Abstract

Objective: The prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Latin America varies across different studies but an intermediate risk and increased frequency of the disease have been reported in recent years. The circumstances of Latin American countries are different from those of Europe and North America, both in terms of differential diagnoses and disease management.

Methods: An online survey on MS was sent to 855 neurologists in nine Latin American countries. A panel of nine experts in MS analyzed the results.

Results: Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations were outlined with special emphasis on the specific needs and circumstances of Latin America. The experts proposed guidelines for MS diagnosis, treatment, and follow up, highlighting the importance of considering endemic infectious diseases in the differential diagnoses of MS, the identification of patients at high risk of developing MS in order to maximize therapeutic opportunities, early treatment initiation, and cost-effective control of treatment efficacy, as well as global assessment of disability.

Conclusions: The experts recommended that healthcare systems allocate a longer consultation time for patients with MS, which must be conducted by neurologists trained in the management of the disease. All drugs currently approved must be available in all Latin American countries and must be covered by healthcare plans. The expert panel supported the creation of a permanent forum to discuss future clinical and therapeutic recommendations that may be useful in Latin American countries.

Keywords: glatiramer acetate, immunomodulators, interferon-beta, mitoxantrone, multiple sclerosis, natalizumab

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating neurological disorder that mainly affects individuals between the ages of 20 and 50 years. Approximately 85% of patients experience an initial course with relapses and remissions (relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, RRMS). It is estimated that some 50,000 individuals present with MS in Latin America [Luetic, 2008]. The prevalence of MS in Latin American countries ranges between 1.48 and 25/100,000 population [Díaz et al. 2010; Cristiano et al. 2009, 2008; Melcon et al. 2008; Toro et al. 2007; Velázquez Quintana et al. 2003]. The available data on Latin American countries are limited, and the prevailing circumstances are different from those noted in Europe and the USA in several respects, including the lower incidence and prevalence of the disease, the differential diagnoses, and the access to diagnostic methods. In order to collect updated information, an online survey on MS was sent to general neurologists working in Latin American countries. A panel of nine MS experts of the region was convened to discuss the outcome of the survey and harmonize the diagnostic and therapeutic criteria applied in Latin America.

This paper, which also presents the outcomes of a survey carried out among Latin American neurologists, contains consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of MS in Latin America that are in line with current international recommendations. Its main purpose is to set common guidelines with minimum requirements for the management of MS across countries with varying political and economic backgrounds, thus integrating the available evidence on the optimization of treatment of MS patients.

Materials and methods

A survey on the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to MS was conducted among neurologists of the participating Latin American countries. A total of 855 surveys were sent online. Participating countries included Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Table 1 summarizes survey participation and estimations of MS prevalence by country.

Table 1.

Latin American survey on multiple sclerosis: number of surveys sent and received, and disease prevalence by country.

| Country | Surveys sent | Surveys completed | Prevalence of multiple sclerosis(100,000 population) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 258 | 70 | 15.9 |

| Brazil | 360 | 46 | 10–15 |

| Colombia | 26 | 26 | 1.48–6.0 |

| Chile | 53 | 8 | 12 |

| Mexico | 110 | 25 | 12–15 |

| Panama | 3 | 3 | - |

| Peru | 30 | 11 | 7.69* |

| Venezuela | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Uruguay | 11 | 11 | 25 |

| Total | 855 | 204 |

Data correspond to the city of Lima only.

A panel of nine MS expert neurologists was selected based on the following criteria: country of residence and number of inhabitants; affiliation to educational institutions; clinical experience in MS (all experts had more than 15 years of specialization in this area); research interest. The experts reviewed the most recently published evidence on the diagnosis, treatment, and overall management of MS. Before the meeting, approximately 100 papers were made available to the nine panelists through a purpose-set website. During the consensus meeting, the experts discussed the outcomes of the survey and key issues regarding both MS and clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) based on the references they had reviewed in advance. Consensus was defined as an agreement of at least seven out of the nine panelists (77.77%). Most of the findings of the expert panel are based on clinical trials supported with evidence level 1 (recommendation grade A) as defined by evidence-based medicine guidelines.

Discussions focused on three main areas: (a) the diagnosis of MS, with an emphasis on the identification of patients at risk of developing the disease; (b) early treatment; (c) long-term treatment, including clinical follow up, treatment failure, dose adjustment, drug switch, control of therapeutic efficacy and escalation, and disease progression. Diagnosis was reviewed under a clinical and paraclinical perspective, with focus on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, as well as on evoked potentials (EPs) determination. The discussion on therapeutic recommendations focused on the disease-modifying agents developed in the latest years. These drugs comprise glatiramer acetate, interferon (IFN) beta-1a intramuscular (i.m.) and subcutaneous (s.c.), IFN beta-1b, natalizumab, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone. The experts highlighted that the availability in Latin American countries of the different drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency varies broadly according to the regulations of their respective healthcare systems. The panel further analyzed comparative trials on the efficacy of such drugs and also examined new drugs under research for the treatment of the disease.

