Abstract

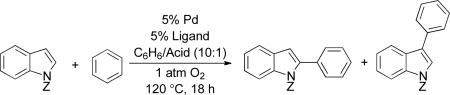

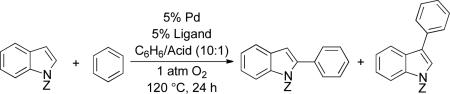

Palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidative cross-couplings of indoles and benzene have been achieved by using 4,5-diazafluorene derivatives as ancillary ligands. Proper choice of the neutral and anionic ligands enables control over the reaction regioselectivity.

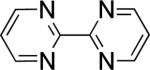

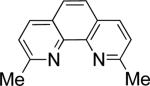

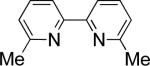

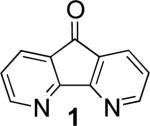

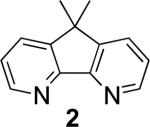

Biaryls are an important structural motif ubiquitous in diverse classes of organic molecules, including pharmaceuticals, organic dyes, agrochemicals and conducting polymers.1 In recent years, considerable attention has focused on the development of methods for arylation of arene C–H bonds.2 The direct oxidative coupling of two arenes (eqn 1) is among the most attractive synthetic routes to biaryls,2h,3 but such methods face numerous intrinsic challenges, including controlling the regioselectivity in the functionalization of substituted (hetero)arenes, achieving selective cross- vs. homocoupling of the substrates, and identification of an atom-economical oxidant for the reaction. Here, we show that use of the diazafluorene derivatives, 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one (1) and 9,9-dimethyl-4,5-diazafluorene (2), as ancillary ligands for a PdII catalyst enables aerobic oxidative cross-coupling of indoles with benzene, with selectivity for C2 and C3 indole-arylation products.

|

(1) |

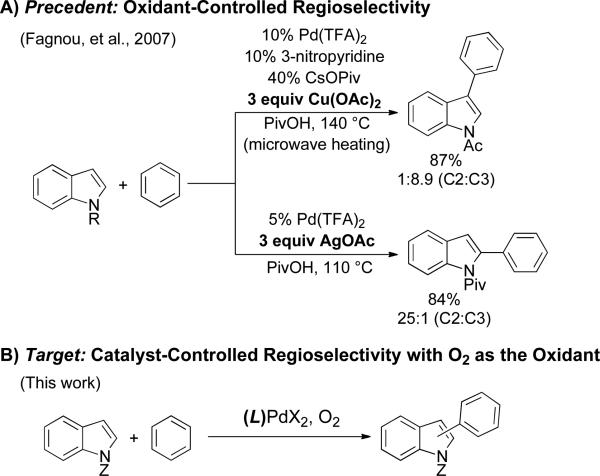

The majority of Pd-catalyzed methods for oxidative cross-coupling of (hetero)arenes employ stoichiometric organic or transition-metal oxidants, such as benzoquinone (BQ), AgI, or CuII.3 Replacement of these oxidants with O2 represents a significant fundamental challenge that has important implications for practical applications of these methods;4,5 however, only limited success has been achieved thus far.6 Several observations suggest that the role of the oxidant in these reactions is not limited to reoxidation of these Pd0.7 For example, oxidants have been shown to promote C–C reductive elimination from Pd(II)8 and to control the regioselectivity of oxidative cross-coupling reactions.3a-d,9 In 2007, Fagnou and co-workers reported Pd-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling of indoles with benzene in which they demonstrated selective functionalization of the indole C3 position when Cu(OAc)2 was used as the oxidant,3a but C2 selectivity with AgOAc as the oxidant (Scheme 1A).3b These observations provide the foundation for the present investigation.

Scheme 1.

Oxidant-Controlled Regioselectivity.

We demonstrated recently that the diazafluorenone ligand 1 promotes acetoxylation of π-allyl-PdII species, enabling benzoquinone to be replaced by O2 as the oxidant in Pd-catalyzed allylic C–H acetoxylation reactions.10 This result prompted us to consider whether analogous ligand-based strategies could be used to achieve oxidative cross-coupling of (hetero)arenes with O2 as the oxidant, preferably with control over the reaction regioselectivity (Scheme 1B).

