Abstract

Beta-amyloid plaques (Aβ plaques) in the brain are associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Imaging agents that could target the Aβ plaques in the living human brain would be potentially valuable as biomarkers in patients with CAA. A new series of 18F styrylpyridine derivatives with high molecular weights for selectively targeting Aβ plaques in the blood vessels of the brain, but excluded from the brain parenchyma is reported. The styrylpyridine derivatives, 8a–c, display high binding affinities and specificity to Aβ plaques (Ki = 2.87 nM, 3.24 and 7.71 nM, respectively). In vitro autoradiography of [18F]8a shows labeling of β-amyloid plaques associated with blood vessel walls in human brain sections of subjects with CAA, and also in the tissue of AD brain sections. The results suggest that [18F]8a may be a useful PET imaging agent for selectively detecting Aβ plaques associated with cerebral vessels in the living human brain.

Keywords: PET imaging, Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral blood vessels, β–amyloid plaque, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, autoradiography and in vivo biodistribution

Introduction

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a common cause of stroke and dementia in older people. Patients typically present pathological symptoms associated with lobar intracranial macrohemorrhages or microbleeds. Postmortem studies suggest that there are distinctive morphological changes in the cerebral vessels including the deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide aggregates, of which Aβ peptides are the most common1,2. The depositions are located in small to medium-sized cerebral and leptomeningeal arteries and less prominently in the walls of capillaries and veins. Similar to the deposition of Aβ in the parenchymal brain tissue in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the Aβ peptides form Aβ aggregates and neurofibrillary plaques are accumulated in the cerebral blood vessels. As the deposition of Aβ aggregates increases with time, they become hardened. These changes in the cerebral blood vessels lead to microbleeds3–6. It has been estimated that CAA is present in 55 – 59% of dementia patients. At least 30% of the dementia patients showed severe CAA, as compared to 7 – 24% in non-demented patients7,8. In general, there is a very close, but not parallel, relationship between CAA and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). They also share a set of common genetic risk factors. It is believed that there are specific mechanism(s), which put age-related cerebrovascular degeneration at a critical point in the pathogenesis of AD9,10. Evidence collected from postmortem examination of brain tissues from CAA and AD patients found Aβ deposition in the parenchymal and cortical arteries of the brains of AD subjects, while in CAA patients the same deposition was visible predominantly in the blood vessels11,12.

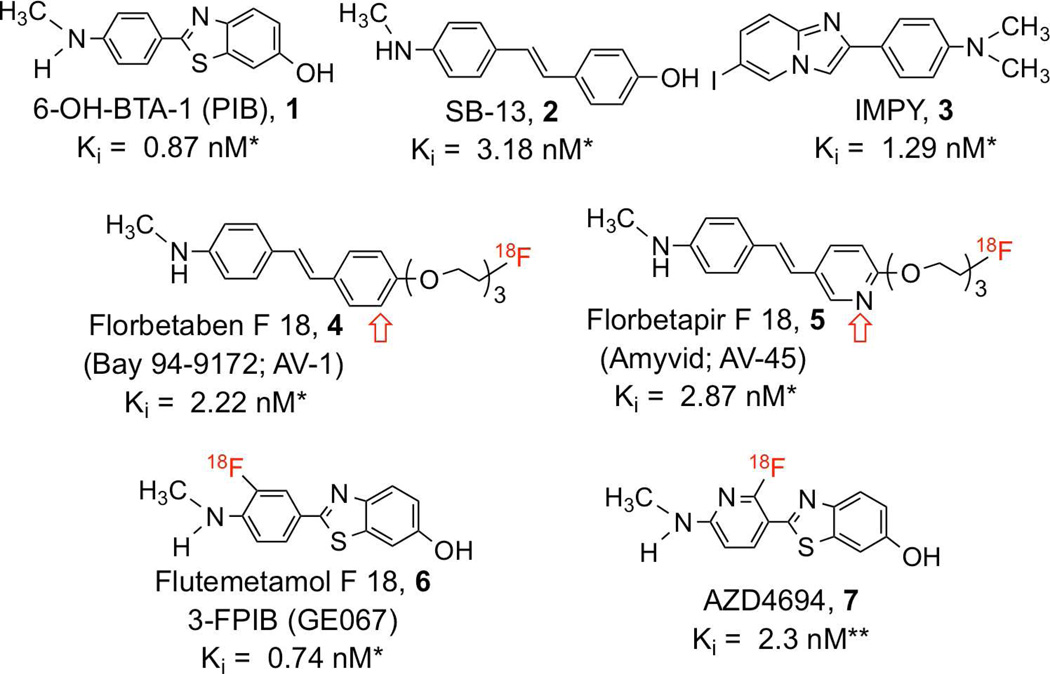

Imaging Aβ-plaques in the brain is generally accepted as a potential useful tool for studying the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases associated with the formation of β-amyloid. One of the leading protocols is [11C]PIB ([11C]1) (Pittsburgh Compound B)/PET imaging of Aβ plaques in the living brain13–16. Recently, several reports on [11C]1/PET imaging in CAA and post-stroke patients suggested that Aβ depositions could be detected in the brain tissue as well as in the blood vessels6,13,17–19. Since 1 is a small molecule, it readily penetrates the intact blood-brain barrier; therefore, [11C]1/PET images of the Aβ deposition represents the map of total Aβ deposition in the brain, as well as in the cerebral vessels.

To improve the availability of PET tracers for routine clinical practice, several 18F Aβ-plaque imaging agents, including [18F]florbetapir f 18 ([18F]AV-45, [18F]5)20–24, [18F]florbetaben f 18 ([18F]AV-1, BAY-94-9172, [18F]4)25–28, [18F]flutemetamol f 18 ([18F]FPIB, GE067, [18F]6)29–33 and 2-(2-([18F]fluoro)-6-methylaminopyridin-3-yl)benzofuran-5-ol ([18F]AZD4694, [18F]7)34 have been developed and found to be useful PET agents for targeting Aβ plaques in the brain. The phase III clinical trial for [18F]5 has been completed24, and this Aβ-plaque targeting imaging agent is currently under regulatory review for approval. Similar to [11C]1, [18F]5 labels all Aβ plaques, those deposited in the parenchymal of the brain, as well as those in the cerebrovascular vessels. In order to differentially diagnose the CAA related accumulation of Aβ plaques, a [18F] labeled Aβ-plaque imaging agent for specifically detecting Aβ deposition located on the wall of cerebral blood vessels is needed.

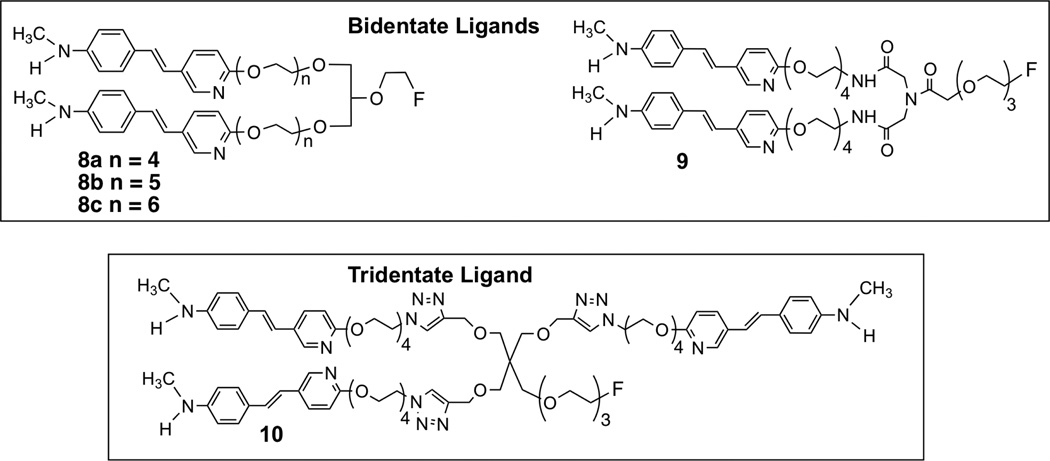

In order to be able to differentiate between Aβ plaques in the brain and those on the wall of cerebrovascular vessels, a series of [18F] imaging agents containing two styrylpyridine cores separated by long pegylated chains (n > 8) was prepared and tested. We reasoned that the “bivalent or trivalent ligands” containing two or three styrylpyridine binding cores would retain a high binding affinity towards the Aβ plaques due to the presence of multiple binding sites within the repeated β-sheet structure. It is probable that the multi-dentate styrylpyridine derivatives with the appropriate spacing between the binding moieties would display good binding to the Aβ aggregates, and that they would be unable to penetrate the intact blood-brain barrier (BBB) in vivo due to their high molecular weights, which exceed 600, a general cutoff point for a simple and neutral molecule to penetrate the BBB by diffusion21. Therefore, the “bidentate or tridentate ligands”, 8, 9 and 10, would likely bind only to the Aβ aggregates located outside of the blood-brain barrier on the vessel walls in CAA patients.

Reported herein is the synthesis and characterization of several Aβ aggregate-binding ligands, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10, which do not cross the intact blood brain barrier, and therefore may specifically target Aβ aggregates located on the cerebrovascular vessel walls outside of the BBB of CAA subjects.

Results

Chemical synthesis of bivalent and trivalent styrylpyridine derivatives, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10

