Abstract

Testicular protein kinase 1 (TESK1) is a serine/threonine kinase with a structure composed of a kinase domain related to those of LIM-kinases and a unique C-terminal proline-rich domain. Like LIM-kinases, TESK1 phosphorylated cofilin specifically at Ser-3, both in vitro and in vivo. When expressed in HeLa cells, TESK1 stimulated the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions. In contrast to LIM-kinases, the kinase activity of TESK1 was not enhanced by Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) or p21-activated kinase, indicating that TESK1 is not their downstream effector. Both the kinase activity of TESK1 and the level of cofilin phosphorylation increased by plating cells on fibronectin. Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of ROCK, inhibited LIM-kinase-induced cofilin phosphorylation but did not affect fibronectin-induced or TESK1-induced cofilin phosphorylation in HeLa cells. Expression of a kinase-negative TESK1 suppressed cofilin phosphorylation and formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions induced in cells plated on fibronectin. These results suggest that TESK1 functions downstream of integrins and plays a key role in integrin-mediated actin reorganization, presumably through phosphorylating and inactivating cofilin. We propose that TESK1 and LIM-kinases commonly phosphorylate cofilin but are regulated in different ways and play distinct roles in actin reorganization in living cells.

INTRODUCTION

Actin cytoskeletal reorganization plays important roles in many basic cell activities, including cell movement, adhesion, morphogenesis, and cytokinesis. Actin reorganization is often triggered in response to extracellular stimuli, such as binding of growth factors and chemoattractants to cell surface receptors and ECM proteins to integrin receptors. To better understand the mechanisms of stimulus-induced actin reorganization, it is important to elucidate the signaling pathways that transduce external stimuli to the machinery controlling the dynamics and organization of actin filaments.

Actin filament dynamics, which underlie the actin reorganization, are coordinately regulated by several types of actin-binding proteins (Chen et al., 2000). Among them, cofilin and its close relative, actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF), bind to actin monomers and filaments and have the potential to depolymerize and sever actin filaments; hence they seem to play an essential role in the rapid turnover of actin filaments (Moon and Drubin, 1995; Bamburg et al., 1999). The activity of cofilin is reversibly regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation at Ser-3, with the phosphorylated form being inactive (Agnew et al., 1995; Moriyama et al., 1996). Cofilin phosphorylation is stimulated by lysophosphatidic acid in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells (Maekawa et al., 1999), whereas it is down-regulated by thrombin in platelets, chemoattractants in neutrophils, and other stimuli (Moon and Drubin, 1995). We and other investigators provided evidence that LIM-kinase 1 (LIMK1) and LIM-kinase 2 (LIMK2) (Mizuno et al., 1994; Okano et al., 1995) phosphorylate cofilin specifically at Ser-3, both in vitro and in vivo, and regulate actin cytoskeletal reorganization by phosphorylating and inactivating cofilin (Arber et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998). LIM-kinases are activated in cultured cells by Rho family small GTPases, Rac, Rho, and Cdc42, albeit the activation is indirect (Arber et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998; Sumi et al., 1999). Furthermore, serine/threonine kinases, p21-activated kinase (PAK), and Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), which are downstream effectors of Rac and Rho, respectively, directly phosphorylate a threonine residue (Thr-508) within the activation loop in the kinase domain of LIMK1 and significantly enhance the kinase activity (Edwards et al., 1999; Maekawa et al., 1999; Ohashi et al., 2000; Amano et al., 2001). These observations suggest that both Rac-PAK and Rho-ROCK signaling pathways can activate LIM-kinases, an event that in turn induces phosphorylation and inactivation of cofilin. Considering the significant role of cofilin in actin filament dynamics and its predicted important functions in diverse cell activities, it is conceivable that protein kinases other than LIM-kinases are involved in cofilin phosphorylation and play roles in signaling pathways distinct from those of LIM-kinases.

Testicular protein kinase 1 (TESK1) is a protein kinase with a unique structure composed of an N-terminal protein kinase domain and a C-terminal proline-rich domain (Toshima et al., 1995). TESK1 was named after its higher expression in the testis (Toshima et al., 1995, 1998), but we recently found its expression in various tissues and cell lines, albeit at a relatively low level; hence we assumed that TESK1 has general cellular functions rather than a specific function in the testis (Toshima et al., 1999). The protein kinase domain of TESK1 is closely related to those of LIM-kinases, with ∼50% amino acid identity, although their overall domain structures do differ (Toshima et al., 1995). Phylogenetic analysis of the protein kinase domains further revealed that TESK1 and LIM-kinases constitute a novel subfamily within a serine/threonine kinase family (Toshima et al., 1995). These observations led to the notion that TESK1 can phosphorylate cofilin/ADF family proteins and that it plays a role in the actin reorganization, as do LIM-kinases.

We now provide evidence that TESK1 phosphorylates cofilin and stimulates the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions. In contrast to LIM-kinases, the kinase activity of TESK1 is not stimulated by either ROCK or PAK but can be stimulated by plating cells on a fibronectin-coated surface. We propose that TESK1 has a role in integrin-mediated actin cytoskeletal reorganization through the phosphorylation of cofilin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction

Expression plasmids coding for rat TESK1, TESK1(D170A), and C-terminally Myc epitope-tagged human LIMK2 in pUC-SRα vector and human LIMK1 in pUcD2-SRα vector were constructed, as described (Okano et al., 1995; Toshima et al., 1999; Ohashi et al., 2000). Expression plasmids coding for Myc epitope-tagged human ROCKΔ3 and ROCK(KD-IA) in pCAG vector were constructed, as described (Ishizaki et al., 1997). Expression plasmid coding for N-terminally Myc epitope-tagged TESK1 was constructed by inserting an NcoI–NotI fragment of rat TESK1 cDNA (nucleotides 1129–3600) into the NotI site of pCAG-Myc-stop vector containing the Myc epitope sequence (EQKLISEEDL) and three frame stop codons (Ishizaki et al., 1997). Expression plasmids coding for Myc-tagged PAKΔN were constructed by inserting PCR-amplified human PAK3 fragment (corresponding to amino acid residues 161–544) into NotI site of pCAG-Myc-stop vector (Frost et al., 1998). Expression plasmid (pEGFP-C1) coding for green fluorescence protein (GFP) was purchased from Clontech (Cambridge, UK). Expression plasmid coding for C3 exoenzyme was constructed into pEF-BOS vector. Expression plasmids coding for N-terminally hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (YPYDVPDYAGSRS)-tagged mouse cofilin and its S3A mutant, and plasmids for C-terminally Sky-peptide (QQGLLPHSSC)-tagged human ADF and its S3A mutant, were constructed by inserting PCR-amplified cofilin and ADF cDNAs into the BglII site of pcDL-SRα vector (Moriyama et al., 1996; Yang et al., 1998). The authenticity of plasmids was verified by nucleotide sequencing with a 373A DNA sequencer (PE Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan).

Antibodies

An antibody specific to Ser-3-phosphorylated cofilin (P-cofilin) was prepared by immunizing rabbits with keyhole lympet hemocyanin conjugated with the phosphopeptide acetyl-A(pS)GVAVSDC, which was synthesized by Dr. S. Aimoto (Osaka University). The antiserum was purified by the antigenic peptide-conjugated column. Anticofilin monoclonal antibody MAB-22 was provided from Dr. T. Obinata (Chiba University) (Abe et al., 1989). Rabbit anti-TESK1 antibody (TK-C21) was raised against the C-terminal peptide of rat TESK1, as described (Toshima et al., 1998). Rabbit anti-LIMK1 antibody (C-10) was raised against the C-terminal peptide of human LIMK1, as described (Okano et al., 1995). They were purified by antigenic peptide-conjugated columns, as described (Toshima et al., 1995). Rabbit anti-Sky antibody was prepared, as described (Ohashi et al., 1995). Anti-Myc epitope monoclonal antibody (9E10) and anti-HA epitope monoclonal antibody (12CA5) were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Tokyo, Japan). Anti-His-tag polyclonal antibody and anti-vinculin monoclonal antibody (hVIN-1) were purchased from MBL (Nagoya, Japan) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO), respectively. To determine the specificity of anti-P-cofilin antibody, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was performed, as described (Agnew et al., 1995). C-terminally (His)6-tagged cofilin and ADF were expressed in COS-7 cells, purified with Ni-NTA agarose, incubated for 60 min at 37°C with 40 U of calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM MgCl2, and then subjected to in vitro kinase reaction with TESK1.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HeLa and COS-7 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. These cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. For transfection, 5 × 105 cells were grown in 100-mm culture dishes and transfected with 15 μg of plasmid DNA/100-mm dish, following the modified calcium phosphate method (Chen and Okayama, 1987) or Lipofectamine (Life Technologies-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) method. HeLa cells stably expressing TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) (HeLa/TESK1 or HeLa/TESK1[DA] cells) were isolated by transfection with pUcD2-SRα plasmids coding for TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) and selection with 400 μg/ml G418 (Sigma).