Results and discussion

Out of the 855 surveys sent, 204 responses were received (23.85%): 88% of participants were general neurologists; 8% of respondents had fewer than 5 years of clinical practice, 46% had 5–10 years, 11% 10–20 years, 35% had more than 20 years of clinical practice; 19% of respondents treat, on average, over 20 MS patients in any given month, 21%, between 10 and 20 patients, 27% between five and 10 patients, and 33% of respondents treat fewer than five MS patients. Table 2 summarizes the questions posed to participating neurologists and their responses.

Table 2.

Latin American survey on multiple sclerosis: questions posed and percentage answers (n = 204).

| Diagnosis |

| 1. Do you find clinical criteria useful? Do you use clinical criteria in your daily practice? |

| 99% of the respondents considered that diagnostic criteria (McDonald, as revised in 2005) are useful, and 92% of them answered that they used these criteria in their clinical practice. |

| 2. Do you have easy access to oligoclonal bands detection by isoelectric focusing? |

| 55% of respondents declared that they have no access to oligoclonal bands detection in cerebrospinal fluid. |

| 3. Do you have easy access to visual evoked potentials determination? |

| 82% of survey participants declared that there is adequate access to visual evoked potentials determination in their country. |

| 4. Do you have easy access to carrying out MRIs on your patients? When do you consider it necessary to perform MRIs? |

| 94% of respondents declared that they have sufficient access to MRI scans, and considered that the appropriate timepoints for MRI scans were upon diagnosis, every 6 months (if the diagnosis is not clear), once a year (irrespective of patient’s progression), with disease progression, and with relapses. |

| 5. In your country, are there any guidelines on the frequency of MRI scans? |

| 86% of survey participants declared that there are no guidelines regarding the frequency for MRI scans in their respective countries. |

| Treatment |

| 6. Do you agree with the treatment of CIS? |

| 92% of respondents considered that CIS must be treated. |

| 7. What is your first-line treatment choice? |

| Most of participating neurologists start treatment with glatiramer acetate or IFN beta-1a i.m., IFN beta-1a s.c. (22 µg or 44 µg), or IFN beta-1b. Some prescribe azathioprine as a starting drug because they do not have access to immunomodulating agents, or because these drugs are not covered by healthcare plans. |

| 8. Is the use of generic or biosimilar drugs approved in your country? |

| 64% of neurologists stated that the use of generic drugs is approved in their country. |

| Overall management |

| 9. Do you consider the annual number of relapses when defining treatment failure? How many relapses a year? |

| 96% of survey participants consider the number of annual relapses to determine whether there is treatment failure. Of these, 73% consider that there is treatment failure if the patient presents with two or more attacks per year, and 26%, if the patient presents with one or more relapses per year. |

| 10. When do you consider that a relapse has occurred? |

| 50% of respondents considered that patients have a relapse when symptoms persist at least for 24 h, while the rest opined that symptoms must persist at least for 48 h. |

| 11. Do you consider that progression is an indicator of treatment failure? Which factors do you take into account to define progression? |

| 90% of neurologists considered that progression is an indicator of treatment failure. Most of them defined progression based on a change in the EDSS score sustained for 6 months. |

| 12. Do you use assessment scales in your daily practice? If yes, which? |

| 96% of survey respondents stated that they were used to administering the EDSS, 62% with cognitive assessments, and 50% with MSF Composite. However, only 42% of participants stated that they administer any of these scales at each visit. Of these, 79% administer the EDSS, 15%, cognitive assessments, and 13%, the MSF Composite. |

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MSF Composite, Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite.

Diagnosis

The discussion on diagnosis dealt with clinical and radiological diagnostic criteria, CSF analysis and visual EP determination, and the differential diagnoses specific to Latin America that must be taken into account upon issuing a diagnosis of MS.

The diagnosis of MS is confounded by the fact that its signs and symptoms may resemble those of other conditions. As there are no specific tests to identify the disease, diagnosis continues to be largely clinical, which determines the need to apply diagnostic criteria. Clinical diagnosis requires a complete medical history and neurological examination. The experts underscored that the clinical examination of MS patients, particularly in the first visit, requires a special dedication, and recommended healthcare systems to allocate these patients a longer visit time than usual with other patients groups. The experts also highlighted that neurologists treating these patients must have extensive experience in the management of MS.

Over time, different criteria sets have been developed to support a diagnosis of MS in the clinical practice. Historically, the most relevant have been those proposed by Schumacher and colleagues, Poser and colleagues, and McDonald and colleagues [McDonald et al. 2001; Poser et al. 1983; Schumacher et al. 1965]. The revisions to the McDonald criteria made by Polman and colleagues are currently the most frequently used criteria for the diagnosis of MS [Polman et al. 2011, 2005].

The experts highlighted the relevance of analyzing CSF to detect the presence of oligoclonal bands through isoelectric focusing [Rojas et al. 2010; Tintoré et al. 2008]. This technique is specific and sensitive; on the contrary, the use polyacrylamide gel may yield up to 50% false negative results. In any case, the experts noted that in Latin America there are only a few centers duly validated to perform isoelectric focusing determinations, and the tests should be performed at those reference centers. The other useful CSF test to diagnose MS is the immunoglobulin G index.

