Abstract

Despite encouraging results using lymphocyte function antigen-1 (LFA-1) blockade to inhibit BM and solid organ transplantation rejection in nonhuman primates and humans, the precise mechanisms underlying its therapeutic potential are still poorly understood. Using a fully allogeneic murine transplantation model, we assessed the relative distribution of total lymphocyte subsets in untreated versus anti–LFA-1–treated animals. Our results demonstrated a striking loss of naive T cells from peripheral lymph nodes, a concomitant gain in blood after LFA-1 blockade, and a shift in phenotype of the cells remaining in the node to a CD62LloCD44hi profile. We determined that this change was due to a specific enrichment of activated, graft-specific effectors in the peripheral lymph nodes of anti–LFA-1–treated mice compared with untreated controls, and not to a direct effect of anti–LFA-1 on CD62L expression. LFA-1 blockade also resulted in a dramatic increase in the frequency of CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in graft-draining nodes. Our results suggest that the differential impact of LFA-1 blockade on the distribution of naive versus effector and regulatory T cells may underlie its ability to inhibit alloreactive T-cell responses after transplantation.

Introduction

Naive T cells become optimally activated via signaling through Ag-specific TCRs and ligation of costimulatory molecules,1 leading to subsequent proliferation and differentiation. Inhibition of costimulatory pathways is a clinically relevant strategy to inhibiting Ag-specific T-cell responses in transplantation, GVHD, and autoimmunity, resulting in the prolongation of graft survival or a reduction in autoimmune disease.2 Several biologic therapies have been developed in an effort to modulate costimulation, including CTLA-4 Ig, which competes with CD28 for binding to CD80/86, thus attenuating CD28-mediated costimulation to T cells.3,4 In murine models of transplantation, treatment with CTLA-4 Ig resulted in the long-term survival of BM, islet, cardiac, and renal allografts5–7; however, it failed to significantly prolong allograft survival in nonhuman primates when used as a monotherapy.8,9 In recent clinical trials using a regimen including belatacept, a second-generation CTLA-4 Ig molecule, patients demonstrated significantly reduced incidence of nonimmune toxicities associated with calcineurin inhibitor-based regimens, including nephrotoxicity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular events, but also exhibited increased incidence and severity of acute rejection episodes.10 Therefore, additional biologic reagents that could reduce the incidence of rejections might provide a clinically attractive, calcineurin inhibitor–free immunosuppressive regimen for the inhibition of donor-reactive T-cell responses during transplantation.

Lymphocyte function antigen-1 (LFA-1) is an integrin expressed on the surface of T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and neutrophils,11,12 and binds to ICAM-1, ICAM-2, ICAM-3, and JAM-1.13 The LFA-1:ICAM interaction is known to play a crucial role in leukocyte binding and trafficking14 and in greatly increasing the avidity of the T cell:APC interaction at the level of the immunologic synapse,15 and therefore is crucial for the activation of T cells.16 LFA-1 is implicated in transendothelial migration of T cells from the blood into the lymph nodes (LNs) via a sequence of rolling, arrest after LFA-1 activation by ligation of chemokine receptors, firm adhesion, and diapedesis.17–19 In addition, studies have shown that the LFA-1:ICAM interaction is important for T-cell proliferation and cytokine synthesis,20,21 and that LFA-1 stimulation lowers the activation threshold of the T cell to permit both differentiation and activation.22

Given its critical role in T-cell activation and trafficking, the LFA-1:ICAM interaction is an attractive target for therapeutic blockade in the treatment of autoimmunity, transplantation rejection, and GVHD. A humanized anti–LFA-1 mAb, efalizumab, has been developed for use in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.23,24 Despite the clinical efficacy of this drug, the precise mechanisms underlying its therapeutic potential are still poorly understood. Therefore, understanding the efficacy and mechanisms of LFA-1 blockade is of paramount importance to provide the experimental foundation for the translation of this therapeutic finding into clinical use. Previous studies in experimental models of both BM and solid organ transplantation have demonstrated variable results using anti–LFA-1 mAbs, both alone and in combination with other reagents.25–31 Anti–LFA-1 synergized with CTLA-4 Ig in increasing survival and reducing the severity of GVHD after murine BM transplantation.32 Anti–LFA-1 also resulted in significant prolongation in graft survival in a fully allogeneic model of cardiac transplantation in nonhuman primates.33 More recently, in combination with either rapamycin or belatacept, anti–LFA-1 conferred allo-islet graft prolongation in nonhuman primates,34 and pilot studies in human allo-islet transplantation recipients have revealed that LFA-1 blockade (with efalizumab) was effective as part of an immunosuppressive regimen to prevent acute rejection in these patients.35,36

Based on these encouraging results in nonhuman primate models and early studies in humans, we explored the mechanisms by which LFA-1 blockade results in prolongation in graft survival in a murine model. We assessed the relative distribution of total lymphocyte subsets in untreated versus anti–LFA-1–treated animals after transplantation, and importantly, specifically assessed the trafficking and effector function of graft-specific T cells using a transgenic model system. Our results demonstrated a striking loss of naive T cells from the peripheral LNs after LFA-1 blockade and a relative enrichment of activated, graft-specific effectors and CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in graft-draining LNs after LFA-1 blockade. The resulting increase in Treg:effector T cell (Treg:Teff) ratio led to decreased Teff function and increased T-cell apoptosis, thus diminishing the graft-specific T-cell response and prolonging graft survival. Our results suggest that the differential impact of LFA-1 blockade on naive T cells compared with Teffs and Tregs underlies its ability to inhibit graft rejection after transplantation.

Methods

Mice

Six- to 8-week-old adult male C57BL/6 mice and 6- to 8-week-old adult female BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. TCR-transgenic OT-I and OT-II mice were purchased from Taconic and bred onto Thy 1.1+ backgrounds. Act-mOVA mice were kindly provided by Dr M. Jenkins (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) and bred in-house. Animals received humane care and treatment in accordance with Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines, and the study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Skin grafting and administration of anti–LFA-1 and anti–CTLA-4 Igs

Full-thickness skin grafts (∼ 1 cm2) from the dorsal ears or tails of donor mice were transplanted onto the dorsal thorax of the recipient mouse and secured with a plastic adhesive bandage for 5-6 days. Graft survival was monitored by daily inspection, and rejection was defined as the complete loss of viable epidermal tissue. Where indicated, animals received treatment with 500 μg of human CTLA-4 Ig (Bristol-Meyers Squibb) or 250 μg of rat anti–mouse anti–LFA-1 (mCD11a, M17/4; Bioexpress) on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after transplantation.

