Abstract

Marital distress is linked to many types of mental disorders; however, no study to date has examined this link in the context of empirically-based hierarchical models of psychopathology. There may be general associations between low levels of marital quality and broad groups of comorbid psychiatric disorders as well as links between marital adjustment and specific types of mental disorders. The authors examined this issue in a sample (N=929 couples) of currently married couples from the Minnesota Twin Family Study who completed self-report measures of relationship adjustment and were also assessed for common mental disorders. Structural equation modeling indicated that a) higher standing on latent factors of internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) psychopathology was associated with lower standing on latent factors of general marital adjustment for both husbands and wives, b) the magnitude of these effects was similar across husbands and wives, and c) there were no residual associations between any specific mental disorder and overall relationship adjustment after controlling for the INT and EXT factors. These findings point to the utility of hierarchical models in understanding psychopathology and its correlates. Much of the link between mental disorder and marital distress operated at the level of broad spectrums of psychopathological variation (i.e., higher levels of marital distress were associated with disorder comorbidity), suggesting that the temperamental core of these spectrums contributes not only to symptoms of mental illness but to the behaviors that lead to impaired marital quality in adulthood.

A substantial body of research now supports the association between marital distress and psychopathology (Whisman, 2007; Whisman & Bruce, 1999; Whisman, Uebelacker, Tolejko, Chatav, & McKelvie, 2006b; Whisman, Uebelacker, & Weinstock, 2004). For instance, there is a robust and well-replicated association between marital discord and major depression; a meta-analysis of 26 cross-sectional studies found an effect size of .42 for women and .37 for men (Whisman & Uebelacker, 2003). Low levels of marital satisfaction have also been linked with anxiety disorders (Markowitz, Weissman, Ouellette, Lish, & Klerman, 1989; McLeod, 1994), alcohol use disorders (Homish & Leonard, 2007; Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Whisman, Uebelacker, & Bruce, 2006a), drug use disorders (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, & O'Farrell, 1999; Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius, 2008; Newcomb, 1994), and personality disorders (South, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2008; Whisman & Schonbrun, 2009).

Of note, even though many different clinical disorders show substantial rates of comorbidity (Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001; Dolan-Sewell, Krueger, & Shea, 2001; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005b), or non-random overlap that cannot be explained by chance alone (Lilienfeld, Waldman, & Israel, 1994), research examining associations between marital distress and psychopathology rarely addresses how comorbidity might affect these links. In one exception, Whisman (1999) used the National Comorbidity Survey sample to compare associations between 13 different disorders and marital dissatisfaction, both before and after covarying for presence of other disorders. Without covarying for comorbidity, marital discord was related to 7 of 12 specific disorders for women and 3 of 13 disorders for men; only depression and PTSD (for women) and dysthymia (for men) were significantly associated with marital distress after partialling out other disorders. Similarly, the association between anxiety and marital distress is lessened (Whisman, et al., 2004) or non-significant (Uebelacker & Whisman, 2006) when depressive symptoms are included in the model. South and colleagues (2008) found support for significant associations between marital adjustment and overall levels of personality disorder (PD) symptoms, but few unique associations with symptoms of specific PDs, possibly because they partialled out all other PD symptoms when examining each disorder individually. Thus, while the literature on comorbidity and marital satisfaction is somewhat more limited, it suggests that comorbidity is an important factor in understanding how mental disorders are connected to marital distress.

The present study builds on this prior research by examining the specificity and generality of relations between marital distress and different types of mental disorders. Instead of attempting to covary the effects of clinical disorders to examine unique associations, we utilize Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), which has the advantage of minimizing the impact of bias due to unreliability and thus reducing Type I error rate (Zinbarg, Suzuki, Uliaszek, & Lewis, 2010b). We frame our research in light of a dimensional-spectrum model of clinical disorders (Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Krueger, 1999; Krueger & Markon, 2006). A spectrum model explains the high levels of comorbidity among different mental disorders as a function of the way disorders are empirically connected. With regard to common mental disorders, phenotypic and behavior genetic research supports the existence of two latent dimensions: an Internalizing (INT) factor, which subsumes two lower-order factors of Distress (major depression, generalized anxiety) and Fear (phobias, panic attack); and a latent Externalizing (EXT) factor indicated by substance use disorders, conduct disorder, and adult antisocial behavior (Griffith, et al., 2010; Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott, & Kendler, 2006; Kendler, et al., 2003; Krueger, 1999; Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998; Krueger, et al., 2002; Prenoveau, et al., 2010; South & Krueger, 2008; Vollebergh, et al., 2001).

Given this model, in which different types of clinical disorders are understood as being linked to shared underlying temperamental antecedents (Clark, 2005; Zinbarg, et al., 2010a), a potentially useful analysis would consider and model both general and specific connections between mental disorders and marital distress. Marital distress is certainly a correlate of specific forms of psychopathology (Beach, Katz, Kim, & Brody, 2003; Overbeek, et al., 2006; Whisman, 2007; Whisman & Bruce, 1999; Whisman, et al., 2006a). Low levels of marital satisfaction have also been linked to broader classes of disorders, including mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (Whisman, 1999, Whisman, 2007). In a recent study, Humbad and colleagues (2010) found that both individual externalizing syndromes (i.e., conduct disorder, antisocial behavior, substance use) and a composite of these various syndromes were negatively related to marital adjustment, suggesting that externalizing psychopathology per se is an individual vulnerability to marital distress. Left unanswered in that study was the question of whether marital dysfunction was attributable to whatever is shared in common between externalizing disorders, or if each syndrome has unique and specific effects on the marital relationship after accounting for overall levels of externalizing pathology.

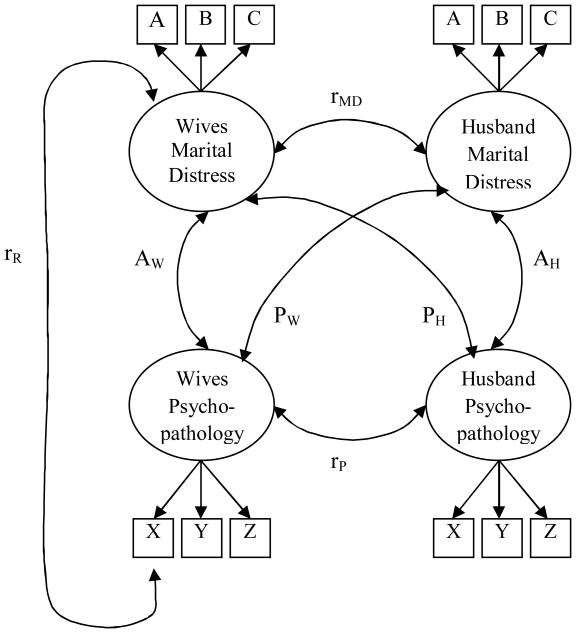

Thus, we do not yet know if marital discord is linked to the general INT and EXT domains, the residual aspects of certain forms of INT and EXT psychopathology, or a combination of both general and specific relations. Figure 1 presents a simplified model of the full set of associations estimated in the current study. Our first research question is whether common forms of psychopathology, which have individually been linked to martial distress previously, can be modeled as higher order factors which are associated with marital adjustment. As shown, observed indicators X, Y, and Z (e.g., depression, anxiety, social phobia) may be related to marital distress through latent factors of psychopathology.

Figure 1.

