Abstract

Hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia (HAAA) is an uncommon but distinct variant of aplastic anaemia in which pancytopenia and bone marrow failure appears 2–3 months after an acute attack of hepatitis. Although bilateral vision loss may rarely be the initial presentation of aplastic anaemia, no such report is known in HAAA. Here the authors report such a case presenting with large premacular subhyaloid haemorrhages secondary to severe anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Anaemic hypoxic damage to the vessel wall together with increased cardiac output and low platelet counts are interacting causal factors in the development of bleeding. Though these haemorrhages are benign and usually improve spontaneously, the presence of blood may cause permanent macular changes before it resolves. Posterior hyaloidotomy enabled rapid resolution of premacular subhyaloid haemorrhage thereby restoring vision and preventing need for vitreo-retinal surgery. These patients should be advised to refrain from valsalva manoeuvres, ocular rubbing and vigorous exercise to prevent ocular morbidity.

Background

Aplastic anaemia is a rare disorder characterised by pancytopenia and a hypocellular bone marrow. The pathophysiology is believed to be idiopathic or immune-mediated with active destruction of haematopoietic stem cells, in the absence of infiltrative bone marrow disease.1

Ocular manifestations are common in aplastic anaemia with 70% of patients affected clinically in one or both eyes. Fundus findings include retinal and preretinal haemorrhages, Roth’s spots, vitreous haemorrhage, cotton wool spots and optic disc swelling. Retinal veins become dilated and tortuous, with the degree of retinal vein dilatation correlating with the severity of anaemia.2

Our patient presented with sudden onset of bilateral severe visual loss a few hours following a diagnostic bone marrow biopsy, during which he admitted he was holding his breath.

Severe anaemia results in diminished capillary oxygenation, producing increased vascular permeability and ultimately extravasation of blood and its products.3 A sudden increase in intravascular pressure caused by valsalva manoeuvre leads to the leakage of blood into the retina, this was aggravated by the associated thrombocytopenia.

Through this report we would like to highlight the importance of fundus examination in patients with aplastic anaemia to identify its harmful effects on retinal vasculature and the beneficial effects of neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser posterior hyaloidotomy for successful and rapid clearance of large premacular haemorrhages.

Case presentation

A 24-year-old Caucasian male was referred urgently by the haematologist with sudden onset of bilateral severe painless loss of vision noticed by the patient a few hours after a diagnostic bone marrow biopsy. The patient admitted that he was holding his breath during the entire procedure. He was under investigation by the haematologists for severe anaemia and thrombocytopenia following an acute attack of hepatitis 2 months ago.

Medical history – he first presented to the hospital 2 months ago with a 4-day history of jaundice, dark urine and pale stools. He was a university student and had no risk factors like intravenous drug use, high-risk sexual activity, recent travel, blood transfusion or exposure to toxins/drugs. Blood investigations done at the time showed profound transaminitis and hyperbilirubinaemia with alanine aminotransferase of 2768 U/l, aspartate aminotransferase 1778 U/l and total bilirubin of 270 micromol/l. Viral serology markers and for hepatitis (hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus (HDV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV)), cytomegalovirus, Epstein bar virus, transfusion transmitted virus, HIV and parvovirus B19 were negative classifying it as acute seronegative hepatitis. Liver biopsy showed acute lobular hepatitis with mild inflammation.

On eye examination, his best-corrected visual acuity in both eyes was hand movements. There was marked conjunctival pallor. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable with normal pupillary reactions and intra ocular pressure.

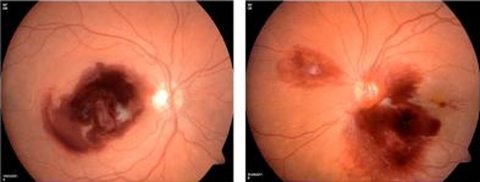

Dilated fundus examination revealed a healthy optic disc with large bilateral preretinal subhyaloid haemorrhages of about 5 disc diametres obscuring the macula, multiple scattered retinal haemorrhages and Roth’s spots (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Large bilateral preretinal subhyaloid haemorrhages obscuring the macula, multiple scattered retinal haemorrhages and Roth’s spots.

