Abstract

α6* (asterisk indicates the presence of additional subunits) nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are broadly implicated in catecholamine-dependent disorders that involve attention, motor movement, and nicotine self-administration. Different molecular forms of α6 nAChRs mediate catecholamine release, but receptor differentiation is greatly hampered by a paucity of subtype selective ligands. α-Conotoxins are nAChR-targeted peptides used by Conus species to incapacitate prey. We hypothesized that distinct conotoxin-binding kinetics could be exploited to develop a series of selective probes to enable study of native receptor subtypes. Proline6 of α-conotoxin BuIA was found to be critical for nAChR selectivity; substitution of proline6 with 4-hydroyxproline increased the IC50 by 2800-fold at α6/α3β2β3 but only by 6-fold at α6/α3β4 nAChRs (to 1300 and 12 nM, respectively). We used conotoxin probes together with subunit-null mice to interrogate nAChR subtypes that modulate hippocampal norepinephrine release. Release was abolished in α6-null mutant mice. α-Conotoxin BuIA[T5A;P6O] partially blocked norepinephrine release in wild-type controls but failed to block release in β4−/− mice. In contrast, BuIA[T5A;P6O] failed to block dopamine release in the wild-type striatum known to contain α6β2* nAChRs. BuIA[T5A;P6O] is a novel ligand for distinguishing between closely related α6* nAChRs; α6β4* nAChRs modulate norepinephrine release in hippocampus but not dopamine release in striatum.—Azam, L., Maskos, U., Changeux, J.-P., Dowell, C. D., Christensen, S., De Biasi, M., McIntosh, J. M. α-Conotoxin BuIA[T5A;P6O]: a novel ligand that discriminates between α6β4 and α6β2 nAChRs and blocks nicotine-stimulated norepinephrine release.

Keywords: nicotinic, α6, Conus, hydroxyproline, hippocampus

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are ligand-gated ion channels found throughout the nervous system and in non-neuronal tissue. Multiple nAChR subunits (α1–α10, β1–β4) have been cloned. These subunits combine in various combinations to form pentameric assemblies (1–3). The subunit composition of the receptor confers unique pharmacological and biophysical properties to the particular nAChR subtype (4, 5). In situ hybridization and immunoprecipitation studies have indicated that nAChR subunits are not randomly distributed but instead have distinct anatomical expression patterns (3, 6–8). The α6 subunit has gained increasing attention because of its putative role in nicotine reinforcement and addiction (9, 10), changes in expression on chronic nicotine administration (11–13), and its selective down-regulation in Parkinson's disease (14–17). Both functional and immunoprecipitation studies have indicated that the native α6 subunit can form functional receptors when combined with β2 or β4 subunits (2, 18). In many regions, including brain and retina, all three subunits are colocalized, and therefore it has been difficult to functionally differentiate α6β2* (asterisk indicates the presence of additional subunits) and α6β4* nAChRs based solely on anatomical localization of subunits.

Thus, in light of studies suggesting the pathophysiological importance of the α6* nAChRs, it is imperative to distinguish the role of α6β2* nAChRs from those of other α6-containing (i.e., α6β4*) nAChRs. α-Conotoxins (α-CTxs) are small peptides that potently and selectively block nAChRs (19, 20). Some α-CTxs are highly selective for individual nAChR subtypes. These toxins include α-CTx MI that blocks the neuromuscular α1β1δγ/ε subtype, α-CTx RgIA that blocks the α9α10 nAChR, and α-CTx ArIB[V11L;V16D] that blocks the α7 subtype (21–23). Analogs of α-CTx MII selectively block α6-containing nAChRs (24). At present, however, there are no ligands that potently block α6β4* without also binding α6β2* nAChRs. In this study we synthesized analogs of α-CTx BuIA and used structure/function insights to create an analog of α-CTx BuIA that is selective for α6β4 nAChRs. We then used this new ligand to probe the functional roles of α6β2- and α6β4-containing nAChRs in nicotine-evoked norepinephrine (NE) release in hippocampus.

Nicotine-evoked dopamine (DA) release in mouse striatum has been extensively characterized previously with subtype selective ligands, antibodies, and nAChR receptor subunit-null mice (25–30). Five subtypes of nAChRs have been identified on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Three of these contain the α6 subunit (α4α6β2β3, α6β2β3, and α6β2); the other two subtypes are α4β2 and α4α5β2. Note that none of these subtypes contain the β4 subunit. In comparison, nicotine evoked NE in mouse hippocampus has received little attention. In a previous study, we showed that α-CTx MII and α-CTx PIA block [3H]NE release, indicating the presence of the α6 subunit in the responsible nAChR(s). Results with β2 and β4 subunit-deficient mice and kinetic experiments with unmodified α-CTx BuIA led us to propose that that an α6β4* nAChR subtype underlies a portion of nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release (31). In the present study we used the new α-CTx BuIA analog, which distinguishes between α6β4 and α6β2 nAChRs, together with α6 and β4 nAChR-knockout mice, to further assess the nAChR subtypes that modulate [3H]NE release. The results indicate that different molecular forms of α6-containing nAChRs modulate NE and DA release from hippocampus and striatum, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Acetylcholine chloride, (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate, pargyline HCl, ascorbic acid, atropine, and BSA were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA). [3H]NE (norepinephrine, levo-[ring-2,5,6-3H]; 52–53 Ci/mmol) and [3H]DA (dihydroxyphenylethylamine, 3,4-[7-3H(N)]) were from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA, USA). EcoLume scintillation cocktail was from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA). α-Conotoxins were synthesized as described previously (24, 32). Clones of nAChR subunits were kindly provided by the following individuals: S. Heinemann (Salk Institute, San Diego, CA, USA), rat α2-α7; Chuck Luetje (University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA), rat β2 and β3 subunits in the high-expressing pGEMHE vector; and Jerry Stitzel (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA), mouse nAChRs. Because the α6 subunit does not readily form functional receptors, we used a surrogate formed by splicing the N-terminal extracellular ligand-binding region of the α6 subunit with the remaining fragment of the α3 subunit as described previously (24).

cRNA preparation and injection

Capped cRNA for the various subunits were made using the mMessage mMachine in vitro transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) after linearization of the plasmid. The cRNA was purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The concentration of cRNA was determined by absorbance at 260 nm. Fifty to 150 nl of cRNA mixture was injected into each Xenopus oocyte (equivalent to 25–30 ng of cRNA for each subunit) with a Drummond microdispenser (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA, USA), as described previously (32), and incubated at 17°C. Oocytes were injected within 1–2 d of harvesting, and recordings were made 2–4 d after injection.

