Abstract

Through the laboratory study of ancient solar system materials such as meteorites and comet dust, we can recognize evidence for the same star-formation processes in our own solar system as those that we can observe now through telescopes in nearby star-forming regions. High temperature grains formed in the innermost region of the solar system ended up much farther out in the solar system, not only the asteroid belt but even in the comet accretion region, suggesting a huge and efficient process of mass transport. Bi-polar outflows, turbulent diffusion, and marginal gravitational instability are the likely mechanisms for this transport. The presence of short-lived radionuclides in the early solar system, especially 60Fe, 26Al, and 41Ca, requires a nearby supernova shortly before our solar system was formed, suggesting that the Sun was formed in a massive star-forming region similar to Orion or Carina. Solar system formation may have been “triggered” by ionizing radiation originating from massive O and B stars at the center of an expanding HII bubble, one of which may have later provided the supernova source for the short-lived radionuclides. Alternatively, a supernova shock wave may have simultaneously triggered the collapse and injected the short-lived radionuclides. Because the Sun formed in a region where many other stars were forming more or less contemporaneously, the bi-polar outflows from all such stars enriched the local region in interstellar silicate and oxide dust. This may explain several observed anomalies in the meteorite record: a near absence of detectable (no extreme isotopic properties) presolar silicate grains and a dichotomy in the isotope record between 26Al and nucleosynthetic (nonradiogenic) anomalies.

Keywords: cosmochemistry, solar system origin

Planetary systems, including our own solar system, arise as a natural byproduct of star formation out of interstellar molecular clouds. In detail, many questions remain, and for which there are two complementary approaches. Astronomical observations of young protostellar objects show the process as is it happening essentially now, but the great distances involved limit our ability to resolve fine structure within protoplanetary disks. Laboratory studies of material from our own solar system, in particular of meteorites, comets, and interplanetary dust that are preserved more or less untouched since the birth of our solar system 4.568 Ga ago, yield chemical and physical clues to the large-scale processes and conditions extant at that time. These highly precise analytical measurements thus yield direct links between astronomical observations of large-scale processes in newly forming stellar systems and the same processes that occurred long ago in our solar system.

The Earth and other evolved large bodies in the solar system long ago lost all physical traces of the primordial grains from which they accreted. Very small bodies such as asteroids and comets, however, largely escaped planetary heating and melting and therefore do retain their original accretionary materials in varying degrees of preservation. Fortunately, comets plus collisions in the asteroid belt and elsewhere deliver some of this material into the inner solar system, where it falls to Earth in the form of meteorites, micrometeorites, and interplanetary dust. The likely significance of this material was recognized long ago. Goldschmidt (1) and Suess and Urey (2) compiled “cosmic” abundance tables for the elements, based in part on chemical analyses of chondrite meteorites. Suess and Urey (2) and later authors (e.g., ref. 3) compared the meteoritic abundances with measured abundances in the solar photosphere and found that, for most condensable elements (and other than gases), the match between CI chondrites in particular and the Sun was very close. As analytical techniques have improved, the match has also improved to the point at which most elements agree within approximately ±10% (reviewed in ref. 4). (Ref. 5 presents a recent review of chondrite classification, terminology, and properties.) However, although chondrites preserve grains from the earliest history of our solar system, most of those grains have not remained entirely pristine. CI and CM chondrites, for example, are composed primarily of hydrous phyllosilicates that probably formed by aqueous alteration of primary grains within asteroidal parent bodies. Possibly more pristine early solar system materials come from interplanetary dust particles (IDPs), which include both comet and asteroidal dust. Finally, we now have undoubted comet dust grains collected by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Stardust mission, which rendezvoused with Comet Wild 2 in 2004, collected dust particles from the comet's coma, and returned them to Earth in 2006. Collectively, the chondrites, IDPs, and stardust grains give us a window to the ancient past, when the solar system consisted only of a rotating dust and gas cloud surrounding the proto-Sun. Moreover, these materials provide information about different parts of the early solar system: Some chondrite grains formed very near the infant Sun and later accreted into parent bodies within the asteroid belt, whereas comets are thought to have accreted at the very fringes of the solar system. Surprisingly, the comet dust and IDPs and chondrites share many components in common, and this fact alone is (as detailed later) critical to understanding major physical transport processes within the infant solar system.

