Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Intractable haemorrhage after endoscopic surgery, including transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP), is uncommon but a significant and life-threatening problem. The knowledge and technical experience to deal with this complication may not be wide-spread among urologists and trainees. We describe our series of TURPs and PVPs and the incidence of postoperative bleeding requiring intervention.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed 437 TURPs and 590 PVPs over 3 years in our institution. We describe the conservative, endoscopic and open prostatic packing techniques used for patients who experienced postoperative bleeding.

RESULTS

Of 437 TURPs, 19 required endoscopic intervention for postoperative bleeding. Of 590 PVPs, two patients were successfully managed endoscopically for delayed haemorrhage at 7 and 13 days post-surgery, respectively. In one TURP and one PVP patient, endoscopic management was insufficient to control postoperative haemorrhage and open exploration and packing of the prostatic cavity was performed.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant bleeding after endoscopic prostatic surgery is still a potentially life-threatening complication. Prophylactic measures have been employed to reduce peri-operative bleeding but persistent bleeding post-endoscopic prostatic surgery should be treated promptly to prevent the risk of rapid deterioration. We demonstrated that the technique of open prostate packing may be life-saving.

Keywords: TURP, PVP, Packing of the prostate, Haemorrhage

There are several techniques of transurethral prostatic surgery including the traditional transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and newer techniques including holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP), Green-light laser photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP) and the Gyrus bipolar system. The number of TURPs is falling1 and there is no doubt that newer techniques are being accepted as established alternatives. Bleeding is one of the main complications after any modality of endoscopic prostatectomy, including TURP. The incidence of blood loss requiring transfusion is reported to be 0.4–7.1 %,2,3 with rates declining with evolving technology despite an increasingly aged population having prostatic surgery.

The experience of surgeons dealing with troublesome bleeding is now, therefore, much less. The conservative, resuscitative and endoscopic measures to deal with bleeding are well established and understood. However, there are occasions when this is not sufficient to stop what may be life-threatening haemorrhage and many surgeons may now be unfamiliar with the surgical technique of packing the prostatic cavity to arrest bleeding when other measures have failed. In this paper, we have reviewed all TURP and PVP procedures over a 3-year period and identified those patients who required surgical intervention postoperatively to arrest continuing haemorrhage and in particular describe open packing of the prostate.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed a 3-year period where 437 TURPs and 590 PVPs were performed for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and for urinary retention in our institution. Of patients who underwent TURP, 19 needed a cys-toscopy in the immediate postoperative period for persistent bleeding despite conservative measures such as catheter traction and manual bladder washouts. Two patients who underwent PVP required cystoscopy for delayed haemorrhage. In one TURP and one PVP patient, cystoscopy, endo-scopic bladder washout and coagulation of the bleeding vessels were insufficient to control the haemorrhage and subsequent open exploration and packing of the prostatic cavity was undertaken.

Resuscitation and return to theatre

All patients with postoperative bleeding were initially managed with saline bladder washouts followed by continuous irrigation and manual traction of the three-way catheter with 30 ml in the catheter balloon. The senior urologist was informed early; if, after a period of conservative treatment, the patient was still experiencing uncontrolled bleeding then the following measures were taken with the aim of returning to theatre promptly to stop the bleeding and prevent deterioration of the patient's condition. During and after conservative measures, full continuous external monitoring was employed with high flow oxygen. Venous blood was sent for haemoglobin, electrolytes, clotting studies and cross match and the haematology team informed of the potential need for blood products. An ECG was obtained and broad-spectrum antibiotics commenced. The anaesthetic, HDU and theatre staff informed of a potential emergency procedure. The patient was consented for further endoscopic intervention and also for laparotomy should packing of the prostate be required. Following resuscitation with fluids and blood products as the situation dictated, the patients were anaesthetised and a cystoscopy performed. Using a resectoscope and Elik evacuators, any clot within the bladder was removed. Bleeding points were identified and diathermied and rigorous fluid balance was ensured to identify any risk of bladder perforation. If progress was not being made at any point of the procedure the decision was taken to perform an open packing of the prostate by a consultant urologist.

Prostate packing technique

The patient was positioned supine and the abdomen opened by a lower midline incision. The bladder was identified and opened between two stay sutures. Blood clots were evacuated and the prostatic fossa inspected for any obvious bleeding points that were diathermied or secured by ligatures.

A 22-Fr, three-way urethral catheter was inserted into the bladder, via the urethra, with the balloon deflated at this stage (Fig. 1). The prostatic fossa was then tightly packed with ribbon gauze (enough rolls of 1–2 inches width), the catheter balloon inflated and traction applied. This holds the gauze in place and tamponades the prostatic cavity (Fig. 2). A 22-Fr three-way suprapubic catheter was placed and the cystotomy closed with 2/0 Vicryl sutures in two layers. The pelvic cavity around the bladder was packed with abdominal packs (18 × 18 inches) to keep the bladder collapsed and prevent it from filling with blood from prostatic bleeding to reduce the chance of the procedure failing in a patient who may now be seriously ill. The abdomen closed with one vicryl mass closure and running stitch to the skin. Continuous normal saline bladder irrigation through the suprapubic catheter to the urethral catheter was commenced immediately postoperatively.