Voltage-clamp recording

Oocytes were voltage-clamped at −70 mV and exposed to ACh and peptide as described previously (33). In brief, the oocyte chamber, consisting of a cylindrical well (∼30 μl in volume), was gravity perfused at a rate of ∼2 ml/min with ND-96 buffer (96.0 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.1–7.5) containing 1 μM atropine (except for α7 and α9α10 nAChRs) and 0.1 mg/ml BSA. The oocyte was subjected 1×/min to a 1-s pulse of 100 μM ACh. This dose of ACh has been shown to evoke a substantial and consistent response for all subtypes expressed in oocytes. For screening of receptor chimeras and mutants for toxin concentrations of 1 μM and lower, once a stable baseline was achieved, either ND-96 alone or ND-96 containing various concentrations of the α-conotoxins was perfusion-applied, during which 1-s pulses of 100 μM ACh were applied every minute until a constant level of block was achieved. For toxin concentrations of 10 μM and higher, the buffer flow was stopped and the toxin bath was applied and allowed to incubate with the oocyte for 5 min (static bath application), after which the ACh pulse was resumed. For the toxin kinetic studies, once a stable level of inhibition was achieved on toxin application, the toxin solution was switched to ND-96 buffer, and ACh pulses were recorded until the response reached the levels seen before toxin application (baseline).

Neurotransmitter release assay

Tissue preparation

For the [3H]NE release experiments, male and female C57BL/6J mouse pups (both wild type and knockout) between 14 and 20 d old were used. We used pups for these experiments because, as previously shown (31), adult mice exhibit little nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release from synaptosomal preparations. For the [3H]DA release experiments, C57BL/6J adult male mice older than 50 d were used. The α6−/− mice (34) were backcrossed >14 generations on a C57BL/6J background. The β4−/− mice (35) were backcrossed 8–10 generations on a C57BL/6J background. The animals were decapitated, and brains were quickly removed. This procedure was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah and is consistent with federal guidelines. Synaptosomes were prepared essentially as described previously (36). In brief, the entire hippocampus or striatum was quickly dissected on ice and placed in ice-cold 0.32 M sucrose buffer, pH 7.4–7.6. The dissected tissue was homogenized by 14 gentle up and down strokes, followed by centrifugation at 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting P2 pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of Krebs-HEPES buffer (superfusion buffer) with composition of 128 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM MgSO4, 3.2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES, and 10 mM glucose and supplemented with 1 mM ascorbic acid and 0.1 mM pargyline. The synaptosomes were incubated for 10 min at 37°C to equilibrate with the superfusion buffer, followed by another 10-min incubation with 0.13 μM [3H]NE (specific activity 52–53 Ci/mmol) or 0.12 μM [3H]DA (specific activity 28–30 Ci/mmol) at 37°C. The synaptosomes were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 5 min to get rid of excess radiolabeled NE or DA. The pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of superfusion buffer, and 1 ml was transferred into each of four conical tubes containing 3 ml of superfusion buffer and subsequently loaded into the superfusion chambers containing 13-mm-diameter A/E glass fiber filters (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). One tube (4 ml total volume) contained enough synaptosomes for 6 chambers of the superfusion apparatus.

Superfusion

The superfusion system had 12 identical channels and was set up as described previously (36). Once synaptosomes were loaded into the superfusion apparatus, they were washed for 20 min with either superfusion buffer alone or buffer plus varying concentrations of the toxins, at a rate of 0.5 ml/min. After the wash period, 2-min fractions were collected in 6-ml polypropylene vials containing 4 ml of EcoLume scintillation cocktail. At the end of the third 2-min fraction, a 1-min pulse of 10 μM ([3H]DA release) or 100 μM ([3H]NE release) nicotine or nicotine plus toxin was applied, followed by five 2-min washes with superfusion buffer alone. At the end of the superfusion, filters containing the synaptosomes were taken out and placed directly in vials containing 4 ml of EcoLume to determine total [3H]NE or [3H]DA uptake. Radioactivity collected in each fraction was quantitated by liquid scintillation spectroscopy, with a Beckman 5801 liquid scintillation counter, tritium efficiency ∼50%.

Data analysis

Throughout this article, tritium release is presumed to correspond directly to amounts of radiolabeled transmitter release, as it has been shown previously that tritium released by nAChR agonists is proportional to total radiolabeled transmitter released (37). Baseline release was determined as the average of 2 fractions before and 2 fractions after the peak release. Average baseline was subtracted from the evoked release, and the resulting values were divided by the baseline to yield the evoked release as a percentage over baseline. For all data, except release in α6−/− mice, percentage release over baseline was normalized to average release with nicotine alone. IC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All statistical analyses were performed with Prism. Unless otherwise stated, toxin effects were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's post hoc test for comparisons with nicotine control, using average release with nicotine alone as control.

RESULTS

Hydroxylation of proline6 (Pro6) selectively decreases activity for α6/α3β2β3 vs. α6/α3β4 nAChR

α-CTx BuIA blocks multiple subtypes of nAChRs with nanomolar potency (33). However, α-CTx BuIA distinguishes between β2- vs. β4-containing nAChRs on the basis of off-rate kinetics (33, 38). Thus, α-CTx BuIA reversibly blocks β2-containing nAChRs but blocks β4-containing nAChRs with slow reversibility, suggesting the possibility that this toxin might be engineered to create β4-selective ligands. We initially replaced non-Cys residues in α-CTx BuIA and assessed the potency of these analogs on α6 receptors that contained either a β2 or β4 subunit. Because the α6 subunit does not form functional receptors, we used a surrogate formed by splicing the N-terminal extracellular ligand-binding region of the α6 subunit with the remaining fragment of the α3 subunit (24). The pharmacology of this chimera has previously been shown to match that of native α6* nAChRs (28, 39, 40). Dose-response curves for inhibition of heterologously expressed rat α6/α3β2β3 and α6/α3β4 nAChRs by α-CTx BuIA analogs (Fig. 1) are shown in Fig. 2 and corresponding IC50 values are shown in Table 1.

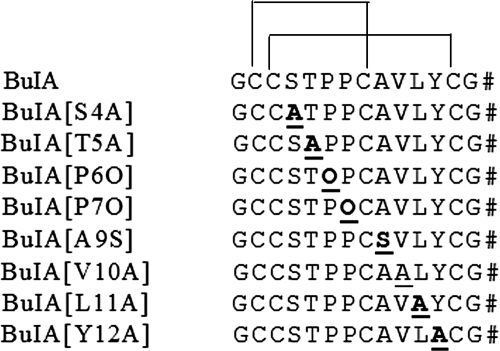

Figure 1.

Sequences of native α-CTx BuIA and analogs. For each analog, the amino acid that is substituted is bold and underscored. Disulfide bond connectivity is also shown. Pound sign (#) indicates an amidated C terminus.