Cell Staining

Cells were plated on 24-mm glass coverslips and transfected with the plasmid DNA by the Lipofectamine (Life Technologies-BRL) method. After 24 h, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate buffer (80 mM K2HPO4, 20 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) for 15 min and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum. After blocking with PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum for 30 min, cells were incubated with a primary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS containing 2% fetal calf serum for 15 min, cells were incubated with a fluorescein-isothiocyanate–labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or rhodamine-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody (Chemicon) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were also stained for F-actin with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were photographed on a DMLB fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, suspended in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin), and incubated on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation, lysates were precleared with Protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan) (20 μl of 50% slurry) for 2 h at 4°C. The precleared supernatants were incubated with anti-TESK1 antibody (TK-C21), anti-LIMK1 antibody (C-10) or 9E10 anti-Myc monoclonal antibody, and Protein A-Sepharose (20 μl of 50% slurry) overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation, the immunoprecipitates were washed three times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) and used for in vitro kinase reaction and immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot Analysis

For immunoblot analysis, cell lysates or immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membrane was blocked overnight with 4% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with anti-TESK1 antibody (TK-C21), anti-LIMK1 antibody (C-10), anti-P-cofilin antibody, or 9E10 anti-Myc epitope antibody diluted in PBS containing 1% nonfat dry milk and 0.05% Tween 20. After washing in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or sheep anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Immunoreactive protein bands were visualized by exposing the membrane for 10 s to 2 min to an ECL chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with kinase reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 5 mM MnCl2, 5 mM MgCl2) and incubated for 30 min at 30°C in 40 μl of kinase reaction buffer containing 10 μM ATP and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in the presence of 50 μg/ml (His)6-tagged cofilin, ADF, or their S3A mutants. (His)6-tagged cofilin, ADF, and their mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified, as described (Moriyama et al., 1996). The reaction mixture was solubilized in Laemmli's sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1% SDS, 0.002% bromophenol blue) for 5 min at 95°C, and aliquots were separated on SDS-PAGE, using 15 and 9% gels. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). The membrane from a 15% gel was analyzed by autoradiography to measure 32P-labeled cofilin or ADF, using the BAS1800 Bio-Image Analyzer (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) and Amido-black staining. The membrane from the 9% gel was analyzed by immunoblotting with 9E10 anti-Myc antibody or anti-TESK1 antibody.

In Vivo Kinase Assay

In vivo kinase assay was performed using HA-tagged cofilin or ADF, as described (Yang et al., 1998). COS-7 cells were cotransfected with plasmid coding for HA-tagged cofilin, ADF, or S3A-cofilin, and plasmid for TESK1. Cells were labeled in DMEM containing 500 μCi/ml [32P]phosphoric acid for 4 h, washed three times with ice-cold PBS, and suspended in RIPA buffer. After incubation on ice for 1 h, lysates were precleared with Protein A-Sepharose (20 μl of 50% slurry) for 3 h at 4°C. The precleared supernatants were incubated with 12CA5 anti-HA-tag antibody (Roche Diagnostics) and Protein A-Sepharose (20 μl of 50% slurry) overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation, the immunoprecipitates were washed three times with wash buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE in 15 and 9% gels. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membrane from a 15% gel was analyzed by autoradiography to measure 32P-labeled cofilin or ADF, using the BAS1800 Bio-Image Analyzer (Fuji Film) and immunoblotting with 12CA5 anti-HA or anti-Sky-peptide antibody. The membrane from 9% gel was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-TESK1 antibody.

Adhesion and Spreading Assay

For cell adhesion assay, 35- or 100-mm culture dishes were coated overnight at 37°C with 20 μg/ml fibronectin (purchased from Sigma) or 50 μg/ml poly-l-lysine (Sigma) in TBS buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (Fraction V, Sigma) in TBS buffer before cells are plated. HeLa cells (3 × 106 cells) cultured for 24 h in serum-free DMEM were trypsinized, suspended in 5 ml DMEM, then plated on fibronectin- or poly-l-lysine–coated and bovine serum albumin-blocked 100-mm dishes. After incubation for 0–60 min at 37°C, adherent cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer. Endogenous TESK1 and LIMK1 were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, using anti-TESK1 (TK-C21) or anti-LIMK1 antibody (C-10), and immunoprecipitates were subjected to in vitro kinase reaction. To determine the level of P-cofilin, cells were lysed with hot SDS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.5, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol) at 95°C for 5 min and sonicated. After centrifugation, supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-cofilin antibody. For cell staining, HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids coding for TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) and cultured for 24 h in serum-free DMEM. Approximately 2 × 105 cells were trypsinized, suspended in 1 ml DMEM, and then replated on fibronectin-coated 35-mm dishes. After incubation for 90 min at 37°C, cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate buffer, and costained with TK-C21 anti-TESK1 antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin or anti-vinculin antibody.

RESULTS

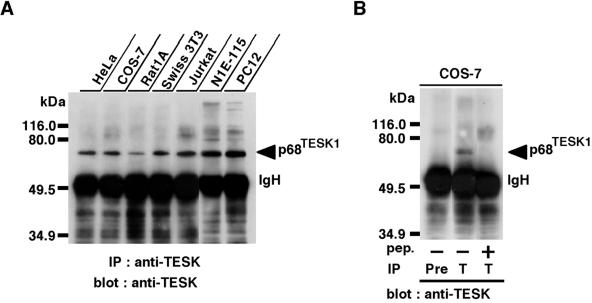

Expression of TESK1 Protein in Various Cell Lines

We previously showed the expression of TESK1 mRNA in various tissues and cell lines, although the level of expression is lower than that in the testis (Toshima et al., 1999). To examine the expression of TESK1 protein in cell lines, lysates from various cell lines were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis, using TK-C21 anti-TESK1 antibody. In our previous studies, we could not detect the expression of endogenous TESK1 protein in COS-7 cell lysates, under conditions in which we used lysates from 5 × 105 COS-7 cells (Toshima et al., 1995, 1999). In this study, we therefore used 10 times more cell lysates (5 × 106 cells), and the immunoblot membrane was exposed eightfold longer (2 min) to the ECL detection reagent, compared with the conditions used in the previous studies. As shown in Figure 1A, the one major immunoreactive band migrating at ∼68 kDa, similar to the calculated mass for TESK1 protein, was detected in various cell lines, including COS-7 cells, HeLa epithelial carcinoma cells, Rat1A and Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts, Jurkat T cell leukemia, N1E-115 neuroblastoma, and PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. This band was not detected when COS-7 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with preimmune serum or with anti-TESK1 antibody preincubated with antigenic peptide (Figure 1B), which suggests that the 68-kDa band represents the endogenously expressed TESK1 protein. The wide expression of TESK1 mRNA and protein in various tissues and cell lines suggests general cellular functions of TESK1.

Figure 1.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of endogenous TESK1 protein expressed in various cell lines. Lysates prepared from approximately 5 × 106 cells of each cell line were immunoprecipitated with anti-TESK1 antibody (TK-C21), run on SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with the same antibody. To detect endogenous TESK1 protein, the immunoblot membrane was exposed for 2 min in an ECL detection system. (B) Cell lysates of COS-7 cells were immunoprecipitated with an immunoglobulin G fraction of preimmune serum (Pre) or anti-TESK1 antibody (T) and immunoblotted with anti-TESK1 antibody. In the third lane, anti-TESK1 antibody was preincubated with excess amounts of antigenic C21 peptide. Positions of molecular size markers are indicated on the left. IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain; IP, immunoprecipitation.

