Abstract

We discuss the functional roles of β2-adrenergic receptors in skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy as well as the adaptive responses of β2-adrenergic receptor expression to anabolic and catabolic conditions. β2-Adrenergic receptor stimulation using anabolic drugs increases muscle mass by promoting muscle protein synthesis and/or attenuating protein degradation. These effects are prevented by the downregulation of the receptor. Endurance training improves oxidative performance partly by increasing β2-adrenergic receptor density in exercise-recruited slow-twitch muscles. However, excessive stimulation of β2-adrenergic receptors negates their beneficial effects. Although the preventive effects of β2-adrenergic receptor stimulation on atrophy induced by muscle disuse and catabolic hormones or drugs are observed, these catabolic conditions decrease β2-adrenergic receptor expression in slow-twitch muscles. These findings present evidence against the use of β2-adrenergic agonists in therapy for muscle wasting and weakness. Thus, β2-adrenergic receptors in the skeletal muscles play an important physiological role in the regulation of protein and energy balance.

1. Introduction

The skeletal muscle is the most abundant tissue in the human body comprising 40–50% of body mass. Skeletal muscle protein undergoes rapid turnover, which is regulated by the balance between the rates of protein synthesis and degradation. Physical activity (exercise training) and anabolic hormones and drugs (sports doping) increase muscle protein content. However, sarcopenia and muscle disuse (due to unloading, microgravity, or inactivity) and diseases decrease muscle protein content. The rate of protein synthesis is at least in part mediated by β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs) in skeletal muscles in both anabolic and catabolic conditions.

ARs belong to the guanine nucleotide-binding G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. Skeletal muscle contains a significant proportion of β-ARs. The β2 subtype is the most abundant, while ~7–10% of ARs are the β1 subtype [1, 2]. Furthermore, β2-AR is more dense in slow-twitch muscles than in fast-twitch muscles [3, 4]. However, the magnitude of anabolic responses to β2-adrenergic agonists is greater in fast-twitch muscles than in slow-twitch muscles [5–8].

The family of β-ARs was originally believed to signal predominantly via coupling with a stimulatory guanine nucleotide-binding protein, Gαs; however, recent studies revealed that both β2- and β3-ARs in skeletal muscle are also capable of coupling to an inhibitory guanine nucleotide-binding protein, Gαi [9]. β2-AR activates the Gαs/adenylyl cyclase (AC)/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway. The signaling pathway is at least in part responsible for the anabolic response of skeletal muscle to β2-AR stimulation. Further, in addition to the well-documented inhibition of AC activity [10], β2-AR coupling to Gαi activates Gαs-independent pathways [11].

β 2-AR has 7 transmembrane α helices forming 3 extracellular loops, including an NH2 terminus and 3 intracellular loops that include a COOH terminus [12]. β2-AR contains phosphorylation sites in the third intracellular loop and proximal cytoplasmic tail. Phosphorylation of these sites triggers the agonist-promoted desensitization, internalization, and degradation of the receptor [13]. These regulatory mechanisms contribute to maintaining agonist-induced β2-AR responsiveness in various conditions.

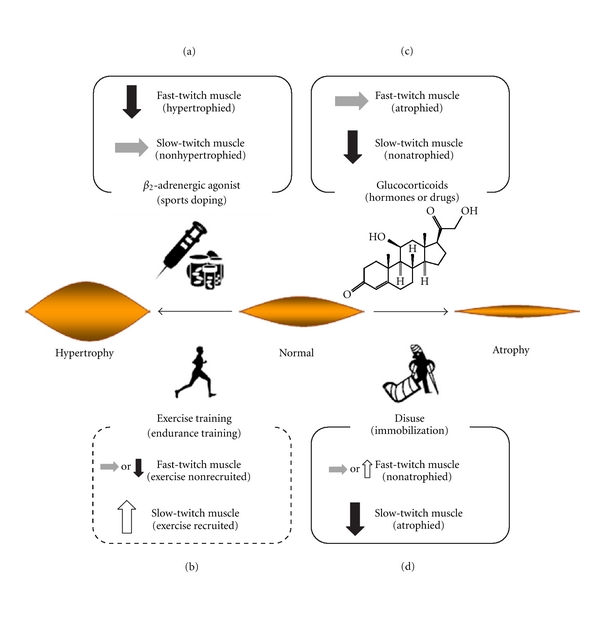

The adaptive responses of β2-AR expression to anabolic and catabolic conditions in skeletal muscles are shown in Figure 1. Understanding the correlation between changes in muscle mass and β2-AR expression in several anabolic or catabolic conditions present scientific evidence to eradicate sports doping and identify novel approaches for attenuating muscle atrophy concomitant with disuse and various diseases. This paper will discuss the effects of (1) pharmacological β2-AR stimulation (sports doping), (2) muscle hypertrophy (exercise training), and (3) muscle atrophy (catabolic conditions and hormones) on β2-AR expression in skeletal muscles.

Figure 1.

Changes in β2-AR expression in hypertrophied and atrophied skeletal muscles. (a) β2-AR stimulation using anabolic drugs downregulates β2-AR expression in hypertrophied fast-twitch muscles but not in slow-twitch muscles [4, 7, 8, 14–17]. (b) Exercise training such as endurance training upregulates β2-AR expression in exercise-recruited slow-twitch muscles, whereas no changes or downregulations are observed in fast-twitch muscles [18, 19], although muscle mass is not altered. However, although exercise training such as isometric strength training induces muscle hypertrophy, there is no insight regarding the effects of such exercise on β2-AR expression. The differential effects of types of exercise training on physiological responses such as β2-AR expression and muscle hypertrophy should be clarified in more detailed and are currently being investigated by our group. (c) Catabolic hormones or drugs such as glucocorticoids downregulate β2-AR expression in nonatrophied slow-twitch muscles but not fast-twitch muscles [16, 20, 21]. (d) Muscle disuse downregulates β2-AR expression in atrophied slow-twitch muscle, whereas no changes or upregulation of receptor expression are observed in fast-twitch muscles [14, 22]. Up arrow (open arrow): upregulation of β2-AR expression; down arrow (filled arrow): downregulation of β2-AR expression; lateral arrow (shade arrow): no change.