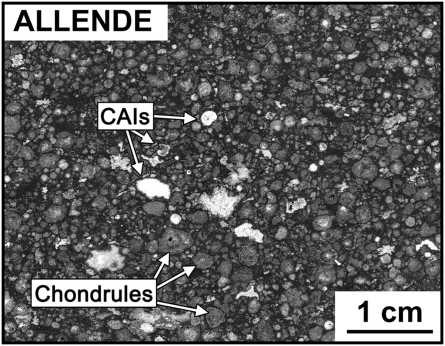

Undoubtedly the catalyst for the modern revolution in cosmochemistry was the fall, in February 1969, of the Allende meteorite in the northern desert of Mexico. In part, this is because of Allende being a rare type of meteorite, a CV3 carbonaceous chondrite. Even more remarkable were its size (more than 2 tons recovered) and the timing of the fall. Grossman (ref. 6, p. 559) characterized the situation aptly: “At a time when many of the world's geochemical laboratories were in close communication with each other and were perfecting their analytical techniques to derive the maximum information from a minimum of sample in preparation for the return of the first lunar rocks only six months thence, there were suddenly several tons of a single carbonaceous chondrite available for study.” However, the singularity of Allende does not stop there. Like all chondrites, Allende and the other CV3 chondrites are aggregates of preplanetary grains of diverse character (Fig. 1). The difference is in the grain size of some of these components. Immediately upon looking at a broken or cut face of Allende, one's eye is drawn to the prominent centimeter-sized white clasts (Fig. 1). Composed mainly of the oxides and silicates of aluminum, calcium, magnesium, and titanium, these clasts are referred to as refractory inclusions or (more commonly, and herein) calcium-aluminum–rich inclusions (CAIs). All chondrite varieties contain such objects, but in every other chondrite type, they are both rare and very small (<1 mm). In the CV3 chondrites, CAIs attain sizes as large as 2 cm. Had Allende been any type of chondrite other than a CV3, not only would the (rare and much smaller) CAIs have been missed, they could not have been analyzed easily with the types of instrumentation available at the time. The last piece of the Allende miracle again relates to timing. Although the size and peculiar nature of the CAIs in Allende quickly caught people's attention in 1969, interest was greatly raised because of other recent events. Larry Grossman was just completing his PhD thesis at Yale University, doing complete thermodynamic equilibrium calculations for the expected condensation of solids from a hot gas of solar composition (published in ref. 7). Although not the first to attempt such calculations, his were more comprehensive in terms of bulk chemistry and were the first to take specifically into account the changing composition of the gas as condensation proceeds. He showed that the first (i.e., highest temperature) major minerals to condense are oxides and silicates of calcium, aluminum, magnesium, and titanium. In other words, people in 1969 realized that the Allende CAIs potentially contain the first solid materials to have formed in our solar system. Allende provided us with just the right samples at just the right time. And because the Apollo samples were 6 mo yet to come, the new laboratories needed something to do. Within a few years of Allende's fall, two singular discoveries based on Allende CAIs would change the course of cosmochemistry. The first was the discovery (8) of excesses of 16O (relative to 17O and 18O) in Allende CAIs. The second was the discovery (9) of excess 26Mg that resulted from the in situ decay of 26Al at the time of CAI crystallization. There quickly followed the discovery in a rare few CAIs [referred to as FUN, for Fractionation and Unidentified Nuclear isotopic effects (10)] of intrinsic nuclear anomalies that could be traced back directly to presolar nucleosynthesis (e.g., ref. 11). Thus, the direct connection was first established between the analysis of solar system objects and astrophysical processes.

Fig. 1.

A cut surface of the Allende meteorite.

The present work is not and cannot be a comprehensive review. Rather, our aim is to highlight how cosmochemical studies have provided compelling evidence for some large-scale astrophysical processes during the formation of our solar system. At the end, we will address some remaining unanswered puzzles and speculate on one possible solution. We will touch only peripherally on the subject of the origin of nuclear anomalies and stellar nucleosynthesis, as this topic is covered elsewhere in this special issue of PNAS.

Triggered Star Formation in the Birth of Our Solar System

Star formation requires that portions of a interstellar molecular cloud cross a critical threshold of mass vs. size in order for them to become gravitationally bound and begin collapsing. In low-mass clouds like Taurus–Auriga, star formation arises as a result of turbulence-generated local density fluctuations, followed by loss of magnetic field support, cloud collapse and fragmentation, and continued gravitational collapse of the individual fragments. In giant molecular clouds like Orion, star formation can also be “triggered” by the effects of massive OB stars within the clouds. Numerically, most low-mass (i.e., Sun-like) stars form in giant molecular clouds (e.g., ref. 12). However, statistical considerations aside, there is direct cosmochemical evidence that our own Sun formed within a giant molecular cloud and that its formation was, indeed, triggered. The evidence primarily comes from the isotopic compositions of meteoritic components, including CAIs and chondrules.

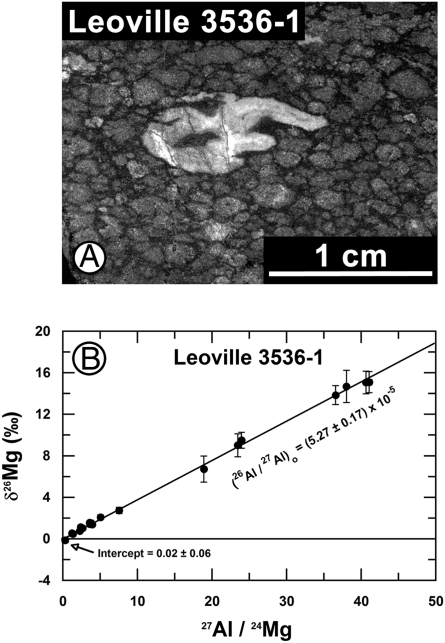

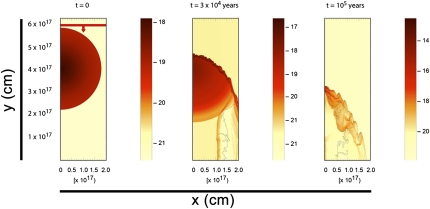

The idea behind the eventual discovery began with Urey (13), who predicted that the short-lived radionuclide 26Al might have existed in the earliest solar system and provided the heat source necessary for early planetary melting and differentiation. At that time, neither the instrumentation nor the proper samples existed to test the idea. Schramm et al. (14) revived the idea and measured a number of meteoritic samples in the search for the daughter product of 26Al decay, 26Mg, but again their analytical techniques were not sufficient to resolve any likely signature. Moreover, as it turned out, they still were not looking at the proper samples. Following the fall of Allende and the recognition of the CAIs as possible solar nebular condensates, several laboratories began in earnest the search for extinct 26Al. Finally, Lee et al. (9) demonstrated unambiguous evidence for the in situ decay of 26Al in an Allende CAI at a level much greater than the steady-state level throughout the interstellar medium. This result has been repeated and greatly amplified since then (reviewed in ref. 15; see example in Fig. 2) (16). The Lee et al. finding (9) of course raised the immediate question: Where did the excess 26Al come from? With a half-life of 0.71 Myr, it must have been made no more than 1 to 2 Myr before the time of CAI formation. This led Cameron and Truran (17) to propose that a nearby supernova not only triggered the collapse of the cloud that would become our solar system, but also seeded it with supernova ejecta that contained 26Al (Fig. 3 shows a modern numerical simulation of this process; ref. 18).

