The discussion surrounding the release of celebrity health information to the media is not a new issue for health care professionals to consider. The rapid dissemination of updates concerning the health of a “public person” is now available to a wide audience through Internet communication and social media systems. The “appetite” of the news organizations and the public at large to obtain “breaking news” on a medical topic of interest involving a recognized political figure, sports star, or entertainer needs to be carefully weighed against the current laws intended to protect the privacy of the individual. Minute-by-minute, no longer day-to-day, updates seem essential through a variety of media, including a mobile phone and other handheld electronic devices. Competition between news services has only increased the demand for the latest news. Regrettably, the more sensational and potentially unbelievable the health-related news story, the more likely it will be distributed faster and farther to a larger audience using contemporary electronic media. Two fairly recent events provide reason to pause and consider both the legal and the ethical standards involved in release of medical information by health care professionals.

The tragic shooting of Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords on January 8, 2011, captured the attention and concern of individuals throughout the world. She was one of 19 victims of this mass shooting, and there were 6 fatalities. Treating physicians were quick to reveal information regarding her condition to a shocked public. Regular updates on the nature of her injuries and the progress of her recovery were provided to an absorbed press trying to offer answers to a gripped national and international audience. According to separate reports, Ms Giffords’ husband, Astronaut Mark Kelly, gave the University Medical Center in Tucson, AZ, permission to disclose certain facts relevant to her progress and prognosis.1 A spokesperson for the hospital stated that any of the information released to the press would be discussed before-hand with her family.1

Despite Mr Kelly’s approval, some privacy experts remained surprised at the amount and type of health care data the press were privy to. Included were concerns of whether Ms Giffords herself would have approved of having so many medical and personal details being shared with a wide audience.1

Compared to Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords’ extensive media exposure, the release of health information to the press surrounding the serious medical condition of Steve Jobs (CEO of Apple Inc) was far more reserved. Mr Jobs gave permission to release further information to the public several days after a Wall Street Journal article reported that he had received a liver transplant 2 months previously.2 During a June 2009 press release, the head of transplantation James D. Eason, MD, of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, acknowledged that Mr Jobs had earlier undergone a liver transplant at that institution.3 The release detailed his progression through the United Network for Organ Sharing system as well as limited information about his present condition and prognosis.3 The report finished with a statement confirming that the “hospital respect[s] and protect[s] every patient’s private health information and cannot reveal any further information on the specifics of Mr Jobs’ case.”3 On August 24, 2011, Mr Jobs resigned his leadership position, indicating he “could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple’s CEO.”4 No further information was provided regarding this decision.4

The current article will explore the tort law and constitutional restrictions placed on the disclosure of information into the public forum. This will lay the framework for a discussion related to the exchange of health care information. Both ethical and legal standards are described with emphasis on the important role of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

The History of Communicative Laws

Tort Law and Constitutional Law Concepts. An appreciation for the tenets of tort law may help foster a better understanding of the flow of information into the public sector. Torts are defined as wrongs that result in injury or harm.5 The primary goal of tort law is to award compensation for damages and to deter others from committing similar acts.5

Two legal theories, defamation and invasion of privacy, help to balance an individual’s right to maintain his or her reputation and privacy against the public’s right to be made aware of and “police” the actions involving public officials and figures.5

Defamation. Defamation comprises 2 complementary communicative torts: libel and slander.5 Libel is traditionally described as the more serious and entails the written word, whereas slander typically involves a verbal offense. Both claims of slander and libel require that the information projected be false.

Private parties must prove only that any false information was “negligently” entered into the public forum. This distinction in proof required stems from the greater ease that public officials and figures have to reverse their tarnished image through ready access to a captive media audience.5,6

Courts have largely been opposed to holding political satire and parody as a violation under libel and slander torts.5,7 Both satire and parody are often viewed as opinion rather than fact. Furthermore, those viewing or listening are either initially aware or informed through disclaimers within the publication that the message content is not true and meant only to foster a comedic forum of exchange.5,7,8

Invasion of Privacy. It is argued that the largest volume of legal precedent involving the right to privacy has evolved from common law (judge made) tort actions.9 Right to privacy laws likely did not come of age until 1960, when the renowned legal scholar William Prosser characterized invasion of privacy into 4 separate torts.9

Unlike defamation law, which protects against false accusations alone, invasion of privacy laws help to shield true statements from entering into the public forum.

The 4 categories of tort law privacy actions arising from Prosser’s work5 include the following:

Appropriation—the unauthorized use of a person’s name or picture for commercial advantage;

Intrusion—intrusion on a person’s affairs or seclusion in a nonpublic setting involving acts objectionable to a reasonable person;

False light—publication of facts attributing views that the person did not hold or actions he or she did not take;

Public disclosure of private facts—disclosure of embarrassing private facts about a person.

