Abstract

AIM: To investigate the clinicopathologic features of bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) occurrence after treatment of primary small hepatocellular carcinoma (sHCC).

METHODS: A total of 423 patients with primary sHCC admitted to our hospital underwent surgical resection or local ablation. During follow-up, only six patients were hospitalized due to obstructive jaundice, which occurred 5-76 mo after initial treatment. The clinicopathologic features of these six patients were reviewed.

RESULTS: Six patients underwent hepatic resection (n = 5) or radio-frequency ablation (n = 1) due to primary sHCC. Five cases had an R1 resection margin, and one case had an ablative margin less than 5.0 mm. No vascular infiltration, microsatellites or bile duct/canaliculus affection was noted in the initial resected specimens. During the follow-up, imaging studies revealed a macroscopic BDTT extending to the common bile duct in all six patients. Four patients had a concomitant intrahepatic recurrent tumor. Surgical re-resection of intrahepatic recurrent tumors and removal of BDTTs (n = 4), BDTT removal through choledochotomy (n = 1), and conservative treatment (n = 1) was performed. Microscopic portal vein invasion was noted in three of the four resected specimens. All six patients died, with a mean survival of 11 mo after BDTT removal or conservative treatment.

CONCLUSION: BDTT occurrence is a rare, special recurrent pattern of primary sHCC. Patients with BDTTs extending to the common bile duct usually have an unfavorable prognosis even following aggressive surgery. Insufficient resection or ablative margins against primary sHCC may be a risk factor for BDTT development.

Keywords: Small hepatocellular carcinoma, Recurrence, Bile ducts, Jaundice, Diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies, especially in Asian countries[1]. With advanced imaging techniques, small HCC (sHCC) (≤ 3.0 cm) can be detected with increasing ease during screening in patients with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis. Surgical resection and local ablation therapy (including percutaneous ethanol injection, percutaneous microwave coagulation, and percutaneous radio-frequency ablation) are effective against sHCC[2-4]. Although major progress has been made in the detection and treatment of sHCC, the efficacy of sHCC treatments remains undesirable: the 3- and 5-year disease-free survival rates are only 49% and 30%, respectively[5]. A major cause of the unfavorable prognosis of sHCC is the high incidence of postoperative recurrence. Kumada et al[6] reported that the cumulative 3- and 5-year recurrence rates were up to 64.5% and 76.1%, respectively. HCC recurrence is a leading cause of death that affects patients’ long-term survival.

Extrahepatic and intrahepatic recurrences are two different sHCC recurrent patterns. Extrahepatic recurrence may extend to lymph nodes, peritoneum and extra-abdominal organs, while intrahepatic recurrence includes local recurrence, intrahepatic metastasis and multicentric carcinogenesis in the remnant liver[6-10]. However, bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) occurrence is rarely reported as a recurrent pattern of primary sHCC. Herein we present the clinicopathologic features of six patients with macroscopic BDTT occurrence after primary sHCC resection or local ablation. To the best of our knowledge, there is no such report in the English-language literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between March 2002 and June 2010, 423 patients with primary sHCC admitted to our hospital underwent surgical resection or local ablation. Patients were followed up every 1 or 3 mo after initial treatment. During follow-up, only six patients were hospitalized due to obstructive jaundice, which occurred at 5-76 mo (median, 8.5 mo) after the initial treatment. We retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathologic features of the six sHCC patients who developed a BDTT after treatment. The surgical margin was classified by an experienced pathologist (HG Li) as follows. R0 resection indicated complete removal of all tumors without microscopic tumor cells in the surgical margin. R1 resection indicated that the edges of the resection specimen showed microscopic tumor cells. R2 resection indicated that portions of tumor visible to the naked eye were not removed.