Simplified model outlining pathways between latent factors representing wives' and husbands' psychopathology and marital distress. Marital distress factors were comprised of subscales from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale, represented here as observed indicators A, B, and C. Psychopathology factors were comprised of symptom count variables of major forms of psychopathology (e.g., major depression, anxiety, social phobia), here represented as observed indicators X, Y, and Z. AW and AH represent wives' and husbands' actor effects, respectively (i.e., association of wives' psychopathology and wives' own marital distress); PW and PH represent wives' and husbands' partner effects, respectively (i.e., association between wives' psychopathology and husbands' marital distress); rMD represents the covariance between wives' and husbands' marital distress; rP represents the covariance between wives' and husbands' psychopathology; rR represents the covariance between marital distress and the residual variance of one observed indicator of psychopathology.

Also shown in Figure 1, there are paths from the psychopathology factors for both husbands and wives to both self- and spouse's marital adjustment factor. Kenny and colleagues (Kenny, 1996; Snjiders & Kenny, 1999) have articulated the distinction between actor effects and partner effects. An actor effect is the influence of the target's own behavior on their own satisfaction (e.g., wife's depression affecting her own satisfaction), while the partner effect is the influence of one's spouse on own satisfaction (e.g., husband's depression affecting wife's rating of satisfaction). Most research in this area has focused only on actor effects, whether in large community epidemiologic research (e.g., Whisman, 1999) or treatment samples in which the patient often reports lower levels of marital satisfaction (e.g., Fals-Stewart, et al., 1999). By incorporating measures of self- and spouse-report of psychopathology and marital distress, it is possible to estimate directly the importance of spouse's mental health on one's own marital satisfaction, as well as statistically covarying for the fact that couples are often correlated on level of psychopathology (i.e., assortative mating is present for many clinical disorders; Galbaud du Fort, Boothroyd, Bland, Newman, & Kakuma, 2002; Butterworth & Rodgers, 2006; Low, Cui, & Merikangas, 2007). Empirical work to date has found support for actor effects of anxiety (Whisman, et al., 2004), actor and partner effects of depression (Whisman & Uebelacker, 2009; Whisman, et al., 2004), and actor and partner effects of personality disorder symptoms (South, et al., 2008) on marital satisfaction. Our second research question was to estimate actor effects between wives' and husbands' own level of INT/EXT psychopathology and own marital distress (AW and AH in Figure 1), as well as wives' and husbands' own psychopathology and spouses' marital distress (PW and PH in Figure 1). Also directly estimated were the associations between wives' and husbands' marital distress (rMD) and assortative mating for the latent psychopathology factors (rP).

Finally, Figure 1 also includes a pathway from the marital distress factor to the residual variance of a psychopathology indicator, an example of understanding the connections between specific aspects of psychopathology and the latent construct of marital adjustment. Previous work has examined associations between more narrow-band forms of psychopathology and marital distress while covarying out comorbid disorders; however, there has been no work to date to examine whether there are associations between marital adjustment and whatever is unique to different types of psychopathology after accounting for the broader spectrums that link these disorders together. Finding significant associations between an overall marital adjustment factor and the residual variances of the clinical disorders subsumed by our latent INT and EXT factors (i.e., the residual correlation, rR, found in Figure 1) would provide tentative evidence of specificity in the transactions between psychopathology and the marital relationship. Conversely, the lack of such associations would suggest that marital distress in the presence of psychopathology may be a function of the impairment caused by the temperament and/or behaviors at the core of the internalizing and externalizing spectrums.

Current Study

In the current study, we extend previous research by directly modeling the comorbidity between clinical disorders and their associations with marital distress. The simplified model in Figure 1 was expanded to include latent INT and EXT factors for both wives and husbands. Based on previous research, we expected both INT and EXT psychopathology to be negatively related to self-reported marital adjustment. We also predicted that the size of the associations between marital adjustment and psychopathology would be similar across husbands and wives (i.e., estimates for AW and AH and PW and PH in Figure 1 would be of similar magnitude). While we fully expected that the higher-order factors of INT and EXT would be significantly related to marital distress in husbands and wives, our aim was to determine if this association is driven by the shared variance between the predictors within the respective factors (e.g., the overall extent of comorbidity in the internalizing spectrum), or if each clinical syndrome (e.g., depression) also has its own unique links to marital distress. Thus, we explored whether any specific associations exist between the clinical disorders and marital satisfaction after accounting for the broader INT and EXT factors by estimating correlations between residual variances of the observed indicators of the psychopathology factors and the marital adjustment latent factor (as shown by the rR correlation in Figure 1). These research questions have important implications for our understanding of clinical predictors of marital distress, as they may help in building a coherent account of the impact of both comorbidity and the distinctions among specific mental disorders on marital functioning.

Method

Participants

The current sample consisted of husbands and wives who participated in the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), a longitudinal, epidemiological study investigating the development of substance use and related disorders. The initial MTFS sample consists of two parallel cohorts of same-sex twin pairs reared by their biological parents, one initially assessed at age 11 years (the younger cohort) and one initially assessed at age 17 years (the older cohort). Twin births for the years 1972 to 1984 were identified using Minnesota state birth records, and using publicly available data bases (e.g., phone books, Internet directories), we located addresses for over 90% of those twins still alive and invited them to participate in a study of the maturation and health of twins. Female twins and their parents attended intake in 1993-1996 (both cohorts), while male twins and their parents visited the study for intake assessment from 1990-1994 (11 year old cohort) and 1990-1995 (17 year old cohort). Of the eligible families recruited for the study in this manner, 17.3% declined participation. In 2000, the MTFS began recruitment of an Enrichment Sample (ES) to increase the number of twins at high risk for the development of substance use problems by virtue of at least one twin having a childhood disruptive disorder (Keyes, et al., 2009). ES participants were ascertained from Minnesota birth records of 2717 like-sex twin pairs born between 1988 and 1994; 82% of identified births (2226 total pairs; 1073 male and 1153 female) were successfully located and recruited to participate in our study in the year they turned 11. Of those who were eligible to visit, 75% attended the assessment. The final ES sample consisted of 499 twin pairs, 48% drawn from screenings designed to recruit twins meeting a pre-determined threshold for symptoms of externalizing disorders, and the rest drawn from recruitment procedures that paralleled the MTFS twin recruitment. For both the original two cohorts and the ES cohort, exclusion criteria included: either twin had a physical or intellectual disability that precluded completing the daylong, in-person assessment, the family lived more than a day's drive from Minneapolis, or the twins had been adopted. A thorough explanation and rationale for the study was provided to all participants, and written informed assent/consent was obtained. More detailed information on the recruitment and design of the MTFS can be found elsewhere (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999).

For the current analyses, we utilized data from the biological mothers and fathers of twins from both the original age 11 and age 17 female cohorts and the total enrichment sample. Mothers and fathers of the age 11 and age 17 original male cohorts were eliminated from the analyses because they were assessed only on a subset of the clinical disorders. We included all biological parents who were married to each other and completed the DAS inventory at the intake assessment (i.e., stepparents were excluded). Length of marriage (M=16.4 years, SD=4.1, Range=2-31) was available on a subset (N= 379) of the couples. While data was unavailable on the rest of the sample, by definition these were relatively long-term relationships/marriages (i.e., couples had to survive intact until their children reached either 11 or 17 years old). The final sample consisted of 929 couples in which at least one parent participated in the assessment1; this included 378 couples from the ES sample, 298 couples from the younger (age 11) cohort, and 253 couples from the older (age 17) cohort. Wives ranged in age from 29 to 60 (M = 42, SD = 5.1) and husbands ranged in age from 30 to 65 (M = 44, SD = 5.6). The racial-ethnic make-up of the sample was predominantly Caucasian (97%), consistent with Minnesota demographics for the birth years sampled.