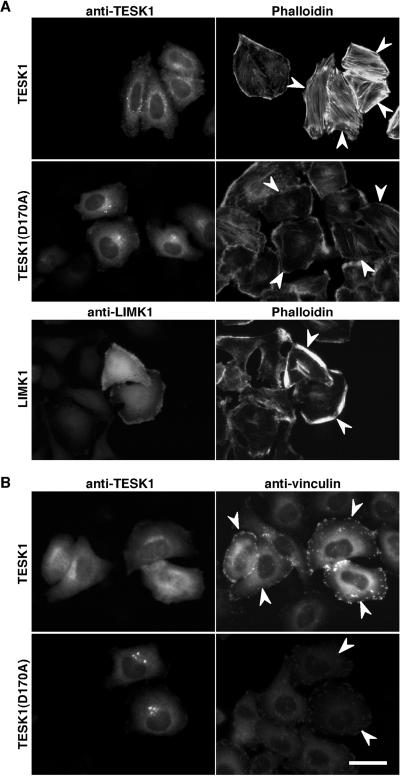

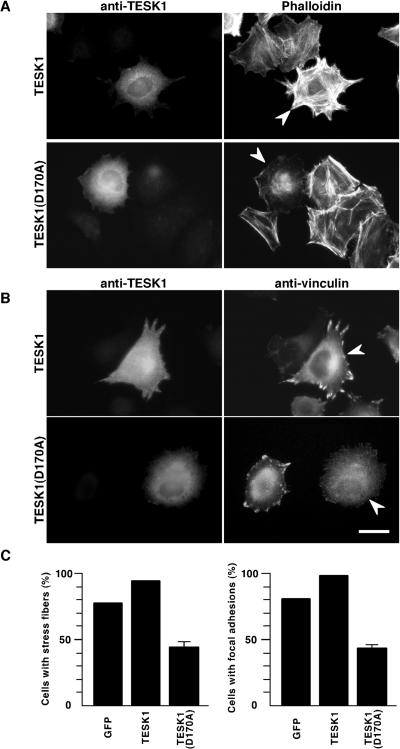

TESK1 Induces the Formation of Stress Fibers and Focal Adhesions

LIM-kinases induce actin reorganization in cultured cells. Because the kinase domain of TESK1 is similar to those of LIM-kinases, we asked whether TESK1 can induce changes in actin organization. When HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids coding for TESK1 and then stained with rhodamine-phalloidin to visualize actin filaments, marked induction of actin stress fibers was observed in TESK1-transfected cells, compared with findings with TESK1-nontransfected cells (Figure 2A, top panels). In contrast, expression of a kinase-inactive mutant of TESK1, TESK1(D170A), in which the presumptive catalytic residue Asp-170 is replaced by alanine, failed to induce stress fibers and seemed to partially reduce naturally occurring stress fibers (Figure 2A, middle panels). These results suggest that TESK1 can induce the formation of actin stress fibers, the function of which depends on its kinase catalytic activity. As reported (Yang et al., 1998), expression of LIMK1 induced the actin reorganization in HeLa cells, but the morphology of polymerized actin structures induced by LIMK1 was distinct from that induced by TESK1; in most of the LIMK1-expressing cells, actin filaments accumulated in the cell periphery (Figure 2A, bottom panels). Thus, TESK1 seems to play a role distinct from that of LIMK1 in actin reorganization. In addition, we observed that both TESK1 and its kinase-inactive mutant expressed in HeLa cells were localized diffusely in the cytoplasm, with dense staining at the perinuclear region; the pattern was distinct from that of LIMK1, which was enriched in the region of polymerized actin at the cell periphery (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Stress fibers and focal adhesions induced by TESK1. (A) Actin organization induced by TESK1 and LIMK1. HeLa cells transfected with plasmids encoding TESK1, TESK1(D170A), or LIMK1 were stained with anti-TESK1 or anti-LIMK1 antibody (left) and rhodamine-labeled phalloidin for F-actin (right). (B) Focal adhesions induced by TESK1. HeLa cells transfected with plasmids encoding TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) were stained with anti-TESK1 (left) and anti-vinculin antibody (right). Arrowheads indicate cells expressing TESK1, TESK1(D170A), or LIMK1. Bar, 15 μm.

The formation of stress fibers is usually accompanied by assembly of focal adhesions at cell margins. To determine whether TESK1 would induce focal adhesions, we transfected the TESK1 plasmid into HeLa cells, and the formation of focal adhesions was visualized by immunostaining vinculin, a major component of focal adhesions. Expression of TESK1 significantly induced the formation of focal adhesions, because vinculin staining was specifically enhanced at the margins of TESK1-expressing cells (Figure 2B, top panels). In contrast, expression of a kinase-inactive TESK1(D170A) failed to induce focal adhesions (Figure 2B, bottom panels). These findings suggest that TESK1 plays a role in the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions, both of which depend on its protein kinase activity.

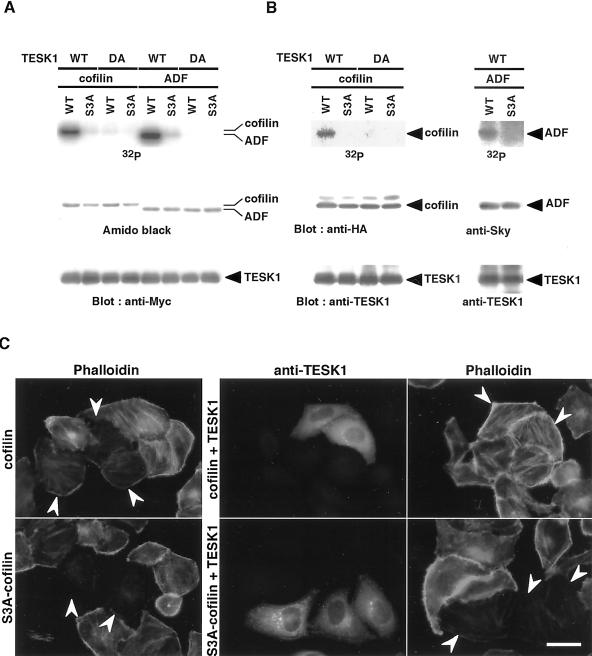

TESK1 Phosphorylates Cofilin and ADF In Vitro and In Vivo

To elucidate the mechanism by which TESK1 induces stress fibers and focal adhesions, we searched for the kinase substrate(s) for TESK1. Structural similarity of the kinase domains of TESK1 and LIM-kinases suggests that the cellular substrate(s) of these kinases may be similar or even identical. Because LIM-kinases phosphorylate cofilin specifically at Ser-3, the site of its inactivation, we examined whether TESK1 could phosphorylate cofilin in vitro and in vivo. Wild-type TESK1 and its kinase-inactive D170A mutant were expressed in COS-7 cells, immunoprecipitated, and subjected to in vitro kinase reaction, using recombinant (His)6-tagged cofilin as a substrate. As shown in Figure 3A, wild-type TESK1 phosphorylated wild-type cofilin, but not S3A-cofilin, in which Ser-3 is replaced by alanine. TESK1(D170A) did not phosphorylate either one. These results suggest that TESK1 phosphorylates cofilin specifically at Ser-3 in vitro. We also examined the kinase activity of TESK1 toward ADF, a protein closely related to cofilin. TESK1 phosphorylated ADF to an extent similar to that seen with cofilin, but not its S3A mutant (Figure 3A). Accordingly, TESK1 phosphorylates both cofilin and ADF specifically at Ser-3.

Figure 3.

In vitro and in vivo phosphorylation of cofilin and ADF by TESK1. (A) In vitro kinase assay. (His)6-tagged wild-type (WT) cofilin, ADF, or their S3A mutants were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP and Myc-tagged wild-type (WT) TESK1 or its D170A mutant (DA) prepared from COS-7 cells, separated on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed using autoradiography, Amido-black staining, and immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody. (B) In vivo kinase assay. Plasmids coding for either HA-tagged cofilin (WT), its S3A mutant, Sky-tagged ADF (WT), or its S3A mutant were cotransfected into COS-7 cells with plasmids for either TESK1 (WT) or TESK1(D170A) (DA). Cells were labeled with [32P]phosphoric acid, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA, anti-Sky, or anti-TESK1 antibody, run on SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by autoradiography and immunoblotting, as indicated. (C) TESK1 inhibits actin binding/depolymerizing activity of cofilin but not of S3A-cofilin in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids coding for HA-tagged cofilin or S3A-cofilin, with or without plasmids for TESK1. Cells were stained with anti-HA and anti-TESK1 antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin. Arrowheads indicate cells expressing cofilin (top panels) or S3A-cofilin (bottom panels), as assigned by immunostaining with anti-HA antibody. Bar, 15 μm.

We next asked whether TESK1 could phosphorylate cofilin and ADF in cultured cells. HA-tagged cofilin or its S3A mutant was expressed with wild-type or the kinase-inactive form of TESK1 in COS-7 cells, and then the cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate. 32P-incorporation into cofilin was evident when coexpressed with wild-type TESK1 but not with TESK1(D170A) (Figure 3B, left panel). 32P-incorporation into S3A-cofilin was nil by coexpression with either TESK1 or TESK1(D170A). In a similar manner, we observed 32P-incorporation into wild-type ADF but not into its S3A mutant, when they were coexpressed with TESK1 (Figure 3B, right panel). Thus TESK1 can phosphorylate cofilin and ADF specifically at Ser-3 in vivo as well as in vitro.

