Abstract

Prions are unconventional infectious agents that cause transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) diseases, or prion diseases. The biochemical nature of the prion infectious agent remains unclear. Previously, using a protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) reaction, infectivity and disease-associated protease-resistant prion protein (PrPres) were both generated under cell-free conditions, which supported a nonviral hypothesis for the agent. However, these studies lacked comparative quantitation of both infectivity titers and PrPres, which is important both for biological comparison with in vivo-derived infectivity and for excluding contamination to explain the results. Here during four to eight rounds of PMCA, end-point dilution titrations detected a >320-fold increase in infectivity versus that in controls. These results provide strong support for the hypothesis that the agent of prion infectivity is not a virus. PMCA-generated samples caused the same clinical disease and neuropathology with the same rapid incubation period as the input brain-derived scrapie samples, providing no evidence for generation of a new strain in PMCA. However, the ratio of the infectivity titer to the amount of PrPres (specific infectivity) was much lower in PMCA versus brain-derived samples, suggesting the possibility that a substantial portion of PrPres generated in PMCA might be noninfectious.

Keywords: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, amyloid, neurodegeneration, protein polymerization, protein aggregation

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are fatal neurodegenerative diseases of humans and animals. TSE diseases include scrapie in sheep, chronic wasting disease (CWD) in cervids, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle as well as kuru, Gerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome (GSS), and familial, sporadic, iatrogenic, and variant forms of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in humans. A hallmark of prion diseases is the accumulation in infected tissues of a partially protease-resistant isoform of the prion protein (PrP), PrPres, also known as PrPSc. PrPres is generated by misfolding and aggregation of host-encoded protease-sensitive prion protein, PrPsen (1). PrPsen is required for susceptibility to prion infection and for pathogenesis and transmission of prion diseases (2, 3).

The biochemical nature of prion infectivity has been difficult to define. Early filtration studies favored a viral agent (see ref. 4 for review). However, a nonviral self-replicating protein agent was proposed in 1967 by Griffith (5), in part on the basis of the difficulty in inactivating scrapie infectivity. In 1982, in gradient fractions enriched for scrapie infectivity, Prusiner and coworkers identified a protease-resistant protein later named PrP (6), and this protein was proposed to be the infectious scrapie agent (7). By electron microscopy scrapie-associated fibrils (8) and prion rods (9) isolated from scrapie brain were described, and both contained PrP as a major component (10, 11). However, presence of a viral agent has remained difficult to exclude (for reviews see refs. 12–14).

The process of conversion of PrPsen to PrPres has been studied as a possible model of replication of prion infectivity, and this conversion has been modeled in several cell-free in vitro systems. This work is important because if significant infectivity were amplified in a cell-free reaction, this result would exclude a virus as the agent. In vitro systems for PrPres amplification include cell-free conversion (15), protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) (16), amyloid seeding assay (17), and quaking-induced conversion (18). Although PrPres can be generated in all of these systems, it has been difficult to demonstrate convincingly that infectivity is also produced. In some cell-free systems the level of input infectivity used to seed the reaction is too high to allow detection of newly generated infectivity (19). Alternatively when a very low input seed is used, the output of new infectivity has been barely detectable despite the rather large amount of protease-resistant PrP generated (20). In contrast, in PMCA reactions where whole brain homogenates containing PrPsen are seeded with scrapie brain PrPres, sufficient infectivity was generated to kill 100% of inoculated animals (21). However, infectivity and PrPres were not quantitated, and thus contamination was difficult to exclude as an explanation for the results. In contrast, in a modified PMCA system using purified brain PrPsen plus poly(A) RNA in place of crude brain homogenates, Deleault and colleagues detected sufficient amplification of infectivity to rule out contamination (22). However, the infectivity levels found in this system were low compared with the amount of PrPres generated (22), which suggested that much of the PrPres formed in vitro might not be infectious.

In the present experiments we used the original PMCA method (21) that has been used by numerous other researchers. However, we also used end-point dilution titrations in animal bioassays to quantitate the infectivity and analyze the correlation between infectivity and PrPres. As opposed to earlier studies where prion infectivity was often assayed in material from a single round after >15 serial rounds of PMCA (21–24), we analyzed multiple early rounds of several different hamster and transgenic mouse PMCA experiments. Furthermore, to estimate infectivity titers all but one (22) of these earlier studies used an incubation time assay based on a standard curve using brain-derived prion infectivity (25), but such a standard curve may not be valid for PMCA-derived infectivity (26, 27), especially if a new prion strain is generated (28). In contrast, in the present experiments the use of end-point dilution titrations enabled us to follow the disappearance of the input infectivity in control reactions and accurately titer any newly generated infectivity. Here, we show that significant amounts of new prion infectivity were generated within the first four rounds in the PMCA assay. However, the infectivity titer per the amount of PrPres protein (i.e., “specific infectivity”) generated in PMCA reactions was considerably lower than that of brain-derived in vivo infectivity. Thus, there appeared to be an important qualitative difference in the infectivity produced during brain infection in vivo compared with the material produced by PMCA in vitro.

Results

Cell-Free in Vitro Amplification of 263K Scrapie Using Transgenic Mouse Brain Homogenates.

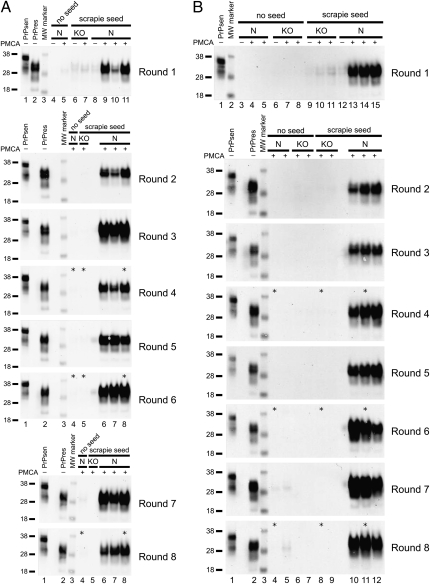

In previous experiments brain homogenates from transgenic mice expressing high levels of PrPsen were more efficient substrates in PMCA reactions than homogenates from mice expressing normal PrP levels (29, 30). Therefore, we established a PMCA reaction using as substrate brain homogenates from tg7 hamster PrP transgenic mice, which express 4- to 5-fold more PrP than hamsters (31). 263K scrapie brain from a terminal stage tg7 mouse containing PrPres was used at a 1:100 dilution to seed the PMCA reaction. Following a round of PMCA (defined in Materials and Methods), the products were diluted 10-fold into another reaction containing new tg7 brain homogenate substrate for an additional round of PMCA. This process of serial PMCA was repeated for eight rounds, and generation of PrPres at high levels was detected at each round in two independent experiments (Fig. 1 A and B). Strong amplification of PrPres was evident when seeded reactions that underwent the first round of PMCA were compared with unsonicated control frozen samples containing the input seed (Fig. 1A, round 1, compare lanes 9–11 with lane 8; and Fig. 1B, round 1, compare lanes 13–15 with lane 12). As a negative control, when PrP knockout (KO) brain homogenate was seeded with 263K scrapie brain and subjected to PMCA, no generation of new PrPres was detected, and only the input PrPres from the seed was seen (Fig. 1 A and B). This control demonstrated the requirement for normal PrPsen as a substrate for these PMCA reactions. Unseeded samples of normal (N) or KO brain homogenate (Fig. 1 A and B) showed no PrPres or infectivity (Table S1). Thus, only reactions containing both 263K scrapie brain PrPres and PrPsen substrates resulted in generation of PrPres in our tg7 PMCA system.