Measures

Clinical assessment

All participants attended day-long in-person assessments in the MTFS offices at the University of Minnesota. Participants were interviewed separately by different interviewers to assess lifetime mental disorders according to criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edition, revised; DSM–III–R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987), the diagnostic system in place at the time of intake. ES parents were assessed for disorders according to both DSM-III-R and DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria; in order to combine samples, DSM-III-R symptom counts are used in the current analyses. Structured clinical interviews were conducted by trained staff, all of whom had either a bachelor's or master's degree in psychology and went through extensive training and observation. Interview data were then reviewed in a case conference by at least 2 advanced clinical psychology graduate students. The diagnosticians had to reach a consensus regarding the presence or absence of a symptom before it was assigned, referring to audiotapes of the interview when necessary. The consensus process yielded uniformly high diagnostic reliabilities (e.g., .92 or greater for all substance use disorder diagnoses; Iacono, 1999). Parents were assessed for lifetime history of all clinical disorders at the intake assessment.

The current analyses included symptom count variables of five DSM-III-R disorders generally included in the externalizing spectrum: adult antisocial behavior, conduct disorder, alcohol dependence, nicotine dependence, and illicit drug dependence. A modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis II Personality Disorders (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1997) was used to assess adult antisocial behavior (i.e., the adult criteria for antisocial personality disorder). Substance use disorders were assessed using the Substance Abuse Module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins, et al., 1988). The interview assessed symptoms of drug abuse and dependence for the following illicit drugs: amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, phencyclidine, and sedatives. If a participant endorsed more than one drug class, number of dependence symptoms was based on the drug class for which the participant endorsed the most symptoms. As the diagnostic system was DSM-III-R, symptoms of abuse were included in the alcohol and drug dependence symptom count variables. Also included in the current analyses were symptom count variables for five DSM-III-R disorders in the internalizing spectrum: major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, simple phobia, and social phobia. Symptoms for these five disorders were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbon, 1987).

Marital satisfaction

Participants reported on their marital satisfaction by completing the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976) regarding their current marriage. Administration of the DAS for the current study departed slightly from standard administration by asking participants to report on their relationship over the preceding 12 months. The DAS is one of the most widely used measures of relationship satisfaction in the social sciences. Spanier originally identified four subscales of the DAS. Satisfaction (10 items; e.g., How often do you and your partner quarrel?) assesses aspects related to perceived stability of the marriage and how fights are handled. Consensus (13 items; e.g., Handling family finances) measures the degree to which couples agree or disagree on a number of issues. Cohesion (5 items; e.g., Do you and your mate engage in outside interests together?) measures the frequency of positive interactions between the couple. Affectional Expression (4 items; e.g., Demonstrations of affection) assesses the degree of agreement on how affection is expressed. Previous analyses of the DAS in the larger MTFS sample confirmed a hierarchical factor structure in which four lower-order factors, corresponding to the DAS subscales, were overlaid by one, higher-order factor of relationship adjustment (South, Krueger, & Iacono, 2009). Alpha coefficients for the current sample were: .93 (DAS total), .87 (Satisfaction), .88 (Consensus), .83 (Cohesion), .74 (Affectional Expression) for wives, and .93 (DAS total), .87 (Satisfaction), .87 (Consensus), .79 (Cohesion), .73 (Affectional Expression) for husbands. Omegahierarchical, a measure of how strongly scale scores are influenced by a latent variable common to all indicators (Zinbarg, Revelle, & Yovel, 2007; Zinbarg, Yovel, Revelle, & McDonald, 2006), where scores range from 0 to 1 and scores closer to one indicate greater general factor saturation, was .78 for wives and .77 for husbands.

Analytical Approach

We used structural equation modeling in Mplus (Muthén, 1998-2007) to test the associations between latent factors of psychopathology and latent factors of marital adjustment for husbands and wives. As shown in Figure 1, paths were included to model the associations between one's own psychopathology and own marital distress (AW for wives and AH for husbands), as well as between own psychopathology and partner's marital distress (PW and PH). Spousal correlations between psychopathology (rP) and marital distress (rMD) were also included. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in Mplus using raw data in the form of symptom count variables for major depression (MD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), simple phobia (SiP), social phobia (SoP), adult antisocial behavior (AAB), alcohol dependence (AD), drug dependence (DD), nicotine dependence (ND) and conduct disorder (CD).

Symptom counts have been used frequently in confirmatory factor modeling of the structure of psychopathology (Krueger, et al., 2002; Markon, 2010) instead of item-level symptom endorsement or presence/absence of the disorder for several reasons (c.f., Krueger, et al., 2002). First, symptom count variables have greater statistical power in community-based samples like the MTFS, which have lower diagnostic prevalence rates compared with clinic-ascertained samples. Second, there is growing evidence that many psychopathology variables are well conceptualized as dimensional, rather than categorical, concepts (Markon, 2010, Markon & Krueger, 2005). Applying a categorical threshold to dimensional concepts can result in a loss of information (Brown, DiNardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). Third, item-level indicators pose several psychometric challenges, including lower reliability, greater potential for sampling error, and more complex (less parsimonious) models (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). Finally, even though symptom count variables preclude the identification of common factors at the disorder level, symptom-level analyses generally support the symptom clusters as found in the DSM (e.g., Prenoveau, et al., 2010). Due to low endorsement frequencies, the PD and GAD variables were truncated; values of PD over nine symptoms were collapsed into the nine category for a total of 10 (0-9 symptoms) possible responses, while GAD was collapsed into a two-level variable (5 symptoms or below endorsed, more than 5 symptoms endorsed)2. Scores for the DAS subscales of Satisfaction, Consensus, Cohesion, and Affectional Expression were created by summing the scores for the raw items according to each scale.

First, a baseline model was estimated to confirm 1) the INT-EXT factor structure using clinical disorder symptom count variables, and 2) a marital adjustment factor using the four DAS subscale scores as indicator variables. This model estimated correlations between the two DAS latent factors, as well as the six correlations between the four INT/EXT latent factors; it did not include any actor or partner effects between DAS and INT/EXT. Also included in the model were residual correlations between the DAS indicators across husbands and wives (e.g., residual error of Satisfaction for wives was correlated with residual error of Satisfaction for husbands), to account for any shared residual variances between husbands and wives on these specific aspects of marital adjustment. After establishing the baseline measurement model, we added the actor and partner effects in the form of bidirectional, two-headed paths (i.e., correlations) between the INT and EXT factors and the DAS factors for husbands and wives. Having determined that a model including actor and partner effects between psychopathology and marital satisfaction improved the fit of the model, we then tested the equivalence of these associations across gender by holding actor and partner effects constant across husbands and wives. This model was an expanded version of the model shown in Figure 1. Finally, we examined the relationships between the DAS factors and residual scores of each of the observed indicators of the INT and EXT factors.

To take into account the skewed nature of the symptom count data, the model was fit using the weighted least-square-mean variance adjusted estimator (WLSMV; weighted least-square parameter estimates with a diagonal weight matrix, robust standard errors, and a mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square test statistic). Symptom count variables were treated as ordered-categorical while DAS scale scores were treated as continuous. Missing data were handled using the default option in Mplus, which estimates models under missing data theory using all available data (Muthén, 1998-2007), a procedure that produces more reliable inferences when compared with other options (e.g., listwise deletion) for missing data (Enders, 2001). Overall goodness of fit of the model was evaluated using root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Hu and Bentler (1999) recommend the following values for acceptable model fit: RMSEA close to or less than .06, and CFI and TLI close to or greater than .95. They specifically used the language “close to” because these recommended cutoff values fluctuate as a function of model conditions and whether they are used alone or in conjunction with other fit indices (see Brown, 2006 for further discussion of goodness-of-fit indices). Chi-square difference testing was conducted with the DIFFTEST option in Mplus. With the WLSMV estimator, interpretation should only be based on the p values of the DIFFTEST results; if the p value is less than .05, the more restrictive model significantly worsens the fit of the model to the data, while if the p value is greater than .05, the more restrictive model does not significantly worsen the fit of the model.