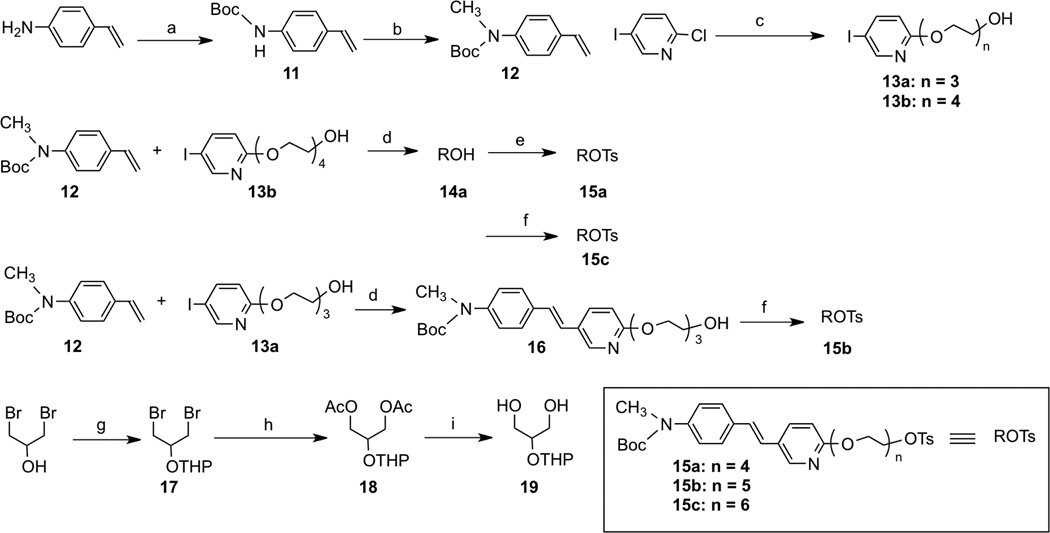

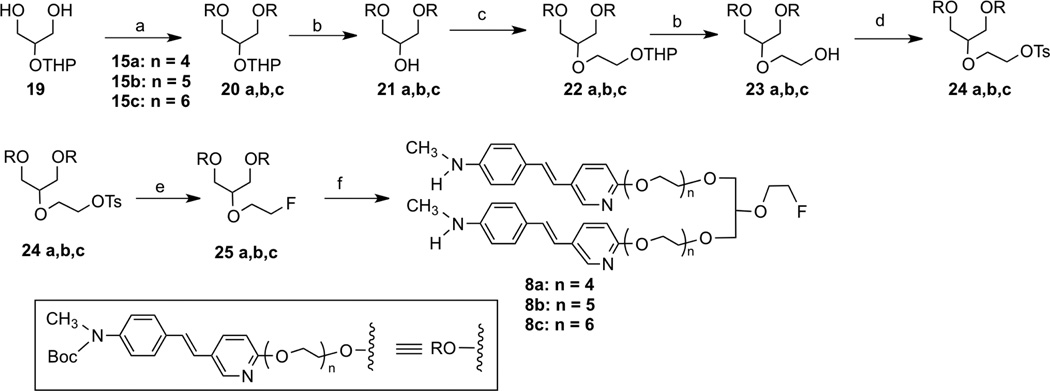

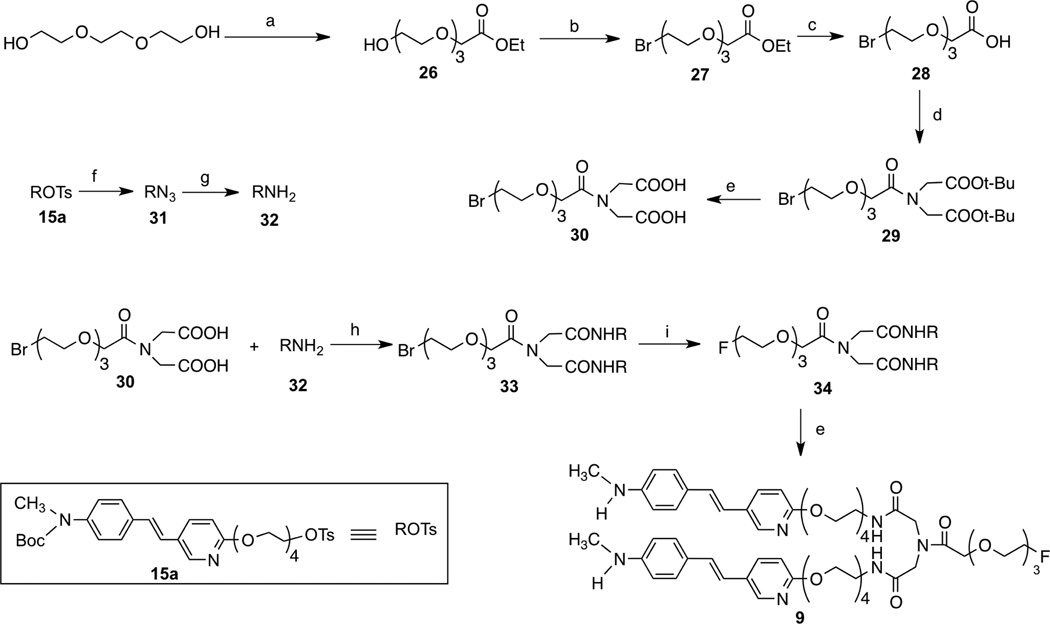

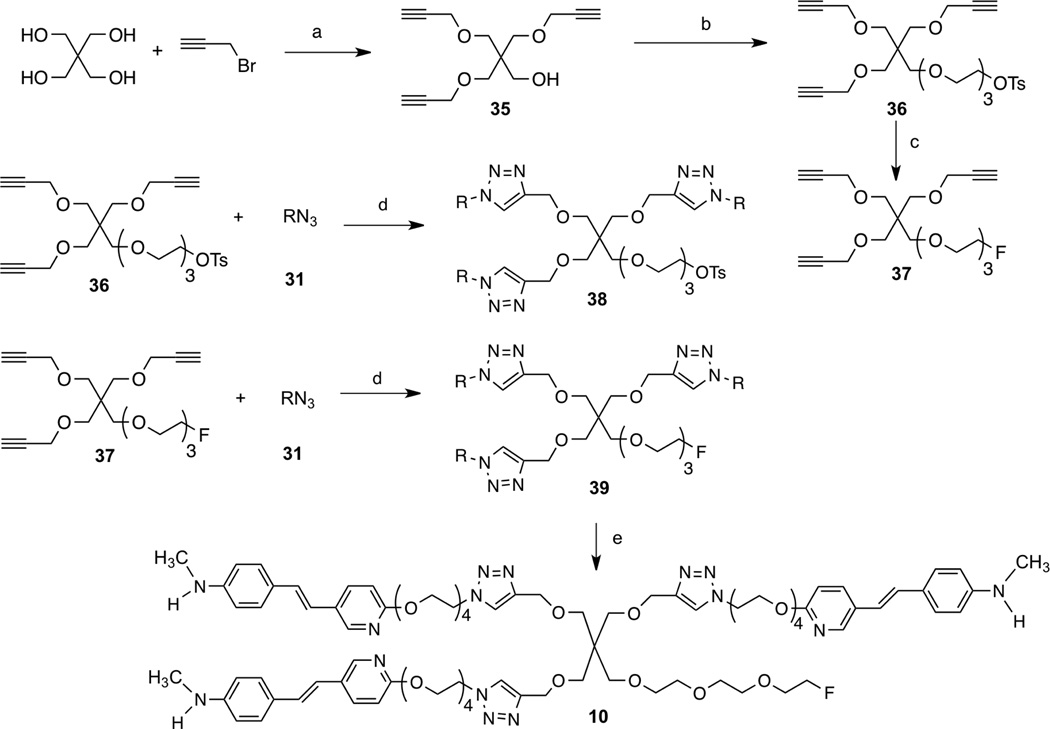

The synthesis of the 5 derivatives, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10, with two (bivalent ligand) or three (trivalent ligand) styrylpyridine binding moieties tethered by a polyethylene glycol chain was successfully achieved as described in schemes 1, 2, 3 and 4. For the first series of bivalent ligands, compound 8, the binding core, styrylpyridine, was attached with different chain lengths of polyethylene glycol (8a, 8b, 8c, n = 4, 5 or 6). The hydroxyl ends of the polyethylene glycol tethered with styrylpyridines were attached to the 1 and 3-hydroxy positions of a glycerol. The 2-hydroxyl group of the glycerol was linked to an ethylene glycol group leaving one free hydroxyl group, through which the fluorine atom was end-capped. The molecule has an achiral center and the hydroxyl groups of the glycerol provided a convenient way of stretching between the two styrylpyridine cores with poly-pegylated chains while leaving one more site for an additional ethylene glycol group for [18F] labeling. We chose to use ether linkage (for 8a, 8b, 8c) or amide linkage (for 9) instead of carboxyl esters, in consideration of in vivo stability. However, the character of the linkage bond, ether vs amide, apparently has a dramatic effect on the in vitro binding affinity to the Aβ plaques, see discussion below. We also used “click chemistry” to explore the feasibility of constructing a tridentate ligand, 10, in which three styrylpyridine cores would be included in one single molecule.

Scheme 1.

Ragent and conditions: (a) (Boc)2O, H2O, 35 °C; (b) NaH, CH3I, DMF, rt; (c) triethylene glycol, CsCO3, DMF, 150 °C; (d) K2CO3, Bu4NBr, Pd(OAc)2. DMF, 60 °C; (e) TsCl, Et3N, DMAP, DCM, rt; (f) diethylene glycol ditosylate, NaH, DMF, rt; (g) DHP, PPTS, EtOH, rt; (h)K2CO3.Bu4NI, Bu4NOAc, ACN; (i) NH3, CH3OH.

Scheme 2.

Ragent and conditions: (a) NaH, 2 eq. 15, DMF, rt; (b)PPTS, EtOH; (c) NaH, 2-(2-bromoethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran, DMF, rt; (d) TsCl, Et3N, DMAP, DCM, rt; (e) TBAF, THP, 70°C; (f) TFA, rt.

Scheme 3.

Ragent and conditions: (a)N2CHCO2C2H5, BF3 Et2O, DCM, 0 °C, (b)NBS PPh3, DCM, 0 °C, (c)NaOH, THF, rt; (d)HOBt, EDCI, DIPEA, ditert-butyl iminodiacetate, DMF rt; (e) TFA, rt; (f) NaN3, DMF, 60°C; (g)PPh3, H2O, THF, 60°C; (h) DCC, DMAP, DCM, rt; (i) TBAF, THF, 70 °C.

Scheme 4.

Ragent and conditions: (a)40% NaOH, DMSO, rt; (b) NaH, tri ethylene glycol di(p-toluenesulfonate), DMF, rt; (c) TBAF, THF, 70 °C; (e)sodium ascorbate, CuSO4, t-BuOH, H2O, rt; (f) TFA, rt.

The intermediates 11 – 19, 26 and 35 were readily prepared according to similar reported methods35–37. Using the Williamson ether synthesis method, di-alcohol 19 and tosylates 15 were stitched together (Scheme 1) and the key bivalent intermediates 20a – c were synthesized in good yields. Following a six-step transformation, fluoroethoxy group tethered bivalent styrylpyridine derivatives, 8a – c, were obtained (Scheme 2). For the synthesis of the other bivalent styrylpyridine derivative, 9, linked via amide bonds, the key intermediates, amine 32 and di-acid 30 were prepared first, followed by a 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate/ N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (HOBt/EDCI) promoted coupling reaction. The intermediate 33 was employed as the starting material for fluorination, and subsequently the Boc protection group was removed to give 9 in an acceptable yield.

For preparation of a tri-dentate ligand we decided to use pentaerythritol as the backbone structure (Scheme 4). Three of the hydroxyl groups were reacted with propargyl bromide leaving one hydroxyl group for additional pegylation (n = 3). The end of the tri-glycolated hydroxyl group was capped with a fluorine atom. To assemble the targeted tridentate ligand, 10, containing three 1,2,3-triazole rings, “click chemistry” between azide and alkyne was carried out. The desired intermediate 37 was first prepared through a simple three-step sequence. At this stage, copper-catalyzed “click chemistry”38 was utilized to assemble the styrylpyridine polyethylene glycol-trimerized intermediates 38 and 39. The final product, trivalent ligand 10, was obtained by a simple acidic de-protection of intermediate 39.

Two HPLC conditions were used to test the purity of the final compounds, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10. Using a Phenomenex Luna 5µ C18 250 × 4.60 mm column, eluted with ACN/water, 8/2, 1 min/mL or a Phenomenex Luna 5µ C18 250 × 4.60 mm column, eluted with MeOH/water, 9/1, 1 min/mL. All of the final tested samples showed a purity > 95%. The HPLC profiles are included in the supplemental information section.