Fig. 1.

Amplification of tg7 hamster PrPres by eight rounds of serial PMCA. (A and B) tg7 experiment 1 (A) and tg7 experiment 2 (B). A 10% brain homogenate from a 263K scrapie-infected tg7 mouse was diluted 10-fold, i.e., 1:100 final brain dilution, into 10% normal brain homogenate from perfused healthy tg7 mice. Following a first round [round 1 (R1)] of PMCA, the sample was diluted 10-fold (5 μL into 45 μL) into 10% tg7 normal brain homogenate for a second round (R2) of PMCA, and this was repeated for eight rounds. After each round 5 μL of each 50-μL PMCA reaction tube was PK digested and analyzed by Western blotting. The PrP substrate in the normal brain homogenate is shown by a non-PK–treated sample, indicated as PrPsen in lane 1 (0.05 mg tissue equivalent), and the seed brain used in these serial PMCA experiments is indicated as PrPres in lane 2 (0.25 mg tissue equivalent). Unseeded reactions of normal tg7 brain homogenate (N), unseeded reactions of PrP knockout mouse brain homogenate (KO), seeded reactions with KO substrate, and seeded reactions with N substrate are indicated. Compared with freeze-control samples that were not subjected to PMCA sonication and incubation (indicated with a “−” sign), products from R1 showed an average amplification of 32- and 12-fold in round 1 of tg7 experiment (expt.) 1 (A) and tg7 expt. 2 (B), respectively. Similar unsonicated freeze controls were done for each round and indicated amplification ranging from 4- to 32-fold in rounds 2–8. A PrPres signal higher than detected in the freeze-control samples is indicative of newly generated PrPres [in R1: (A) compare lane 8 with lanes 9–11 and (B) compare lane 12 with lanes 13–15]. Samples from rounds 7 and 8 in Fig. 1A were run on the same gel and to aid presentation, controls in lanes 1–3 are shown in both round 7 and round 8. Samples used for animal infectivity bioassays are indicated by asterisks. Apparent molecular masses of 18, 28, and 38 kDa are indicated on the left.

Differing Specific Infectivity in PrPres from PMCA vs. tg7 Brain.

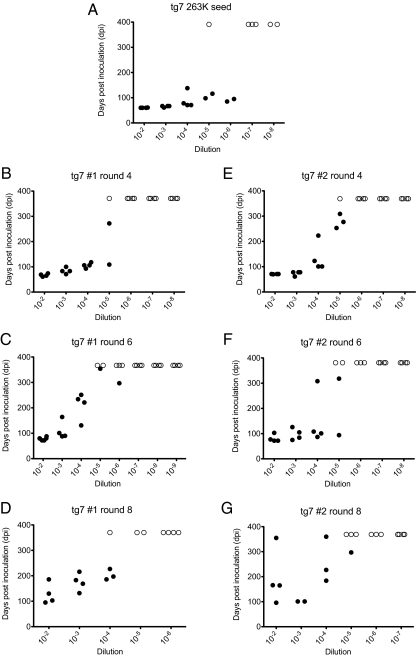

To follow the disappearance of input infectivity and possible PMCA generation of prion infectivity, products of rounds 4, 6, and 8 in the two tg7 PMCA experiments were tested by animal bioassay (Fig. 2). In 263K-seeded PMCA reactions containing normal brain homogenates with PrPsen, infectivity was between 1 and 2 × 105 LD50/50 μL in rounds 4 and 6 of both tg7 PMCA experiments (Table 1). In PMCA round 8 from both tg7 experiments the detected infectivity (2.0–6.3 × 104 LD50/50 μL) was slightly lower than that found in rounds 4 and 6. The infectivity found in the three PMCA rounds appeared to be newly generated infectivity because carryover from the initial seed in control reactions using PrP KO brain homogenates as substrate was only 6.3 × 101 LD50/50 μL in round 4 and was undetectable (<6.3 × 101 LD50/50 μL) in rounds 6 and 8 (Table 1). Thus, the PMCA-generated new infectivity exceeded the carryover in control tubes by >2,500-fold in round 4 products and even more in rounds 6 and 8 where no infectivity was detected in KO controls. Consequently, replication of prion infectivity occurred in our PMCA reactions and required the presence of PrPsen in the substrate.

Fig. 2.

End-point titration of brain-derived and PMCA-generated prion infectivity in tg7 mice. Incubation time is shown on the y axis as days postinoculation (dpi) and 10-fold dilutions of the inoculum are shown on the x axis. Dilutions are shown relative to samples in the PMCA reaction tubes. (A–G) Infectivity data from tg7 mice inoculated with (A) brain-derived tg7 263K scrapie diluted 1:100 in the R1 freeze-control tube as described or (B–G) PMCA products from two separate tg7 PMCA experiments. PMCA products from round 4 (B and E), round 6 (C and F), and round 8 (D and G) were tested. Solid symbols (•) represent animals that died or showed clinical neurological signs. Scrapie was confirmed by detection of PrPres in the brain by Western blot. Open symbols (○) represent animals that did not contract disease. To aid presentation, animals that succumbed to intercurrent death and tested negative for PrPres are not shown.

Table 1.

Comparison of infectivity and PrPres in brain-derived and PMCA-derived materials in PMCA using tg7 brain as substrate

| Material | Substrate* | LD50/50 μL† | Log10LD50/50 μL (±SE) | PrPres/50 μL‡ | Specific infectivity, LD50/PrPres§ | Fold decrease in specific infectivity in PMCA vs. brain¶ |

| Experiment 1 | ||||||

| R1 freeze-control‖ | N | 1.6 × 106 | 6.2 ± 0.26 | 1 | 1.6 × 106 | — |

| R4 PMCA** | KO | 6.3 × 101 | 1.8 ± 0.30 | <0.01 | — | — |

| R6 PMCA | KO | — | — | <0.01 | — | — |

| R4 PMCA** | N | 1.6 × 105 | 5.2 ± 0.27 | 21.0 ± 3.1 | 7.6 × 103†† | 211 |

| R6 PMCA | N | 1.3 × 105 | 5.1 ± 0.35 | 31.9 ± 1.6 | 4.1 × 103†† | 390 |

| R8 PMCA | N | 2.0 × 104 | 4.3 ± 0.20 | 44.4 ± 13.5 | 4.5 × 102†† | 3,560 |

| Experiment 2 | ||||||

| R1 freeze-control‖ | N | 1.6 × 106 | 6.2 ± 0.26 | 1 | 1.6 × 106 | — |

| R4 PMCA** | KO | 6.3 × 101 | 1.8 ± 0.30 | <0.01 | — | — |

| R6 PMCA | KO | — | — | <0.01 | — | — |

| R8 PMCA | KO | — | — | <0.01 | — | — |

| R4 PMCA** | N | 2.0 × 105 | 5.3 ± 0.22 | 14.1 ± 4.3 | 1.4 × 104†† | 114 |

| R6 PMCA | N | 1.0 × 105 | 5.0 ± 0.25 | 24.9 ± 5.2 | 4.0 × 103†† | 400 |

| R8 PMCA | N | 6.3 × 104 | 4.8 ± 0.27 | 36.1 ± 4.2 | 1.8 × 103†† | 889 |

*Ten percent normal tg7 brain homogenates (N) or PrP knockout (KO) mouse brain homogenates were used as substrates for the PMCA reactions.

