely because they participate in active lifestyles such as fishing and agricultural work; this is unlike the situation for children living in cities in the western (obesity prevalence of 10%) and eastern (14%) provinces (e.g., Jizan (12%), Ha'il (34%), or Riyadh (22%)) where a sedentary lifestyle and high-fat fast food consumption are commonplace [24, 37]. It has been reported that in the UAE, people living in isolated rural areas still maintain a Bedouin lifestyle and eat traditional foods and consequently also have lower obesity rates than those in urbanized areas [16]; similar data are also available for people living in rural areas of Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Palestine, and Oman [12, 22, 43, 44].

Income is also an important factor that can lead to obesity, especially in the Arabic-speaking oil-exporting countries. For example, meat consumption in Saudi Arabia increased by 500% while that in Jordan increased by 97% during the 1973–1980 period. High-income families in Kuwait consume more meat, eggs, and milk than families with low incomes [45]. A study in Egypt reports a lower rate of obesity in poorer people (3%) compared to those who may be more affluent (10%) [22]. Likewise, unemployed women in Syria have a higher rate of obesity (50%) compared to those who are employed (30%) [41]. Nonmodifiable risk factors in the rising tide of obesity in Arabic-speaking countries include the extreme outdoor temperatures that create desertification and the lack of forestation and vegetation in general, forcing people to remain indoors and resort to using cars to travel even relatively short distances.

Married people are more susceptible to being overweight and obese; in a randomized population study in Jordan, the prevalence of obesity in married adults was 54% (compared to 37% in unmarried adults), and the corresponding figures in Syria were 45% (21% in unmarried adults) [41, 49]. Similar findings are reported in studies done in other countries of the Arabian Gulf [39, 50, 51]. One reason for this could be that married couples are less active and tend to eat together, likely reinforcing increased food intake [52]. Education also plays a role in obesity prevalence since there is evidence that illiteracy increases the level of obesity in the Arabic-speaking countries. For example, 51% of illiterate Syrians are obese while 28% of people with a university education are obese [41]. Likewise, Jordanians with less than 12 years of education are approximately 1.6 times as likely to be obese than compatriots with more than 12 years of education [49]. Similarly, Lebanese with limited formal education are twice as likely to be obese [21]. Importantly, at least based on studies in Iraq, childhood obesity may be related to the educational background of the parents [40]. There may be a perception among some parents in the UAE that being overweight is a sign of high social status, beauty, fertility, and prosperity [16]. Table 3 shows a weak relation between income, literacy, and obesity in oil-producing countries with the exception of Saudi Arabia and UAE where high income and low literacy (compared to Russia and China) appear to be associated with increased obesity rates.

Table 3.

Obesity prevalence in oil-producing countries in males and females aged between 15 and 100 WHO, 2010, and their income and literacy rates.

| Country | Petrol production 2009 [46] (T bbl/day) | Literacy [47] | Income [48] | Obesity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ||||

| Russia | 9,934 | 99.4% | Upper middle income | 10% | 24% |

| Saudi | 9,760 | 78.8% | High income | 23% | 36% |

| USA | 9,141 | 99% | High income | 44% | 48% |

| China | 3,996 | 90.9% | Lower middle income | 4% | 4% |

| Mexico | 3,001 | 91% | Upper middle income | 30% | 41% |

| UAE | 2,795 | 77.9% | High income | 25% | 42% |

| Kuwait | 2,496 | 93.3% | High income | 30% | 55% |

| Venezuela | 2,471 | 93% | Upper middle income | 30% | 33% |

T bbl/day: thousand Barrels per Day.

M: males, F: females.

Sources: Oil production: EIA 2009; income: gross national income (GNI) per capita, World Bank classification 2009; literacy: The World Factbook, CIA 2009.

