Abstract

Treatment of seniors with Parkinson disease is within the domain of primary care physicians and internists. A good working knowledge of carbidopa/levodopa principles should allow excellent care of most patients, at least during the early years of the disease. Even later, when levodopa responses become more complicated (eg, dyskinesias, motor fluctuations, insomnia, anxiety), levodopa adjustments may be all that is necessary. A dozen tips for optimizing treatment of Parkinson disease are discussed herein.

Parkinson disease (PD) is common, with US prevalence estimates of approximately 1 million patients. Many primary care and internal medicine clinicians defer treatment to neurologists. This may be appropriate if the problems become complex with advancing disease. However, even then, having a knowledgeable primary clinician as an active member of the care team can have a major impact on the patient’s quality of life.

TREATMENT NOT NECESSARILY COMPLICATED

Physicians can easily be overwhelmed with the enormous PD literature, which may generate contradictory therapeutic recommendations. At the time of this writing, searching PubMed with the term Parkinson’s disease treatment generated 32,289 articles; confining the search to the most recent year generated 1825 articles. Moreover, there are multiple PD drugs, and commercial interests advocate for some of these, skewing the discussion.

In truth, treating seniors with PD can be greatly simplified. Seniors, defined in this article as those older than 60 years, do not require complex polypharmacy during the early years of PD. Even later, a simple approach, reinforced by understanding of just a few drugs, may be best for the patient. Herein, a dozen basic principles, or “tips,” for treatment of seniors with PD are provided, which should facilitate primary care clinicians becoming effective PD providers.

TIPS FOR TREATMENT OF SENIORS WITH PD

1. No Drugs Are Proven to Slow PD Progression

Many agents have been proposed to slow PD progression, but no compelling evidence has surfaced in clinical trials. The American Academy of Neurology reviewed the evidenced-based literature in 2006 and concluded that, “No treatment has been shown to be neuroprotective.”1 Since that publication, the only published clinical trial that challenges this statement assessed rasagiline in early PD; a statistically significant effect was documented with the lower of 2 rasagiline doses.2 However, this was a very controversial study with multiple potential confounding factors, leading others to conclude that evidence was insufficient for a rasagiline “neuroprotective” effect.3 Thus, treatment of PD remains symptomatic.

2. Dopamine Replenishment Remains the Key to Symptomatic Treatment

Parkinson disease has long been synonymous with cerebral dopamine depletion, and dopamine replenishment remains the fundamental substrate for medical treatment. Both motor and nonmotor symptoms reflect loss of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system, and these symptoms often respond dramatically to dopamine restoration. However, it is now well-recognized that PD involves much more than loss of dopamine. Other neurotransmitter systems are not only affected late in PD (eg, dementia, levodopa-refractory motor symptoms, dysautonomia) but also early, preceding PD motor symptoms. Early symptoms such as rapid eye movement sleep behavior, olfactory loss, anxiety, or dysautonomia (constipation) may develop 20 or more years before recognizable PD.4 The temporal course of PD, spanning decades, has been formalized in the Braak staging scheme.5

Although PD is now understood to be much more than a dopamine deficiency state, most of the therapeutic gains are achieved through restoring brain dopamine neurotransmission. Understanding how best to accomplish this is key to managing PD.

3. Carbidopa/Levodopa: Most Efficacious and a Good First Choice

The advent of carbidopa/levodopa nearly 4 decades ago was associated with substantially increased longevity, documented in multiple studies of PD cohorts,6 and presumably due to mobilizing akinetic patients. This drug remains the most efficacious treatment. Although new PD drugs are sometimes advocated for initial treatment, they are much more expensive and, for seniors with PD, have few advantages over carbidopa/levodopa.