†Infectivity (LD50) per 50 μL of each PMCA tube was determined by intracerebral inoculation of 50 μL of serial 10-fold dilutions. These data are also shown as the log10 values ± SE in the next column to the right.

‡PrPres detected (mean ± SD) was measured by immunoblotting of twofold dilutions of material tested as shown in Fig. S1. The PrPres found in 50 μL of the tg7 PMCA round 1 freeze control was defined as 1 unit.

§Infectivity (LD50) per amount of PrPres was calculated on the basis of values per 50 μL in PMCA tubes.

¶The fold decrease in specific infectivity of the PMCA-derived material compared with the input brain-derived material.

‖Round 1 (R1) freeze-control and reaction tubes contained 5 μL of 10% tg7 mouse scrapie brain homogenate plus 45 μL of 10% tg7 normal brain homogenate. Control tubes were stored frozen during reactions, whereas reaction tubes were sonicated and incubated for 48 cycles over 24 h per round as described.

**For PMCA rounds 2 and higher, 5 μL from the preceding PMCA round was added as a seed to 45 μL of 10% normal brain homogenate (substrate).

††P < 0.001 compared with R1 freeze control.

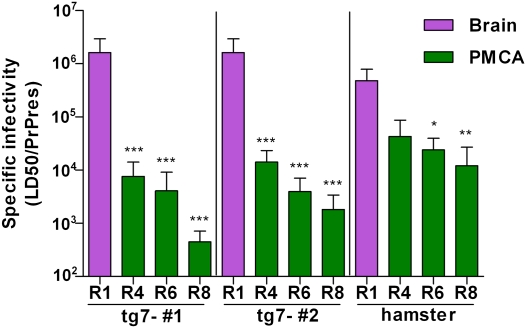

We next determined the specific infectivity of PrPres generated in the PMCA assay, i.e., amount of infectivity per amount of PrPres. Using quantitative immunoblotting the amount of PrPres in the PMCA products was compared with that in the round 1 freeze control tubes, which was defined as 1 PrPres unit. PMCA reaction tubes from rounds 4, 6, and 8 had 14.1–44.4 PrPres units (Table 1 and Fig. S1). To calculate the infectivity per amount of PrPres, the LD50/50 μL was divided by the PrPres/50 μL for each round tested. The specific infectivity for the round 1 brain-derived input seed was 1.6 × 106 LD50/PrPres unit. In contrast, the specific infectivity values for the PMCA products from rounds 4, 6, and 8 were 4.5 × 102–1.4 × 104 LD50/PrPres unit (Table 1). When expressed relative to the input, the specific infectivity of rounds 4, 6, and 8 PMCA products ranged from 114-fold to 3,560-fold lower than the brain-derived input (Table 1). In summary, although abundant prion infectivity was generated in PMCA reactions, specific infectivity of PMCA-generated PrPres was significantly lower than that of brain-derived PrPres.

Similar Diseases Were Induced by Brain-Derived and PMCA-Generated tg7 Prion Infectivity.

Clinical signs and incubation times may vary among different prion strains and can be used to differentiate strains (32). Therefore, we analyzed these properties in animals inoculated with brain-derived and PMCA-derived samples. After inoculation of tg7 mice with round 4 and round 6 PMCA products, the observed clinical signs included hyperactivity, ataxia, kyphosis, somnolence, and weight loss. These signs were indistinguishable from those observed in animals inoculated with brain-derived 263K scrapie agent stocks. However, some tg7 mice inoculated with round 8 products died after showing no clinical signs or only minor wasting, but were nevertheless found positive for PrPres in the brain by postmortem analysis.

Several lines of evidence failed to indicate that there were new scrapie strains generated in the PMCA reactions. First, there were no detectable differences in the glycoform pattern or the band size in the immunoblot profile of the PrPres from animals that succumbed to disease induced by PMCA-generated material compared with PrPres induced by inoculation of scrapie brain (Fig. S2 A and B). Second, tg7 mice inoculated with the 10−2 and 10−3 dilutions of tg7 PMCA products from rounds 4 and 6 presented with short incubation times (Fig. 2 B, C, E, and F), which were similar to those seen in animals inoculated with 10−3 and 10−4 dilutions of the brain-derived 263K seed material in the round 1 freeze control tubes (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were seen between tg7 PMCA-generated and brain-derived material when data were plotted as mean incubation period vs. log10LD50 inoculated (Fig. S3A). These data strengthened the conclusion that new strains were not generated in the PMCA-derived materials from tg7 mice. In summary, neither the clinical disease nor the incubation periods nor the glycoform patterns observed suggested that PMCA-derived infectivity had different strain properties compared with the original brain-derived 263K scrapie stocks used in these experiments.

PMCA Using Hamster Brain PrPsen Substrate.

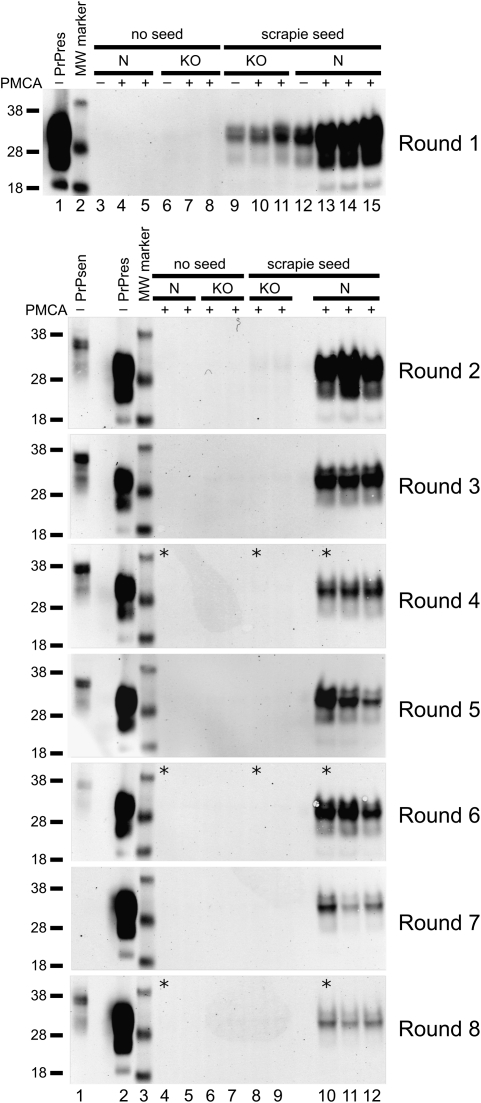

To confirm and extend the results from tg7 PMCA experiments, similar experiments were done using 263K scrapie-infected hamster brain as a PrPres seed at a 1:1,000 dilution and normal hamster brain homogenate containing PrPsen as a substrate. Similar to the tg7 system, generation of new PrPres was detected by the increased amount of PrPres in the PMCA-amplified samples (Fig. 3, lanes 13–15) compared with the unsonicated freeze-control sample (Fig. 3, lane 12) or seeded PrP KO mouse brain samples (Fig. 3, lanes 9–11), which showed only the original input from the seed. Also similar to the tg7 system, unseeded samples of normal brain homogenate (N) and KO brain homogenate subjected to eight rounds of serial PMCA showed no PrPres (Fig. 3, round 1, lanes 3–5 and 6–8; and rounds 2–8, lanes 4–5 and 6–7). Thus, PrPres was generated only by seeded PMCA in Syrian hamster brain homogenates in these experiments.