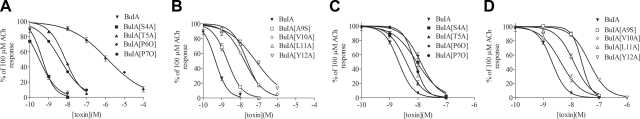

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves for blocking of nAChR subtypes α6/α3β2β3 (A, B) and α6/α3β4 (C, D) by α-CTx BuIA analogs. Data are means ± se from ≥3 separate oocytes. IC50 and Hill slope values are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

IC50 values for the BuIA analogs on rat α6/α3β2β3 and α6/α3β4 nAChRs

| Toxin | α6/α3β2β3 |

α6/α3β4 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Hill coefficient | IC50 | Hill coefficient | |

| BuIA | 0.46 (0.31–0.0.61) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| BuIA[S4A] | 0.32 (0.27–0.38) | 0.9 ± 0.05 | 9.1 (5.2–16) | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| BuIA[T5A] | 7.6 (6.8–8.4) | 1.0 ± 0.04 | 3.8 (3.2–4.7) | 1.4 ± 0.10 |

| BuIA[P6O] | 1300 (880–1900) | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 12 (9.8–16) | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| BuIA[P7O] | 4.1 (3.6–4.6) | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 7.7 (4.2–14) | 2.1 ± 1.7 |

| BuIA[A9S] | 2.0 (1.7–2.5) | 1.1 ± 0.08 | 24 (17–33) | 2.5 ± 0.4 |

| BuIA[V10A] | 17 (15–19) | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 4.3 (2.9–6.3) | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| BuIA[L11A] | 23 (19–29) | 1.1 ± 0.09 | 12 (10–15) | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| BuIA[Y12A] | 69 (49–95) | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 44 (38–52) | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

Residue replacement at each position tested affects the potency of the toxin for both nAChR subtypes, but the biggest loss in potency for the α6/α3β2β3 subtype occurs when Pro6 is replaced by 4-Hyp; the smallest loss of activity for the α6/α3β4 subtype is with α-CTx BuIA[T5A] (underscored). IC50 values are nanomolar (95% CI). Hill coefficients are means ± se from 3–5 separate oocytes.

All analogs lost potency in blocking α6/α3β2β3 relative to native toxin. The loss in potency was by far the greatest when Pro6 was replaced by 4-hydroxyproline (4-Hyp, O): α-CTx BuIA[P6O] relative to wild-type α-CTx BuIA was ∼2800-fold less potent in blocking α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs. In contrast, α-CTx BuIA[P6O] was only 6-fold less potent than native toxin in blocking α6/α3β4 nAChRs (Table 1). Likewise, other analogs of α-CTx BuIA also selectively lost potency at α6/α3β2β3 compared with α6/α3β4 nAChRs, but the relative magnitudes of the differences were more modest. Two of these analogs, α-CTx BuIA[P6O] and α-CTx BuIA[Y12A], displayed Hill coefficients < 1 on α6/α3β2β3 nAChR (Table 1). This result could be due to these toxins binding to different stoichiometries of the receptor, such as those shown to exist for α4β2 nAChRs (41). This possibility was not further investigated.

α-CTx BuIA [T5A;P6O] further discriminates between α6/α3β4 and α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs

Although α-CTx BuIA[P6O] can discriminate between α6/α3β4 and α6/α3β2β3, the selectivity window is only ∼100-fold. Therefore, an attempt was made to generate an analog with further refined specificity. Two notable α-CTx BuIA analogs are α-CTx BuIA[T5A] and α-CTx BuIA[P6O], the former for showing the least loss in potency on α6/α3β4 nAChR and the latter for the most loss in potency on α6/α3β2β3 nAChR (Table 1). Therefore, both mutations were combined to generate the analog α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O]. The double-mutant analog was able to discriminate between α6/α3β4 and α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs better than the single mutant analog α-CTx BuIA[P6O] (Fig. 3; Table 2). α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocked rat α6/α3β4 nAChR with an IC50 of 58.1 nM, whereas even at 10 μM, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] did not show appreciable block of α6/α3β2β3 (Table 2; Fig. 3). Similarly, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] potently blocked heterologously expressed mouse α6/α3β4, whereas it did not show any block of α6/α3β2β3 at concentrations up to 10 μM (Table 2; Fig. 3). In both species, α-CTxBuIA[T5A;P6O] also blocked α3β4 nAChRs, although less potently than α6/α3β4 (Table 2; Fig. 3). Differences among Hill slopes between species were not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Concentration-response curves for blocking of nAChR subtypes by α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O]. A) α-CTx BuIA blocks rat α6/α3β4 with nanomolar potency, whereas it displays micromolar potency in blocking α3β4 and has little to no effect on the other nAChR subtypes. B) α-CTx BuIA blocks the mouse α6/α3β4 subtype with nanomolar potency, whereas it displays micromolar potency in blocking α3β4 and little effect on the other subtypes. Data are means ± se from ≥3 separate oocytes. IC50 and Hill slope values are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

IC50 values for α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] on rat and mouse nAChR subtypes

| nAChR subtype | Rat |

Mouse |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Hill coefficient | IC50 | Hill coefficient | |

| α2β2 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ||

| α2β4 | ≈5,000 | >10,000 | ||

| α3β2 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ||

| α3β4 | 1200 (969–1390) | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 664 (450–979) | 1.8 ± 0.6 |

| α4β2 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ||

| α4β4 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ||

| α6/α3β2β3 | >10,000 | >10,000 | ||

| α6/α3β4 | 58.1 (50.2–67.3) | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 94.3 (78.3–114) | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| α7 | >10,000 | ND | ||

| α9α10 | >10,000 | ND | ||

| Muscle | N.D. | >10,000 | ||

α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocks only the α6/α3β4 nAChR with high potency. α3β4 nAChRs are also blocked, although with lower potency. IC50 values are nanomolar (95% CI). Hill coefficients are means ± se from 3–5 separate oocytes. ND, not determined.

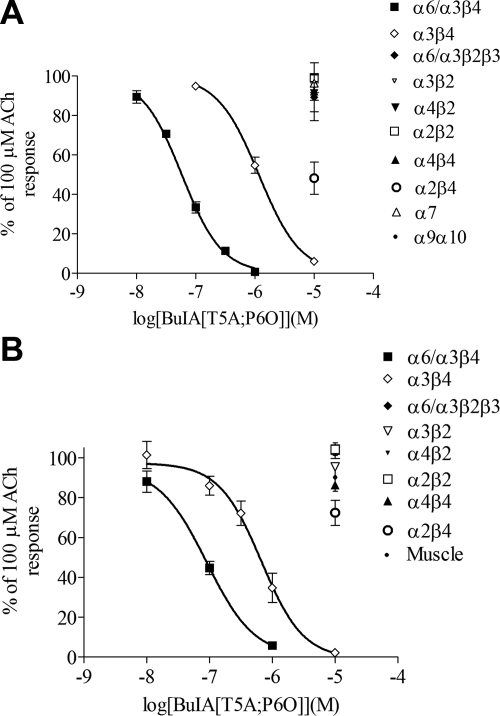

Wild-type α-CTx BuIA potently blocked both α6/α3β2β3 and α6/α3β4 nAChRs yet displayed distinct binding kinetics for the two subtypes. On toxin washout, block of α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs by wild-type α-CTx BuIA was rapidly reversed, whereas block of α6/α3β4 nAChRs was only slowly reversed (Fig. 4A). In contrast, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] potently blocked α6/α3β4 but not α6α3β2β3 nAChRs (Table 2; Fig. 4B). In addition, compared with wild-type BuIA, the off-rate of α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] on α6/α3β4 nAChR was much faster (Fig. 4C). Block of α6/α3β4 nAChR by 1 μM α-CTx BuIA [T5A;P6O] was fully reversed in<10 min on toxin washout.