7. Physical Activity

Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle that results in energy expenditure above basal levels [53]. As discussed earlier, the rapid economic development in the Arabic-speaking countries has produced significant changes in socioeconomic status and lifestyle; the extensive road networks, increased availability of cars, greater use of mechanized home and farm appliances, widespread use of computers, televisions, and electronic gaming devices have encouraged a more sedentary lifestyle that leads to greater accumulation of body fat. In Framingham children's study, children who watched television for more than 3 hours a day had a BMI of 20.7, while children who watched television for less than 1.75 hours a day had a BMI of 18.7 [54, 55]. Nearly 82% of Bahraini adults watch TV daily [39].

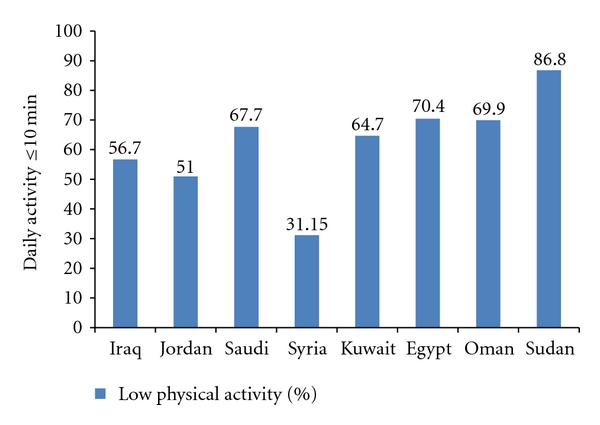

More than half (~57%) of boys aged 7–12 years old in Riyadh (Saudi Arabia) do not participate in even moderate levels (activity that raises the heart rate to above 139 beats per minute, for 30 minutes or more) [56], while 81% of adult males in Riyadh city are inactive, and an astounding 99.5% of adult females in Asir province reported no exercise (of any intensity) [57]. Only 2% of Egyptian adults exercise daily [9]. Figure 3 summarizes the daily physical activity lasting 10 minutes or lower of exercise in various Arabic-speaking countries [58].

Figure 3.

Prevalence of low physical activity in selected countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region according to the STEPwise survey done by WHO 2003–2007.

8. Obesity in Women from Arabic Speaking Countries

According to statistics from the WHO, Kuwait ranks 9th in the world and first amongst Arabic-speaking countries in female obesity. The rank order in Arabic-speaking countries for obesity in females is Kuwait (55.2%), Egypt (48%), and UAE (42%), which is higher than all the European countries and about the same as USA (48.3%) and Mexico (41%). Countries such as Bahrain (37.9%), Jordan (37.9%), Saudi Arabia (36.4%) and Lebanon (27.4%) have higher obesity rates in females than UK (26.3%), Greece (26.4%), and Israel (25.9%) [13].

Nearly 70% of women in Tunisia and Morocco are illiterate, a rate that is three times higher than in men, and it is likely that this may also contribute to a lack of appreciation of the health risks associated with obesity. The cultural desirability of some degree of obesity on grounds of beauty, fertility, and prosperity [12] may also contribute to the higher incidence of obesity in these countries. The association between the level of education and obesity is further exemplified in Syria, where obesity rate in women with low levels of formal education is 63%, while only 11% of women receiving advanced level education were likely to be obese [41].