The oral dopamine agonists pramipexole and ropinirole are the primary alternatives to carbidopa/levodopa as initial treatment. They are efficacious but substantially less so than levodopa.7,8 Moreover, they have troublesome adverse effects, including sedation/sleep attacks9 and pathological behaviors,10 plus an approximately 3-fold risk of hallucinations, compared to carbidopa/levodopa.7,8 Uncommonly, PD patients sometimes experience massive lower limb edema provoked by agonists.7,8 The primary argument for starting therapy with these agonists is to reduce dyskinesia and motor fluctuation risks in early PD (see subsequent discussion). However, during the early years of PD in seniors, dyskinesias and motor fluctuations are not very frequent and usually are unimportant problems.11-13 Of course, the opposite is true in very young people with PD; disease onset before age 40 years is nearly always associated with at least some dyskinesias by 5 years of levodopa treatment.14 However, PD onset before age 40 years is extremely uncommon.

4. You Cannot Save the Best Response for Later

Carbidopa/levodopa is often dramatically beneficial during the initial years of PD, with a very stable (long-duration) response.15 Throughout subsequent years, the response becomes less stable and complete, plus it is often marked by dyskinesias. Without proof, some argue for “saving” the beneficial responses of carbidopa/levodopa for later. However, there is no compelling evidence that deferring treatment allows the benefit to be “cashed in” later. Rather, this likely represents a lost opportunity. It appears that later-developing levodopa response instability is primarily related to PD progression, rather than the duration of levodopa treatment.11,16

Actually, deferring treatment may have longer-term detrimental consequences. If PD patients experience sufficient symptoms to reduce activities, it may be difficult to reverse the established disability. Moreover, emerging literature suggests that staying physically active may actually have a favorable influence on brain integrity and neuroplasticity, possibly neuroprotective in PD.17

5. Generic Immediate-Release 25/100 Carbidopa/Levodopa Is an Excellent Choice

Carbidopa/levodopa dosage is given as 2 numbers, with the first representing the carbidopa component. Carbidopa protects against nausea, and hence formulations with more carbidopa are usually preferable and only slightly more expensive (ie, 25/100 vs 10/100). If nausea is absent, then the amount of carbidopa per dose or per day can be ignored.

The controlled-release formulation has less bioavailability than the immediate-release drug18; it generates more erratic responses and is much slower to “kick in.”19 It is also more expensive than the immediate-release formulation and has complex interactions with food.18 Thus, for routine daytime use, immediate-release carbidopa/levodopa is a better option. The role for controlled-release carbidopa/levodopa is very limited in my practice and will not be addressed further in this article.

Recently, the addition of the catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor entacapone has been advocated for initial therapy as a combination drug with carbidopa/levodopa (Stalevo, Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland). However, a recent randomized clinical trial failed to demonstrate advantages that would offset the considerable additional expense, compared to carbidopa/levodopa alone. 20 The bottom line is this: start therapy with 25/100 immediate-release carbidopa/levodopa.

6. Carbidopa/Levodopa Must be Taken on an Empty Stomach

Levodopa is a large neutral amino acid that crosses the blood-brain barrier via a molecular transporter, which selectively binds all amino acids from that class. Obviously, digestion of dietary proteins liberates amino acids into the circulation, and these compete with levodopa for transport across the blood-brain barrier. This transport system is easily saturated, and administration of carbidopa/levodopa with meals substantially reduces efficacy. To ensure that levodopa passage across the blood-brain barrier is not compromised, patients should be advised to take their carbidopa/levodopa doses an hour or more before, and 2 or more hours after eating.

Pharmacists may dispense carbidopa/levodopa with labeling stating, “Take with meals,” which obviously is incorrect. However, for patients who experience nausea, it is acceptable to take carbidopa/levodopa with dry bread, soda crackers, a banana portion, or some other nonprotein product.

7. There Is no Reason to Restrict Levodopa Dosage: Use What Works Best

Although some advocate keeping the levodopa doses as low as possible, no evidence shows that this strategy has any long-term benefit; clearly, it may result in short-term disability. Once PD patients become sedentary, it may be difficult to reverse this. As mentioned previously, increasing evidence shows that ongoing physical activity and exercise may have a favorable influence on PD progression.17

Managing PD is much like managing type 1 diabetes mellitus with insulin: choose the optimum dose. Management of diabetes mellitus benefits from the measurement of blood glucose, which provides objective confirmation of the optimum insulin dose. Obviously PD has no numeric outcomes to monitor, but rather parkinsonian symptoms and signs, making confirmation of the optimum dose of medication a little more difficult. However, this can be operationally simplified, as follows.