Flow cytometric analysis for Ag-specific T-cell frequency, absolute number, and FoxP3 expression

Mice were killed, and their spleens and axillary and brachial LNs (total of 4) were collected. Tissues and blood were processed for flow cytometry using standard techniques, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. Cells were stained with anti–CD4-PE, anti–CD8-Pacific Orange, anti–CD44-APC, anti–CD69-FITC (all BD Pharmingen), anti–CD62L-PE/Cy7 (BioLegend), and anti–CD43-PE (eBioscience) in BD TruCount tubes. For FoxP3 expression, cells were stained with anti–CD4-Pacific Blue, anti–CD25-APC, and anti–FoxP3-PE (all BD Pharmingen) and processed using the FoxP3 intracellular staining kit (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on an LSR II multicolor flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo Version 8.1 software (TreeStar).

In vitro T-cell stimulation

OT-I and OT-II T cells were stimulated with ovalbumin (OVA) peptide (10nM OVA 257-264 or 10μM OVA 323-339, respectively) at 3 × 106 cells/well in a 24-well plate in the presence or absence of anti–LFA-1 (100 μg/mL). The culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Mediatech), 2mM l-glutamine, 0.01M HEPES buffer, 100 μg/mL of gentamycin (Mediatech), and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were harvested at the indicated times, stained with anti–CD62L PE, anti–CD43-FITC (anti–1B11-FITC), and anti–CD69 APC (all BD Pharmingen), and analyzed by flow cytometry. For apoptosis experiments, in vitro cultures were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

T-cell adoptive transfer

Splenocytes from OT-I TCR transgenic mice (Thy 1.1+) were prepared and counted, and the frequency of OT-I T cells in the suspension were determined before adoptive transfer. Mice received a single IV injection of 5 × 106 OT-I T cells in 500 μL of PBS. Mice were killed 9 days after transplantation, and axillary and brachial draining LNs were harvested.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Single-cell suspensions of draining LNs from C57BL/6 mice that had been previously skin grafted with BALB/c donor skin were prepared and incubated in a 96-well flat-bottom plate (106 cells/well) along with irradiated BALB/c stimulators (National Cancer Institute mice) and 10 μg/mL of brefeldin A (GolgiPlug; BD Biosciences) for 4 hours. Cells were processed using an intracellular staining kit (BD Biosciences) and stained with anti–TNF-PE and anti–IFN-γ-APC (both BD Pharmingen), anti–CD8-Pacific Orange (Caltag Laboratories), anti–CD4-Pacific Blue, and anti–H2Kd-FITC (Pharmingen). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on an LSR II multicolor flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo Version 8.1 software (TreeStar).

Ex vivo annexin V staining

Single-cell suspensions of OT-I TCR-transgenic T cells from the spleens of OT-I × Thy1.1+ mice were prepared. Mice received a single IV injection of 5 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-I T cells, along with syngeneic B6 carrier splenocytes. The following day, mice received full-thickness dorsal ear and tail skin grafts. Where indicated, recipients of skin grafts received 250 μg of anti–LFA-1 IP on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 after transplantation. Mice were killed 9 days after transplantation and axillary and brachial draining LNs were harvested. Lymphocytes (5 × 105) were resuspended in 100 μL of 1× annexin V binding buffer (BD Biosciences) and stained with annexin V APC (BD Pharmingen). Cells were then blocked with Fc block (clone 2.4G2) and stained with Thy1.1 PerCP and CD8α Pacific Blue (BD Pharmingen).

Statistical analysis

Graft survival was plotted on Kaplan-Meier survival curves and compared by long-rank test. Differences in T-cell frequencies, absolute numbers, surface molecule expression, frequency of cytokine-producing cells, and frequency of apoptotic cells were compared using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. Significance was defined as P < .05. Statistical analysis was done using Prism Version 4 software (GraphPad).

Results

Blockade of LFA-1 results in selective loss of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from peripheral LNs

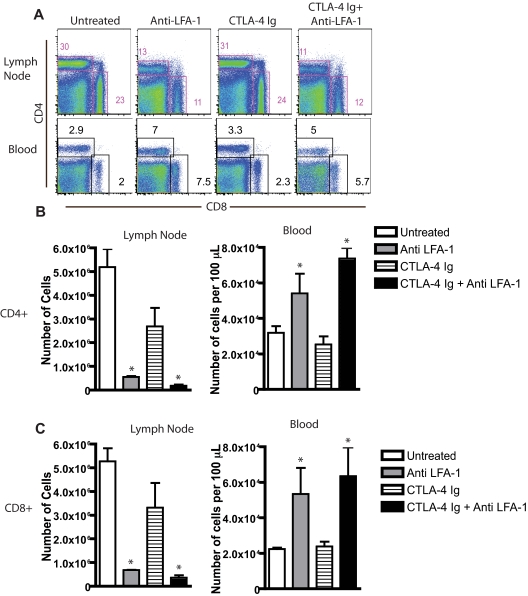

As discussed in the Introduction, blockade of the LFA-1 pathway has been shown to synergize with blockade of the CD28 pathway in experimental models of BM and solid organ transplantation30,32 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). To determine the mechanisms by which LFA-1 blockade might impair alloreactive immune responses in vivo, we analyzed the LN and blood cellular composition before and after inhibition of LFA-1/ICAM interactions during transplantation (Figure 1A). B6 mice received skin grafts from fully allogeneic BALB/c donors. On day 9, mice were killed and draining axillary and brachial LNs were harvested and processed for flow cytometric analysis. Compared with untreated mice, both the frequencies (Figure 1B) and absolute numbers of CD8+ (Figure 1B) and CD4+ (Figure 1C) T cells present in draining LNs in anti–LFA-1–treated mice were significantly reduced (P < .0001). Because LFA-1 antagonism functioned to prolong graft survival only when combined with CTLA-4 Ig, we next investigated whether LFA-1–mediated reductions in the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in draining LNs were also observed in the presence of CTLA-4 Ig. Our data demonstrated that this effect was also observed in mice treated with anti–LFA-1 in combination with CTLA-4 Ig. In contrast, mice treated with CTLA-4 Ig alone did not exhibit a reduction in peripheral LN T-cell frequency or absolute number compared with controls (Figure 1). This effect was T-cell specific, because no differences in the frequencies or absolute numbers of B cells (B220+) macrophages (CD11b+), or dendritic cells (CD11c+) were observed in anti–LFA-1–treated animals (data not shown). Furthermore, the effect of LFA-1 blockade in reducing T-cell frequencies in peripheral LNs was not because of gross depletion of the cells, because analysis of peripheral blood revealed a T-cell lymphocytosis in anti–LFA-1–treated mice (Figure 1A-C). Similarly, no differences were observed in frequencies of splenic T cells in anti–LFA-1–treated mice (supplemental Figure 2). Interestingly, a similar reduction in the frequency and absolute number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was also observed in nondraining LNs of mice not receiving a skin transplantation (P < .0001, supplemental Figure 2). These results suggest that blockade of the LFA-1 pathway results in a reorganization of the peripheral T-cell compartment in an Ag-independent manner, resulting in a selective reduction of T cells from both draining and nondraining peripheral LNs and a concomitant increase in peripheral blood.