Cofilin and S3A-cofilin, when expressed in HeLa cells, induced marked decrease in rhodamine-phalloidin staining, which was caused by the actin-binding and -depolymerizing activity of cofilin (Figure 3C, left panels). When TESK1 was coexpressed with cofilin, the decrease in phalloidin staining induced by cofilin was reversed, and phalloidin staining of actin filaments was observed (Figure 3C, top right panel). In contrast, the decrease in phalloidin staining induced by nonphosphorylatable S3A-cofilin was not affected by coexpression with TESK1 (Figure 3C, bottom-right panels). Coexpression with a kinase-inactive TESK1(D170A) did not reverse the cofilin-induced loss of phalloidin staining (our unpublished results). These results further support the idea that TESK1, like LIM-kinases, can phosphorylate cofilin at Ser-3 and thereby inhibit the actin binding/depolymerizing activity of cofilin in cultured cells.

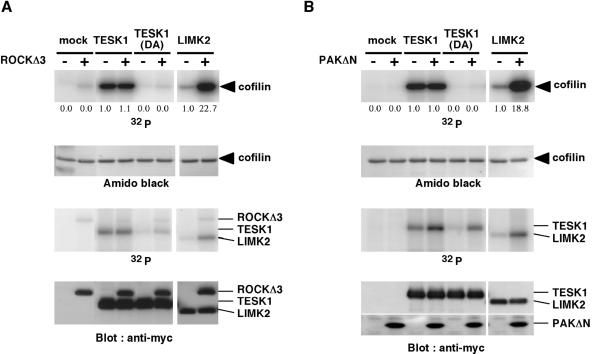

Effects of ROCK and PAK on the Kinase Activity of TESK1

Rho and Rac regulate actin reorganization: Rho induces actin stress fibers and focal adhesions, whereas Rac induces lamellipodia (Narumiya et al., 1997; Hall, 1998). ROCK and PAK, downstream effectors of Rho and Rac, respectively, directly phosphorylate and activate LIM-kinases. Because TESK1 induces stress fibers and focal adhesions, this kinase may act as a downstream effector of Rho and ROCK. We therefore tested the effect of Rho-ROCK pathway activation on the kinase activity of TESK1. When TESK1 was coexpressed in COS-7 cells with either an active form of Rho (RhoV14) or an active form of ROCK (ROCKΔ3), no increase in the kinase activity of TESK1 was observed (our unpublished results). This finding is in contrast to cases of LIM-kinases, the kinase activities of which were increased by coexpression with ROCKΔ3 or RhoV14 (Maekawa et al., 1999; Sumi et al., 1999; Ohashi et al., 2000; Amano et al., 2001). The kinase activity of TESK1 was not affected when it was coexpressed with an active form of Rac (RacV12) or Cdc42 (Cdc42V12) (our unpublished results). In addition, expression of a kinase-inactive mutant TESK1(D170A) had no apparent effect on RhoV14- or ROCKΔ3-induced stress fiber formation or RacV12-induced lamellipodium formation (our unpublished results). In vitro kinase reaction further revealed that the kinase activity of TESK1 was not affected by treatment with either ROCKΔ3 or an active form of PAK (PAKΔN), whereas the kinase activity of LIMK2 was significantly enhanced by ROCKΔ3 or PAKΔN (Figure 4). It is noted that TESK1 and TESK1(D170A) were evidently phosphorylated by PAKΔN (Figure 4B, third panel), but the physiological meaning of this phosphorylation remains to be determined. Taken together, these results suggest that in contrast to LIM-kinases, TESK1 is not a downstream effector of either ROCK or PAK.

Figure 4.

ROCK and PAK activate LIMK but not TESK1. Lysates from COS-7 cells transfected with vector alone (mock) or plasmids for Myc-tagged TESK1, TESK1(D170A), or LIMK2 were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and incubated with [γ-32P]ATP and (His)6-cofilin in the absence (−) or presence (+) of Myc-tagged ROCKΔ3 (A) or PAKΔN (B). Reaction mixtures were run on SDS-PAGE on 9 and 15% gels. In both A and B, the 15% gel was analyzed by autoradiography (top panel) and Amido-black staining for cofilin (second panel). The 9% gel was analyzed by autoradiography to detect phosphorylation of TESK1 and LIMK2 (third panel) and by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody (bottom panel). 32P-incorporation into TESK1 is due to autophosphorylation. Relative kinase activities of TESK1 and LIMK2 treated with or without ROCKΔ3 or PAKΔN are indicated under the top panel, with the activity of wild-type TESK1 and LIMK2 without ROCKΔ3 or PAKΔN taken as 1.0, respectively.

Effects of Rho-ROCK Signaling on TESK1-induced Stress Fiber and Focal Adhesion Formation

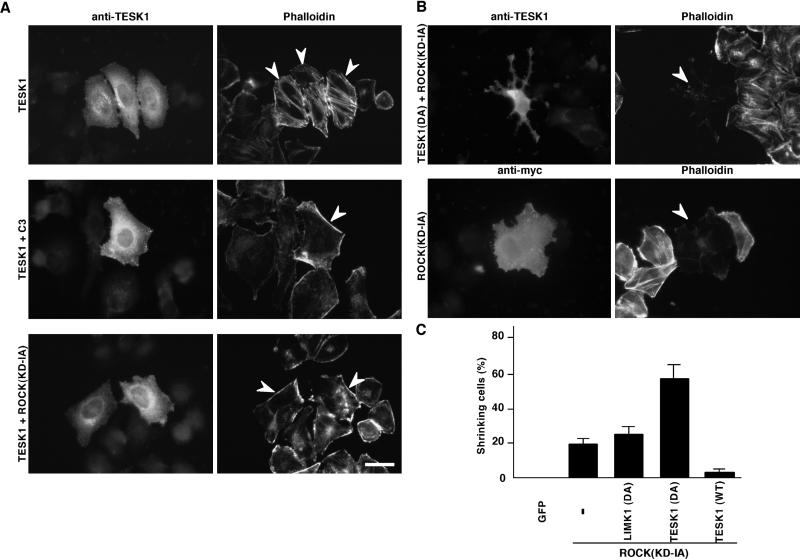

To further investigate the relationship between the Rho-ROCK signaling and TESK1-induced actin stress fibers, we examined the effects of Rho-ROCK inhibitors on TESK1-induced stress fibers. As shown in Figure 5A, TESK1-induced stress fibers were repressed by coexpression with C3 exoenzyme, a botulinum toxin that specifically inactivates Rho by ADP-ribosylation (Sekine et al., 1989), or ROCK(KD-IA), a dominant-negative mutant of ROCK (Ishizaki et al., 1997). Focal adhesions induced by TESK1 were also repressed by coexpression with C3 or ROCK(KD-IA) (our unpublished results). Thus, TESK1, albeit not a direct target of ROCK, does require activity of the Rho-ROCK signaling pathway for the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions.

Figure 5.

(A) Suppression of TESK1-induced stress fibers by C3 or ROCK(KD-IA). HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids for TESK1 with vector alone or plasmids for C3 or ROCK(KD-IA) and stained with anti-TESK1 antibody (left panels) and rhodamine-phalloidin (right panels). Arrowheads indicate the cells expressing TESK1. Bar, 15 μm. (B) Cell shrinkage induced by coexpression of ROCK(KD-IA) and TESK1(D170A). HeLa cells were cotransfected with plasmids for ROCK(KD-IA) with TESK1(D170A) (top panels) or vector (bottom panels) and stained with anti-TESK1 or anti-Myc antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin. Bar, 15 μm. (C) Quantification of the ratio of shrinking cells in ROCK(KD-IA)-expressing cells, when cotransfected with vector (−), plasmids for LIMK1(D460A), TESK1(D170A), or wild-type (WT) TESK1. GFP indicates cells expressing control GFP alone. The results of three experiments are shown as means ± SEM.

In addition, we also found that coexpression of ROCK(KD-IA) with TESK1(D170A) in HeLa cells induced an almost complete loss of actin filaments and remarkable changes in cell morphology (cell shrinkage leaving process-like structures) (Figure 5B). Although ROCK(KD-IA) alone also induced such shrinking phenotype in 20% of the transfected cells, coexpression with TESK1(D170A) significantly augmented the ratio of shrinking cells to 58% (Figure 5C). On the other hand, coexpression of a kinase-inactive mutant of LIMK1, LIMK1(D460A), had no apparent effect, which further suggests that LIMK1, but not TESK1, acts as a downstream effector of ROCK and that LIMK1 and TESK1 play distinct roles in the organization of actin filaments and cell morphology. Coexpression of wild-type TESK1 with ROCK(KD-IA) reduced the ratio of shrinking cells. These results suggest that both TESK1 and ROCK have an important role in maintaining normal cell morphology and adhesion by supporting the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions.