When initiating carbidopa/levodopa in PD, it is conventionally administered 3 times daily and specifically 1 or more hours before meals. Using the 25/100 immediate-release formulation of carbidopa/levodopa, it is typically begun with a dose of one-half to 1 tablet 3 times daily. I prefer starting with whole-tablet doses because these are usually well tolerated and quicker to achieve the goal.

The treatment goal is to capture the best levodopa response, and specifically the dose that allows the patient to be active and fully life-engaged, including exercise. With that in mind, carbidopa/levodopa can be increased weekly by half-tablet increments of all doses. The goal, as the doses are increased, is reversal of parkinsonism, sufficient to allow patients to function as normally as possible in all aspects of their life. The point of diminishing returns with dose increments is 2.5 tablets each dose for most PD patients; however, occasional patients require 3 tablets each dose for the best effect (provided that the 25/100 formulation is taken on an empty stomach). In other words, higher individual doses, such as 4 to 5 tablets at a time, provide no incremental improvement. Restated, the optimum individual dose is between 1 and 3 tablets and in early PD is taken 3 times daily.

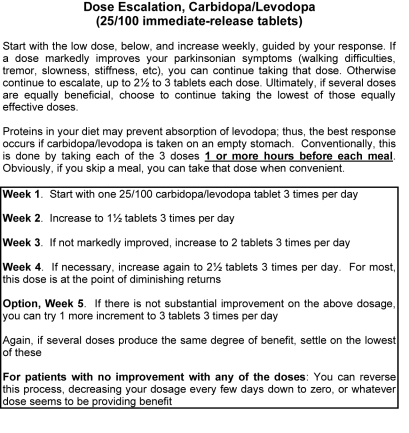

It is reasonable to allow the newly treated PD patient to increase the dose to 3 tablets 3 times daily and then decide which dose works best. If several doses are equally beneficial, the lowest of those equipotent doses can be maintained. A standard patient handout outlining this dose escalation scheme is shown in the Figure (which may be copied for distribution to individual patients). Follow-up is appropriate, typically about 6 to 8 weeks after initiating carbidopa/levodopa, to identify the maintenance dose and address any adverse effects.

FIGURE.

Example of a patient handout, outlining carbidopa/levodopa initiation and escalation.

Notably, some PD symptoms respond to carbidopa/levodopa in an “all-or-none” fashion. For example, rest tremor may not resolve with the lower doses on this schedule but may be controlled as higher doses are taken. Hence, patients should not become discouraged and abandon the scheme if the initial doses are not effective.

8. EArly Levodopa Adverse Effects Primarily Relate to Nausea and Orthostatic Hypotension

Carbidopa/levodopa typically has only limited adverse effects as it is initiated. As mentioned previously, severe nausea is uncommon, and mild nausea usually abates with continued treatment. When nausea is provoked by carbidopa/levodopa, it is due to the premature conversion of levodopa to dopamine in the bloodstream. Circulating dopamine does not cross the blood-brain barrier, except for limited regions and notably the brainstem chemoreceptive trigger zone; this is the substrate for nausea. Hence, such nausea is not a sign of gastrointestinal pathology, such as gastritis or ulcers.

Obviously, levodopa-related nausea should not be treated with centrally acting dopamine-blocking drugs such as metoclopramide or prochlorperazine. Medication options for nausea include supplementary carbidopa (Lodosyn [Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ], 25 mg), 1 to 2 tablets administered with each dose of carbidopa/levodopa. Trimethobenzamide and ondansetron are antiemetics that can be administered to PD patients because these agents do not block dopamine receptors; however, they are not highly efficacious in this setting. Outside the United States, domperidone is available; it blocks dopamine receptors but does not cross the blood-brain barrier.