Figure 1.

LFA-1 blockade results in selective loss of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from peripheral LNs. (A) B6 recipients of BALB/c SG were left untreated or treated with anti–LFA-1 or CTLA-4 Ig alone or a combination of anti–LFA-1 plus CTLA-4 Ig, and graft-draining LNs were isolated 9 days after skin graft. Cells were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are gated on lymphocytes and are representative examples from 3 experiments with 3 animals per group. (B-C) Treatment with anti–LFA-1, alone or in combination with CTLA-4 Ig, decreases the absolute number of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (C) T cells within peripheral LNs (P < .0001 compared with untreated controls) and increases the absolute number of CD4+ (B) and CD8+ (C) T cells in the peripheral blood (P < .05 compared with untreated controls). Summary plots are shown, representing cumulative numbers from 2 independent experiments and 6 mice per group per time point.

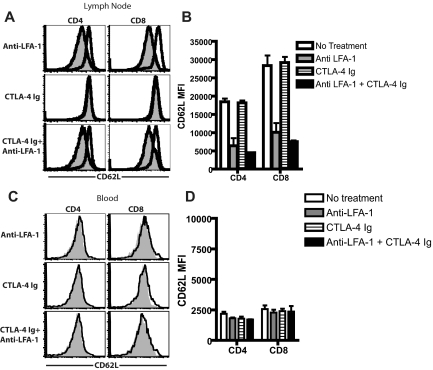

LFA-1 blockade results in decreased CD62L expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral LNs

Based on these data demonstrating that blockade of the LFA-1 pathway resulted in a dearth of T cells in peripheral LNs, we hypothesized that this relative reduction could be because of an alteration in the phenotype of T cells such that their trafficking properties were influenced. In assessing the phenotypes of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in draining LNs of skin-grafted mice, we observed a prominent reduction in the expression of CD62L in mice that were treated with anti–LFA-1 (Figure 2A). Compared with mice that received no treatment or treatment with CTLA-4 Ig alone, mice that received anti–LFA-1 alone or in combination with CTLA-4 Ig exhibited significantly reduced CD62L expression in both the CD4+ and CD8+ populations (P < .0001 compared with untreated, Figure 2B). This reduction in CD62L expression was not observed on either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood (Figure 2B and D), demonstrating that the effect of LFA-1 antagonism on CD62L expression was not a global effect on all T cells in the treated animals. However, decreased CD62L expression in both the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell compartments was observed in both the nondraining LNs and spleens of anti–LFA-1–treated animals (P < .0001, supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, LFA-1 antagonism functions in vivo to decrease CD62L expression on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in secondary lymphoid organs in an Ag-independent manner.

Figure 2.

LFA-1 blockade results in decreased CD62L expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in peripheral LNs. B6 recipients of BALB/c SG were left untreated or treated with anti–LFA-1 alone, CTLA-4 Ig alone, or a combination of anti–LFA-1 plus CTLA-4 Ig, and graft-draining LNs and peripheral blood were collected 9 days after skin grafting. Cells were stained anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-CD62L, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A,C) Open histograms indicate untreated controls; shaded histogram indictes treated animals. Data shown are gated on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in draining LNs (A-B) and peripheral blood (C-D) and are representative examples from 4 experiments with 3 animals per group. (B) Summary data of MFI of CD62L expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from LNs (B) or peripheral blood (D) on day 9 after transplantation. Results showed a statistically significant decrease in CD62L expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the LNs both in the presence and absence of CTLA-4 Ig (P < .0001 compared with untreated controls). Combined data from 2 independent experiments with a total of 6 mice per group are shown.

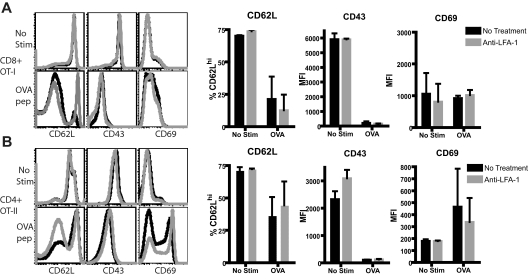

LFA-1 blockade does not act directly to induce CD62L down-regulation

Given the observed changes in cell-surface expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in mice treated with LFA-1 blockade, we sought to determine whether inhibition of LFA-1 signaling acted directly on T cells to reduce CD62L expression. We used a TCR-transgenic system wherein CD8+ OT-I and CD4+ T cells were stimulated in vitro with peptide Ag in the presence or absence of anti–LFA-1. We observed no statistically significant differences in the expression of CD62L, or in the additional markers of activation CD43 or CD69, in the anti–LFA-1–treated cultures compared with untreated cultures (Figure 3; P > .05 for all markers). This was true for both CD8+ (Figure 3A) and CD4+ (Figure 3C) T cells both in the absence or presence of peptide Ag. Therefore, we conclude that inhibition of LFA-1 signaling did not directly affect regulation of the molecules CD62L, CD43, or CD69.

Figure 3.

