Abstract

HIV infects and replicates in CD4+ T cells but effects on host immunity and disease also involve depletion, hyper-activation, and modification of CD4-negative cell populations. In particular, the depletion of CD4-negative γδ T cells is common to all HIV+ individuals. We found that soluble or cell-associated envelope glycoproteins from CCR5-tropic strains of HIV could bind, activates the p38-caspase pathway, and induce the death of γδ cells. Envelope binding requires integrin α4β7 and chemokine receptor CCR5 which are at high levels and form a complex on the γδ T cell membrane. This receptor complex facilitated V3 loop binding to CCR5 in the absence of CD4-induced conformational changes. Cell death was increased by antigen stimulation after exposure to envelope glycoprotein. Direct signaling by envelope glycoprotein killed CD4-negative γδ T cells and reproduced a defect observed in all patients with HIV disease.

Introduction

HIV evades the immune response and establishes persistent infection by depleting lymphocyte subsets and altering pathways for cellular maturation or activation.1 CD4+ T cells are targets for productive virus infection which causes cell death.2,3 Other cell subsets can be depleted without productive infection; these include B cells,4 NK cells,5–7 γδ T cells8–11 and uninfected, bystander CD4 T cells.12–14 Loss of uninfected cells is due to indirect effects of HIV which are important mechanisms for immune deficiency and disease leading to AIDS.

Pathogenesis of HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) have been linked to increased apoptosis of uninfected cells. Comparing HIV infection with virulent SIV (rhesus) or nonvirulent SIV (African green macaques) showed that apoptosis in CD4+ T cells was an identifying characteristic of pathogenic infections.15 Sooty mangabeys displayed limited bystander cell killing despite high viremia, consistent with their natural resistance to disease.16,17 Increased levels of Fas18 or PD-119 were associated with cell death or dysfunction. Antibody blocking of Fas ligand20,21 or PD-122 slowed disease by preserving CD4+ central memory or CD8+ CTL, respectively.

The roles for viral proteins in killing of uninfected, bystander cells are poorly understood. Previous studies suggested that HIV encodes several apoptogenic proteins with potential to cause cell death, including envelope, Vpr, Tat, and Nef,23–26 but it is not known whether they are present at sufficient levels in uninfected cells. We do know that envelope is a potent inducer of apoptosis7,13,14,26,27 but it is not clear how the protein binds and signals CD4-negative cells which form a significant proportion of cells lost to indirect effects of HIV. Cell depletion through indirect effects (noninfectious mechanisms) is apparent in the loss of phosphoantigen-responsive Vγ2Vδ2+ T cells (also termed Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells in an alternate nomenclature) that normally comprise 1-4% of circulating lymphocytes and 75% of all circulating γδ T cells in healthy individuals.28,29 HIV-associated loss of Vγ2Vδ2 cells was postulated to involve apoptosis.30 In this study, we found that R5 tropic HIV envelope glycoprotein induced significant death of CD4-negative Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Envelope binding and signaling may be an important mechanism for depleting Vγ2Vδ2 cells during HIV disease.

Methods

PBMC and tumor cell lines

Whole blood was obtained from healthy human volunteers with written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; all protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Total lymphocytes were separated from heparinized peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque; Amersham Biosciences). PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO), 2mMol/L l-glutamine, and penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/mL and 100 mg/mL, respectively). HeLa and 293T cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO), 2mMol/L l-glutamine, and penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/mL and 100 mg/mL, respectively). For HeLa cells expressing an R5 tropic HIV envelope (ADA), methotrexate was added to a final concentration of 2μM.

Reagents

The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV CN54 gp120 from Dr Ian Jones, HIV gp120 MAb 17b, and 48d from Dr James E. Robinson, HIV gp120 MAb 447-52D and 697-30D from Dr Susan Zolla-Pazner, HIV gp120 MAb VRC01 from Dr John Mascola, HIV gp120 MAb 2G12 from Dr Hermann Katinger, HIV gp120 MAb ID6 from Dr Kenneth Ugen and Dr David Weiner, Antiserum to HIV gp120 from Dr Michael Phelan, MAb to CCR5 (2D7 and 45 531) and the CCR5 binding antagonist drug Maraviroc. Recombinant Human MAdCAM-1 Fc Chimera is from R&D Systems (R&D Systems). Other specific molecular antibodies include: β7 MAb FIB27 and FIB504 (Biolegend), α4 MAb HP2/1 (Millipore), CCR5 MAb R-C10 (Biolegend), CCR5 MAb (NT; ProSci), activating Fas Ab (clone CH11; Millipore), blocking Fas Ab (clone ZB4; Millipore). Caspase inhibitors were purchased from BioVision. P38 inhibitor SB203580 was from Cell Signaling Technology.