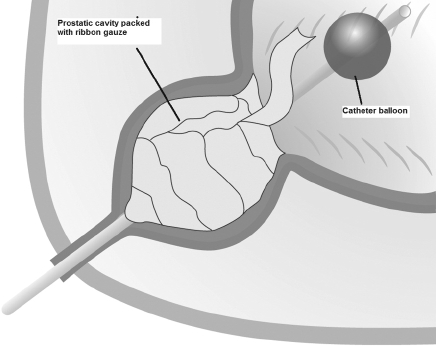

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation ribbon gauze packed into the prostatic fossa and a three–way catheter with balloon inflated but not under traction within the bladder.

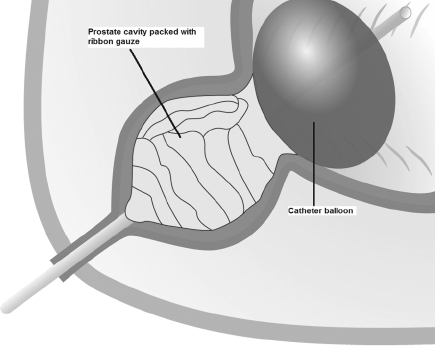

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic representation ribbon gauze packed into the prostatic fossa and a three–way catheter with balloon inflated now under traction compressing the gauze to effect haemostasis.

After 36–48 h, following patient stabilisation, the abdomen, bladder and prostatic cavity were re-explored and all the packs slowly removed. The bladder was closed, after ensuring complete haemostasis, in two layers leaving the two catheters in situ. The abdomen was closed as previously described. The suprapubic catheter was removed after 72 h and the urethral catheter after 7 days. Following an uneventful recovery, both patients were discharged and subsequently attended regular assessment of LUTS, including flow studies and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) evaluation.

Results

Of the 437 TURPs performed, 19 required further endoscopic intervention for persistent postoperative bleeding of which one required open exploration and packing. Of 590 PVPs performed, one required open exploration and packing and two patients were successfully managed with cystoscopy and diathermy for delayed haemorrhage at 7 and 13 days post-surgery, respectively.

In both patients who required packing, bleeding was effectively controlled by this technique with a subsequent uneventful recovery. Long-term follow-up of 16 months and 55 months (for the PVP and TURP patients, respectively) demonstrate good flow studies with satisfactory IPSS scores.

Discussion

Significant bleeding after endoscopic prostatic surgery, although increasingly less common,4 is still a potentially life-threatening complication. However, transurethral resection of larger prostates is associated with a higher incidence of bleeding requiring transfusion, with the weight of resected tissue being the most important measureable factor in determining blood loss.5 In one series, 85% of patients needed transfusion when resection exceeded 80 g of prostate.6

Various prophylactic measures have been employed to reduce peri-operative bleeding including cessation of anticoagulant medical therapies such as aspirin products and warfarin. Warfarin therapy at the time of TURP has been shown to result in transfusion rates around 30%7 and can be successfully and safely substituted with intravenous heparin for TURP in high-risk patients.8 The omission of aspirin prior to TURP shows a wide variation in clinical practice with 62% of UK consultant urologists requiring aspirin to be stopped prior to TURP and 38% not.9 This perhaps is a reflection of the literature with some evidence suggesting aspirin use is associated with a significant increase in postoperative blood loss after TURP10 and others who report blood loss not being enhanced with aspirin use.11

More contemporary strategies for reducing peri-operative blood loss are the use of 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors such as Finasteride and Dutasteride. Recent evidence has demonstrated a 4-week course of Finasteride, pre-opera-tively, results in a reduction in the total amount of bleeding and the amount of bleeding per gram of resected tissue at TURP.12 Similar conclusions have been drawn from shorter courses of only 2-week Finasteride13 but have yet to be clearly demonstrated with Dutasteride.14

Persistent bleeding post-endoscopic prostatic surgery should be treated promptly to prevent deterioration of the patient and their clinical parameters. Management should be undertaken in a step-wise fashion starting with conservative measures; however, if these are not successful, early and appropriate return to theatre in conjunction with full resuscitation with the patient fully aware and consented that laparotomy and prostatic packing may be required. Applying catheter traction,15 effective bladder irrigation and bladder washout to evacuate the clots can control bleeding. Despite these measures, a minority of patients continue to bleed requiring further intervention such as cystoscopy bladder washout and further diathermy of any bleeding vessel that, if unsuccessful, is an indication for packing the prostate.