LFA-1 blockade does not act directly to induce CD62L down-regulation. CD8+ OT-I and CD4+ OT-II T cells were stimulated in vitro with cognate Ag as described in “Methods,” or were left unstimulated and analyzed by flow cytometry 72 hours later. Anti–LFA-1 treatment of unstimulated CD8+ (A) or CD4+ (B) T cells did not result in down-regulation of CD62L or CD43 or change the expression of CD69. Similarly, anti–LFA-1 treatment did not affect the expression of these molecules on peptide-stimulated CD8+ (A) or CD4+ (B) T cells. Flow cytometric plots shown are gated on either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells as indicated and are representative data of 3 independent experiments. Summary graphs are cumulative results from 3 independent experiments and P > .05 comparing anti–LFA-1–treated samples with untreated controls.

Activated lymphocytes are preferentially sequestered in Ag-exposed, anti–LFA-1–treated LNs

Our experiments demonstrated that CD62L was down-regulated on T cells remaining in peripheral LNs after treatment with anti–LFA-1, but that LFA-1 blockade did not directly result in CD62L down-regulation. Therefore, we hypothesized that activated Teffs might be selectively retained in the LNs in anti–LFA-1–treated mice, whereas naive T cells were not, resulting in an increase in the frequency of CD62Llo cells. To test this, a transgenic mouse model was used in which activated donor-reactive T cells could be identified and tracked during the course of graft rejection and distinguished from non-graft-reactive naive T cells. Specifically, B6 mice were adoptively transferred with Thy1.1+ OT-I T cells; animals then received OVA-expressing skin grafts that present the epitope recognized by OT-I T cells and were treated with anti–LFA-1. Analysis of the draining LNs on day 10 after transplantation revealed that activated, Ag-specific Thy 1.1+ CD8+ T cells were present at much higher frequencies in the draining LNs of anti–LFA-1–treated mice compared with untreated controls (Figure 4A-B). This observed increase in the frequency of Thy1.1+ T cells was specific for activated effectors, as the frequency of endogenous, non-graft-specific Thy1.2+CD8+ T cells was significantly diminished, rather than increased, in anti–LFA-1–treated animals (Figure 4F). We further examined the activation phenotypes of both graft-specific Thy1.1+ cells and non-graft-specific Thy1.2+ cells in mice receiving an mOVA skin graft. These data showed that whereas the expression of CD43, CD69, and CD44 was unchanged in the presence of anti–LFA-1 in both groups (Figure 4C-E,G, and H and supplemental Figure 4), CD62L expression was significantly down-regulated on both Ag-specific and non-specific T cells in the presence of LFA-1 antagonism (P < .0001 for both populations compared with untreated controls). These data therefore further confirm that the impact of LFA-1 antagonism on CD62L expression is an Ag-independent effect.

Figure 4.

Activated lymphocytes are preferentially sequestered in Ag-exposed, anti–LFA-1–treated LNs. mOVA graft–specific OT-I T cells were adoptively transferred into B6 recipients; 48 hours later, mice received an mOVA skin graft and were left untreated or were treated with anti–LFA-1. Draining LNs were harvested on day 10 after transplantation and donor-reactive Thy1.1+ T cells and non-donor-reactive endogenous Thy1.2+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A-B) LNs isolated from anti–LFA-1–treated animals demonstrated a greater percentage of Ag-specific, Thy 1.1+ CD8+ T cells compared with LNs isolated from untreated control animals (P = .018). (C-E) Down-regulation of CD62L expression on Thy1.1+ graft–specific T cells was observed after treatment with anti–LFA-1 compared with untreated controls (P < .0001), but there was no difference in the expression of CD43, CD69, and CD44 on these cells. (F) Analysis of endogenous, non-Ag-specific Thy1.2+ CD8+ T cells revealed a reduction in the frequency of cells compared with untreated controls (P = .023). (G-H) Thy1.2+ cells also exhibited decreased expression of CD62L expression (P < .0001) compared with untreated controls. Data shown are either representative (flow plots) or cumulative (bar graphs) from 2 independent experiments with a total of 8-9 mice per group.

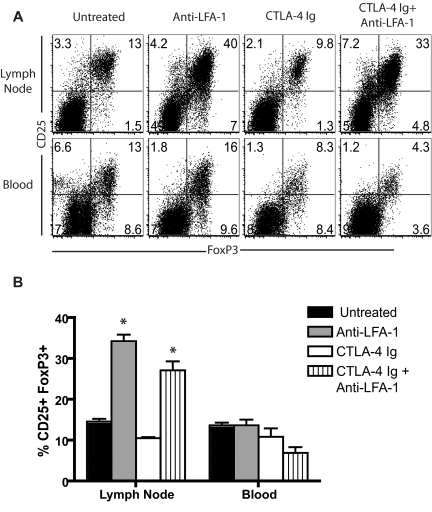

Blockade of the LFA-1 molecule resulted in increased CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg frequency in the LNs

Our data revealed that activated graft-specific T cells were relatively enriched in the peripheral LNs after LFA-1 blockade, whereas non-graft-specific naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were relatively excluded. As to how this might this result in prolongation of graft survival, we hypothesized that retention in the LNs might provide an increased opportunity for regulation by Tregs. To test this, B6 mice that received a BALB/c skin graft and treatment with CTLA-4 Ig alone or anti–LFA-1 alone or in combination with CTLA-4 Ig were killed on day 9 after transplantation, and LN-resident and circulating T cells were assessed for intracellular FoxP3 expression. We observed a profound increase in the frequency of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in the graft-draining LNs of mice that received anti–LFA-1 alone (P = .0043 vs untreated) or in combination with CTLA-4 Ig (P = .0022 vs untreated; Figure 5A-B). This increase was not observed in the peripheral blood (Figure 5A-B) or spleen (supplemental Figure 5), in which similar frequencies of CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs were observed in all treatment groups. However, a statistically significant increase in CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs was also observed in the nondraining LNs of anti–LFA-1–treated mice compared with untreated mice (P < .05, supplemental Figure 5), indicating that the enrichment in FoxP3+ Tregs in peripheral LNs observed in anti–LFA-1–treated animals is not specific for Ag-draining LNs.

Figure 5.

Blockade of the LFA-1 molecule resulted in increased CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs frequency in the LNs. (A) B6 recipients of BALB/c SG were treated with anti–LFA-1 alone, CTLA-4 Ig alone, or a combination of anti–LFA-1 plus CTLA-4 Ig, and graft draining LNs and peripheral blood were isolated 9 days after skin grafting. Cells were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD25, and anti-FoxP3, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are gated on CD4+ T cells are representative of 2-3 experiments (n = 6-9 mice/group). (B) Summary data from 2-3 independent experiments with a total of 6-9 mice per group are shown. Frequencies of CD25+ FoxP3+ cells in the LNs were significantly increased in animals treated with anti–LFA-1 alone (P = .0043) and in those treated with anti–LFA-1 plus CTLA-4 Ig (P = .0022) compared with untreated control animals. Frequencies of CD25+Foxp3+ T cells in the peripheral blood were not affected by treatment with anti–LFA-1.