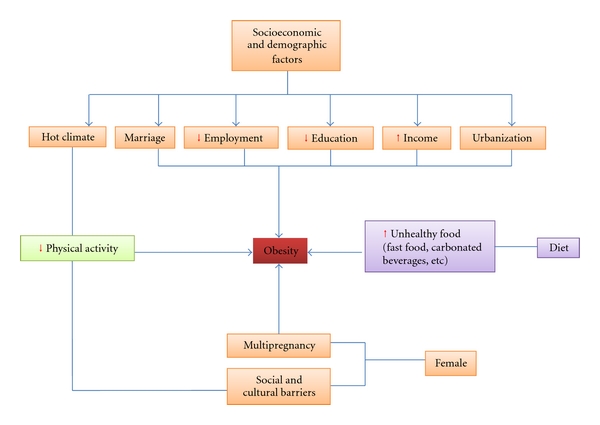

Traditional/cultural restrictions in lifestyle choices available to women in Arabic-speaking countries are one source for increased rates of obesity: females have limited access to sporting/exercise activities. This may be aggravated by the easy access to cheap migrant labor for domestic chores. For example, nearly all families in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia commonly employ cooks and maids—adding to a sedentary lifestyle in indigenous women [11, 38]. Nearly half of the women in Palestine and Syria have a sedentary lifestyle [41, 42], with TV being the main leisure activity reported by women in Bahrain [39]. Another important consideration for the high incidence of obesity in women in the Arabic-speaking nations is the role of multipregnancy. It is estimated that nearly 25% of women experience a weight gain of 4.55 kg or more 1 year postpartum, likely due to a combination of factors such as gestational weight gain, decreased physical exercise, and increased food intake [59]. Nearly 30% of Syrian women with 1 child are obese, and this prevalence increases to 75% for women with 7 children [41]. In Oman, a study showed a significant decrease in obesity prevalence (3.5%) between 1991 and 2000 attributed to decreased fertility in Oman [43]. All the factors discussed in this paper are summarized briefly in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diagram illustrating the factors that may lead to obesity in the Arabic-speaking countries.

9. Cost of Obesity

Obesity itself is not a disease; it is a risk factor for many noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and several others. Obesity has become an economic burden worldwide, and the cost of obesity can be estimated by determining the prevalence of obesity in a specific country and identifying the comorbidities related to it. Thereafter, a population attributable fraction (PAF) should be calculated for each comorbidity (PAF is calculated using the formula P(RR − 1)/[P(RR − 1) + 1], where P is the probability of a person being obese in a certain population and RR is the relative risk for the disease in an obese subject). The cost of each comorbidity is determined from data from health jurisdictions and includes direct costs of hospital care, physician and other health professional services, drugs, and other health care and health-care-related research costs. The cost attributable to each comorbidity is determined by multiplying the PAF by the total direct cost of the comorbidity so that the overall cost of obesity can be estimated as the total PAF-weighted costs of treating the comorbidities [60].

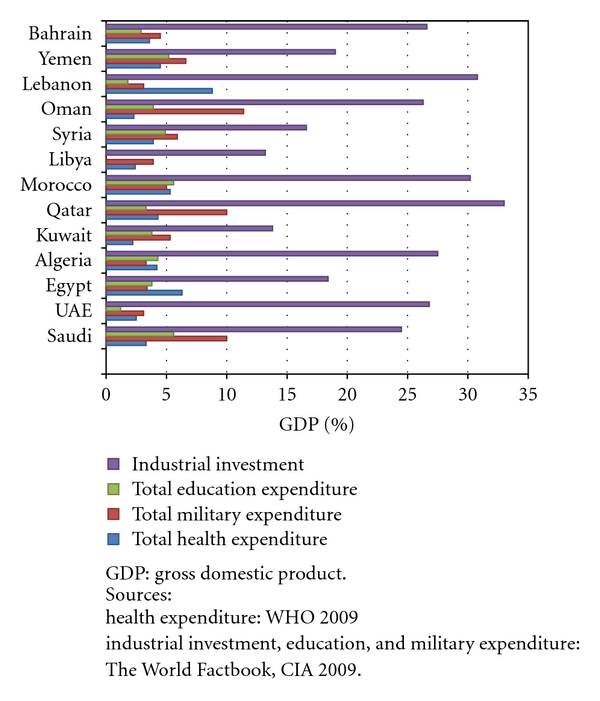

The Middle East and the six North African Arabic-speaking countries are among the world's top 10 in diabetes prevalence: the Middle Eastern countries are Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and UAE. Most of these countries have very high rates of obesity and diabetes, which contribute to the 290,000 deaths reported in this region in 2010 (or nearly 12% of all deaths in the 20–79 age group in 2010). These countries spend nearly 5.6 billion USD on diabetes-related health care [61]. As shown in Figure 5, most of the Arabic-speaking countries spend less than 7% of their GDP on health care systems and 6% on education, while spending 19–33% on industrial investment and reaching 11% on military services which is the highest in the world [47, 62]. Some of the reasons why health care systems in the Arabic-speaking countries are malfunctioning are that they are underresourced and perform below expectations, the chain of command consists of inefficient bureaucrats with political objective that often odds with public health, and the health professionals and support personnel are unequally distributed (concentrated in urban areas) [63].