RESULTS

The sex, age, chief complaint, hepatitis markers, presence of cirrhosis, α-fetoprotein (AFP) level, location and size of sHCC, treatment, and pathological diagnosis at the initial hospital visit are summarized in Table 1 for the six patients with primary sHCC. The patients were all male, with a median age of 44 years. Three patients had epigastric pain, while the others were asymptomatic. Five patients were hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive, and one was HBsAg-negative. The serum AFP level was elevated in each patient, ranging from 25.0 to 725.3 ng/mL (normal, ≤ 10.0 ng/mL). The primary sHCCs were 1.5-2.7 cm in diameter. Five patients underwent hepatic resection, and pathological examination showed poorly differentiated (n = 3) or moderately differentiated HCC (n = 2). One patient (case 3) underwent a biopsy before radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and the tumor was moderately differentiated HCC. Five cases had an R1 resection margin, and one case had an ablative margin less than 5.0 mm. No vascular infiltration, microsatellites or bile duct/canaliculus invasion was noted in the initial resected specimens.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of six cases of small hepatocellular carcinoma at the initial diagnosis

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | |

| Sex/age (yr) | M/35 | M/57 | M/45 | M/50 | M/38 | M/41 |

| Chief complaint | Epigastric pain | Asymptomatic | Asymptomatic | Epigastric pain | Asymptomatic | Epigastric pain |

| HBsAg/HCV-Ab | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | -/- |

| Liver cirrhosis | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 203.5 | 25 | 283 | 226.1 | 578.3 | 725.3 |

| sHCC location/size | VIII/2.7 cm | V/2.0 cm | VI/1.5 cm | IV/2.0 cm | V/1.6 cm | VI/2.6 cm |

| Treatment | Partial segments V and VIII resection | Partial segment V resection | RF | Left lobectomy | Partial segment V resection | Segments VI and VII resection |

| Resection state | R1 | R1 | Ablative margin less than 5 mm | R1 | R1 | R1 |

| Histologic differentiation | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Poor | Poor | Poor |

| Vascular infiltration | - | - | - | - | + | |

| Tumor microsatellites | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Bile duct or canaliculus invasion | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Capsule presence | - | + | + | + | - |

+: Positive; -: Negative. sHCC: Small hepatocellular carcinoma; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV-Ab: Hepatitis C antibody.

The clinicopathologic features of macroscopic BDTT occurrence after therapy are summarized in Table 2. Imaging examination [computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] revealed macroscopic BDTT and concomitant intrahepatic recurrence in all six patients. Total bilirubin (TBil) and direct bilirubin (DBil) increased in all six patients (normal ranges, ≤ 24.0 μmol/L and ≤ 11.0 μmol/L, respectively). Serum AFP was increased in four patients and was normal in two patients. Four patients showed concomitant intrahepatic recurrent HCC lesions and BDTTs, while the other two revealed no intrahepatic recurrence. Surgical re-resection of the intrahepatic recurrent tumor and removal of the BDTT was performed in four patients, and BDTT removal via choledochotomy was performed in one patient. The other patient (case 6) underwent conservative treatment including percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) because of poor liver function. Histologic examination showed the recurrent tumor or BDTT to be poorly (n = 4) or moderately differentiated HCC (n = 1). All patients died with a mean survival of 11 mo after BDTT removal or conservative treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical characteristics of bile duct tumor thrombus occurrence after treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | |

| Interval1 | 6 mo | 47 mo | 76 mo | 5 mo | 8 mo | 9 mo |

| Chief complaint | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice | Jaundice and epigastric pain | Jaundice | Jaundice |

| TBil/DBil (μmol/L) | 47.1/28.8 | 365.0/283.3 | 286.0/206.5 | 35.7/27.3 | 146.0/87.2 | 480.0/360.3 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 1.3 | 223.5 | 6.7 | 251.6 | 148.5 | 546 |

| Recurrent tumor location/size | VIII/2.0 cm | - | VI/3.2 cm | V, VIII/5.2 cm | VI/2.8 cm | - |