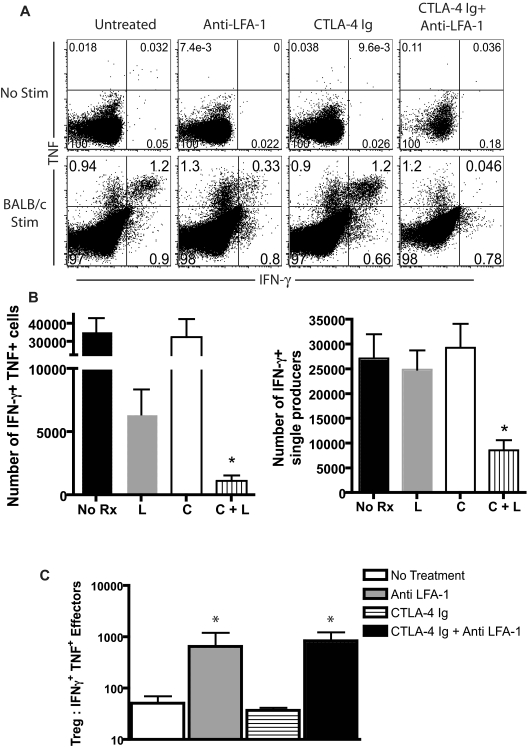

LFA-1 blockade influences cytokine production and increases the ratio of Tregs to Teffs

We next sought to determine the effect of the increased frequency of Tregs on the effector function of the activated, graft-specific CD8+ T cells present in graft-draining LNs. B6 mice were transplanted with BALB/c skin grafts and treated with CTLA-4 Ig alone, anti–LFA-1 alone, or both on days 0 and 2. On day 10 after transplantation, draining LNs were harvested and intracellular cytokine staining was performed. After ex vivo restimulation with BALB/c splenic stimulators, we observed a reduction of the frequency of double-positive TNF+IFN-γ+ producers as a percentage of total remaining CD8+ T cells in animals treated with anti–LFA-1 alone compared with untreated controls or those treated with CTLA-4 Ig alone. However, anti–LFA-1 in combination with CTLA-4 Ig resulted in a further reduction in the frequency of double-cytokine producers (Figure 6A). Factoring in the reduction in total CD8+ T cells after LFA-1 blockade, the total number of double cytokine–secreting effectors was reduced > 3-fold in CTLA-4 Ig/anti–LFA-1–treated animals compared with animals treated with anti–LFA-1 alone, (Figure 6B; P < .05) and more than 10-fold in animals treated with anti–LFA-1 and CTLA-4 Ig compared with untreated animals (Figure 6B, P < .0001). Therefore, LFA-1 and CD28 blockade synergize in diminishing the total number of competent cytokine-producing Teffs after transplantation (Figure 6B). We also calculated the absolute number of Tregs present in the draining LNs, and compared the ratio of Tregs to cytokine-secreting Teffs between the groups. The results revealed a significant increase in the ratio of Tregs to Teffs in the LNs of animals that received anti–LFA-1 alone (P = .0095 compared with untreated mice) or in combination with CTLA-4 Ig (P = .0043 compared with untreated mice; Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

LFA-1 blockade influences cytokine production and increases the ratio of Tregs to Teffs. B6 recipients of BALB/c SG were treated with anti–LFA-1 alone, CTLA-4 Ig alone, or a combination of anti–LFA-1 plus CTLA-4 Ig, and graft-draining LNs were isolated 9 days after skin grafting. Cells were restimulated with irradiated BALB/c responders for 4 hours and stained intracellularly for cytokines as described in “Methods.” (A) Data shown are gated on CD8+ T cells and are representative of 3 independent experiments with 8-9 mice per group. (B) Absolute numbers of double-positive (TNF+IFNγ+), and single IFNγ+ producers in draining LNs are shown. Data shown are combined from 2 independent experiments with a total of 3-6 mice per group. A statistically significant decrease in both IFN-γ+TNF+ double producers and IFN-γ+ single producers was observed only in animals that received both anti–LFA-1 and CTLA-4 Ig, (P < .0001 compared with untreated and P < .05 compared with anti–LFA-1 alone). L indicates anti–LFA-1; C, CTLA-4 Ig. (C) The ratio of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells to IFN-γ-secreting Teffs was statistically significantly increased in LFA-1–treated animals (P = .0095) and in LFA-1 + CTLA-4 Ig–treated animals (P = .0043) compared with untreated controls. Data shown are summarized from 2 experiments with a total of 3-6 mice per group.

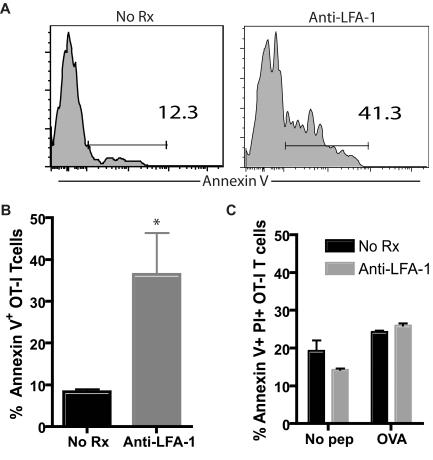

Teffs undergo apoptosis in draining LNs in anti–LFA-1–treated animals

We hypothesized that the retention of Teffs in LNs in the presence of a higher density of Tregs might lead to an increase in apoptosis in these cells. To test this, we adoptively transferred 5 × 106 OVA-specific OT-I T cells into naive B6 mice, which were grafted with OVA-expressing skin grafts and then left untreated or received anti–LFA-1 mAb. Mice were killed 9 days after transplantation, LNs were harvested, and Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells were analyzed for apoptosis induction by annexin V staining. As shown in Figure 7, we observed a significant increase in the frequency of annexin V+CD8+Thy1.1+ T cells in mice treated with anti–LFA-1 compared with untreated controls (P < .05). These results suggested that the activated Teffs retained in draining LNs in the presence of high frequencies of Tregs were induced to undergo apoptosis there. To further address whether the observed increase in FoxP3+ Tregs was required for the observed increase in graft-specific effector T-cell apoptosis in the presence of LFA-1 antagonism, we conducted an in vitro experiment to determine whether anti–LFA-1, in the absence of increased frequencies of FoxP3+ Tregs, could affect Teff apoptosis directly. Briefly, OT-I T cells were stimulated with peptide Ag in the presence or absence of LFA-1 for 72 hours, and CD8+ Thy1.1+ T cells were then assayed for apoptosis by annexin V/propidium iodide staining. In this in vitro setting in which we controlled for the frequencies of FoxP3+ Tregs between groups, we failed to observe an increase in apoptotic OT-I Teffs in the presence of anti–LFA-1 (Figure 7C). Therefore, we concluded that the increase in apoptosis observed in vivo was not a direct effect of LFA-1 antagonism.