In vitro binding studies of [18F]5 to Aβ-aggregates in the AD brain tissue homogenates

An in vitro binding assay was employed to measure the inhibition of [18F]5 binding to Aβ-aggregates in the AD brain tissue homogenates (see supplemental information). Inhibition constants (Ki, nM) of various agents against the binding of [18F]5 to Aβ-aggregates are shown in Table 1. In addition, standard ligands, such as 1, 4, 5 and 6 were tested in the same binding assay (see Table 1). As expected, high binding affinities were obtained for the known compounds within the range of < 5 nM. The glycerol-based bivalent ligands, 8a, 8b and 8c, displayed excellent binding affinities (Ki = 3.24, 7.71 and 3.86 nM, respectively). It appears that the chain length of the pegylation has no affect on the binding affinity. The Ki values (3 – 7 nM) were comparable when the chain length was 4, 5 or 6. However, the amide-based bivalent ligand, 9, showed a significantly lower affinity, Ki = 71.2 nM. The amide linkage is apparently not suitable for designing this series of bivalent ligand. The trivalent ligand, 10, also displayed a dramatically low binding affinity, Ki = 468 nM.

Table 1.

Inhibition constants (Ki, nM) of Aβ plaques targeting ligands against binding of [18F]5 to Aβ plaques in postmortem AD brain homogenates.

| Compound Name | Ki (nM) | Compound Name | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PIB, 1 | 0.87 ± 0.18 | 8a (n = 4) | 3.24 ± .92 |

| SB-13, 2 | 3.18 ± 1.04 | 8b (n = 5) | 7.71 ± 3.56 |

| IMPY, 3 | 1.29 ± 0.46 | 8c (n = 6) | 3.86 ± 1.05 |

| florbetaben (AV-1), 4 | 2.22 ± 0.54 | 25a | > 1,000 |

| florbetapir (AV-45), 5 | 2.87 ± 0.17 | 9 (n = 3) | 71.2 ± 16.8 |

| flutemetamol (3-FPIB), 6 | 0.74 ± 0.38 | 10 | 468 |

*22

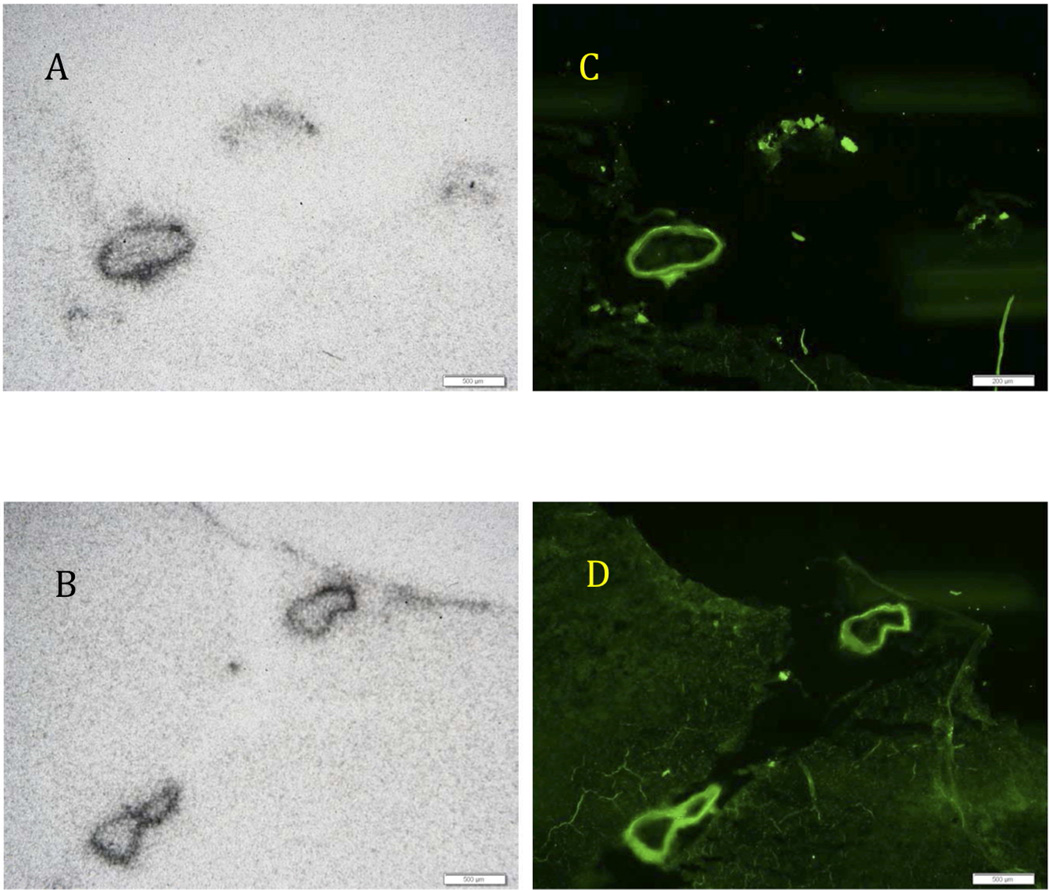

Radiolabeling of bivalent and trivalent styrylpyridine derivatives, [18F]8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10

The radiolabeling of the bidentate and tridentate ligands, 8a – c, 9 and 10, was successfully performed using the same protocol as reported for the preparation of [18F]5 (see scheme 5 and Fig. 3)22. The labeling yields (about 30% EOS) were comparable to that observed for [18F]5, and the radiochemical purity was > 98%.

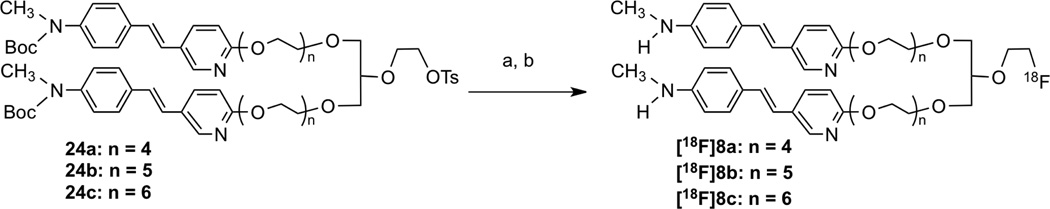

Scheme 5.

Ragent and conditions: (a) Na[18F]floride, K[2,2,2]/K2CO3; (b) 6N HCl

Figure 3.

HPLC profiles of [18F]8a and co-injected cold standard 8a on a reversed phase Gemini C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm) with the following gradient and a flow rate of 1 mL/min: 0 – 2 minutes 100% ammonium format buffer (10 mM); 2 – 5 minutes ammonium formate buffer 100% - 30%, ACN 0% – 70%; 5 –10 minutes ammonium formate buffer 30% - 0%, ACN 70% – 100%; 10 – 15 minutes 0% –100% ammonium formate buffer, 100% - 0% ACN; 15 – 18 minutes 100% ammonium formate buffer.

Autoradiography of postmortem brain tissue sections with [18F]5 and [18F]8a

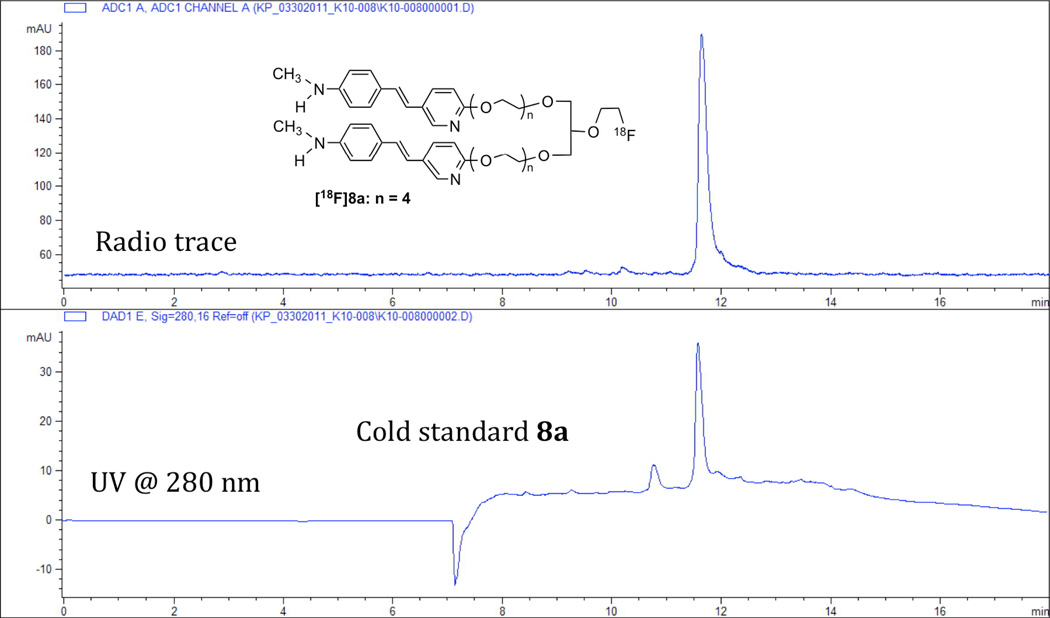

When confirmed CAA brain sections were incubated with [18F]8a, the resulting autoradiogram clearly demonstrated a selective and highly dense labeling of the Aβ plaques of cerebral blood vessels with low labeling in the other areas of the brain sections (see Figure 4 upper panel). The labeling in the CAA brain sections was highly discrete. It is likely that in the CAA brain only the walls of cerebral blood vessels contained Aβ plaques; therefore the [18F]8a only accumulated in these areas. For comparison, AD and healthy control (HC) brain sections were also labeled with [18F]5 or [18F]8a. As expected, in the AD brain sections, which contained Aβ plaques in both the parenchymal tissue and the blood vessels, the sections were labeled intensely by both tracers. Due to a lack of Aβ plaques, both tracers showed very low labeling in the healthy control (HC) brain sections (Figure 4 lower panel).

Figure 4.

In the upper panel the autoradiography of postmortem human brain sections of occipital samples from cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) using the new bivalent ligand, [18F]8a, showed a highly distinctive labeling at the blood vessels. Other brain parenchymal regions displayed very little labeling, which suggests that there was a selective accumulation of Aβ plaques in the vessel walls in this CAA patient. The lower panel shows brain sections of AD and healthy control (HC) subjects using either [18F]AV-45 ([18F]5) or [18F]8a. The AD brain section showed highly significant labeling of Aβ plaques, while both tracers showed little or no binding in the HC sections.