Figure 4.

Differential binding and kinetics of α-CTx BuIA and α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] on α6/α3β2β3 andα6/α3β4 nAChRs. Representative responses in a single oocyte expressing each nAChR subtype are shown. A) Wild-type α-CTx BuIA blocks both α6/α3β4 and α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs. Block is pseudoirreversible on α6/α3β4 nAChRs, whereas block reverses in minutes after washout from α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs. nAChRs were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. After a control response to 100 μM ACh, toxin was perfusion applied at the indicated concentrations. Toxin was then washed out, and responses to ACh were again measured at 1-min intervals. B) α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocks α6/α3β4 but not α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs. Blocking of α6/α3β4 by α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] reverses on a minute time frame. Broken bar indicates perfusion application of toxin; solid bar indicates static bath application for 5 min. C) Individual peak currents for α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocking of each subtype. Lack of effect of 10 μM α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] on α6/α3β2β3 nAChR is shown for comparison.

α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] partially blocks nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release from hippocampus but not DA release from striatum

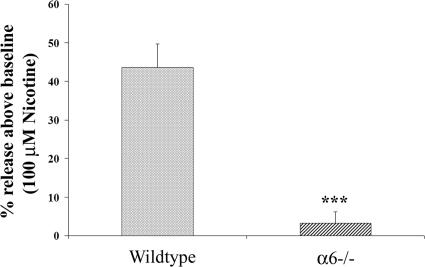

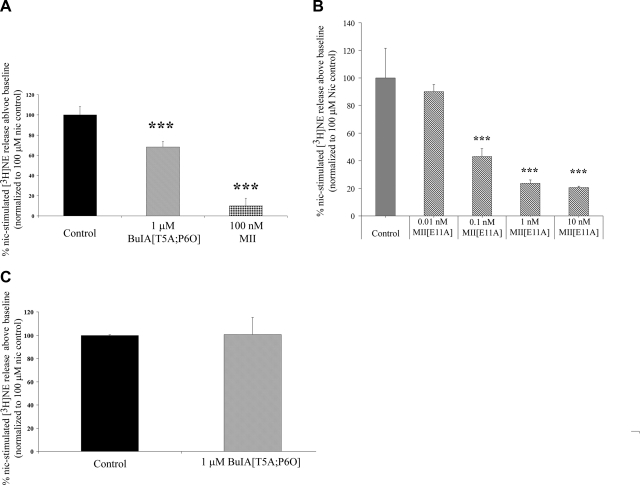

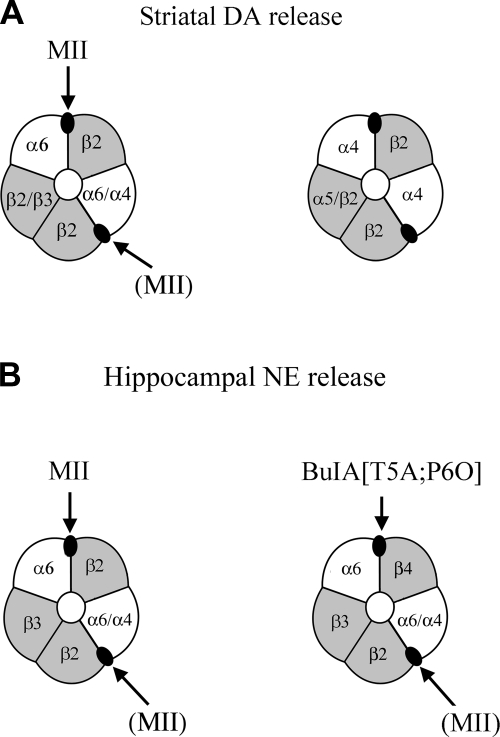

Both non-α6* and, to a lesser extent, α6* nAChRs modulate nicotine-evoked DA release from striatal synaptosomes. The subtype composition of these receptors is α4(α5)β2 and α6(α4)β2β3 as determined by a combination of studies using receptor binding, immunoprecipitation, and subunit-knockout mice (26, 28, 30, 39, 42). In contrast, the molecular composition of nAChRs that mediate hippocampal NE release is less clear. We used α6−/− mice to assess the role of the α6 subunit. Knockout of the α6 subunit abolished nicotine-stimulated NE release (release over baseline: 3.22±2.95%) (Fig. 5). There was no significant difference in total tissue uptake of [3H]NE between α6−/− and wild-type mice (wild-type uptake: 56,727±5676 cpm, α6−/− uptake: 48,211±7017 cpm, P=0.36, Student's t test). Thus, in contrast to DA release, the α6 subunit seems to be requisite for all or nearly all nicotine-stimulated NE release. Consistent with this result, 100 nM α-CTx MII, which blocks both α6β2 (IC50 of 0.39 nM) (24) and α6β4 nAChRs (IC50 of 22 nM) (unpublished results) blocked 90 ± 7.8% of nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release (Fig. 6A).

Figure 5.

Deletion of the α6 subunit abolishes nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release. Data are shown as percentage release over baseline. Values are means ± se from ≥3 separate experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. wild-type release; Student's unpaired t test.

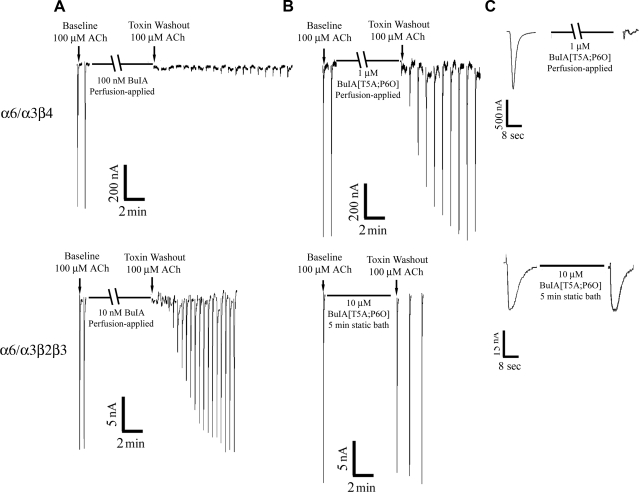

Figure 6.

