Abstract

PURPOSE

Colorectal cancer studies typically include both colon and rectum tumors as a common entity, though this assumption is controversial and only minor differences have been reported at the molecular and epidemiological level. We performed a molecular study based on gene expression data of tumors from colon and rectum to assess de degree of similarity between these cancer sites at transcriptomic level.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

A pooled analysis of 460 colon tumors and 100 rectum tumors from four datasets belonging to three independent studies was performed. Microsatellite instable tumors were excluded since these are known to have a different expression profile and have a preferential proximal colon location. Expression differences were assessed with linear models and significant genes were identified using adjustment for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Minor differences at a gene expression level were found between tumors arising in the proximal colon, distal colon or rectum. Only several HOX genes were found to be associated with tumor location. More differences were found between proximal and distal colon that between distal colon and rectum.

CONCLUSIONS

Microsatellite stable colorectal cancers do not show major transcriptomic differences for tumors arising in the colon or rectum. The small but consistent differences observed are largely driven by the HOX genes. These results may have important implications in the design and interpretation of studies in colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, cancer site differences, gene expression, HOX genes

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is considered a heterogeneous complex disease that comprises different tumor phenotypes1. Attempts to classify tumors from a molecular perspective that identify carcinogenic pathways have proposed three categories with some overlap: chromosomal instability (CIN) tumors, microsatellite instability (MSI) tumors, and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) tumors. This taxonomy plays a significant role in determining clinical, pathological and biological characteristics of CRC2.

From a clinical point of view, the colon and rectal cancers are treated as distinct entities. Colon tumors are usually divided as proximal or right sided when originating proximal to the splenic flexure (cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon) whereas distal tumors arise distal to this site (descending colon and sigmoid colon). Distal colon or left sided tumors most often appear in the rectum-sigmoid flexure and the distinction of these from rectal tumors is not always easy. Usually a tumor is considered rectal when arising within 15 centimeters from the anal sphincter3,4. Indeed, accumulating evidences suggest that grouping these anatomically distinct diseases could be a clinical and biological oversimplification: rectal cancers show higher rates of locoregional relapse and lung metastases, whereas colon cancers have a higher tropism for liver spread and a slightly better overall prognosis5. Moreover, proximal location of colon cancer is a risk factor for development of metachronous colorectal cancer6. Treatment also differs for colon and rectal tumors. Although both colon and rectal cancers benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy is only indicated in locally advanced rectal tumors7. Epidemiologic risk factors reflect somewhat more controversial distinctions between cancers of the colon and rectum: alcohol intake was significantly positively associated with higher risk in the rectum than in colon tumors8. Other dietary risk factors differing between colon and rectum tumors have been suggested more inconsistently9,10.

At the molecular level, differences in expression of specific genes and proteins (Cyclin A2, COX2, beta-catenin) have been reported (reviewed in ref. 6). Moreover, colon cancers have a higher number of mutations including KRAS and BRAF mutations. The CIN pathway is far more common in rectal cancers than colon cancers, whereas MSI and CIMP cancers are more likely to be in the right colon. Some of the reported differences in gene expression probably correspond to molecular signatures of MSI, such as the correlation between CDX2 expression and MSI11.

Recently, several molecular profiles have been proposed to predict prognosis in CRC patients12-15. These studies typically combine colon and rectal cancers, but it is not known whether this combination is appropriate. Expression profiles may inform this choice. If proximal colon, distal colon and rectal tumors share a common set of expressed transcripts, then it may be reasonable to combine data for prognostic studies, and in fact may inform choices for epidemiologic study designs. The aim of this work was to compare gene expression among colorectal cancer sub-sites in an attempt to identify molecular factors that correspond to differences in the clinical behavior of these tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The Molecular Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer (MECC) study is a population-based, case-control study that included 2,138 incident CRC cases and 2,049 population controls from Northern Israel16. A pathology review of the diagnostic slides centralized at the University of Michigan confirmed the eligibility criteria of invasive adenocarcinoma. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Michigan and Carmel Medical Center in Haifa. Written, informed consent was required for inclusion.