| BDTT location | RIHBD-CBD | CHD-CBD | RIHBD-CBD | RHD-CBD | RIHBD-CBD | RIHBD-CBD |

| Treatment | Hepatic resection and BDTT removal | BDTT removal | Hepatic resection and BDTT removal | Hepatic resection and BDTT removal | Hepatic resection and BDTT removal | PTCD and TACE |

| Resection state | R1 | R1 | R1 | R0 | ||

| Histologic differentiation | Moderate | Poor | Poor | Poor | Poor | |

| Vascular infiltration | - | + | + | + | ||

| Microsatellites | - | + | + | - | ||

| Capsule presence | - | - | - | - | ||

| Survival/prognosis | 13 mo/dead | 4 mo/dead | 19 mo/dead | 14 mo/dead | 10 mo/dead | 6 mo/dead |

Interval between BDTT occurrence and initial treatment. AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; TBil: Total bilirubin; DBil: Direct bilirubin; RIHBD: Right intrahepatic bile duct; CHD: Common hepatic duct; CBD: Common bile duct; RHD: Right hepatic duct; +: Positive; -: Negative; BDTT: Bile duct tumor thrombus.

Clinical course of each case is briefly presented below

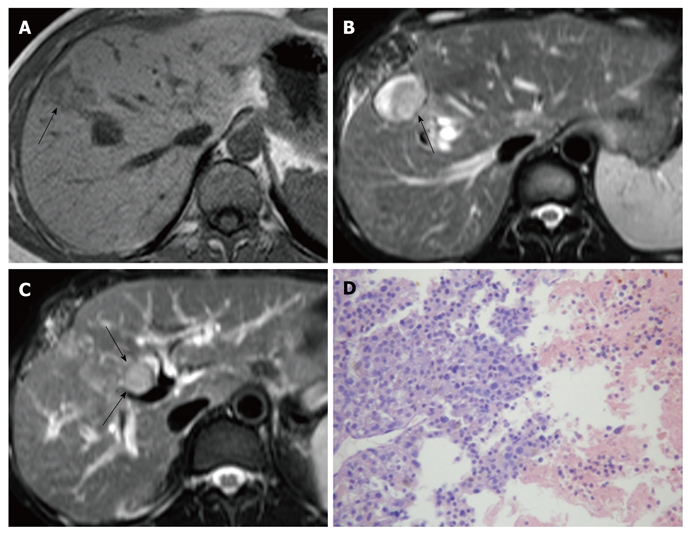

Case 1: A 35-year-old male underwent partial resection of segments V and VIII (Couinaud’s nomenclature) due to a moderately differentiated sHCC measuring 2.7 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). At follow-up 6 mo after the operation, the patient was hospitalized due to jaundice. Serum AFP was normal, and CA19-9 was 350.2 U/mL (normal range, ≤ 35 U/mL). Abdominal sonography and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI examination showed a recurrent tumor of 2.0 cm in diameter at the edge of the residual cavity (segment VIII) after resection of the primary sHCC, and a BDTT extending to the proximal segment of the common bile duct was depicted simultaneously (Figures 1B and C). The BDTT and intrahepatic recurrence were directly connected, and both exhibited typical HCC enhancement characteristics, such as early enhancement in the hepatic arterial phase with rapid wash-out of contrast agent in the portal vein phase on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. The patient underwent partial resection of hepatic segments (IV, VIII) and removal of the BDTT via choledochotomy. Pathological examination showed the intrahepatic recurrent tumor and the BDTT were moderately differentiated HCC (Figure 1D). The patient died 13 mo after surgery due to recurrence.

Figure 1.