Investigations

Full blood counts and blood film showed severe pancytopenia with haemoglobin–5.8 g/dl, white cell count–2.7×109/l, neutrophil – 1.2×109 platelets count – 15×109/l and reticulocyte count – 17×109/l. Immunologic testing of peripheral blood showed an increase in CD8+ T lymphocytes indicating activation of cytotoxic T cells. Other tests including vitamin B12, folate, serum iron, ferritin and ceruloplasmin were normal excluding other causes of anaemia. Peripheral blood cytogenetics for Fanconi’s anaemia was negative. Autoimmune-disease evaluation like antinuclear antibody and anti-dsDNA for evidence of collagen-vascular disease was negative. Fluorescent in situ hybridisation did not show any deletions of 5 and 7 chromosomes thereby excluding myelodysplastic syndrome. A CT scan of the abdomen was normal with no signs of organomegaly or lymphadenopathy. A diagnostic bone marrow biopsy confirmed aplastic anaemia (<5% cellularity) and the haematologists made a diagnosis of hepatitis associated aplastic anaemia.

Treatment

The patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungal agents to avoid secondary infection due to severe neutropenia. He was started on immunosuppressive therapy, as he did not have an HLA-matched related donor.

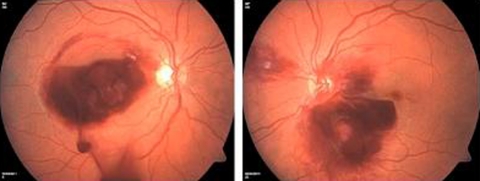

After stabilising his haematological status with multiple red blood cell (RBC) and platelet transfusions, he underwent Nd:YAG laser posterior hyaloidotomy to both eyes. The beam was focused on the posterior hyaloid membrane and a single burst of 5 mJ was used after which the blood immediately began to drain from the preretinal haemorrhage into the vitreous cavity (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Blood draining from the preretinal haemorrhages into the vitreous cavity immediately following a single burst of Nd:YAG laser.

Outcome and follow-up

Dilated fundus examination after 2 days showed blood to be draining from the preretinal haemorrhages into the vitreous and therefore no further Nd:YAG laser was indicated. At 1 month follow-up, his vision in the right eye–6/9 and left eye – 6/12.

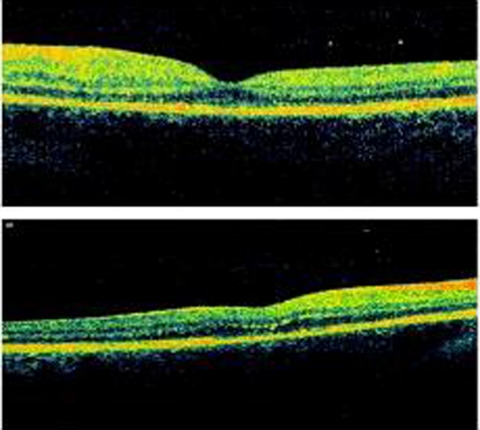

Fundus photos showed small residual subretinal fibrosis and some residual haemorrhages outside the macula (figure 3). The blood in the vitreous had resolved spontaneously over a period of 1 month. Optical coherence tomography of both eyes at 1 month post Nd:YAG treatment showed a healthy macula confirming that preretinal subhyaloid macular haemorrhages had not affected the macula (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Fundus photos at 1-month follow-up showing small residual subretinal fibrosis and some residual haemorrhages outside the macula. The blood in the vitreous had resolved spontaneously.

Figure 4.

OCT scan of both eyes at 1-month post Nd:YAG treatment showing a healthy macula (above right and below left eye).

There were no complications as a result of the laser treatment and his vision improved to 6/6 in right eye and 6/9 in left eye at the last follow-up visit at 3 months.

He was under regular follow-up by the haematologists and was showing consistent, albeit incomplete recovery with immunosuppressive therapy.