Fig. 2.

(A) A cut surface of the Leoville meteorite, showing a centimeter-sized CAI for which the magnesium isotope data (B) clearly indicate the in situ decay of 26Al at the time that the inclusion formed 4.56 billion years ago. The abundance ratio at the time of formation is given by the slope of the correlation line: 26Al/27Al = (5.27 ± 0.17) × 10−5. Data are from ref. 16.

Fig. 3.

Theoretical model of a supernova shock wave (top horizontal bar) striking a dense molecular cloud core, inducing dynamical collapse of the cloud, while simultaneously injecting short-lived radionuclides (black contours) into the collapsing cloud (modified from ref. 18). The color scales indicate gas density in g/cm3. The cloud is symmetrical around the left border. Models are shown as (A) initial model, (B) after 0.03 Myr, and (C) after 0.1 Myr.

This proposal was countered by an alternative idea (19) that local proton irradiation near our own infant Sun produced the 26Al, removing the need for any external source. The local-irradiation model has been debated at length, and the general consensus (not universal) is that it is unlikely for two reasons: (i) the difficulty of coproducing other known short-lived radionuclides (e.g., 41Ca, 53Mn) in their proper abundances relative to 26Al (reviewed in ref. 20); and (ii) 26Al is quantitatively not correlated with 10Be (reviewed in ref. 21), another short-lived radionuclide that is produced only by particle irradiation. Thus, if all the 10Be was made by local irradiation, most of the 26Al was made by some other mechanism. Aluminium 26 does correlate strongly with 41Ca, however (22)—another very short-lived nuclide—so those two nuclides must be cogenetic. It is not possible for particle irradiation to produce both in their observed relative proportions. Thus, plausible production sites for 26Al and 41Ca are asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars and supernovas, but AGB stars are highly evolved old Sun-like stars that generally are not located near the sites of stellar birth. Thus, the most likely source of early solar system 26Al and 41Ca is supernova injection. Because of the very short half-life of 41Ca, 105 years, that event must have occurred within approximately 1 Myr of the formation of CAIs in our solar system. The second and even stronger indication for a nearby supernova is 60Fe. Iron 60 cannot be produced by particle bombardment because there are no suitable target elements, and therefore its presence in meteorites is considered an unequivocal fingerprint of a nucleosynthetic origin. Shukolyukov and Lugmair (23, 24) first showed evidence for extinct 60Fe in the early solar system, in the form of Fe/Ni-correlated excesses of 60Ni (the daughter product of 60Fe) in eucrites (i.e., asteroidal basalts). There also is good evidence (e.g., ref. 25) for extinct 60Fe in chondrules, which are the small once-molten silicate droplets that characterize most chondrite meteorites. The 60Fe plausibly originated in either a supernova or an AGB star, but the supernova source can better explain other known short-lived radionuclides such as 53Mn (20). A third argument in favor of a supernova source is the advantage that supernova shock waves have over the winds from AGB stars in simultaneously triggering collapse of the presolar cloud and injecting enough freshly synthesized radionuclides into the collapsing cloud to match the inferred initial abundances in primitive meteorites (26).

The convincing evidence for a nearby supernova explosion at the time of our solar system's birth seemingly raises anew one original concern with the Cameron and Truran (17) proposal, namely the huge coincidence required. However, this argument has now been turned upside down (e.g., ref. 12) by the observation that, if our Sun formed in a giant molecular cloud whose evolution was largely controlled by early-formed massive O and B stars at its core, a supernova is actually to be expected. Such massive stars have lifetimes measured in millions rather than billions of years, and they would be expected to explode during the episode of star formation in large stellar “nurseries.”

Note that there is a critical difference between the newer “triggered star formation model” of Hester and Desch (12) versus the one proposed by Cameron and Truran (17) and later investigated by Boss and Keiser (18). In the Hester and Desch scenario (12), it is not the supernova shockwave itself that triggers the ongoing star formation. Rather, it is the outward-moving shock front of the ionized hydrogen (HII) region, a 10,000-K plasma, created by the intense stellar luminosity, radiation pressure, and stellar winds from the OB stars. In this scenario for our solar system, the supernova was responsible mainly for the late injection of short-lived radionuclides such as 26Al and 41Ca into the newly formed solar nebula, whereas in the original scenario, the supernova shock not only injects the short-lived radionuclides in the presolar molecular cloud core, but it simultaneously triggered collapse of the cloud.

Thus, precise measurements of grains within meteorites point to our sun and solar system having formed in a particular astrophysical environment: a giant molecular cloud, as opposed to the more quiescent environment of an isolated region analogous to the Taurus–Auriga cloud.

Nebula-Wide Mass Transport of Materials

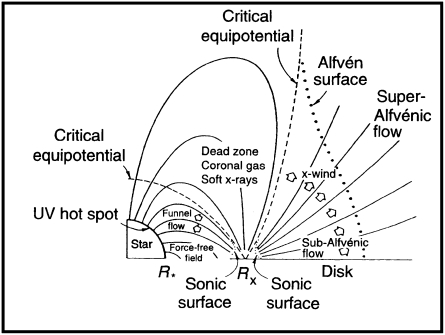

Chondrules and CAIs from chondritic meteorites formed at very high temperatures in the solar nebula, in excess of 1,200 °C, and some CAIs formed at temperatures approaching 2,000 °C. However, the chondrites themselves formed by relatively low-temperature accretion of solid grains in the general region of the asteroid belt. The temperature in the solar nebula dropped off radially away from the very hot center (near the proto-Sun), and at distances out near the asteroid belt the temperature probably was well below 1,000 °C (27). Thus, there has always been a problem reconciling the apparent formation temperatures of CAIs and chondrules with the location of their parent bodies in the asteroid belt. Early approaches to the problem involved exploring possible physical mechanisms that could lead to the transport of CAIs inside the disk from the very high temperatures of the inner nebula outward to much larger radial distances from the Sun (26). A somewhat different solution emerged when Shu et al. (28) proposed that CAIs and chondrules actually formed very close to the infant Sun but were expelled by magnetically driven bipolar outflows, up out of the plane of the disk (Fig. 4). Most of the material from these jets escapes into interstellar space, where it is observed in the form of Herbig–Haro objects, but some falls back onto the nebular disk far out from the Sun.