Generating Vγ2Vδ2 T cell lines

PBMC were cultured with complete medium and stimulated with 15μM isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP; Sigma-Aldrich) plus 100 U/mL human recombinant IL2 (Tecin, Biologic Resources Branch, National Institutes of Health). Fresh medium and 100 U/mL IL2 were added every 3 days. In some experiments, retinoic acid was added at 10 ng/mL. γδ T cell proliferation was measured by staining for CD3 and Vδ2, and then determining the percentage of γδ T cells within the total lymphocyte population at 14 days after stimulation. Cell lines obtained after in vitro expansion, were purified further by negative selection with a human γδ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell death assays

293T cells were transiently transfected with Fugene (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and empty vector or plasmids expressing the envelope cDNA of HIV R5 strains BaL, SF162, JRFL, ADA, or YU2 (provided by Dr Joseph Sodroski, Department of Immunology and Infectious Disease, Harvard School of Public Health). After 48 hours, transfected 293T cells were harvested and resuspended with purified (> 97%) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells at 105 293T cells:2 × 105 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, and then plated in triplicate on 96-well plates for 24 hours. To document envelope expression, transfected 293T cells were lysed, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and immunoblotted with polyclonal antiserum specific for HIV gp120 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Program). For soluble gp120, BaL (kindly provided by Dr Tim Fouts, Protectus Biosciences) or CN54 gp120 proteins (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Program) were added to 2 × 105 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells at various concentrations in 96-well plates for 24 hours; all tests were done in triplicate and replicated for multiple, unrelated PBMC donors. For blocking studies against α4β7 or CCR5, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with blocking reagents or antibodies for 1 hour at 37°C before adding to the killing assay. For inhibition studies with anti-gp120 antibodies, gp120 were reacted with specific antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then the mixture was added to target cells for cytotoxicity assays. Caspases involved in cell killing were identified with specific inhibitors; Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with caspase inhibitors for 1 hour 37°C before the killing assay. The percentage of cell mortality was calculated using Trypan blue dye exclusion as follows: 1 – (total number of cells viable on day 2/total number of cells viable on day 1 immediately after stimulation) × 100. Cell death was confirmed in each experiment with flow cytometry-based methods based on gating for Vδ2+ cells then determining the intensity of annexin V and 7AAD staining.

Confocal microscopy

Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were surface stained with the β7 mAb FITC and CCR5 mAb PE, or the Vγ2Vδ2 mAb PE and gp120 FITC. Stained cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and mounted on slides with prolong gold (Invitrogen). Cells were imaged with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. Representative confocal images were processed and cropped using LSM Image Browser (Zeiss).

Coprecipitation

Purified Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (2 × 107) were washed, resuspended in PBS, and then treated for 30 minutes with or without 2mM DTSSP (Pierce Biotechnology) at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 20mM Tris, pH 7.5; cells were lysed in a Pierce IP Lysis Buffer (Pierce Biotechnology). Lysates were incubated with either anti-β7 mAb FIB27 or rat IgG2a as indicated, then precipitated with Protein G magnetic beads (New England Biolabs). Precipitated proteins were electrophoresed on reducing SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted.

Immunoblot analysis

Samples were boiled for 10 minutes, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with various primary antibodies. Secondary antibodies including HRP-conjugated, anti-rabbit, anti-rat, or anti-mouse (Cell Signaling Technology), were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

gp120 binding to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells

To analyze binding of gp120 to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, cells were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated rgp120 (Immuno Diagnostic) in staining buffer HBS (HEPES buffered saline) or RPMI 1640 at room temperature for 2 hours, and then washed once in staining buffer. For α4β7 or CCR5 blocking studies, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with blocking reagents or antibodies for 1 hour at 37°C before staining. For inhibition studies with anti-gp120 antibodies, gp120 were pre-incubated with specific antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then the mixture was added to target cells for staining.

Flow cytometry

Unless noted, cells were stained with fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies from BD Biosciences. Generally, 3-5 × 105 cells were washed, resuspended in 50-100 μL of RPMI 1640, and stained with mouse anti–human Vδ2 (PE or FITC) clone B6, mouse anti-human CD3 (APC) clone UCHT1, rat anti–human β7 (FITC) clone FIB504, mouse anti–human α4 (PE) clone 9F10, mouse anti–human CD206 (PE) clone 15–2, mouse anti–human CD209 (APC) clone Dcn-46, mouse anti–human CCR5-(PE) clone 3a9, and isotype controls, including mouse IgG1-FITC clone X40, IgG1-PE clone X40, IgG1-APC clone X40, and rat IgG2a FITC. Cells were stained with annexin V PE and 7AAD in annexin V binding buffer. Cells were washed with staining buffer and resuspended. Data for at least 1 × 104 lymphocytes (gated on the basis of forward-scatter and side-scatter profiles) were acquired from each sample on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). All samples were analyzed using FlowJo 8.8.2 software (TreeStar). For stimulation before staining, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were treated with IPP for 4 hours at 37°C.

Statistical analysis

Differences among groups were analyzed by Student t test. P < .05 was considered to be significant.

Results

HIV R5-tropic envelope glycoprotein induces Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death