Small hepatocellular carcinoma in a 35-year-old male. A: T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows primary sHCC (arrow) in segment VIII; B: T2-weighted MRI shows an intrahepatic recurrent tumor (arrow) at the margin of the residual cavity following resection of primary sHCC; C: A BDTT (arrows) extending through the intrahepatic bile duct into the common bile duct is depicted in a T2-weighted image; D: Histologically, intrahepatic recurrent tumor and BDTT are moderately differentiated HCC [hematoxylin and eosin (HE), × 100]. sHCC: Small hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT: Bile duct tumor thrombus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Case 2: A 57-year-old male underwent partial resection of segment V due to a moderately differentiated sHCC measuring 2.0 cm in diameter (Figure 2A). Forty-three months after the initial operation, the patient underwent resection of segment V again for a recurrent tumor of 1.8 cm in diameter that was detected on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT, and the recurrent tumor was a moderately differentiated HCC with a microscopic BDTT observed pathologically. Four months after the second operation, the patient developed jaundice with increased AFP, and serum CA125 was 122.0 U/mL (normal range, ≤ 35 U/mL). Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT showed no intrahepatic recurrence; however, a BDTT extending through the common hepatic duct to the common bile duct was noted. The BDTT depicted a typical HCC enhancement pattern (Figure 2B). The patient underwent PTCD to relieve jaundice prior to the third operation (Figure 2C). During the third operation, the BDTT was tightly adherent to the common bile duct, so the BDTT was removed through resection of the common bile duct and bilio-enteric reconstruction was performed. The BDTT specimen was positive for hepatocyte on immunohistochemical staining, and cancer nest invasion into the bile duct wall was noted (Figure 2D). The patient died 4 mo after surgery due to hepatic failure.

Figure 2.

Small hepatocellular carcinoma in a 57-year-old male. A: Computed tomography (CT) shows primary sHCC (arrow) in segment V at the hepatic arterial phase; B: Forty-seven months after the initial operation, CT reveals a BDTT (arrows) with characteristics of early enhancement at the hepatic arterial phase; C: Tumor thrombus (arrows) extending through the common hepatic duct into the common bile duct is demonstrated during PTCD; D: Cancer nest invasion into the bile duct wall is observed histologically (HE, × 100). sHCC: Small hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT: Bile duct tumor thrombus; HE: Hematoxylin and eosin; PTCD: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage.

Case 3: A 45-year-old male underwent RFA therapy for a sHCC measuring 1.5 cm in diameter in segment VI. A recurrent tumor of 2.5 cm in diameter was found at the margin of the RFA site 17 mo after the initial RFA. He was again treated with RFA (ablative margin less than 5.0 mm). A recurrent tumor of 2.0 cm in diameter was again found at the margin of the RFA site 18 mo after second RFA therapy. Then TACE was performed. He developed jaundice 41 mo after TACE. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR showed a BDTT extending through the right intrahepatic bile duct to the common bile duct, with typical HCC enhancement characteristics, and a recurrent tumor of 3.2 cm in diameter was found in segment VI. A plastic stent was placed for biliary decompression and drainage. He underwent resection of segment VI and removal of the BDTT via choledochotomy 2 mo after stent placement. Pathological examination showed that the intrahepatic recurrent tumor and the BDTT was poorly differentiated HCC. The patient died 19 mo after surgery due to intrahepatic recurrences and BDTT recurrence.

Case 4: A 50-year-old male underwent left lobectomy due to a poorly differentiated sHCC of 2.0 cm in diameter in segment IV. The patient had epigastric pain and jaundice 5 mo after the operation. Serum AFP was 251.6 ng/mL, and CA19-9 was 399.2 U/mL. MRI revealed a recurrent tumor of 5.2 cm in diameter near the resected hepatic stump (segments V and VIII) and a BDTT extending through the right hepatic duct to the common bile duct. He underwent resection of segments V and VIII and removal of the BDTT through resection of the common bile duct, followed by Roux-en-Y biliary-enteric anastomosis. The intrahepatic recurrence and the BDTT were diagnosed histologically as poorly differentiated HCC, and no bile duct wall invasion was noted. The patient died 14 mo after surgery due to HCC recurrence and distant metastasis.