Likewise, visual EPs are useful in confirming the involvement of the optic pathway in case of diagnostic uncertainty, and to identify subclinical abnormalities at the onset of the disease. In patients with established optic neuritis, visual EPs add no information. The technique of choice is checkerboard stimulation; EPs to flash provide little information and are not useful, except among patients with severe visual field restriction. As abnormal findings are permanent, visual EPs are not useful for patient follow up.

The McDonald criteria as revised by Polman and colleagues [Polman et al. 2005] introduced changes in the demonstration of dissemination in time and space through MRI, with subsequent key revisions with respect to the use and interpretation of imaging criteria [Polman et al. 2011]. Moreover, the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers issued guidelines on the most appropriate MRI technique [Simon et al. 2006]. These include obtaining weighted images at T1 and T2 with gadolinium contrast, a sagittal section at T2, a coronal section to examine the optic nerve, a sagittal section to view the spinal cord, and a sagittal section to compare it with the lesions observed elsewhere. If any of the lesions are dubious, 0.5 mm slices must be obtained. Although it is recommended to use 1.5 tesla scanners, where such equipment is not available, the experts considered that MRI scans with lower resolution are equally useful for diagnosis [Filippi et al. 2006]. In centers with magnetization-transfer (MT) capabilities, these images may aid diagnosis, although there are no standards and longitudinal follow up with MT MRI is difficult in daily clinical practice.

The differential diagnoses that must be taken into account are multiple, and may be found in other sources [Rolak, 2005]. The experts highlighted the importance of including regional diseases that are specific to Latin America, especially infections (Table 3).

Table 3.

Specific differential diagnoses that must be considered in Latin American countries.

| Causes | Main diseases | Main recommended tests |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular | Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy | Genetic tests Family history of neurological disorders CSF generally normal |

| Lacunar infarcts | Brain MRI scan Carotid Doppler ultrasound Echocardiogram |

|

| Infectious (CNS involvement) | Brucellosis |

Brucella culture in CSF Antibody detection (microagglutination, Coombs or Bengali rose) CSF alterations (cells >10/mm3; proteins >0.45 g/L; glucose <4 g/L or <40% of glycemia) with brucellosis confirmed at another body site |

| Cysticercosis | ELISA in blood and CSF Western Blot (immunoelectrotransfer) in blood and CSF |

|

| Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 | ELISA Western Blot Immunofluorescence Particle agglutination Virus detection |

|

| Tuberculosis | MRI scan | |

| Immune | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Serology with antinuclear antibody and anti-dsDNA |

| Isolated CNS vasculitis | Autoantibodies Angiography |

|

| Metabolic | Vitamin B12 deficiency | Abnormal blood test results Low serum B12, methylmalonic acid and homocysteine concentrations |

| Malnutrition | General clinical examination | |

| Hematological | Thrombophilia | Inherited: C and S proteins, antithrombine, APCr, prothrombin 20210G polymerase chain reaction Acquired: according to presumptive diagnosis |

CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The concept of CIS was developed following Polman and colleagues’ revision of the McDonald criteria [Polman et al. 2005]. The term is used to describe the first acute neurological episode lasting more than 24 h caused by inflammation or demyelinization at one or more central nervous system (CNS) sites.

There are different MRI diagnostic criteria for CIS. These criteria have changed over time [Swanton et al. 2006], and must be correlated with the clinical manifestations. Recently, the European multicenter network for the study of MS through MRI scans (MAGNIMS) proposed new criteria for dissemination in time and space, as well as a diagnostic algorithm to predict the conversion of CIS into clinically defined MS [Montalban et al. 2010].

The widespread availability of MRI as an imaging diagnostic test has led to the incidental finding of white matter lesions at the CNS that are suggestive of MS and not attributable to any other disease in asymptomatic patients. These lesions are known as ‘radiologically isolated syndrome’ [Okuda et al. 2009]. The natural history of these lesions and the evolution of these patients regarding their risk of developing MS are unclear, and further evidence is required to establish this risk.

Treatment

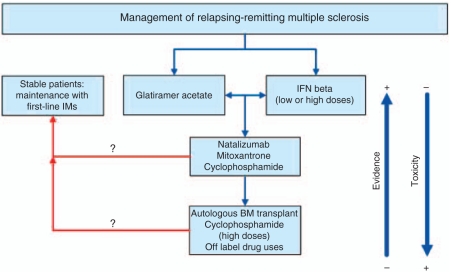

The experts examined the treatment of RRMS and its possible variants, including drug switching and escalation therapies.

Treatment of RRMS must be started with the drug with the best risk-benefit balance [Garcea et al. 2009]. To date, the first-line drugs regularly used for the treatment of MS include: glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®) [Johnson et al. 1995], 20 mg/day s.c.; IFN beta-1a, 30 µg/week i.m. (Avonex®) [Jacobs et al. 1996]; IFN beta-1a, 22 µg three times a week s.c. or 44 µg three times a week s.c. (Rebif®) [PRISMS Study Group, 1998]; IFN beta-1b, 250 µg every other day s.c. (Betaferon®) [IFN-beta MS Study Group, 1993]. The experts recommended not prescribing immunosuppressive drugs (azathioprine) as initial therapy.