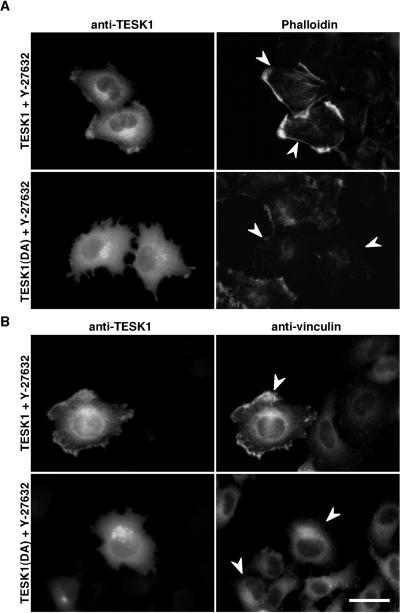

We next investigated the effects of Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of ROCK (Uehata et al., 1997), on TESK1-induced actin reorganization, to determine the short-term effects of ROCK inhibition. As reported (Uehata et al., 1997), stress fibers induced by RhoV14 were suppressed by a 30 min treatment of cells with Y-27632. Similarly, stress fibers in TESK1-transfected cells were reduced by treatment with Y-27632, but interestingly most of the TESK1-expressing cells showed polymerized actin structures and vinculin assemblies at cell peripheries (Figure 6, A and B). In TESK1(D170A)-expressing cells, no such structure but rather a significant loss of actin filaments was observed (Figure 6A). TESK1 was enriched in the region of polymerized actin structures at cell peripheries in the presence of Y-27632 (Figure 6A). Costaining with anti-TESK1 and anti-vinculin antibodies further revealed colocalization of TESK1 with vinculin at peripheries of Y-27632–treated cells (Figure 6B). Thus, under conditions that ROCK signaling was temporarily blocked by Y-27632, TESK1 induced polymerized actin structures and vinculin assemblies that are distinct from stress fibers and focal adhesions, at the cell periphery. Together with findings that ROCK does not activate TESK1, these observations suggest that TESK1 has a potential to induce actin reorganization independently on ROCK.

Figure 6.

Effect of Y-27632 on TESK1-induced actin organization. HeLa cells transfected with plasmids encoding TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) were treated with 10 μM Y-27632 for 30 min, then fixed and stained with anti-TESK1 antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin (A) or anti-vinculin antibody (B). Arrowheads indicate cells expressing TESK1 or TESK1(D170A). Bar, 15 μm.

Activation of Endogenous TESK1 by Integrin Signaling

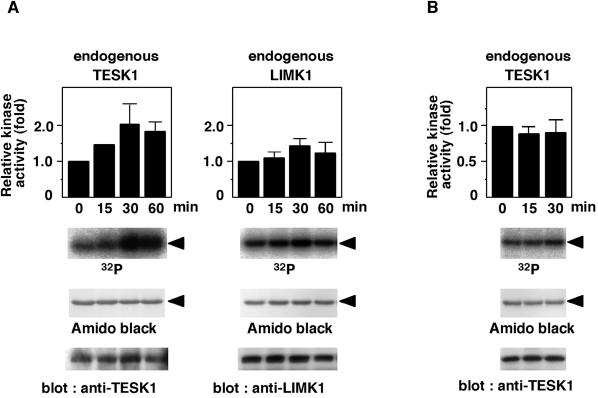

During cell adhesion and spreading on the fibronectin-coated surface, actin stress fibers and focal adhesions are induced by signaling mediated by integrin receptors (Clark and Brugge, 1995). Because TESK1 can induce assembly of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions, it may play a role in integrin signaling. We therefore examined changes in kinase activity of endogenous TESK1 during adhesion and spreading of HeLa cells on fibronectin. Suspended cells were plated onto fibronectin-coated dishes and cultured under the serum-free conditions. At indicated times, endogenous TESK1 was prepared by immunoprecipitation, and its kinase activity was measured in vitro, using recombinant cofilin as a substrate. The kinase activity of TESK1 gradually increased with time, reaching a maximum level at 30 min after plating (Figure 7A). A longer plating on fibronectin did not further promote the activity of TESK1. When we examined the kinase activity of endogenous LIMK1 in HeLa cells under similar conditions, only a small increase in LIMK1 activity was observed during cell spreading (Figure 7A). The activity of TESK1 was not stimulated when the cells were plated on a surface coated with poly-l-lysine (Figure 7B). These results suggest that the kinase activity of TESK1 is up-regulated by fibronectin-induced stimulation of integrin signaling pathways.

Figure 7.

Adhesion to fibronectin increases the kinase activity of TESK1. (A) HeLa cells were suspended and replated on fibronectin-coated dishes. At indicated times, cells were lysed, and endogenous TESK1 and LIMK1 were immunoprecipitated and subjected to in vitro kinase reaction, using (His)6-cofilin as a substrate. Reaction mixtures were run on SDS-PAGE and analyzed using autoradiography and Amido-black staining. Arrowheads indicate the position of cofilin. TESK1 and LIMK1 were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-TESK1 and anti-LIMK1 antibodies. Relative kinase activities of TESK1 and LIMK1 are shown as means ± SEM of triplicate experiments, with the activity of TESK1 and LIMK1 at zero time of plating taken as 1.0. (B) HeLa cells were plated on poly-l-lysine–coated dishes, and the kinase activity of TESK1 was analyzed as in A.

Increase in the Level of Cofilin Phosphorylation by Integrin Signaling

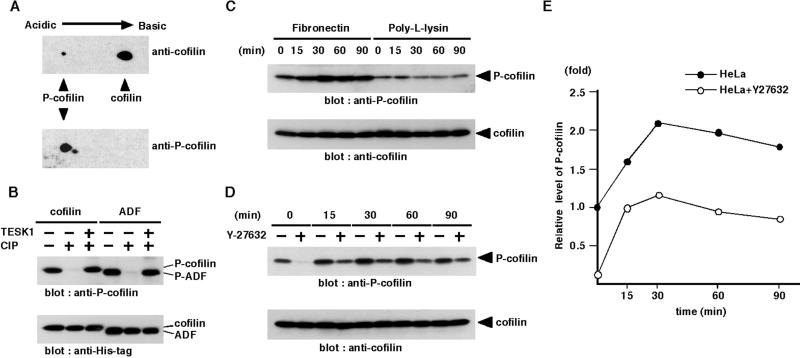

To determine the level of cofilin phosphorylation after plating cells on fibronectin, we prepared the antibody that specifically recognized the phosphorylated form of cofilin (P-cofilin). The specificity of the antibody was determined by immunoblot analysis of a two-dimensional gel of COS-7 cell lysates. The antibody reacted with P-cofilin (and also the phosphorylated form of ADF as a minor spot) but not with the dephosphorylated form of cofilin (Figure 8A). On one-dimensional gels of lysates of COS-7 cells transfected with plasmids for C-terminally (His)6-tagged cofilin and ADF, immunoreactive bands with the sizes corresponding to (His)6-tagged cofilin and ADF were detected with anti-P-cofilin antibody, but they disappeared during CIP treatment and recovered during rephosphorylation reaction with TESK1 (Figure 8B). These results suggest that the anti-P-cofilin antibody specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of cofilin and ADF.

Figure 8.

Adhesion to fibronectin increases the level of phosphorylated form of cofilin. (A) Specificity of anti-P-cofilin antibody. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of lysates of COS-7 cells was immunoblotted with anti-P-cofilin and anti-cofilin antibody. (B) The C-terminally (His)6-tagged cofilin and ADF were expressed in COS-7 cells and purified with Ni-NTA agarose. They were run directly on SDS-PAGE (lanes 1 and 4), after treatment with CIP phosphatase (lanes 2 and 5) or after CIP treatment followed by kinase reaction with TESK1 (lanes 3 and 6), and then immunoblotted with anti-P-cofilin and anti-His-tag antibody. (C) HeLa cells were suspended and replated on fibronectin- or poly-l-lysine–coated dishes. At indicated times, cells were lysed and the lysates were run on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-cofilin and anti-cofilin antibody. (D) HeLa cells were suspended, incubated for 30 min with or without 10 μM Y-27632, and replated on fibronectin-coated dishes. At indicated times, cells were lysed, and the level of P-cofilin was analyzed as in C. (E) Relative amounts of P-cofilin in HeLa cells treated with or without Y-27632 were plotted against the time after plating cells on fibronectin, with the amount of P-cofilin in HeLa cells without Y-27632 at zero time of plating taken as 1.0. Each value represents the mean of duplicate measurements.

Using this antibody, we examined changes in the level of endogenous P-cofilin during adhesion and spreading of HeLa cells on fibronectin-coated dishes. The level of P-cofilin gradually increased and reached a maximum level at 30 min after plating on fibronectin but did not change after plating on poly-l-lysine, which indicates that integrin signaling stimulates cofilin phosphorylation (Figure 8C). We next examined the effects of Y-27632 on the P-cofilin level before and after plating cells on fibronectin. The level of P-cofilin markedly decreased in Y-27632–treated suspended cells but increased gradually after plating on fibronectin in a time course similar to that of Y-27632–untreated cells (Figure 8, D and E). These results suggest that ROCK significantly contributes to the basal level of cofilin phosphorylation in HeLa cells before plating, but the integrin-mediated increase in cofilin phosphorylation is primarily regulated by a pathway(s) not related to ROCK. Similar patterns of time-dependent changes in TESK1 activation and P-cofilin level in response to plating cells on fibronectin, together with the finding that TESK1 kinase activity is independent of ROCK, suggest that TESK1 but not LIMK is responsible for integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation.