Parkinson disease is associated with variable degrees of dysautonomia, and hence there is potential for orthostatic hypotension. This may be primed by drugs already on patients’ medication lists, such as antihypertensives, α1 blockers for prostatism (eg, tamsulosin), or diuretics. Obtain the standing blood pressure before starting carbidopa/levodopa, and if it is less than 100 mm Hg systolic, defer starting the drug until this is addressed. Patients with initially low-normal blood pressure should be advised to monitor their pressure as carbidopa/levodopa doses are increased; systolic values should be maintained above 90 mm Hg.

9. Levodopa Pharmacodynamics Change After Several Years: The Short-Duration Response

During the first several years of PD, the response to levodopa is stable and unvarying throughout the course of the day. This is termed the long-duration response, taking a week or 2 to slowly develop after a dose change.15,21 However, after several years, part of the benefit becomes time-locked to each dose, characterized as the short-duration response.15 Typically, patients then complain about response fluctuations. For example, they may have difficulty initially walking in the early morning, only to experience normalization an hour or so after their first morning carbidopa/levodopa dose. This benefit then fades after a few hours, with recurrence of gait problems. These short-duration responses may last from 1 to 6 hours. Patients may be oblivious to these temporal fluctuations, reporting only that they generally “can’t walk,” while overlooking the fact that parkinsonism may be well controlled during major portions of the day.

Short-duration levodopa responses rarely benefit from higher individual levodopa doses; increasing the dose does not translate into substantially longer responses. The appropriate strategy is to determine the duration of the response and adjust the dosing intervals to match the response duration. Clinicians are sometimes instructed to reduce individual levodopa doses if administering carbidopa/levodopa more frequently; however, this is not an advisable strategy. The carbidopa/levodopa dose should be the one that produces the most benefit. The number of doses or tablets per day is not important, as long as they are appropriate to the patient’s needs.

10. Levodopa Dyskinesias Are Often Benign and Treatable

Around the same time that the short-duration levodopa responses become apparent, patients may experience hyperkinetic movements, primarily manifest as chorea; these are termed dyskinesias. Just as too little brain dopamine translates into motor slowness, too much dopamine results in excessive movements, ie, dyskinesias.

Because dyskinesias represent an excessive response to dopamine replenishment, they can be abolished by reducing the individual doses of carbidopa/levodopa. Note that dyskinesias are tied to the most recent dose; thus, carbidopa/levodopa doses taken more than 6 hours previously have lost this dyskinesia potential.

Dyskinesias in this sense are manifest as predominant chorea, characterized by nonpatterned flowing or dancing movements of a limb, trunk, head/neck, or combinations of body areas. This differs from simple dystonia, which is often painful, like cramps. Pure dystonia, especially if painful, typically represents a levodopa-underdosed state, rather than an excessive levodopa effect. A common example is the dystonic toe curling or foot inversion often experienced by PD patients, reflecting wearing-off of the levodopa effect, or inadequate levodopa.

Unfortunately, reduction of levodopa to abolish dyskinesias may result in reemergence of parkinsonism. Some patients have a narrow therapeutic window between necessary and excessive levodopa effects. For such patients, the old drug amantadine works well to attenuate dyskinesias. If levodopa adjustments cannot control dyskinesias without inducing unacceptable parkinsonism, then the addition of 100 mg of amantadine twice daily is worth considering. It can be increased to 3 and then 4 times daily if necessary (dose-related response). In susceptible individuals, amantadine may contribute to confusion or hallucinations, but it is tolerated in most PD patients. It commonly causes livedo reticularis, but this is not concerning.

11. Anxiety, Akathisia, and Panic Are Common in PD and Are Levodopa-Responsive

Symptoms of PD extend well beyond motor problems. Thus, anxiety, restlessness, and even panic may reflect inadequate dopamine replenishment. Some patients may experience these as the most troublesome components of their condition. As mentioned previously, certain PD symptoms respond in an all-or-none fashion, and anxiety typically behaves that way. Waxing and waning anxiety that develops after PD onset often reflects levodopa “off” states and requires adjustment of the dosing interval.

