Abstract

Functional dyspepsia is a group of disorders featuring symptoms believed to be derived from the stomach and duodenum such as upper abdominal discomfort, pain, postprandial fullness and early satiety. A key diagnostic requisite is the absence of organic, metabolic, or systemic disorders to explain "dyspeptic symptoms." Therefore, when peptic ulcer diseases (including scars), erosive esophagitis and upper gastrointestinal malignancies are found at endoscopic examinations, the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia is excluded. One notable exception, however, is Helicobacter pylori infection. According to the Rome III definition, H. pylori infection is included in functional dyspepsia. This is an obvious deviation from the diagnostic principle of functional dyspepsia, since H. pylori infection is a definite cause of mucosal inflammation, which affects a number of important gastric physiologies such as acid secretion, gastric endocrine function and motility. The chronic persistent nature of infection also results in more dramatic mucosal changes such as atrophy or intestinal metaplasia, the presence of which in the esophagus (Barrett's esophagus) precludes the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia. Since careful endoscopic examination can diagnose reliably H. pylori infection not only in Japan but also in Western contries, it is now feasible and more logical to exclude patients with chronic gastritis caused by H. pylori infection as having dyspeptic symptoms. It is time to establish the Asian consensus to declare that H. pylori infection should be separated from functional dyspepsia.

Keywords: Dyspepsia, Functional dyspepsia, Gastric acid, Helicobacter pylori, Ulcer

Introduction

Definition of functional dyspepsia (FD) has been revised in the past to better delineate the disorder, and most recently, internationally accepted definition is the so-called Rome III criteria proposed by the Rome III committees.1 In the documents, it was stated that "functional dyspepsia is defined as the presence of one or more dyspepsia symptoms that are considered to originate from the gastroduodenal region, in the absence of any organic, systemic or metabolic disease that is likely to explain the symptoms."1 They also propose 2 subgroups according to the symptoms: postprandial distress syndrome which includes bothersome postprandial fullness and/or early satiation as the main symptoms and epigastric pain syndrome that includes pain or burning localized to the epigastrium as the major symptom. However, heartburn, which had been included as a symptom of dyspepsia in the past, was excluded from symptom constellation of dyspepsia, although it may coexist with dyspeptic symptoms.

Current Rome III Definition for Functional Dyspepsia Is Not Satisfactory in Many Clinical Situations

How can you ascertain the absence of organic, systemic or metabolic diseases? They recommend the first diagnostic approach to exclude structural causes of dyspepsia presumed to be originating in the gastroduodenal region with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. By endoscopic examination, erosive reflux esophagitis, upper gastrointestinal malignancies and peptic ulcer diseases (including scars) can be identified and hence excluded with no need to consider whether the symptoms are truly caused by these organic diseases or not. Indeed, if you find peptic ulcer or early gastric cancer at the examination, how can you be certain that long-standing dyspeptic symptoms are actually caused by the organic diseases? There are a number of reports that almost half of the peptic ulcers were asymptomatic and the majority of early gastric cancers was asymptomatic.2,3 Nevertheless current criteria for excluding the diagnosis of FD do not require the proof that identified organic diseases are the actual cause of dyspeptic symptoms. For example, if a patient continues to complain of dyspeptic symptoms after complete healing of peptic ulcer diseases either by stopping non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or by eradicating Helicobacter pylori, should they be excluded as having functional dyspepsia? This issue has not been addressed by the Rome III definition.

On the other hand, higher rates of occurrence of peptic ulcer diseases (PUD) in H. pylori-positive patients diagnosed with "non-ulcer dyspepsia" or FD have been reported.4-7 Once they develop PUD, then would their diagnosis be changed from FD to PUD? If those H. pylori-positive patients with dyspepsia turn out to be categorized as having PUD, the published meta-analysis8 reporting the effects of eradication therapy would require re-evaluation by excluding those who developed PUD.