2. Pharmacological Stimulation of β2-AR

2.1. Muscle Hypertrophy and β2-AR

A β2-adrenergic agonist, clenbuterol [1-(4-amino-3,5-dichlorobenzyl)-2-(tert-butylamino) ethanol], is used as a nonsteroidal anabolic drug for sports doping. According to the recent World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) documents, clenbuterol was the seventh most commonly used anabolic agent in 2009 (67 cases; 2.0% of all anabolic agents used).

Numerous studies have shown that the administration of β2-adrenergic agonists induces muscle hypertrophy in many species [23–25]. Experiments using mice lacking β1-AR, β2-AR, or both demonstrate that β2-adrenergic agonist-induced functions such as muscle hypertrophy are mediated by β2-AR [26]. β2-Adrenergic agonists promote muscle growth by increasing the rate of protein synthesis and/or decreasing protein degradation [23–25]. Furthermore, β2-adrenergic agonists induce slow-to-fast [myosin heavy chain (MHC)I/β → MHCIIa → MHCIId/x → MHCIIb] transformation of muscle fibers.

The β2-AR signaling pathway involves the agonist-dependent activation of Gαs, which in turn activates AC, resulting in increased cAMP production. Cyclic AMP-activated PKA initiates the transcription of many target genes via the phosphorylation of cAMP-response-element-(CRE-) binding protein (CREB) or adaptor proteins such as CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300, subsequently promoting protein synthesis [23]. While β2-AR-mediated signaling was traditionally believed to involve selective coupling to Gαs, recent studies revealed that β2-AR exhibits dual coupling to both Gαs and Gαi in skeletal muscles [9, 23]. In addition to Gαs, Gαi-linked Gβγ subunits play an active role in various cell signaling processes such as the phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3 K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/p70S6 K and PI3 K/Akt/forkhead box-O (FOXO) pathways. These signaling pathways play important roles in β2-adrenergic agonist-induced hypertrophy in skeletal muscles [23].

In addition to promoting protein synthesis, the hypertrophic response of skeletal muscles following β2-adrenergic agonist administration is associated with decreased protein degradation. β2-Adrenergic agonists attenuate protein degradation predominantly via Ca2+-dependent proteolysis and the ATP/ubiquitin-dependent pathway [27–31]. However, there is little knowledge regarding the preventive effects of β2-adrenergic agonists on the proteolysis system compared with the protein synthesis system.

The hypertrophic responses to β2-adrenergic agonists are observed much frequently in fast-twitch muscle than in slow-twitch muscle. Our group previously demonstrated that clenbuterol administration (1.0 mg·kg−1·day−1) to rats for 10 days increases the mass of fast-twitch (extensor digitorum longus: EDL) muscle without altering in slow-twitch (soleus) muscle [7, 8]; other groups also observed the same tendency [5, 6, 32–35]. However, the mechanisms of the fiber-type-dependent effects of β2-adrenergic agonists on muscle hypertrophy remain unclear.

Pearen et al. [36, 37] and Kawasaki et al. [38] identified that β2-AR activation increases the expression of the orphan nuclear receptor, NOR-1 (NR4A3), a negative regulatory factor of myostatin (a member of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily and a potent negative regulator of muscle mass), in fast-twitch muscles without altering that in slow-twitch muscles. Furthermore, Shi et al. [32] demonstrate the possibility that β2-adrenergic agonist-induced fiber-type-dependent hypertrophy is in part due to the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Moreover, the pharmacological inhibition of the PI3 K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway revealed that the attenuation of the anabolic response to clenbuterol is greater in fast-twitch muscles than in slow-twitch muscles [30]. In addition to the protein synthesis system, Yimlamai et al. [35] found that clenbuterol inhibits ubiquitination more strongly in fast-twitch muscles than in slow-twitch muscles. Thus, β2-AR-mediated signaling pathways tend to promote muscle hypertrophy to a greater extent in fast-twitch muscle than in slow-twitch muscle.

2.2. Posttranslational Regulation of β2-AR

As shown in Table 1, some reports focus on the responses of β2-AR expression to β2-AR stimulation in skeletal muscles [4, 7, 8, 14–17]. This is because β2-AR functions such as muscle hypertrophy are maintained via receptor density, including synthesis and downregulation as well as receptor sensitivity, which includes receptor sensitization, desensitization, phosphorylation, and internalization [13, 39, 40].

Table 1.

Responses of β2-AR expression in skeletal muscle to anabolic and catabolic conditions.

| Conditions | Species | β2-AR | Other findings | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | mRNA | ||||

| β2-AR stimulation | |||||

| Fenoterol | Rat | ↓ (FT) | n.d. | [4] | |

| (1.4 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 4 weeks) | →(ST) | ||||

| Clenbuterol | Rat | n.d. | ↓ (FT) | β1-AR mRNA ↓ (LV) | [7] |

| (1.0 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 10 days) | → (ST) | β2-AR mRNA ↓ (LV) | |||

| Clenbuterol | Rat | n.d. | ↓ (FT) | GR mRNA ↓ (FT) | [8] |

| (1.0 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 10 days) | → (ST) | HuR mRNA ↓ (FT) | |||

| AUF1 mRNA ↓ (FT) | |||||

| hnRNP A1 mRNA ↓ (FT) | |||||

| Fenoterol | Rat | → (FT, ST) | ↓ (FT, ST) | Gαs content→(FT, ST) | [14] |

| (1.4 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 2–7 days) | AC activity→ (FT, ST) | ||||

| Clenbuterol | Rat | ↓ (FT+ST) | n.d. | [15] | |

| (2.0 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 18 days) | |||||

| Clenbuterol | Rat | ↓ (FT) | n.d. | β2-AR affinity→ (FT) | [16] |

| (4.0 mg · kg−1 of feed, 10 days) | |||||

| Clenbuterol | Rat | ↓ (FT+ST) | n.d. | [17] | |

| (0.2 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 7 days) | |||||

| Clenbuterol (50 μM) | Mouse (ex vivo) | Phosphorylated | n.d. | cAMP concentration ↑ | [41] |