Results

Correlations between the study variables, means for the symptom count variables and DAS scale scores, and percentage of the sample meeting diagnostic thresholds are presented separately by gender in Table 1. The significant inter-correlations among the symptom count variables strongly suggested the presence of a latent externalizing factor for both husbands and wives. There were fewer significant associations among the mood and anxiety disorder symptom count variables, although the moderate, significant correlations between MD and GAD, and SiP and SoP, respectively, map onto two distinct sub-factors of internalizing pathology. Symptom count and duration of symptoms were used to assign diagnoses according to DSM-III-R guidelines; 65.6 % of husbands met criteria for at least one disorder, the most prevalent being nicotine dependence at 35.8%, while 57% of wives met criteria for at least one disorder, with nicotine dependence (25.2%) followed closely by major depressive disorder (24.2%). In line with previous research, there was evidence of assortative mating or of mated partners becoming similar to each other after marriage, as indicated by significant correlations between husbands and wives on several variables. Substance use and adult antisocial behavior, in particular, showed a great degree of overlap between spouses.

Table 1. Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Marital Adjustment and Disorder Symptom Counts.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MD | .13 | .09 | .28 | .02 | .10 | .15 | .12 | .06 | .14 | .11 | −.18 | −.19 | −.16 | −.12 | −.17 |

| 2 | GAD | .13 | −.02 | .06 | .01 | .05 | .04 | .03 | .04 | .04 | .05 | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | −.002 | .01 |

| 3 | PD | .25 | .15 | .04 | .07 | .14 | .04 | .08 | .02 | .12 | .07 | −.08 | −.07 | −.05 | −.03 | −.09 |

| 4 | SiP | .04 | .03 | −.03 | .10 | .35 | −.02 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .02 | .04 | −.01 | .05 | .03 |

| 5 | SoP | .05 | .00 | .05 | .23 | .17 | −.04 | .01 | .07 | .03 | .07 | −.03 | .00 | −.04 | −.01 | .00 |

| 6 | AAB | .07 | −.02 | .00 | −.01 | .02 | .21 | .31 | .38 | .40 | .29 | −.19 | −.18 | −.17 | −.07 | −.13 |

| 7 | CD | .03 | .08 | .00 | .03 | .12 | .38 | .08 | .22 | .22 | .25 | −.11 | −.11 | −.11 | .00 | −.05 |

| 8 | AD | .06 | .01 | .09 | .05 | .11 | .47 | .23 | .19 | .35 | .35 | −.07 | −.06 | −.10 | −.01 | −.05 |

| 9 | DD | .11 | −.01 | .02 | −.07 | −.03 | .48 | .26 | .40 | .25 | .26 | −.17 | −.13 | −.18 | −.04 | −.10 |

| 10 | ND | .07 | .06 | .06 | .09 | .15 | .30 | .20 | .40 | .29 | .29 | −.14 | −.08 | −.12 | −.06 | −.06 |

| 11 | DAS Total | −.12 | −.04 | −.11 | −.02 | −.09 | −.21 | −.10 | −.18 | −.11 | −.15 | .61 | .90 | .88 | .77 | .69 |

| 12 | DAS Satisfaction | −.13 | −.04 | −.09 | −.02 | −.07 | −.22 | −.08 | −.16 | −.12 | −.14 | .90 | .67 | .68 | .65 | .59 |

| 13 | DAS Consensus | −.08 | −.01 | −.08 | .01 | −.11 | −.21 | −.11 | −.19 | −.14 | −.15 | .89 | .68 | .41 | .53 | .52 |

| 14 | DAS Cohesion | −.05 | −.06 | −.07 | .01 | −.02 | −.10 | −.07 | −.13 | −.05 | −.10 | .75 | .62 | .54 | .48 | .44 |

| 15 | DAS AE | −.11 | −.05 | −.12 | .02 | −.06 | −.10 | −.04 | −.08 | −.04 | −.08 | .73 | .63 | .56 | .42 | .52 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Husbands | ||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.75 | 1.37 | 1.67 | 1.18 | 1.90 | 0.79 | 1.74 | 107.90 | 38.04 | 47.32 | 14.48 | 8.12 | |

| SD | 2.12 | 0.85 | 1.58 | 1.50 | 1.94 | 1.19 | 1.48 | 2.23 | 1.63 | 2.06 | 14.98 | 5.72 | 6.40 | 3.43 | 2.26 | |

| % meeting dx | 10.9 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 12.2 | 7.5 | 16.0 | 32.4 | 11.6 | 35.8 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Wives | ||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 1.94 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 1.43 | 1.54 | 0.81 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 1.32 | 109.29 | 37.79 | 48.25 | 14.66 | 8.35 | |

| SD | 2.83 | 1.48 | 2.59 | 1.90 | 2.00 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 1.26 | 1.09 | 1.98 | 15.75 | 6.12 | 6.88 | 3.92 | 2.33 | |

| % meeting dx | 24.2 | 1.1 | 6.6 | 11.8 | 14.9 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 8.0 | 4.1 | 25.2 | - | - | - | - | - | |

Note. N=1,824 (929 wives, 895 husbands). Bold is p<.05. Diagonal (italicized) is within-couple correlation. Wives are above diagonal, husbands are below. MD=Major Depression, GAD=Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PD=Panic Disorder, SiP=Simple Phobia, SoP=Social Phobia, AAB=Adult Antisocial Behavior, CD=Conduct Disorder, AD=Alcohol Dependence, DD=Drug Dependence, ND=Nicotine Dependence, DAS=Dyadic Adjustment Scale, AE=Affectional Expression.

As expected, DAS total score was significantly and negatively correlated with many of the symptom count variables. The DAS subscales were more heterogeneous in their associations with the symptom count variables, particularly across gender. For wives, correlations between DAS Satisfaction and Consensus subscales largely paralleled results for the total DAS score; however, DAS Cohesion and Affectional Expression were limited to significant, negative associations with MD and AAB for the former and MD, AAB, PD and DD for the latter. For husbands, DAS Cohesion was significantly negatively correlated with AAB, AD, and ND, while the other three DAS subscales showed correlations similar to the DAS total score. Typically, a DAS score of 97 and below is associated with marital distress (Jacobson, et al., 1984). Using this conventional criterion, 18.2% of husbands and 20.9% of wives in our sample were classified in the distressed range, which is lower than has been found in previous studies of married community couples (e.g., 39-49% of spouses, Heyman, Sayers, & Bellack, 1994). Agreement between husbands and wives on DAS total and subscale scores was moderate to large, ranging from from .41 (Consensus) to .67 (Satisfaction).