A subset of these patients provided fresh tumor tissue samples that were analyzed for expression in two stages as previously described17. Initially, a subset of 170 tumors was hybridized with the Affymetrix HG-U133A gene array (MECC-A). In a second stage, an additional sample of 232 tumors was hybridized in the HG-U133plus 2.0 gene array (MECC-P2). Of these patients, four from the first set and seven from the second were excluded because had multiple tumors in the colon and rectum or the precise location was not provided. Expression data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)18 repository with accession code GSE26682.

In addition of these two gene expression datasets (MECC-A and MECC-P2), publicly available expression data with information about sub-site was searched in the GEO and ArrayExpress19 databases. To guarantee a high-quality analysis, the inclusion criteria was restricted to studies that had used Affymetrix U133 gene chips, with more than 50 samples, and a minimum number of 10 for each site. Two datasets were identified matching these criteria: GSE14333 included 290 consecutive CRC patients (250 colon, 39 rectum, 1 missing site)20. GSE13294 comprised 155 CRC patients (122 colon, 25 rectum, 8 missing) 21. Additionally, dataset GSE9254 was identified, that included 19 normal mucosa samples from different colonic locations: cecum (2), ascending (3), transverse (3), sigmoid (4) and rectum (7) 22.

Quality control and normalization

Prior to data analysis a careful quality control process following the Affymetrix recommendations was performed23. This procedure rejected 122 samples: 27 (16%) from MECC-A, 49 (21%) from MECC-P2, 21 (7%) from GSE14333 and 25 (16%) from GSE13294.

Data normalization was performed using the R statistical software, version 2.9.0 (R foundation for statistical computing; http://www.r-project.org) and Bioconductor package (Bioconductor core group; http://www.bioconductor.org). Raw data from the different datasets were normalized together using the Robust Multiarray Average (RMA) method24. In order to improve comparability between arrays from different studies, only the common subset of probes from the U133A array (n= 22,283) were selected and data were renormalized using a quantile method.

Microsatellite instability

Tumors showing MSI appear more often in right colon and are known to have a marked different expression profile25. In an attempt to homogenize the analysis and avoid potential biases due to this condition MSI tumors were excluded from all datasets. For MECC cases MSI was analyzed using seven microsatellite markers that included the NCI panel26. Cases were considered MSI when more than 30% of the markers were instable. 16 cases were excluded from MECC-A and 15 from MECC-P2. 61 MSI samples from dataset GSE1324 were also excluded.

MSI status was not available for the public GSE14333 dataset, but was imputed using a molecular profiling based approach (details in supplementary material table I and figure 1). Out of the 268 samples, 53 (20%) were labeled as MSI and removed for further analysis. These excluded cases might not be a perfect selection of the real subset of MSI tumors, but their clinical characteristics are in agreement with the expectations: more frequent in female and older patients, and with preferential location in right colon (supplementary table 2).

Differential expression analysis

Prior to the identification of differentially expressed probes, a filter was applied in order to remove those with low variability (n=7,509), which mostly correspond to non-hybridized and saturated probes. The remaining 14,774 probes with standard deviation greater than 0.3 were considered for further analysis. In order to test for differences in expression between sites, a linear model adjusted for gender, age and study was fitted to each probe. To account for multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction was used. Also the less conservative q-value method was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR).

Heterogeneity of expression profiles by tumor site across studies was evaluated for each probe using the linear models described above. A test for interaction between cancer site and study was performed for each probe and, again, the q-value method was used to correct the results by multiple comparisons.

Gene set enrichment analysis

The GSEA algorithm27 was applied to identify enrichment of specific functions in the list of genes pre-ranked according to their p value for the test of differences in expression between sub-sites. The statistical significance of the enrichment score was calculated by permuting the genes 1,000 times as implemented in the GSEA software.

Classification of colon / rectum samples using differentially expressed genes

For each comparison considered, an agglomerative hierarchical clustering method was used in order to display the classification ability among site of the corresponding list of differentially expressed probes sets. This discriminating ability was formally tested using a linear discriminant analysis with leave-one-out cross-validation to estimate the prediction error rate.