| Formoterol (100 μM) | β2-AR ↑ (ST), | (FT, ST) | |||

| Salbutamol (500 μM) | →(FT) | ||||

| Endurance training | |||||

| Treadmill (12 weeks) | Rat | ↓ (FT) | n.d. | β2-AR afflnity → | [18] |

| AC activty ↓ | |||||

| Gαs content ↓ | |||||

| Treadmill (18 weeks) | Rat | → (FT) | n.d. | AC activity ↑ (FT, ST) | [19] |

| ↑ (ST) | β2-AR density→(acute) | ||||

| Catabolic conditions | |||||

| Dexamethasone | Rat | → (FT, ST) | → (FT) | GR mRNA ↓ (FT, ST) | [20] |

| (1.0 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 10 days) | ↓ (ST) | CREB mRNA ↓ (ST) | |||

| AUF1 mRNA ↑(FT) | |||||

| Dexamethasone | Rat | n.d. | → (FT) | GR mRNA ↓ (FT, ST) | [21] |

| (1.0 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 10 days) | ↓ (ST) | β1-AR mRNA ↑ (LV) | |||

| Dexamethasone | Rat | → (FT) | n.d. | β2-AR affinity→(FT) | [16] |

| (0.2 mg · kg−1 · day−1, 10 days) | |||||

| Casted-immobilization | Rat | → (FT, ST) | → (FT) | GR mRNA ↓ (ST) | [22] |

| (10 days) | ↓ (ST) | GR protein ↓ (ST) | |||

| Aging | Rat | → (FT, ST) | n.d. | [4] | |

| Injury | Rat | ↑ (FT) | ↑ (FT) | Gαs content ↑ (FT), ↓ (ST) | [14] |

| (bupivacaine injection) | ↓ (ST) | ↓ (ST) | AC activity ↑ (FT, ST) | ||

FT, fast-twitch muscle; ST, slow-twitch muscle; LV, left ventricle muscle. Up arrow, increase; down arrow, decrease; lateral arrow, no change. n.d., no data.

The desensitization of β2-AR is associated with receptor phosphorylation. McCormick et al. [41] demonstrate that fast-twitch fibers mainly express nonphosphorylated β2-AR, whereas slow-twitch fibers predominantly express phosphorylated β2-AR. Furthermore, treating muscle fibers with β2-adrenergic agonists (e.g., clenbuterol, formoterol, and salbutamol) increases the phosphorylation of β2-AR in slow-twitch fibers but not in fast-twitch fibers [41]. On the other hand, the receptor phosphorylation occurs via the actions of protein kinases (such as PKA) and/or GPCR kinase (GRK). Rat skeletal muscles contain predominantly GRK2 and GRK5; GRK protein is expressed more in fast-twitch muscles than in slow-twitch muscles. These expression levels in each type of muscle fiber are not altered by β2-adrenergic agonist administration [42]. Thus, there is a negative correlation between the level of phosphorylated β2-AR and receptor kinase. Therefore, further investigation is needed to reveal the detailed mechanism of β2-AR phosphorylation.

Following β2-AR phosphorylation, the receptor is internalized into the cytosol. The internalized β2-AR is then degraded or dephosphorylated and subsequently recycled to the membrane [13, 43–45]. Prolonged administration of β2-adrenergic agonists leads to the downregulation of β2-AR density in skeletal muscles [15–17]. These posttranslational regulations are advantageous for maintaining the rate of muscle protein synthesis and/or degradation.

2.3. Short-Term and Chronic Transcriptional Regulation of β2-AR

β 2-AR synthesis, including transcription and subsequent translation, is required to restore transmembrane receptor density. The process of β2-AR synthesis can be separated into 2 pathways: (1) the positive autoregulation of β2-AR gene transcription via receptor-mediated elevation of cAMP concentration followed by the phosphorylation and activation of CREB [46, 47] and (2) the transactivation of the β2-AR gene via interaction between hormones and the nuclear receptor complex and response elements on the β2-AR promoter region [48]. In particular, the transcription of the β2-AR gene and the subsequent mRNA expression via cAMP-mediated CRE activation increased in response to short-term β2-adrenergic agonist exposure [46, 47]. Moreover, treatment with glucocorticoids or thyroid hormone transactivates the β2-AR gene both in vitro and in vivo [48–51].

Our previous reports demonstrate that clenbuterol administration (1.0 mg·kg−1·day−1) for 10 days to rats decreases β2-AR mRNA expression in the fast-twitch EDL muscle without altering that in the slow-twitch soleus muscle [7, 8]. Furthermore, the mRNA expression of glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) was also decreased with clenbuterol treatment in the EDL muscle but not in the soleus muscle [8]. Glucocorticoids and the GR complex activate the transcription of the β2-AR gene via interaction with glucocorticoid response elements (GREs), consensus cis-acting DNA sequences (i.e., AGA ACA nnn TGT TCT) on its promoter regions [48], thus upregulating β2-AR expression [16, 50, 51]. These findings corroborate our results that there is a positive correlation between the expression levels of β2-AR and GR in skeletal muscles. Beitzel et al. [14] also report that administrating the β-adrenergic agonist, fenoterol (1.4 mg·kg−1·day−1, i.p.), for 5 days decreases β2-AR mRNA expression in the EDL and soleus muscles. Thus, in contrast to the transactivation of the β2-AR gene and increase in the mRNA level in response to short-term agonist exposure, chronic β2-adrenergic stimulation inhibits β2-AR synthesis in skeletal muscles.