Case 5: A 38-year-old male underwent partial resection of segment V due to a poorly differentiated sHCC of 1.6 cm in diameter. The patient developed obstructive jaundice 8 mo after the operation. CT showed a recurrent tumor of 2.8 cm in diameter in segment VI and a BDTT extending through the right intrahepatic bile duct to the common bile duct. The patient received re-resection of segment VI and removal of the BDTT via choledochotomy. Histologically, the intrahepatic recurrence and the BDTT were diagnosed as poorly differentiated HCC. The patient died 10 mo after surgery due to distant metastasis.

Case 6: A 41-year-old male underwent resection of segment VI due to a poorly differentiated sHCC of 2.6 cm in diameter (Figure 3A). He developed jaundice 9 mo after the operation. MRI revealed a BDTT extending through the right intrahepatic bile duct to the common bile duct (Figure 3B); however, no intrahepatic recurrence was detected. A filling defect in the bile duct was noted during PTCD (Figure 3C). Because the patient had poor liver reserve and was classified in the Child-Pugh C subgroup, he underwent PTCD and TACE instead of surgery. The patient died 6 mo after PTCD and TACE due to multiple abscesses and hepatic failure.

Figure 3.

Small hepatocellular carcinoma in a 41-year-old male. A: T1-weighted MRI shows primary sHCC (arrow) in segment VI; B: A BDTT (arrows) in the right intrahepatic bile duct and the common bile duct is noted on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI; C: Filling defect (arrows) in the biliary tree is depicted during percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; sHCC: Small hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT: Bile duct tumor thrombus.

DISCUSSION

HCC has a high frequency of portal vein or/and hepatic vein invasion; however, bile duct invasion has been reported in only 0.79%-3% patients with primary HCC[11-13]. The size of primary HCC is not correlated with the occurrence of BDTT, and BDTTs may exist in patients with primary sHCC (≤ 3.0cm) and even in patients without detectable primary HCC[11,14,15]. However, BDTT occurrence after treatment of primary sHCC, which may be a new sHCC recurrence pattern, is very rare; only 1.4% (6/423) of patients with primary sHCC showed BDTTs recurrence in our study. Schmelzle et al[16] reported a case of extrahepatic growth of BDTT 3 mo after resection of multilocular HCC; however, the size of the primary multilocular HCC was not mentioned. The development of BDTT after primary sHCC treatment has not been reported in the English-language literature.

The mechanism for the emergence of HCC in the biliary system is still unknown, although the originally formed portal vein tumor thrombus may invade the bile duct via the peribiliary abundant vascular plexus or by direct invasion, or the primary HCC may rupture into the bile duct[13,17,18]. A wide ablative margin (more than 5 mm) or resection margin (2 cm) is the most important factor for local control of HCC[19,20]. In our cases, insufficient resection or ablative margins against sHCC seemed to be a risk factor for developing a BDTT after sHCC treatment because five cases had an R1 resection margin and one case had an ablative margin less than 5.0 mm. Residual microscopic tumor cells in resection margins may grow into the intrahepatic bile duct through injured bile duct walls due to hepatic resection or RFA and may extend distally to the left or right bile duct, or even the common bile duct. Interestingly, extrahepatic BDTT was reported by Schmelzle et al[16] in a patient with bile leakage after the resection of primary HCC, and BDTT development was supposed to be due to migration of cancer cells into the intrahepatic bile duct. Tumor thrombus in the portal vein was seen microscopically in the resected specimens in three cases (case 3, case 4 and case 5) in our group. A BDTT may develop via portal vein tumor thrombus invasion to the bile duct since the portal vein and bile duct are located in the same Galisson sheath[13,17,18].