Effect of α-CTxs on nicotine-stimulated NE release. A) α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocks nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release from mouse hippocampal synaptosomes by 32 ± 5.3%. Release is blocked by 90 ± 7.8% by α-CTx MII. ***P < 0.001, F(2,51) = 79.35, Dunnett's post hoc test. B) α-CTx MII[E11A] potently blocks nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release. ***P < 0.001; F(4,9) = 20.77; Dunnett's post hoc test. C) α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] does not block nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release in hippocampal synatosomes from β4−/− mice.

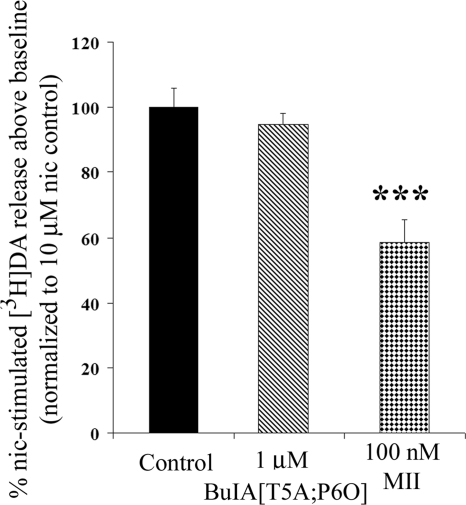

We next used α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] and α-CTx MII[E11A] to further assess the contribution of α6β4* and α6β2* nAChRs to nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release. A saturating concentration of α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocked nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release by 32 ± 5.3% (Fig. 6A). Thus, approximately one-third of hippocampal NE release is modulated by an α6β4* nAChR. This result indicates that approximately two-thirds is modulated by nAChRs containing an α6(non-β4)* subtype, most likely α6β2*, as suggested previously (31). This hypothesis was further confirmed as follows. First, if an α6β4 nAChR modulates a portion of release, then α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] should not block nicotine stimulated [3H]NE release in β4-subunit-knockout mice. Consistent with this finding, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] at 1 μM failed to block hippocampal NE release in β4−/− mice (Fig. 6C). Second, if α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] is selective for native α6β4 nAChRs vs. α6β2 nAChRs, then it should fail to block α6β2*-mediated DA release in striatum; indeed, no block was observed (Fig. 7). This striatal DA release was, however, α-CTx MII-sensitive, with 100 nM α-CTx MII blocking 41 ± 6.7% of nicotine-stimulated release (Fig. 7). Thus, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] does not block native α-CTx MII-sensitive α6β2* nAChRs in striatum, consistent with the pharmacology observed in oocyte studies (Table 2; Fig. 3). Third, α-CTx MII[E11A] should block [3H]NE release. Results from α6−/− mice indicated that the α6 subunit is an essential part of the nAChRs that modulate NE release. This finding does not, however, exclude the possibility of an α3 subunit at a ligand-binding interface. We therefore assessed the effect of α-CTx MII[E11A], which selectively blocks α6* over α3* nAChRs (24). Dose-dependent block of NE release was observed with α-CTx MII[E11A] (Fig. 6B). α-CTx MII[E11A] blocked nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release with an IC50 similar to block of α6β2* nAChRs in oocytes (IC50 for blocking NE release: 0.114 nM, 95% CI 0.047–0.274 nM; IC50 for block of α6β2* nAChR: 0.160 nM; ref. 24), consistent with α6* nAChRs being predominantly responsible for modulating [3H]NE release. This result is also consistent with block of NE release by the α6-preferring α-CTx PIA (31). Taken together, these results indicate that hippocampal NE release in mice, but not striatal DA release, is partially mediated by an α6β4* nAChR. In addition, α6β2* nAChRs mediate both NE release in hippocampus and (as previously shown in other studies) DA release in striatum. The results also confirm the ability of α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] to discriminate between native α6β4* and α6β2* nAChRs.

Figure 7.

Effect of α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] on nicotine-stimulated DA release. α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] does not inhibit nicotine-stimulated [3H]DA release from mouse striatal synaptosomes at concentrations as high as 1 μM. α-CTx MII blocks 41 ± 6.7% of [3H]DA release. Data are means ± se from ≥3 separate experiments. ***P < 0.001; F(4,35) = 6.85; Dunnett's post hoc test analysis.

DISCUSSION

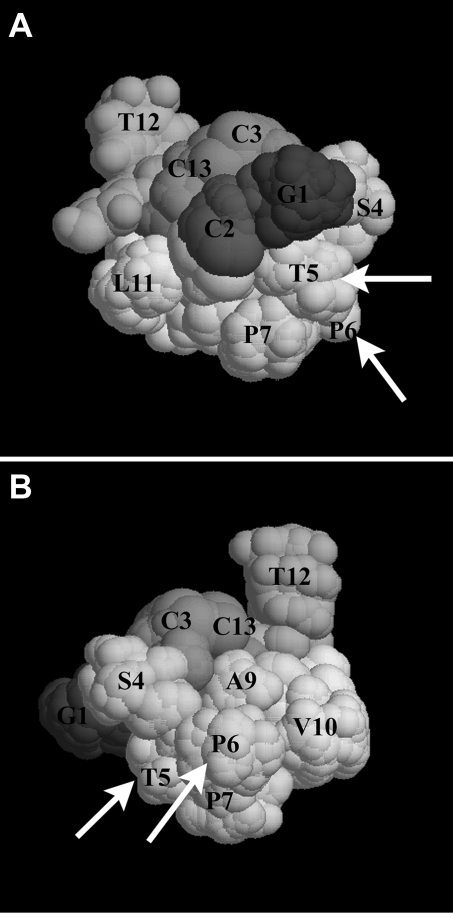

In this study, we report the synthesis and characterization of α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a ligand able to selectively block α6β4* vs. α6β2* nAChRs. The wild-type α-CTx BuIA is 4.5-fold more potent on α6/α3β2β3 than on α6/α3β4 nAChRS. In contrast, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] has the reverse selectivity: it is >200-fold more potent on α6/α3β4 than on α6/α3β2β3 (we did not test a higher concentration than 10 μM toxin to determine an IC50 for α6/α3β2β3). The selectivity of this new ligand is largely dependent on the change of Pro6 to 4-Hyp. Pro6 is a highly conserved residue among α-CTxs (Table 3). The change of this conserved Pro to 4-Hyp in other α-conotoxins has been associated with loss of activity. Modification of α-CTx PnIB resulted in a 19-fold loss, and modification of α-CTx ImI resulted in a >33-fold loss of activity at homomeric α7 nAChRs (43, 44). A surprising result of the present study is the very large loss in activity on α6/α3β2β3 compared with that seen for α6/α3β4 nAChRs. Mutation of α-CTx BuIA Pro6 to 4-Hyp shifted the IC50 for α6/α3β2β3 nAChRs from 0.46 to 1300 nM, a change of 3 orders of magnitude. In contrast, the same mutation increased the IC50 for α6/α3β4 by only 6-fold. Thus, hydroxylation of Pro has widely varying effects on different subtypes of nAChRs but in the present case enabled the creation of a selective ligand. Figure 8 shows the solution structure of α-CTx BuIA (45), with arrows showing the location of the 2 mutated residues, Thr5 and Pro6.