Several comparative studies [Achiron and Fredrikson, 2009; Cadavid et al. 2009; O’Connor et al. 2009; Mikol et al. 2008] have proved that glatiramer acetate and high-dose IFNs are similarly effective (evidence level 1, recommendation grade A). Likewise, high IFN doses are more effective than low doses (recommendation grade B). The experts stated that all drugs are useful at the doses mentioned above, and considered that the final therapeutic decision must be made on the basis of available evidence and together with the patient, taking into account factors such as expected treatment adherence and the potential side effects of the drug. A follow-up visit should be scheduled at 3–6 months to control the course of the disease. No treatment change is necessary if patients are stable.

In some cases, however, it is necessary to switch medications or to adjust the dose, either due to treatment failure or to the development of severe and/or serious adverse events (requiring hospitalization). Patients who initially respond to IFN but who later present with treatment failure must be switched from IFN to glatiramer acetate. Conversely, in patients who initially respond to glatiramer acetate and become refractory to treatment, IFN should be administered. Upon treatment failure, the patient must be switched to a drug with a higher strength (escalation therapy) [Rieckmann et al. 2008], which usually also has a higher toxicity. The purpose of escalation therapy is to reach an acceptable risk-benefit balance, in which the condition of ‘acceptable’ is always associated with the severity of the disease. The treating physician must define the threshold at which the therapeutic effectiveness will be considered suboptimal and treatment must progress to the second level, that is, administration of natalizumab, mitoxantrone or cyclophosphamide. Regarding natalizumab, the experts recommended using it only under a drug surveillance program (such as the TOUCH program in the USA, or the European TYGRIS program, or a combination of both), which enables monitoring the development of potential adverse events, particularly progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Before administering the drug, the physician must order laboratory tests including CD4 and CD8 counts, a chest X-ray, and an MRI scan. Patients above 60 years of age, those previously treated with immunosuppressive agents (a wash-out period of at least 6 months must be allowed before administering natalizumab), and patients living with HIV are at a higher risk of adverse events. Furthermore, experts underscored that both the physician who administers the drug and the infusion center must be broadly experienced in the management of the drug and must be certified for its administration.

In the event that previous treatments are not effective and MRI scans continue to reveal inflammatory activity, or if the patient continues to relapse, the neurologist may consider escalation to a third level of treatment, including the use of drugs not approved for the treatment of MS (off-label indications), such as rituximab [Hauser et al. 2008] or alemtuzumab (phase III trials underway) [Coles et al. 2008]; or cyclophosphamide at high doses [Krishnan et al. 2008]; or bone marrow transplant. Figure 1 summarizes the proposed treatment algorithm for RRMS.

Figure 1.

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treatment algorithm.BM, bone marrow; IFN, interferon; IM, immunomodulating agents.

Regarding CIS, the treatment of the first acute episode was studied in four clinical trials [Kappos et al. 2006, 2007, 2009; Comi et al. 2001, 2009]. In all of them, the episode was treated with high methylprednisolone doses, and the trials evaluated the risk of subsequent conversion to clinically definite MS, that is, the occurrence of a second acute episode, which was the primary endpoint in all studies. These studies represent evidence level 1 (recommendation grade A) and all showed that the administration of immunomodulating agents during CIS reduces the risk of a second demyelinating episode, without significant differences noted among the different types of immunomodulating agents [Clerico et al. 2008; Melo et al. 2008]. The criteria for treating CIS with disease-modifying agents are based on the identification of those patients at high risk of developing MS. According to this evidence, the experts recommend treating CIS, and that all effective drugs must be made available to all patients.

Irrespective of baseline therapy, the experts agreed that relapses must be treated with the administration of high intravenous (i.v.) doses of methylprednisolone. The dose ranges from 500 mg/day for 5 days to 1 g/day for 3–5 days (evidence level 1, recommendation grade A) [Durelli et al. 1986]. The administration of 2 g/day for 5 days (evidence grade U) has also been described. The total dose is administered i.v. during 2–4 hours, and blood pressure and heart rate must be monitored in order to identify potential side effects caused by corticosteroids at an early stage, such as hypotension. In the case of severe relapses that do not respond to steroid therapy, or in the case of adverse events, treatment with plasmapheresis (recommendation grade B) may be considered. In all other cases, there is no evidence to support the use of plasmapheresis in the treatment of MS. There is no strong evidence in support of the use of natalizumab, i.v. immunoglobulin, or a second course of corticosteroids during relapses. Furthermore, experts discourage the use of oral corticosteroids instead of i.v. methylprednisolone in these cases, as well as the additional administration of prednisone orally after i.v. administration with maintenance purposes and dose tapering. There are no data showing that this therapeutic approach improves the course of relapses.

The situation with generic or biosimilar drugs varies from country to country in terms of the availability of these drugs, their price in absolute terms and relative to brand name drugs, and local regulations governing their use. The experts highlighted that the efficacy, safety, and bioequivalence of these drugs have not been researched in clinical trials. The final responsibility for patient treatment lies with the treating physician, who is the only one authorized to introduce changes in the medication prescribed.

Treatment failure has been defined as a function of the frequency of relapses, but it must be evaluated in relation to the frequency of relapses before treatment. The expert panel decided to use the criteria of the MS treatment optimization guide by Freedman and colleagues [Freedman et al. 2004; International Working Group for Treatment Optimization in MS, 2004] to define suboptimal response.