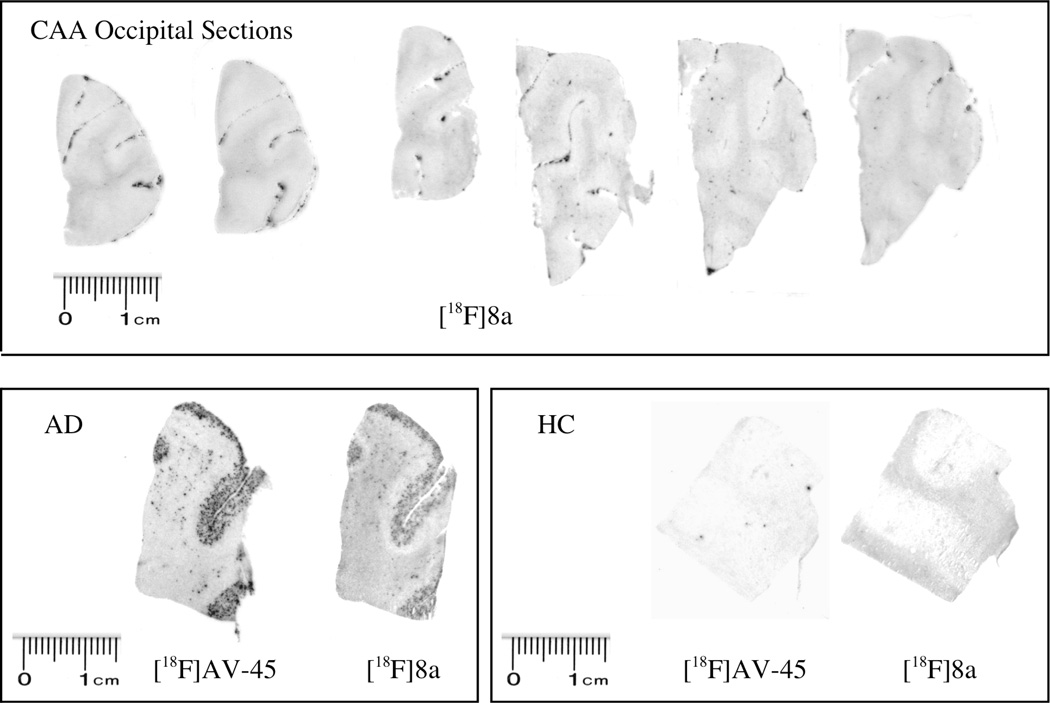

To further confirm the nature of the Aβ plaque-labeling of CAA brain sections, a comparison experiment between autoradiography of [18F]8a (Figure 5A and B) and fluorescent staining with thioflavin S (Figure 5C and D) was performed using neighboring CAA occipital brain sections. The results clearly indicate that the same labeling of the major blood vessels was observed with thioflavin S as with [18F]8a. The data support the conclusion that [18F]8a labeled Aβ plaques located on the major blood vessels in the CAA brain (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Autoradiography of postmortem human brain samples of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) using [18F]8a (A and B), which displayed excellent labeling of Aβ aggregates of the blood vessel walls. There was prominent labeling of major blood vessels only in the CAA brain sections. It is apparent that the parenchymal brain tissue had no Aβ plaques, therefore no labeling was observed. When the neighboring sections were labeled with thioflavin S (C and D), the fluorescent images displayed a matching staining of blood vessel walls comparable to the images from the autoradiography of [18F]8a. The results strongly suggest that [18F]8a labeled the Aβ aggregates of the blood vessel walls. The white bars represent a scale of 500 µm.

In vivo biodistribution in mice

After an iv injection in normal mice, [18F]8a, 8b and 8c showed relatively low brain uptake ranging between 0.3 to 0.4 % dose/gram at 2 min (Table 2). In comparison to the brain uptake of [18F]5, which showed 7.8 % dose/gram at 2 min, the bidentate ligands, [18F]8a, 8b and 8c, clearly displayed a very low brain penetration. The low brain penetration of these new tracers would enable the selective labeling of Aβ plaques located on the major blood vessels in the CAA brain.

Table 2.

Comparison of the biodistributions of [18F]8a, [18F]8b, [18F]8c and [18F] 5) in normal mice (% dose/gram).

| [18F]8a | [18F]5 | |||

| Organ | 2 min n = 6 |

30 min n = 6 |

2 min* n = 3 |

30 min* n = 3 |

| Blood | 4.77 ± 1.25 | 1.54 ± 0.12 | 3.14 ± 0.69 | 2.80 ± 0.44 |

| Muscle | 0.82 ± 0.16 | 1.21 ± 0.15 | 1.06 ± 0.39 | 1.78 ± 0.34 |

| Kidney | 8.13 ± 0.73 | 9.36 ± 0.42 | 10.9 ± 2.63 | 6.31 ± 0.58 |

| Liver | 21.2 ± 1.58 | 21.4 ± 2.24 | 21.5 ± 1.07 | 12.9 ± 0.72 |

| Brain | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 7.77 ± 1.70 | 1.59 ± 0.22 |

| Bone | 1.30 ± 0.23 | 2.34 ± 0.80 | 1.43 ± 0.09 | 1.22 ± 0.17 |

| [18F]8b | [18F]8c | |||

| Organ | 2 min n = 6 |

30 min n = 6 |

2 min n = 6 |

30 min n = 6 |

| Blood | 2.55 ± 0.21 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 3.12 ± 0.17 | 1.40 ± 0.10 |

| Muscle | 1.30 ± 0.70 | 1.62 ± 0.39 | 0.65 ± 0.22 | 1.29 ± 0.12 |

| Kidney | 14.9 ± 0.86 | 13.4 ± 1.84 | 13.7 ± 2.15 | 11.7 ± 0.57 |

| Liver | 33.5 ± 6.60 | 20.0 ± 6.48 | 30.2 ± 3.47 | 16.0 ± 1.91 |

| Brain | 0.40 ± 0.10 | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.04 |

| Bone | 1.64 ± 0.44 | 1.80 ± 0.57 | 1.06 ± 0.11 | 1.36 ± 0.12 |

About 925 KBq of each ligand in a saline solution was injected. Mice were sacrificed at 2 and 30 minutes post injection22.

Discussion

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) share common risk factors – mainly the accumulation of Aβ aggregates. It is generally believed that the pathology of CAA is associated with the deposit of β-amyloid on the walls of the cortical and leptomenigeal blood vessels. In addition to being a disease-defining pathological marker of AD, Aβ plaques are believed to play a significant role in the pathophysiological mechanisms associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. The ability to use PET imaging to determine the location and concentration of Aβ aggregates would be useful for diagnostic purposes.

There are two major pre-requisites for imaging agents targeting Aβ plaques associated with cerebral blood vessel walls: 1. High binding affinity to Aβ plaques: To evaluate the feasibility of new ligands targeting the Aβ plaques of cerebral blood vessel walls suitable as CAA imaging agents, we employed an in vitro assay using AD brain tissue homogenates against the binding of [18F]5 to measure the binding affinity. 2. Selective labeling of Aβ plaques on cerebral blood vessel walls and not in the cerebral parenchymal tissue: Preliminary testing of this requirement was based on biodistribution (brain uptake at 2 min after an iv injection) of [18F] labeled ligands in normal mice. We reasoned that the inability of the new ligands to penetrate the intact blood-brain barrier (BBB) supported the conclusion that they would label only Aβ plaques on cerebral blood vessel walls, located outside of the BBB. It will be useful in the future to evaluate the distribution of Aβ plaque labeling in various transgenic mice reported recently1,39,40. One important consideration is the total number of Aβ plaques on cerebral blood vessel walls, i.e. the Bmax for these new ligands. Because humans are physically larger and have an increased number of Aβ plaques on their cerebral blood vessel walls, it may be possible to efficiently detect such differences.

We prepared the desired ligands by stitching together multiple styrylpyridine cores (selective core for binding Aβ aggregates) using pegylation chains with chain lengths of n = 4, 5 and 6. It was assumed that Aβ aggregates composed of parallel β-sheets would likely contain repetitive and neighboring binding sites. These molecules were thus expected to show good binding to β-amyloid and to be excluded from the brain because of their large sizes.

Multidentate ligands have been utilized in various biological systems. Dimeric and multimeric ligands targeting αvβ3-integrin binding sites have been very useful for tumor imaging41–47. However, it is likely due to structural limitations of the parallel β-sheets of Aβ aggregates, as compared to that of the αvβ3-integrin binding sites, that the structure-activity-relationship for binding would be very different. In this report, we have prepared and examined the multidentate Aβ aggregate-binding affinity of 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10. Surprisingly, only the bidentate ligands 8a, 8b and 8c showed the desired high binding affinity comparable to that of [18F]5. The structural difference between the bidentate ligands 8a–c and 9 was the linkage for the pegylated styrylpyridines, i.e. ether vs. amide linkage, which may have caused the big difference in binding affinity (Ki = 3 – 7 nM vs. 71 nM). The binding affinity of the tri-dentate ligand, 10, also showed a dramatic reduction (Ki = 468 nM). This decrease may have been caused by changes in the geometry of the new ligand. These observations suggest that there are space limitations for multidentate ligands to insert themselves into β-amyloid and to bind to neighboring target sites.

The initial data from in vitro labeling of human brain sections also show that similar to [18F]5, [18F]8a is capable of labeling Aβ aggregates in human AD brain sections (Figure 4). It is important to note that the in vitro autoradiography of confirmed CAA brain sections showed successful labeling of major blood vessels by [18F]8a and the labeling was confirmed by co-staining with thioflavin S (Figure 5). The results strongly suggest that it will be feasible to use [18F]8a in imaging the accumulation of Aβ aggregates on the walls of major cerebral blood vessels in CAA patients. A buildup of Aβ aggregates in cerebral blood vessels also occurs in patients at risk of stroke and Alzheimer’s disease19. CAA discriminating Aβ imaging agents, due to the location of Aβ aggregates on the wall of cerebral blood vessels, may provide selective diagnostic tools that would be useful in teasing out the accumulation of Aβ aggregates in different areas, which can be associated with different clinical manifestations. Currently, it is assumed that the Aβ aggregates on the walls of major cerebral blood vessels in CAA are similar to those Aβ plaques in the brain (parenchymal). The new bidentate ligand, [18F]8a, will likely bind to Aβ aggregates on the blood vessels in a similar binding mechanism as it would bind to Aβ plaques in the brain. Further studies will be required to confirm that this assumption is true.

One other key factor for consideration is the number of binding sites associated with Aβ plaques on the blood vessels walls. These may not be as high as those reported for AD brain Kd = 3.72 ± 0.30 nM; Bmax = 8811 ± 1643 fmole/mg protein.22 However, the Aβ plaques located in the blood vessels may be more accessible and readily exposed to the CAA binding agent in the blood circulation. Therefore, the Aβ plaques in CAA may show higher apparent binding sites. This is a critical factor that warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

In summary, multi-dentate binding ligands targeting Aβ aggregates on cerebral vessels have been prepared and tested. They may provide useful tools for selective diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a significant risk factor in the older patient population.

Experimental

1. General

All reagents used for chemical synthesis were commercial products and were used without further purification. CD-1 mice (20 – 26 g) were used for the biodistribution studies. All protocols requiring the utilization of mice were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (University of Pennsylvania and University of the Sciences in Philadelphia). Postmortem human samples were obtained from phase III clinical trials of [18F]5. The synthesis of precursors and bidentate and tridentate styrylpyridine derivatives, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10, was accomplished by the following schemes (Scheme 1, 2, 3 and 4).

2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-1,3-di((E)-2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(methylamino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propane (8a)

A solution of 25a (0.0338 g, 0.031 mmol) in 0.9 mL trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 0.1 mL dimethyl sulfide was stirred at rt for 1 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH =92.5/7.5) to give 0.024 g yellowish oil 8a (yield: 87%) 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.14 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.76 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.35 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.86 (d, 4H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.77 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.60 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.65 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.49 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.41 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.78–3.97 (m, 6H), 3.63–3.74 (m, 25H), 3.55–3.59 (m, 4H), 2.88 (s, 6H). 13CNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 162.9, 149.3, 145.2, 135.3, 128.6, 127.8, 126.8, 120.7, 112.7, 111.5, 85.2, 81.8, 79.0, 71.82, 71.14, 70.9, 70.9, 70.8, 70.2, 70.0, 69.8, 65.5, 30.9. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C49H68FN4O11 (MH+), 907.4869; found, 907.4870.