Table 3.

Sequences of α-conotoxins highlighting the conserved Pro6, which in α-CTx BuIA plays an important role in interacting with α6/α3β2β3 nAChR

| Toxin | Sequence |

|---|---|

| α-CTx BuIA | GCCSTPPCAVLYC# |

| α-CTx ImI | GCCSDPRCAWRC# |

| α-CTx MII | GCCSNPVCHLEHSNLC# |

| α-CTx PIA | RDPCCSNPVCTVHNPQIC# |

| α-CTx OmIA | GCCSHPACNVNNPHICG# |

| α-CTx AuIB | GCCSYPPCFATNPDC# |

| α-CTx PeIA | GCCSHPACSVNHPELC# |

| α-CTx Vc1.1 | GCCSDPRCNYDHPEIC# |

| α-CTx RgIA | GCCSDPRCRYRCR^ |

| α-CTx ArIB | DECCSNPACRVNNPHVCRRR^ |

The conserved Pro6 is underscored.

, amidated C terminus;

, free carboxyl.

Figure 8.

Structure of α-CTx BuIA, as determined by NMR (45). Arrows indicate residues that are important for discrimination between α6/α3β2β3 and α6/α3β4 (Thr5 and Pro6). Two views; panel B shows 180° rotation along the axis of view in panel A.

Hyp is a naturally occurring post-translational modification of Pro, well characterized in collagen-like polypeptides (46). Pro-Hyp-Gly repeats stabilize the collagen triple helix. Hydroxylation of Pro requires ascorbic acid, and vitamin C deficiency results in decreased stability of collagen-containing tissue. Clinically, this deficiency manifests itself as bleeding from mucus membranes and spongy gums, a condition known as scurvy (47, 48). 4-Hyp has also been found in Conus venom peptides (49). Although the role of 4-Hyp in Conus is not known, the present report raises the possibility that hydroxylation might be used by Conus as a method of sharpening conotoxin selectivity.

A number of previously discovered α-CTxs have selectivity for α6-containing nAChRs. α-CTx MII (32) is widely used to study α6β2β3 and α3β2 nAChRs, and subsequent analogs, including α-CTx MII[E11A], α-CTx MII[H9A;L15A], and α-CTx MII[S4A;E11A;L15A], have refined selectivity (24, 50). Use of α-CTx MII and its analogs has facilitated mechanistic understanding of the role of α6β2β3 nAChRs in DA release (30, 42, 51). Dopamine release is critical to drug abuse, and blocking of α6* nAChRs by α-CTx MII and its analogs has demonstrated a role for α6-containing nAChRs in animal models of nicotine and alcohol addiction (9, 10, 52, 53). Radiolabeled α-CTx MII has been used to demonstrate selective down-regulation of α6* nAChRs in animal models of Parkinson's disease and in human Parkinson's disease (16, 17).

The role of α6β4 nAChRs is less well understood, due in part to lack of specific ligands for this nAChR subtype. α6 nAChRs containing the β4 subunit have been identified by immunoprecipitation in chick and rat retina (54, 55). Other studies have detected transcripts for both subunits in medial/lateral habenula, interpeduncular nucleus, and locus ceruleus (6, 56). Locus ceruleus, which provides noradrenergic projections to the hippocampus, expresses a number of nAChR subunits, including α3–α7 and β2–β4 (6, 57–59). In the present study, we used α6 nAChR-subunit-knockout mice to show that nearly all nicotine-stimulated NE release is mediated by α6-containing nAChRs. No significant release of NE could be detected after nicotine exposure in α6−/− mice (Fig. 5). α-CTx MII, which blocks both α6β2* and α6β4* nAChRs, also effectively blocked NE release, confirming a role for α6 nAChRs in wild-type mice. We then used the selectivity of the new ligand α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] to gain further insight as to the molecular forms of α6-containing nAChRs that mediate NE release. A saturating concentration of α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] blocked 32% of nicotine-stimulated [3H]NE release in wild-type mice, indicating that approximately one-third of this release is due to nAChRs containing an α6/β4 interface. α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] failed to block [3H]NE release in β4−/− mice, confirming that α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] does not block α6-containing nAChRs that lack a β4 subunit. Consistent with this finding, α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] also failed to block nicotine-stimulated [3H]DA release in striatum [shown in other studies to be mediated by the α6(α4)β2β3 subtype and α4(α5)β2 subtypes] (for review, see ref. 25). It has previously been shown that α4, β2, and β3 nAChR subunits are essential for nicotine-stimulated NE release in mice (31, 60). The present findings together with the previous results are consistent with the existence of ≥2 populations of nAChRs that underlie nicotine-stimulated NE release in postnatal mice. The subunit composition of these nAChRs is α6α4β2β3 and α6α4β2β3β4 (Fig. 9). The former nAChR subtype is also known to mediate nicotine-stimulated DA release in striatum (25, 30). The latter subtype that contains a β4 subunit mediates NE, but not DA, release and is sensitive to α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] (Figs. 6, 7, and 9). A recent immunoprecipitation study also confirms the absence of the β4 subunit in striatal α6* nAChRs (40).

Figure 9.

Different nAChR subtypes modulate nicotine-stimulated DA vs. NE release. A) Principal nAChR subtypes that mediate DA release in mouse striatum. These receptors lack a β4 subunit, and only a subpopulation contains the α6 subunit (25). B) Principal AChR subtypes that mediate NE release in mouse hippocampus (31). Each subtype contains the α6 subunit. Only a subpopulation contains an α6/β4 subunit interface that is sensitive to blocking by α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O]. Arrow indicates the highest-affinity target of α-CTx. Arrow with label in parentheses indicates the lower-affinity site for α-CTx MII. Note that the majority of subtypes are sensitive to α-CTx MII, whereas only α6β4* nAChR is sensitive to α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O].

These results in mice also further substantiate a major species difference in nAChR subtypes that modulate hippocampal noradrenergic neurotransmission in rats vs. mice. In rats, NE release in hippocampus is mediated by α3β4* and αxβ4 nAChRs (where x is not α6) (31, 61, 62). In contrast, in mice α6* nAChRs modulate all or nearly all NE release (31, this work).

The effect of nicotine on noradrenergic neurotransmission and release in hippocampus may contribute to its mnemonic properties (63, 64). The loss of the noradrenergic projections from the locus ceruleus may, in part, contribute to the cognitive dysfunction observed in Alzheimer's disease (65). The presence of an nAChR subtype (α6α4β2β3β4) that modulates NE, but not DA, release raises the possibility of developing memory-enhancing compounds that lack potentially addicting properties via activation of α6α4β2β3β4 nAChRs.