Fig. 3.

Amplification of Syrian hamster (SHa) PrPres by serial PMCA. A 10% brain homogenate from a 263K scrapie-infected SHa was diluted 100-fold, i.e., 1:1,000 final brain dilution, into 10% normal brain homogenate from perfused healthy SHa. Following a first round of PMCA, the sample was diluted 10-fold into 10% SHa normal brain homogenate for a second round of PMCA. This process of serial PMCA was repeated for a total of eight rounds. A total of 5 μL of each 50-μL PMCA reaction tube was PK digested and then analyzed by Western blotting. The PrP substrate in the normal brain homogenate is shown by a non-PK–treated sample, indicated as PrPsen in lane 1 in rounds 2–8 (0.05 mg tissue equivalent). The seed used in this serial PMCA is indicated as PrPres in lane 1 in round 1 and lane 2 in rounds 2–8 (0.05 mg tissue equivalent). Duplicate unseeded reactions of normal hamster brain homogenate (N) and PrP KO mouse brain homogenate and seeded reactions with KO in duplicate and N in triplicate are indicated. Compared with freeze-control samples that were not subjected to PMCA (indicated with a “−” sign), products from R1 showed a 6-fold amplification. Similar freeze controls were done for each round and indicated an amplification ranging from 3- to 16-fold in rounds 2–8. A PrPres signal higher than detected in the freeze-control samples is indicative of newly generated PrPres (compare lane 12 with lanes 13–15 in R1). Samples used for animal infectivity bioassays are indicated by asterisks. Apparent molecular masses of 18, 28, and 38 kDa are indicated on the left.

Comparison of Infectivity Titers and PrPres Levels in Hamster PMCA and Brain Samples.

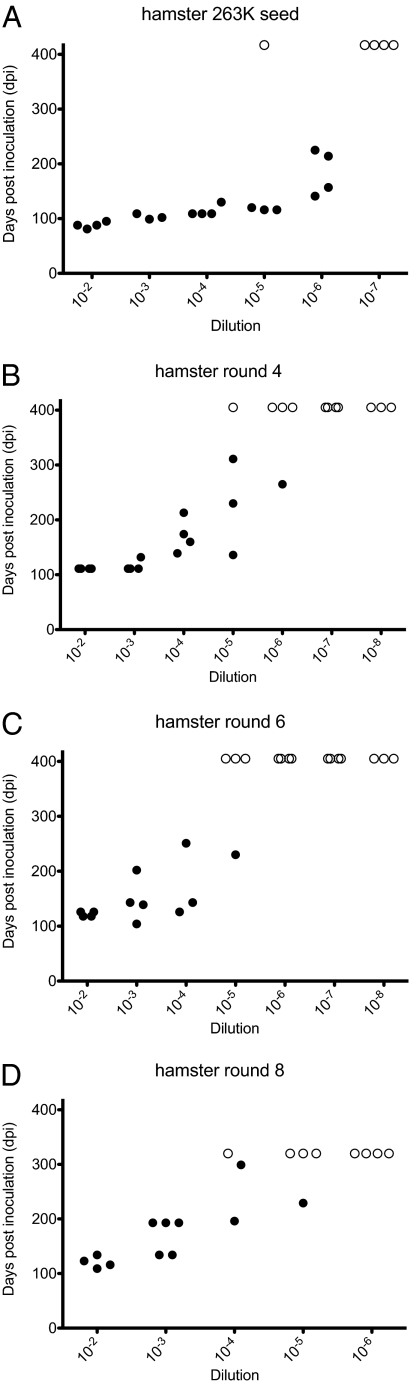

Similar to the results from the tg7 PMCA, the amount of infectivity found in rounds 4 and 6 of the hamster PMCA (3.2 × 105 and 6.3 × 104 LD50/50 μL) (Fig. 4) far exceeded the carryover infectivity from the initial round 1 input seed (1.0 × 103 and 5.0 × 101 LD50/50 μL) detected in reactions using KO brain as substrate (Table 2). One round 8 PMCA product was also titered for infectivity (Fig. 4) and the detected infectivity (2.6 × 104 LD50/50 μL) also exceeded the carryover in round 6 (carryover in round 8 was not measured) (Table 2). Thus, amplification of prion infectivity occurred in cell-free PMCA reactions in the hamster system. No infectivity was detected in unseeded hamster brain homogenates subjected to 4, 6, and 8 rounds of serial PMCA (Table S1).

Fig. 4.

End-point titration of brain-derived and PMCA-generated prion infectivity in hamsters. Incubation time is shown on the y axis as days postinoculation (dpi) and 10-fold dilutions of the inoculum are shown on the x axis. Dilutions are shown relative to samples in the PMCA reaction tubes. Syrian hamsters were inoculated with brain-derived 263K scrapie (A) and PMCA products from round 4 (B), round 6 (C), and round 8 (D). Solid symbols (•) represent animals that died or showed clinical neurological signs. Scrapie was confirmed by detection of PrPres in the brain by Western blot. Open symbols (○) represent animals that did not contract disease. To aid presentation, animals that succumbed to intercurrent death and tested negative for PrPres are not shown.

Table 2.

Comparison of infectivity and PrPres in brain-derived and PMCA-derived materials in PMCA using hamster brain as substrate

| Material | Substrate* | LD50/50 μL† | Log10LD50/50 μL, ± SE | PrPres/50 μL‡ | Specific infectivity, LD50/PrPres§ | Fold decrease in specific infectivity in PMCA vs. brain¶ |

| R1 freeze control‖ | N | 2.0 × 106 | 6.3 ± 0.22 | 4.2 | 4.8 × 105 | — |

| R4 PMCA** | KO | 1.0 × 103 | 3.0 ± 0.30 | <0.04 | — | — |

| R6 PMCA | KO | 5.0 × 101 | 1.7 ± 0.33 | <0.04 | — | — |

| R4 PMCA** | N | 3.2 × 105 | 5.5 ± 0.31 | 7.5 ± 1.8 | 4.3 × 104 | 11 |

| R6 PMCA | N | 6.3 × 104 | 4.8 ± 0.22 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 2.4 × 104†† | 20 |

| R8 PMCA | N | 2.6 × 104 | 4.4 ± 0.34 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.2 × 104‡‡ | 40 |

*Ten percent normal hamster brain homogenates (N) or PrP knockout (KO) mouse brain homogenates were used as substrates for the PMCA reactions.