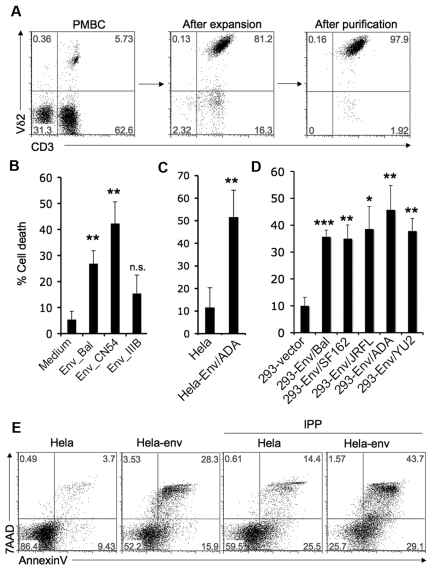

We hypothesized that HIV envelope might play an important role in Vγ2Vδ2 T cell depletion. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were expanded from healthy donor PBMC after stimulating with isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) plus IL-2 for 14 days and purified by negative selection (Figure 1A). Purified Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were treated with 2 soluble R5-tropic HIV gp120 proteins from the BaL or CN54 HIV strains, and X4-tropic HIV gp120 from the IIIB strain, at 10 μg/mL for 24 hours. Cell death was evaluated by counting trypan blue dye negative cells; results were confirmed with flow cytometry for annexin V and 7AAD staining on the Vδ2+ population (Figure 1B, supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site, see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). R5-tropic HIV gp120 proteins from BaL or CN54 induced significant T cell death. The IIIB- gp120 caused less T cell death than either of the R5 envelopes. CN54-gp120 killed Vγ2Vδ2 cells at concentrations as low as 50 ng/mL (supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1.

HIV R5-tropic envelope glycoprotein induces Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death. (A) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were expanded from healthy donor PBMC after stimulating with isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP, 15μM) plus IL-2 (100U/mL) for 14 days, and then purified by negative selection to ≥ 97% purity. (B-D) Cell death was evaluated after Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with soluble HIV gp120 proteins (BaL, CN54 or IIIB; 10 μg/mL) (A), HeLa cells or HeLa cells expressing HIV ADA-envelope (B), 293 cells transfected with empty vector or 293 cells expressing R5-tropic envelopes (BaL, SF162, JRFL, ADA, or YU2) (C) for 24 hours as described in “Methods.” Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (error bars, SD). The statistical significance compared with control was analyzed (*P < .05, **P < .005, ***P < .0001; Student t test). (E) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were treated with HeLa cells or HeLa cells expressing HIV ADA-envelope for 24 hours and then stimulated with the TCR ligand IPP (15μM) for 4 hours. Cells were stained with annexin V and 7AAD. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

We next tested the effect of cell-associated HIV (R5-tropic) envelope glycoproteins. Cell lines (HeLa or 293) expressing HIV envelope were mixed for 24 hours in a ratio of 1:2 with purified Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. A stable HeLa cell line expressing HIV envelope from the ADA strain induced significant Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death compared with HeLa cell control (Figure 1C, supplemental Figure 3). Transiently transfected 293T cell lines expressing HIV R5 envelope from either of 5 HIV strains, (BaL, SF162, JRFL, ADA, and YU2; supplemental Figure 4) also caused significant Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death (Figure 1D, supplemental Figure 5).

Increased cell division and death rates in HIV infection are probably a reflection of persistent immune activation.1,12 Activation-induced cell death (AICD), implying a role for TCR-dependent antigen recognition, has been proposed to explain cell loss and might be an important mechanism for Vγ2Vδ2 T cell depletion. We tested the effects of HIV envelope on AICD. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were treated with HeLa cells or HeLa cells expressing HIV envelope (ADA) for 24 hours, and then stimulated with the TCR ligand isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP). Prior exposure to HIV envelope followed by antigen stimulation, sensitized Vγ2Vδ2 T cells to AICD (Figure 1E).

Very high levels of α4β7 and CCR5 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells

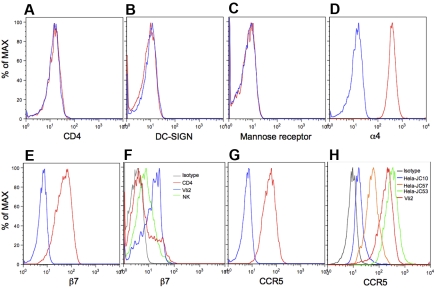

The mechanisms for binding R5-tropic envelope glycoprotein to CD4-negative Vγ2Vδ2 T cells was unknown before this study. A variety of gp120 receptors and coreceptors have been reported, including CD4, DC-SIGN,31,32 Mannose receptor,32–34 α4β7,35,36 and CCR5.37,38 We examined expression levels of these receptors by flow cytometry with gating on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells did not express CD4 (Figure 2A), DC-SIGN (Figure 2B), or Mannose receptor (Figure 2C), but were strongly positive for α4 (Figure 2D), β7 (Figure 2E), and CCR5 (Figure 2G).39–41 A majority of lymphocytes and monocytes expressed similar levels of α4 (supplemental Figure 6), but Vγ2Vδ2 T cells expressed β7 at levels much higher than most CD4 or NK cells (Figure 2F, supplemental Figure 7). High expression of CCR5 is also a feature of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.39 We determined the density of CCR5 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by comparing with standard cell lines. Surface CCR5 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells was present at more than 50 000 receptor/cell (Figure 2H, supplemental Figure 8). In contrast, CCR5 levels on CD4 T cells ranged from 2000 to 10 000 molecules/cell.42 Thus, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells have exceptionally high expression of 2 receptors for gp120, α4β7 and CCR5, despite being negative for CD4. A fraction of CD4 T cells (Figure 2F) also expressed these high levels of β7.36

Figure 2.