2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-1,3-di((E)-2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(methylamino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propane (8b)

Compound 8b was prepared from 25b (0.0650 g, 0.054 mmol) in 0.5 mL TFA and 0.05 mL dimethyl sulfide, with the same procedure described for compound 8a. Compound 8b: 0.050 g (yield: 93%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.14 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.75 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.86 (d, 4H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.59 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.65 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 4.48 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.41 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 3.80–3.96 (m, 6H), 3.52–3.77 (m, 37H), 2.86 (s, 6H). 13CNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 162.8, 149.2, 145.2, 135.3, 128.5, 127.8, 126.7, 120.6, 112.7, 111.4, 85.1, 81.8, 78.9, 71.8, 71.1, 70.8, 70.7, 70.2, 70.0, 69.8, 65.4, 30.8. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C53H76FN4O13 (MH+), 995.5393; found, 995.5371.

2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-1,3-di((E)-2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(methylamino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propane (8c)

Compound 8c was prepared from 25c (0.0950 g, 0.074 mmol) in 0.9 mL TFA and 0.1 mL dimethyl sulfide, with the same procedure described for compound 8a. Compound 8c: 0.074 g (yield: 92%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.13 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.75 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.85 (d, 4H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.58 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.64 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 4.47 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.40 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.81–3.96 (m, 6H), 3.54–3.79 (m, 45H), 2.85 (s, 6H). 13CNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 162.7, 149.2, 145.1, 135.2, 128.5, 127.7, 126.6, 120.5, 112.6, 111.4, 85.1, 81.7, 78.8, 71.7, 71.0, 70.8, 70.2, 69.9, 69.8, 65.4, 30.0. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C57H84FN4O15 (M+H+), 1083.5917; found, 1083.5890.

2-(2-(2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N,N-bis(14-(5-((E)-4-(methylamino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)-2-oxo-6,9,12-trioxa-3-azatetradecyl)acetamide (9)

A solution of 34 (0.0400 g, 0.031 mmol) in 0.9 mL TFA and 0.1 mL dimethyl sulfide was stirred at rt for 1 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH =92.5/7.5) to give 0.021 g yellowish oil 8a (yield: 62%) 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.14 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.76 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.35 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.86 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.76 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 6.60 (d, 4H, 8.6 Hz), 4.68 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.42–4.51 (m, 5H), 4.17 (s, 2H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 3.97 (s, 2H), 3.79–3.88 (m, 6H), 3.54–3.70 (m, 28H). 3.43–3.50 (m, 4H), 2.87 (s, 6H). 13CNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 170.7, 169.3, 169.1, 162.7, 149.3, 145.2, 135.4, 128.6, 127.8, 126.7, 120.5, 112.7, 111.4, 85.0, 81.7, 70.9, 70.8, 70.6, 70.5, 70.0, 69.6, 65.4, 39.6, 30.9. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C56H79FN7O14 (M+H+), 1092.5669; found, 1092.5557.

1,3-Di(E)-(1-(2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(methylamino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methoxy-2-(((E)-(1-(2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(methylamino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methoxy)methyl)-2-((2-(2-(2-fluoroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)methyl)propane (10)

A solution of 39 (0.0900 mg, 0.046 mmol) in 0.6 mL TFA and 0.06 mL dimethyl sulfide was stirred at rt for 1 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH =95/5) to give 0.063 g yellowish oil 8a (yield: 82%) 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.12 (d, 3H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.69–7.76 (m, 6H), 7.33 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.84 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.73 (d, 3H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.58 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.64 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.38–4.58 (m, 19H), 3.75–3.88 (m, 13H), 3.42–3.72 (m, 41H), 2.84 (s, 9H). 13CNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 162.7, 149.2, 145.4, 145.1, 135.3, 128.5, 127.8, 126.7, 123.7, 120.4, 112.6, 111.3, 85.0, 81.6, 71.2, 71.0, 70.8, 70.8, 70.7, 70.5, 70.3, 69.9, 69.6, 69.5, 65.3, 65.2, 50.3, 45.6, 30.8. HRMS (ESI) calculated for C86H116FN15O18Na (M+Na+), 1688.8505; found, 1688.8490.

tert-Butyl 4-vinylphenylcarbamate (11)

To a solution of aminostyrene (1.19 g, 10 mmol) in 10 mL water (H2O) was added di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (Boc2O, 2.40 g, 11 mmol). After vigorously stirring at 35 °C for 4 h, the mixture was extracted with dichloromethane (DCM, 25 mL × 2). The organic layer was dried by anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (FC) (ethyl acetate (EtOAc) /hexane = 2/8) to give 2.18 g white solid 11 (yield: 99%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.34 (s, 4H), 6.67 (dd, 1H, J = 10.8 Hz, J = 17.6 Hz), 6.47 (br, 1H), 5.66 (d, 1H, J = 17.6 Hz), 5.17 (d, 1H, J = 11 Hz), 1.53 (s, 9H).

tert-Butyl methyl(4-vinylphenyl)carbamate (12)

To a suspension of NaH (60%, 0.600 g, 15 mmol) in 30 mL N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) was slowly added 11 (2.19 g, 10 mmol) in 20 mL DMF followed by iodomethane (CH3I, 7.10 g, 50 mmol). After stirring at room temperature (rt) for 6 h, the reaction mixture was quenched with 40 mL sat. ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) at 0 °C. The mixture was then extracted with 120 mL EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with H2O (40 mL × 2) as well as brine (40 mL), dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 2/8) to give 2.32 g white solid 12 (yield: 99%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.37 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.20 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.70 (dd, 1H, J = 11 Hz, J = 17.6 Hz), 5.72 (d, 1H, J = 17.6 Hz), 5.24 (d, 1H, J = 11 Hz), 3.26 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

2-(2-(2-(5-Iodopyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethanol (13a)

In a 20-mL Biotage microwave reaction vial, 2-Chloro-5-iodopyridine (2.39 g, 10 mmol), tetraethylene glycol (3.00 g, 20 mmol), cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 4.89 g, 15 mmol), and DMF (10 mL) were mixed and capped. After microwave heating at 150 °C for 55 min, the mixture was cooled to rt and diluted with 150 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (40 mL × 2) as well as brine (40 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 7/3) to give 2.37 g white solid 4 (yield: 67%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.31 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.79 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.65 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.45 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.85 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.60–3.76 (m, 8H).

2-(2-(2-(2-(5-Iodopyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethanol (13b)

Compound 13b was prepared from 2-Chloro-5-iodopyridine (3.59 g, 15 mmol), triethylene glycol (5.83 g, 30 mmol), Cs2CO3 (7.34 g, 22.5 mmol), and DMF (10 mL), with the same procedure described for compound 13a. Compound 13b: 3.27 g (yield: 55%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.31 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.78 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.64 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.45 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.85 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.60–3.74 (m, 12H).

(E)-tert-Butyl 4-(2-(6-(2-(2-(2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)vinyl)phenyl(methyl)carbamate (14a)

Compound 14a was prepared from 12 (2.33 g, 10 mmol), 13b (2.66 g, 6.7 mmol), K2CO3 (2.31 g, 16.75 mmol), tetrabutylammonium bromide (4.31 g, 13.4 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.0750 g, 0.34 mmol) and 50 mL DMF, with the same procedure described for compound 16. Compound 14a: 3.07 g (yield: 91%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.51 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.88 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.60–3.78 (m, 12H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.56 (t, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 1.47 (s, 9H).

(E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (15a)

To a solution of 14a (3.07 g, 6.1 mmol) and triethylamine (3.03 g, 30 mmol) in 30 mL DCM was added p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (2.29 g, 12 mmol) and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, 0.0732 g, 0.6 mmol) at 0 °C. The solution was allowed to warm to rt. After 50 min, the mixture was diluted with 80 mL DCM, washed with H2O (30 mL × 2) as well as brine (30 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and concentrated to give an oil that was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 1/1) to give 3.21 g white solid 15a (80%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.78–7.83 (m, 3H), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.24 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.17 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.86 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.63–3.72 (m, 10H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.45 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

(E)-14-(5-(4-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)-3,6,9,12-tetraoxatetradecyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (15b)

NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.08 g, 2 mmol) was placed in a two-neck flask and washed with hexane. 4 mL DMF was added to form a suspension. A solution of 16 (0.459 g, 1 mmol) in 3 mL DMF was added dropwise at 0 °C. After stirring at rt for 30 min, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and a solution of diethylene glycol di(p-toluenesulfonate) (1.24 g, 3 mmol) in 3 mL DMF was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was then poured into 10 mL cold 10% NaHCO3, and extracted with DCM (20 mL × 2). The organic layer was washed with H2O (10 mL × 2) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, concentrated and purified by FC (DCM/MeOH = 98/2) to give 0.470 g clear oil 15b (yield: 67%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.78–7.83 (m, 3H), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.24 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.17 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.7 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.59–3.76 (m, 14H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.45 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

(E)-17-(5-(4-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)-3,6,9,12,15-pentaoxaheptadecyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (15c)

Compound 15c was prepared from NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.120 g, 3 mmol), 14a (0.754 g, 1.5 mmol), diethylene glycol di(p-toluenesulfonate) (1.87 g, 4.5 mmol) and 15 mL DMF, with the same procedure described for compound 15b. Compound 15c: 0.759 g (yield: 68%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.78–7.83 (m, 3H), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.24 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.17 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.87 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.59–3.75 (m, 18H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.45 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

(E)-tert-Butyl 4-(2-(6-(2-(2-(2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)vinyl)phenyl(methyl)carbamate (16)

A mixture of 12 (0.710 g, 3.0 mmol), 13a (0.706g, 2.0 mmol), potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 0.690 g, 5.0 mmol), tetrabutylammonium bromide (1.29 g, 4.0 mmol), and palladium acetate (Pd(OAc)2, 0.0224 g, 0.10 mmol) in 15 mL DMF was deoxygenated by purging into nitrogen for 15 min and then heated at 65 °C for 2 h. The mixture was cooled to RT, diluted with 80 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (20 mL × 2) as well as brine (20 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 8/2) to give 0.753 g white solid 16 (yield: 82%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.52 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.89 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.61–3.80 (m, 8H), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.46 (t, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 1.47 (s, 9H).

2-(1,3-Dibromopropan-2-yloxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (17)

To a solution of 1,3-dibromopropane-2-ol (2.18 g, 10 mmol) in 20 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF) was added pyridinum p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS, 0.25 g, 1 mmol) and 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran (1.68 g, 20 mmol). After stirring at rt for 3 h, the mixture was diluted with 100 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (30 mL × 2) as well as brine (30 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 5/95) to give 2.72 g clear oil 17 (yield: 90%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.78–4.82 (m, 1H), 3.89–4.06 (m, 2H), 3.51–3.74 (m, 5H), 1.55–1.85 (m, 6H).

