To the Editor

Since 1950s, studies have linked cigarette smoking to total and cause-specific mortalities. Few studies have comprehensively presented patterns of total and cause-specific mortality reduction upon smoking cessation,1, 2 or age at quitting3, comparing risks with both never and current smokers. We thus assessed the relationship of time since quitting and age at smoking cessation with total and cause-specific mortality of major non-communicable diseases among 19,705 US male physicians.

Methods

The methods of the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS), an institutional review board-approved trial of 22,071 physicians starting 1982-1984, on aspirin and β-carotene have been described previously.4 Detailed smoking information was collected from 20,148 men on their 60-month questionnaire. Death certificates were obtained for confirmation and review of cause of death. All mortality endpoints are adjudicated by the PHS Endpoints Committee. The main outcome was death between 3 years after the date of 60-month questionnaire return and March 9, 2010. A total of 19,705 eligible participants were included in the analysis.

We calculated “years since quitting” among past smokers by subtracting the age at quitting from the age at the date of 60-month questionnaire return. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate Hazard Ratios (HRs) for smoking status, years since quitting and age at quitting on total and/or cause-specific mortality. Person-years were accrued from the date of return of the 60-month questionnaire until either the date of death or the end of follow up. We adjusted baseline variables including aspirin and beta-carotene treatment, body mass index (<25, 25-30, ≥30 kg/m2), alcohol intake (less than daily, daily or more), vigorous exercise (<1, 1-4, ≥5 times/week), history of diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol, parental history of MI prior to age 60, age at started smoking and number of cigarette pack smoked per day. We assessed effect modification by age at started smoking (≥20 and <20 years) and smoking dose (≥1 vs <1 pack/day) on the association between years since quitting and total mortality. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Among the 19,705 male physicians, 41.7% were past and 6.7% were current smokers with mean age 58.3 years at the beginning of the follow-up. Past and current smokers had a similar average number of packs smoked per day and age starting smoking, but the average total years of smoking among current smokers was almost twice as long as that of past smokers. Comparing to never smokers, both current and past smokers had higher BMI, were more likely to consume alcohol daily and were more likely to have a history of hypertension or diabetes. Never and past smokers were more likely to vigorously exercise five or more times a week than current smokers.

A total of 5594 deaths occurred during the 386,772 person-years of follow-up. The crude mortality rates were 11.5, 16.6, and 26.1 per 1,000 person-years for never, past and current smokers. Among 612 deaths in current smokers, 13.7% died before the age of 65, as compared with 8.3% in never smokers. Current smokers had significantly higher risks of major cause-specific mortalities compared to never smokers, including all cardiovascular diseases and sudden death (HR, 3.42; 95% CI 2.26-5.20), pulmonary disease (HR, 8.27; 95% CI 5.76-11.86), lung cancer (HR, 16.43; 95% CI 11.28-23.93), smoking-related cancers including larynx, kidney, acute myeloid leukemia, oral cavity, esophageal, pancreatic, bladder and stomach cancer (HR, 2.74; 95% CI 1.97-3.83), colorectal cancer (HR, 3.59; 95% CI 2.25-5.71), and prostate cancer (HR, 1.79; 95% CI 1.14-2.81).