Very high levels of α4β7 and CCR5 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were stained with specific antibodies to CD4 (A), DC-SIGN (B), Mannose receptor (C), α4 (D), β7 (E), or CCR5 (G red lines), or isotype controls (blue lines), and analyzed with flow cytometry. (F) Expression of β7 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (blue line), CD4 T cells (red line), and NK cells (green line) was analyzed with flow cytometry. (H) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells and 3 standard HeLa cell lines various in the level of cell-surface CCR5 (JC10, JC57 and JC53) were stained with CCR5-PE and isotype control, and then analyzed with flow cytometry. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

HIV envelope-induced killing of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells depends on α4β7 and CCR5

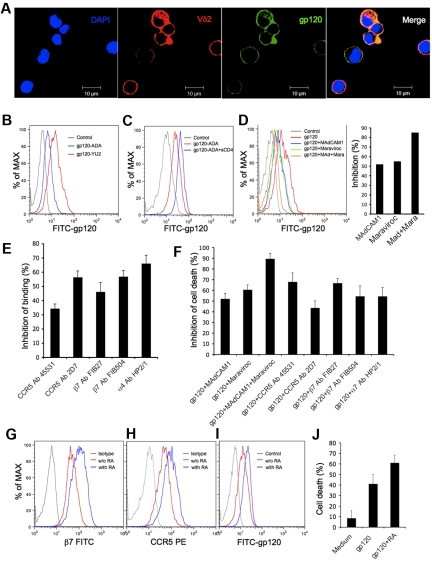

gp120 binding to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells was tested with fluorescein-conjugated R5 tropic gp120 from ADA and YU2 strains. In the absence of divalent cations, which are necessary for full activity of α4β7,35 gp120 binds poorly to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells; treating with Ca2+ or Mn2+ enhanced gp120 binding (supplemental Figure 9). To be consistent with cell toxicity assays, we then used culture medium for binding assays, which contains Ca2+ and Mg2+ but we did not supplement divalent cations above their normal levels in medium. These conditions allowed us to detect the binding of gp120 from ADA and YU2 strains to Vγ2Vδ2 T cell surfaces using confocal microscopy (Figure 3A) and flow cytometry (Figure 3B). YU2-gp120 showed higher binding affinity in these assays than did ADA-gp120 (Figure 3B). Consistent with previous reports,43,44 soluble CD4 increased the gp120 binding to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Figure 3C) but there was already substantial binding in the absence of CD4.

Figure 3.

HIV envelope-induced killing of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells depends on α4β7 and CCR5. (A-B) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were stained with fluoresceine conjugated HIV gp120 (green) and Vδ2 mAb (red) and viewed under a confocal microscope (A) or analyzed with flow cytometry (B). (C) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were stained with the fluorescein-conjugated HIV gp120 in the absence or presence of soluble CD4, and then analyzed with flow cytometry. (D) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with Maraviroc (1μM), MAdCAM1 (20 μg/mL), or both for 1 hour before staining with HIV gp120. (E) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with specific antibodies against CCR5, β7 or α4 (20 μg/mL) for 30 minutes before staining with HIV gp120. (F) Cell death was evaluated after Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with soluble HIV gp120 protein (CN54, 10 μg/mL) in the absence or presence of blocking reagents for α4β7 and CCR5. (G-J) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were cultured in the absence or presence of retinoic acid. The expression of β7 (G) and CCR5 (H), the binding of gp120 (I), and gp120-induced cell death (J) were examined as previously described. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (error bars, SD).

To determine whether gp120 binds to both α4β7 and CCR5, we performed blocking studies. The adhesion molecule MAdCAM1 was used to block α4β735 and the binding antagonist Maraviroc was used to block CCR5.45 Individually, MAdCAM1 or Maraviroc partially blocked gp120 (YU2) binding to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Figure 3D). When used together, binding was inhibited by 85% (Figure 3D). Antibodies against α4β7 or CCR5 varied in their capacity to block gp120 binding to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Figure 3E). MAdCAM1 binding α4β7 or Maraviroc binding CCR5 inhibited cell death; when used together, cell death was inhibited by 90% (Figure 3F, supplemental Figures 10-11). Specific antibodies against α4, β7 or CCR5 also inhibited gp120-induced cell death (Figure 3F, supplemental Figure 10). Thus, the maximum γδ T cell death inducible by HIV R5 tropic gp120 depended on binding to α4β7 and CCR5.

Retinoic acid treatment can be used to increase expression of α4β735,46 and CD4-independent binding of gp120 to T cells.35 We showed that retinoic acid elevated α4β7 expression on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Figure 3G). Surprisingly, retinoic acid also increased CCR5 levels (Figure 3H) leading to higher gp120 binding (Figure 3I) and gp120-induced Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death (Figure 3J). These results support our conclusion that gp120-induced Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death depends on α4β7 and CCR5, which together bind gp120 efficiently in the absence of CD4. High levels of both molecules on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells explains their susceptibility to gp120-induced killing.