2.4. Posttranscriptional Regulation of β2-AR

In addition to post-translational and transcriptional regulation, several groups focus on the posttranscriptional regulation of β2-AR mRNA. β2-AR mRNA contains an AU-rich element (ARE) within the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) that can be recognized by several mRNA-binding proteins, including Hu antigen R (HuR), AU-rich element binding/degradation factor1 (AUF1), and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNP A1) [52–55]. These factors play a role in the regulation of β2-AR mRNA stability [52–55]. Our study demonstrates that clenbuterol-induced stimulation of β2-AR decreases the mRNA expressions of these factors in the EDL but not in the soleus muscle [8], suggesting that the posttranscriptional process of β2-AR synthesis requires the stability of its mRNA to be regulated.

3. Exercise Training and β2-AR

Strength-resistance training increases muscle mass [56], fiber cross-sectional area [57], protein and RNA contents [58], and the capacity to generate force [59]. In contrast to strength training, endurance training is characterized by increased mitochondrial mass [60], increased oxidative enzymes [61], decreased glycolytic enzymes [62], increased slow contractile and regulatory proteins [62], and decreased fast fiber area [63]. These findings suggest that the functional roles of β2-AR in skeletal muscles differ with the type of exercise training.

3.1. Strength Exercise Training and β2-AR

Mounier et al. [64] investigated the changes in the weight of the EDL muscle induced by clenbuterol administration, strength training, and a combination of both. They found that the effects of strength training and clenbuterol on muscle hypertrophy were not additive in fast-twitch muscles. Their report also demonstrates that the strength-training-induced enhancement of lactate dehydrogenase-specific activity is completely inhibited by clenbuterol administration, while the clenbuterol-induced decrease in monocarboxylate transporter1 mRNA expression is completely offset by strength training [64]. Thus, there are no synergetic effects of a combination of strength training and β2-AR stimulation on muscle mass. Furthermore, strength training counteracts molecular modifications such as glycolytic control induced by chronic clenbuterol administration in fast-twitch muscles to some extent. However, our evidence regarding the synergistic effects of strength training and β2-AR stimulation is insufficient because the experimental models of strength-trained animals are not fully established.

3.2. Endurance Exercise Training and β2-AR

In contrast to strength training, β2-AR stimulation affects endurance-training-induced modulations such as contractile activity [65], muscle fiber-type shift [65], metabolic enzyme activity [66], and insulin resistance [67, 68]. Lynch et al. [65] demonstrated that low-intensity endurance training prevents clenbuterol-induced slow-to-fast (type I fiber → type II fiber) fiber-type transformation in the EDL and soleus muscles, and thereby offsets the clenbuterol-induced decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity in fast-twitch fibers. These results suggest that endurance-training-heightened muscle aerobic capacity is attenuated by β2-AR stimulation-induced muscle fiber-type transformations. Furthermore, pharmacological β-AR blockage diminishes the endurance-training-induced increase in citrate synthase activity in the fast-twitch plantaris muscle [66]. Moreover, clenbuterol administration prevents the endurance-training-induced improvement in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and attenuates the increase in citrate synthase activity in the skeletal muscles of obese Zucker rats [67, 68]. These findings demonstrate that the endurance-training-induced increase in aerobic metabolism in skeletal muscles requires moderate but not excessive stimulation of β2-AR.

Recently, Miura et al. [69] demonstrated that an increase in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) mRNA in response to exercise is mediated by β2-AR activation. Furthermore, the Ca2+-signaling [70] and p38 MAPK pathways [71], which is downstream of β2-AR, are activated in skeletal muscles in response to exercise, which regulates PGC-1α expression. Since PGC-1α promotes mitochondrial biogenesis [72], the exercise-induced activation of β2-AR may in part enhance aerobic capacity by increasing PGC-1α expression. Thus, β2-AR stimulation is essential for enhancing the effects of exercise training on muscle functions such as fiber-type shift as well as oxidative and anaerobic metabolism.

3.3. Response of β2-AR Expression to Exercise Training

As mentioned above, the functional roles of β2-AR during exercise training are physiologically important in skeletal muscles. Therefore, changes in the expression and sensitivity of β2-AR should be important for the metabolic, anabolic, and catabolic adaptations of skeletal muscles during exercise training. Nevertheless, there is little information on the response of β2-AR expression to exercise training in skeletal muscles. However, many studies demonstrate the effects of exercise training on β2-AR expression in several tissues and cell types such as myocardia [73, 74], adipocytes [75], and macrophages [76]. Barbier et al. [73] demonstrated that exercise training induces changes in the distribution of β1-, β2-, and β3-AR densities in the rat left ventricle. In adipocytes, the exercise-induced trafficking of β2-AR into the cell membrane from the cytosol is coupled with adipocytes' function to increase intracellular cAMP production [75]. Kizaki et al. [76] also found a reduction in the expression of β2-AR mRNA in macrophages and highlight the significance of β2-AR in the exercise training-induced improvement of macrophages' innate immune function. Thus, changes in β2-AR expression play a role in physiological adaptations to exercise training in several tissues.

A few studies also report the effects of exercise training on β-AR in skeletal muscles [18, 19, 77, 78] (Table 1). Nieto et al. [18] demonstrate that β-AR density and Gαs content in the fast-twitch gastrocnemius muscle are significantly lower in endurance-exercised rats than in controls. They also reveal that exercise reduces receptor- and nonreceptor-mediated (i.e., pharmacological stimulation of AC by forskolin) AC activity in muscles [18]. However, Buckenmeyer et al. [19] report that endurance training increases β-AR density in slow-twitch muscles that are primarily recruited during endurance training, whereas β-AR density is not altered in fast-twitch muscles. Their report also demonstrates that receptor-mediated AC activity in slow-twitch muscles is increased by endurance training, and nonreceptor-mediated AC activity is increased by training in both fast- and slow-twitch muscles [19]. In contrast to chronic endurance training, the effects of acute exercise on β-AR density and AC activity in each type of muscle were not observed [19]. Therefore, endurance-exercise-training-induced changes in β2-AR expression and signaling in slow-twitch muscle contributes to the adaptation of metabolic and anabolic capacities during exercise.