RESULTS

Clinical data for the 460 colon tumors and 100 rectum tumors included in the analysis are summarized in Table I. A principal component analysis (PCA) was done to assess global differences between each dataset. The first and second components separated the samples by study, suggesting systematic differences that could not be corrected by careful homogeneous criteria and normalization (Supplementary Figure 2). The most dissimilar dataset was MECC-A, probably due to be the fact that the platform was Affymetrix H-U133 A gene chips, instead of H-U133 Plus 2.0 used in the other studies. All pooled analyses were adjusted for study to account for these systematic differences.

Table I.

Samples description

| n = 560 | Site* | Platform | Mean age |

Gender** | Stage** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| right | left | rectum | male | female | I | II | III | IV | |||

|

MECC-A

n = 123 |

55 (44.7%) |

57 (46.4%) |

11 (8.9%) |

Affy HG- U133A |

72.53 | 68 (55.3%) |

55 (44.7%) |

4 (3.4%) |

58 (50%) |

41 (35.4%) |

13 (11.2%) |

|

MECC-P2

n = 161 |

58 (36.9%) |

59 (37.6%) |

40 (25.5%) |

Affy U133 Plus 2.0 |

72.01 | 87 (54%) |

74 (46%) |

20 (15.4%) |

55 (42.3%) |

39 (30%) |

16 (12.3%) |

|

GSE14333

n = 215 |

79 (37.1%) |

100 (46.9%) |

34 (16%) |

Affy U133 Plus 2.0 |

65.65 | 132 (61.4%) |

83 (38.6%) |

34 (15.8%) |

61 (28.4%) |

64 (29.8%) |

56 (26%) |

|

GSE13294

n = 61 |

46 (75.4%) |

15 (24.6%) |

Affy U133 Plus 2.0 |

65.43 | 32 (53.3%) |

28 (46.7%) |

0 (0%) |

46 (75.4%) |

7 (11.5%) |

8 (13.1%) |

|

Some cases were classified as “colon” with no information about specific sub-site

Number may not add to total due to missing information

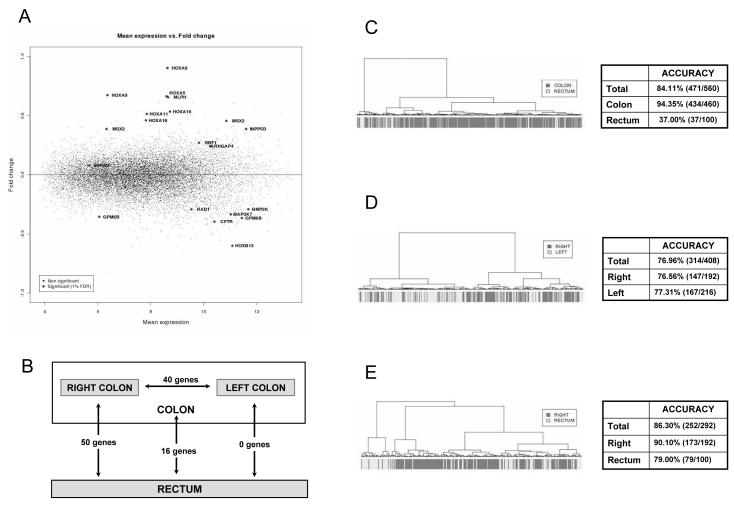

Gene expression profiling: colon versus rectum tumors

Linear models adjusted for study, age and gender identified only 11 out of 14,774 differentially expressed probes between colon and rectum after Bonferroni correction. The less conservative q-value method identified 20 probes (corresponding to 16 genes, Table II) when a 1% FDR was used, and 131 probes (111 genes) at the 5% FDR. Moreover, among these differentially expressed genes, no one had an absolute log2 fold change larger than 1 (Figure 1 A). These results suggest that the magnitude of expression differences among microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors arising in the colon and rectum is quite small.

Table II.