α4β7 and CCR5 form complexes on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in the absence of CD4

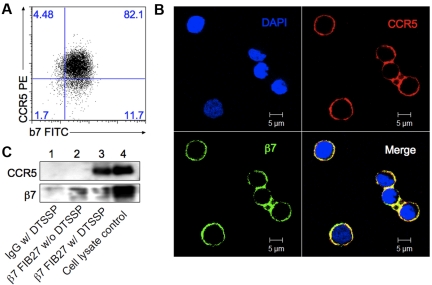

It was reported that CD4 forms complexes with both CCR546 and α4β7.36 Vγ2Vδ2 T cells express high levels of both α4β7 and CCR5, but lack expression of CD4 (Figure 2). We wondered whether α4β7 and CCR5 formed complexes on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Flow cytometry (Figure 4A) and confocal microscopy (Figure 4B) revealed the colocalization of α4β7 and CCR5 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Figure 4B). We did not find significant coimmunoprecipitation of β7 with CCR5 when using an anti-β7 mAb (Figure 4C lane 2) until we used a cross-linking reagent with a spacer arm of approximately 1.2 nm, DTSSP (3,3′-Dithiobis [sulfosuccinimidylpropionate]). After cross-linking, CCR5 could be coimmunoprecipitated with β7 (Figure 4C lane 3), indicating that these 2 receptors exist in close physical proximity on the Vγ2Vδ2 cell membrane.

Figure 4.

α4β7 and CCR5 form complexes on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (A) Flow cytometry assay for expression of CCR5 and β7 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. (B) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were stained with β7 mAb (green) and CCR5 mAb (red), and viewed under a confocal microscope. Yellow in the merged panel represents the colocalization of CCR5 and β7. (C) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were treated or not with the crosslinking reagent DTSSP followed by coprecipitation with protein G magnetic beads and the rat IgG2a+DTSSP (lane 1), β7 mAb FIB27 (lane 2), β7 mAb FIB27 + DTSSP (lane 3). Cell lysates were run as a positive control (lane 4). CCR5 and β7 were detected by Western blot with specific antibodies. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

gp120 V2 and V3 loops mediate binding to Vγ2Vδ2 cells

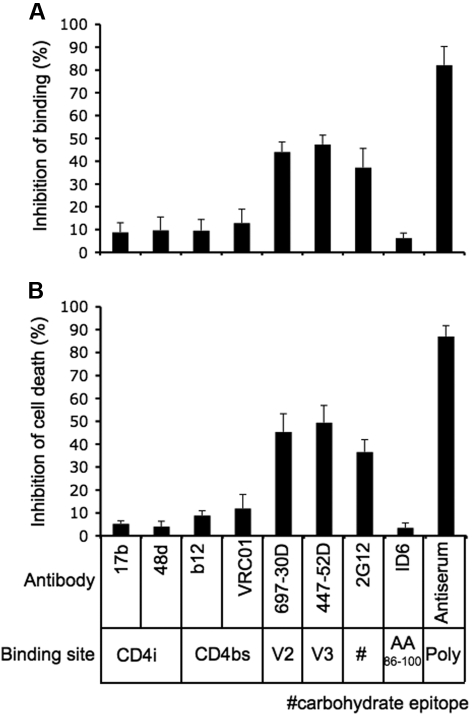

We had established that gp120 from R5-tropic HIV strains induced γδ T cell death by binding to α4β7 and CCR5 in the absence of CD4. To define gp120 structures required for this interaction, we used well-characterized monoclonal antibodies to block binding to γδ T cells. Antibody concentrations were optimized by titering and testing for maximum inhibition of Env binding. First, we tested antibodies 17b and 48d which recognize epitopes exposed after conformational changes because of gp120 engagement with CD4. Neither 17b nor 48d significantly reduced gp120 binding to γδ T cells, although adding sCD4 (Figure 3C) increased gp120-ADA binding. Next, we tested 2 potent neutralizing antibodies, b12 and VRC01, which recognize epitopes overlapping the CD4 binding site (CD4bs); they did not block binding or cell killing. Antibodies 697-30D and 447-52D, which recognize gp120 V2 and V3 loops, respectively, inhibited both gp120 binding and cell death. The interaction of gp120 with Vγ2Vδ2 T cells was also inhibited by neutralizing antibody 2G12, which recognizes a high mannose carbohydrate cluster. The nonneutralizing antibody ID6 showed no inhibition of gp120-Vγ2Vδ2 cell interactions, although a polyclonal sheep antiserum against gp120 blocked most of the binding and γδ T cell killing (Figure 5A-B, supplemental Figure 12). Because V2 and V3 loops direct binding to α4β735 and CCR543,44 respectively, these results support our view that α4β7 and CCR5 are the major targets for HIV envelope on γδ T cells and that prior binding to CD4 is not required for these interactions. Transient exposure of the V2 and V3 loop sequences may facilitate gp120 binding, which would have greater avidity because of high receptor density on γδ T cells.

Figure 5.

gp120 V2 and V3 loops mediate binding to Vγ2Vδ2 cells. (A-B) Fluorescein-conjugated HIV gp120/YU2 (A) or CN54 gp120 (B) was pre-incubated with specific antibodies against (20 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then the mixtures were added to Vγ2Vδ2 T cells for staining (A) or cell killing assays (B). Inhibition of binding or cell death was calculated in relation to gp120 killing or binding is relative to gp120 in the absence of added antibodies. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (error bars, SD).

gp120-induced Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death depends on a p38-caspase pathway