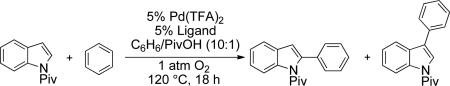

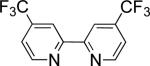

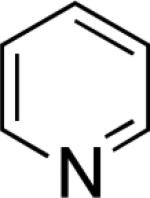

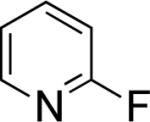

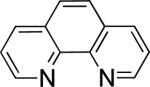

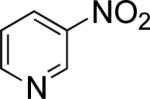

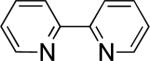

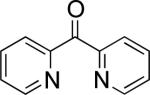

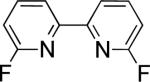

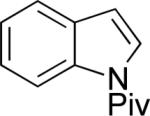

In the present study, we focused our attention on the oxidative coupling of indoles and benzene. A number of different nitrogen ligands, including pyridine, phenanthroline and related derivatives were evaluated in reaction of N-pivalyl indole with benzene. The reactions were carried out with 5 mol % of a PdII source at 120 °C under 1 atm of O2. Benzene served as the substrate and as a cosolvent with pivalic acid (Table 1). Reactions with pyridine and 2-fluoropyridine11 exhibited modest yields (~20-30%), while reactions with bipyridine, phenanthroline and related bidentate ligands (entries 4–11) showed little product formation. Use of diazaflurorene derivatives 1 and 2 gave the best results, with 45% and 66% product yields, respectively.

Table 1.

Identification of a ligand for palladium-catalyzec aerobic oxidative cross-couplinga

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | Yieldb | C2:C3 Selectivityc | Ligand | Yieldb | C2:C3 Selectivityc |

| None | 15% | 1:1 |

|

10% | 1:1 |

|

22% 18%d |

1:1 1.6:1d |

|

0% | - |

|

24% 29%d |

1:1.4 1.9:1d |

|

14% 14% |

1:2.5 1:1.3 |

|

31% 47%d |

2.4:1 2.9:1d |

|

9% | 1:2 |

|

0% 9%e |

- 1:1e |

|

0% | - |

|

0% | - |

|

45% 34%e |

1:1.7 1:1.3e |

|

15% 32%e |

1:2 1:1.7e |

|

66% 41%e |

1:3.8 1:3.1e |

Conditions: 5% Pd(TFA)2 (7.5 μmol), 5% ligand (7.5 μmol), indole (0.15 mmol), PivOH (0.90 mmol), benzene (9.9 mmol), 1 atm O2, 120 °C, 18h.

By 1H NMR (internal standard = tetrachloroethane).

Determined by 1H NMR.

10% ligand.

2.5% ligand

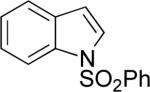

The reaction was further optimized by examining the effect of indole N-substituent and the acid additive on the yield and regioselectivity (Table 2). The highest product yields and regioselectivities were obtained with the N-benzenesulfonyl (SO2Ph) group and propionic acid (Table 2, entry 4). More extensive screening data is provided in the ESI.

Table 2.

Identification of optimized conditions for palladium-catalyzed oxidative coupling of indoles with benzenea

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Z | Acid | Catalyst | Ligand | Yieldb | C2:C3 Selectivityc |

| 1 | Piv | PivOH | Pd(TFA)2 | 2 | 66% | 1:3.8 |

| 2 | Ac | PivOH | Pd(TFA)2 | 2 | 67% | 1:1.2 |

| 3 | SO2Ph | PivOH | Pd(TFA)2 | 2 | 77% | 1:5 |

| 4 | SO2Ph | EtCO2H | Pd(TFA)2 | 2 | 89% | 1:5.8 |

| 5 | SO2Ph | EtCO2H | Pd(OAc)2 | 2 | 63% | 1:2.2 |

| 6 | SO2Ph | EtCO2H | Pd(OPiv)2 | 2 | 68% | 1:1.5 |

| 7 | SO2Ph | EtCO2H | Pd(TFA)2 | 1 | 64% | 1:4.8 |

| 8 | SO2Ph | EtCO2H | Pd(OAc)2 | 1 | 85% | 1.4:1 |

| 9 | SO2Ph | EtCO2H | Pd(OPiv)2 | 1 | 80% | 2:1 |

Conditions: 5% Pd (7.5 μmol), 5% ligand (7.5 μmol), indole (0.15 mmol), acid (0.9 mmol), benzene (9.9 mmol), 1 atm O2, 120 °C, 18h.

By 1H NMR (internal standard = tetrachloroethane).

Determined by 1H NMR analysis.

Several different PdII sources were examined in the course of these studies, and the identity of the anionic ligand was found to have a strong effect on the reaction regioselectivity. These observations resemble results noted recently by Sanford et al. in BQ-promoted oxidative coupling reactions.8d Trifluoroacetate favors the formation of the C3-functionalized product, while pivalate in combination with 2 led to almost no regioselectivity (Table 2, entry 6). When Pd(OPiv)2 was used with the diazafluorenone ligand 1, a switch in regioselectivity was observed, favoring the C2-functionalized product (Table 2, entry 9). The addition of CsOPiv (20 mol%) to the standard reaction mixture led to a similar increase in the formation of C2-arylated products.12 The yield of biphenyl was not rigorously quantified in each case, but it was generally ≤ 20%.