Discussion

Aplastic anaemia is a life-threatening condition associated with a hypoplastic ‘fatty or empty’ bone marrow and global dyshematopoiesis. It can be inherited but it is more commonly acquired. The pathophysiology is believed to be idiopathic or in most cases, aplastic anaemia behaves as an immune-mediated disease. Cellular and molecular pathways have been mapped in some detail for both effector (T lymphocyte) and target (haematopoietic stem and progenitor) cells.1 4 The abnormal immune response may be elicited by environmental exposures to chemicals (benzene), drugs (chloramphenicol, penicillamine, gold, etc.), viral infections, autoimmune diseases, endogenous antigens generated by genetically altered bone marrow cells and even pregnancy.4 5 A small fraction of genes involved in pancytopenia have been represented by the congenital bone marrow failure syndromes like Fanconi’s anaemia, dyskeratosis congenita and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome.6

Hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia is a distinct variant of acquired aplastic anaemia that usually follows an episode of seronegative hepatitis leading to bone marrow failure and pancytopenia.1 4 This syndrome shows a stereotypical pattern; most often affecting young males, the hepatitis generally follows a benign course, but the onset of aplastic anemia 2 to 3 months later can be explosive and is usually fatal if untreated.

The aetiology of this syndrome has been attributed to various hepatitis and non-hepatitis viruses. Several hepatitis viruses such as HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV and hepatitis G virus and viruses other than the hepatitis viruses such as parvovirus B19, cytomegalovirus, Epstein bar virus, transfusion transmitted virus and non-A–E hepatitis virus (unknown viruses) has also been documented to develop the syndrome. However, in a majority of cases, the principal cause of hepatitis remains unknown and despite intensive and sophisticated efforts, an infectious agent has yet to be identified.4 7 8

Several characteristics of this syndrome including clinical features, severe imbalance of the T cell immune system and response to immunosuppressive therapy suggest an immune-mediated mechanism to be implicated in its pathogenesis.9 No association of hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia has been found with blood transfusions, drugs and toxins. Besides hepatitis, non-hepatitis viruses and immunological mechanisms as causative agents of the disorder, telomerase mutation, a genetic factor has also been predisposed for the development of aplastic anaemia.6

As with our patient the hepatitis was clinically indistinguishable from a typical viral hepatitis, but no specific cause could be identified.

Anaemia produces retinal ischemia when it is sudden or severe so that auto regulatory adaptation cannot occur. Retinal manifestations tend to localise to the posterior pole and often manifest when the haemoglobin level is lower than 7 g/100ml. Interestingly, children with a similar severity of anaemia seem to be more resistant to the development of anaemic retinopathy than adults. Preretinal and vitreous haemorrhages occur almost exclusively in patients with combined anaemia and thrombocytopenia.10 The other common causes of subhyaloid or macular haemorrhage are valsalva retinopathy and Terson syndrome. In addition, such haemorrhages may occur secondary to vascular diseases such as arteriosclerosis, hypertension, retinal artery or vein occlusion, diabetic retinopathy, retinal macroaneurysm, chorioretinitis, blood disorders, shaken baby syndrome, age-related macular degeneration and can also occur spontaneously or as a result of blunt trauma.11

Premacular subhyaloid haemorrhage produces sudden, profound visual loss that may be prolonged if untreated. Spontaneous resorption of blood entrapped in the subhyaloid space may take months and result in permanent visual impairment due to pigmentary macular changes, formation of epiretinal membranes and toxic damage to the retina from prolonged contact with haemoglobin and iron.12 13

Different techniques have been used to treat premacular haemorrhage including pars plana deep vitrectomy and pneumatic displacement of haemorrhage by intravitreal injection of gas and tissue plasminogen activator.14