Differentially expressed genes between colon and rectum tumors

| Probe | Gen | q value | Log2 Fold Change |

Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 209844_at | HOXB13 | 3,65E-06 | −0,600 | Transcription factor activity |

| 213823_at | HOXA11 | 5,91E-06 | 0,514 | Transcription factor activity |

| 209167_at | GPM6B | 1,88E-05 | −0,355 | Cell differentiation |

| 209170_s_at | 3,15E-03 | −0,366 | ||

| 214651_s_at | HOXA9 | 2,32E-05 | 0,902 | Transcription factor activity |

| 209905_at | 5,08E-05 | 0,673 | ||

| 213147_at | HOXA10 | 2,99E-05 | 0,460 | Transcription factor activity |

| 213150_at | 2,68E-04 | 0,534 | ||

| 213844_at | HOXA5 | 2,40E-04 | 0,663 | Transcription factor activity |

| 39835_at | SBF1 | 3,20E-04 | 0,270 | Protein amino acid dephosphorylation |

| 218211_s_at | MLPH | 2,52E-03 | 0,655 | Melanosome transport |

| 216629_at | SRRM2 | 2,78E-03 | 0,079 | RNA splicing |

| 205555_s_at | MSX2 | 2,89E-03 | 0,387 | Transcription factor activity |

| 210319_x_at | 3,15E-03 | 0,455 | ||

| 204461_x_at | RAD1 | 3,15E-03 | −0,292 | DNA repair |

| 59644_at | BMP2K | 3,65E-03 | −0,291 | Protein amino acid phosphorylation |

| 215703_at | CFTR | 5,60E-03 | −0,396 | Transmembrane transport |

| 204425_at | ARHGAP4 | 7,13E-03 | 0,242 | Apoptosis |

| 203332_s_at | INPP5D | 7,47E-03 | 0,387 | Apoptosis |

| 206854_s_at | MAP3K7 | 9,86E-03 | −0,335 | Signal transduction |

Figure 1. Fold change plot and prediction ability of site-related differentially expressed genes.

Mean expression of each probe set versus its fold change between colon and rectum tumors (A). Number of differentially expressed genes between each tumoral location at FDR 1% (B). Dendrogram illustrating the classification ability of differentially expressed genes among site in colon versus rectum (C), right versus left (D) and right versus rectum (E). Companion tables show the accuracy of each study.

Functionally, it was noteworthy that five of the top six genes belonged to the HOX family of transcription factors (Table II). Other top differentially expressed genes displayed assorted functions such as DNA repair, transcription factor activity, intracellular transport, signal transduction and apoptosis among others. To formally identify enriched biological processes associated with differentially expressed genes a GSEA was done. Although no significant function was retrieved, the “HOX genes” set appeared with the highest gene enrichment score (Supplementary Figure 3).

Heterogeneity across studies was explored to identify genes that might have differences in some studies but opposite direction in others that might compensate in the pooled analysis. Only 12 probes showed heterogeneity between studies at the 5% FDR and these could not be ascribed to a systematic effect of one specific study (Supplementary Figure 4). None of these 12 heterogeneous probes corresponded to differentially expressed genes. Therefore, the four studies included in our analysis were considered homogeneous regarding their differences in expression profiles between colon and rectum.

Refining gene expression profiling: right colon versus left colon tumors and right colon versus rectum tumors

To discount the possibility that similar molecular backgrounds in left colon and rectum tumors were masking possible differences between total colon samples and rectum tumors, a more detailed analysis was performed looking for differences between right colon, left colon and rectum tumors, when detailed data about cancer site were available (n = 499, all datasets except GSE13294).

Similar to previous results, no major differences were detected between right and left colon, reinforcing our impression that microsatellite stable colorectal tumors show very similar expression profiles regardless of their site of origin. Ten genes were found to be differentially expressed between right and left colon tumors after Bonferroni correction. The q-value method only identified 44 probes differentially expressed corresponding to 40 genes at 1% FDR (Table III) and 174 probes (150 genes) at 5% FDR. Interestingly, the comparison between left colon and rectum did not identify any differentially expressed gene at 1% FDR (only 3 genes were found at FDR 5%). In contrast, 54 probes (50 genes) were differentially expressed between right-colon and rectum when a 1% FDR was used (Table IV) and 374 probes (324 genes) at the 5% FDR. From those, 21 probes (18 genes) passed Bonferroni correction (Figure 1 B). Functionally, those genes showed varied functions, highlighting the HOX family as in previous analysis.