Fig. 4.

The X-wind model for driving bipolar outflow in a young star. In this model, CAIs are envisioned to form near the X-point at Rx, from which they can be launched upward and outward into interstellar space or the outer solar system. The X-point is located less than 0.1 AU away from the star, far inside the current orbit of Mercury. From Shu FH, Shang H, Lee T (1996) Toward an astrophysical theory of chondrules. Science 271:1545–1552. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

A second piece of the puzzle fell into place with the recognition that all CAIs have very similar oxygen isotopic compositions no matter what kind of chondrite in which they occur. However, the different chondrite classes themselves have distinctively different compositions. This implies that all CAIs formed out of the same restricted nebular isotopic reservoir and were later dispersed to their eventual chondrite accretion regions. McKeegan et al. (29) demonstrated that CAIs contained live 10Be at the time of their formation. Because this short-lived radionuclide forms by particle bombardment and not by stellar nucleosynthesis, the CAIs themselves must have formed very near a source of intense particle bombardment. That source likely was the infant Sun (refs. 29–31; but see ref. 32 for a dissenting opinion). Finally, the near-identity of CAI oxygen isotopic compositions with that of the Sun itself (33) all but confirms the idea that CAIs did form close to the proto-Sun and were physically transported outward into the solar system by some mechanism. However, the mechanism is still debated. Although bipolar outflow appears to be common among very young stars, the widely cited X-wind model of Shu et al. (28) is only one proposed model for producing such outflow. Desch et al. (34) critically examined the details of the X-wind model and concluded that it is not consistent with the properties of CAIs and chondrules. For example, temperatures at the X-point were so high that no solids could have existed there at all. Further, the relatively oxidizing conditions at the X-point are inconsistent with the extremely reduced mineral assemblages in CAIs. Finally, the relative abundances of most short-lived radionuclides identified with the earliest solar system cannot be explained by particle bombardment near the proto-Sun. Desch et al. (34) conclude that alternative mechanisms for producing bipolar outflow are more likely, that CAIs did not form at the X-point but farther out, 0.1 to 0.3 AU from the proto-Sun, and that most of the short-lived radionuclides originated from outside the solar system. Recent astronomical evidence also argues against the X-wind model. Extremely high-resolution spectral imaging (35) of the jet near the star DG Tau indicates a sharp velocity gradient within the jet, whereas the X-wind model predicts nearly constant velocity. Thus, Agra-Amboage et al. (35) conclude that the X-wind model cannot explain the properties of the DG Tau jet. That work and others (e.g., ref. 36) also specifically note that material in jets may come from a much wider radial distance from the central star than predicted by the X-wind model, perhaps as much as 1 AU (an important factor in preserving dust against evaporation). The preferred model of Agra-Amboage et al. (35) for bipolar outflows is a wind driven by the magnetic structure of the disk, not the central star.

Bipolar outflow is an attractive mass transport mechanism because it is observed to occur in contemporary young stars. However, other transport mechanisms have been proposed that do not involve bipolar outflow. Ciesla (e.g., ref. 37) suggested that particle diffusion within the disk itself led to grains being transported significant distances outward from the Sun over time scales of 0.1 to 1 Myr. Boss (38) showed that a phase of marginal gravitational instability is able to rapidly transport small particles from the inner disk to the outer disk while simultaneously homogenizing most initial isotopic heterogeneity, over time scales less than 0.001 Myr. It is possible that all three mechanisms operated in transporting grains outward from the Sun, but results from the Stardust sample return mission from Comet Wild 2 comet dust may pose a problem for the disk diffusion model. Terminal particles almost exclusively consist of anhydrous silicates, chondrule fragments, and even two CAIs, all materials commonly observed in chondritic (i.e., asteroidal) meteorites (39–42). Phyllosilicates and carbonates are virtually absent (39). The implication is that high-temperature grains from the inner solar system were very efficiently transported not just to the asteroid belt but also well beyond, to the region where Comet Wild 2 accreted. Westphal et al. (43) estimated that between 50% and 65% of the Stardust grains originated in the inner solar system. Depending on how early the gas giants formed, especially Jupiter, these planets could have posed a formidable obstacle to relatively slow outward diffusive transport of grains past Jupiter's orbit within the nebula midplane. If Jupiter formed rapidly and cleared away the local disk, and the Stardust grains did form in the inner solar system (but see below), it is more likely that these grains were transported outwards rapidly via bipolar outflow or by a phase of gravitational instability.

Presolar Silicates, the Stardust and FUN CAIs Enigmas, and the Source of Solar System Rocky Matter

Presolar grains in meteorites were first suspected to exist in meteorites because of anomalous isotopic compositions of the noble gases in bulk chondrites. Laborious chemical isolation procedures finally led to the separation and analysis of actual grains in 1987 (see ref. 44 for a historical review; also see ref. 45). This was first accomplished by dissolving >99% of the meteorites, tracking the isotope anomalies at every step, and when the grains bearing the anomalies were finally isolated, they turned out to be chemically resistant phases such as diamond, graphite, and SiC. Edward Anders famously described this procedure as burning down the haystack to find the needle. Other presolar phases were later identified, including corundum, spinel, and hibonite. Silicates were conspicuously missing. However, the compositions of Earth and the other rocky bodies require that silicates originally must have dominated the population of solids that went into the making of our solar system. The assumption was that the silicates were less able to survive the high-temperature processing in the early inner solar system, and those that did survive were later destroyed by the extreme chemical processing (described earlier) used in the laboratory to isolate presolar grains. Searches for presolar silicates required techniques that did not destroy the host meteorite, such as automated in situ isotopic scanning via secondary ion MS. Presolar silicates were eventually found, first in IDPs (46) and subsequently in chondrite meteorites (47), at a level of 300 to 400 ppm relative to the bulk meteorite. The existence of these grains is evidence that presolar silicates were not preferentially destroyed by high temperature processes everywhere in the solar system, and certainly not in the accretion regions where the host IDPs and primitive chondrites formed. How then to explain their low abundances even in such well preserved primitive materials?