We next sought to define signaling pathways involved in gp120-mediated and α4β7/CCR5-dependent Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death. It has been reported that R5 HIV envelope causes a caspase 8-dependent death of CD4 T cells.13,14 However, RANTES, the natural ligand for CCR5, triggered killing by cytosolic release of cytochrome c, activation of caspases-9 and 3, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage.47 In our system, the broad caspase inhibitor Z-VAD completely blocked gp120-induced cell death (Figure 6A). Caspase-8 inhibitor (Z-IETD) showed significant inhibition of gp120-induced Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death, whereas inhibitors of caspase-2 (Z-VDVAD) and caspase-9 (Z-LEHD) partially inhibited cell death. Inhibitors of caspases 1, 3, or 6 had no effect on cell killing. Consistent with the inhibition experiments, we found that gp120 binding induced the activation (cleavage) of caspase 2, 8, and 9 (Figure 6B). We did not observe down-regulation of several antiapoptotic proteins, including FLIP, Bcl-2, and Bcl-Xl and we showed that gp120 binding did not affect their levels (Figure 6B). Surprisingly, the activation of caspases by gp120 in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells is Fas-independent. First, a Fas neutralizing antibody did not inhibit gp120-induced cell death, although it blocked activating Fas antibody-induced cell apoptosis (supplemental Figure 13A). Second, gp120 did not change the expression of Fas and FasL on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (supplemental Figure 13B).

Figure 6.

gp120-induced Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death depends on p38-caspase pathway. (A) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were untreated or pretreated with specific caspase inhibitors (2μM) for 1 hour at 37°C before incubated with CN54 gp120 (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours. (B) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were incubated with or without Bal or CN54 gp120 protein for 10 hours. Cells were then collected for Western blot assay with specific antibodies. (C) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were untreated or pretreated with specific inhibitors for 1 hour at 37°C before incubating with CN54 gp120 for 24 hours. (D) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were untreated or pretreated with SB203580 or ZVAD for 1 hour at 37°C before incubated with CN54 gp120 for 10 hours. Cells were collected for Western blot assay with specific antibodies. Inhibition of cell death was calculated in relation to gp120-induced cell death with untreated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments (error bars, SD).

Fas-independent caspase activation has been reported previously. In many cases, it depends on the activation of p38 MAPK.48,49 HIV gp120 induces p38-dependent primary CD4 T cell death and neurotoxicity by binding to CXCR4 or CCR5.50,51 We wanted to know whether HIV Env-mediated caspase activation and cell death of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells depended on p38 signaling. p38 inhibitor (SB203580) blocked most of Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death (80%) caused by HIV Env (Figure 6C). As a control, inhibition of Akt (LY294002) increased Env-mediated cell death (Figure 6C), which is consistent with its antiapoptotic role as previously reported.52 Inhibiting other signaling pathways, including Erk (U0126), Ca2+ (CsA), or NFκB, had no significant effect on HIV Env-mediated Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death (Figure 6C). Further, p38 inhibitor blocked both p38 and caspase activation, whereas caspase inhibitor did not block p38 activation (Figure 6D). These findings suggest a novel model for the regulation of caspase during HIV Env-induced Vγ2Vδ2 T cell death based on the sequential activation of p38 MAPK and caspase.

Discussion

R5-tropic HIV envelope binding to α4β7 and CCR5 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells activates caspases 2, 8, and 9 and causes cell death. Exposure to envelope glycoprotein followed by antigen stimulation, increased cell killing consistent with an activation-induced cell death (AICD) mechanism. High levels of CCR5 (> 50 000 receptors/cell) and α4β7 on Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, and close physical proximity of these receptors increases gp120 binding, p38 signaling, and caspase activation. Envelope glycoprotein binding did not require CD4 for efficient interaction with high levels of CCR5, even though CD4 binding is required normally to induce conformational changes which promote CCR5 ligation when chemokine receptor is less abundant on the cell surface.43,44

Indirect cell killing and a role for AICD have been postulated to explain part of the CD4 T cell loss in HIV disease.12 We propose that envelope-mediated signaling is also responsible for the extensive loss of CD4-negative Vγ2Vδ2 T cells which has been observed in all patients with HIV disease. The complex TCR repertoire of CD4 T cell populations and the potential for direct killing by productive infection makes it difficult to determine the proportion of these cells lost because of indirect effects. Unique features of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells help to show why indirect killing might be responsible for dramatic depletion of this subset that is observed in all patients with HIV disease. γδ T cells in healthy adults comprise 1-4% of circulating lymphocytes and > 75% express the Vγ2-Jγ1.2 rearranged chain which responds to phosphoantigen.53 When cells are preconditioned by exposure to envelope glycoprotein before triggering with phosphoantigen, which stimulates most cells in the population, the antigen-responsive cells are killed. A uniform response to antigen leads to a uniform cell depletion and loss of an important, innate-like T-cell subset.

Depletion mechanisms for NKT cells,54 particularly ones with the invariant TCRα chain, may be similar to the γδ example but their situation is confused by the overlap of direct and indirect cell killing in these cells which are frequently CD4+. The reported impact of gp120 binding to α4β7 on NK cells7,35 is more similar to what we have described. CD4+ αβ T cells may also be depleted by toxic effects of gp120 in the absence of infection, but the complex T-cell receptor repertoire means that individual antigens will drive depletion of only a small fraction of cells and would be difficult to detect although this mechanism could eliminate antigen-specific subpopulations. These indirect effects of HIV may have a cumulative impact on the CD4+ T cell repertoire, but would not be immediately obvious as for the example of Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell depletion.