Figure 7.

Teffs undergo apoptosis in draining LNs in anti–LFA-1–treated animals. Donor-specific Thy1.1+ OT-I T cells were adoptively transferred into B6 recipients; 48 hours later, mice received an mOVA skin graft and were treated as indicated. Draining LNs were harvested on day 10 after transplantation, and donor-reactive Thy1.1+ T cells were stained with annexin V as described in “Methods.” (A-B) The frequency of annexin V+ graft-specific T cells was higher in anti–LFA-1–treated recipients than in untreated controls (P < .05). Data shown are gated on CD8+ Thy1.1+ T cells and are representative (A) or a summary (B) of 2 independent experiments with a total of 6 mice per group. (C) OT-I T cells were stimulated in vitro with OVA peptide in the presence or absence of anti–LFA-1 mAb (100 μg/mL). Seventy-two hours later, Thy1.1+ CD8+ T cells were analyzed for apoptosis using annexin V/propidium iodide staining for flow cytometry. Results indicated no difference in the amount of apoptosis between the treatment groups either in the presence or absence of Ag. Data shown are an average of 3 wells per culture condition and are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Continuous LFA-1 blockade results in persistent alterations in the LN T-cell profile and indefinite graft survival

Because the animals in our original cohort were treated with CTLA-4 Ig and anti–LFA-1 as induction therapy only, the above results led us to ask whether continuous blockade of the LFA-1 pathway would further prolong graft survival. To test this, we treated B6 recipients of fully allogeneic BALB/c skin grafts with either the standard regimen of CTLA-4 Ig and anti–LFA-1 on days 0, 2, 4, and 6, or the same regimen of CTLA-4 Ig with an extended course of anti–LFA-1 on days 0, 2, 4, and 6 and weekly thereafter. Results indicated that the continuous blockade of LFA-1 resulted in a significant prolongation in graft survival compared with those animals receiving a short course of treatment (supplemental Figure 6A). Indeed, during the 60 days of follow-up, none of the animals treated with maintenance LFA-1 blockade rejected their grafts. To determine whether the T-cell changes observed early after LFA-1 antagonism persisted in these recipients, we compared T-cell profiles in the draining LNs between animals that had been treated with a short course of anti–LFA-1 and anti–CTLA-4 Ig and were rejecting their grafts at the time of killing (day 44) with the T-cell profiles of those that had received a maintenance anti–LFA-1 and had continued graft survival. Results indicated that the frequencies of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, the CD62L expression on these cells, and the frequencies of FoxP3+ Tregs in draining LNs of rejecting animals had returned to baseline frequencies, whereas the animals treated with maintenance anti–LFA-1 exhibited persistent changes in their T-cell profiles, including a reduction in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, reduced CD62L expression, and increased FoxP3+ Treg frequencies in the draining LNs (supplemental Figure 6B-E). These data therefore indicated that the T-cell profile observed in anti–LFA-1–treated animals early after transplantation was no longer present at the time of rejection, and demonstrated that continued LFA-1 antagonism and a persistent increase in the frequencies of FoxP3+ T cells in draining LNs could result in indefinite allograft survival.

Discussion

In the present study, we sought to understand the mechanisms underlying the ability of LFA-1 blockade to synergize with CD28 costimulation blockade in inhibiting graft rejection. Our data suggested that treatment with anti–LFA-1 mAb resulted in a profound reorganization of lymphocyte subsets within peripheral LNs in vivo. Specifically, naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were relatively excluded from peripheral LNs, whereas graft-specific activated Teffs and Tregs were found to be relatively enriched in the peripheral LNs after LFA-1 blockade. The ability of LFA-1 antagonism to result in the exclusion of naive T cells from peripheral LNs and enrichment of FoxP3+ T cells was an Ag-independent effect, because we observed similar results in nondraining LNs of mice that did not receive transplants. The relative enrichment of these cell types and the resulting increase in the Treg:Teff ratio might allow for increased effectiveness of regulation in vivo, resulting in the attenuation of graft-specific T-cell responses. LFA-1 antagonism also synergized with CTLA-4 Ig to decrease the number of highly competent, graft-specific, multi-cytokine-producing Teffs after transplantation. Because long-term graft survival was only observed after combined blockade of both the LFA-1 and CD28 pathways, we conclude that this reduction in multi-cytokine-producing effectors may be critical for the prolongation of graft survival in this model.

What is the basis of this differential impact on naive versus activated T-cell trafficking? It is well known that LFA-1 is required for T-cell extravasation into peripheral LNs.17–19 Naive T cells rapidly circulate through peripheral LNs and the bloodstream, relying on LFA-1/ICAM interactions for this process. Therefore, blockade of LFA-1 likely results in the relative exclusion of naive T cells from LNs because of their inability to reenter the LNs from the bloodstream. In contrast, our observation that graft-specific Teffs are retained in LNs was likely due to the fact that these cells do not rapidly recirculate but instead remain anchored in the peripheral LNs after Ag recognition and activation due to down-regulation of the S1P1 receptor after activation.37 One caveat of these data is that the mOVA system is a surrogate model of minor Ag disparity only, and thus may not be fully comparable to a system in which the donor and recipient have complete MHC disparity. Efforts to identify and track endogenous allospecific T cells during transplantation to confirm these findings in a non-TCR-transgenic system of complete MHC disparity are ongoing.