This “abundance problem” is compounded by the results of the Stardust mission, a chief motivation of which was to return samples of solar system matter that had not experienced reprocessing in the inner solar system, such as was experienced by grains occurring in chondrites (e.g., ref. 47). Especially, there was an expectation that comet dust would contain a high fraction of presolar rocky material preserved from the interstellar medium. Thus, much of the returned material was expected to be amorphous and of low-temperature origin. However, as noted earlier, the returned grains instead consist of anhydrous crystalline materials such as olivine and pyroxene with variable but mostly low ferrous iron contents, CAIs (two so far), and chondrule fragments (39–42). All these grains resemble the kinds of inner solar system grains found in chondritic meteorites (41). Although some amorphous grains were found, it is by no means clear that these are primary as opposed to being products of the high-velocity impacts during sample collection (41). Very few presolar grains of any kind have been recognized, based on the criterion of isotopic compositions. However, this last statement may well lie at the very heart of the apparent abundance problem: What defines a presolar grain?

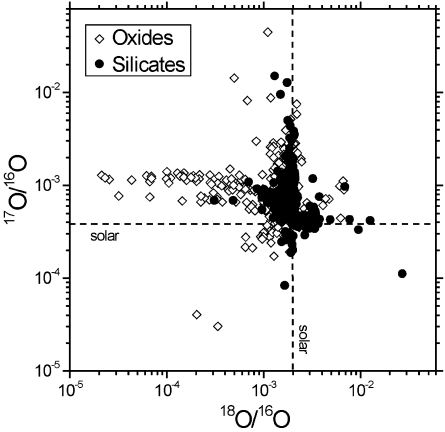

All presolar grains identified so far have extreme isotopic compositions that indicate the grains were derived from specific freshly nucleosynthesized material, from supernovas or novas or expelled shells of red giant stars (e.g., Fig. 5). However, the solar system in bulk does not have such compositions, and that difference enables identification of the presolar grains. The general explanation for the Stardust samples (e.g., refs. 41, 48) is that most of the grains were formed in the hot inner regions of the primitive solar nebula, near the Sun, and then transported outward to the comet-forming region. This imposes a number of singular requirements. First, almost no presolar silicates remained in the outermost parts of the solar system where the comets accreted. Most presolar material was transported inward and processed in the inner solar system, with very little escaping such processing. Second, the transport mechanism from the inner solar system to the outer solar system was remarkably efficient (43). And third, the isotopic composition of condensed (i.e., rocky) matter in the solar system is defined entirely by a mixture of supernova plus nova plus red giant grains. This scenario may be consistent with intermittent phases of gravitational instability in the gaseous disk (38).

Fig. 5.

Oxygen isotopic composition range of presolar oxide and silicate grains Figure courtesy of Dr. A. N. Nguyen; data sources given in ref. 47.

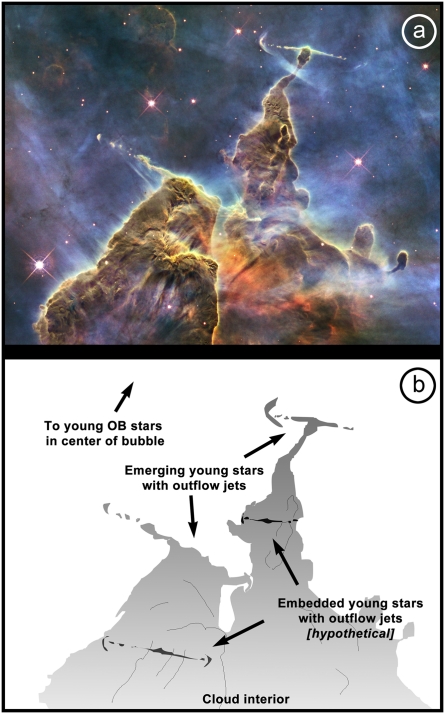

Individually and together, these three requirements might be met by a very different scenario. If our solar system formed in a giant star-forming region like Orion or Carina where triggered star birth occurred in the walls of the expanding bubble, a significant source of grains would have been the bipolar outflow of neighboring young stellar objects formed before (within a few million years at most) or contemporaneously with our own. Although grains are not directly observed in outflows from young stellar objects, they are generally accepted to be present because of the depletions of refractory elements from the gaseous component of the jets (e.g., refs. 35, 36). This idea has been considered before (e.g., ref. 49) but has not been examined in any serious way by cosmochemical means. Consider Fig. 6A, which shows a Hubble Space Telescope photo of the Carina Nebula. The two large columns of gas represent enhanced gas density at the edge of the bubble created in the middle of a large molecular cloud by nearby superenergetic O and B stars, and this is the region of triggered star formation. Young protostars are emerging from the tips of each of the two columns, with bipolar outflows clearly visible. Likely there are young protostars within the columns that are not visible (postulated in Fig. 6B). The outflow from the protostar at the lower left of Fig. 6A is even impinging on the sides of the column to its right, possibly propelling both gas and grains into that column's interior. Because star formation is enhanced in the bubble walls, there is likely to be a greatly enhanced enrichment of outflow grains relative to other kinds of interstellar grains. Moreover, because all the locally forming stars are born out of a common interstellar cloud, the bulk isotopic compositions of all of the other new solar systems would be similar to our own: The outflow-expelled grains would not be isotopically recognizable relative to what we think of as normal. The implication of this is that many or even most of the silicates in the most primitive meteorites or IDPs may be presolar, but they are not isotopically recognizable by current methods. Indeed, Bradley proposed such a model as far back as 1994 (50). Confirming this is an important scientific and technological challenge for the future, and a test of our model.