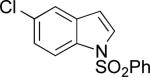

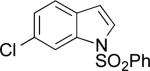

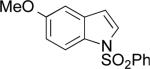

These observations demonstrate that regioselective aerobic oxidative coupling of indoles can be achieved by proper selection of the anionic and neutral ligands for the Pd catalyst. Catalyst system A, with Pd(TFA)2, and ligand 2, favors the C3-functionalized product; and catalyst system B, with Pd(OPiv)2, with 1, favors the C2-functionalized product. These insights were then applied to a small series of other indole substrates (Table 3). The N-pivalyl indole gave superior selectivity under the conditions optimized for the C2 product (entry 1) while the N-benzenesulfonyl indole showed higher regioselectivity under the C3 optimized conditions (entry 2). The 5- and 6-substituted chloro and methoxy derivatives were used to probe the influence of electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups on the reaction outcome. Neither substituent had a significant impact on the yields, but the regioselectivity varied (Table 3, entries 3–6). With the Pd(TFA)2/2 catalyst system (A) the presence of an electron-donating or -withdrawing group in either position led to a deterioration of the regioselectivity. However, with the Pd(OPiv)2/1 catalyst system (B), the regioselectivity was improved by the presence of an electron-withdrawing group in the 5- or 6-positions.

Table 3.

Oxidative cross-coupling of indoles with simple arenesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Indole | Catalyst | Yieldb | C2:C3 Selectivityc |

| 1 |

|

A | 52% | 1:4.4 |

| B | 66% | 4.8:1 | ||

| 2 |

|

A | 66% | 1:5.8 |

| B | 76% | 2:1 | ||

| 3 |

|

A | 71% | 1:1.3 |

| B | 68% | 5:1 | ||

| 4 |

|

A | 71% | 1.4:1 |

| B | 66% | 3.7:1 | ||

| 5 |

|

A | 54% | 1:3.9 |

| B | 71% | 2 3:1 | ||

| 6 |

|

A | 70% | 1:1.3 |

| B | 65% | 2.6:1 | ||

Condition A: 5% Pd(TFA)2 (30 μmol), 5% 2 (30 μmol), indole (0.60 mmol), EtCO2H (3.6 mmol), benzene (39.6 mmol), 1 atm O2, 120 °C, 24h. Condition B: 5% Pd(OPiv)2 (30 μmol), 5% 1 (30 μmol), indole (0.60 mmol, EtCO2H (3.6 mmol), benzene (39.6 mmol), 1 atm O2, 120 °C, 24h.

Isolated as a mixture of C2 and C3 regioisomers

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixture.

Overall, these observations establish that diazafluorene-derived ancillary ligands enable the replacement of stoichiometric transition metals with O2 as the oxidant in Pd-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling of (hetero)arenes. Moreover, optimization of the neutral and anionic ligands permits control over the regioselectivity of the reactions.

The mechanistic basis for these results is not yet understood, but at least two general mechanisms can be considered.13 One involves sequential activation of the indole and benzene at a single PdII center, followed by reductive elimination of the product and reoxidation of Pd0 by O2. An alternative pathway involves activation of indole and benzene at independent PdII centers, followed by transmetalation to afford the PdII(phenyl)(indolyl) intermediate that undergoes reductive elimination of the product. Distinguishing between these possibilities and exploring the basis for the reaction regioselectivity will be an important focus of future work.

A few preliminary mechanistic observations can be noted. When reactions with catalysts A and B were carried out with a 1:1 mixture of C6H6 and C6D6, deuterium kinetic isotope and effects varied from 2.8–3.8, depending upon the specific reaction12. This primary KIE is consistent with a concerted metalation-deprotonation pathway for C–H activation that has been characterized previously in related reactions14. When the reaction was carried out with CD3CO2D as the acid additive, extensive deuterium incorporation was observed into the benzene and the indole substrates. Deuteration of the indole ring occurred primarily at the C3-position, irrespective of the catalyst system, even though catalyst B leads to predominant C2-functionalization. Negligible deuteration occurs in the absence of PdII under these conditions.12 These results, which indicate that C–H activation is reversible for both substrates under the reaction conditions, potentially provide circumstantial support for a transmetalation mechanism, but more work is required before a conclusion can be reached. The relative simplicity of the catalyst systems should facilitate such mechanistic investigations.