Model Fitting

The first step was to confirm the factor structure of the internalizing, externalizing, and marital adjustment latent factors in a baseline measurement model. Actor and partner effects were then added and constrained equal in a series of steps, and the fit of these subsequent models was compared to the baseline model to determine whether the additional parameters significantly improved model fit. For the baseline model, the symptom count variables for the clinical disorders were fit to a factor model in which AAB, AD, DD, ND, and CD were subsumed under one latent EXT factor, while a higher-order latent INT factor split into two lower-order latent factors: Distress (MD, GAD), and Fear (PD, SiP, SoP). Separate EXT, INT, Fear and Distress latent factors were fit for husbands and wives. For identification purposes, the metric of the factors was defined by setting the variance for INT, EXT, Distress and Fear to 1.0. To identify the Distress factor, the loadings for MD and GAD were set equal. The INT factor was identified by setting Distress to 1.0 and Fear to the lower-order factor correlation, which was .56 for wives and .91 for husbands (Zinbarg, Yovel, & Revelle, 2007)3. The factor loadings for the observed indicators and the error variances were freely estimated. Latent factors of relationship adjustment were fit separately for husbands and wives, consisting of the four DAS subscales as observed indicators. Again, the metric of the DAS factors was defined by setting the variance to 1.0, and the loadings for the indicators and error variances were freely estimated. The DAS factors for husbands and wives were allowed to correlate, the residual errors for the DAS indicators were correlated across husbands and wives, and the INT and EXT factor covariances were freely estimated; as this was the baseline measurement model, the covariances between the DAS factors and the INT/EXT factors was set to 0.

The baseline measurement model did not meet recommended thresholds for acceptable model fit (see Model 1, Table 2). The loadings of all indicator variables on their respective factors were significant, as was the correlation between the latent DAS factors and the residual DAS correlations for husbands and wives (see Table 3). The inter-correlations between the Husband' and Wives' INT and EXT factors were also significant, with the exception of Husband's INT and Wives' EXT (which was non-significant and removed from the model). Of note, the correlations between husbands and wives on the INT factor and EXT factor were higher than within-spouse (i.e., Wives' INT and Wives' EXT) or cross-spouse, cross-factor correlations (i.e., husband's INT and wives EXT), indicating evidence of assortative mating for these latent factors. Indeed, a model that constrained all of the INT/EXT covariances to equality resulted in significantly worse fit (DIFFTEST=33.21, p<.0001). The poor overall fit of Model 1 suggested that the addition of other parameters (i.e., actor and partner effects between the DAS and INT/EXT factors) might improve the fit of this baseline measurement model.

Table 2. Fit of Confirmatory Factor Models of INT, EXT, and Marital Adjustment (DAS).

| Model | X2 | df | DIFFTEST | Model Comparison | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Baseline measurement model | 486.57*** | 96 | -- | 0.876 | 0.873 | 0.066 | |

| Model 2: Actor and Partner effects added | 315.33*** | 118 | 114.05 (5)*** | 2 vs. 1 | 0.937 | 0.948 | 0.042 |

| Model 3: Actor and Partner effects constrained across gender | 290.80*** | 114 | 1.79 (4) | 3 vs. 2 | 0.940 | 0.950 | 0.041 |

Note. N = 1,824.

p<.001. X2= chi-square fit statistic with robust standard errors, df = degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. DIFFTEST=Chi-square difference testing for nested models was done via the difference test implemented in Mplus. Chi-square value and degrees of freedom for WLSMV do not directly correspond to the number of estimated parameters. See the Mplus Technical Appendices at www.statmodel.com or the index of the Mplus User's Guide (Muthén & Muthén, 2007) for the formula used to calculate degrees of freedom. Model 2: All actor and partner effects between INT/EXT and DAS freely estimated. Model 3: Actor and Partner effects between DAS indicators and INT/EXT indicators constrained equal across husbands and wives.

Table 3. Parameter Estimates from Confirmatory Factor Models.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wives | Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Husbands | |||||||

| DAS | ||||||||||||

| Satisfaction (S) | 5.76/0.94 | 5.29/0.93 | 5.69/0.93 | 5.27/0.92 | 5.66/0.93 | 5.30/0.93 | ||||||

| Consensus (CN) | 5.16/0.75 | 4.73/0.74 | 5.35/0.78 | 4.91/0.77 | 5.34/0.78 | 4.93/0.77 | ||||||

| Cohesion (Coh) | 2.73/0.70 | 2.38/0.69 | 2.66/0.68 | 2.35/0.69 | 2.64/0.67 | 2.36/0.67 | ||||||

| Affectional Expression (AE) | 1.50/0.64 | 1.53/0.68 | 1.47/0.63 | 1.49/0.66 | 1.47/0.63 | 1.50/0.63 | ||||||

| Distress | ||||||||||||

| Major Depression (MD) | 0.50/0.71 | 0.50/0.71 | 0.57/0.81 | 0.51/0.72 | 0.56/0.79 | 0.52/0.74 | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety (GAD) | 0.50/0.71 | 0.50/0.71 | 0.57/0.81 | 0.51/0.72 | 0.56/0.79 | 0.52/0.74 | ||||||

| Fear | ||||||||||||

| Social Phobia (SoP) | 0.60/0.69 | 0.37/0.49 | 0.51/0.59 | 0.33/0.44 | 0.50/0.57 | 0.33/0.45 | ||||||

| Simple Phobia (SiP) | 0.43/0.49 | 0.29/0.40 | 0.36/0.41 | 0.23/0.31 | 0.35/0.40 | 0.23/0.32 | ||||||

| Panic Disorder (PD) | 0.40/0.46 | 0.43/0.58 | 0.52/0.59 | 0.53/0.72 | 0.52/0.60 | 0.54/0.73 | ||||||

| INT | ||||||||||||

| Distress | 1.00/0.71 | 1.00/0.71 | 1.00/0.71 | 1.00/0.71 | 1.00/0.71 | 1.00/0.71 | ||||||

| Fear | 0.56/0.49 | 0.91/0.67 | 0.56/0.49 | 0.91/0.67 | 0.56/0.49 | 0.91/0.67 | ||||||

| EXT | ||||||||||||

| Adult Antisocial Behavior (AAB) | 0.69/0.69 | 0.74/0.74 | 0.72/0.72 | 0.74/0.74 | 0.71/0.71 | 0.74/0.74 | ||||||

| Alcohol Dependence (AD) | 0.71/0.71 | 0.70/0.70 | 0.69/0.69 | 0.70/0.70 | 0.68/0.68 | 0.71/0.71 | ||||||

| Nicotine Dependence (ND) | 0.66/0.66 | 0.59/0.59 | 0.65/0.65 | 0.60/0.60 | 0.65/0.65 | 0.60/0.60 | ||||||

| Drug Dependence (DD) | 0.82/0.82 | 0.79/0.79 | 0.82/0.82 | 0.77/0.77 | 0.82/0.82 | 0.77/0.77 | ||||||

| Conduct Disorder (CD) | 0.50/0.50 | 0.45/0.45 | 0.50/0.50 | 0.45/0.45 | 0.50/0.50 | 0.45/0.45 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Correlations and Residual Correlations | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| INT-H with EXT-W | 0.00NS | 0.00NS | 0.00NS | |||||||||

| INT-H with INT-W | 0.67/0.67 | 0.63/0.63 | 0.62/0.62 | |||||||||

| EXT-W with INT-W | 0.35/0.35 | 0.35/0.35 | 0.36/0.36 | |||||||||

| EXT-H with INT-W | 0.21/0.21 | 0.19/0.19 | 0.19/0.19 | |||||||||

| EXT-W with EXT-H | 0.55/0.55 | 0.55/0.55 | 0.55/0.55 | |||||||||

| EXT-H with INT-H | 0.31/0.31 | 0.31/0.31 | 0.30/0.30 | |||||||||

| DAS-W with DAS-H | 0.69/0.69 | 0.69/0.69 | 0.69/0.69 | |||||||||

| S-W with S-H | 2.69/0.60 | 3.06/0.61 | 3.08/0.62 | |||||||||

| CN-W with CN-H | 1.63/0.08 | 0.35NS//0.02 | 0.34NS/0.02 | |||||||||

| Coh-W with Coh-H | 2.08/0.30 | 2.25/0.31 | 2.27/0.32 | |||||||||

| AE-W with AE-H | 1.19/0.40 | 1.27/0.41 | 1.28/0.41 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Actor and Partner Effects | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| a | p | a | p | a | p | a | p | a (aw=ah) | p (pw=ph) | |||

|

|

||||||||||||

| INT | - | - | - | - | −.25 | −.25 | −.32 | −.28 | −.28 | −.26 | ||

| EXT | - | - | - | - | −.23 | −.21 | −.28 | −.19 | −.26 | −.19 | ||

Note. N = 1,824. Unstandardized estimates/standardized estimates of factor loadings, latent factor covariances, and indicator residual covariances are presented. Model 3 was fit constraining Actor (A) and Partner (P) effects equal across husbands and wives but different for INT and EXT. All coefficients are significant at p<.05 except those indicated with NS.