Obstructive jaundice due to BDTT following sHCC treatment should be differentiated from jaundice that results from diffuse tumor recurrence infiltration, progressive hepatic failure, or hepatic hilum invasion due to intrahepatic recurrence, because the latter is often not curable, while the former may benefit from surgical resection[13]. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is valuable to detect BDTT and possible concomitant intrahepatic recurrence. As the BDTT directly connects to the intrahepatic tumor and is vascularized by the same blood supply with the intrahepatic tumor, they both show typical HCC enhancement characteristics in dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MRI, including early enhancement in the hepatic arterial phase and rapid wash-out of contrast agent in the portal vein phase[14,21,22]. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is valuable for identifying the location and extent of a BDTT[23]. It is not necessary to diagnose a BDTT using invasive methods in most cases, such as endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) and PTCD because the obstruction site or extent depicted on ERCP or PTCD is not a specific finding for the diagnosis of BDTT, and cholangitis or pancreatitis may be easily induced by these invasive methods. Obstructive jaundice in a patient with a BDTT is marked by a predominant increase in DBil, making it distinct from jaundice that results from cirrhosis and active hepatitis[13]. The serum AFP level is of limited value in the diagnosis of BDTT occurrence because AFP reflects not only tumor cell proliferation but also the activity and severity of hepatitis[24].

Obstructive jaundice would not be regarded as a contraindication of surgery[13]. The goal of therapy is removal of the BDTT and intrahepatic recurrence. A BDTT is often easy to remove, as it is not tightly adhesive to the bile duct wall. Removal of BDTT via choledochotomy and re-resection of intrahepatic recurrence may be considered in patients with adequate hepatic function[13,25]. Removal of a BDTT through resection of the extrahepatic bile duct followed by biliary-enteric anastomosis should be adopted for cases with a tumor thrombus that is tightly adhesive to the extrahepatic bile duct wall, as it indicates that the tumor thrombus has invaded the bile duct[13]. Bile duct drainage, such as endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, plastic stent placement, PTCD, or PTCD plus stent placement, should be practiced to relieve jaundice in inoperable patients, such as patients with intrahepatic recurrence at unresectable sites, multiple recurrent lesions or inadequate hepatic function. After bile duct drainage is performed, TACE may be performed to inhibit the vascularization of the recurrent tumor and the BDTT and thereby control tumor growth or even prevent fatal bile duct bleeding caused by the BDTT[13,26]. However, TACE without prior bile duct drainage is highly risky, as it may induce progressive hepatic failure[13]. Some researchers have made efforts in using liver transplant therapy to treat primary HCC associated with BDTT, but in patients with BDTT occurrence after sHCC treatment this technique has not been reported[13,27].

Many recent studies have shown that there is no significant difference in survival between HCC patients with BDTT and those without BDTT following appropriate preoperative management and aggressive surgery. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates for such patients have reached 73.3%-93.2%, 40%-56.0% and 24%-28%, respectively[13,25,28,29]. As BDTT development could lead to further deterioration of liver function, early detection and early relief of biliary system obstruction caused by tumor thrombus is an important factor to improve survival[30]. During admission, BDTTs extended to the common bile duct in all six patients in our study, which may be a negative factor leading to poor prognosis (with a mean survival time of only 11 mo).

In conclusion, BDTT occurrence is a rare, special recurrent pattern after treatment of primary sHCC. Insufficient resection or ablative margins against primary sHCC may be a risk factor for BDTT development. Patients with BDTTs extending to the common bile duct usually have unfavorable prognosis even following aggressive surgery. Early removal of BDTTs and possible concomitant intrahepatic recurrences is crucial to prolong the survival of patients.

COMMENTS

Background

Recurrence is an important unfavorable prognostic factor in small hepatocellular carcinoma (sHCC) after surgical resection or local ablation therapy. Two different sHCC recurrent patterns have been reported. Extrahepatic recurrence may extend to lymph nodes, peritoneum and extra-abdominal organs, while intrahepatic recurrence includes local recurrence, intrahepatic metastasis and multicentric carcinogenesis in the remnant liver. However, bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) occurrence is rarely reported as a recurrent pattern of primary sHCC.