Figure 5.

Industrial investment, military, education and health expenses percentage of GDP in selected Arabic-speaking countries.

10. Pharmaceutical Treatment of Obesity

Many medications have been used to treat obesity, but hardly any have created sustained weight losses in clinical trials, and disappointingly, no drug has been shown to be more effective than others when compared to placebo. Orlistat (a pancreatic lipase inhibitor that prevents the gut from digesting and absorbing dietary triacylglycerols) and sibutramine (a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressant that causes anorexia) are the most extensively studied drugs. The most important reason that limits the usefulness of many antiobesity drugs is related to their many, sometimes serious, side effects such as cramping and severe diarrhea (orlistat) and cardiovascular side effects and even reported deaths (sibutramine) [64]. Newer drugs such as rimonabant, which is the first of a new class of drugs that block the overactivity of the endocannabinoid system (activation of cannabinoid 1 receptors is associated with increased food intake, obesity, and dyslipidemia), have been tested in a phase III clinical trial (the RIO-Europe) where obese patients on a low calorie diet and treated daily for one year with 20 mg Rimonabant lost more than 10% of their initial weight with a concurrent improvement in their metabolic risk factors such as lipids and fasting glucose and insulin levels; importantly, there were mild and transient side effects (nausea and dizziness) associated with its use [65]. Even modest weight losses can influence obesity-associated diseases such as diabetes type 2, where a 5-6% weight loss combined with increased physical activity can reduce diabetes incidence by 58% [66].

There is a resurgent increase in the use of herbal extracts that induce weight loss and virtually have no side effects. One example is a Palestinian and Israeli study with 29 volunteers aged between 19 and 52 years, with an average weight of 94 kg; in this study, the volunteers ingested “Weighlevel” (a mixture of extracts of lady's mantle, mint and olive leaves, and cumin seeds—as used in traditional Greco-Arabic and Islamic medicine) without any other changes in their diet. After 3 months of treatment, the average weight of the subjects was 84 kg and average BMI dropped from 31 to 28 kg/m2 [67]. There does not appear to be other published data on the use of pharmaceutical therapy of obesity in Arabic-speaking countries.

11. Conclusion

Development, urbanization, and improved living conditions in the Arabic-speaking countries have led to greater consumption of unhealthy food intake; accompanied by decreased physical activity, this has caused an increase in prevalence of obesity in children, adolescents, and adults, especially women. However, there is a disproportionately low priority in governmental spending aimed at increasing awareness of the devastating heath care effects of obesity. Direct spending on health care and education (schools and universities) seems to have suffered at the expense of military enrichment and industrial development. There appears to be a lack of public awareness of healthy eating habits and the interaction of diet, exercise, and chronic diseases. There are significant cultural barriers that appear to affect women more; for example, managing their diet in pregnancy and postpartum and lack of communal exercise facilities for women.

References

- 1.Haslam DW, James WPT. Obesity. The Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1197–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obesity Reviews. 2004;5(1):4–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJL. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. The Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG. Weight change and duration of overweight and obesity in the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(8):1266–1272. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.8.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1983;67(5):968–977. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poirier P, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2002;4(6):448–453. doi: 10.1007/s11883-002-0049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceschi M, Gutzwiller F, Moch H, Eichholzer M, Probst-Hensch NM. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of obesity as a cause of cancer. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2007;137(3-4):50–56. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musaiger AO. Overweight and obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: can we control it? Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2004;10(6):789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papandreou C, Mourad TA, Jildeh C, Abdeen Z, Philalithis A, Tzanakis N. Obesity in Mediterranean region (1997–2007): a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2008;9(5):389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Mahroos F, Al-Roomi K. Overweight and obesity in the Arabian Peninsula: an overview. Journal of The Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 1999;119(4):251–253. doi: 10.1177/146642409911900410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokhtar N, Elati J, Chabir R, et al. Diet culture and obesity in northern Africa. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131(3) doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.887S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ono T, Guthold R, Strong K. WHO Global Comparable Estimates. 2005, https://apps.who.int/infobase/Comparisons.aspx.