Fig. 6.

A portion of the Carina nebula showing two dense gas columns, each with a young (invisible) protostar at its tip; both protostars are undergoing bipolar outflow. (A) Note that the outflow from the star at lower left is impinging on the side of the neighboring column. (B) Line drawing of A shows hypothetical protostars in the hidden interiors of the gas columns, and again with bipolar outflow. Dust from such embedded stars would become fodder for later generations of protostars in the same cloud. Top photo courtesy of NASA, ESA, and M. Livio and the Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI).

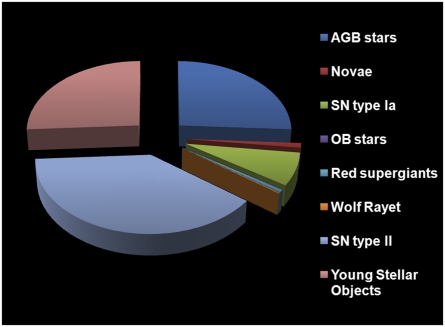

Tielens et al. (49) showed a diagram (Fig. 7) in which they attempted to estimate the relative contributions to the ISM grain population from different kinds of stellar sources. They adopted an upper limit of 30% for the fraction of interstellar dust might derive from young stellar objects; other authors have argued for a significantly lower fraction of less than 15% (e.g., ref. 51). Independent of what the actual fraction is, in a triggered star-forming region surrounding a large HII region, the fraction could well be higher by a factor of two or more.

Fig. 7.

Pie diagram showing the postulated fractions of interstellar dust grains that are contributed from each of plausible different stellar sources. Young stellar objects contribute as much as 30% according to this model (Discussion). Modified from ref. 49.

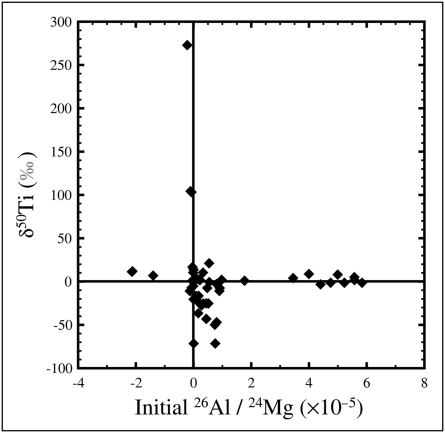

Near-contemporaneous stellar outflows from nearby infant stars may provide an explanation for another longstanding puzzle relating to the earliest history of our solar system. When the former presence of short-lived 26Al was first demonstrated (9) in an Allende CAI, those authors also analyzed a second CAI at the same time that did NOT once contain 26Al at detectable levels. This CAI and—as was later shown, a small number of similar objects—contain other unusual isotopic properties, specifically large degrees of mass-dependent isotopic fractionation in oxygen and magnesium plus nuclear (not derived from radioactive decay) anomalies in other elements such as calcium and titanium (e.g., refs. 11, 52). These rare (in CV3 chondrites) objects were named FUN inclusions in reference to their fractionation and unidentified nuclear effects (9). With the advent of secondary ionization MS (i.e., ion microprobe), it was subsequently found that much smaller objects (mainly single hibonite crystals) with similar isotopic properties occur in CM carbonaceous chondrites. Clayton et al. (53) reviewed (among other things) the data for FUN inclusions and presented a remarkable graph (Fig. 8) that shows a near-perfect noncorrelation between initial 26Al/27Al and 50Ti, which is a nuclear anomaly that can be used to identify FUN inclusions. This noncorrelation requires that the early solar system contained (at least) two very distinct isotopic reservoirs that did not mix, even when the grains were reheated and, on occasion, melted. Maintaining such distinct reservoirs in the gas phases is difficult, and is more readily explained if the isotopic signatures were preserved entirely in grains.

Fig. 8.

Initial 26Al/27Al ratios in early solar system refractory objects (mainly hibonite), plotted against 50Ti in the same objects. Data and original diagram are from ref. 53, and the modified diagram shown is reproduced from ref. 54. Reprinted from Meteorites, Comet And Planets: Treatise On Geochemistry, Vol 1, MacPherson GJ, Calcium aluminum-rich inclusions in chondritic meteorites, Pages 201-246, Copyright 2003, with permission from Elsevier.

The existence of FUN inclusions has been a riddle ever since their discovery, and nearly every model for the evolution of the early solar system has difficulty explaining them. For example, their lack of 26Al might imply that they formed long after “normal” CAIs. In that case, why do FUN CAIs preserve the nuclear anomalies that clearly are vestiges of nucleosynthetic processes? Alternatively, FUN CAIs might have formed at a much earlier stage of the early solar system than normal CAIs, in which case the 26Al itself must have been injected into the solar system after formation of FUN CAIs but before the formation of normal ones. A test of these hypotheses rests on obtaining a high-precision absolute age of a FUN CAI, a goal that has not yet been achieved because of the great rarity of large FUN CAIs in CV3 chondrites. However, there is a third possibility in the context of the model presented earlier. Other contemporary infant solar systems near our own, having similar bulk chemistry, would also have produced CAIs as well as other kinds of high-temperature grains near the respective young stars. It is quite possible that some of those systems might have had some isotopic differences relative to our own solar system, albeit nowhere near as great as those observed in supernova and nova and red-giant presolar grains. Such systems might, for example, largely have formed before the supernova that gave rise to the 26Al in our own system. The nuclear anomalies seen in FUN inclusions may reflect heterogeneous isotopic seeding elsewhere in the cloud by red giant stars or other (much earlier?) supernovas.