The first factor that must be evaluated in case of treatment failure is treatment adherence, as the leading cause of lack of response is patient nonadherence to treatment. The expert panel stated that the treating neurologist must establish a control method to ensure strict compliance with treatment (100% adherence), although at present there are no studies to determine the best choice. The inclusion of nurses specialized in MS in the treatment team is considered especially useful to attain this goal. Neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) are another factor associated with treatment failure. To date, none of the Latin American countries has NAbs testing capabilities, except by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which does not have the adequate sensitivity. The role of NAbs on the progression of MS is controversial [Bertolotto, 2009; Goodin et al. 2007], and, in fact, their determination does not alter the therapeutic approach. In patients treated with IFN and with persistently high NAbs titres, their determination upon treatment failure might play a role.

There are several new drugs that have been recently approved or are under research for the treatment of MS [DeAngelis and Lublin, 2008], such as oral treatments, monoclonal antibodies, the T-cell vaccine, and the recombining DNA vaccine. Given the interest of patients and neurologists, and the evidence level available to date, the experts only discussed the approved oral treatments and monoclonal antibodies available in the marketplace, and used as off-label treatments for MS.

Fingolimod, an immunotherapeutic agent, was studied in two phase III trials [Cohen et al. 2010; Kappos et al. 2010]. The first one demonstrated a decrease in the number of relapses, a slowdown of disability progression time, a reduction in T2 and T1 lesion volume and gadolinium-enhancing lesion count, and a decrease in volume loss. The second trial found a lower relapse rate, a decreased number of new lesions or decreased size of T2 lesions, less atrophia, and no significant differences in terms of progression of disability among the different treatment groups. This drug has been introduced into the marketplace or is pending approval in several countries. However, because the experience with this drug is limited and there are no long-term side effect data available, a closer and more thorough follow up of patients is required than with the currently employed drugs.

There are several monoclonal antibodies currently used in the treatment of MS that have been approved for other indications. All of them have been subject to phase II trials and have phase III trials underway or planned. Their availability in the marketplace allows for off-label uses in patients with especially severe or rapidly evolving MS. Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody, and early trials with this agent in secondary progressive MS were negative. However, in cases of RRMS, positive findings have been obtained in a phase II clinical trial of this agent versus IFN beta-1a [Coles, 2008]. The trial showed a 75% reduction in the annual relapse rate, a 65% decreased risk of progression sustained at 6 months, decreased T2 lesion volume, and decreased atrophia. Phase III trials with this drug are currently underway. Rituximab is a chimeric antibody; studies have shown controversial results [Bar-Or et al. 2008], and this agent will be replaced with ocrelizumab, a fully human antibody. Daclizumab, a monoclonal antibody, has been used in the treatment of kidney transplant rejections. A first phase II, open-label trial was conducted with patients that had not responded to IFN therapy, to whom daclizumab was added [Wynn et al. 2010]. The outcomes showed a 72% decrease in the total count of gadolinium-enhancing lesions, and a reduction in the annual relapse rate, the progression of disability, and the annual progression rate. Phase III trials are currently underway.

Overall management

In this section, the experts considered patient follow up, relapses and disease progression, cognitive impairment, and quality-of-life assessments.

In order to evaluate treatment efficacy, the guidelines of the US National Multiple Sclerosis Society establish that once the diagnosis is confirmed and the treatment has been instituted, a visit must be scheduled every 4–6 weeks and, in stable patients, follow up must be made every 3–6 months [Ben-Zacharia and Lublin, 2009]. The visit schedule of patients with RRMS under treatment with immunomodulating agents is different in each Latin American country, largely due to administrative factors of their respective healthcare systems. Nonetheless, the panel stated that from a strictly medical standpoint a follow up with frequent visits is more beneficial to the patient, and the experts’ recommendation is that patients should be examined at least twice a year.

A relapse is the development of signs or symptoms that persist at least for 24 h. Further to the duration of relapses, it is important to determine their frequency, severity, and subsequent recovery [Freedman et al. 2004]. Relapse frequency must be considered in association with pretreatment patient history. Severity depends on individual factors, which must always be taken into account, and is difficult to evaluate. A resource that has proved effective to this extent is the Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score. Freedman and colleagues combined the criteria of relapse frequency and severity with subsequent recovery, and established an assessment model that classifies them into three different categories [Freedman et al. 2004]. The panel further discussed the convenience and need to take an MRI scan during relapses. In this respect, the experts’ opinion was divided between those who considered that an MRI was not necessary (on the grounds that it does not alter the treatment course during acute episodes and is too costly for healthcare systems), and those who favored its use to document relapses. The members of the panel agreed that it is absolutely necessary to obtain an MRI scan in cases of an attack in patients during treatment with natalizumab (Tysabri®) if there are new signs or symptoms suggestive of potential side effects associated with this drug, particularly PML. In other patients, the treating physician must evaluate the convenience of administering an MRI during relapses based on its severity, the patient’s response to corticosteroid treatment, and other special circumstances of the patient (e.g. if the patient is to be treated at their place of residence and this is distant from the center that coordinates treatment).