2-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propane-1,3-diyl diacetate (18)

A mixture of 17 (3.83 g, 12.6 mmol), tetrabutylammonium acetate (11.4 g, 37.8 mmol), tetrabutylammonium iodide (0.923 g, 2.5 mmol) and K2CO3 (0.345 g, 2.5 mmol) in 20 mL anhydrous acetonitrile was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was filtered and the filtrate was concentrated. The residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 5/95) to give 2.81 g clear oil 18 (yield: 86%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.79–4.81 (m, 1H), 4.03–4.31 (m, 5H), 3.88–3.97 (m, 1H), 3.49–3.57 (m, 1H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 1.55–1.84 (m, 6H).

2-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)propane-1,3-diol (19)

A mixture of 18 (1.30 g, 5 mmol) and 25 mL ammonia solution (2.0 M in methanol) was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was then concentrated in vacuo to afford 0.81 g yellow oil 19 (yield: 91%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.60–4.63 (m, 1H), 4.01–4.06 (m, 1H), 3.53–3.80 (m, 6H), 1.84–1.96 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.59 (m, 4H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (20a)

NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.160 g, 4 mmol) was placed in a two-neck flask and washed with hexane. 5 mL DMF was added to form a suspension. A solution of 19 (0.176 g, 1 mmol) in 5 mL DMF was added dropwise at 0 °C. After stirring at rt for 30 min, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and a solution of 15a (1.31 g, 2 mmol) in 3 mL DMF was added dropwise, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was then poured into 50 mL cold sat. NH4Cl, and extracted with DCM (50 mL × 2). The organic layer was washed with H2O (30 mL) and brine (30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, concentrated and purified by FC (EtOAc: 100%) to give 0.835 g clear oil 20a (yield: 73%). 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.73–4.82 (m, 1H), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.85–4.02 (m, 6H), 3.50–3.71 (m, 29H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.56–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (20b)

Compound 20b was prepared from NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.052 g, 1.3 mmol), 19 (0.0581 g, 0.33 mmol) and 15b (0.469 g, 0.67 mmol) in 8 mL DMF, with the same procedure described for compound 20a. Compound 20b: 0.310 g (yield: 76%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.79–4.81 (m, 1H), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.84–4.05 (m, 6H), 3.62–3.71 (m, 37H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.56–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (20c)

Compound 20c was prepared from NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.080 g, 2 mmol), 19 (0.0851 g, 0.48 mmol) and 15c (0.745 g, 1 mmol) in 10 mL DMF, with the same procedure described for compound 20a. Compound 20c: 0.522 g (yield: 82%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.79–4.81 (m, 1H), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.85–4.05 (m, 6H), 3.45–3.71 (m, 45H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.56–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-ol (21a)

A mixture of 20a (0.841 g, 0.73 mmol) and PPTS (0.0183 g, 0.073 mmol) in 7 mL EtOH was stirred at 55 °C for 3 h. The mixture was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/MeOH = 9/1) to give 0.732 g colorless oil 21a (yield: 94%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.84–4.05 (m, 6H), 3.45–3.80 (m, 28H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-ol (21b)

Compound 21b was prepared from 20b (0.295 g, 0.24 mmol) and PPTS (0.0060 g, 0.024 mmol) in 3 mL EtOH, with the same procedure described for compound 21a. Compound 21b: 0.177 g (yield: 62%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.48–4.52 (m, 4H), 3.84–4.05 (m, 6H), 3.45–3.80 (m, 36H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-ol (21c)

Compound 21b was prepared from 20c (0.524 g, 0.4 mmol) and PPTS (0.0100 g, 0.04 mmol) in 4 mL EtOH, with the same procedure described for compound 21a. Compound 21c: 0.340 g (yield: 69%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.84–4.05 (m, 6H), 3.45–3.80 (m, 44H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (22a)

NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.0552 g, 1.38 mmol) was placed in a two-neck flask and washed with hexane. 4 mL DMF was added to form a suspension. A solution of 21a (0.73 g, 0.69 mmol) in 3 mL DMF was added dropwise at 0 °C. After stirring at rt for 30 min, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and a solution of 2-(2-bromoethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (0.288 g, 1.38 mmol) in 3 mL DMF was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was then poured into 50 mL cold sat. NH4Cl, and extracted with DCM (30 mL × 2). The organic layer was washed with H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, concentrated and purified by FC (EtOAc/MeOH = 98/2) to give 0.574 g colorless oil 22a (yield: 70%). 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.62–4.65 (m, 1H), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.55–3.89 (m, 39H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.56–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (22b)

Compound 22b was prepared from NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.0180 g, 0.45 mmol), 21b (0.172 g, 0.15 mmol) and 2-(2-bromoethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (0.0627 g, 0.3 mmol) in 2.5 mL DMF, with the same procedure described for compound 22a. Compound 22b: 0.130 g (yield: 68%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1HNMR δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.62–4.65 (m, 1H), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.52–3.89 (m, 47H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.56–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (22c)

Compound 22c was prepared from NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.022 g, 0.55 mmol), 21c (0.333 g, 0.27 mmol) and 2-(2-bromoethoxy)-tetrahydro-2H-pyran (0.115 g, 0.55 mmol) in 4 mL DMF, with the same procedure described for compound 22a. Compound 22c: 0.310 g (yield: 83%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1HNMR δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.62–4.65 (m, 1H), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.57–3.89 (m, 55H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.56–1.96 (m, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethanol (23a)

A mixture of 22a (0.570 g, 0.48 mmol) and PPTS (0.0120 g, 0.048 mmol) in 6 mL EtOH was stirred at 55 °C for 6 h. The mixture was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/MeOH = 9/1) to give 0.477 g colorless oil 23a (yield: 90%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.18 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.79 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.96 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.49 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.86 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.64–3.79 (m, 29H), 3.49–3.58 (m, 4H), 3.27 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethanol (23b)

Compound 23b was prepared from 22b (0.128 g, 0.1 mmol) and PPTS (0.0025 g, 0.01 mmol) in 1 mL EtOH, with the same procedure described for compound 23a. Compound 23b: 0.116 g (yield: 98%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.6 Hz, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.87 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.65–3.79 (m, 37H), 3.51–3.55 (m, 4H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethanol (23c)

Compound 23c was prepared from 22c (0.314 g, 0.23 mmol) and PPTS (0.00577 g, 0.023 mmol) in 2 mL EtOH, with the same procedure described for compound 23a. Compound 23c: 0.235 g (yield: 80%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.87 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.64–3.71 (m, 45H), 3.51–3.55 (m, 4H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethyl-4-methylbenzene sulfonate (24a)

To a solution of 23a (0.395 g, 0.36 mmol) and triethylamine (0.180 g, 1.79 mmol) in 5 mL DCM was added p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (0.135 g, 0.71 mmol) and DMAP (0.0044 g, 0.036 mmol) at 0 °C. The solution was allowed to warm to rt. After 1 h, the mixture was diluted with 30 mL DCM, washed with H2O (10 mL × 2) as well as brine (10 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and concentrated to give an oil that was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH = 95/5) to give 0.444 g yellowish solid 24a (yield: 97%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.18 (d, 2H, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.77–7.82 (m, 4H), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.33 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.79 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.15 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.80–3.89 (m, 6H), 3.55–3.74 (m, 25H), 3.44–3.51 (m, 4H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 2.44 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethyl-4-methylbenzene sulfonate (24b)

Compound 24b was prepared from 23b (0.125 g, 0.11 mmol), triethylamine (0.0525 g, 0.5 mmol), p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (0.0400 g, 0.21 mmol) and DMAP (0.0012 g, 0.01 mmol) in 2 mL DCM, with the same procedure described for compound 24a. Compound 24b: 0.134 g (yield: 96%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.77–7.82 (m, 4H), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.79 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.14 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.80–3.89 (m, 6H), 3.60–3.74 (m, 33H), 3.46–3.51 (m, 4H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 2.44 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(1,3-Di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propan-2-yloxy)ethyl-4-methylbenzenesulfonate (24c)

Compound 24c was prepared from 23c (0.230 g, 0.18 mmol), triethylamine (0.0909 g, 0.9 mmol), p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (0.0686 g, 0.36 mmol) and DMAP (0.0022 g, 0.018 mmol) in 3 mL DCM, with the same procedure described for compound 24a. Compound 24c: 0.240 g (yield: 98%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.1 8 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.78–7.82 (m, 4H), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.34 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.2 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.79 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.14 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.80–3.89 (m, 6H), 3.46–3.75 (m, 41H), 3.44–3.51 (m, 4H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 2.45 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-1,3-di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy) propane (25a)

A mixture of 24a (0.126 g, 0.1 mmol) and tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF, 0.25 mL, 1.0 M in THF) in 1.5 mL THF was stirred at 70 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/MeOH = 9/1) to give 0.054 g colorless oil 25a (yield: 49%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.17 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.78 (dd, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.43 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.22 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.96 (s, 4H), 6.78 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.64 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.48 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.40 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.94 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 3.85 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.79 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 3.62–3.73 (m, 25H), 3.54–3.58 (m, 4H), 3.26 (s, 6H), 1.46 (s, 18H).

2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-1,3-di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propane (25b)

Compound 25b was prepared from 24b (0.100 g, 0.074 mmol), TBAF (0.15 mL, 1.0 M in THF) in 1 mL THF, with the same procedure described for compound 25a. Compound 25b: 0.0726 g (yield: 82%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.18 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.79 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.79 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.65 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.41 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.95 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 3.78–3.89 (m, 5H), 3.53–3.77 (m, 37H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

2-(2-Fluoroethoxy)-1,3-di((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)propane (25c)

Compound 25c was prepared from 24c (0.171 g, 0.12 mmol), TBAF (0.24 mL, 1.0 M in THF) in 2 mL THF, with the same procedure described for compound 25a. Compound 25c: 0.123 g (yield: 80%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 4H), 6.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.65 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.42 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.96 (t, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 3.78–3.89 (m, 5H), 3.53–3.77 (m, 45H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

Ethyl 2-(2-(2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)acetate (26)

To a solution of tetraethylene glycol (3.02 g, 20 mmol) and boron trifluoride–diethyl ether (0.1 mL) in 40 mL DCM was slowly added ethyl diazoacetate (1.14 g, 10 mmol) in 10 mL DCM at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h and then washed with H2O (10 mL × 2) as well as brine (10 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and concentrated to give 1.19 g clear oil 26 (yield: 50%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.16–4.28 (m, 4H), 3.60–3.76 (m, 12H), 2.43 (t, 1H, J = 6.2 Hz), 1.30 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz).

Ethyl 2-(2-(2-(2-bromoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)acetate (27)

To a solution of triphenylphosphine (2.16 g, 8.25 mmol) and N-bromosuccinimide (1.47 g, 8.25 mmol) in 30 mL DCM was slowly added 26 (1.30 g, 5.5 mmol) in 20 mL DCM at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h and then washed with H2O (10 mL × 2) and brine (10 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and concentrated to give 1.39 g yellow oil 27 (yield: 85%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.16–4.28 (m, 4H), 3.68–3.86 (m, 10H), 3.48 (t, 2H, J = 6.4 Hz), 1.29 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz).