- 14.Al-Sendi AM, Shetty P, Musaiger AO. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among Bahraini adolescents: a comparison between three different sets of criteria. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;57(3):471–474. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R. Child overweight and obesity in the USA: prevalence rates according to IOTF definitions. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2007;2(1):62–64. doi: 10.1080/17477160601103948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malik M, Bakir A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children in the United Arab Emirates. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8(1):15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasreddine L, Mehio-Sibai A, Mrayati M, Adra N, Hwalla N. Adolescent obesity in Syria: prevalence and associated factors. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2010;36(3):404–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorkhou I, Al-Qallaf K, Al-Shamali N, Hajia A, Al-Qallaf B. Childhood obesity in Kuwait—prevalence and trends. Family Medicine. 2003;35(7):463–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savva SC, Tornaritis MJ, Chadjigeorgiou C, Kourides YA, Siamounki M, Kafatos A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among 11-year-old children in Cyprus, 1997–2003. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2008;3(3):186–192. doi: 10.1080/17477160701705451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bener A. Prevalence of obesity, overweight, and underweight in Qatari adolescents. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 2006;27(1):39–45. doi: 10.1177/156482650602700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sibai AM, Hwalla N, Adra N, Rahal B. Prevalence and covariates of obesity in Lebanon: findings from the first epidemiological study. Obesity Research. 2003;11(11):1353–1361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salazar-Martinez E, Allen B, Fernandez-Ortega C, Torres-Mejia G, Galal O, Lazcano-Ponce E. Overweight and obesity status among adolescents from Mexico and Egypt. Archives of Medical Research. 2006;37(4):535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Assis MAA, Rolland-Cachera MF, Grosseman S, et al. Obesity, overweight and thinness in schoolchildren of the city of Florianópolis, Southern Brazil. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;59(9):1015–1021. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Hazmi MAF, Warsy AS. A comparative study of prevalence of overweight and obesity in children in different provinces of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2002;48(3):172–177. doi: 10.1093/tropej/48.3.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrova S. Current problems in nutrition of children in Bulgaria. GP News. 2005;12:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Cole TJ, Chiplonkar SA, Pandit D. Overweight and obesity prevalence and body mass index trends in Indian children. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2011;6(2):e216–e224. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.541463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lioret S, Touvier M, Dubuisson C, et al. Trends in child overweight rates and energy intake in France from 1999 to 2007: relationships with socioeconomic status. Obesity. 2009;17(5):1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chrzanowska M, Koziel S, Ulijaszek SJ. Changes in BMI and the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Cracow, Poland, 1971-2000. Economics and Human Biology. 2007;5(3):370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Öner N, Vatansever Ü, Sari A, et al. Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in Turkish adolescents. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2004;134(35-36):529–533. doi: 10.57187/smw.2004.10740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanping L, Evert GS, Xiaoqi H, Zhaohui C, Dechun L, Guansheng M. Obesity prevalence and time trend among youngsters in China, 1982–2002. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;17(1):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Preventive Medicine. 1993;22(2):167–177. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bray GA. Predicting obesity in adults from childhood and adolescent weight. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76(3):497–498. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labarthe DR, Eissa M, Varas C. Childhood precursors of high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol. Annual Review of Public Health. 1991;12:519–541. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.12.050191.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. 2005;111(15):1999–2012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedlander SL, Larkin EK, Rosen CL, Palermo TM, Redline S. Decreased Quality of Life Associated with Obesity in School-aged Children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157(12):1206–1211. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakar H, Salameh PR. Adolescent obesity in Lebanese private schools. European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16(6):648–651. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Othaimeen AI, Al-Nozha M, Osman AK. Obesity: an emerging problem in Saudi Arabia. Analysis of data from the national nutrition survey. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2007;13(2):441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Kandari YY. Prevalence of obesity in Kuwait and its relation to sociocultural variables. Obesity Reviews. 2006;7(2):147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musaiger AO, Al-Awadi AHA, Al-Mannai MA. Lifestyle and social factors associated with obesity among the Bahraini adult population. Ecology of Food Nutrition. 2000;39(2):121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lafta RK, Kadhim MJ. Childhood obesity in Iraq: prevalence and possible risk factors. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2005;25(5):389–393. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fouad MF, Rastam S, Ward KD, Maziak W. Prevalence of obesity and its associated factors in Aleppo, Syria. Prevention and Control. 2006;2(2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.precon.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.FAO Statistics Division. Food Balance Sheets, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy, 2010, http://faostat.fao.org/