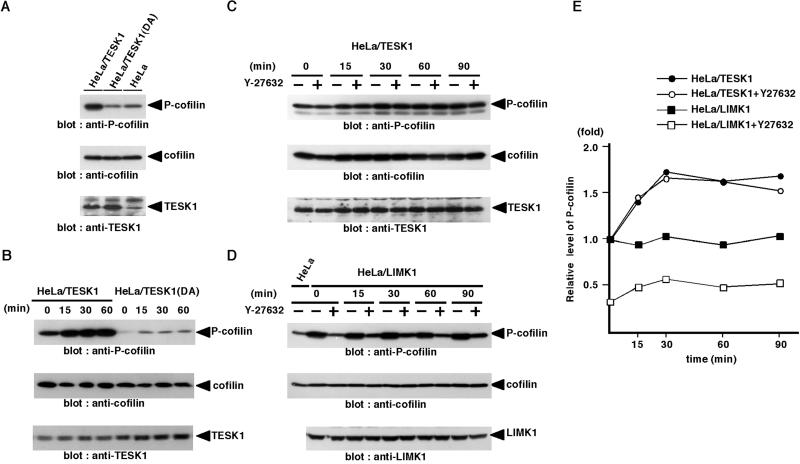

To further examine the role of TESK1 in integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation, we prepared HeLa cells stably expressing exogenous TESK1 (HeLa/TESK1) and TESK1(D170A) [HeLa/TESK1(DA)]. The levels of expression of TESK1 and TESK1(D170A) in these cells were approximately three- to fourfold higher than the level of endogenous TESK1, as estimated by immunoblotting (Figure 9A). The level of P-cofilin increased approximately threefold in HeLa/TESK1 cells and decreased to approximately half in HeLa/TESK1(DA) cells, compared with that in parental HeLa cells, whereas the levels of total cofilin in these cells were similar (Figure 9A). When HeLa/TESK1 cells were plated onto fibronectin-coated dishes, the level of P-cofilin increased and reached a maximum level at 30 min after plating (Figure 9B). On the other hand, the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/TESK1(DA) cells remained low even after plating on fibronectin (Figure 9B). These results further suggest that TESK1 is involved in cofilin phosphorylation stimulated by integrin signaling. We also examined the level of P-cofilin in HeLa cells expressing wild-type LIMK1 (HeLa/LIMK1). The level of P-cofilin in HeLa/LIMK1 cells was approximately threefold higher than the level in parental HeLa cells before plating (Figure 9D). However, in contrast to HeLa/TESK1 cells, the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/LIMK1 cells was not changed after cells were plated on fibronectin (Figure 9, D and E). Thus, it is likely that LIMK1 is involved in cofilin phosphorylation but does not significantly contribute to the increase in P-cofilin level induced by plating cells on fibronectin. In addition, treatment with Y-27632 reduced the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/LIMK1 cells before and after cells were plated on fibronectin but had no effect on the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/TESK1 cells before and after plating on fibronectin (Figure 9, C–E). Taken together these results suggest that TESK1 but not LIMK1 is involved in integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation during cell spreading and that integrin-mediated TESK1 activation and cofilin phosphorylation are mostly independent of ROCK.

Figure 9.

In vivo phosphorylation of cofilin by TESK1 is independent of Rho-ROCK signaling pathway. (A) HeLa cells stably expressing TESK1 (HeLa/TESK1) or TESK1(D170A) [HeLa/TESK1(DA)] were lysed, and the lysates were run on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-cofilin, anti-cofilin, and anti-TESK1 antibody. (B) HeLa/TESK1 or HeLa/TESK1(DA) cells were suspended and replated on fibronectin-coated dishes. At indicated times, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-cofilin, anti-cofilin, and anti-TESK1 antibody. (C and D) HeLa/TESK1 or HeLa/LIMK1 cells were suspended, incubated for 30 min with or without 10 μM Y-27632, and replated on fibronectin-coated dishes. At indicated times, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-cofilin, anti-cofilin, and anti-TESK1 (or anti-LIMK1) antibody. (E) Relative amounts of P-cofilin in HeLa/TESK1 or HeLa/LIMK1 cells treated with or without Y-27632 were plotted against the time after plating cells on fibronectin, with the amount of P-cofilin in HeLa/TESK1 or HeLa/LIMK1 cells without Y-27632 at zero time of plating taken as 1.0. Each value represents the mean of duplicate measurements.

Effects of TESK1 and TESK1(D170A) Expression on Integrin-mediated Stress Fiber and Focal Adhesion Formation

To further investigate the role of TESK1 in integrin-mediated signaling pathways, we next examined the effect of expression of wild-type or a kinase-inactive form of TESK1 on integrin-mediated stress fiber and focal adhesion formation. HeLa cells transfected with plasmids for TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) were suspended and then replated on fibronectin-coated dishes. When cells were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin 1.5 h after plating, stress fibers were markedly enhanced in TESK1-expressing cells (Figure 10A, top panel). In contrast, stress fibers were significantly weakened in TESK1(D170A)-expressing cells, compared with surrounding nontransfected cells (Figure 10A, bottom panel), which strongly suggests that endogenous TESK1 is involved in the stress fiber formation induced by integrin signaling. We also examined the effect of expression of wild-type or a kinase-dead form of TESK1 on focal adhesion formation by vinculin immunostaining. Formation of focal adhesions was substantially enhanced in wild-type TESK1-transfected cells but was reduced in TESK1(D170A)-transfected cells (Figure 10B). As summarized in Figure 10C, by plating cells on fibronectin, stress fibers were induced in 79% of the cells expressing control GFP and in 95% of cells expressing wild-type TESK1, but in only 44% of cells expressing TESK1(D170A). Similarly, focal adhesions were induced in 82% of cells expressing control GFP and in 98% of cells expressing wild-type TESK1, but in only 43% of cells expressing TESK1(D170A). Cells expressing a kinase-inactive form of LIMK1, LIMK1(D460A), induced stress fibers and focal adhesions by plating on fibronectin, to an extent seen with cells expressing control GFP (our unpublished results). Suppression of stress fibers and focal adhesions by TESK1(D170A) but not by LIMK1(D460A) strongly suggests that endogenous TESK1 but not LIMK1 plays an important role in the integrin-mediated signaling pathway to induce stress fibers and focal adhesions.

Figure 10.

Effects of TESK1 and TESK1(D170A) on fibronectin-induced stress fibers and focal adhesions. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid coding for TESK1 or TESK1(D170A) and cultured for 24 h in serum-free medium. Cells were trypsinized and replated on fibronectin-coated dishes. After 1.5 h, cells were fixed and stained with anti-TESK1 antibody and rhodamine-phalloidin (A) or anti-vinculin antibody (B). Arrowheads indicate cells expressing TESK1 or TESK1(D170A). Bar, 15 μm. (C) Ratio of cells containing stress fibers and focal adhesions induced by plating on fibronectin. Results are shown as means ± SEM of triplicate experiments. Cells expressing GFP were used as control.

DISCUSSION

Cofilin Phosphorylation by TESK1 and LIM-kinases

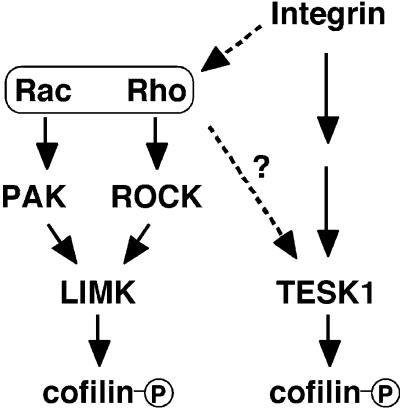

Cofilin plays an essential role in actin filament dynamics by enhancing depolymerization and severance of actin filaments (Bamburg et al., 1999). These activities of cofilin are abolished by phosphorylation at Ser-3; therefore, phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of cofilin at Ser-3 is regarded as one of the important mechanisms for regulating cofilin activities and actin filament dynamics. LIM-kinases were shown to be responsible enzymes for cofilin phosphorylation (Arber et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998). Here we provide evidence that TESK1 also has an ability to phosphorylate cofilin specifically at Ser-3 in vitro and in vivo and induce actin reorganization by phosphorylating cofilin. Thus, these findings suggest that cofilin phosphorylation in living cells is regulated by at least two pathways in which distinct types of protein kinases, LIM-kinases and TESK1, are involved. Considering the essential role of cofilin in actin filament dynamics, these kinases probably play important roles in regulating actin cytoskeletal remodeling and thereby in many cell activities, including cell motility, adhesion, and cytokinesis, by phosphorylating and inactivating cofilin. Most interestingly, we found that TESK1 is stimulated by an integrin-mediated signaling pathway but not by either ROCK or PAK, in contrast to LIM-kinases that are stimulated by Rho-ROCK and Rac-Pak pathways (Figure 11). Together with the total difference in extracatalytic structures, these results strongly suggest that LIM-kinases and TESK1, although they commonly phosphorylate cofilin, are regulated in different ways and play distinct roles in actin reorganization in living cells.