2-(2-(2-(2-Bromoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)acetic acid (28)

A solution of 27 (1.39 g, 4.6 mmol) in 15 mL sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 1 M)/THF (v/v, 1/1) was stirred at rt for 2 h. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 0.9 mL) was then added to the mixture. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was taken up in DCM. The mixture was filtered and the filtrate was concentrated to give 0.810 g clear oil 28 (yield: 65%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.17 (s, 2H), 3.75–3.88 (m, 10H), 3.52 (t, 2H, J = 6.4 Hz).

tert-Butyl 14-bromo-3-(2-tert-butoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4-oxo-6,9,12-trioxa-3-azatetradecan-1-oate (29)

To a solution of 28 (0.810 g, 2.9 mmol) in 15 mL DMF was added di-tert-butyl iminodiacetate (0.711 g, 2.9 mmol), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (0.882 g, 5.22 mmol), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (1.0 g, 5.22 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.674 g, 5.22 mmol). After stirring at rt overnight, the mixture was poured into 100 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (30 mL × 2) and brine (30 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 1/1) to give 0.931 g clear oil 29 (yield: 64%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.24 (s, 2H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 4.05 (s, 2H), 3.64–3.86 (m, 10H), 3.48 (t, 2H, J = 6.4 Hz), 1.49 (s, 9H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

14-Bromo-3-(carboxymethyl)-4-oxo-6,9,12-trioxa-3-azatetradecan-1-oic acid (30)

A solution of 29 (0.157 g, 0.3 mmol) in 3 mL TFA/DCM (v/v, 1/1) was stirred at rt for 2 h. Removal of solvent gave clear oil. After several times of co-evaporation with methanol, 0.112 g 30 (yield: 97%) was given as a clear oil: 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.49 (s, 2H), 4.34 (s, 2H), 4.28 (s, 2H), 3.74–3.92 (m, 10H), 3.49 (t, 2H, J = 6.0 Hz).

(E)-tert-Butyl 4-(2-(6-(2-(2-(2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)vinyl)phenyl(methyl)carbamate (31)

Sodium azide (0.566 g, 8.7 mmol) was added to a solution of 15a (1.91 g, 2.9 mmol) in 20 mL DMF. After stirring at 60 °C for 3 h, the mixture was then poured into 100 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (30 mL × 2) as well as brine (30 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 1/1) to give 1.33 g white solid 31 (yield: 87%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.20 (d, 1H, J = 2.6 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.81 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.51 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.88 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.66–3.72 (m, 10H), 3.39 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.28 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

(E)-tert-Butyl 4-(2-(6-(2-(2-(2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)pyridin-3-yl)vinyl)phenyl(methyl)carbamate (32)

Triphenylphosphine (0.472 g, 1.8 mmol) was added to a solution of 31 (0.379 g, 0.72 mmol) in 12.6 mL THF. After stirring at rt for 2h, 1.4 mL H2O was added and the mixture was heated at 60 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH/NH4OH = 90/9/1) to give 0.360 g white solid 32 (yield: 100%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.81 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.98 (s, 2H), 6.81 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 4.50 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.88 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.67–3.72 (m, 8H), 3.56 (t, 2H, J = 5.2 Hz), 3.28 (s, 3H), 2.890 (t, 2H, J = 5.2 Hz), 1.47 (s, 9H).

2-(2-(2-(2-Bromoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N,N-bis(2-(((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)amino)-2-oxoethyl)acetamide (33)

To a solution of 30 (0.116 g, 0.3 mmol) in 6 mL DCM was added N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (0.247 g, 1.2 mmol), 32 (0.301 g, 0.6 mmol) and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (0.0073 g, 0.06 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt for 3 h and filtered with celite. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH/NH4OH = 95/5/0.5) to give 0.161 g clear oil 33 (yield: 40%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.19 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.80 (dd, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.45 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.23 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.97 (s, 4H), 6.79 (dd, 2H, J = 3.4 Hz, J = 8.8 Hz), 4.50 (t, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.18 (s, 2H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 3.97 (s, 2H), 3.78–3.86 (m, 6H), 3.58–3.70 (m, 28H), 3.44–3.50 (m, 6H), 3.28 (s, 6H), 1.47 (s, 18H).

N,N-Bis(2-(((E)-2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)amino)-2-oxoethyl)-2-(2-(2-(2-fluoroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)acetamide (34)

A mixture of 33 (0.100 g, 0.074 mmol) and TBAF (0.15 mL, 1.0 M in THF) in 1 mL THF was stirred at 70 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (DCM/MeOH/NH4OH = 95/5/0.5) to give 0.045 g clear oil 34 (yield: 47%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.17 (d, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.79 (dd, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.44 (d, 4H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.22 (d, 4H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.96 (s, 4H), 6.78 (dd, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.67 (t, 1H, J = 4.1 Hz), 4.41–4.51 (m, 5H), 4.17 (s, 2H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 3.97 (s, 2H), 3.50–3.88 (m, 34H), 3.43–3.48 (m, 4H), 3.27 (s, 6H), 1.46 (s, 18H).

3-(Prop-2-ynyloxy)-2,2-bis((prop-2-ynyloxy)methyl)propan-1-ol (35)

An aqueous solution of NaOH (40 wt%, 10 mL) was added to a solution of pentaerythritol (2.00 g, 14.7 mmol) in 15 mL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). The solution was stirred at rt for 30 min. Propargyl bromide (97%, 9.8 mL, 110 mmol) was then added and the solution was kept at rt for an additional 10 h. The reaction mixture was then poured into 150 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (50 mL × 2) as well as brine (50 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 1/4) to give 2.29 g yellowish oil 35 (yield: 62%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.13 (d, 6H, J = 2.4 Hz), 3.69 (d, 2H, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.56 (s, 6H), 2.43 (t, 3H, J = 2.4 Hz).

11,11-Bis((prop-2-ynyloxy)methyl)-3,6,9,13-tetraoxahexadec-15-ynyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (36)

NaH (60% in mineral oil, 0.120 g, 3.0 mmol) was placed in a two-neck flask and washed with hexane. 6 mL DMF was added to form a suspension. A solution of 35 (0.500 g, 2.0 mmol) in 4 mL DMF was added dropwise at 0 °C. After stirring at rt for 30 min, the mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and a solution of triethylene glycol di(p-toluenesulfonate) (1.38 g, 3.0 mmol) in 3 mL DMF was added dropwise. After stirred at rt overnight, the mixture was poured into 50 mL cold sat. NH4Cl, and extracted with DCM (30 mL × 2). The organic layer was washed with H2O (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, concentrated and purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 3/7) to give 0.501 g colorless oil 36 (yield: 47%). 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.81 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.35 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.11–4.20 (m, 8H), 3.71 (t, 2H, J = 4.8 Hz), 3.58–3.60 (m, 8H), 3.52 (s, 6H), 3.45 (s, 2H), 2.46 (s, 3H), 2.41 (t, 3H, J = 2.4 Hz).

1-Fluoro-11,11-bis((prop-2-ynyloxy)methyl)-3,6,9,13-tetraoxahexadec-15-yne (37)

A mixture of 36 (0.200 g, 0.37 mmol) and TBAF (1.12 mL, 1.0 M in THF) in 4 mL THF was stirred at 70 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/hexane = 3/7) to give 0.122 g clear oil 37 (yield: 86%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 4.69 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.46 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.13 (d, 6H, J = 2.4 Hz), 3.84 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 3.67–3.71 (m, 5H), 3.59–3.64 (m, 4H), 3.54 (s, 6H), 3.47 (s, 2H), 2.41 (t, 3H, J = 2.4 Hz).

2-(2-(2-(3- (E)-(1-(2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-Butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methoxy-2,2-bis((E)-(1-(2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methoxymethyl)propoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (38)

A solution of 36 (0.0313 g, 0.058 mmol), 31 (0.0923 g, 0.175 mmol), sodium ascorbate(0.0174 g, 0.088mmol) and copper sulfate (CuSO4, 0.0028 g, 0.0175 mmol) in 2 mL t-BuOH/H2O (v/v, 1/1) was stirred at rt for 4 h. The reaction mixture was then poured into 10 mL EtOAc and washed with H2O (3 mL × 2) and brine (3 mL). The organic layer was dried by Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated, and the residue was purified by FC (EtOAc/MeOH = 9/1) to give 0.110 g clear oil 38 (yield: 90%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 8.17 (d, 3H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.76–7.82 (m, 5H), 7.71 (s, 3H), 7.45 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.33 (d, 2H, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.23 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 6H), 6.77 (d, 3H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.46–4.59 (m, 18H), 4.11–4.16 (m, 2H), 3.83–3.90 (m, 12H), 3.61–3.71 (m, 26H), 3.38–3.56 (m, 16H), 3.28 (s, 9H), 2.43 (s, 3H), 1.47 (s, 27H).

1,3-Di(E)-(1-(2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methoxy-2-(((E)-(1-(2-(2-(2-(2-(5-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl(methyl)amino)styryl)pyridin-2-yloxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methoxy)methyl)-2-((2-(2-(2-fluoroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)methyl)propane (39)

Compound 39 was prepared from 37 (0.0486 g, 0.126 mmol), 31 (0.201 g, 0.38 mmol), sodium ascorbate(0.0376 g, 0.19mmol) and CuSO4 (0.0061 g, 0.038 mmol) in 4 mL t-BuOH/H2O (v/v, 1/1), with the same procedure described for compound 38. Compound 39: 0.208 g (yield: 84%): 1HNMR (200 MHz, CDCl3): 8.17 (d, 3H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.79 (dd, 3H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.71 (s, 3H), 7.45 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.23 (d, 6H, J = 8.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 6H), 6.77 (dd, 3H, J = 8.6 Hz), 4.65 (t, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.39–4.60 (m, 19H), 3.77–3.90 (m, 13H), 3.43–3.73 (m, 41H), 3.28 (s, 9H), 1.47 (s, 27H).

2. Radiosynthesis of [18F]8a–c

Preparation of [18F]8a–c was achieved by using a modified method reported previously (see Scheme 5)27. Briefly, the 18F-fluoride ions were trapped on an activated QMA anion exchange cartridge and eluted with 1 mL Kryptofix®222/K2CO3 acetonitrile/water solution (22 mg Kryptofix®222/1.8 mg K2CO3/0.84 mL ACN/0.16 mL water). The solution was azeotropically dried twice with acetonitrile at 110 °C under a stream of argon. Approximately 1 mg of O-tosylated precursor (24a–c) was dissolved in 1 mL DMSO and added to the anhydrous Kryptofix/K2CO3/[18F]fluoride. The reaction was heated for 10 minutes at 110 °C and allowed to cool at room temperature for 5 minutes. 1 mL of a 10% (~4 N) HCl solution was added and heated at 80 °C for 7 minutes. The reaction was cooled in an ice bath, neutralized with a NaOH solution and diluted with water to about 8 mL total volume. The mixture was pushed through an activated C4 mini column (Vydac® Bioselect 214SPE3000 Reversed-Phase C4), washed twice with 3 mL water and [18F]8a–c was eluted with 1 mL ethanol (decay corrected radiochemical yields were 29%, 29% and 30%, respectively; radiochemical purity was > 98%). To ensure an accurate detection of free fluoride, other impurities and the desired products, [18F]8a–c, two HPLC systems were employed: (a) Gemini C18 150 × 4.6 mm, acetonitrile/10 mM ammonium format buffer 8/2 and flow rate of 1 mL/min and (b) Gemini C18 250 × 4.6 mm with a solvent gradient at a flow rate of 1 mL/min according to the following: 0 – 2 minutes 100% 10 mM ammonium formate buffer; 2 – 5 minutes ammonium formate buffer 100% to 30%, ACN 0% to 70%; 5 – 10 minutes ammonium formate buffer 30% to 0%, ACN 70% to 100%, 10 – 15 minutes ammonium formate buffer 0% to 100%, 15 – 18 minutes 100% ammonium formate buffer.