†Infectivity (LD50) per 50 μL of each PMCA tube was determined by intracerebral inoculation of 50 μL of serial 10-fold dilutions. These data are also shown as the log10 values ± SE in the next column to the right.

‡PrPres detected (mean ± SD) was measured by immunoblotting of twofold dilutions of material tested as shown in Fig. S4A. To be able to compare the amount of PrPres produced in the hamster and tg7 PMCA systems, the fold difference in the amount of PrPres in the 263K tg7 and hamster brain homogenates used as input seed was determined (Fig. S4B) and used to normalize the two systems. The amount of PrPres found in 50 μL of the hamster PMCA round 1 freeze control was 4.2 times that of the tg7 system.

§Infectivity (LD50) per amount of PrPres was calculated on the basis of values per 50 μL in PMCA tubes.

¶The fold decrease in specific infectivity of the PMCA-derived material compared with the input brain-derived material.

‖Round 1 (R1) freeze-control and reaction tubes contained 5 μL of 1% hamster scrapie brain homogenate plus 45 μL of 10% hamster normal brain homogenate. Control tubes were stored frozen during reactions, whereas reaction tubes were sonicated and incubated for 24 h per round as described.

**For PMCA rounds 2 and higher, 5 μL from the preceding PMCA round was added as a seed to 45 μL of 10% normal brain homogenate (substrate).

††P < 0.05 compared with R1 freeze control.

‡‡P < 0.01 compared with R1 freeze control.

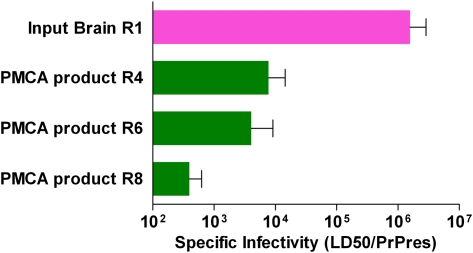

In a similar manner to that in the tg7 PMCA experiments, we quantified the amount of PrPres produced (Fig. S4) to determine the specific infectivity per amount of PrPres in brain-derived round 1 input seed vs. that in PMCA-generated hamster PrPres (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, the specific infectivity of hamster PMCA products from rounds 4, 6, and 8 was 11-, 20-, and 40-fold lower than that of the brain-derived 263K hamster scrapie used in round 1 as input seed. Thus, in both the tg7 system and the Syrian hamster system, PrPres generated in the PMCA was associated with lower levels of infectivity per PrPres compared with brain-derived PrPres (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of specific infectivity (infectivity in LD50/PrPres units) in brain-derived (R1 input) vs. PMCA-derived (output from R4, R6, and R8) materials. Results from two experiments with tg7 brain and one experiment with hamster brain are shown. Infectivity was quantitated in rounds 4, 6, and 8 of the PMCA reaction by in vivo endpoint dilution titration. In all experiments new infectivity was generated during PMCA reactions; however, the specific infectivity was much lower for PMCA-derived material than for brain-derived material. The SEs for the specific infectivity values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Each experiment was analyzed statistically by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, using GraphPad Prism software. P values shown are for comparison of R1 input brain-derived material vs. PMCA-derived material from each round tested: ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Similar Diseases Induced in Hamsters by Brain-Derived and PMCA-Derived Prion Infectivity.

Inoculation of Syrian hamsters with rounds 4, 6, and 8 PMCA products resulted in a fatal neurological disease. The clinical signs observed were similar to those in tg7 mice with the addition of head bobbing, which was not seen in tg7 mice. These signs were indistinguishable from those observed in animals inoculated with brain-derived 263K scrapie agent stocks.

In hamster PMCA products there was no evidence for generation of new scrapie strains. For example, immunoblot analyses of PrPres bands from brains of hamsters receiving brain-derived or PMCA-derived infectivity were not different (Fig. S2C). Incubation periods of similarly titered samples from brain and PMCA gave similar incubation periods (Fig. S3B and Fig. 4A vs. Fig. 4 B–D). The similarities of these days postinoculation (dpi) values suggested that PMCA-generated and brain-derived infectious material did not contain different prion strains.

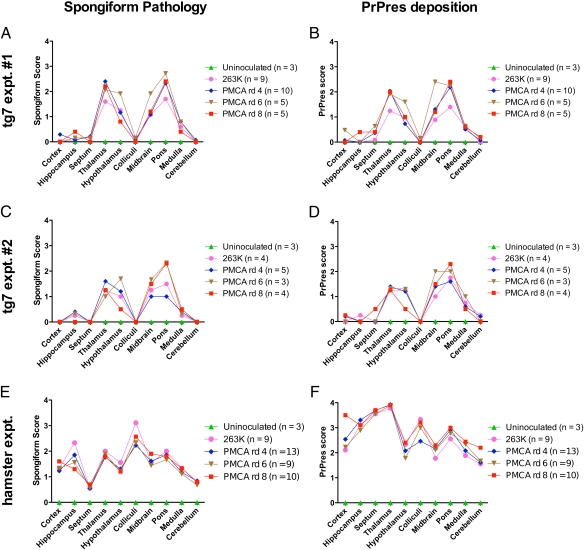

Histopathological Analyses of Animals Inoculated with PMCA- and Brain-Derived Prion Infectivity.

To further characterize the disease induced by PMCA-generated PrPres material in our tg7 and hamster experiments, we performed histopathological analyses of brains from animals that succumbed to infection with PMCA-derived material (Fig. 6). Brains from recipients of PMCA products, as well as positive and negative controls, were scored blinded for spongiform pathology (Fig. 6 A, C, and E) and PrPres deposition (Fig. 6 B, D, and F) in 10 brain regions. No significant differences were observed between the different groups of infected animals (Fig. 6). Furthermore, animals infected with PMCA products giving either long or short incubation periods (Figs. 2 and 4) did not appear to differ in regional pathology. This result supported our earlier observations of the similarities in clinical signs, incubation times, and PrPres immunoblot profile induced by PMCA-produced material compared with those induced by in vivo-generated scrapie agent.

Fig. 6.

Spongiosis and PrPres deposition in brains of animals inoculated with brain-derived or PMCA-generated prion infectivity. Tg7 hamster PrP transgenic mice (A–D) and Syrian hamsters (E and F) inoculated with brain-derived and PMCA-generated prion infectivity were scored for severity of spongiform change (A, C, and E) and amount of PrPres deposition (B, D, and F) in 10 indicated brain areas. Tg7 experiment 1 is shown in A and B, and experiment 2 in C and D. The number of animals scored in each group is indicated in parentheses in the Inset and the scoring procedures are described in Materials and Methods. There was overlap of SD between groups, indicating that there were no statistically significant differences. Therefore, SD bars were omitted as they interfered with the presentation.

Discussion

In the present study, we have used end-point dilutions to titer the prion infectivity in several rounds of multiple independent PMCA experiments. Input seed infectivity was diluted out in early serial PMCA rounds, and newly generated infectivity was detected at levels 320- to 3,200-fold higher than input background by PMCA round 4 and even more by rounds 6 and 8 (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, prion infectivity detected in these PMCA products was not the result of carryover from input seed. In our experiments we detected high titers of infectivity by end-point dilution titration in seeded reactions in multiple serial rounds in several independent experiments but not in control reactions, indicating that contamination was an unlikely explanation. Taken together, these results provided strong evidence that prion infectivity was indeed generated under cell-free conditions in the PMCA assay. Because viruses do not replicate in cell-free conditions, this result is against the concept that the prion infectious agent is a virus.