4. Muscle Atrophy and β2-AR

4.1. Preventive Roles of β2-AR in Disuse-Induced Muscle Atrophy

Muscle wasting and weakness are common in physiological and pathological conditions, including aging, cancer cachexia, sepsis, other forms of catabolic stress, denervation, disuse (e.g., unloading, inactivity, and microgravity), burns, human immunodeficiency virus-(HIV)-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), chronic kidney or heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and muscular dystrophies. For many of these conditions, the anabolic properties of β2-adrenergic agonists provide therapeutic potential for attenuating or reversing muscle wasting, muscle fiber atrophy, and muscle weakness. These β2-adrenergic agonists also have important clinical significance for enhancing muscle repair and restoring muscle function after muscle atrophy.

In particular, muscle disuse, which is mainly reflected by increased myofibrillar protein breakdown, causes a progressive decrease in muscle strength associated with a decreased cross-sectional area of muscle fibers. Therefore, preventing disuse-induced muscle atrophy is a problem requiring urgent attention and highlights β2-AR as a target of pharmacological stimulation. Since 2000, many groups have focused on the preventive effects of β2-adrenergic agonist on disuse-induced muscle atrophy [4, 34, 35, 79].

Yimlamai et al. [35] demonstrate that clenbuterol attenuates the hindlimb unweighting-induced atrophy and reduces ubiquitin conjugates only in fast-twitch plantaris and tibialis anterior muscles but not in the slow-twitch soleus muscle; this suggests that clenbuterol alleviates hindlimb unweighting-induced atrophy, particularly, in fast-twitch muscles at least in part through a muscle-specific inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. However, Stevens et al. [34] report that clenbuterol treatment accelerates hindlimb unweighting-induced slow-to-fast (MHCI/β → MHCIIa → MHCIId/x → MHCIIb) transformation in the soleus muscle.β2-Adrenergic agonist also reverses muscle wasting and weakness in several conditions such as aging [4], muscular dystrophy [29], denervation [80], cancer cachexia [28], and myotoxic injury [81].

4.2. Preventive Roles of β2-AR in Catabolic Hormone-Induced Muscle Atrophy

Prolonged muscle disuse and/or unloading increases the secretion of glucocorticoids, which promotes the catabolism of muscle proteins via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [82, 83]. Sepsis also elevates plasma glucocorticoids and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels [84]. Therefore, several studies focus on the counteractive effects of β2-AR stimulation on glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy [16, 85]. Huang et al. [16] report that clenbuterol almost prevents the decrease in the weight of gastrocnemius/plantaris muscle bundles induced by dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid. Pellegrino et al. [85] demonstrate that concurrent treatment of clenbuterol with dexamethasone minimizes MHC-transformation-induced by clenbuterol (slow-to-fast) or dexamethasone (fast-to-slow) alone. Thus, β2-AR stimulation plays an inhibitory role in muscle atrophy and weakness induced by catabolic diseases, mechanical unloading, catabolic hormones, and pharmacological agents.

4.3. Response of β2-AR Expression to Catabolic Hormones

Although the effectiveness of β2-AR stimulation on muscle atrophy is well documented, catabolic condition-induced changes in the expression of β2-AR in skeletal muscles are not fully understood. Understanding the responses of β2-AR expression to muscle atrophy is required to establish treatments for muscle atrophy.

Table 1 shows the catabolic-condition-induced changes in β2-AR expression in skeletal muscles. Our group investigated whether catabolic hormones or agents alter β2-AR expression in skeletal muscles [20, 21]. Dexamethasone administration (1.0 mg·kg−1·day−1) to rats for 10 days decreases the expression of β2-AR mRNA in the soleus muscle without altering that in the EDL muscle, although the expression of β2-AR protein in the EDL and soleus muscles is not altered [20, 21]. Dexamethasone also does not alter β2-AR density in gastrocnemius/plantaris muscle bundles [16]. These phenomena are specifically observed in skeletal muscles; meanwhile, glucocorticoids and the GR complex activate the transcription of β2-AR gene in the human hepatoma cell line (HepG2) [48], subsequently leading to the upregulation of β2-AR levels in DDT1 MF-2 smooth muscle cells [50] and lung tissue [16, 51]. Furthermore, dexamethasone decreases the expression of GR mRNA in the soleus muscle [20, 21]. Dexamethasone also decreases and increases the expression of CREB mRNA, a transcription factor of the β2-AR gene [46, 47], in the soleus and EDL muscles, respectively [20]. These findings suggest that the dexamethasone-induced decrease in the expression of β2-AR mRNA in the slow-twitch soleus muscle is associated with transcriptional regulations.

4.4. Response of β2-AR Expression to Muscle Disuse

The effects of physiological and pathological catabolic-condition-induced muscle atrophy on β2-AR expression have also been studied (Table 1) [4, 14, 22]. Our recent investigation demonstrates that casted immobilization (knee and foot arthrodesis) for 10 days markedly induced atrophy in the soleus muscle, whereas it decreased the expression of β2-AR mRNA [22]. Decreased GR mRNA and protein expression was also detected in the soleus muscle [22]. These results suggest that casted immobilization decreases the expression of β2-AR mRNA in slow-twitch muscles via the downregulation of GR levels and subsequent glucocorticoid signals. On the other hand, Ryall et al. [4] demonstrate that aging-induced muscle wasting is observed in the EDL and soleus muscles, although there are no age-associated changes in β2-AR density in these muscles. Furthermore, in the regeneration process from muscle injury induced by bupivacaine injection, β2-AR density and mRNA expression as well as Gαs content are decreased in the soleus but increased in the EDL muscle [14]. Thus, the effects of catabolic conditions such as disuse, aging, and injury on β2-AR expression are different from and/or dependent on the conditions, especially in fast-twitch muscles, whereas decreasing tendencies are observed in slow-twitch muscles.