Public disclosure of private facts may include divulging information that, although true, is still objectionable to the reasonable person. Courts have also considered that activities consistent with a newsworthy event may be protected.5 However, other courts have held that information so offensive as to constitute sensational prying into one’s private matters only for the purpose of sensationalism can be restricted regardless of its newsworthy content.5,10

Patient-Related Privacy and Confidentiality

Both legal and ethical standards influence the obligation of health care professionals to maintain the privacy and confidentiality of patient information.5,11

Moral and Ethical Obligations. Patients should feel comfortable in openly relaying information to their health care professionals. When patients fear that the information they provide will not remain within the confidences of the immediate health care environment, they may resist offering full disclosure.11,12 The passages of the Hippocratic Oath explicitly address the need for privacy of health information by advocating that “[w]hatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.”12,13 The American Medical Association Principle of Medical Ethics directs physicians to prescribe to the obligation that “[w]hatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.”12,14 The American Nurses’ Association Code of Ethics for Nurses instructs their members that “information pertinent to a patient’s treatment and welfare is disclosed... only to those directly concerned with the patient’s care.12,15

Patient health information should not be disseminated unless an interest of higher priority exists.11 Examples of situations that may necessitate release of patient information include the need to ensure protection of the patient and others as well as certain legal obligations to report.11 The 1976 case of Tarasoff v the Regents of the University of California is perhaps the most famous court decision imposing a duty to warn. After a psychologist and psychiatrist team failed to advise of the potential risk posed by one of their patients, who later committed a murder, the Tarasoff court held that physicians have a duty to warn a third party of the potential threat imposed by one of their patients.11 Other statute-based laws require that certain types of patient health information be reported, including infectious diseases and injuries arising from suspected child abuse and gunshot wounds.11

Common Law Tort Actions. Courts have utilized Prosser’s invasion of privacy elements previously discussed to help guide their decisions involving exchange of patient information.11 In addition, physicians have been found liable for breaching their fiduciary duty to patients and failing to meet the expected standard of care under medical negligence tenets after dissemination.11

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Perhaps no prior piece of legislation has had a greater impact on protecting the flow of patient health care information than HIPAA. As part of its enactment on August 21, 1996, HIPAA regulations required the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to issue standards for the electronic exchange, privacy, and security of health information.16 The final form of these regulations, known as the Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information, took effect in April 2003.12,16

For the first time, the Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information (Privacy Rule) created national standards for the protection of certain types of health information. The Privacy Rule set out tenets for organizations, known as “covered entities,” to regulate the use and disclosure of an individual’s protected health information (PHI). In addition, standards were published on the individual rights to control how each person’s health information could be used.16

Health and Human Services understood that, although it was important to properly ensure protection of an individual’s PHI, the ability of health care professionals to adequately provide quality care to patients required effective flow of patient health information. As a result, the Privacy Rule helps to establish a “balance that permits important uses of information, while protecting the privacy of people.”16

Protected Health Information. The Privacy Rule defines PHI as “all ‘individually identifiable health information’ held or transmitted by a covered entity (health care providers, plans and clearinghouses) or its business associate, in any form or media, whether electronic, paper, or oral.”16 This information includes

demographic data, that relates to: the individual’s past, present or future physical or mental health or condition, the provision of health care to the individual, or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual, and that identifies the individual or for which there is a reasonable basis to believe can be used to identify the individual.16

A central role of the Privacy Rule is to help ensure that only the “minimum necessary” use and disclosure of PHI occur.16 A covered entity must make reasonable efforts to use, disclose, and request only the minimum amount of PHI needed to accomplish the intended purpose of the use, disclosure, or request.17,18

Each covered entity must provide the individual with a notice of its privacy practices.19,20 The notice of privacy must describe the ways in which the covered entity may use and disclose PHI, as well as its duty to protect individual privacy and comply by the terms of the notice. The notice must provide information on the individual’s rights, including the right to voice a complaint with the covered entity and HHS for any believed privacy violations.19,20 The covered entity must make a good faith effort to obtain written consent from patients confirming their receipt of the privacy practices notice.21

A covered entity must obtain the individual’s written authorization for any use or disclosure of PHI that is not for treatment, payment, or health care operations or otherwise permitted or required by the Privacy Rule.22

A covered entity may use and disclose PHI without an individual’s authorization in the following situations16,23:

To the individual patient;

For the purpose of treatment, payment, and health care operations;

After an individual’s opportunity to agree or object;

Incident to an otherwise permitted use and disclosure;

For the purpose of public health interests (eg, disease control) and benefit activities (eg, law enforcement requests); and

For the purposes of research, public health, or health care operations.