There also are grey-zones of defining organic diseases. For example, if you find a patient with erosive gastritis, will you defer the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia? According to review of the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the past clinical trials, there are notable inconsistencies on the inclusion of gastric erosions. When clinical trials of non-ulcer dyspepsia/functional dyspepsia to study the effect of eradication therapy that were selected for meta-analysis8 were compared, there was notable inconsistencies in the exclusion criteria (Table 1).9-18 Similarly, the exclusion criteria adopted in clinical trials for studying the effect of proton pump inhibitors are not uniform for gastric erosions (Table 2).19-25 In some trials, the number of erosions (such as over 5 erosions) was an exclusion criterion, but not others. In most of them, however, duodenal erosion was an exclusion criterion. To further complicate the matter, the distinction between erosion and ulcer is often arbitrarily defined in clinical trials examining the effects of anti-ulcer regimens for NSAIDs prevention; some use mucosal defect over 3 mm while others use 5 mm.26 Thus it might be possible that the "erosions" in these trails were defined as ulcer if mucosal defects were more than 3 mm. A recent meta-analysis,27 however, did not include gastroduodenal erosions as clinically significant findings without any legitimate explanation, although erosive esophagitis was considered as a significant finding.

Table 1.

Exclusion Criteria Reported in Trials Examining the Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy on Non-ulcer Dyspepsia/Functional Dyspepsia

O, included; X, excluded (including history and/or scar); △a, excluded if there are more than 5 erosions; △b, excluded if there are more than 10 erosions; N/D, not described.

Gastrointestinal malignancies were excluded in all the trials.

Table 2.

Exclusion Criteria Reported in Trials Examining the Effect of Proton Pump Inhibitors on Non-ulcer Dyspepsia/Functional Dyspepsia

O, included; X, excluded (including history and/or scar); △a, excluded if there are more than 5 erosions; △b, excluded if there are more than 10 erosions; N/D, not described.

Gastrointestinal malignancies were excluded in all the trials.

Gastric or duodenal erosions have structural changes easily identifiable by routine endoscopic examinations. As shown in the previous clinical trials, there were a number of inconsistencies for dealing with these conditions (Tables 1 and 2). From my point of view, it seems logical to exclude these obvious mucosal changes from functional diseases, although there is no conclusion how to handle these conditions based on solid evidence.

Helicobacter pylori Infection Is an Organic Disease

In the current Rome III definition, H. pylori infection is not an exclusion criterion of functional dyspepsia. This is an obvious deviation from the definition, because H. pylori infection causes definite microscopic and/or macroscopic changes in the gastric mucosa with its consequence on alterations in gastric physiologies. H. pylori strains predominant in the North Eastern Asia are more virulent than other parts of the world and together with life-style factors, frequently cause severe phenotypes such as atrophy, intestinal metaplasia leading to gastric cancer,28,29 These mucosal changes are obvious even with conventional endoscopic examinations. A unique type of gastritis due to H. pylori infection, so-called nodular gastritis (Fig. 1), is also easily detected by routine endoscopic examinations, and can be confirmed by dye-spray method.30,31 Importantly, patients with this particular form of gastritis have a high percentage of dyspeptic symptoms, which resolve with eradication therapy accompanied with disappearance of goose-flesh appearance.30,31 Another example is the enlarged fold gastritis with hypochlorhydria, although no specific symptom of this condition have been described.32 Functional as well as histological changes were reported to be restored by eradication therapy, indicating H. pylori infection is the cause of structural as well as functional changes seen in enlarged fold gastritis. More conspicuous macroscopic changes such as atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are frequently observed in Japan where more virulent strains are predominant.28,29 Indeed in a report from Japan, a number of other mucosal disorders was identified by routine examinations for dyspeptic patients.33 Thus, H. pylori infection causes definite structural changes, fulfilling the definition for organic disease in many patients in Japan. It may be argued, however, that in the majority of H. pylori infection in the West, the subtlety of mucosal changes may evade reliable diagnosis and hence preclude exclusion by routine endoscopic examination. However, it has been reported not only in Japan but also in Europe that with the use of high-resolution endoscopy coupled with magnification can identify infection status of H. pylori with high accuracy.34,35 Therefore, if trained adequately, it is now feasible to predict the presence of H. pylori infection by identifying the regular arrangement of collecting venules (so-called "RAC" pattern) during routine endoscopic examinations. Even when the gastric mucosa is judged "normal" with routine endoscopic examinations by inexperienced hands, the diagnosis of H. pylori infection can still be established with other modalities such as urea breath test or serology.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic features of nodular gastritis. Note diffuse whitish elevations on the distal gastric mucosa (A, white light), which can be further enhanced by flexible spectral imaging color enhancement mode of observation (B).

Irrespective of the macroscopic appearance, inflammatory cell infiltrates with elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines are demonstrated by histology and cytokine assays. How can we call such an inflammatory mucosa with obvious microscopic and/or macroscopic (endoscopic) changes as non-organic disorders?