To examine our main hypothesis of associations between the latent factors of psychopathology and marital adjustment, we allowed freely estimated correlations between INT and EXT factors and the DAS factor for husbands and wives (see Model 2, Table 2). This model including actor and partner effects improved on Model 1; in addition to producing higher CFI and TLI and lower RMSEA, a chi-square difference test showed Model 2 to fit significantly better than Model 1. All fit statistics were in the acceptable range for model fit, suggesting that a model including the associations between marital distress and husband and wife psychopathology fits better than a model without these direct links. The correlations between the DAS factors and the INT and EXT factors for husbands and wives were all significant and in the expected direction (see Table 3). Wives' DAS factor was negatively related to Wives' and Husband's INT and EXT factors (AW and PH), while Husband's DAS factor was significantly negatively related to Husband's- and Wives' INT and EXT factors (AH and PW). The effects were generally moderate in magnitude and similar across gender; for instance, the AW path for INT was −.25, while the AH path for INT was −.32, and the PW path for EXT was −.25 while the PH path was −.19.

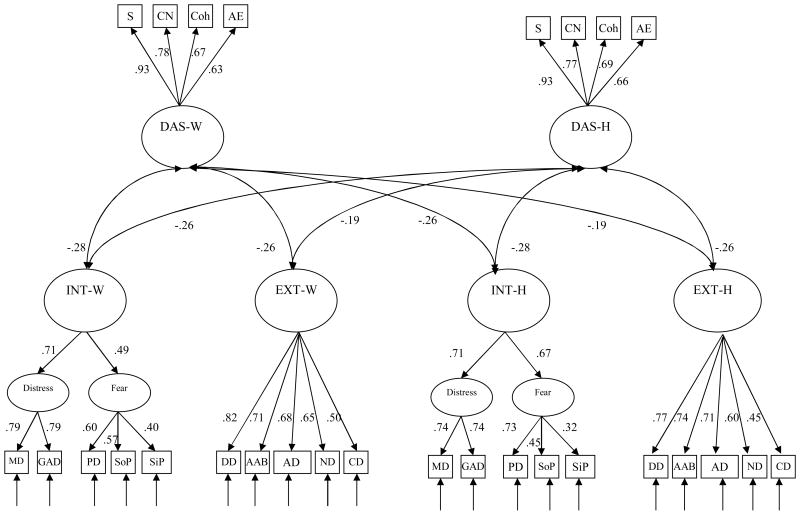

Next, we examined the similarity of these actor and partner effects across gender. The AW and AH paths for INT, AW and AH paths for EXT, PW and PH paths for INT, and PW and PH paths for EXT were constrained to be equal (see Model 3). This allowed us to statistically test whether there were gender differences in the magnitude of these effects. This constrained model provided a reasonable fit to the data, as indicated by a nonsignificant DIFFTEST result and CFI, TLI, and RMSEA values that were essentially identical to the unconstrained model (Model 2; see Table 2). Actor and partner effects were all significant and similar in magnitude to actor and partner effects from the unconstrained model (see Table 3). The strongest effect was the actor effect for INT (−.28), while the weakest effect was the partner effect for EXT (−.19). The standardized path estimates for Model 3 are shown in Figure 2. For clarity, path estimates for the correlations between INT and EXT factors and the DAS factors are not shown but are presented in Table 34.

Figure 2.

Completely standardized path diagram of the best-fitting model of associations between INT and EXT psychopathology and Marital Adjustment (DAS) (Model 3 from Table 2). For clarity, path estimates were omitted for the correlations between INT and EXT factors, the correlations between the DAS factors, and the correlated DAS residuals (but are presented in Table 3). For INT/EXT: MD=Major Depression, GAD=Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PD=Panic Disorder, SoP=Social Phobia, SiP=Simple Phobia, DD=Drug Dependence, AAB=Adult Antisocial Behavior, AD=Alcohol Dependence, ND=Nicotine Dependence, CD=Conduct Disorder. For DAS: S=Satisfaction, CN=Consensus, Coh=Cohesion, AE=Affectional Expression. All parameter estimates statistically significant (p's < .05).

Finally, to explore the generality vs. specificity of the associations between marital distress and psychopathology, we tested for any possible unique relationships between the individual clinical disorders and marital adjustment. Specifically, we fit four separate models, building on Model 3. In each, we included a covariance between the DAS factor for either husbands or wives and the observed indicators of the INT and EXT factors for husbands or wives (i.e., the actor or partner effects of DAS on the ten indicators). For instance, the DAS factor for wives was allowed to covary with the psychopathology indicators comprising the INT and EXT factors for wives, resulting in 10 covariance paths. Then, the covariances between the DAS factor for husbands and the residual variances of the 10 psychopathology variables for husbands were computed. This was repeated for the partner effects of DAS on the 10 indicators. A Bonferroni corrected alpha value of .00125 (.05/40) was used to identify significant covariances. Only one of the 40 covariances trended toward significance: wives' SiP was positively correlated with the DAS factor for wives (β=.12, p=.004), suggesting that the unique aspects of simple phobia may be associated with greater marital adjustment for wives5. In general, it appears that the associations between psychopathology variables and marital adjustment can largely be accounted for by the INT and EXT factors.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the associations between the INT and EXT spectrums and marital distress, thus allowing us to handle issues of comorbidity among clinical disorders and examine the specificity and generality of these associations. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether the strong and replicable relationships found between marital distress and various comorbid psychopathology syndromes are due to their shared vs. specific variance. Structural equation modeling was conducted to test the associations between latent INT, EXT, and marital adjustment factors for both members of a large community sample of long-term married couples. We predicted that both actor and partner measures of INT and EXT psychopathology would be significantly negatively related to latent factors of relationship adjustment. We also examined whether there were any unique associations between specific clinical disorders (after accounting for shared variance with the latent INT/EXT factors) and marital satisfaction. Results were generally consistent with our hypotheses. Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology factors were significantly negatively associated with marital adjustment in both the individual and his or her partner. After accounting for the impact of the INT and EXT factors, there were no significant independent associations with any specific forms of psychopathology. Overall, the findings from the current study largely confirmed our predictions and have important implications for future work examining the role of marital distress as an environmental stressor that may manifest as varied clinical disorders from the INT and EXT spectrums.