Covered entities may rely on professional ethics and best judgments in deciding which of these permissive uses and disclosures to make.16

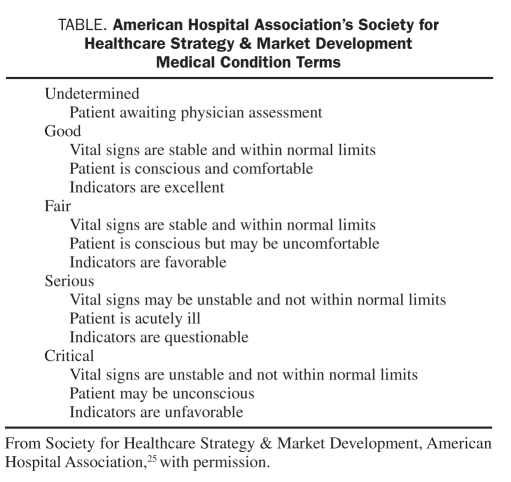

Patient Information Directory. Health care facilities, including hospitals, often maintain a directory of patient contact information.16 When an individual has been informed in advance (through notice of its privacy practices as previously discussed) and has had an opportunity to agree or disagree with its release, the covered entity may disclose the individual’s location within the facility as well as the individual’s general condition to anyone asking for the individual by name.16,24 The condition of the individual disclosed must be limited to a general description of the patient’s condition that does not “communicate specific medical information about the individual.”24 Most commonly, covered entities will restrict the information concerning the individual’s condition to the terms recommended by the American Hospital Association’s Society for Healthcare Strategy & Market Development25 (Table).

TABLE.

American Hospital Association’s Society for Healthcare Strategy & Market Development Medical Condition Terms

When an individual is incapacitated, such as in an emergency situation, the covered entity may disclose the aforementioned prescribed information if it is both consistent with any known prior preferences expressed by the individual and following professional judgment, divulging such information appears to be in the best interests of the individual.16,24 When practically feasible (ie, when the patient is no longer incapacitated), the covered entity must provide the patient the opportunity to object to any future use or disclosure of his or her information.16,24

HIPAA Violation Penalties. Working as a component under HHS, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is responsible for implementation and enforcement of the Privacy Rule standards.16 Although there is no individual right to bring a lawsuit for violation of the Privacy Rule directives, patients may file their complaints with the OCR.12 Covered entities found in violation of HIPAA standards may be at risk of civil monetary penalties.16 Although the law does not specifically charge fines for noncompliance, the Secretary of HHS (through OCR) may impose a civil monetary penalty of up to $100 per person per violation with a maximum of $25,000 per person per violation of a single standard per calendar year.26,27 If the OCR believes that the exchange of individual health information may have risen to the level of criminal activity, the matter may be referred to the US Department of Justice.16 Potential criminal sanctions for “knowingly” obtaining or disclosing PHI in violation of HIPAA regulations include a fine of $50,000 and up to 1 year in prison.28 Health information gained or divulged under false pretenses increases the penalty to $100,000 and up to 5 years of imprisonment. These penalities rise to $250,000 and up to 10 years of imprisonment if the wrongful conduct involves the intent to sell, transfer, or use individually identifiable health information for commercial advantage, personal gain, or malicious harm.16

Conclusion

Most health care professionals are unlikely to care for a celebrity patient and face the controversial issues related to the media. However, the issues of patients’ privacy and the inappropriate disclosure of medical information remain a pivotal concern in the management of all patients. Our responsibilities include not only providing the individual excellent medical care but also conforming to the highest standards of professional responsibilities and ethics. Use of the electronic medical record has resulted in physicians, nurses, technicians, and secretaries having access to a patient’s complete medical history, even when they are not involved in the care of the patient. Unfortunately, the advance in electronic technology has progressed faster than methods to effectively communicate to all health care workers that it is illegal and unethical to review the medical record of a patient, friend, relative, colleague, coworker, or celebrity if that person is not caring for the patient or without proper authorization. Individuals, including physicians, have been terminated from medical centers because of unauthorized access of a medical record, even if the excuse is “just taking a peek” or the patient is not a famous person. Evidence for the repercussions of such unseemly behavior is that 3 employees at the University Medical Center in Tucson, AZ, were apparently fired for their unauthorized access to medical records of victims of the tragedy on January 8, 2011.29 This is probably not a “new” problem, but a long-standing issue that is now significantly exacerbated by electronic forms of communication.

The profound effect of a sudden and potentially catastrophic illness in a friend or loved one is the knowledge and reassurance that the individual will have an excellent medical outcome. This in part explains the fascination of the news media and the public in acquiring the facts and medical details involving a celebrity. Often, these individuals’ personal and professional lives are so transparent that the public responds to their illnesses like a malady affecting an acquaintance, although most have never met the person. However, the privacy of the patient remains sacrosanct and must never be challenged. Unambiguous laws and guidelines are in place to modulate the behavior of health care professionals. The medical care and history of each and every patient must be constantly protected.