Disease progression may be evaluated based on clinical or paraclinical parameters, and represents another indicator of treatment failure. Progression may also be defined as a function of neuropsychological tests [Hirst et al. 2008], and it is advisable to perform them at the onset of the disease in order to have a baseline value for comparison purposes and an early assessment thereof. Although the most frequent scale to evaluate MS progression is the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [Kurtzke, 1983], the panel suggests administering the MS Functional Composite (MSF Composite) test if the center has professionals duly trained in its administration.

Experts also discussed the role of MRI as a method to document both relapses and disease progression, and referred to the importance of differentiating the transition to secondary progressive MS from treatment failure. They highlighted that regulatory authorities, and privately run and government-run healthcare plans of the Latin American countries have different requirements on the frequency of these tests. Irrespective of any such requirements, the administration of an MRI is considered mandatory in cases of suspected lack of efficacy. Routine follow-up MRI scans pose a significant financial burden on local healthcare systems and are not recommended [Rovira et al. 2010; Simon et al. 2006].

The experts discussed disability and cognitive impairment in patients with MS, as well as the most appropriate neuropsychological tests to assess them. The most frequently scale used to evaluate disability is the EDSS. However, in centers with trained staff, the panel recommends using the MSF Composite scale, which is a more accurate measurement of cognitive impairment. One of the difficulties that neurologists most frequently quote in relation to this scale is the administration of the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) that requires a series of complex calculations. This concern has led to a proposal to replace the PASAT with the Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

Latin American professionals have considerable experience in the assessment of cognitive impairment, which has acquired a greater relevance since the presence of axonal damage from disease onset was established. This assessment must be made by neuropsychologists, who should be part of the multidisciplinary team for the treatment of MS patients. Latin America has a number of neuropsychologists skilled in the application of Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery, which was validated in Spanish by Cáceres and colleagues [Cáceres et al. 2003], and the MS Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire developed by Benedict and colleagues [Benedict et al. 2004]. An expert group is currently working on the adaptation of cognitive assessment scales to Latin American idiosyncrasy. The recommendation of the expert panel is to perform an initial neuropsychological assessment with diagnosis and once a year thereafter with the above mentioned scales. Such initial assessment provides a baseline to evaluate progression. This recommendation is closely linked to the need to offer patients cognitive stimulation therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach to MS.

The experts recommended evaluating the quality of life of patients with MS as part of follow up, especially regarding patients’ perception of the disease. To such extent, panelists recommend the application of the MS quality-of-life scale, more specific than SF-36, at adequate intervals, as determined by the treating neurologist.

Conclusion

The expert panel was formed by representatives of the major Latin American countries and discussed the latest information on the diagnosis and treatment of MS through the healthcare systems of the countries in the region. The differential diagnoses highly prevalent in Latin America were also considered.

The analysis was based on the outcomes of the survey carried out among general neurologists, which provided an up-to-date perspective of the approach to the disease. However, the survey may be subject to some limitations. Some answers may not reflect actual clinical practice, but the correct behavior that neurologists believe should be followed in theory. This might be due to various factors, including the availability and coverage of the different treatments in each country, a lack of clinical expertise with MS patients among respondents, and response bias.

The experts made recommendations on the clinical and paraclinical diagnosis of MS, and advised healthcare systems to assign a longer consultation time for patients with MS (especially, for the first visit), which should be conducted by neurologists with broad experience in the management of the disease. The panelists established the recommended therapeutic approach based on the most reliable and recent evidence available, both regarding CIS and clinically defined forms of the disease. They likewise stated that all drugs approved for the treatment of MS should be available in the different countries and should be covered by healthcare systems.

The expert panel unanimously supported the creation of a permanent MS discussion forum, which would act as a fluent and open communication channel to discuss future clinical and therapeutic recommendations that may be useful to Latin American countries.

Footnotes

Gabriela Ortiz and Damián Vázquez collaborated in the preparation of the manuscript and their fees were paid with an unrestricted fund provided by Teva-Tuteur and Teva Pharmaceutical. This work was funded with an unrestricted grant from Teva-Tuteur and Teva Pharmaceutical covering the travel and accommodation of the panelists. Participants did not receive fees for their participation in the consensus meeting.

Dr Carrá is on the Advisory Board of Teva, Teva-Tuteur Argentina, and Biogen-Idec Argentina. Dr Correale is a board member of Merck-Serono Argentina, Biogen-Idec LATAM, and Merck-Serono LATAM. He has received reimbursement for developing educational presentations for Merck-Serono Argentina, Merck-Serono LATAM, Biogen-Idec Argentina, and Teva-Tuteur Argentina as well as professional travel/accommodation stipends. Dr Gabbai received honoraria for participating in meetings sponsored by Bayer Schering, Biogen-Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Teva. Dr Duriez has received fees for conferences from Stendhal and TEVA, as well as fees for projects of investigation for Bayer Schering and Merck Serono. Dr Macías-Islas received fees for being on the Advisory Board for Teva Neurosciences Mexico, Merck Serono, and Bayer Schering. Dr Vizcarra-Escobar has received compensation as a member of the Advisory Board for Stendhal, fees from Abbot and Pfizer for his participation at research projects, and fees from Pfizer and MEDCO for teaching conferences.