Some previous studies (21, 24, 33, 34) have attempted to estimate the difference in infectivity for PMCA-generated PrPres compared with brain-derived PrPres. However, in these studies specific infectivity could not be determined because PrPres and/or infectivity were not quantitated by dilution titration. In our present experiments the use of end-point dilution titration of both infectivity and PrPres enabled us to calculate specific infectivity (amount of infectivity per amount of PrPres) for both brain-derived and PMCA-generated PrPres samples. In both animal models used in our study, the specific infectivity associated with PMCA-generated PrPres was markedly lower than that of brain-derived PrPres (Fig. 5 and Tables 1 and 2). These results suggested that possibly only a fraction of PMCA-generated PrPres correlated with infectivity. This conclusion was in agreement with previous results using a modified PMCA system, where 33-fold lower specific infectivity was found for in vitro propagated material vs. brain-derived material (22).

These findings concurred with an earlier proposal that the infectious prion might be a unique conformer of PrPres (PrP*) (35). Thus, the majority of PrPres generated in the PMCA might lack a unique infectious conformation. This might be due to an “off pathway” conversion as previously described by others (18, 36, 37). Alternatively, the majority of PrPres produced in the PMCA might lack an additional non-PrP component needed for infectivity. Therefore, this difference in generation of infectious prions in the PMCA vs. in vivo may be due to differences in cofactor utilization during the conversion process (38). Other recent in vitro experiments support the concept that different PrP conversion pathways can result in differences in both infectivity and in vitro amyloid formation (39). Further evidence for extensive variation in the quantitative correlation between PrPres and infectivity in brain has also been noted previously by others (40, 41). Together all these findings support the conclusion that measurement of PrPres from PMCA or in vivo tissue sources is not a reliable quantitative marker for prion infectivity.

Interestingly, the specific infectivity of PrPres in our round 8 PMCA products was lower than in rounds 4 and 6, which suggested that generation of a noninfectious form of PrPres might be increasing by round 8 (Fig. 5). If this scenario is indeed the case, two outcomes might be envisioned in subsequent rounds: (i) a continued decline of specific infectivity due to competition by the noninfectious pathway or (ii) a maintained level of specific infectivity due to establishment of equilibrium between the different conversion pathways.

Another possible explanation for the lower specific infectivity of PMCA-generated PrPres is that infectious PrPres aggregates might be larger than those produced in vivo. However, this result appears unlikely because the sonication steps in the PMCA procedure are presumed to break up aggregates. Alternatively, Weber and colleagues suggested that PMCA-generated PrPres particles are smaller than brain-derived particles and therefore might be less infectious due to biological clearance (24, 34, 42). However, another report suggested that smaller PrPres particles might be more infectious than larger PrPres aggregates (41). Thus, it remains unclear whether alterations in the size of infectious prion particles could explain the lower specific infectivity of PMCA-generated PrPres.

In previous PMCA studies, the use of brain homogenate substrates with a higher level of PrPsen expression correlated with production of higher amounts of PrPres (29, 30). Similarly, in our PMCA experiments with tg7 brain homogenates, which had PrPsen expression 4- to 5-fold higher than that in hamsters, ∼10-fold more PrPres was generated compared with the hamster system. However, despite this difference in PrPres amount, similar titers of infectivity were produced in the tg7 and hamster PMCA systems (Tables 1 and 2). Perhaps in the tg7 system, exhaustion of a critical cofactor limited the total infectivity generated. Alternatively, the higher level of PrPsen present in the tg7 brain substrate might favor conversion to a noninfectious form of PrPres.

In contrast to PMCA assays using brain-derived PrP as substrate (21, 22), the use of recombinant PrP as a substrate for cell-free generation of PrPres in PMCA (20) or using other methods to induce misfolding (43) has resulted in generation of barely detectable infectivity. However, one study reported prion infectivity from PMCA reactions using recombinant PrP without scrapie brain seed that caused a 100% fatality rate with a short incubation time among inoculated animals (23). Unfortunately, infectivity was not titered in this study, and the inoculum was pooled from 50 reactions, suggesting that the amount of infectivity per reaction might be low. Further studies will be needed to confirm the details of results from this interesting system.

Previous studies have reported that strain-specific properties of the input scrapie seed are maintained under certain PMCA conditions (21, 44). However, under other conditions where higher amounts of input seed and increased cycles per round were used, PMCA conversion even across a resistant species barrier has been reported (28). In our experiments using conditions similar to those previously described (21), no significant differences in clinical signs, incubation periods, and histopathological or biochemical data were found between animals inoculated with brain-derived input seed or PMCA-derived products from rounds 4, 6, and 8. This similarity in biological properties suggested that the infectivity in these samples did not differ in the scrapie strain despite the large differences in infectivity per amount of PrPres that were detected. We speculate that these differences in specific infectivity might be caused by presence in PMCA reactions of an aberrant PrP conversion pathway or lack of required brain-derived cofactors. If so, these same factors did not alter the strain-related properties of the scrapie infectivity produced in these in vitro reactions.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Triton X-100 was from Boehringer Mannheim. EDTA was from Invitrogen. Sodium chloride, sodium deoxycholate, and Tris were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Preparation of Brain Homogenates from Scrapie-Infected and Uninfected Animals.

All animals were housed at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility, and research protocols and experimentation were approved by the National Institutes of Health Rocky Mountain Laboratories Animal Care and Use Committee (permit nos. 2009-21 and 2009-80). This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council. Weanling female Syrian hamsters (SHa) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories. Tg7 transgenic mice were bred at Rocky Mountain Laboratories. Tg7 mice overexpress hamster PrP but do not express mouse PrP and are highly susceptible to infection by 263K hamster scrapie agent (45).

To prepare uninfected brain homogenates for use as substrates in the PMCA reaction uninfected hamsters or tg7 mice were euthanized with isoflurane and perfused with PBS supplemented with 5 mM EDTA before harvesting the tissue, and whole brains were removed and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Brains were weighed and transferred into 2.0-mL microcentrifuge tubes with 1.0-mm glass beads, and a 20% wt/vol homogenate was made using PMCA conversion buffer (21) [PBS supplemented with 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% vol/vol Triton X-100, 4 mM EDTA, and the cOmplete Mini mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)]. Samples were homogenized for 20–30 s in a Mini-Beadbeater-8 machine (Biospec Products), cooled on ice for 2 min, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 s to reduce foaming. This homogenization step was repeated once. Brain homogenates were diluted to 10% wt/vol by adding an equal volume of PMCA conversion buffer and were clarified by centrifuging at 1,500 × g for 30 s at 4 °C. Supernatants were aliquoted into new tubes and stored at −80 °C.

To produce scrapie brain homogenates for PMCA reactions 50 μL of a 1% hamster scrapie brain homogenate from strain 263K was used to inoculate hamsters or tg7 mice expressing hamster PrP, using previously described methods (46). At the time of clinical disease, animals were euthanized with an overdose of isoflurane, but were not perfused. Brain tissues were then processed and stored as described above for uninfected animals.