As expected, marital distress as measured by the DAS (total score and subscales) was significantly negatively correlated with the psychopathology indicator variables. In line with extensive research findings to date, marital satisfaction was negatively correlated with symptoms of major depression for both men and women (Uebelacker & Whisman, 2006; Whisman & Bruce, 1999; Whisman & Uebelacker, 2003; Whisman & Uebelacker, 2009). Several syndromes encompassed by the EXT spectrum were particularly likely to be significantly, negatively correlated with marital satisfaction. While there is substantial research linking marital functioning to alcohol use and related problems (Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Marshal, 2003), there is much smaller empirical evidence for the association between drug use disorders and marital distress. The significant correlations between illicit drug dependence and marital satisfaction found in the current study add to this literature.

We confirmed the INT-EXT factor structure in the data from our sample. As expected, we found that INT and EXT factors for husbands and wives were significantly and negatively related to a latent factor of marital adjustment. These findings add to the already considerable literature documenting the associations between psychopathology and marital distress. Previous work has predominantly handled comorbidity of clinical disorders by statistically covarying for these associations (e.g., Whisman, 1999). However, we conceptualized symptoms of mental illness as part of a latent factor, the manifestation of which may depend on environmental factors (e.g., life stressors; Kendler et al., 2003). The fact that INT and EXT factors were negatively related to marital satisfaction suggests that the many replicable associations between different Axis I clinical disorders and marital distress may be a function, at least in part, of a more general transaction between spectrums of psychopathology and marital adjustment. Moreover, the magnitude of the actor and partner effects between marital adjustment and the INT and EXT factors was similar across gender. Often, there is a bias to interpret the associations between types of mental disorders and marital adjustment along gender-specific lines; for instance, marital interventions for substance use treatment are more common among male patients (e.g., Fals-Stewart, O'Farrell, Birchler, Cordova, & Kelley, 2005) while participants in marital interventions for depression are predominantly female (e.g., Bodenmann, et al., 2008). Our findings lead us to conclude that INT and EXT psychopathology should be assessed in both members of a couple presenting with relationship difficulties. Husbands and wives may differ in mean-level of symptoms of internalizing and externalizing spectrums, but the impact on marital distress is equally important for both members of the couple.

Our findings support the hypothesis that marital distress may indeed be a function of the general inability to regulate emotions that is at the heart of internalizing psychopathology or the tendency to project distress outward that defines the externalizing spectrum. A related aim of the current study was to determine if marital adjustment may also be related to the specific pattern of behavior that results from a particular clinical syndrome. We analyzed whether there were any specific associations between forms of psychopathology and marital distress, finding that the residual variances of the symptom count variables were almost completely unrelated to marital functioning after accounting for the variance shared with the higher-order spectrums. The results of these analyses are intuitively appealing, suggesting that it is the temperamental core (e.g., Clark, 2005) at the heart of the internalizing and externalizing spectrums which lead to not only symptoms of mental illness but the behaviors and cognitions which negatively impact marital quality. Certainly, though, it will be incumbent on future studies to examine whether the same pattern of results replicates in other samples and with other measures. In the current study, we utilized a latent factor of overall relationship adjustment as measured by self-report. Findings may be different depending on the type of relationship functioning measure (e.g., communication, acceptance) and how it is collected (e.g., observation, partner-report).

This is the first time (to our knowledge) that the INT-EXT framework has been used to understand the associations between comorbid psychopathology and marital adjustment in an adult sample. The use of the INT-EXT spectrums to conceptualize the structure and comorbidity of common mental disorders is now well-accepted (Andrews, et al., 2009; Kendler, et al., 2003; Krueger, 1999; Krueger & Markon, 2006; Vollebergh, et al., 2001). One important question as research goes forward will be to distinguish between disorders subsumed under each dimension, and how different risk factors are related to manifestation of the spectrums as specific types of disorders. Marital distress may be an environmental risk factor which triggers internalizing psychopathology per se (e.g., South & Krueger, 2008), while marital status may be a protective factor for alcohol problems (Curran, Muthen, & Harford, 1998; Miller-Tutzauer, Leonard, & Windle, 1991). Future research should focus on understanding the mechanisms involved in the link between INT/EXT psychopathology, behavior exchanged between spouses, and ultimate evaluations of relationship functioning.

This study does have several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, this was a cross-sectional study that utilized lifetime measures of psychopathology and self-reports of past-year marital distress; as such, we were unable to posit directional effects (i.e., from distress to psychopathology vs. from psychopathology to distress). A conflicted or unsatisfying marriage may act as an environmental stressor leading to the development or exacerbation of psychopathology in vulnerable individuals (Beach, et al., 2003; Overbeek, et al., 2006; Whisman, 2007; Whisman & Bruce, 1999; Whisman, et al., 2006a). Alternatively, marital distress may result from the presence of psychopathology in one or both spouses (Coyne, 1976; Hammen, 1991; Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, & Cartwright, 2009; Whisman, et al., 2004). A reasonable synthetic perspective, which also has empirical support, proposes a bidirectional relationship between distress and psychopathology over time (Choi & Marks, 2008; Davila, Karney, Hall, & Bradbury, 2003; Kouros, Papp, & Cummings, 2008). These differing views are not necessarily incompatible; in fact, the bidirectional relationship between psychopathology and marital distress that has received empirical support (Davila, et al., 2003) may be attributable to how this temperamental core is manifested. Future research would do well to examine the relationship between marital satisfaction and the INT and EXT spectrums over time.

Another limitation of the current study was the use of a sample of predominantly Caucasian, married couples who had been together a relatively long time (at least long enough to have an 11 year old child); different results may have been obtained if we used a sample of established couples without children, newlywed couples, dating couples, or couples of different races/ethnicities. We also utilized a questionnaire measure of marital satisfaction. While it is the most widely used measure of marital satisfaction and has been well-validated, particularly in this sample (South, et al., 2009), future research would benefit from spouse-report measures, measures of conflict, and behavioral measures of marital interaction. Also of note, the fact that the current sample was, on average, less distressed than previous community samples of married couples may have impacted our results. Further, the rates of GAD (.5% of males, 1.1% of females) in the current sample are lower than those reported in other epidemiological surveys. For instance, 12-month and lifetime prevalence estimates of GAD in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication were 3.1 and 5.7, respectively (Kessler, et al., 2005a; Kessler, et al., 2005b). Thus, our findings with regard to GAD should be considered tentative and may not replicate in future studies with samples that have higher rates of GAD. Finally, we should note that because we utilized symptom count variables as indicators of the psychopathology latent factors, the estimates of the covariances with the specific psychopathology variables were not as fully corrected for unreliability as are the covariances with the internalizing and externalizing factors. Future research that utilizes individual symptoms as indicator variables may result in a more fine grained analysis of the specific connections between marital satisfaction and different psychopathology syndromes.

In sum, this study extends the work examining psychopathology and marital distress. Our findings have broader implications not only for the mechanisms by which psychopathology influences marital functioning, but also for therapeutic interventions. Couples may well benefit from dual therapy that includes treatment for congruent mental illness and poor relationship functioning. These interventions should be targeted at the mechanisms by which broad classes of psychopathology impair communication and interaction and thus leads to dysfunction in the marital relationship. In this way, prevention and intervention efforts can focus on the ways in which long-standing patterns of personality, cognition, and behavior can trigger both symptoms of mental illness and dysfunction in close, interpersonal relationships. Our findings suggest that intervention efforts which focus on shared processes linking specific varieties of psychopathology may be most effective in ameliorating associated relationship distress.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Grants DA05147, AA09367, and DA13240. The authors wish to thank Jaime Derringer for her assistance with this article.