12. Insomnia in PD Often Responds to Levodopa

Commonly, PD patients develop difficulty initiating sleep or staying asleep due to such parkinsonian symptoms as akathisia, stiffness (rigidity), inability to turn in bed, and tremor. Such insomnia typically responds to dopamine replenishment with carbidopa/levodopa. Among patients with recent-onset PD with a long-duration levodopa effect, daytime doses of carbidopa/levodopa may adequately treat insomnia. Among patients with short-duration levodopa responses, bedtime or nighttime levodopa doses will be necessary. Note that insomnia is a symptom that typically completely responds, or not at all. Hence, whatever dose has been identified as optimal for daytime use should be the same dose used at night.

Parenthetically, not all PD-related sleep disorders are linked to dopamine deficiency. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder is a primary symptom of Lewy body disorders,22 manifest as acting-out dreams. It may precede PD by many years23 and is treated with a bedtime dose of a benzodiazepine (clonazepam).

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Use of Pramipexole, Ropinirole, Selegiline, Rasagiline, or Entacapone

Among seniors, if the primary care physician is proficient with the use of carbidopa/levodopa, this agent will typically be sufficient, well into the course of PD. Proper use of carbidopa/levodopa is fundamental to PD treatment. If it seems appropriate to add another drug, this would be a good time to engage a neurology specialist.

Other, Nondopaminergic Problems Occurring in PD

Obviously, PD may be complicated by dementia, dysautonomia, osteoporosis risk, and depression. Other diagnostic strategies and treatment options are then appropriate, many of which can easily be utilized by primary care clinicians. Although these topics are beyond the scope of this article, they are comprehensively covered in 2 books written to complement one another, one for clinicians24 and a parallel book for patients,25 available in libraries.

CONCLUSION

Parkinson disease is common in seniors being cared for by primary care physicians and internists. A good working knowledge of carbidopa/levodopa will enable such clinicians to effectively care for these patients. The guidelines provided in this article will help clinicians optimize the treatment of seniors with PD.

Supplementary Material

On completion of this article, you should be able to (1) formulate an initial medication plan for patients with Parkinson disease, (2) understand the rationale for treating levodopa-associated motor fluctuations and dyskinesias, and (3) generate a reasonable treatment strategy for patients with Parkinson disease who have anxiety or insomnia.

Footnotes

Dr Ahlskog has no conflicts of interest to disclose, apart from citation of 2 books he authored on Parkinson disease.

A question-and-answer section appears at the end of this article.

Questions About Parkinson Disease Treatment

1. Which one of the following statements about Parkinson disease (PD) treatment is true?

Medications should be deferred when possible, saving the best responses for later

Dopamine agonist medications have similar efficacy to carbidopa/levodopa

Anxiety in the context of PD usually reflects an excessive levodopa effect

Dopamine agonist drugs (ropinirole, pramipexole) may cause pathological hypersexuality, eating, or shopping

It is usually initiated with amantadine

2. Which one of the following is most appropriate regarding carbidopa/levodopa?

It should be administered with meals

It is best started using the controlled-release formulation

It may provoke orthostatic hypotension

It should be limited to no more than 4 doses daily

It should not be started until other PD drugs have been tried

3. In the setting of PD, which one of the following statements about insomnia is true?

It is aggravated by bedtime doses of carbidopa/levodopa

It may be treated with half doses of carbidopa/levodopa at bedtime

It is best treated with zolpidem

It may be treated with a dose of carbidopa/levodopa before bedtime and if necessary, another dose during the night