Figure 11.

Proposed scheme for multiple pathways for cofilin phosphorylation. TESK1 is activated downstream of integrin signaling pathways, whereas LIM-kinases are activated downstream of Rho-ROCK and Rac-PAK pathways. See text for details.

TESK1-induced Stress Fibers and Rho-ROCK Signaling Pathway

Rho and its downstream ROCK play a key role in the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions (Ridley and Hall, 1992; Leung et al., 1996; Amano et al., 1997; Ishizaki et al., 1997). ROCK induces stress fibers by increasing myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation through phosphorylating and inactivating MLC phosphatase and thereby increasing actomyosin-based contractility (Kimura et al., 1996). ROCK also phosphorylates and activates LIM-kinases, events that lead to phosphorylation and inactivation of cofilin and actin filament stabilization (Maekawa et al., 1999). Because TESK1 stimulates the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions, we extensively examined the relationships between TESK1 and the Rho-ROCK signaling pathway and obtained evidence that distinct from LIM-kinases, TESK1 is not downstream of ROCK. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that the kinase activity of TESK1 might be regulated by downstream effectors of Rho other than ROCK, such as rhophilin, rhotekin, and p160mDia, because in our assay systems we may overlook activation of TESK1 in cultured cells if activated by noncovalent association of activator proteins.

TESK1-induced stress fibers and focal adhesions were repressed by coexpression of C3 exoenzyme or ROCK(KD-IA), which suggests that the Rho-ROCK signaling pathway is required for the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions, although ROCK does not stimulate TESK1. Most likely, the ROCK-induced increase in MLC phosphorylation and actomyosin contractility is required for formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions (Kimura et al., 1996). Interestingly, Y-27632 treatment of TESK1-expressing cells led to the formation of lamellipodium-like actin organization and vinculin-assembled structures at cell margins, in place of stress fibers and focal adhesions. TESK1 therefore seems to have the potential to induce distinct patterns of actin organization, under conditions that ROCK signaling is abrogated. Several studies suggest that Rho and Rac mutually antagonize cellular activity, and the balance between Rho and Rac activity in cells determines the patterns of actin organization and substrate contact site morphology (Hirose et al., 1998; Rottner et al., 1999; Sander et al., 1999). Thus, it could be that lamellipodium-like actin organization and vinculin assembly in TESK1-expressing cells treated with Y-27632 are brought about by the preference of Rac activity against Rho activity as the result of inhibition of ROCK by Y-27632 treatment.

We also found that coexpression of TESK1(D170A) and ROCK(KD-IA) induces an almost complete loss of actin stress fibers and shrinking cell morphology. Because TESK1(D170A) and ROCK(KD-IA) are thought to function as dominant-negative forms against endogenous TESK1 and ROCK, respectively, both TESK1 and ROCK probably play an important role in maintaining cell morphology and cell adhesion by retaining certain levels of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions. Manser et al. (1997) reported a similar shrinking cell morphology induced by expression of an active form of PAK. Such morphological change may be due to the PAK activity to phosphorylate and inactivate MLC-kinase (Sanders et al., 1999), which leads to loss of actomyosin-based contractility and dissolution of stress fibers and focal adhesions, an event opposite that induced by ROCK/TESK1 activation. Thus, we assume that formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions are oppositely regulated by ROCK/TESK1 and PAK, and inhibition of both ROCK and TESK1 or excessive activation of PAK results in similar shrinking cell morphology.

Roles of TESK1 in Integrin-mediated Signaling Pathway

Integrins bind to ECM proteins such as fibronectin and transduce signals to control cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and migration (Clark and Brugge, 1995; Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1999). On binding to ECM proteins, integrins become clustered and form large protein complexes known as focal adhesions, through which integrins link to actin filaments (Burridge et al., 1997). Previous studies identified a number of proteins that are assembled into focal adhesions on integrin stimulation, but little is known about signaling pathways of integrin-mediated actin reorganization. In the present study we have found that the kinase activity of TESK1 as well as the level of cofilin phosphorylation are elevated by plating cells on fibronectin. Time courses of changes in TESK1 activity and P-cofilin level after plating are similar, and the level of P-cofilin increased in cells stably expressing TESK1 but decreased in cells expressing TESK1(D170A). We have also found that wild-type TESK1 enhanced and a kinase-inactive form of TESK1 suppressed the fibronectin-induced formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. Taken together, these results suggest that TESK1 plays a key role in cofilin phosphorylation and actin reorganization stimulated by integrin signaling. In contrast, only a small increase in the kinase activity of LIMK1 was detected after plating cells on fibronectin, and a kinase-inactive form of LIMK1 had no apparent effect on integrin-mediated stress fiber and focal adhesion formation. Furthermore, the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/LIMK1 cells increased before plating but did not change after plating cells on fibronectin. Accordingly, it is presumable that LIMK does not significantly contribute to integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation and actin reorganization.

Treatment with Y-27632 significantly reduced the level of P-cofilin before plating but had no apparent effect on the fibronectin-stimulated cofilin phosphorylation, which indicates that ROCK is involved in maintaining the basal level of P-cofilin but has little effect on integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation. In addition, treatment with Y-27632 reduced the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/LIMK1 cells before and after plating cells on fibronectin but did not affect the level of P-cofilin in HeLa/TESK1 cells. Together with the finding that ROCK activates LIMK1 but not TESK1 in in vitro and in vivo reactions, these results suggest that TESK1 principally contributes to the integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation, which is independent of ROCK, whereas LIMK1 contributes to cofilin phosphorylation before plating that is dependent on ROCK activity.

Previous studies implicated Rho and Rac in integrin-mediated cell adhesion and spreading (Clark et al., 1998; Price et al., 1998; Ren et al., 1999). Rho was significantly activated by plating cells on fibronectin when cells were maintained in 1% serum, but its activation was very modest under serum-free conditions (Ren et al., 1999). Only a small increase in LIMK1 activity and Y-27632 insensitivity of cofilin phosphorylation after cells were plated on fibronectin in our assays may be explained by our assay conditions in which serum was depleted. It could be that under serum-supplemented conditions TESK1 and Rho signals cooperatively function in integrin-mediated stress fiber and focal adhesion formation. In fibroblasts, plating cells on fibronectin led to the rapid activation of PAK with the maximal activity at 5–10 min after plating (Price et al., 1998). If this is also the case in HeLa cells, PAK activation may contribute to the early phase of integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation through activation of LIMK, but activation of LIMK1 was barely detectable at 15 min after plating in our assay. Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of the Rac-PAK pathway in integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation in respective cells.

The C-terminal region of TESK1 is rich in proline residues and contains several ProX-X-Pro motifs, known to be recognized by SH3 domains. TESK1 may be localized and activated at the sites of cell adhesion by interaction with SH3-containing focal adhesion proteins, such as Crk, Nck, and CAS, through its C-terminal proline-rich region. Focal adhesion proteins, such as CAS and paxillin, are phosphorylated on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues integrin during stimulation (Schlaepfer et al., 1997; Brown et al., 1998). Because TESK1 is activated by integrin stimulation, TESK1 may play a role in actin reorganization and focal adhesion formation by phosphorylating these focal adhesion proteins, in addition to phosphorylating cofilin.

Physiological Roles of TESK1

TESK1 mRNA is predominantly expressed in testicular germ cells at stages of late pachytene spermatocytes to round spermatids, which suggests a role of TESK1 in spermatogenesis (Toshima et al., 1995, 1998). However, the actual function of TESK1 in testicular germ cells remains unknown. Drosophila null mutants of the center divider (cdi) gene, which encodes an orthologue of TESK1, are larval lethal, suggesting an important role for the cdi gene product in fly development (Matthews and Crews, 1999). The cdi gene is prominently expressed in midline cells of the fly embryonic CNS. Because we observed that TESK1 gene is expressed in specific regions of the mouse embryonic CNS (our unpublished data), there may be functional relationships between fly cdi and mammalian TESK1 during neuronal development. On the other hand, whether the cdi gene is expressed in fly testes or whether mutation of the cdi gene affects fly spermatogenesis remains to be determined. Using Drosophila genetics to explore the functions of TESK1 in spermatogenesis and neurogenesis is a challenging theme.