PMCA Procedure.

For tg7 PMCA experiments, each tube contained a seed of 5 μL of 10% 263K scrapie brain homogenate from infected clinical tg7 mice diluted into 45 μL of 10% normal tg7 brain homogenate (total scrapie brain dilution of 1:100). For Syrian hamster PMCA reactions each tube contained a seed of 5 μL of 1.0% 263K scrapie brain homogenate from infected clinical hamsters diluted into 45 μL of 10% normal hamster brain homogenate (total scrapie brain dilution of 1:1,000). This higher dilution was used because of the higher concentration of PrPres in scrapie brain from hamsters vs. tg7 mice. Negative controls included tubes containing brain homogenate substrate from uninfected PrP knockout mice and also tubes with normal brain homogenates that were not seeded with scrapie brain. Samples were loaded into thin-walled 0.2-mL PCR tube strips with individually attached caps (GENEMATE SnapStrip; BioExpress). Tubes were positioned in a plastic rack (PMCA adapter; Misonix) placed on the rim of a microplate horn of a Misonix Model 3000 microsonicator so that the 50-μL samples were immersed in the water (200 mL) of the sonicator bath. The microplate horn was covered with a plastic lid to minimize evaporation from the water bath. The entire sonicator was located inside an incubator set to 37 °C and was programmed to perform cycles of sonication (40-s pulse at 60% potency) followed by incubation for 30 min. Following each round of PMCA consisting of alternating periods of sonication and incubation for 48 cycles (i.e., 24 h), the product was diluted 10-fold into another reaction containing normal hamster or tg7 brain homogenate for a further round of PMCA. This process of serial PMCA was repeated for a total eight rounds.

Inoculation and Observation of Experimental Animals Used for Infectivity Titrations.

Young adult animals were inoculated with 263K scrapie brain homogenates from tg7 mice or Syrian hamsters or with products from PMCA experiments. PMCA products were diluted at least 100-fold before inoculation to avoid deleterious effects of detergent on animals. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and 50 μL was injected in the left parietal lobe with a 27-gauge, 1/2-inch needle. Animals were observed daily for onset and progression of scrapie and were euthanized when scrapie signs were consistently noted. Brains were removed and divided sagittally, one-half was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C for future use in biochemical analyses, and the other half was immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (3.7% formaldehyde) for histological studies. After confirmation of the detection of PrPres by immunoblot, the time of euthanasia was used as the incubation time shown in Figs. 2 and 4. Inoculated tg7 mice were observed for ≥370 dpi and inoculated hamsters for ≥320 dpi before termination of the experiment. Mean and SE values for prion infectivity titers were calculated using the Spearman–Kärber equations (47). Specific infectivity values were calculated by dividing the infectivity (LD50/50 μL) by the amount of PrPres/50 μL, using a linear scale where the amount of PrPres in the round 1 PMCA tube before amplification, which contained tg7 scrapie brain diluted 1:100 as seed, was designated as 1 unit. Because the error in the infectivity titration was much larger than the error in the PrPres determination, the PrPres error was not used in the calculation of the specific infectivity SE. Instead, the SE value for infectivity (LD50/50 μL) as determined by the Spearman–Kärber method was used as the error for the specific infectivity. Statistical analysis of specific infectivity values was done using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test with GraphPad Prism software.

Infectivity data were also analyzed by plotting incubation period values vs. log10LD50 inoculated for tg7 and hamster recipients of PMCA-generated material and brain-derived material. These data were analyzed statistically by linear regression analyses and 95% confidence intervals were compared for Y-intercept and slope values using GraphPad Prism software.

Immunoblot Analysis of PrP.

To detect PrPres in brain tissues, brain homogenates (20%) were prepared in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), using a Mini-Beadbeater-8 machine (Biospec Products). All homogenates were sonicated for 1 min using a Vibracell cup-horn sonicator (Sonics) and briefly vortexed. PrPres preparation was done as previously described (46). Briefly, an aliquot of a 20% tissue homogenate was adjusted to 100 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.3), 1% Triton X-100, and 1% sodium deoxycholate and treated for 45 min at 37 °C with proteinase K (Roche) at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. The reaction was stopped by adding Pefabloc SC (Roche) to a final concentration of 6 mM and the resulting homogenate was placed on ice for 5 min. An equal volume of 2× Laemmli sample buffer (BioRad) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol was added and samples were frozen at −80 °C until needed. For gels, samples were thawed, boiled 5 min, and electrophoresed on 16% SDS/PAGE gels (Invitrogen). Immunoblots were probed with 3F4 anti-PrP antibody (1:5,000 dilution of concentrated supernatant from 3F4-expressing hybridoma) (48), followed by a peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (NA931; GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL) as directed (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). For PrPsen samples, the proteinase K treatment step was omitted.

To detect PrPres in PMCA samples, 5 μL was removed from each PMCA reaction tube and treated with 50 μg/mL proteinase K for 60 min at 45 °C with continuous shaking at 350 rpm in a Thermomixer R (Eppendorf North America). The reaction was stopped by adding Pefabloc SC to a final concentration of 6 mM and placed on ice for 5 min. Four times NuPAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen), 8 M urea, and 100% β-mercaptoethanol were added to samples to reach final concentrations of 1× NuPAGE sample buffer, 2 M urea, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol and then frozen at −80 °C until needed. When thawed for gels, samples were boiled 5 min and electrophoresed on 10% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gels in Mes buffer (Invitrogen). Gels were transferred to HyBond ECL nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) on an iBlot dry-transfer device (Invitrogen) at the P3 setting for 7 min. Immunoblots were blocked in Near-Infrared Fluorescence Western Blotting Blocking Buffer (Rockland Immunochemicals) and PBS mixed in equal parts. Immunoblots were probed with 3F4 anti-PrP antibody diluted at 1:5,000 in Near-Infrared blocking buffer:TBS with 0.2% Tween (1:1) followed by an IRDye800CW-conjugated goat–anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (LiCor) diluted at 1:10,000 in the above buffer. Bands were detected using an Odyssey near-infrared fluorescence scanner (LiCor).

Neuropathology and Immunohistochemistry.

Tissues were immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (3.7% formaldehyde) for 3–5 d before dehydration and embedding in paraffin. Serial sagittal 5-μm sections were cut using a standard Leica microtome, placed on positively charged glass slides, and dried overnight at 43 °C. Slides were stained with a standard protocol of hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) for observation of overall pathology. Immunohistochemical staining and antigen retrieval for PrP was performed using the Ventana automated Discovery Benchmark XT stainer. PrPres antigens were exposed by incubation in CC1 buffer (Ventana) containing Tris-Borate-EDTA, pH 8.0, for 60 min at 95 °C. Staining for PrP was done using anti-PrP antibody 3F4 (supernatant from 3F4-expressing hybridoma, used neat) at 37 °C for 60 min, followed by a biotinylated anti-mouse IgG antibody (HK3359M; Biogenex) and Streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase with DAB as chromogen (DABMap kit; Ventana). H&E staining and the staining for PrPres were observed using an Olympus BX51 microscope.