Research frontiers

Bile duct invasion by primary HCC is rare, and its pathogenesis is still not completely understood. A BDTT may exist in patients with primary sHCC (≤ 3.0cm) and even in patients without detectable primary HCC. The clinicopathologic features of primary HCC with BDTT have been clarified in the literature. However, BDTT occurrence after sHCC treatment has not been reported in the English-language literature, and its clinicopathologic features have not been specified.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Six patients with BDTT occurrence after primary sHCC treatment were reported in this study, and their clinicopathologic features were reviewed. This study showed that BDTT occurrence is a rare recurrent pattern of sHCC (1.4%), and insufficient resection or ablative margins against sHCC may be a risk factor for BDTT development. Patients with BDTTs extending to the common bile duct usually have unfavorable prognosis even following aggressive surgery.

Applications

With a better understanding of the clinicopathologic features of BDTT occurrence after sHCC treatment, sufficient wide resection or ablative margins against sHCC should be performed to avoid BDTT recurrence. Early detection and removal of BDTT may be crucial to prolong the survival of patients. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of BDTT recurrence.

Terminology

BDTT formation can occur in HCC, combined hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma and liver metastasis. The mechanism for the emergence of a tumor thrombus in the biliary system is still uncertain. Patients with BDTT development are usually admitted due to obstructive jaundice, and the prognosis is generally dismal.