Drosophila twinstar (tsr) mutants, in which expression of the tsr gene encoding a Drosophila cofilin orthologue is reduced, are lethal in late larval or pupal stages (Gunsalus et al., 1995). Cytological studies revealed frequent failures in cytokinesis in larval neuroblasts and testicular meiotic cells. Mutant spermatocytes exhibited delayed centrosome migration and a defect in contractile ring disassembly of two meiotic cell divisions (Gunsalus et al., 1995). A similar phenotype was seen in testes treated with cytochalasin B, an inhibitor of actin polymerization. These phenotypes in mutant spermatocytes are regarded as the aberrant actin cytoskeletal reorganization, and the properly regulated actin assembly and disassembly are likely important for normal centrosome migration and normal contractile ring formation and dissolution during cytokinesis. TESK1 in testes may play a role in these processes during spermatogensis by regulating the activity of cofilin. On the basis of activity of TESK1 to phosphorylate cofilin, it seems appropriate to determine physiological functions of TESK1, as related to actin cytoskeletal reorganization.

In conclusion, our evidence shows that cofilin phosphorylation is regulated by at least two distinct types of protein kinases: LIM-kinases and TESK1. Although LIM-kinases are activated by Rac-PAK and Rho-ROCK signaling pathways, TESK1 is stimulated by integrin-mediated signaling pathways and significantly contributes integrin-mediated cofilin phosphorylation and actin reorganization (Figure 11). Our findings will provide new insights into the integrin-mediated signaling pathways to induce actin cytoskeletal remodeling and focal adhesion formation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Saburo Aimoto (Osaka University) for phosphopeptide synthesis, Dr. Takashi Obinata (Chiba University) for providing MAB-22 anticofilin monoclonal antibody, Dr. Kyoko Ohashi (Tohoku University) for two-dimensional gel analysis, and Dr. Yukio Fujiki (Kyushu University) for advice and encouragement. This work was supported by research grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan, and the Japan Society of the Promotion of Science Research for the Future, and grants from Naito Foundation, Welfide Foundation, and Uehara Memorial Foundation (to K.M.).

Abbreviations used:

- ADF

actin depolymerizing factor

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- LIMK1

LIM-kinase 1

- LIMK2

LIM-kinase 2

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

- ROCK

Rho-associated coiled-coil–forming protein kinase

- TESK1

testicular protein kinase 1

REFERENCES

- Abe H, Ohshima S, Obinata T. A cofilin-like protein is involved in the regulation of actin assembly in developing skeletal muscle. J Biochem. 1989;106:696–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew BJ, Minamide LS, Bamburg JR. Reactivation of phosphorylated actin depolymerizing factor and identification of the regulatory site. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17582–17587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Chihara K, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Nakamura N, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions enhanced by Rho-kinase. Science. 1997;275:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Tanabe K, Eto T, Narumiya S, Mizuno K. LIM-kinase 2 induces formation of stress fibers, focal adhesions and membrane blebs, dependent on its activation by Rho-associated kinase-catalyzed phosphorylation at threonine-505. Biochem J. 2001;354:149–159. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, Caroni P. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature. 1998;393:805–809. doi: 10.1038/31729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamburg JR, McGough A, Ono S. Putting a new twist on actin: ADF/cofilins modulate actin dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:364–370. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Perrotta JA, Turner CE. Serine and threonine phosphorylation of the paxillin LIM domains regulates paxillin focal adhesion localization and cell adhesion to fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1803–1816. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Zhong C. Focal adhesion assembly. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:342–347. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Bernstein BW, Bamburg JR. Regulating actin-filament dynamics in vivo. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EA, King WG, Brugge JS, Symons M, Hynes RO. Integrin-mediated signals regulated by members of the Rho family of GTPases. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:573–586. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signaling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:253–259. doi: 10.1038/12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JA, Khokhlatchev A, Stippec S, White MA, Cobb MH. Differential effects of PAK1-activating mutations reveal activity-dependent and -independent effects on cytoskeletal regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28191–28198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunsalus KC, Bonaccorsi S, Williams E, Verni F, Gatti M, Goldberg ML. Mutations in twinstar, a Drosophila gene encoding a cofilin/ADF homologue, result in defects in centrosome migration and cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1243–1259. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose M, Ishizaki T, Watanabe N, Uehata M, Kranenburg O, Moolenaar WH, Matsumura F, Maekawa M, Bito H, Narumiya S. Molecular dissection of the Rho-associated protein kinase (p160ROCK)-regulated neurite remodeling in neuroblastoma N1E-115 cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1625–1636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki T, Naito M, Fujisawa K, Maekawa M, Watanabe N, Saito Y, Narumiya S. p160ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein kinase, works downstream of Rho and induces focal adhesions. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, et al. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung T, Chen X-Q, Manser E, Lim L. The p160 RhoA-binding kinase ROKα is a member of a kinase family and is involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5313–5327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Boku S, Watanabe N, Fujita A, Iwamatsu A, Obinata T, Ohashi K, Mizuno K, Narumiya S. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science. 1999;285:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manser E, Huang H-Y, Loo T-H, Chen X-Q, Dong J-M, Leung T, Lim L. Expression of constitutively active α-PAK reveals effects of the kinase on actin and focal complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1129–1143. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BB, Crews ST. Drosophila center divider gene is expressed in CNS midline cells and encodes a developmentally regulated protein kinase orthologous to human TESK1 DNA. Cell Biol. 1999;18:435–448. doi: 10.1089/104454999315150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Okano I, Ohashi K, Nunoue K, Kuma K, Miyata T, Nakamura T. Identification of a human cDNA encoding a novel protein kinase with two repeats of the LIM/double zinc finger motif. Oncogene. 1994;9:1605–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon A, Drubin DG. The ADF/cofilin proteins: stimulus-responsive modulators of actin dynamics. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1423–1431. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.11.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama K, Iida K, Yahara I. Phosphorylation of Ser-3 of cofilin regulates its essential function on actin. Genes Cells. 1996;1:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.05005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narumiya S, Ishizaki T, Watanabe N. Rho effectors and reorganization of actin cytoskeleton. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K, Nagata K, Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Mizuno K. Rho-associated kinase ROCK activates LIM-kinase 1 by phosphorylation at threonine 508 within the activation loop. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3577–3582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K, Nagata K, Toshima J, Nakano T, Arita H, Tsuda H, Suzuki K, Mizuno K. Stimulation of Sky receptor tyrosine kinase by the product of growth arrest-specific gene 6. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22681–22684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano I, Hiraoka J, Otera H, Nunoue K, Ohashi K, Iwashita S, Hirai M, Mizuno K. Identification and characterization of a novel family of serine/threonine kinases containing two N-terminal LIM motifs. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31321–31330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price LS, Leng J, Schwartz MA, Bokoch GM. Activation of Rac and Cdc42 by integrins mediates cell spreading. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1863–1871. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X-D, Kiosses WB, Schwartz MA. Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 1999;18:578–585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AJ, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell. 1992;70:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottner K, Hall A, Small JV. Interplay between Rac and Rho in the control of substrate contact dynamics. Curr Biol. 1999;9:640–648. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander EE, ten Klooster JP, van Delft S, van der Kammen RA, Collard JG. Rac downregulates Rho activity: reciprocal balance between both GTPases determines cellular morphology and migratory behavior. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1009–1021. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders LC, Matsumura F, Bokoch GM, de Lanerolle P. Inhibition of myosin light chain kinase by p21-activated kinase. Science. 1999;283:2083–2085. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Broome MA, Hunter T. Fibronectin-stimulated signaling from a focal adhesion kinase-c-Src complex: involvement of the Grb2, p130CAS, and Nck adaptor proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1702–1713. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine A, Fujiwara M, Narumiya S. Asparagine residue in the rho gene product is the modification site for botulinum ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8602–8605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi T, Matsumoto K, Takai Y, Nakamura T. Cofilin phosphorylation and actin cytoskeletal dynamics regulated by Rho- and Cdc42-activated LIM-kinase 2. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1519–1532. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshima J, Koji T, Mizuno K. Stage-specific expression of testis-specific protein kinase 1 (TESK1) in rat spermatogenic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:107–112. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshima J, Ohashi K, Okano I, Nunoue K, Kishioka M, Kuma K, Miyata T, Hirai M, Baba T, Mizuno K. Identification and characterization of a novel protein kinase, TESK1, specifically expressed in testicular germ cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31331–31337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshima J, Tanaka T, Mizuno K. Dual specificity protein kinase activity of testis-specific protein kinase 1 and its regulation by autophosphorylation of serine-215 within the activation loop. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12171–12176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehata M, et al. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–994. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Higuchi O, Ohashi K, Nagata K, Wada A, Kangawa K, Nishida E, Mizuno K. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature. 1998;393:809–812. doi: 10.1038/31735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]