- 43.Abdul-Rahim HF, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Stene LCM, et al. Obesity in a rural and an urban Palestinian West Bank population. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27(1):140–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Lawati JA, Jousilahti PJ. Prevalence and 10-year secular trend of obesity in Oman. Saudi Medical Journal. 2004;25(3):346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musaiger AO. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting food consumption patterns in the Arab countries. Journal of the Royal Society of Health. 1993;113(2):68–74. doi: 10.1177/146642409311300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petroleum Production, 2009. EIA, 2011, http://www.eia.gov/countries/

- 47.The World Factbook 2009. Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC, USA, 2009, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

- 48.The World Bank. Country and Lending Groups, The World Bank Group, Washington, DC, USA,2010, http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups.

- 49.Khader Y, Batieha A, Ajlouni H, El-Khateeb M, Ajlouni K. Obesity in Jordan: prevalence, associated factors, comorbidities, and change in prevalence over ten years. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. 2008;6(2):113–120. doi: 10.1089/met.2007.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Shammari SA, Khoja TA, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Nuaim LA. High prevalence of clinical obesity among Saudi females: a prospective, cross-sectional study in the Riyadh region. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1994;97(3):183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khashoggi RH, Madani KA, Ghaznawy HI, Ali MA. Socio-economic factors affecting the prevalence of obesity among female patients attending primary health centers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 1994;31(3-4):277–283. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeffery RW, Rick AM. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between body mass index and marriage-related factors. Obesity Research. 2002;10(8):809–815. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson G. Physical activity, exercise and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports. 1985;100(2):126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Proctor MH, Moore LL, Gao D, et al. Television viewing and change in body fat from preschool to early adolescence: the Framingham Children's Study. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27(7):827–833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giammattei J, Blix G, Marshak HH, Wollitzer AO, Pettitt DJ. Television watching and soft drink consumption: associations with obesity in 11- to 13-year-old schoolchildren. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157(9):882–886. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sallis J, Patrick K. Physical activity guidelines for adolescents: consensus statement. Pediatric Exercise Science. 1994;4(6):302–314. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Hazzaa HM. Prevalence of physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia: a brief review. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2004;10(4-5):663–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. STEPwise data from selected countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2003–2007, WHO EMRO, http://www.emro.who.int/ncd/stepwise.htm.

- 59.Oson CM, Strawderman MS, Hinton PS, Pearson TA. Gestational weight gain and postpartum behaviors associated with weight change from early pregnancy to 1 y postpartum. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27(1):117–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birmingham CL, Muller JL, Palepu A, Spinelli JJ, Anis AH. The cost of obesity in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1999;160(4):483–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Diabetes Atlas, International Diabetes Federation, 2010, http://www.diabetesatlas.com/content/middle-east-and-north-africa.

- 62.World Health Statistics 2009. World Health Organization, 2009, http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html.

- 63. Arab Human Development Report 2009, AHDR, http://www.arab-hdr.org/publications/contents/2009/ch7-e.pdf.

- 64.Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, et al. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;142(7):532–546. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bloom SR, Kuhajda FP, Laher I, et al. The obesity epidemic pharmacological challenges. Molecular Interventions. 2008;8(2):82–98. doi: 10.1124/mi.8.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Said O, Khalil K, Fulder S, Marie Y, Kassis E, Saad B. A double-blind randomised clinical study with “Weighlevel”, a combination of four medicinal plants used in traditional Greco-Arab and Islamic medicine. The Open Complementary Journal . 2010;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]