We thank Paul White (UW-Madison) for experimental assistance, and we are grateful to the NIH (R01-GM67163/SSS; F32-GM087890/ANC) and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Postdoctoral Program in Environmental Chemistry for financial support of this work. High-pressure instrumentation was supported by the NSF (CHE-0946901).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Reaction optimization details, characterization data and NMR spectra of characterized compounds. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

General procedure for catalytic reactions: A pressure tube fitted with a plunger valve was charged with Pd (0.030 mmol), ligand (0.030 mmol), indole (0.60 mmol), EtCO2H (270 μL, 3.6 mmol) and arene (39.6 mmol). The tube was evacuated and backfilled with O2 (3×), sealed and heated to 120 °C for 24h with vigorous stirring. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature, diluted with EtOAc and washed with sat'd. NaHCO3. The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer washed with EtOAc (2×). The combined organics were dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated by rotatory evaporation. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Et2O in hexanes) to yield the cross-coupled product as a mixture of two isomers.

Notes and references

- 1.Cepanec I. Synthesis of Biaryls. Elsevier; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For relevant reviews, see: Kakiuchi F, Kochi T. Synthesis. 2008;2008:3013.Li B-J, Yang S-D, Shi Z-J. Synlett. 2008:949.Chen X, Engle KM, Wang DH, Yu JQ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5094. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e.Lei AW, Liu W, Liu C, Chen M. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10352. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00486c.You SL, Xia JB. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010;292:165.Liu C, Zhang H, Shi W, Lei A. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1780. doi: 10.1021/cr100379j.Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d.

- 3.For examples of Pd-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling, see ref 2h and references therein, and: Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Science. 2007;316:1172. doi: 10.1126/science.1141956.Stuart DR, Villemure E, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12072. doi: 10.1021/ja0745862.Potavathri S, Dumas AS, Dwight TA, Naumiec GR, Hammann JM, DeBoef B. Tet. Lett. 2008;49:4050. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.04.073.Potavathri S, Pereira KC, Gorelsky SI, Pike A, LeBris AP, DeBoef B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14676. doi: 10.1021/ja107159b.Gong X, Song GY, Zhang H, Li XW. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1766. doi: 10.1021/ol200306y.Wang Z, Li K, Zhao D, Lan J, You J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011 DOI: 10.1002/anie.201101416.

- 4.For reviews of Pd-catalyzed oxidation reactions that employ O2 as the sole oxidant, see: Stahl SS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3400. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630. and references therein.Gligorich K,M, Sigman MS. Chem. Commun. 2009:3854. doi: 10.1039/b902868d.

- 5.Prospects for safe and scalable Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation methods were considered in the recent development of a continuous-flow process: Ye X, Johnson MD, Diao T, Yates MH, Stahl SS. Green Chem. 2010;12:1180. doi: 10.1039/c0gc00106f.

- 6.Pd-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling that use O2 as the terminal oxidant: Dwight TA, Rue NR, Charyk D, Josselyn R, DeBoef B. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3137. doi: 10.1021/ol071308z.Li BH, Tian SL, Fang Z, Shi ZH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1115. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704092.Brasche G, Garcia-Fortanet J, Buchwald SL. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2207. doi: 10.1021/ol800619c.

- 7.For studies of Pd(0) oxidation by O2, see: Muzart J. Chem. Asian J. 2006;1:508. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600202.Stahl SS, Thorman JL, Nelson RC, Kozee MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7188. doi: 10.1021/ja015683c.Konnick MM, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10212. doi: 10.1021/ja046884u.Konnick MM, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5753. doi: 10.1021/ja7112504.Popp BV, Stahl SS. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:2915. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802311.

- 8.Oxidatively-induced reductive elimination from PdII has extensive precedent. For recent examples relevant to catalytic oxidative coupling reactions, see the following and references cited therein: Chen X, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12634. doi: 10.1021/ja0646747.Lanci MP, Remy MS, Kaminsky W, Mayer JM, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15618. doi: 10.1021/ja905816q.Khusnutdinova JR, Rath NP, Mirica LM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7303–7305. doi: 10.1021/ja103001g.Lyons TW, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4455. doi: 10.1021/ja1097918.

- 9.Grimster NP, Gauntlett C, Godfrey CRA, Gaunt MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3125. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell AN, White PB, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15116. doi: 10.1021/ja105829t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izawa Y, Stahl SS. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:3223. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.See supplementary information for additional details.

- 13.The mechanism of these reactions has received relatively little attention. For a recent computational study, see: Meir R, Kozuch S, Uhe A, Shaik S. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:7623–7631. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002724.

- 14.a Gorelsky SI, Lapointe D, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10848–10849. doi: 10.1021/ja802533u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ackermann L. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1315. doi: 10.1021/cr100412j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.