Clinical Scoring of Neuropathology.

Clinical scoring of experiments was performed blind on 5-μm sagittal sections stained with hematoxylin/eosin and anti-PrP (3F4), respectively. Sections stained with H&E were scored for the severity of spongiform vacuolar degeneration in 10 standard gray matter areas as previously described (49). Spongiosis was scored as follows: 0, no vacuoles; 1, few vacuoles widely and unevenly distributed; 2, few vacuoles evenly distributed; 3, moderate numbers of vacuoles evenly distributed; and 4, many vacuoles with some confluences. PrPres deposition was scored as follows in the same 10 areas: 0, no deposition; 1, 1–25% of area covered with deposition; 2, 26–50% of area covered with deposition; 3, 51–75% of area covered with deposition; and 4, >76% of area covered with deposition. Group mean scores were plotted against area to give representative lesion profiles and analyzed statistically using Prism 5.0c software (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rebecca Rosenke, Lori Lubke, Nancy Kurtz, Dan Long, and Katie Phillips for technical support. The authors also thank Byron Caughey, Suzette Priola, Andrew Timmes, James Carroll, and James Striebel for critical suggestions about the manuscript and Jeffrey Severson for animal husbandry. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of Intramural Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Author Summary on page 19109.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1111255108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chesebro B. Introduction to the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies or prion diseases. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:1–20. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandner S, et al. Normal host prion protein (PrPC) is required for scrapie spread within the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13148–13151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Büeler H, et al. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell. 1993;73:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohwer RG. The scrapie agent: “a virus by any other name”. In: Chesebro BW, editor. Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies, Scrapie, BSE and Related Disorders, Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 172. New York: Springer; 1991. pp. 195–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith JS. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature. 1967;215:1043–1044. doi: 10.1038/2151043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton DC, McKinley MP, Prusiner SB. Identification of a protein that purifies with the scrapie prion. Science. 1982;218:1309–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.6815801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merz PA, Somerville RA, Wisniewski HM, Iqbal K. Abnormal fibrils from scrapie-infected brain. Acta Neuropathol. 1981;54:63–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00691333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prusiner SB, et al. Scrapie prions aggregate to form amyloid-like birefringent rods. Cell. 1983;35:349–358. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diringer H, et al. Scrapie infectivity, fibrils and low molecular weight protein. Nature. 1983;306:476–478. doi: 10.1038/306476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKinley MP, Bolton DC, Prusiner SB. A protease-resistant protein is a structural component of the scrapie prion. Cell. 1983;35:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesebro B. BSE and prions: Uncertainties about the agent. Science. 1998;279:42–43. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesebro B. Prion protein and the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy diseases. Neuron. 1999;24:503–506. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dormont D. Agents that cause transmissible subacute spongiform encephalopathies. Biomed Pharmacother. 1999;53:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(99)80053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kocisko DA, et al. Cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein. Nature. 1994;370:471–474. doi: 10.1038/370471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saborio GP, Permanne B, Soto C. Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature. 2001;411:810–813. doi: 10.1038/35081095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colby DW, et al. Prion detection by an amyloid seeding assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20914–20919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710152105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atarashi R, et al. Simplified ultrasensitive prion detection by recombinant PrP conversion with shaking. Nat Methods. 2008;5:211–212. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0308-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caughey B, Baron GS, Chesebro B, Jeffrey M. Getting a grip on prions: Oligomers, amyloids, and pathological membrane interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:177–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082907.145410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JI, et al. Mammalian prions generated from bacterially expressed prion protein in the absence of any mammalian cofactors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14083–14087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.113464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castilla J, Saá P, Hetz C, Soto C. In vitro generation of infectious scrapie prions. Cell. 2005;121:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deleault NR, Harris BT, Rees JR, Supattapone S. Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9741–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702662104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang F, Wang X, Yuan CG, Ma J. Generating a prion with bacterially expressed recombinant prion protein. Science. 2010;327:1132–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.1183748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber P, et al. Cell-free formation of misfolded prion protein with authentic prion infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15818–15823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605608103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prusiner SB, et al. Molecular properties, partial purification, and assay by incubation period measurements of the hamster scrapie agent. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4883–4891. doi: 10.1021/bi00562a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prusiner SB, et al. Measurement of the scrapie agent using an incubation time interval assay. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:353–358. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Somerville RA, Carp RI. Altered scrapie infectivity estimates by titration and incubation period in the presence of detergents. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:2045–2050. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-9-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castilla J, et al. Crossing the species barrier by PrP(Sc) replication in vitro generates unique infectious prions. Cell. 2008;134:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurt TD, et al. Efficient in vitro amplification of chronic wasting disease PrPRES. J Virol. 2007;81:9605–9608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyerett C, et al. In vitro strain adaptation of CWD prions by serial protein misfolding cyclic amplification. Virology. 2008;382:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kercher L, Favara C, Chan CC, Race R, Chesebro B. Differences in scrapie-induced pathology of the retina and brain in transgenic mice that express hamster prion protein in neurons, astrocytes, or multiple cell types. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:2055–2067. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63256-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruce ME. TSE strain variation. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:99–108. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green KM, et al. Accelerated high fidelity prion amplification within and across prion species barriers. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000139. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber P, Reznicek L, Mitteregger G, Kretzschmar H, Giese A. Differential effects of prion particle size on infectivity in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:924–928. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissmann C. Spongiform encephalopathies. The prion's progress. Nature. 1991;349:569–571. doi: 10.1038/349569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilham JM, et al. Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.May BC, Govaerts C, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Prions: So many fibers, so little infectivity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deleault NR, Kascsak R, Geoghegan JC, Supattapone S. Species-dependent differences in cofactor utilization for formation of the protease-resistant prion protein in vitro. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3928–3934. doi: 10.1021/bi100370b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piro JR, et al. Seeding specificity and ultrastructural characteristics of infectious recombinant prions. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7111–7116. doi: 10.1021/bi200786p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barron RM, et al. High titers of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy infectivity associated with extremely low levels of PrPSc in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35878–35886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silveira JR, et al. The most infectious prion protein particles. Nature. 2005;437:257–261. doi: 10.1038/nature03989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber P, et al. Generation of genuine prion infectivity by serial PMCA. Vet Microbiol. 2007;123:346–357. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makarava N, et al. Recombinant prion protein induces a new transmissible prion disease in wild-type animals. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castilla J, et al. Cell-free propagation of prion strains. EMBO J. 2008;27:2557–2566. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Race R, Oldstone M, Chesebro B. Entry versus blockade of brain infection following oral or intraperitoneal scrapie administration: Role of prion protein expression in peripheral nerves and spleen. J Virol. 2000;74:828–833. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.828-833.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meade-White K, et al. Resistance to chronic wasting disease in transgenic mice expressing a naturally occurring allelic variant of deer prion protein. J Virol. 2007;81:4533–4539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02762-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dougherty R. Animal virus titration techniques. In: Harris R, editor. Techniques in Experimental Virology. New York: Academic; 1964. pp. 169–224. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kascsak RJ, et al. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol. 1987;61:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meade-White KD, et al. Characteristics of 263K scrapie agent in multiple hamster species. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:207–215. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.081173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]