Footnotes

Of the 929 couples, data on the four marital satisfaction indicator variables was missing for 9 to 14% of wives and 19 to 24% of husbands, and data on the 10 symptom count variables was missing on 1 to 2% of wives and 4 to 6% of husbands.

We could have chosen to cut GAD at several points, but a cut point of above 5 symptoms led to approximately 1% meeting this threshold in both husbands and wives.

An alternative identifying constraint was also examined, in which the loadings of both lower-order factors of Distress and Fear were set equal to each other. A series of models with this identifying constraint were similar to the final results presented here, in both overall model fit statistics and parameter estimates. Full results are available from the first author.

Lifetime symptoms of psychopathology are likely to be a strong reflection of core clinical constructs that negatively impact interpersonal relationships, particularly the marital relationship. For instance, the temperamental core at the heart of the EXT construct that accounts for conduct disordered behavior in adolescence and antisocial and substance-using behavior in adulthood can reasonably be expected to also play a role in behaviors that lead to negative marital adjustment in adulthood. However, to determine if our results were somehow dependent on the use of lifetime symptoms, we also carried out an analysis making use of the symptom picture in the past 12 months. Using a combination of symptom offset and recency variables, it was possible to create new indictor variables that were coded 0 = no symptoms present in the last 12 months and 1= symptoms present in the last 12 months. The three models presented in Table 2 were re-run with these new pathology indicator variables. The model had to be modified somewhat to converge, such that the five internalizing variables were modeled as indicators of one factor. As with the models presented in Table 2, the best-fitting model was Model 3 with constrained Actor and Partner effects. Importantly, the Actor and Partner effects were all significant, in the expected direction, and similar in magnitude to the effects found when only lifetime symptom count variables were utilized. These findings bolster our interpretation that marital distress is a function of the current impairment that results from either INT or EXT psychopathology. See supplementary online material.

We attempted to fit a model with all 40 paths (i.e., all covariances between the indicator psychopathology variables and the latent DAS factors), in a method analogous to a protected t-test; however, this model did not converge. A model that includes 36 of the 40 paths (all except DASwives with GADhusbands, DAShusbands with GADhusbands, DASwives with DDhusbands and DAShusbands with DDhusbands) did converge; results of the DIFFTEST indicated that Model 3 (the more restrictive model without the covariances) worsened the fit of the model (40.28, p=.02). Only two of the 36 covariances were significant: DASwives and NDhusbands (p=.008) and DAShusbands with AABwives (p=.021). The fact that this method also found that a majority of the covariances were nonsigificant bolstered our conclusion that the majority of the link between marital satisfaction and psychopathology is at the higher-order spectrum level.

The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn

Contributor Information

Susan C. South, Purdue University

Robert F. Krueger, University of Minnesota—Twin Cities

William G. Iacono, University of Minnesota—Twin Cities

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd Edition, Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Goldberg DP, Krueger RF, Carpenter WTJ, Hyman SE, Sachdev P, et al. Exploring the feasability of a meta-structure for DSM-V and ICD-11: Could it improve utility and validity? Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:1993–2000. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Katz J, Kim S, Brody G. Prospective effects of marital satisfaction on depressive symptoms in established marriages: A dyadic model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003;20:355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Plancherel B, Beach SRH, Widmer K, Gabriel B, Meuwly N, et al. Effects of coping-oriented couples therapy on depression: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:944–954. doi: 10.1037/a0013467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth P, Rodgers B. Concordance in the mental health of spouses: Analysis of a large national household panel survey. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2006;36:685–697. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Marks NF. Marital conflict, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2008;70:377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Muthen BO, Harford TC. The influence of changes in marital status on developmental trajectories of alcohol use in young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:647–658. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Hall TW, Bradbury TN. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: Within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:557–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan-Sewell RT, Krueger RF, Shea MT. Co-occurrence with syndrome disorders. In: Livesley WJ, editor. Handbook of Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. New York: Guilford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, O'Farrell TJ. Drug-abusing patients and their intimate partners: Dyadic adjustment, relationship stability, and substance use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:11–23. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Birchler GR, Cordova J, Kelley ML. Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse: Where we've been, where we are, and where we're going. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;19:229–246. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Galbaud du Fort G, Boothroyd LJ, Bland RC, Newman SC, Kakuma R. Spouse similarity for antisocial behaviour in the general population. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research in Psychiatry and the Allied Sciences. 2002;32:1407–1416. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, et al. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1125–1136. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen CL. The generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, Prescott C, Kendler KS. A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:857–864. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Sayers SL, Bellack AS. Global marital satisfaction versus marital adjustment: An empirical comparison of three measures. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. 2007 doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Illicit drug use and marital satisfaction. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Humbad MN, Donnellan MB, Iacono WG, Burt SA. Externalizing psychopathology and marital adjustment in long-term marriages: Results from a large combined sample of married couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:151–162. doi: 10.1037/a0017981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Developmental Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Follette WC, Revenstorf D, Baucom DH, Hahlweg K, Margolin G. Variability in outcome and clinical significance of behavioral marital therapy: A reanalysis of outcome data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:497–504. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Models of non-independence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13:279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes MA, Malone SM, Elkins IJ, Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. The Enrichment Study of the Minnesota Twin Family Study: Increasing the yield of twin families at high risk for externalizing psychopathology. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12:489–501. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros CD, Papp LM, Cummings EM. Interrelations and moderators of longitudinal links between marital satisfaction and depressive symptoms among couples in established relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:667–677. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.5.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon K. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. 2007 doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, Waldman ID, Israel AC. A critical examination of the use of the term “comorbidity” in psychopathology research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1994;1:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Low N, Cui L, Merikangas KR. Spousal concordance for substance use and anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41:942–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE. Modeling psychopathology structure: A symptom-level analysis of Axis I and Axis II disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:273–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF. Categorical and Continuous Models of Liability to Externalizing Disorders: A Direct Comparison in NESARC. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1352–1359. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Lish JD, Klerman GL. Quality of life in panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:984–992. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or worse? The effect of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD. Anxiety disorders and marital quality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:767–776. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Tutzauer C, Leonard KE, Windle M. Marriage and alcohol use: A longitudinal study of “Maturing out”. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:434–440. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Fifth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD. Drug use and intimate relationships among women and men: Separating specific from general effects in prospective data using structural equation models. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:463–476. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek G, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, Scholte R, de Kemp R, Engels R. Longitudinal associations of marital quality and marital dissolution with the incidence of DSM-III-R disorders. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:284–291. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau JM, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Griffith JW, Epstein AM. Testing a hierarchical model of anxiety and depression in adolescents: A tri-level model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24:334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R, Wilson-Genderson M, Cartwright FP. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction in the context of chronic disease: A longitudinal dyadic analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:573–584. doi: 10.1037/a0015878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LM, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, et al. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snjiders TA, Kenny DA. The social relations model for family data: A multilevel approach. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:471–486. [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Krueger RF. Marital quality moderates genetic and environmental influences on the internalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:826–837. doi: 10.1037/a0013499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Factorial invariance of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale across gender. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:622–628. doi: 10.1037/a0017572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Turkheimer E, Oltmanns TF. Personality disorder symptoms and marital functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:769–780. doi: 10.1037/a0013346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Whisman MA. Moderators of the association between marital dissatisfaction and depression in a national population-based sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:40–46. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WAM, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Marital dissatisfaction and psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:701–706. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Marital distress and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in a population-based national survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:638–643. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Bruce ML. Marital distress and incidence of major depressive episode in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:674–678. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Schonbrun YC. Social consequences of borderline personality disorder symptoms in a population-based survey: Marital distress, marital violence, and marital disruption. 2009 doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]