Our results revealed that Tregs were selectively enriched in the peripheral LNs after LFA-1 blockade. These data were somewhat surprising given the fact that FoxP3+ Tregs express LFA-1 at levels similar to those of naive T cells.38 We interpret these findings to mean either that Tregs do not recirculate through the blood and peripheral LNs as quickly as naive T cells and therefore are not as rapidly affected by the presence of LFA-1–blocking Ab, or that Tregs can rely on some other receptor to gain reentry into peripheral LNs in the presence of anti–LFA-1. The observed increase in the Treg:Teff ratio suggests that the ability of Tregs to suppress Ag-specific T-cell responses may be enhanced. This conclusion is supported by our findings demonstrating that increased Teff apoptosis was not observed when T cells were incubated with anti–LFA-1 in vitro, indicating that the increased frequency of FoxP3+ Tregs may be necessary for the enhanced graft-specific effector T-cell apoptosis observed in vivo. Indeed, numerous studies have shown that the ratio of Tregs to Teffs is a critical determinant of the degree of suppression achieved.39 However, studies also exist to suggest that LFA-1/ICAM interactions are required for CD4+FoxP3+ Treg-suppressor function in vitro.38 Therefore, further studies on the requirement for LFA-1 on Tregs in vivo are warranted.

The results presented in this study suggest that LFA-1 antagonism may function to sequester graft-specific Teffs in the LNs in the presence of a higher frequency of FoxP3+ Tregs. Is this effect sufficient to induce tolerance? Our graft survival data in animals receiving only a short course of LFA-1 blockade would suggest not, and experiments examining the effects of maintenance LFA-1 blockade revealed that longer-term graft survival can be achieved by continuous blockade of this pathway (with CTLA-4 Ig induction). Therefore, these data suggest that LFA-1 antagonism is not tolerance inducing, but merely inhibits accession of T cells to the graft. This notion is supported by a recent report assessing the ability of LFA-1 to inhibit T-cell trafficking into allografts.40 However, work in nonhuman primates revealed that treatment with anti–LFA-1 and rapamycin resulted in long-term graft-survival of islet allografts even after discontinuation of all immunosuppression.34 This discrepancy may be explained by the stringency of the model system used in these studies.

While our study suggested that reorganization of the distribution of naive versus activated Teffs after LFA-1 blockade might be one mechanism underlying the observed prolongation in graft survival, there may be additional effects of blockade of the LFA-1/ICAM interaction, including disruption of the immunologic synapse and decreased costimulatory signals.22 Furthermore, it has been reported that anti–LFA-1–induced long-term graft survival requires the activity of both NK cells41 and NK T cells,42 which were postulated to modulate the responses of host immune cells in a perforin- and an IFN-γ-dependent manner, respectively.41,42 How do our results fit with these observations? It is possible that the requirement for NK T cell–derived IFN-γ may potentiate the suppressive capacity of Tregs through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase–dependent mechanisms.43 These activated Tregs, which are present in the LNs at higher frequencies in anti–LFA-1–treated animals, could then mediate long-term graft survival.

Understanding the mechanisms by which blockade of the LFA-1 pathway may result in attenuation of Ag-specific T-cell responses is highly clinically relevant, because the use of LFA-1 blockade is being investigated for clinical use in transplantation and potentially for GVHD.35,36 Anti–human LFA-1 (efalizumab) was originally developed for use in psoriasis,23,24 but 2 recent pilot studies showed utility in preventing graft rejection in patients receiving islet allografts.32,35,36 Unfortunately, further clinical trials in transplantation have been hampered by the fact that 4 cases of progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy have been reported in psoriasis patients receiving long-term courses of efalizumab.44 However, the risk/benefit profile of efalizumab treatment is significantly different in transplantation and GVHD patients compared with that of the psoriasis population.

In summary, our results identify the reorganization and/or sequestration of different T-cell subsets as one potential mechanism underlying the therapeutic effect of LFA-1 blockade in an experimental transplantation model. This finding is a novel purported mechanism of action for anti–LFA-1 mAbs. However, sequestration of activated effectors in the peripheral LNs as a mechanism underlying the attenuation of Ag-specific T-cell responses has previously been described as the mode of action by which the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 inhibits graft rejection.45,46 Therefore, further research on maximizing the retention of activated graft-specific effectors in the peripheral LNs, or increasing their frequency of apoptosis there, might increase the effectiveness in inhibiting donor-reactive T-cell responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr William H. Kitchens and Dr I. Raul Badell for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI81789 and AI073707 (to M.L.F.) and AI40519 (to C.P.L.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: N.M.R. performed the research and wrote the manuscript; T.L.F. and M.E.W. performed the research; A.D.K. analyzed and interpreted the data; C.P.L. designed the research and analyzed and interpreted the data; and M.L.F. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mandy L. Ford, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery and Emory Transplant Center, Emory University, 101 Woodruff Circle, Suite 5105 WMB, Atlanta, GA 30322; e-mail: mandy.ford@emory.edu.