Both pharmacological and mechanical studies indicate that the preventive effects of β2-AR stimulation on muscle atrophy and weakness are limited by decreased β2-AR synthesis and subsequently decreased density. In order to use β2-adrenergic agonists as a therapeutic agent for muscle wasting, further studies are necessary to obtain detailed evidence regarding the responses of β2-AR expression and function to muscle atrophy.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we discussed adaptive responses of β2-AR expression in skeletal muscles to β2-adrenergic agonist treatment, exercise training, muscle disuse, and glucocorticoid treatment. This paper also outlined the functional roles of β2-AR in skeletal muscles. Skeletal muscle partly requires β2-AR activation for hypertrophy, regeneration, and atrophy prevention; however, its functions and responsiveness must be adaptively regulated by the receptor itself via downregulation, synthesis, and desensitization. New insight in the form of scientific evidence is needed to eradicate sports doping and to identify new therapeutic targets for attenuating muscle atrophy induced by physiological and pathological conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Hideki Suzuki, Department of Health and Physical Education, Aichi University of Education, and Professor Hisaya Tsujimoto, Institute of Health and Sports Science, Kurume University, for their valuable advice and suggestions. This work was supported by Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (2010–2011: S. Sato) and a Grant-in-Aid of the Global Center of Excellence (COE) program, Graduate School of Sport Sciences, Waseda University (2009–2013: K. Imaizumi) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