The application of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for drainage of a premacular subhyaloid haemorrhage into the vitreous was first described by Faulborn15 in 1988 for an eye with diabetic retinopathy. Nd:YAG laser treatment creates a focal opening enabling drainage of entrapped premacular subhyaloid blood into the vitreous gel. Hence, the obstructed macular area is cleared and absorption of blood cells may be facilitated. It results in rapid visual recovery and has good outcomes especially in patients with valsalva retinopathy.12 13 This is particularly important in young, economically active patients whose visual requirements might indicate early treatment. However, the pretreatment duration of haemorrhage is of prognostic importance. Nd:YAG laser is best done within 4 weeks, as with time the haemorrhage turns yellowish due to degeneration of haemoglobin and the clotted blood is unlikely to drain into the vitreous gel despite successful perforation.13

Although rare, reported complications with Nd:YAG laser include epiretinal membrane formation with internal limiting membrane wrinkling,16 macular hole formation and retinal detachment from pre-existing retinal breaks in a myopic patient.12

Learning points.

-

▶

In severe anaemia the retinal endothelial cell integrity is jeopardised by ischemia, vessel wall dilatation (stretch) and increased blood flow (shear stress) allowing easier seepage of RBC’s through interendothelial junctions when platelets that act as endothelial ‘plugs’ are deficient.

-

▶

Increasing intravascular pressure by oculo-digital massage or valsalva manoeuvres can enhance the leakage of blood into the retina. These patients should therefore be advised to refrain from such activities to prevent ocular morbidity.

-

▶

Co-ordination of medical and surgical care with the haematology service is advisable to stabilise haematologic parameters prior to undertaking a vitreo-retinal procedure.

-

▶

Nd:YAG laser posterior hyaloidotomy is a useful outpatient procedure for successful clearance of large premacular haemorrhages that offers patients rapid recovery of visual acuity and the avoidance of more invasive intraocular surgery. This is particularly important for patients with poor vision in their fellow eye and patients requiring rapid visual rehabilitation to be able to continue working.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Gonzalez-Casas R, Garcia-Buey L, Jones EA, et al. Systematic review: hepatitis-associated aplastic anaemia–a syndrome associated with abnormal immunological function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:436–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aisen ML, Bacon BR, Goodman AM, et al. Retinal abnormalities associated with anemia. Arch Ophthalmol 1983;101:1049–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duke-Elder S, Dobree JH. The blood diseases. In: Duke-Elder S, ed. System of Ophthalmology. CV Mosby: St Louis; 1967:373–407 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young NS. Pathophysiologic mechanisms in acquired aplastic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006:72–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsh JC, Ball SE, Darbyshire P, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acquired aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 2003;123:782–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rauff B, Idrees M, Shah SA, et al. Hepatitis associated aplastic anemia: a review. Virol J 2011;8:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safadi R, Or R, Ilan Y, et al. Lack of known hepatitis virus in hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia and outcome after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001;27:183–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown KE, Tisdale J, Barrett AJ, et al. Hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1059–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cudillo L. Aplastica anemia and viral hepatitis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2009;1:e2009026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mansour AM, Salti HI, Han DP, et al. Ocular findings in aplastic anemia. Ophthalmologica 2000;214:399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mennel S. Subhyaloidal and macular haemorrhage: localisation and treatment strategies. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:850–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rennie CA, Newman DK, Snead MP, et al. Nd:YAG laser treatment for premacular subhyaloid haemorrhage. Eye (Lond) 2001;15(Pt 4):519–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulbig MW, Mangouritsas G, Rothbacher HH, et al. Long-term results after drainage of premacular subhyaloid hemorrhage into the vitreous with a pulsed Nd:YAG laser. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:1465–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nili-Ahmadabadi M, Ali-Reza L, Karkhaneh R, et al. Nd:YAG laser application in premacular subyaloid hemorrhage. Arch Iranian Med 2004;7:206–9 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faulborn J. Behandlung einer diabetischen praemaculaeren Blutung mit dem Qswitched Neodym:YAG laser. Spektrum Augenheilkd 1988;2:33–5 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwok AK, Lai TY, Chan NR. Epiretinal membrane formation with internal limiting membrane wrinkling after Nd:YAG laser membranotomy in valsalva retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:763–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]