Dr García-Bonitto, Dr Vergara-Edwards and Dr Bolaña have nothing to disclose.

References

- Achiron A., Fredrikson S. (2009) Lessons from randomised direct comparative trials. J Neurol Sci 277(Suppl 1): S19–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Or A., Calabresi P.A., Arnold D., Markowitz C., Shafer S., Kasper L.H., et al. (2008) Rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 72-week, open-label, phase I trial. Ann Neurol 63: 395–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict R., Cox D., Thompson L., Foley F., Weinstock-Guttman B., Munschauer F. (2004) Reliable screening for neuropsychological impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 10:675–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zacharia A., Lublin F.D. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. 2009 Booklets series. Talking with your MS patients about difficult topics: Talking about initiating and adhering to treatment with injectable disease modifying agents. Available at: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/for-professionals/healthcare-professionals/publications/index.aspx (Last accessed on September 12, 2011).

- Bertolotto A. (2009) Implications of neutralising antibodies on therapeutic efficacy. J Neurol Sci 277(Suppl 1): S29–S32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres F., Vanotti S., Gold L., Rao S. Reconem Work Group (2003) The Reconem Study: cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis, a national survey in Argentina. Neurology 60, A 54 (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Cadavid D., Wolanksky L.J., Skurnick J., Lincoln J., Cheriyan K., Szczepanowski K., et al. (2009) Efficacy of treatment of MS with IFNβ-1b or glatiramer acetate by monthly brain MRI in the BECOME study. Neurology 72: 1976–1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerico M., Faggiano F., Palace J., Rice G., Tintoré M., Durelli L. (2008) Recombinant interferon beta or glatiramer acetate for delaying conversion of the first demyelinating event to multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD005278, DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005278.pub3 10.1002/14651858.CD005278.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J.A., Barkhof F., Comi G., Hartung H.P., Khatri B., Montalban X., et al. (2010) Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 362: 402–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles A.J., Compston D.A., Selmaj K.W., Lake S.L., Moran S., Margolin D.H., et al. (2008) Alemtuzumab vs. interferon beta-1a in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 359: 1786–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comi G., Filippi M., Barkhof F., Durelli L., Edan G., Fernández O., et al. (2001) Early Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Effect of early interferon treatment on conversion to definite multiple sclerosis: a randomised study. Lancet 357: 1576–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comi G., Martinelli V., Rodegher M., Moiola L., Bajenaru O., Carrá A., et al. (2009) PreCISe study group. Effect of glatiramer acetate on conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (PreCISe study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 374: 1503–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristiano E., Patrucco L., Rojas J.I. (2008) A systematic review of the epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in South America. Eur J Neurol 15: 1273–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristiano E., Patrucco L., Rojas J.I., Cáceres F., Carrá A., Correale J., et al. (2009) Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Buenos Aires, Argentina using the capture-recapture method. Eur J Neurol 16: 183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis T., Lublin F. (2008) Neurotherapeutics in multiple sclerosis: novel agents and emerging treatment strategies. Mt Sinai J Med 75: 157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz V., Antinao J.F., Quezada R.A., Barahona J. (2010) Hospital-based prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Chile. American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting, Toronto, poster P01.178 [Google Scholar]