We know that Vγ2Vδ2 T cells play critical roles in viral immunity, control of opportunistic pathogens and resistance to malignant disease.55 In advanced HIV disease, Vγ2Vδ2 T are depleted extensively and not recovered during 2-3 years of antiretroviral therapy with complete virus suppression.29 Normal levels of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were observed among natural virus suppressors, consistent with their disease-free status.56 The predominant mechanism for HIV immunodeficiency is loss of CD4+ T cells and their functions. Degrading other compartments of immunity through indirect effects of HIV, broadens and deepens the immune defect. Future directions may explore combinations of agents which block α4β7 and CCR5 binding as a means of reducing HIV replication and preventing loss of critically important, CD4-negative cell subsets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joseph Sodroski, Ian Jones, James E. Robinson, Susan Zolla-Pazner, John Mascola, Hermann Katinger, Kenneth Ugen, David Weiner, Michael Phelan, and the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, for providing antibody reagents used in this study. They appreciate helpful discussions with Maria Salvato, Robert Redfield, Robert Gallo, and Alonso Heredia. They thank Bing Mei for excellent technical assistance and Dr Huiqing Li for imaging experiments.

The studies were supported by US Public Health Service grants CA142458, CA113261, and AI068508 (C.D.P.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.D.P. and H.L. designed research; H.L. performed research; and C.D.P. and H.L. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: C. David Pauza, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 725 W Lombard St, N546, Baltimore, MD, 21201; e-mail: cdpauza@ihv.umaryland.edu.