In summary, α-CTx BuIA, a peptide that blocks multiple nAChR subtypes, has been mutated to form a ligand that can discriminate between α6 nAChR subtypes that contain either a β2 or β4 subunit. α-CTx BuIA[T5A;P6O] can be used in combination with receptor-subunit-knockout mice to dissect the molecular composition of native nAChRs, such as those that modulate neurotransmitter release.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Kirschstein-National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship DA 016835 (to L.A.), National Institutes of Health grants DA017173 (to M.D.B.) and MH53631 and GM48677 (to J.M.M.), and Institut Pasteur, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Agence Nationale de la Recherche Neurologie 2005, European Commission European Research and Technological Development NeuroCypres, and ANR Blanc 2008 (to U.M. and J.P.C.). The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework program under grant agreement HEALTH-F2–2008-202088 (NeuroCypres project).

REFERENCES

- 1. Gotti C., Clementi F., Fornari A., Gaimarri A., Guiducci S., Manfredi I., Moretti M., Pedrazzi P., Pucci L., Zoli M. (2009) Structural and functional diversity of native brain neuronal nicotinic receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 78, 703–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gotti C., Moretti M., Gaimarri A., Zanardi A., Clementi F., Zoli M. (2007) Heterogeneity and complexity of native brain nicotinic receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 1102–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Millar N. S., Gotti C. (2009) Diversity of vertebrate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 56, 237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McGehee D. S., Role L. W. (1995) Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57, 521–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gotti C., Zoli M., Clementi F. (2006) Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 482–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Le Novere N., Zoli M., Changeux J. P. (1996) Neuronal nicotinic receptor α6 subunit mRNA is selectively concentrated in catecholaminergic nuclei of the rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 8, 2428–2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Azam L., Winzer-Serhan U., Leslie F. M. (2003) Co-expression of α7 and β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNAs within rat brain cholinergic neurons. Neuroscience 119, 965–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Azam L., Winzer-Serhan U. H., Chen Y., Leslie F. M. (2002) Expression of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNAs within midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 444, 260–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pons S., Fattore L., Cossu G., Tolu S., Porcu E., McIntosh J. M., Changeux J. P., Maskos U., Fratta W. (2008) Crucial role of α4 and α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J. Neurosci. 28, 12318–12327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jackson K. J., McIntosh J. M., Brunzell D. H., Sanjakdar S. S., Damaj M. I. (2009) The role of α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in nicotine reward and withdrawal. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331, 547–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perry D. C., Mao D., Gold A. B., McIntosh J. M., Pezzullo J. C., Kellar K. J. (2007) Chronic nicotine differentially regulates α6- and β3-containing nicotinic cholinergic receptors in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322, 306–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perez X. A., Bordia T., McIntosh J. M., Grady S. R., Quik M. (2008) Long-term nicotine treatment differentially regulates striatal α6α4β2* and α6(nonα4) β2* nAChR expression and function. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 844–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walsh H., Govind A. P., Mastro R., Hoda J. C., Bertrand D., Vallejo Y., Green W. N. (2008) Up-regulation of nicotinic receptors by nicotine varies with receptor subtype. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6022–6032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bohr I. J., Ray M. A., McIntosh J. M., Chalon S., Guilloteau D., McKeith I. G., Perry R. H., Clementi F., Perry E. K., Court J. A., Piggott M. A. (2005) Cholinergic nicotinic receptor involvement in movement disorders associated with Lewy body diseases. An autoradiography study using [125)I] α-conotoxin MII in the striatum and thalamus. Exp. Neurol. 191, 292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gotti C., Moretti M., Bohr I., Ziabreva I., Vailati S., Longhi R., Riganti L., Gaimarri A., McKeith I. G., Perry R. H., Aarsland D., Larsen J. P., Sher E., Beattie R., Clementi F., Court J. A. (2006) Selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit deficits identified in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies by immunoprecipitation. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quik M., McIntosh J. M. (2006) Striatal α6* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: potential targets for Parkinson's disease therapy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 316, 481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bordia T., Grady S. R., McIntosh J. M., Quik M. (2007) Nigrostriatal damage preferentially decreases a subpopulation of α6β2* nAChRs in mouse, monkey, and Parkinson's disease striatum. Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moretti M., Vailati S., Zoli M., Lippi G., Riganti L., Longhi R., Viegi A., Clementi F., Gotti C. (2004) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes expression during rat retina development and their regulation by visual experience. Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Azam L., McIntosh J. M. (2009) α-Conotoxins as pharmacological probes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30, 771–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicke A., Wonnacott S., Lewis R. J. (2004) α-Conotoxins as tools for the elucidation of structure and function of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2305–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ellison M., Haberlandt C., Gomez-Casati M. E., Watkins M., Elgoyhen A. B., McIntosh J. M., Olivera B. M. (2006) α-RgIA: a novel conotoxin that specifically and potently blocks the α9α10 nAChR. Biochemistry 45, 1511–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Innocent N., Livingstone P. D., Hone A., Kimura A., Young T., Whiteaker P., McIntosh J. M., Wonnacott S. (2008) α-Conotoxin Arenatus IB[V11L,V16D] [corrected] is a potent and selective antagonist at rat and human native α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 327, 529–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whiteaker P., Christensen S., Yoshikami D., Dowell C., Watkins M., Gulyas J., Rivier J., Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M. (2007) Discovery, synthesis, and structure activity of a highly selective α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. Biochemistry 46, 6628–6638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McIntosh J. M., Azam L., Staheli S., Dowell C., Lindstrom J. M., Kuryatov A., Garrett J. E., Marks M. J., Whiteaker P. (2004) Analogs of α-conotoxin MII are selective for α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 944–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grady S. R., Salminen O., Laverty D. C., Whiteaker P., McIntosh J. M., Collins A. C., Marks M. J. (2007) The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 1235–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grady S. R., Salminen O., McIntosh J. M., Marks M. J., Collins A. C. (2010) Mouse striatal dopamine nerve terminals express α4α5β2 and two stoichiometric forms of α4β2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Mol. Neurosci. 40, 91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grady S. R., Murphy K. L., Cao J., Marks M. J., McIntosh J. M., Collins A. C. (2002) Characterization of nicotinic agonist-induced [3H]dopamine release from synaptosomes prepared from four mouse brain regions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 301, 651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Champtiaux N., Gotti C., Cordero-Erausquin M., David D. J., Przybylski C., Lena C., Clementi F., Moretti M., Rossi F. M., Le Novere N., McIntosh J. M., Gardier A. M., Changeux J. P. (2003) Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 23, 7820–7829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cui C., Booker T. K., Allen R. S., Grady S. R., Whiteaker P., Marks M. J., Salminen O., Tritto T., Butt C. M., Allen W. R., Stitzel J. A., McIntosh J. M., Boulter J., Collins A. C., Heinemann S. F. (2003) The β3 nicotinic receptor subunit: a component of α-conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate dopamine release and related behaviors. J. Neurosci. 23, 11045–11053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salminen O., Murphy K. L., McIntosh J. M., Drago J., Marks M. J., Collins A. C., Grady S. R. (2004) Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 1526–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Azam L., McIntosh J. M. (2006) Characterization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate nicotine-evoked [3H]norepinephrine release from mouse hippocampal synaptosomes. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 967–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cartier G. E., Yoshikami D., Gray W. R., Luo S., Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M. (1996) A new α-conotoxin which targets α3β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7522–7528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Azam L., Dowell C., Watkins M., Stitzel J. A., Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M. (2005) α-Conotoxin BuIA, a novel peptide from Conus bullatus, distinguishes among neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Champtiaux N., Han Z. Y., Bessis A., Rossi F. M., Zoli M., Marubio L., McIntosh J. M., Changeux J. P. (2002) Distribution and pharmacology of α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J. Neurosci. 22, 1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu W., Orr-Urtreger A., Nigro F., Gelber S., Sutcliffe C. B., Armstrong D., Patrick J. W., Role L. W., Beaudet A. L., De Biasi M. (1999) Multiorgan autonomic dysfunction in mice lacking the β2 and the β4 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 19, 9298–9305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kulak J. M., Nguyen T. A., Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M. (1997) α-Conotoxin MII blocks nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in rat striatal synaptosomes. J. Neurosci. 17, 5263–5270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rapier C., Lunt G. G., Wonnacott S. (1988) Stereoselective nicotine-induced release of dopamine from striatal synaptosomes: concentration dependence and repetitive stimulation. J. Neurochem. 50, 1123–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shiembob D. L., Roberts R. L., Luetje C. W., McIntosh J. M. (2006) Determinants of α-conotoxin BuIA selectivity on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor β subunit. Biochemistry 45, 11200–11207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zoli M., Moretti M., Zanardi A., McIntosh J. M., Clementi F., Gotti C. (2002) Identification of the nicotinic receptor subtypes expressed on dopaminergic terminals in the rat striatum. J. Neurosci. 22, 8785–8789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gotti C., Guiducci S., Tedesco V., Corbioli S., Zanetti L., Moretti M., Zanardi A., Rimondini R., Mugnaini M., Clementi F., Chiamulera C., Zoli M. (2010) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mesolimbic pathway: primary role of ventral tegmental area α6β2* receptors in mediating systemic nicotine effects on dopamine release, locomotion, and reinforcement. J. Neurosci. 30, 5311–5325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moroni M., Bermudez I. (2006) Stoichiometry and pharmacology of two human α4β2 nicotinic receptor types. J. Mol. Neurosci. 30, 95–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Salminen O., Drapeau J. A., McIntosh J. M., Collins A. C., Marks M. J., Grady S. R. (2007) Pharmacology of α-conotoxin MII-sensitive subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors isolated by breeding of null mutant mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 1563–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lopez-Vera E., Walewska A., Skalicky J. J., Olivera B. M., Bulaj G. (2008) Role of hydroxyprolines in the in vitro oxidative folding and biological activity of conotoxins. Biochemistry 47, 1741–1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Quiram P. A., McIntosh J. M., Sine S. M. (2000) Pairwise interactions between neuronal α7 acetylcholine receptors and α-conotoxin PnIB. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4889–4896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chi S. W., Kim D. H., Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M., Han K. H. (2006) NMR structure determination of α-conotoxin BuIA, a novel neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist with an unusual 4/4 disulfide scaffold. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 349, 1228–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Berisio R., Granata V., Vitagliano L., Zagari A. (2004) Imino acids and collagen triple helix stability: characterization of collagen-like polypeptides containing Hyp-Hyp-Gly sequence repeats. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11402–11403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pimentel L. (2003) Scurvy: historical review and current diagnostic approach. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 21, 328–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Peterkofsky B. (1991) Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54, 1135S–1140S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Terlau H., Olivera B. M. (2004) Conus venoms: a rich source of novel ion channel-targeted peptides. Physiol. Rev. 84, 41–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Azam L., Yoshikami D., McIntosh J. M. (2008) Amino acid residues that confer high selectivity of the α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit to α-conotoxin MII[S4A,E11A,L15A]. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11625–11632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Azam L., McIntosh J. M. (2005) Effect of novel α-conotoxins on nicotine-stimulated [3H]dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 312, 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lof E., Olausson P., deBejczy A., Stomberg R., McIntosh J. M., Taylor J. R., Soderpalm B. (2007) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the ventral tegmental area mediate the dopamine activating and reinforcing properties of ethanol cues. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 195, 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brunzell D. H., Boschen K. E., Hendrick E. S., Beardsley P. M., McIntosh J. M. (2010) α-Conotoxin MII-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell regulate progressive ratio responding maintained by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 665–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vailati S., Hanke W., Bejan A., Barabino B., Longhi R., Balestra B., Moretti M., Clementi F., Gotti C. (1999) Functional α6-containing nicotinic receptors are present in chick retina. Mol. Pharmacol. 56, 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Marritt A. M., Cox B. C., Yasuda R. P., McIntosh J. M., Xiao Y., Wolfe B. B., Kellar K. J. (2005) Nicotinic cholinergic receptors in the rat retina: simple and mixed heteromeric subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 1656–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Quik M., Polonskaya Y., Gillespie A., Jakowec M., Lloyd G. K., Langston J. W. (2000) Localization of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey brain by in situ hybridization. J. Comp. Neurol. 425, 58–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lena C., de Kerchove D'Exaerde A., Cordero-Erausquin M., Le Novere N., del Mar Arroyo-Jimenez M., Changeux J. P. (1999) Diversity and distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the locus ceruleus neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 12126–12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Goldner F. M., Dineley K. T., Patrick J. W. (1997) Immunohistochemical localization of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit α6 to dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. Neuroreport 8, 2739–2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vincler M. A., Eisenach J. C. (2003) Immunocytochemical localization of the α3, α4, α5, α7, β2, β3 and β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Brain Res. 974, 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Scholze P., Orr-Urtreger A., Changeux J. P., McIntosh J. M., Huck S. (2007) Catecholamine overflow from mouse and rat brain slice preparations evoked by nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation and electrical field stimulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151, 414–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Clarke P. B., Reuben M. (1996) Release of [3H]-noradrenaline from rat hippocampal synaptosomes by nicotine: mediation by different nicotinic receptor subtypes from striatal [3H]-dopamine release. Br. J. Pharmacol. 117, 595–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Luo S., Kulak J. M., Cartier G. E., Jacobsen R. B., Yoshikami D., Olivera B. M., McIntosh J. M. (1998) α-Conotoxin AuIB selectively blocks α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotine-evoked norepinephrine release. J. Neurosci. 18, 8571–8579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee E. H., Lee C. P., Wang H. I., Lin W. R. (1993) Hippocampal CRF, NE, and NMDA system interactions in memory processing in the rat. Synapse 14, 144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lee E. H., Ma Y. L. (1995) Amphetamine enhances memory retention and facilitates norepinephrine release from the hippocampus in rats. Brain Res. Bull. 37, 411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weinshenker D. (2008) Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 342–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]