The use of temporary packing to obtain haemostasis is a practiced adjunct to surgical procedures in the pelvis16 including urological procedures such as open radical and Millin's prostatectomies and cystectomies, and has become an acceptable approach to control haemorrhage from hepatic injuries.17 This technique of packing the prostate has been demonstrated to be an effective method of controlling bleeding even in adverse circumstances with the absence of any direct long-term complications. Alternative methods of haemostasis include selective embolisation of the iliac vessels under radiological control18 and open ligation of one or both iliac arteries.19 However, these procedures have their disadvantages, such as the availability of interventional radiology for embolisation and, in both, the inability to control venous bleeding, and the risk of subsequent gluteal claudication and vasculogenic impotence. Our series demonstrated that the technique of open prostate packing can rapidly and efficiently control the haemorrhage and arrest a potentially life-threatening complication without any demonstrable morbidity and with good lower urinary tract symptom outcome at follow-up. This technique does, however, necessitate the need for a second exploration under general anaesthetic to remove the packs; however, this is of limited significance compared to the potential life-threatening risk of haemorrhage following prostatic surgery.

Conclusions

The incidence of postoperative haemorrhage associated with endoscopic prostatic surgery in recent years has reduced but there has also been a concomitant reduction in the number of TURPs performed and associated experience of the surgeon in how to manage uncontrollable postoperative haemorrhage endoscopically and open. We have presented a series of patients of which a minority presented with severe bleeding post TURP and PVP who have been managed safely and effectively with conservative, endoscopic and, where required, open exploration and packing. It is important not to delay the decision to pack the prostate to prevent deterioration of the patient and the increased risks of complications that may be life-threatening. With the development of endoscopic and minimally invasive prostat-ic surgery, there may be a reduced need for packing the prostate; however, all surgeons should be aware of this technique and its critical role in arresting severe or catastrophic bleeding following endoscopic prostatic surgery.

References

- 1.Wilson JR, Urwin GH, Stower MJ. The changing practice of transurethral prostatectomy: a comparison of cases performed in 1990 and 2000. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:428–31. doi: 10.1308/147870804731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Writing Committee, the American Urological Association. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. Cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluation 3,885 patients. J Urol. 1989;141:243–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rassweiler J, Teber D, Kuntz R, Hofmann R. Complications of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) – incidence, management and prevention. Eur Urol. 2006;50:969–79. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendt-Nordahl G, Bucher B, Häcker A, Knoll T, Alken P, Michel MS. Improvement in mortality and morbidity in transurethral resection of the prostate over 17 years in a single centre. J Endourol. 2007;21:1081–7. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirollos MM, Campbell N. Factors influencing blood loss in transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): auditing TURP. Br J Urol. 1997;80:111–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal M, Palmer JH, Mufti GR. Transurethral resection fora large prostateis it safe? Br J Urol. 1993;72:318–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parr NJ, Loh CS, Desmond AD. Transurethral resection of the prostate and bladder tumour without withdrawal of warfarin therapy. Br J Urol. 1989;64:623–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1989.tb05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakravarti A, MacDermott S. Transurethral resection of the prostate in the anti-coagulated patient. Br J Urol. 1998;81:520–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enver MK, Hoh I, Chinegwundoh FI. The management of aspirin in transurethral prostatectomy: current practice in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:280–3. doi: 10.1308/003588406X95084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen JD, Holm-Nielsen A, Jespersen J, Vinther CC, Settgast IW, Gram J. The effect of low dose acetylsalicylic acid on bleeding after transurethral prostatec tomy – a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2000;34:194–8. doi: 10.1080/003655900750016580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ala-Opas MY, Gronlund SS. Blood loss in long-term aspirin users undergoing transurethral prostatectomy. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1996;30:203–6. doi: 10.3109/00365599609181300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozdal OL, Ozden C, Benli K, Gokkaya S, Bulut S, Memis A. Effect of short-term finasteride therapy on preoperative bleeding in patients who were candidates for transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P): a randomized controlled study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:215–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donohue JF, Sharma H, Abraham R, Natalwala S, Thomas DR, Foster MC. Transurethral prostate resection and bleeding: a randomised, placebo controlled trial of role of finasteride for decreasing operative blood loss. J Urol. 2002;168:2024–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn RG, Fagerstrom T, Tammela TL, Van Vierssen Trip O, Beisland HO, et al. Blood loss and postoperative complications associated with transurethral resection of the prostate after pretreatment with dutasteride. BJU Int. 2007;99:587–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker EM, Bera S, Faiz M. Does catheter traction reduce post trans-urethral resection blood loss? Br J Urol. 1995;75:614–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mireku-Boateng AO, Jacjson AG. Prostate fossa packing: a simple, quick and effective method of achieving haemostasis in suprapubic prostatectomy. Urol Int. 2005;74:180–2. doi: 10.1159/000083291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Therapeutic perihepatic packing in complex liver trauma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:43–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appleton DS, Sibley GN, Doyle PT. Internal iliac artery embolisation for the control for the control of severe bladder and prostate haemorrhage. Br J Urol. 1988;61:45–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb09160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao ZM. Ligation of the internal iliac arteries in 110 cases as a haemostatic procedure during suprapubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1980;124:578. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]