- Durelli L., Cocito D., Riccio A. (1986) High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Neurology 36: 238–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi M., Rocca M.A., Arnold D.L., Bakshi R., Barkhof F., De Stefano N., et al. (2006) EFNS guidelines on the use of neuroimaging in the management of multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 13: 313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman M.S., Patry D.G., Grand’Maison F., Myles M.L., Paty D.W., Selchen D.H., Canadian M.S. (2004) Working Group Treatment optimization in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 31: 157–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcea O., Villa A., Cáceres F., Adoni T., Alegría M., Barbosa Thomas R., et al. (2009) Early treatment of multiple sclerosis: a Latin American Experts Meeting. Mult Scler 15(Suppl): S1–S12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin D.S., Hurwitz B., Noronha A. (2007) Neutralizing antibodies to interferon beta-1b are not associated with disease worsening in multiple sclerosis. J Int Med Res 35: 173–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser S.L., Waubant E., Arnold D.L., Vollmer T., Antel J., Fox R.J., et al. (2008) HERMES Trial Group B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 358: 676–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst C., Ingram G., Swingler R., Compston D.A., Pickersgill T., Robertson N.P. (2008) Change in disability in patients with multiple sclerosis: a 20-year prospective population-based analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79: 1137–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IFN-beta Multiple Sclerosis Study Group (1993) Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. I. Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 43: 655–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Working Group for Treatment Optimization in MS (2004) Treatment optimization in multiple sclerosis: report of an international consensus meeting. Eur J Neurol 11: 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L.D., Cookfair D.L., Rudick R.A., Herndon R.M., Richert J.R., Salazar A.M., et al. (1996) Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Ann Neurol 39: 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K.P., Brooks B.R., Cohen J.A., Ford C.C., Goldstein J., Lisak R.P., et al. (1995) Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology 45: 1268–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L., Freedman M.S., Polman C.H., Edan G., Hartung H.P., Miller D.H., et al. (2007) Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study. Lancet 370: 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L., Freedman M.S., Polman C.H., Edan G., Hartung H.P., Miller D.H., et al. (2009) Long-term effect of early treatment with interferon beta-1b after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: 5-year active treatment extension of the phase 3 BENEFIT trial. Lancet Neurol 8: 987–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L., Polman C.H., Freedman M.S., Edan G., Hartung H.P., Miller D.H., et al. (2006) Treatment with interferon beta-1b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology 67: 1242–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L., Radue E.W., O’Connor P., Polman C., Holfeld R., Calabresi P., et al. (2010) A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 362: 387–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan C., Kaplin A.I., Brodsky R.A., Drachman D.B., Jones R.J., Pham D.L., et al. (2008) Reduction of disease activity and disability with high-dose cyclophosphamide in patients with aggressive multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 65: 1044–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzke J.F. (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33: 1444–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetic G. (2008) Multiple sclerosis in Latin America. Int MS J 15: 6–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald W.I., Compston A., Edan G., Goodkin D., Hartung H.P., Lublin F.D., et al. (2001) Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: Guidelines from the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol 50: 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcon M., Gold L., Carrá A., Cáceres F., Correale J., Cristiano E., et al. (2008) Argentine Patagonia: prevalence and clinical features of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 14: 656–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo A., Rodrigues B., Bar-Or A. (2008) Beta interferons in clinically isolated syndromes: a meta-analysis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 66: 8–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikol D.D., Barkhof F., Chang P., Coyle P.K., Jeffery D.R., Schwid S.R., et al. (2008) Comparison of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a with glatiramer acetate in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (the Rebif vs Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing MS Disease [REGARD] study): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol 7: 903–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalban X., Tintoré M., Swanton J., Barkhof F., Filippi M., Frederiksen J., et al. (2010) MRI criteria for MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology 74: 427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor P., Filippi M., Arnason B., Comi G., Cook S., Goodin D., et al. (2009) (BEYOND Study Group) 250 µg or 500 µg interferon beta-1b versus 20 mg glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 8: 889–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda D.T., Mowry E.M., Beheshtian A., Waubant E., Baranzini S.E., Goodin D.S., et al. (2009) Incidental MRI anomalies suggestive of multiple sclerosis: the radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 72: 800–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman C.H., Reingold S.C., Banwell B., Clanet M., Cohen J.A., Filippi M., et al. (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald Criteria. Ann Neurol 69: 292–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman C.H., Reingold S.C., Edan G., Filippi M., Hartung H.P., Kappos L., et al. (2005) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”. Ann Neurol 58: 840–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poser C.M., Paty D.W., Scheinberg L., McDonald W.I., Davis F.A., Ebers G.C., et al. (1983) New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol 13: 227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMS Study Group (1998) Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneous in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Lancet 359: 1498–1504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann P., Traboulsee A., Devonshire V., Oger J. (2008) Escalating immunotherapy of multiple sclerosis: further options for escalating immunotherapy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 1: 181–192, DOI: 10.1177/1756285608098359 10.1177/1756285608098359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas J.I., Patrucco L., Cristiano E. (2010) Oligoclonal bands and MRI in clinically isolated syndromes: predicting conversion time to multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 257: 1188–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolak L.A. (2005) Differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. American Academy of Neurology Education Program, pp. 31–37 [Google Scholar]

- Rovira A., Tintoré M., Alvarez-Cermeño J.C., Izquierdo G., Prieto J.M. (2010) Recommendations for using and interpreting magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis. Neurologia 25: 248–265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher G.A., Beebe G., Kibler R.F., Kurland L.T., Kurtzke J.F., McDowell F., et al. (1965) Problems of experimental trials of therapy in multiple sclerosis: report by the Panel on the Evaluation of Experimental Trials of Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 122: 552–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J.H., Li D., Traboulsee A., Coyle P.K., Arnold D.L., Barkhof F., et al. (2006) Standardized MR imaging protocol for multiple sclerosis: Consortium of MS Centers consensus guidelines. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 27: 455–461 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanton J.K., Fernando K., Dalton C.M., Miszkiel K.A., Thompson A.J., Plant G.T., et al. (2006) Modification of MRI criteria for MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77: 830–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tintoré M., Rovira A., Río J., Tur C., Pelayo R., Nos C., et al. (2008) Do oligoclonal bands add information to MRI in first attacks of multiple sclerosis?. Neurology 70: 1079–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro J., Sarmiento O.L., Díaz del Castillo A., Satizábal C.L., Ramírez J.D., Montenegro A.C., et al. (2007) Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Bogotá, Colombia. Neuroepidemiology 28: 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Quintana M., Macías-Islas M.A., Rivera Olmos V., Lozano Zárate J. (2003) Esclerosis múltiple en México: un estudio multicéntrico. Rev Neurol 36: 1019–1022 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn D., Kaufman M., Montalban X., Wollmer T., Simon J., Elkins J., et al. (2010) Daclizumab in active relapsing multiple sclerosis (CHOICE study): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, add-on trial with interferon beta. Lancet Neurol 9: 381–390 [Epub 15 February 2010]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]