H. pylori infection also causes profound alteration in gastric physiology. Acid secretion during H. pylori infection depends upon the spread of atrophy and the local inflammatory states, which may be determined by complex host-bacterial interactions and environmental factors.36 In a subset of H. pylori-infected patients with antral predominant gastritis without corpus atrophy, acid secretion might be higher than normal and can be a cause of dyspeptic symptoms.37,38 As demonstrated by a small but significant effect of proton pump inhibitors,39,40 alterations in acid secretion can be a cause of symptoms in a subset of patients with H. pylori infection. Conversely, when atrophy extends into the corpus mucosa, diminished acid secretion has been shown to protect reflux diseases and hence may suppress a component of reflux-like symptoms of dyspepsia.41

Moreover, H. pylori infection affects an important gastric endocrine function, such as ghrelin dynamics.42 Since ghrelin is important in the regulation of food intake as well as gastrointestinal motility, the alteration of ghrelin status in the stomach might be contributive to dyspeptic symptoms. Indeed, alteration of ghrelin levels in functional dyspepsia has been reported, though the pathophysiological significance remains to be elucidated.43 Both acid secretion and ghrelin status can be reversed to some extent by eradication therapy,44-46 and restoration of these physiological changes may explain the beneficial effect of eradication therapy on dyspeptic symptoms in H. pylori infection.

Gastric motility may be linked to H. pylori infection in a subset of patients as demonstrated in human studies,47,48 although no correlation between gastric emptying to eradication therapy was reported by others.49 Further investigations into detailed mechanisms to explore the changes in various regulatory factors such as ghrelin and/or inflammatory cytokines linking to observed improvement should be required.

Proposal for Conceptual Consistency

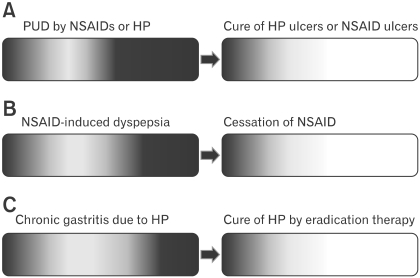

H. pylori is a pathogen invoking chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa associated with multiple alterations in gastric functions. Careful endoscopic examinations enable to identify mucosal changes caused by H. pylori infection. Therefore it will fit in a definite organic disease and should not be labeled as a functional disease. However, we might still see some patients having been cured of "organic diseases" remain dyspeptic. How can we reconcile such conflicting conditions? One idea is to specify the component of symptoms caused by organic diseases which should be resolved by a specific treatment. For example, if patients with dyspepsia who were recently prescribed NSAIDs were found to have PUD, they will be excluded from the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia. If patient who is negative for H. pylori infection has dyspeptic symptoms before taking NSAIDs and were negative for H. pylori infection and continues to complain similar symptoms after cessation of NSAIDs and cure of the ulcer, could you still regard the symptoms are due to PUD and preclude the diagnosis of FD? In such cases, residual or persistent symptoms of the patients might be better explained by accepting that they had overlapping functional dyspepsia. Similarly, patients with H. pylori infection should have specific symptoms ascribed to the infection, a typical example of which is nodular gastritis as described previously. Thus, effects of eradication may depend on the ratio of H. pylori infection contributing the symptoms of patients (Fig. 2). In this context, it might be plausible that eradication therapy showed greater symptomatic benefits in Asian trials50 where more virulent strains causing severe mucosal inflammation are prevalent,28,29 although direct link between the mucosal inflammation and symptoms still remains to be controversial.51,52

Figure 2.

Concept of coexistence of functional disorder with organic diseases. Dyspepstic subjects caused by specific organic causes are shown as graded dark area in the bar representing the population. Patients with severe symptoms are depicted darker in the right side of the bars. Unexplained persistent dyspeptic symptoms may be unraveled only after removal of the causative diseases or drugs. In peptic ulcer diseases (A), for example, a proportion of patients with dyspeptic symptoms may represnt the majority. In contrast, the proportion of symptomatic patients may be smaller in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug users (B) and in subjects with chronic gastritis (C). After curing the diseases or stopping the drugs responsible for the symptoms, some subjects may still continue to be symptomatic (indicated as a light grey part of the bars on the right side panels). This group of subjects may be considered as having functional dyspepsia. In this concept, organic diseases and functional diseases are not mutually exclusive and may coexist. PUD, peptic ulcer Diseases; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; HP, Helicobacter pylori.