References

- 1.Moir S, Chun TW, Fauci AS. Pathogenic mechanisms of HIV disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:223–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, et al. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1148–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattapallil JJ, Douek DC, Hill B, Nishimura Y, Martin M, Roederer M. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature03501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moir S, Fauci AS. B cells in HIV infection and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(4):235–245. doi: 10.1038/nri2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nair MP, Schwartz SA. Inhibition of natural killer cell activities from normal donors and AIDS patients by envelope peptides from human immunodeficiency virus type I. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1997;43(7):969–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peruzzi M, Azzari C, Rossi ME, De Martino M, Vierucci A. Inhibition of natural killer cell cytotoxicity and interferon gamma production by the envelope protein of HIV and prevention by vasoactive intestinal peptide. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16(11):1067–1073. doi: 10.1089/08892220050075336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kottilil S, Shin K, Jackson JO, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in HIV infection: effect of HIV envelope-NK cell interactions. J Immunol. 2006;176(2):1107–1114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Peng H, Ma P, et al. Association between Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells and disease progression after infection with closely related strains of HIV in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(9):1466–1472. doi: 10.1086/587107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Autran B, Triebel F, Katlama C, Rozenbaum W, Hercend T, Debre P. T cell receptor gamma/delta+ lymphocyte subsets during HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75(2):206–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poccia F, Boullier S, Lecoeur H, et al. Peripheral V gamma 9/V delta 2 T cell deletion and anergy to nonpeptidic mycobacterial antigens in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected persons. J Immunol. 1996;157(1):449–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace M, Scharko AM, Pauza CD, et al. Functional gamma delta T-lymphocyte defect associated with human immunodeficiency virus infections. Mol Med. 1997;3(1):60–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazenberg MD, Hamann D, Schuitemaker H, Miedema F. T cell depletion in HIV-1 infection: how CD4+ T cells go out of stock. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(4):285–289. doi: 10.1038/79724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlahakis SR, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Bou G, et al. Chemokine-receptor activation by env determines the mechanism of death in HIV-infected and uninfected T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(2):207–215. doi: 10.1172/JCI11109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Algeciras-Schimnich A, Vlahakis SR, Villasis-Keever A, et al. CCR5 mediates Fas- and caspase-8 dependent apoptosis of both uninfected and HIV infected primary human CD4 T cells. AIDS. 2002;16(11):1467–1478. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estaquier J, Idziorek T, de Bels F, et al. Programmed cell death and AIDS: significance of T-cell apoptosis in pathogenic and nonpathogenic primate lentiviral infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(20):9431–9435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meythaler M, Martinot A, Wang Z, et al. Differential CD4+ T-lymphocyte apoptosis and bystander T-cell activation in rhesus macaques and sooty mangabeys during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83(2):572–583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvestri G, Sodora DL, Koup RA, et al. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 2003;18(3):441–452. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iida T, Igarashi T, Ichimura H, et al. Fas antigen expression and apoptosis of lymphocytes in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus strain mac. Arch Virol. 1998;143(4):717–729. doi: 10.1007/s007050050325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velu V, Kannanganat S, Ibegbu C, et al. Elevated expression levels of inhibitory receptor programmed death 1 on simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8 T cells during chronic infection but not after vaccination. J Virol. 2007;81(11):5819–5828. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00024-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poonia B, Pauza CD, Salvato MS. Role of the Fas/FasL pathway in HIV or SIV disease. Retrovirology. 2009;6:91. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvato MS, Yin CC, Yagita H, et al. Attenuated disease in SIV-infected macaques treated with a monoclonal antibody against FasL. Clin Dev Immunol. 2007;2007:93462. doi: 10.1155/2007/93462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velu V, Titanji K, Zhu B, et al. Enhancing SIV-specific immunity in vivo by PD-1 blockade. Nature. 2009;458(7235):206–210. doi: 10.1038/nature07662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badley AD, Pilon AA, Landay A, Lynch DH. Mechanisms of HIV-associated lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood. 2000;96(9):2951–2964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gougeon ML. Apoptosis as an HIV strategy to escape immune attack. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(5):392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fauci AS. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature. 1996;384(6609):529–534. doi: 10.1038/384529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perfettini JL, Castedo M, Roumier T, et al. Mechanisms of apoptosis induction by the HIV-1 envelope. Cell Death Differ. 2005;(12) suppl 1:916–923. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sodroski J, Goh WC, Rosen C, Campbell K, Haseltine WA. Role of the HTLV-III/LAV envelope in syncytium formation and cytopathicity. Nature. 1986;322(6078):470–474. doi: 10.1038/322470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enders PJ, Yin C, Martini F, et al. HIV-mediated gammadelta T cell depletion is specific for Vgamma2+ cells expressing the Jgamma1.2 segment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19(1):21–29. doi: 10.1089/08892220360473934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hebbeler AM, Propp N, Cairo C, et al. Failure to restore the Vgamma2-Jgamma1.2 repertoire in HIV-infected men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Clin Immunol. 2008;128(3):349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chia WK, Freedman J, Li X, Salit I, Kardish M, Read SE. Programmed cell death induced by HIV type 1 antigen stimulation is associated with a decrease in cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in advanced HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11(2):249–256. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, et al. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100(5):587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turville SG, Arthos J, Donald KM, et al. HIV gp120 receptors on human dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98(8):2482–2488. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Liu H, Kim BO, et al. CD4-independent infection of astrocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: requirement for the human mannose receptor. J Virol. 2004;78(8):4120–4133. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4120-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardona-Maya W, Lopez-Herrera A, Velilla-Hernandez P, Rugeles MT, Cadavid AP. The role of mannose receptor on HIV-1 entry into human spermatozoa. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2006;55(4):241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arthos J, Cicala C, Martinelli E, et al. HIV-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin alpha4beta7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(3):301–309. doi: 10.1038/ni1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cicala C, Martinelli E, McNally JP, et al. The integrin alpha4beta7 forms a complex with cell-surface CD4 and defines a T-cell subset that is highly susceptible to infection by HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(49):20877–20882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911796106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272(5263):872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, et al. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381(6584):667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glatzel A, Wesch D, Schiemann F, Brandt E, Janssen O, Kabelitz D. Patterns of chemokine receptor expression on peripheral blood gamma delta T lymphocytes: strong expression of CCR5 is a selective feature of V delta 2/V gamma 9 gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(10):4920–4929. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Pauza CD. Rapamycin increases the yield and effector function of human gammadelta T cells stimulated in vitro. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 60(3):361–370. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0945-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braun RK, Sterner-Kock A, Kilshaw PJ, Ferrick DA, Giri SN. Integrin alpha E beta 7 expression on BAL CD4+, CD8+, and gamma delta T-cells in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mouse. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(4):673–679. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09040673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heredia A, Gilliam B, DeVico A, et al. CCR5 density levels on primary CD4 T cells impact the replication and Enfuvirtide susceptibility of R5 HIV-1. AIDS. 2007;21(10):1317–13. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32815278ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu L, Gerard NP, Wyatt R, et al. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384(6605):179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, et al. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384(6605):184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biswas P, Tambussi G, Lazzarin A. Access denied? The status of co-receptor inhibition to counter HIV entry. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8(7):923–933. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.7.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21(4):527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murooka TT, Wong MM, Rahbar R, Majchrzak-Kita B, Proudfoot AE, Fish EN. CCL5-CCR5-mediated apoptosis in T cells: requirement for glycosaminoglycan binding and CCL5 aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(35):25184–25194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi WS, Eom DS, Han BS, et al. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK induced by oxidative stress is linked to activation of both caspase-8- and 9-mediated apoptotic pathways in dopaminergic neurons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(19):20451–20460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrantz N, Bourgeade MF, Mouhamad S, Leca G, Sharma S, Vazquez A. p38-mediated regulation of an Fas-associated death domain protein-independent pathway leading to caspase-8 activation during TGFbeta-induced apoptosis in human Burkitt lymphoma B cells BL41. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(10):3139–3151. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trushin SA, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Vlahakis SR, et al. Glycoprotein 120 binding to CXCR4 causes p38-dependent primary T cell death that is facilitated by, but does not require cell-associated CD4. J Immunol. 2007;178(8):4846–4853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaul M, Ma Q, Medders KE, Desai MK, Lipton SA. HIV-1 coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 both mediate neuronal cell death but CCR5 paradoxically can also contribute to protection. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(2):296–305. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vlahakis SR, Villasis-Keever A, Gomez T, Vanegas M, Vlahakis N, Paya CV. G protein-coupled chemokine receptors induce both survival and apoptotic signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5546–5554. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parker CM, Groh V, Band H, et al. Evidence for extrathymic changes in the T cell receptor gamma/delta repertoire. J Exp Med. 1990;171(5):1597–1612. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li D, Xu XN. NKT cells in HIV-1 infection. Cell Res. 2008;18(8):817–822. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pauza CD, Riedel DJ, Gilliam BL, Redfield RR. Targeting gammadelta T cells for immunotherapy of HIV disease. Future Virol. 2011;6(1):73–84. doi: 10.2217/FVL.10.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riedel DJ, Sajadi MM, Armstrong CL, et al. Natural viral suppressors of HIV-1 have a unique capacity to maintain gammadelta T cells. AIDS. 2009;23(15):1955–1964. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ff1ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.