Editor’s Note: Mr Steve Jobs died on October 5, 2011, after the manuscript had been accepted for publication. In a statement released by Apple, his family said, Mr Jobs died peacefully today surrounded by his family.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pender K. Giffords’ detalied updates, Jobs’ nondisclosure. San Francisco Chronicle. Thursday, January 20, 2011. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2011/01/19/BUH41HATCA.DTL&ao=all Accessed October 11, 2011

- 2. Slivka E. Methodist University Hospital confirms Steve Jobs liver transplant. MacRumors Web site http://www.macrumors.com/2009/06/23/methodist-university-hospital-confirms-steve-jobs-liver-transplant/ Accessed October 11, 2011

- 3. Steve Jobs receives liver transplant. Methodist Healthcare Web site http://www.methodisthealth.org/methodist/About+Us/Newsroom/News+Archive/Steve+Jobs+Receives+Liver+Transplant Accessed October 11, 2011

- 4.Steve Jobs resigns: the minister of magic steps down: can Silicon Valley’s most disruptive firm prosper without its maker? http://www.economist.com/node/21526948. [Accessed October 11, 2011]. http://www.economist.com/node/21526948 The Economist Web site.

- 5. Galligan TC, Haddon PA, Maraist FL, et al. TORT Law: Cases, Perspectives, and Problems. Revised 4th ed. Newark, NJ: LexisNexis; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dun & Bradstreet, Inc v Greenmoss Builders, 472 US 749 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen W, Varat JD, Amar V. Constitutional Law, Cases and Materials. 12th ed. New York, NY: Foundation Press; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hustler Magazine, Inc v Falwell, 485 US 46 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hudson DL., Jr Privacy and newsgathering. First Amendment Center Web site www.firstamendmentcenter.com/press/topic.aspx?topic=privacy_newsgathering Accessed October 11, 2011

- 10. Toffolini v LFP Publishing Group. United States Court of Appeals. Eleventh Circuit. Web site http://www.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions/ops/200816148.pdf Accessed October 11, 2011

- 11. Moskop JC, Marco CA, Larkin GL, Geiderman JM, Derse AR. From Hippocrates to HIPAA: privacy and confidentiality in emergency medicine; part I: conceptual, moral, and legal foundations. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(1):53–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Annas GJ. The Rights of Patients. 3rd ed. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, History of Medicine Division Greek Medicine: The Hippocratic Oath. NIH Web site http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html Accessed October 11, 2011

- 14. American Medical Association AMA Code of Medical Ethics: principles of medical ethics. AMA Web site www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/principles-medical-ethics.page Accessed October 11, 2011

- 15. American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses. Web site http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategoriesThePracticeofProfessionalNursingEthicsStandards/CodeofEthics.aspx Accessed October 11, 2011

- 16. US Department of Health & Human Services (DHS) Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. DHS Web site http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/summary/privacysummary.pdf Accessed October 11, 2011

- 17. Uses and disclosures of protected health information: general rules. 45 CFR §164.502(b) [Google Scholar]

- 18. Other requirements relating to uses and disclosures of protected health information. 45 CFR §164.514(d) [Google Scholar]

- 19. Notice of privacy practices for protected health information. 45 CFR §164.520(a) [Google Scholar]

- 20. Notice of privacy practices for protected health information. 45 CFR §164.520(b) [Google Scholar]

- 21. Notice of privacy practices for protected health information. 45 CFR §164.520(c) [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uses and disclosures for which an authorization is required. 45 CFR §164.508 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Notice of privacy practices for protected health information. 45 CFR §164.520(a)(1) [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uses and disclosures requiring an opportunity for the individual to agree or to object. 45 CFR §164.510(a) [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nebraska Hospital Association HIPAA Communication Guide for News Media. Web site www.nhanet.org/pdf/hipaa/hipaamediaguide.pdf Accessed October 11, 2011

- 26. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) HIPAA Electronic transactions & code sets: HIPAA Information Series: enforcement of HIPAA standards. http://www.cms.gov/EducationMaterials/Downloads/Enforcement.pdf Accessed October 11, 2011

- 27. General penalty for failure to comply with requirements and standards. 42 USC §1320d-5 [Google Scholar]

- 28. General penalty for failure to comply with requirements and standards, 42 USC §1320d-6 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hensley S. Snooping Tucson hospital workers fired in records breach. NPR Web site http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2011/01/14/132928883/snooping-tucson-hospital-workers-fired-in-records-breach Accessed October 11, 2011