The patients with H. pylori infection having dyspeptic symptoms should be treated first as H. pylori infection with dyspepsia instead of diagnosis then as functional dyspepsia having H. pylori infection because the spectrum of pathological as well as physiological changes caused by H. pylori infection clearly deserve to be included in organic diseases. The residual dyspeptic symptoms after complete cure of H. pylori infection may be considered to be caused by coexisting "functional dyspepsia," although complete resolution of submucosal inflammation after successful eradication was shown to require a prolonged period.53

In line with my proposal to separate the 2 entities, a similar naming (dyspepsia with H. pylori) was used in a recent proposal for the diagnostic algorithm of dyspepsia by a group of expert.54

Conclusion

In order to unravel pathophysiological mechanisms of FD and to establish more precise diagnostic markers or criteria, we should exclude organic diseases with distinct etiology such as H. pylori infection from an umbrella category of functional dyspepsia. Functional disorder should be considered only when residual symptoms persist despite of successful treatment targeted to cure the organic diseases.

Acknowledgements

The author greatly appreciate the encouragement and support by Professor Young-Tae Bak and Professor Nayoung Kim in writing this article.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. In: Drossman DA senior, editor. Rome III The functional gastrointestinal disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Virginia: Degnon Associates, Inc; 2006. pp. 420–425. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu CL, Chang SS, Wang SS, Chang FY, Lee SD. Silent peptic ulcer disease: frequency, factors leading to "silence," and implications regarding the pathogenesis of visceral symptoms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:34–38. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wand FW, Tu MS, Mar GY, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of asymptomatic peptic ulcer disease in Taiwan. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1199–1203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i9.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilvary J, Buckley MJ, Beattie S, Hamilton H, O'Morain CA. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori affects symptoms in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:535–540. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McColl K, Murray L, El-Omar E, et al. Symptomatic benefit from eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1869–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum AL, Talley NJ, O'Moráin C, et al. Lack of effect of treating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1875–1881. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Lo GH, et al. Risk factors for ulcer development in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia: a prospective two year follow up study of 209 patients. Gut. 2002;51:15–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moayyedi P, Decks J, Talley NJ, Delaney B, Forman D. An update of the Cochrane systematic review of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in nonulcer dyspepsia: resolving the discrepancy between systematic reviews. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2621–2626. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talley NJ, Janssens J, Lauritsen K, Rácz I, Bolling-Sternevald E. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia: randomized double blind placebo controlled trial with 12 months' follow up. BMJ. 1999;318:833–837. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7187.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talley NJ, Vakil N, Ballard ED, 2nd, Fennerty MB. Absence of benefit of eradicating Helicobacter pylori in patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1106–1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910073411502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miwa H, Hirai S, Nagahara A, et al. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection does not improve symptoms in non-ulcer dyspepsia patients-a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:317–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froehlich F, Gonvers JJ, Wietlisbach V, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment does not benefit patients with nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2329–2336. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koskenpato J, Farkkilä M, Sipponen P. Helicobacter pylori eradication and standardized 3-month omeprazole therapy in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2866–2872. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Tseng HH, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents ulcer development in patients with ulcer-like functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:195–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruley Des Varannes S, Fléjou JF, Colin R, Zaïm M, Meunier A, Bidaut-Mazel C. There are some benefits for eradicating Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1177–1185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malfertheiner P, MOssner J, Fischbach W, et al. Helicobacter eradication is beneficial in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:615–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koelz HR, Amold R, Stolte M, Fischer M, Blum AL FROSCH Study Group. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia resistant to conventional management: a double blind randomized trial with a six month follow up. Gut. 2003;52:40–46. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gisbert JP, Cruzado AI, Garcia-Gravalos R, Pajares JM. Lack of benefit of treating Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with functional dyspepsia. Randomized one-year follow-up study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:303–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley NJ, Meineche-Schmidt V, Paré P, et al. Efficacy of omeprazole in functional dyspepsia: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (the Bond and Opera studies) Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1055–1065. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farup PG, Hovde O, Trop R, Wetterhus S. Patients with functional dyspepsia resopinding to omeprazole have a characteristic gastro-oesophageal reflux pattern. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:575–579. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blum AL, Arnold R, Stolte M, Fischer M, Koelz HR. Short course acid suppressive treatment for patients with functional dyspepsia: results depend on Helicobacter pylori status. Gut. 2000;47:473–480. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolling-Sternevald E, Lauritsen K, Aalykke C, et al. Effect of profound acid suppression in functional dyspepsia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1395–1402. doi: 10.1080/003655202762671260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong WM, Wong BC, Hung WK, et al. Double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study of four weeks of lansoprazole for the treatment of functional dyspepsia in Chinese patients. Gut. 2002;51:502–506. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peura DA, Kovacs TO, Metz DC, Siepman N, Pilmer BL, Talley NJ. Lansoprazole in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116:740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Zanten SV, Armstrong D, Chiba N, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg once a day in patients with functional dyspepsia: the randomized placebo-controlled "ENTER" trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2096–2106. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeomans ND, Neasdal J. Systematic review: ulcer definition in NSAID ulcer prevention trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, Moayyedi P. What is the prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with dyspepsia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:830–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azuma T. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein variation associated withgastric cancer in Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaoka Y, Kato M, Asaka M. Geographic differences in gastric cancer incidence can be explained by differences between Helicoabacter strains. Inter Med. 2008;47:1077–1083. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Yoshihara M, et al. Nodular gastritis in adults is caused by Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:968–975. doi: 10.1023/a:1023016000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwivedi M, Misra SP, Misra V. Nodular gastritis in adults: clinical features, endoscopic appearance, histopathological features, and response to therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:943–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murayama Y, Miyagawa J, Shinomura Y, et al. Morphological and functional restoration of parietal cells in Helicobacter pylori associated enlarged fold gastritis after eradication. Gut. 1999;45:653–661. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimatani T, Inoue M, Iwamoto K, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, endoscopic gastric findings and dyspeptic symptoms among a young Japanese population born in the 1970s. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1352–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yagi K, Aruga Y, Nakamura A, Sekine A. Regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC): a characteristic endoscopic feature of Helicobacter pylori-negative stomach and its relationship with eophago-gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anagnostopoulos GK, Yao K, Kaye P, et al. High-resolution magnification endoscopy can reliably identigy normal gastric mucosa, Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis, and gastric atrophy. Endoscopy. 2007;39:202–207. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amieva MR, El-Omar E. Host-bacterial interactions in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:306–323. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurlimann N, Dür S, Schwab P, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori on gastritis, pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion, and mealstimulated plasma gastrin release in the absence of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1277–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.409_x.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McColl KE, el-Omar E, Gillen D. Interactions between H. pylori infection, gastric acid secretion and anti-secretory therapy. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:121–138. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, Forman D, Talley NJ. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329–1337. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, et al. Effects of proton-pump inhibitors on functional dyspepsia: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux esophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330–334. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osawa H, Nakazato M, Date Y, et al. Impaired production of gastric ghrelin in chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:10–16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogiso K, Asakawa A, Amitani H, Inui A. Ghrelin: a gut hormonal basis of motility and functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(suppl 3):67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iijima K, Ohara S, Sekine H, et al. Changes in gastric acid secretion assayed by endoscopic gastrin test before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gut. 2000;46:20–26. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osawa H, Kita H, Ohnishi H, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication induces marked increase in H+/K+-adenosine triphosphatase expression without altering parietal cell number in human gastric mucosa. Gut. 2006;55:152–157. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.066464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osawa H, Kita H, Ohnishi H, et al. Changes in plasma ghrelin levels, gastric ghrelin production, and body weight after Helicobacter pylori cure. J Gastoenterol. 2006;41:954–961. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyaji H, Azuma T, Ito S, et al. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on gastric antral myoelectrical activity and gastric emptying in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1303–1309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumoto Y, Ito M, Kamino D, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Relation between histologic gastritis and gastric motility in Japanese patients with functional dyspepsia: evaluation by transabdominal ultrasonography. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:332–337. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2172-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kachi M, Shirasaka D, Aoyama N, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on gastric emptying measured using the 13C-octanoic acid breath test and the acetaminophen method. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:824–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin X, Li YM. Systematic review and meta-analysis from Chinese literature: the association between Helicobacter pylori eradication and improvement of functional dyspepsia. Helicobacter. 2007;12:541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanghelini V, Barbara G, De Giorgio R, et al. Helicobacter pylori, mucosal inflammation and symptom perception-new insights into an old hypothesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(suppl 1):28–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turkkan E, Uslan I, Acarturuk G, et al. Does Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation of gastric mucosa determine the severity of symptoms in functional dyspepsia? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:66–70. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veijola L, Oksanen A, Linnala A, Sipponen P, Rautelin H. Persistent chronic gastritis and elevated Helicobacter pylori antibodies after successful eradication therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:605–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:757–763. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]