References

- 1.Jenkins MK, Schwartz RH. Antigen presentation by chemically modified splenocytes induces antigen-specific T cell unresponsiveness in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 1987;165:302–319. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ML, Larsen CP. Translating costimulation blockade to the clinic: lessons learned from three pathways. Immunol Rev. 2009;229(1):294–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson CB, Allison JP. The emerging role of CTLA-4 as an immune attenuator. Immunity. 1997;7(4):445–450. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salomon B, Bluestone JA. Complexities of CD28/B7: CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenschow D, Zeng Y, Thistlethwaite J, et al. Long-term survival of xenogeneic pancreatic islet grafts induced by CTLA4Ig. Science. 1992;257:789–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1323143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azuma H, Chandraker A, Nadeau K, et al. Blockade of T-cell costimulation prevents development of experimental chronic renal allograft rejection [see comments]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(22):12439–12444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson TC, Alexander DZ, Winn KJ, Linsley PS, Lowry RP, Larsen CP. Transplantation tolerance induced by CTLA4-Ig. Transplantation. 1994;57(12):1701–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirk AD, Harlan DM, Armstrong NN, et al. CTLA4Ig and anti-CD40 ligand prevent renal allograft rejection in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8789–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levisetti MG, Padrid PA, Szot GL, et al. Immunosuppressive effects of human CTLA4Ig in a non-human primate model of allogeneic pancreatic islet transplantation. J Immunol. 1997;159(11):5187–5191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, et al. A Phase III Study of Belatacept-based Immunosuppression Regimens versus Cyclosporine in Renal Transplant Recipients (BENEFIT Study). Am J Transplant. 2010;10(3):535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders ME, Makgoba MW, Sharrow SO, et al. Human memory T lymphocytes express increased levels of three cell adhesion molecules (LFA-3, CD2, and LFA-1) and three other molecules (UCHL1, CDw29, and Pgp-1) and have enhanced IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1988;140(5):1401–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okumura M, Fujii Y, Inada K, Nakahara K, Matsuda H. Both CD45RA+ and CD45RA- subpopulations of CD8+ T cells contain cells with high levels of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 expression, a phenotype of primed T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150(2):429–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostermann G, Weber KS, Zernecke A, Schroder A, Weber C. JAM-1 is a ligand of the beta(2) integrin LFA-1 involved in transendothelial migration of leukocytes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(2):151–158. doi: 10.1038/ni755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76(2):301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmann MF, McKall-Faienza K, Schmits R, et al. Distinct roles for LFA-1 and CD28 during activation of naive T cells: adhesion versus costimulation. Immunity. 1997;7(4):549–557. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pribila JT, Quale AC, Mueller KL, Shimizu Y. Integrins and T cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:157–180. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kavanaugh AF, Lightfoot E, Lipsky PE, Oppenheimer-Marks N. Role of CD11/CD18 in adhesion and transendothelial migration of T cells. Analysis utilizing CD18-deficient T cell clones. J Immunol. 1991;146(12):4149–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamann A, Jablonski-Westrich D, Duijvestijn A, et al. Evidence for an accessory role of LFA-1 in lymphocyte-high endothelium interaction during homing. J Immunol. 1988;140(3):693–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warnock RA, Askari S, Butcher EC, von Andrian UH. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1998;187(2):205–216. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham C, Griffith J, Miller J. The dependence for leukocyte function-associated antigen-1/ICAM-1 interactions in T cell activation cannot be overcome by expression of high density TCR ligand. J Immunol. 1999;162(8):4399–4405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ragazzo JL, Ozaki ME, Karlsson L, Peterson PA, Webb SR. Costimulation via lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 in the absence of CD28 ligation promotes anergy of naive CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(1):241–246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011397798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolls MR, Gill RG. LFA-1 (CD11a) as a therapeutic target. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(1):27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szot GL, Zhou P, Sharpe AH, et al. Absence of host B7 expression is sufficient for long-term murine vascularized heart allograft survival. Transplantation. 2000;69(5):904–909. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003150-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandelbrot DA, Furukawa Y, McAdam AJ, et al. Expression of B7 molecules in recipient, not donor, mice determines the survival of cardiac allografts. J Immunol. 1999;163(7):3753–3757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzler B, Gfeller P, Bigaud M, et al. Combinations of anti-LFA-1, everolimus, anti-CD40 ligand, and allogeneic bone marrow induce central transplantation tolerance through hemopoietic chimerism, including protection from chronic heart allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2004;173(11):7025–7036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rayat GR, Gill RG. Indefinite survival of neonatal porcine islet xenografts by simultaneous targeting of LFA-1 and CD154 or CD45RB. Diabetes. 2005;54(2):443–451. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolls MR, Coulombe M, Yang H, Bolwerk A, Gill RG. Anti-LFA-1 therapy induces long-term islet allograft acceptance in the absence of IFN-gamma or IL-4. J Immunol. 2000;164(7):3627–3634. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolls MR, Coulombe M, Beilke J, Gelhaus HC, Gill RG. CD4-dependent generation of dominant transplantation tolerance induced by simultaneous perturbation of CD154 and LFA-1 pathways. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):4831–4839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isobe M, Yagita H, Okumura K, Ihara A. Specific acceptance of cardiac allograft after treatment with antibodies to ICAM-1 and LFA-1. Science. 1992;255:1125–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.1347662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corbascio M, Ekstrand H, Osterholm C, et al. CTLA4Ig combined with anti-LFA-1 prolongs cardiac allograft survival indefinitely. Transpl Immunol. 2002;10(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(02)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corbascio M, Mahanty H, Osterholm C, et al. Anti-lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 monoclonal antibody inhibits CD40 ligand-independent immune responses and prevents chronic vasculopathy in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. Transplantation. 2002;74(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200207150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Gray GS, Vallera DA. Coblockade of the LFA1:ICAM and CD28/CTLA4:B7 pathways is a highly effective means of preventing acute lethal graft-versus-host disease induced by fully major histocompatibility complex-disparate donor grafts. Blood. 1995;85(9):2607–2618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poston RS, Robbins RC, Chan B, et al. Effects of humanized monoclonal antibody to rhesus CD11a in rhesus monkey cardiac allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69(10):2005–2013. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badell IR, Russell MC, Thompson PW, et al. LFA-1-specific therapy prolongs allograft survival in rhesus macaques. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(12):4520–4531. doi: 10.1172/JCI43895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turgeon NA, Avila JG, Cano JA, et al. Experience with a novel efalizumab-based immunosuppressive regimen to facilitate single donor islet cell transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(9):2082–2091. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Posselt AM, Bellin MD, Tavakol M, et al. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetics using an immunosuppressive protocol based on the anti-LFA-1 antibody efalizumab. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(8):1870–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, et al. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427(6972):355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran DQ, Glass DD, Uzel G, et al. Analysis of adhesion molecules, target cells, and role of IL-2 in human FOXP3+ regulatory T cell suppressor function. J Immunol. 2009;182(5):2929–2938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30(5):636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setoguchi K, Schenk AD, Ishii D, et al. LFA-1 LFA-1 antagonism inhibits early infiltration of endogenous memory CD8 T cells into cardiac allografts and donor-reactive T cell priming. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):923–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beilke JN, Kuhl NR, Van Kaer L, Gill RG. NK cells promote islet allograft tolerance via a perforin-dependent mechanism. Nat Med. 2005;11(10):1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/nm1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seino KI, Fukao K, Muramoto K, et al. Requirement for natural killer T (NKT) cells in the induction of allograft tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(5):2577–2581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041608298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mellor AL, Munn DH. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(10):762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carson KR, Focosi D, Major EO, et al. Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab, and efalizumab: a Review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) Project. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(8):816–824. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brinkmann V, Cyster JG, Hla T. FTY720: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 in the control of lymphocyte egress and endothelial barrier function. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(7):1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cyster JG. Chemokines, sphingosine-1-phosphate, and cell migration in secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:127–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.