Summary and Conclusions

The laboratory study of ancient solar system materials provides extensive understanding for the astrophysical processes that formed out own solar system, processes that we can also observe to be occurring now in nearby star-forming regions. Studies of chondrite meteorites indicate that solid grains were evaporated, condensed, and melted in the hot innermost region of our solar system. Some of this highly processed material ended up much farther out in the solar system, not only the asteroid belt but even in the comet accretion region, suggesting a huge and efficient process of mass transport. Bipolar outflow is one possible mechanism for this transport in view of the fact that it is so common in young stars; turbulent diffusion and marginal gravitational instability may have contributed as well, although the effects of early-formed giant planets on interfering with turbulent diffusion are not yet well understood. The presence of short-lived radionuclides in the early solar system, such as 26Al and 41Ca, requires a nearby source of nucleosynthetic material shortly before solar system formation. The most likely source is a supernova, which is not only possible but probable if the Sun was formed in a massive star-forming region similar to Orion or Carina. In this case the solar system formation was “triggered” either by a supernova shock wave or by ionizing radiation originating from massive O and B stars at the center of an expanding HII bubble. Triggered formation of the solar system in a massive star-forming cloud can explain several observed anomalies in the meteorite record, such as the near absence of detectable presolar silicate grains and a complete dichotomy in the isotope record whereby 26Al and nucleosynthetic (i.e., nonradiogenic) anomalies were present in separate grain populations. The Sun would have formed in the dense border region of the expanding HII bubble, in close proximity to many other newly forming stars. Material expelled from these systems via bipolar outflow would become incorporated into any subsequently formed stars, and it would largely be isotopically indistinguishable from new grains formed in those systems because all originated from the same molecular cloud.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ann Nguyen for providing Fig. 5, Drs. John Bradley and Larry Nittler for helpful discussions, and two anonymous reviewers for very constructive suggestions that greatly improved the paper. G.J.M. would like to acknowledge the pioneering work of G. Herbig, who long ago considered the possibility that bi-polar outflow from young stars might be an important source of interstellar dust. This work was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Grants NNX11AD43G (to G.J.M.; Cosmochemistry program), NNX09AF62G (to A.P.B.; Origins of Solar Systems), and NASA Astrobiology Institute NNA09DA81A (to A.P.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Goldschmidt VM. Geochemische Verteilungsgestze der Elemente IX. Die Mengenverha¨ltnisse der Elemente und der Atom-Arten. Skrifter Utgitt av Det Norske Vidensk. 1938 Akad. Skrifter I. Mat. Naturv. Kl. (Oslo), No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suess HE, Urey HC. Abundances of the elements. Rev Mod Phys. 1956;28:53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders E, Ebihara M. Solar-system abundances of the elements. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1982;46:2363–2380. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palme H, Jones A. Solar system abundances of the elements. In: Holland HD, Turekian KK, editors. Meteorites, Comet And Planets: Treatise On Geochemistry. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier–Pergamon; 2003. pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott ERD, Krot AN. Chondrites and their components. In: Holland HD, Turekian KK, editors. Meteorites, Comet And Planets: Treatise On Geochemistry. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier–Pergamon; 2003. pp. 143–200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman L. Refractory inclusions in the Allende meteorite. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 1980;8:559–608. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman L. Condensation in the primitive solar nebula. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1972;36:597–619. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clayton RN, Grossman L, Mayeda TK. A component of primitive nuclear composition in carbonaceous meteorites. Science. 1973;182:485–488. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4111.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee T, Papanastassiou DA, Wasserburg GJ. Demonstration of 26Mg excess in Allende and evidence for 26Al. Geophys Res Lett. 1976;3:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wasserburg GJ, Lee T, Papanastassiou DA. Correlated oxygen and magnesium isotopic anomalies in Allende inclusions: II. Magnesium. Geophys Res Lett. 1977;4:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCulloch MT, Wasserburg GJ. Ba and Nd isotopic anomalies in the Allende meteorite. Ap. J. Letters. 1978;220:L15–L19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hester JJ, Desch SJ. Understanding our origins: Star formation in HII region environments. In: Krot AN, Scott ERD, Reipurth B, editors. Chondrites and the Protoplanetary Disk. Vol. 341. San Francisco: ASP Conference Series; 2005. pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urey HC. The cosmic abundances of potassium, uranium, and thorium and the heat balances of the Earth, the Moon, and Mars. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1955;41:127–144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.41.3.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schramm DN, Tera F, Wasserburg GJ. The isotopic abundance of 26Mg and limits on 26Al in the early solar system. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1970;10:44–59. [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacPherson GJ, Davis AM, Zinner EK. The distribution of aluminum-26 in the early Solar System: A reappraisal. Meteoritics. 1995;30:365–386. [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacPherson GJ, et al. Early solar nebula condensates with canonical, not supracanonical, initial 26Al/27Al ratios. Astrophysical Journal Letters. 2010;711:L117–L121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron AGW, Truran JW. The supernova trigger for formation of the solar system. Icarus. 1977;30:447–461. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boss AP, Keiser SA. Who pulled the trigger: A supernova or an asymptotic giant branch star? Astrophys J. 2010;717:L1–L5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee T. A local proton irradiation model for isotopic anomalies in the solar system. Astrophys J. 1978;224:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goswami JN, Vanhala HAT. Extinct radionuclides and the origin of the solar system. In: Mannings V, Russell SS, Boss AP, editors. Protostars and Planets IV. Tucson: Univ Arizona Press; 2000. pp. 965–994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKeegan K, Davis AM. In: Meteorites, Comet And Planets: Treatise On Geochemistry. Holland HD, Turekian KK, editors. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier–Pergamon; 2003. pp. 431–460. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahijpal S, Goswami JN, Davis AM, Grossman L, Lewis RS. A stellar origin for the short lived nuclides in the early solar system. Nature. 1998;391:559–561. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukolyukov A, Lugmair GW. Fe-60 in eucrites. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1993a;119:159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukolyukov A, Lugmair GW. Live iron-60 in the early solar system. Science. 1993b;259:1138–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.259.5098.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telus M, et al. Program and Abstracts from the 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Houston: Lunar and Planetary Institute; 2011. Possible heterogeneity of 60Fe in chondrules from primitive ordinary chondrites. LPI contribution 1608, p 2559. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boss AP, Keiser SA, Ipatov SI, Myhill EA, Vanhala HAT. Triggering collapse of the presolar dense cloud core and injecting short-lived radioisotopes with a shock wave. I. Varied shock speeds. Ap. J. 2010;708:1268–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boss AP. Temperatures in protoplanetary disks. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 1998;26:53–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu FH, Shang H, Lee T. Toward an astrophysical theory of chondrules. Science. 1996;271:1545–1552. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKeegan KD, Chaussidon M, Robert F. Incorporation of short-lived (10)Be in a calcium-aluminum-rich inclusion from the Allende meteorite. Science. 2000;289:1334–1337. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacPherson GJ, Huss GR, Davis AM. Extinct 10Be in type A CAIs from CV chondrites. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2003;67:3165–3179. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goswami JN, Marhas KK, Chaussidon M, Gounelle M, Meyer BS. Origin of short-lived radionuclides in the early solar system. In: Krot AN, Scott ERD, Reipurth B, editors. Chondrites and the Protoplanetary Disk. Vol. 341. San Francisco: ASP Conference Series; 2005. pp. 485–514. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desch SJ, Connolly HC, Jr, Srinivasan G. An interstellar origin for the Beryllium 10 in calcium-rich, aluminum-rich inclusions. Astrophys J. 2004;602:528–542. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKeegan KD, et al. The oxygen isotopic composition of the Sun inferred from captured solar wind. Science. 2011;332:1528–1532. doi: 10.1126/science.1204636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desch SJ, Morris MA, Connolly HC, Boss Alan P. A critical examination of the X-wind model for chondrule and calcium-rich, aluminum-rich inclusion formation and radionuclide production. Astrophys J. 2010;725:692–711. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agra-Amboage V, Dougados C, Cabrit S, Reunanen J. Sub-arcsecond [Fe II] spectro-imaging of the DG Tau jet: Periodic bubbles and a dusty disk wind? Astron Astrophys. 2011;532:idA59. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podio L, Medves S, Bacciotti F, Eislöffel J, Ray TP. Physical Structure and Dust Reprocessing in a sample of HH Jets. Astron Astrophys. 2009;506:779–788. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciesla FJ. Residence times of particles in diffusive protoplanetary disk environments. I. Vertical motions. Astrophys J. 2010;723:514–529. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boss AP. Mixing in the solar nebula: Implications for isotopic heterogeneity and large-scale transport of refractory grains. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2008;268:102–109. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zolensky M, et al. Comparing Wild 2 particles to chondrites and IDPs. Meteorit Planet Sci. 2008;43:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura T, et al. Chondrulelike objects in short-period comet 81P/Wild 2. Science. 2008;321:1664–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1160995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishii HA, et al. Comparison of comet 81P/Wild 2 dust with interplanetary dust from comets. Science. 2008;319:447–450. doi: 10.1126/science.1150683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matzel JEP, et al. Constraints on the formation age of cometary material from the NASA Stardust mission. Science. 2010;328:483–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1184741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westphal AJ, et al. Mixing fraction of inner solar system material in comet 81P/WILD2. Ap. J. 2009;694:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anders E, Zinner E. Interstellar grains in primitive meteorites: diamond, silicon carbide, and graphite. Meteoritics. 1993;28:490–514. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis AM. Stardust in meteorites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19142–19146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Messenger S, Keller LP, Stadermann FJ, Walker RM, Zinner E. Samples of stars beyond the solar system: Silicate grains in interplanetary dust. Science. 2003;300:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1080576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen AN, Nittler LR, Stadermann FJ, Stroud RM, Alexander CM O'D. Coordinated analyses of presolar grains in the Allan Hills 77307 and Queen Elizabeth Range 99177 meteorites. Astrophys J. 2010;719:166–189. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brownlee D, et al. Comet 81P/Wild 2 under a microscope. Science. 2006;314:1711–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1135840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tielens AGGM, Waters LBFM, Bernatowicz TJ. Origin and evolution of dust in circumstellar and interstellar environments. In: Krot AN, Scott ERD, Reipurth B, editors. Chondrites and the Protoplanetary Disk. Vol. 341. San Francisco: ASP Conference Series; 2005. pp. 605–631. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradley JP. Chemically anomalous, preaccretionally irradiated grains in interplanetary dust from comets. Science. 1994;265:925–929. doi: 10.1126/science.265.5174.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dwek E, Scalo JM. The evolution of refractory interstellar grains in the solar neighborhood. Astrophys J. 1980;239:193–211. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee T, Papanastassiou DA, Wasserburg GJ. Ca isotopic anomalies in the Allende meteorite. Astrophys J. 1978;220:L21–L25. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clayton RN, Hinton RW, Davis AM. Isotopic variations in the rock-forming elements in meteorites. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 1988;325:483–501. [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacPherson GJ. Calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions in chondritic meteorites. In: Holland HD, Turekian KK, editors. Meteorites, Comet And Planets: Treatise On Geochemistry. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier–Pergamon; 2003. pp. 201–246. [Google Scholar]