3. In vitro autoradiography of AD brain sections

Frozen brains from confirmed CAA, AD and control subjects were cut into 20 µm sections. The sections were incubated with the 18F labeled tracer in 40% ethanol for 1 hour. The sections were then dipped in saturated Li2CO3 in 40% ethanol (2 min wash, twice) and washed with 40% ethanol (2 min wash, once) followed by rinsing with water for 30 seconds. After drying, the sections were exposed to Kodak Biomax MR film for 12 – 18 hours. After the film was developed, the images were digitized.

4. Thioflavin S staining

Brain sections were immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 1 hr, then treated with 0.05% KMnO4 and bleached in 0.2% K2S2O5/0.2% oxalic acid in order to quench autofluorescence. Quenched tissue sections were stained with 0.025% thioflavin S in 40% ethanol for 3 – 5 min. The sections were differentiated in 50% ethanol and viewed using a Nikon E800 Fluorescence microscope with a CCD digital camera.

5. In vivo biodistribution study in ICR mice

To test [18F]8a–c as PET imaging agents for cerebral amyloid angiopathy, we first tested the biodistribution of these tracers in normal ICR mice (20 – 25 grams). A group of 5 – 6 mice were used for each time point of the biodistribution studies. After the mice were put under anesthesia with isoflurane (2 – 3%), 0.15 mL saline solution containing 925 KBq (25 µCi) of the tracer was injected via the lateral tail vein. The mice were sacrificed at 2 and 30 minutes post-injection by cardiac excision while under isoflurane anesthesia. The organs of interest were removed, weighed and the radioactivity was counted with a gamma counter (Packard Cobra). The percent dose per gram was calculated by a comparison of the tissue activity counts to counts of 1% of the initial dose. The initial dose was measured by aliquots of the injected material diluted 100 times and measured at the same time (0.5 min/sample, 80% efficiency).

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

The chemical structures and binding affinities of imaging agents targeting Aβ plaques in the brain are listed. All of these agents are small, neutral molecules showing high binding affinity and the ability to penetrate intact blood-brain barrier in vivo (previously published values *22, **34).

Figure 2.

Multi-dentate (bidentate and tridentate) ligands, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9 and 10, based on styrylpyridine cores aiming at multiple binding sites within the repeated β-sheet structure are shown. These novel ligands are designed to bind to the Aβ aggregates via a divalent or a trivalent attachment (binding) sites.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants awarded from the National Institutes of Health (ROI-AG-022559, H.F.K., and R43AG032206, D.S.). Authors thank Dr. Carita Huang for editing and reviewing this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- APP

β-amyloid precursor protein

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PIB

Pittsburgh compound B

- SB-13

4-N-methylamino-4'-hydroxystilbene

- IMPY

6-[iodo-2-(4'-N,N-dimethylamino)-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine

- [18F]AV-1, BAY-94-9172

[18F]florbetaben f 18

- [18F]AV-45

[18F]florbetapir f 18

- [18F]FPIB, GE067

[18F]flutemetamol f 18

- [18F]AZD4694

2-(2-([18F]fluoro)-6-methylaminopyridin-3-yl)benzofuran-5-ol

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available:

Method for in vitro binding assay and HPLC profiles of final tested compounds are included in the supporting material. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Soontornniyomkij V, Choi C, Pomakian J, Vinters HV. High-definition characterization of cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Hum. Pathol. 2010;41:1601–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher M, French S, Ji P, Kim RC. Cerebral microbleeds in the elderly: a pathological analysis. Stroke. 2010;41:2782–2785. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordonnier C. Brain microbleeds: more evidence, but still a clinical dilemma. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:69–74. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328341f8c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altmann-Schneider I, Trompet S, de Craen AJ, van Es AC, Jukema JW, Stott DJ, Sattar N, Westendorp RG, van Buchem MA, van der Grond J. Cerebral microbleeds are predictive of mortality in the elderly. Stroke. 2011;42:638–644. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poels MM, Ikram MA, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Breteler MM, Vernooij MW. Incidence of cerebral microbleeds in the general population: the rotterdam scan study. Stroke. 2011;42:656–661. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dierksen GA, Skehan ME, Khan MA, Jeng J, Nandigam RN, Becker JA, Kumar A, Neal KL, Betensky RA, Frosch MP, Rosand J, Johnson KA, Viswanathan A, Salat DH, Greenberg SM. Spatial relation between microbleeds and amyloid deposits in amyloid angiopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2010;68:545–548. doi: 10.1002/ana.22099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weller RO, Boche D, Nicoll JA. Microvasculature changes and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease and their potential impact on therapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:87–102. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0498-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weller R, Preston S, Subash M, Carare R. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the aetiology and immunotherapy of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Research & Therapy. 2009;1:6. doi: 10.1186/alzrt6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. Alzheimer's disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1064-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attems J. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: pathology, clinical implications, and possible pathomechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attems J, Lintner F, Jellinger KA. Amyloid beta peptide 1–42 highly correlates with capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer disease pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;107:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jellinger KA, Attems J. Prevalence and pathogenic role of cerebrovascular lesions in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005:229–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.11.018. 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jack CR, Jr, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Zeng G, Bernstein MA, Gunter JL, Pankratz VS, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Knopman DS. Brain beta-amyloid measures and magnetic resonance imaging atrophy both predict time-to-progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2010;133:3336–3348. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinne J, Brooks D, Rossor M, Fox N, Bullock R, Klunk W, Mathis C, Blennow K, Barakos J, Okello A, Rodriguez Martinez de Liano S, Liu E, Koller M, Gregg K, Schenk D, Black R, Grundman M. 11C-PiB PET assessment of change in fibrillar amyloid-beta load in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with bapineuzumab: a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:363–372. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner M, Aisen P, Jack C, Jr, Jagust W, Trojanowski J, Shaw L, Saykin A, Morris J, Cairns N, Beckett L, Toga A, Green R, Walter S, Soares H, Snyder P, Siemers E, Potter W, Cole P, Schmidt M. The Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative: progress report and future plans. Alzheimers & Dementia. 2010;6:202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.007. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko S, Bi W, Paljug WR, Debnath ML, Hope CE, Isanski BA, Hamilton RL, Dekosky ST. Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiB-PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2008;131:1630–1645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mok V, Leung E, Chu W, Chen S, Wong A, Xiong Y, Lam W, Ho C, Wong K. Pittsburgh compound B binding in poststroke dementia. Journal of Neurological Science. 2010;290:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ly J, Donnan G, Villemagne V, Zavala J, Ma H, O'Keefe G, Gong S, Gunawan R, Saunder T, Ackerman U, Tochon-Danguy H, Churilov L, Phan T, Rowe C. 11C-PIB binding is increased in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related hemorrhage. Neurology. 2010;74:487–493. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cef7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, Kinnecom C, Salat DH, Moran EK, Smith EE, Rosand J, Rentz DM, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Dekosky ST, Fischman AJ, Greenberg SM. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2007;62:229–234. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong D, Rosenberg P, Zhou Y, Kumar A, Raymont V, Ravert H, Dannals R, Nandi A, Brasic J, Ye W, Hilton J, Lyketsos C, Kung H, Joshi A, Skovronsky D, Pontecorvo M. In Vivo Imaging of Amyloid Deposition in Alzheimer Disease Using the Radioligand 18F-AV-45 (Flobetapir F 18) J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51:913–920. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kung H, Choi S, Qu W, Zhang W, Skovronsky D. (18)F Stilbenes and Styrylpyridines for PET Imaging of Abeta Plaques in Alzheimer's Disease: A Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2009;53:933–941. doi: 10.1021/jm901039z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi S, Golding G, Zhuang Z, Zhang W, Lim N, Hefti F, Benedum T, Kilbourn M, Skovronsky D, Kung H. Preclinical properties of 18F-AV-45: a PET agent for Aβ plaques in the brain. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50:1887–1894. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Kung M, Oya S, Hou C, Kung H. (18)F-labeled styrylpyridines as PET agents for amyloid plaque imaging. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark CM, Schneider JA, Bedell BJ, Beach TG, Bilker WB, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Hefti F, Carpenter AP, Flitter ML, Krautkramer MJ, Kung HF, Coleman RE, Doraiswamy PM, Fleisher AS, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Reiman EP, Zehntner SP, Skovronsky DM. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA. 2011;305:275–283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Keefe G, Saunder T, Ng S, Ackerman U, Tochon-Danguy H, Chan J, Gong S, Dyrks T, Lindemann S, Holl G, Dinkelborg L, Villemagne V, Rowe C. Radiation Dosimetry of {beta}-Amyloid Tracers 11C-PiB and 18F-BAY94-9172. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50:309–315. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowe C, Ackerman U, Browne W, Mulligan R, Pike K, O'Keefe G, Tochon-Danguy H, Chan G, Berlangieri S, Jones G, Dickinson-Rowe K, Kung H, Zhang W, Kung M, Skovronsky D, Dyrks T, Holl G, Krause S, Friebe M, Lehman L, Lindemann S, Dinkelborg L, Masters C, Villemagne V. Imaging of amyloid beta in Alzheimer's disease with (18)F-BAY94-9172, a novel PET tracer: proof of mechanism. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:129–135. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Oya S, Kung M, Hou C, Maier D, Kung HH. F-18 Polyethyleneglycol stilbenes as PET imaging agents targeting Aβ aggregates in the brain. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2005;32:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, Oya S, Kung M, Hou C, Maier D, Kung H. F-18 Stilbenes as PET Imaging Agents for Detecting beta-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5980–5988. doi: 10.1021/jm050166g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koole M, Lewis D, Buckley C, Nelissen N, Vandenbulcke M, Brooks D, Vandenberghe R, Van Laere K. Whole-body biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 18F-GE067: a radioligand for in vivo brain amyloid imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50:818–822. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelissen N, Van Laere K, Thurfjell L, Owenius R, Vandenbulcke M, Koole M, Bormans G, Brooks DJ, Vandenberghe R. Phase 1 study of the Pittsburgh compound B derivative 18F-flutemetamol in healthy volunteers and patients with probable Alzheimer disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50:1251–1259. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas BA, Erlandsson K, Modat M, Thurfjell L, Vandenberghe R, Ourselin S, Hutton BF. The importance of appropriate partial volume correction for PET quantification in Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1104–1119. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vandenberghe R, Van Laere K, Ivanoiu A, Salmon E, Bastin C, Triau E, Hasselbalch S, Law I, Andersen A, Korner A, Minthon L, Garraux G, Nelissen N, Bormans G, Buckley C, Owenius R, Thurfjell L, Farrar G, Brooks D. (18)F-flutemetamol amyloid imaging in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: A phase 2 trial. Ann. Neurol. 2010;68:319–329. doi: 10.1002/ana.22068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]