It is caused by rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

4. Which one of the following best describes levodopa-induced dyskinesias?

Levodopa dyskinesias manifest as predominant chorea

They reflect the total daily levodopa dose

They are typically aggravated by amantadine

The risk is highest among seniors

Levodopa dyskinesias are often more disabling than the symptoms of PD

5. Which one of the following is most appropriate regarding carbidopa/levodopa treatment of seniors with PD?

The dose should be kept as low as possible

If possible, the dose should be increased sufficiently to allow exercise

It should be deferred until dopamine agonist drugs have first been administered

It may cause ulcers

It tends to raise blood pressure

This activity was designated for 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM

Because the Concise Review for Clinicians contributions are now a CME activity, the answers to the questions will no longer be published in the print journal. For CME credit and the answers, see the link on our Web site at mayoclinicproceedings.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Suchowersky O, Gronseth G, Perlmutter J, Reich S, Zesiewicz T, Weiner WJ. Practice parameter: neuroprotective strategies and alternative therapies for Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;66:976–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, et al. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1268–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahlskog JE, Uitti RJ. Rasagiline, Parkinson neuroprotection, and delayed-start trials: still no satisfaction? Neurology. 2010;74:1143–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Savica R, Rocca WA, Ahlskog JE. When does Parkinson disease start? Arch Neurol. 2010;67:798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahlskog JE. Challenging conventional wisdom: the etiologic role of dopamine oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rascol O, Brooks D, Korczyn AD, et al. A five-year study of the incidence of dyskinesia in patients with early Parkinson’s disease who were treated with ropinirole or levodopa. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1484–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parkinson Study Group Pramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:1931–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frucht S, Rogers JD, Greene PE, Gordon MF, Fahn S. Falling asleep at the wheel: motor vehicle mishaps in persons taking pramipexole and ropinirole. Neurology. 1999;52:1908–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hassan A, Bower JH, Kumar N, et al. Dopamine agonist-triggered pathological behaviors: surveillance in the PD clinic reveals high frequencies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:260–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahlskog JE, Muenter MD. Frequency of levodopa-related dyskinesias and motor fluctuations as estimated from the cumulative literature. Mov Disord. 2001;16:448–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumar N, Van Gerpen JA, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE. Levodopa-dyskinesia incidence by age of Parkinson’s disease onset. Mov Disord. 2005;20:342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Gerpen JA, Kumar N, Bower JH, Weigand S, Ahlskog JE. Levodopa-associated dyskinesia risk among Parkinson disease patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1990. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quinn N, Critchley P, Marsden CD. Young onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1987;2:73–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muenter MD, Tyce GM. L-dopa therapy of Parkinson’s disease: plasma l-dopa concentration, therapeutic response, and side effects. Mayo Clin Proc. 1971;46:231–239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muenter MD, Ahlskog JE. Dopa dyskinesias and fluctuations are not related to dopa treatment duration. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:464 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahlskog JE. Parkinson’s disease: does vigorous exercise have a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson’s disease? Neurology. 2011;77:288–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yeh KC, August TF, Bush DF, et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of Sinemet CR: a summary of human studies. Neurology. 1989;39:25–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahlskog JE, Muenter MD, McManis PG, Bell GN, Bailey PA. Controlled-release Sinemet (CR-4): a double-blind crossover study in patients with fluctuating Parkinson’s disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:876–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stocchi F, Rascol O, Kieburtz K, et al. Initiating levodopa/carbidopa therapy with and without entacapone in early Parkinson disease: the STRIDE-PD study. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:18–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hauser RA, Koller WC, Hubble JP, Malapira T, Busenbark K, Olanow CW. Time course of loss of clinical benefit following withdrawal of levodopa/carbidopa and bromocriptine in early Parkinson’ s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15:485–489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Olson EJ, et al. Insights into REM sleep behavior disorder pathophysiology in brainstem-predominant Lewy body disease. Sleep Med. 2007;8:60–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Silber MH, Tippmann-Peikert M, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology. 2010;75:494–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahlskog JE. Parkinson’s Disease Treatment Guide for Physicians. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009:382 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahlskog JE. The Parkinson’s Disease Treatment Book: Partnering with Your Doctor to Get the Most from Your Medications. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005:532 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.