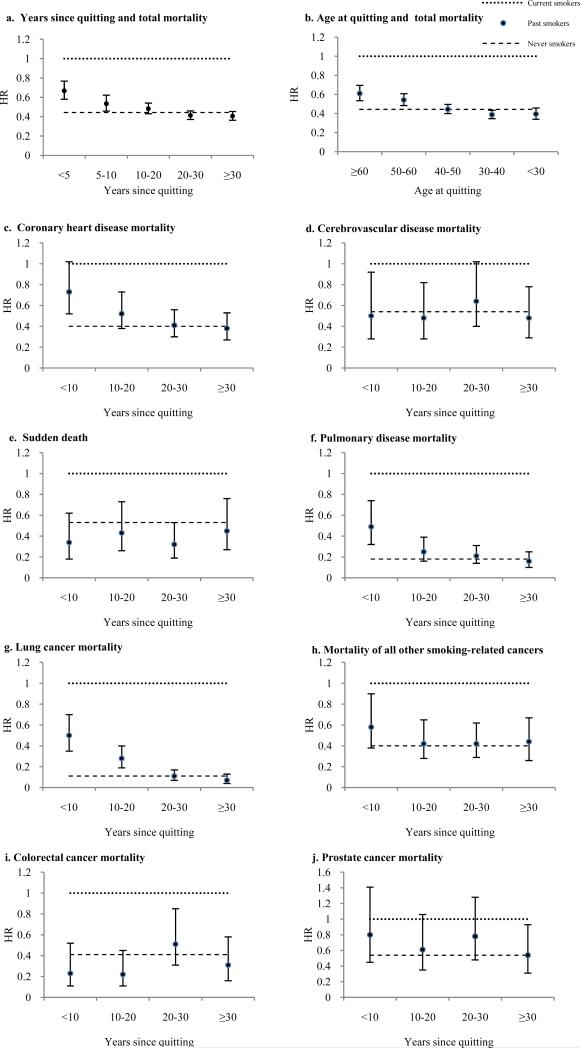

Compared with current smokers, the risk of dying was significantly reduced among past smokers within 10 years of quitting (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.54-0.68). By 20 years of quitting, the risk was further reduced (HR, 0.48; 95% CI 0.43-0.54) to the level of never smokers (HR, 0.44; 95% CI 0.40-0.50) (Figure a).

Figure. Time since quitting, age at quitting and total and cause-specific mortality.

Current smokers were the reference category, and the horizontal dashed line refers to hazard ratio in never smokers. The multivariate model was adjusted for baseline characteristics, including body-mass index, exercise, alcohol intake, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, history of high cholesterol, parental history of MI prior to 60 years, aspirin treatment, beta-carotene treatment, packs of cigarettes per day, age at started smoking, and age at 60-month questionnaire return. Smoking-related cancers include larynx, kidney, acute myeloid leukemia, oral cavity, esophageal, pancreatic, bladder and stomach cancer.

Compared with current smokers, quitting after age 50 or 60 years old significantly reduced risk of total mortality (HR,0.54; 95% CI 0.48-0.61 and HR, 0.61; 95% CI 0.54-0.70, respectively) among past smokers. However, only quitting before age 50 could completely eliminate the excess risk of mortality due to smoking (Figure b).

Pattern of total mortality reduction upon smoking cessation were similar in those who initiated smoking before and after 20 years of age. Although current heavy smokers (≥1 packs/day) had the highest risk of dying compared to current light and past smokers, it could be reduced by 44% within 10 years of quitting and to similar risk as never smokers after more than 20 years (vs 10 years for light smokers).

Among past smokers, the risks of dying were quickly reduced to the level of never smokers within 10 years of quitting for cerebrovascular disease, sudden death and colorectal cancer; after 10 years for smoking-related cancers other than lung cancer; after 20 years for coronary heart disease, pulmonary disease and lung cancer; and after 30 years of cessation for prostate cancer (Figure c-j).

Comment

Our findings in the US male physicians are consistent with the results from the US female nurses such that the risk of total mortality decreased to the level of never smokers 20 years after quitting.1, 2 Our analysis also conveyed a clear public health message on the benefit of quitting smoking at an early age, suggesting that even men who quit after age 60 had a 39% lower risk of death compared to those who continued to smoke. In addition, this study provided new evidence on the patterns of cause-specific mortality reduction upon smoking cessation, such as sudden death, colorectal cancer and prostate cancer.

Almost consistent but with an early decline compared with the US national trend, smoking prevalence peaked at 1960 (35.4 %) and decreased to 6.7% in 1988 in these US male physicians. The observed reduction in mortality as a result of smoking cessation could in part explain the national decline in total mortality, mortality of cardiovascular diseases,5 smoking-related cancers,6 and colorectal and prostate cancer.7 Our study reinforces the critical need for tobacco control, especially in countries where the smoking prevalence is high, to reduce the global burden of non-communicable diseases.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Physicians’ Health Study (PHS) is supported by grants CA42182, CA-34944, CA-40360, and CA-097193 from the National Cancer Institute and grants HL-26490 and HL-34595 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Ma had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Cao, Ma. Acquisition of data: Ma. Analysis and interpretation of data: Cao, Kenfield, Song, Rosner, Qiu, Sesso, Ma. Drafting of the manuscript: Cao. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cao, Kenfield, Song, Rosner, Qiu, Sesso, Gaziano, Ma. Statistical analysis: Cao. Obtained funding: Gaziano, Ma. Administrative, technical, or material support: Ma. Study supervision: Ma.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Gaziano reported that over the past 3 years he has received investigator-initiated research grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health and Amgen; has served as a consultant for and has received honoraria from Bayer. The other authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional Contributions: We thank the participants in the PHS for their outstanding commitment and cooperation and the entire PHS staff for their expert and assistance.

References

- 1.Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. Smoking cessation in relation to total mortality rates in women. A prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Nov 15;119(10):992–1000. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-10-199311150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to mortality in women. JAMA. 2008 May 7;299(17):2037–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1989 Jul 20;321(3):129–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Decline in deaths from heart disease and stroke--United States, 1900-1999. JAMA. 1999 Aug 25;282(8):724–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The 2004 United States Surgeon General's Report: The Health Consequences of Smoking. N S W Public Health Bull. 2004 May-Jun;15(5-6):107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010 Sep-Oct;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]