References

- 1.Kim YS, Sainz RD, Molenaar P, Summers RJ. Characterization of β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in rat skeletal muscles. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1991;42(9):1783–1789. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90516-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams RS, Caron MG, Daniel K. Skeletal muscle β-adrenergic receptors: variations due to fiber type and training. American Journal of Physiology. 1984;246(2, part 1):E160–E167. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1984.246.2.E160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryall JG, Gregorevic P, Plant DR, Sillence MN, Lynch GS. β 2-agonist fenoterol has greater effects on contractile function of rat skeletal muscles than clenbuterol. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;283(6):R1386–R1394. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00324.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryall JG, Plant DR, Gregorevic P, Sillence MN, Lynch GS. β 2-agonist administration reverses muscle wasting and improves muscle function in aged rats. Journal of Physiology. 2004;555(1):175–188. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.056770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burniston JG, Clark WA, Tan LB, Goldspink DF. Dose dependent separation of the hypertrophic and myotoxic effects of the β2 agonist clenbuterol in rat striated muscles. Muscle and Nerve. 2006;33(5):655–663. doi: 10.1002/mus.20504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryall JG, Sillence MN, Lynch GS. Systemic administration of β2-adrenoceptor agonists, formoterol and salmeterol, elicit skeletal muscle hypertrophy in rats at micromolar doses. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;147(6):587–595. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato S, Nomura S, Kawano F, Tanihata J, Tachiyashiki K, Imaizumi K. Effects of the β2-agonist clenbuterol on β1- and β2-adrenoceptor mRNA expressions of rat skeletal and left ventricle muscles. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2008;107(4):393–400. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08097fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S, Nomura S, Kawano F, Tanihata J, Tachiyashiki K, Imaizumi K. Adaptive effects of the β2-agonist clenbuterol on expression of β2-adrenoceptor mRNA in rat fast-twitch fiber-rich muscles. Journal of Physiological Sciences. 2010;60(2):119–127. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosmanov AR, Wong JA, Thomason DB. Duality of G protein-coupled mechanisms for β-adrenergic activation of NKCC activity in skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;283(4):C1025–C1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00096.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abramson SN, Martin MW, Hughes AR, et al. Interaction of β-adrenergic receptors with the inhibitory guanine nucleotide-binding protein of adenylate cyclase in membranes prepared from cyc-S49 lymphoma cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1988;37(22):4289–4297. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Communal C, Colucci WS, Singh K. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway protects adult rat ventricular myocytes against β-adrenergic receptor-stimulated apoptosis. Evidence for Gi-dependent activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(25):19395–19400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910471199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson M. Molecular mechanisms of β2-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2006;117(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krupnick JG, Benovic JL. The role of receptor kinases and arrestins in G protein-coupled receptor regulation. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1998;38:289–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beitzel F, Sillence MN, Lynch GS. β-Adrenoceptor signaling in regenerating skeletal muscle after β-agonist administration. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;293(4):E932–E940. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00175.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ, Sudera DK. Changes in tissue blood flow and β-receptor density of skeletal muscle in rats treated with the β2-adrenoceptor agonist clenbuterol. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1987;90(3):601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H, Gazzola C, Pegg GG, Sillence MN. Differential effects of dexamethasone and clenbuterol on rat growth and on β2-adrenoceptors in lung and skeletal muscle. Journal of Animal Science. 2000;78(3):604–608. doi: 10.2527/2000.783604x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sillence MN, Matthews ML, Spiers WG, Pegg GG, Lindsay DB. Effects of clenbuterol, ICI118551 and sotalol on the growth of cardiac and skeletal muscle and on β2-adrenoceptor density in female rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 1991;344(4):449–453. doi: 10.1007/BF00172585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieto JL, Diaz-Laviada I, Malpartida JM, Galve-Roperh I, Haro A. Adaptations of the β-adrenoceptor-adenylyl cyclase system in rat skeletal muscle to endurance physical training. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 1997;434(6):809–814. doi: 10.1007/s004240050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckenmeyer PJ, Goldfarb AH, Partilla JS, Pineyro MA, Dax EM. Endurance training, not acute exercise, differentially alters β-receptors and cyclase in skeletal fiber types. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258(1):E71–E77. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.1.E71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato S, Shirato K, Tachiyashiki K, Imaizumi K. Synthesized glucocorticoid, dexamethasone regulates the expressions of β2-adrenoceptor and glucocorticoid receptor mRNAs but not proteins in slow-twitch soleus muscle of rats. Journal of Toxicological Sciences. 2011;36(4):479–486. doi: 10.2131/jts.36.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawano F, Tanihata J, Sato S, et al. Effects of dexamethasone on the expression of β1-, β2- and β3-adrenoceptor mRNAs in skeletal and left ventricle muscles in rats. Journal of Physiological Sciences. 2009;59(5):383–390. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato S, Suzuki H, Tsujimoto H, Shirato K, Tachiyashiki K, Imaizumi K. Casted-immobilization downregulates glucocorticoid receptor expression in rat slow-twitch muscle. Life Sciences. in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lynch GS, Ryall JG. Role of β-adrenoceptor signaling in skeletal muscle: implications for muscle wasting and disease. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(2):729–767. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryall JG, Lynch GS. The potential and the pitfalls of β-adrenoceptor agonists for the management of skeletal muscle wasting. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2008;120(3):219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YS, Sainz RD. β-adrenergic agonists and hypertrophy of skeletal muscles. Life Sciences. 1992;50(6):397–407. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinkle RT, Hodge KMB, Cody DB, Sheldon RJ, Kobilka BK, Isfort RJ. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and anti-atrophy effects of clenbuterol are mediated by the β2-adrenergic receptor. Muscle and Nerve. 2002;25(5):729–734. doi: 10.1002/mus.10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costelli P, Garcia-Martinez C, Llovera M, et al. Muscle protein waste in tumor-bearing rats is effectively antagonized by a β2-adrenergic agonist (clenbuterol). Role of the ATP-ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic pathway. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95(5):2367–2372. doi: 10.1172/JCI117929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busquets S, Figueras MT, Fuster G, et al. Anticachectic effects of formoterol: a drug for potential treatment of muscle wasting. Cancer Research. 2004;64(18):6725–6731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harcourt LJ, Schertzer JD, Ryall JG, Lynch GS. Low dose formoterol administration improves muscle function in dystrophic mdx mice without increasing fatigue. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2007;17(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kline WO, Panaro FJ, Yang H, Bodine SC. Rapamycin inhibits the growth and muscle-sparing effects of clenbuterol. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2007;102(2):740–747. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00873.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navegantes LCC, Resano NMZ, Migliorini RH, Kettelhut C. Catecholamines inhibit Ca2+-dependent proteolysis in rat skeletal muscle through β2-adrenoceptors and cAMP. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;281(3):E449–E454. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.3.E449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi H, Zeng C, Ricome A, Hannon KM, Grant AL, Gerrard DE. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway is differentially involved in β-agonist-induced hypertrophy in slow and fast muscles. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;292(5):C1681–C1689. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00466.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitaura T, Tsunekawa N, Hatta H. Decreased monocarboxylate transporter 1 in rat soleus and EDL muscles exposed to clenbuterol. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001;91(1):85–90. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens L, Firinga C, Gohlsch B, Bastide B, Mounier Y, Pette D. Effects of unweighting and clenbuterol on myosin light and heavy chains in fast and slow muscles of rat. American Journal of Physiology. 2000;279(5):C1558–C1563. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yimlamai T, Dodd SL, Borst SE, Park S. Clenbuterol induces muscle-specific attenuation of atrophy through effects on the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99(1):71–80. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00448.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearen MA, Ryall JG, Maxwell MA, Ohkura N, Lynch GS, Muscat GEO. The orphan nuclear receptor, NOR-1, is a target of β-adrenergic signaling in skeletal muscle. Endocrinology. 2006;147(11):5217–5227. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearen MA, Myers SA, Raichur S, Ryall JG, Lynch GS, Muscat GEO. The orphan nuclear receptor, NOR-1, a target of β-adrenergic signaling, regulates gene expression that controls oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):2853–2865. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawasaki E, Hokari F, Sasaki M, Sakai A, Koshinaka K, Kawanaka K. The effects of β-adrenergic stimulation and exercise on NR4A3 protein expression in rat skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiological Sciences. 2010;61(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12576-010-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3(9):639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Claing A, Laporte SA, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Endocytosis of G protein-coupled receptors: roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and ß-arrestin proteins. Progress in Neurobiology. 2002;66(2):61–79. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCormick C, Alexandre L, Thompson J, Mutungi G. Clenbuterol and formoterol decrease force production in isolated intact mouse skeletal muscle fiber bundles through a β2-adrenoceptor-independent mechanism. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2010;109(6):1716–1727. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00592.