Peer review

In this report, Liu and colleagues provide a brief report on six patients who developed intrabiliary tumor thrombi after previous therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. This is a useful series that demonstrates that the onset of intrabiliary recurrences portends a very poor prognostic outlook. In fact, based on the survival outcomes described following treatment interventions, it could be argued that aggressive surgical intervention should not be undertaken for patients presenting with this unique pattern of recurrent disease.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Clifford S Cho, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Section of Surgical Oncology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, H4/724 Clinical Sciences Center, 600 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53792-7375, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Bosch FX. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. In: Okuda K, Tabor E, editors. Liver Cancer. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang GT, Lee PH, Tsang YM, Lai MY, Yang PM, Hu RH, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Sheu JC, Lee CZ, et al. Percutaneous ethanol injection versus surgical resection for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2005;242:36–42. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000167925.90380.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrowsky H, Busuttil RW. Resection or ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma: what is the better treatment? J Hepatol. 2008;49:502–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, Lin XJ, Lau WY. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243:321–328. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimozawa N, Hanazaki K. Longterm prognosis after hepatic resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumada T, Nakano S, Takeda I, Sugiyama K, Osada T, Kiriyama S, Sone Y, Toyoda H, Shimada S, Takahashi M, et al. Patterns of recurrence after initial treatment in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1997;25:87–92. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v25.pm0008985270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezaki T, Koyanagi N, Yamagata M, Kajiyama K, Maeda T, Sugimachi K. Postoperative recurrence of solitary small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62:115–122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199606)62:2<115::AID-JSO7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horigome H, Nomura T, Nakao H, Saso K, Takahashi Y, Akita S, Sobue S, Mizuno Y, Nojiri S, Hirose A, et al. Treatment of solitary small hepatocellular carcinoma: consideration of hepatic functional reserve and mode of recurrence. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:507–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng KK, Poon RT, Lo CM, Yuen J, Tso WK, Fan ST. Analysis of recurrence pattern and its influence on survival outcome after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi E, Maeda T, Matsumata T, Shirabe K, Kinukawa N, Sugimachi K, Tsuneyoshi M. Risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence in human small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:768–775. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin LX, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ, Fan J, Zhou XD, Sun HC, Ye QH, Wang L, Tang ZY. Diagnosis and surgical treatments of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombosis in bile duct: experience of 34 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1397–1401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i10.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh CN, Jan YY, Lee WC, Chen MF. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice due to biliary tumor thrombi. World J Surg. 2004;28:471–475. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7185-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiangji L, Weifeng T, Bin Y, Chen L, Xiaoqing J, Baihe Z, Feng S, Mengchao W. Surgery of hepatocellular carcinoma complicated with cancer thrombi in bile duct: efficacy for criteria for different therapy modalities. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:1033–1039. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu QY, Huang SQ, Chen JY, Li HG, Gao M, Liu C, Liang BL. Small hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombi: CT and MRI findings. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35:537–542. doi: 10.1007/s00261-009-9571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long XY, Li YX, Wu W, Li L, Cao J. Diagnosis of bile duct hepatocellular carcinoma thrombus without obvious intrahepatic mass. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4998–5004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmelzle M, Matthaei H, Lehwald N, Raffel A, Tustas RY, Pomjanski N, Reinecke P, Schmitt M, Schulte Am Esch J, Knoefel WT, et al. Extrahepatic intraductal ectopic hepatocellular carcinoma: bile duct filling defect. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:650–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kojiro M, Kawabata K, Kawano Y, Shirai F, Takemoto N, Nakashima T. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as intrabile duct tumor growth: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Cancer. 1982;49:2144–2147. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820515)49:10<2144::aid-cncr2820491026>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen MF, Jan YY, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Wang CS, Chen SC. Obstructive jaundice secondary to ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma into the common bile duct. Surgical experiences of 20 cases. Cancer. 1994;73:1335–1340. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940301)73:5<1335::aid-cncr2820730505>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi M, Guo RP, Lin XJ, Zhang YQ, Chen MS, Zhang CQ, Lau WY, Li JQ. Partial hepatectomy with wide versus narrow resection margin for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:36–43. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000231758.07868.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakazawa T, Kokubu S, Shibuya A, Ono K, Watanabe M, Hidaka H, Tsuchihashi T, Saigenji K. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation between local tumor progression after ablation and ablative margin. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:480–488. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabata T, Terayama N, Kobayashi S, Sanada J, Kadoya M, Matsui O. MR imaging of hepatocellular carcinomas with biliary tumor thrombi. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:470–474. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung AY, Lee JM, Choi SH, Kim SH, Lee JY, Kim SW, Han JK, Choi BI. CT features of an intraductal polypoid mass: Differentiation between hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor invasion and intraductal papillary cholangiocarcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:173–181. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q, Chen J, Li H, Liang B, Zhang L, Hu T. Hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombi: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging features to histopathologic manifestations. Eur J Radiol. 2010;76:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okuwaki Y, Nakazawa T, Shibuya A, Ono K, Hidaka H, Watanabe M, Kokubu S, Saigenji K. Intrahepatic distant recurrence after radiofrequency ablation for a single small hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors and patterns. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satoh S, Ikai I, Honda G, Okabe H, Takeyama O, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto N, Iimuro Y, Shimahara Y, Yamaoka Y. Clinicopathologic evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct thrombi. Surgery. 2000;128:779–783. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibata T, Sagoh T, Maetani Y, Ametani F, Kubo T, Itoh K, Konishi J. Transcatheter arterial embolization for bleeding from bile duct tumor thrombi of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1119–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KW, Park JW, Park JB, Kim SJ, Choi SH, Heo JS, Kwon CH, Kim DJ, Han YS, Lee SK, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct thrombi. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2093–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng SY, Wang JW, Liu YB, Cai XJ, Deng GL, Xu B, Li HJ. Surgical intervention for obstructive jaundice due to biliary tumor thrombus in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2004;28:43–46. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiomi M, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Uesaka K, Sano T, Hayakawa N, Kanai M, Yamamoto H, Nimura Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombi: aggressive operative approach after appropriate preoperative management. Surgery. 2001;129:692–698. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.113889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng BG, Liang LJ, Li SQ, Zhou F, Hua YP, Luo SM. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombi. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3966–3969. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i25.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]