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones SW, Baker DJ, Greenhaff PL. G protein-coupled receptor kinases 2 and 5 are differentially expressed in rat skeletal muscle and remain unchanged following β2-agonist administration. Experimental Physiology. 2003;88(2):277–284. doi: 10.1113/eph8802472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. β-arrestins and cell signaling. Annual Review of Physiology. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore CAC, Milano SK, Benovic JL. Regulation of receptor trafficking by GRKs and arrestins. Annual Review of Physiology. 2007;69:451–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Multifaceted roles of β-arrestins in the regulation of seven-membrane-spanning receptor trafficking and signalling. Biochemical Journal. 2003;375(3):503–515. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins S, Bouvier M, Bolanowski MA, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. cAMP stimulates transcription of the β2-adrenergic receptor gene in response to short-term agonist exposure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86(13):4853–4857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collins S, Altschmied J, Herbsman O, Caron MG, Mellon PL, Lefkowitz RJ. A cAMP response element in the β2-adrenergic receptor gene confers transcriptional autoregulation by cAMP. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265(31):19330–19335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornett LE, Hiller FC, Jacobi SE, Cao W, McGraw DW. Identification of a glucocorticoid response element in the rat β2-adrenergic receptor gene. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54(6):1016–1023. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bengtsson T, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Differential adrenergic regulation of the gene expression of the β-adrenoceptor subtypes β1, β2 and β3 in brown adipocytes. Biochemical Journal. 2000;347(3):643–651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadcock JR, Malbon CC. Regulation of β-adrenergic receptors by “permissive” hormones: glucocorticoids increase steady-state levels of receptor mRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(22):8415–8419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mak JCW, Nishikawa M, Shirasaki H, Miyayasu K, Barnes PJ. Protective effects of a glucocorticoid on downregulation of pulmonary β2-adrenergic receptors in vivo. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96(1):99–106. doi: 10.1172/JCI118084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Port JD, Huang LY, Malbon CC. β-Adrenergic agonists that down-regulate receptor mRNA up-regulate a M(r) 35,000 protein(s) that selectively binds to β-adrenergic receptor mRNAs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(33):24103–24108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tholanikunnel BG, Granneman JG, Malbon CC. The M(r) 35,000 β-adrenergic receptor mRNA-binding protein binds transcripts of G-protein-linked receptors which undergo agonist-induced destabilization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(21):12787–12793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pende A, Tremmel KD, DeMaria CT, et al. Regulation of the mRNA-binding protein AUF1 by activation of the β-adrenergic receptor signal transduction pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(14):8493–8501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blaxall BC, Pellett AC, Wu SC, Pende A, Port JD. Purification and characterization of β-adrenergic receptor mRNA-binding proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(6):4290–4297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baar K, Esser K. Phosphorylation of p70(S6k) correlates with increased skeletal muscle mass following resistance exercise. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276(1):C120–C127. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tesch PA, Karlsson J. Muscle fiber types and size in trained and untrained muscles of elite athletes. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1985;59(6):1716–1720. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.6.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong TS, Booth FW. Sekeletal muscle enlargement with weight-lifting exercise by rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1988;65(2):950–954. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.2.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Colliander EB, Tesch PA. Effects of eccentric and concentric muscle actions in resistance training. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1990;140(1):31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1967;242(9):2278–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holloszy JO, Oscai LB, Don IJ, Molé PA. Mitochondrial citric acid cycle and related enzymes: adaptive response to exercise. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1970;40(6):1368–1373. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pette D, Heilmann C. Transformation of morphological, functional and metabolic properties of fast twitch muscle as induced by long term electrical stimulation. Basic Research in Cardiology. 1977;72(2-3):247–253. doi: 10.1007/BF01906369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staron RS, Hikida RS, Hagerman FC. Human skeletal muscle fiber type adaptability to various workloads. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1984;32(2):146–152. doi: 10.1177/32.2.6229571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mounier R, Cavalié H, Lac G, Clottes E. Molecular impact of clenbuterol and isometric strength training on rat EDL muscles. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 2007;453(4):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lynch GS, Hayes A, Campbell SP, Williams DA. Effects of β2-agonist administration and exercise on contractile activation of skeletal muscle fibers. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;81(4):1610–1618. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Powers SK, Wade M, Criswell D, et al. Role of beta-adrenergic mechanisms in exercise training-induced metabolic changes in respiratory and locomotor muscle. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 1995;16(1):13–18. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torgan CE, Etgen GJ, Brozinick JT, Jr., Wilcox RE, Ivy JL. Interaction of aerobic exercise training and clenbuterol: effects on insulin-resistant muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;75(4):1471–1476. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Torgan CE, Brozinick JT, Jr., Banks EA, Cortez MY, Wilcox RE, Ivy JL. Exercise training and clenbuterol reduce insulin resistance of obese Zucker rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264(3):E373–E379. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.3.E373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miura S, Kawanaka K, Kai Y, et al. An increase in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) mRNA in response to exercise is mediated by β-adrenergic receptor activation. Endocrinology. 2007;148(7):3441–3448. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Handschin C, Rhee J, Lin J, Tarr PT, Spiegelman BM. An autoregulatory loop controls peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α expression in muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(12):7111–7116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232352100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akimoto T, Pohnert SC, Li P, et al. Exercise stimulates Pgc-1α transcription in skeletal muscle through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(20):19587–19593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98(1):115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barbier J, Rannou-Bekono F, Marchais J, Berthon PM, Delamarche P, Carré F. Effect of training on β1β2β3 adrenergic and M2 muscarinic receptors in rat heart. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2004;36(6):949–954. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000128143.93407.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stones R, Natali A, Billeter R, Harrison S, White E. Voluntary exercise-induced changes in β2-adrenoceptor signalling in rat ventricular myocytes. Experimental Physiology. 2008;93(9):1065–1075. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogasawara J, Sanpei M, Rahman N, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor trafficking by exercise in rat adipocytes: roles of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase-2, β-arrestin-2, and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. FASEB Journal. 2006;20(2):350–352. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4688fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kizaki T, Takemasa T, Sakurai T, et al. Adaptation of macrophages to exercise training improves innate immunity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;372(1):152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martin WH, Coggan AR, Spina RJ, Saffitz JE. Effects of fiber type and training on β-adrenoceptor density in human skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257(5):E736–E742. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.257.5.E736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farrar RP, Monnin KA, Fordyce DE, Walters TJ. Uncoupling of changes in skeletal muscle β-adrenergic receptor density and aerobic capacity during the aging process. Aging. 1997;9(1-2):153–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03340141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herrera NM, Jr., Zimmerman AN, Dykstra DD, Thompson LV. Clenbuterol in the prevention of muscle atrophy: a study of hindlimb-unweighted rats. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2001;82(7):930–934. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zeman RJ, Ludemann R, Etlinger JD. Clenbuterol, a β2-agonist, retards atrophy in denervated muscles. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252(1):E152–E155. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.252.1.E152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beitzel F, Gregorevic P, Ryall JG, Plant DR, Sillence MN, Lynch GS. β 2-adrenoceptor agonist fenoterol enhances functional repair of regenerating rat skeletal muscle after injury. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2004;96(4):1385–1392. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01081.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith IJ, Alamdari N, O’Neal P, Gonnella P, Aversa Z, Hasselgren PO. Sepsis increases the expression and activity of the transcription factor Forkhead Box O 1 (FOXO1) in skeletal muscle by a glucocorticoid-dependent mechanism. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2010;42(5):701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao W, Qin W, Pan J, Wu Y, Bauman WA, Cardozo C. Dependence of dexamethasone-induced Akt/FOXO1 signaling, upregulation of MAFbx, and protein catabolism upon the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;378(3):668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sun X, Fischer DR, Pritts TA, Wray CJ, Hasselgren PO. Expression and binding activity of the glucocorticoid receptor are upregulated in septic muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;282(2):R509–R518. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00509.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pellegrino MA, D’Antona G, Bortolotto S, et al. Clenbuterol antagonizes glucocorticoid-induced atrophy and fibre type transformation in mice. Experimental Physiology. 2004;89(1):89–100. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2003.002609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]