Table III.

Differentially expressed genes between right and left colon

| Probe | Gen | q value | Log2 Fold Change |

Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 206858_s_at | HOXC6 | 2,04E-08 | 0,868 | Transcription factor activity |

| 209844_at | HOXB13 | 1,18E-06 | −0,521 | Transcription factor activity |

| 219109_at | SPAG16 | 6,11E-05 | −0,703 | Cell projection |

| 205767_at | EREG | 1,47E-04 | −1,082 | Growth factor activity |

| 206307_s_at | FOXD1 | 2,50E-04 | 0,434 | Transcription factor activity |

| 209524_at | HDGFRP3 | 2,76E-04 | −0,678 | Growth factor activity |

| 209526_s_at | 6,17E-04 | −0,512 | ||

| 216693_x_at | 6,31E-04 | −0,496 | ||

| 203988_s_at | FUT8 | 1,62E-03 | 0,308 | N-glycan processing |

| 205555_s_at | MSX2 | 2,01E-03 | 0,393 | Transcription factor activity |

| 210319_x_at | 8,60E-03 | 0,440 | ||

| 209752_at | REG1A | 2,01E-03 | 1,263 | Growth factor activity |

| 217918_at | DYNLRB1 | 3,16E-03 | −0,212 | Microtubule-based movement |

| 212423_at | ZCCHC24 | 3,63E-03 | −0,406 | Nucleic acid binding |

| 212419_at | 9,56E-03 | −0,322 | ||

| 219228_at | ZNF331 | 3,63E-03 | −0,316 | Transcription factor activity |

| 219955_at | L1TD1 | 3,82E-03 | 0,878 | Transposase |

| 207457_s_at | LY6G6D | 4,19E-03 | −0,786 | --- |

| 218094_s_at | DBNDD2 | 4,30E-03 | −0,254 | Regulation of protein kinase activity |

| 217665_at | --- | 5,11E-03 | −0,247 | --- |

| 202925_s_at | PLAGL2 | 5,56E-03 | −0,334 | Transcription factor activity |

| 208948_s_at | STAU1 | 5,56E-03 | −0,171 | RNA binding |

| 217801_at | ATP5E | 5,56E-03 | −0,138 | ATP synthesis |

| 212349_at | POFUT1 | 5,98E-03 | −0,252 | Notch signalling pathway |

| 204819_at | FGD1 | 6,02E-03 | −0,201 | Signal transduction |

| 205815_at | REG3A | 7,19E-03 | 1,011 | Cell proliferation |

| 206340_at | NR1H4 | 7,19E-03 | 0,177 | Transcription factor activity |

| 208979_at | NCOA6 | 7,94E-03 | −0,194 | Transcription regulation |

| 201998_at | ST6GAL1 | 8,51E-03 | −0,409 | Protein amino acid glycosylation |

| 202673_at | DPM1 | 8,51E-03 | −0,239 | Protein binding |

| 217718_s_at | YWHAB | 8,60E-03 | −0,138 | Signal transduction |

| 204555_s_at | PPP1R3D | 8,82E-03 | −0,260 | Protein binding |

| 205463_s_at | PDGFA | 8,82E-03 | −0,323 | Growth factor activity |

| 205997_at | ADAM28 | 8,82E-03 | 0,295 | Proteolysis |

| 212234_at | ASXL1 | 8,82E-03 | −0,200 | Regulation of transcription |

| 212787_at | YLPM1 | 8,82E-03 | 0,141 | Regulation of transcription |

| 213170_at | GPX7 | 8,82E-03 | −0,287 | Response to oxidative stress |

| 214482_at | ZBTB25 | 8,82E-03 | 0,131 | Transcription factor activity |

| 215210_s_at | DLST | 8,82E-03 | 0,238 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| 218325_s_at | DIDO1 | 8,82E-03 | −0,241 | Apoptosis |

| 219108_x_at | DDX27 | 8,82E-03 | −0,188 | RNA binding |

| 221472_at | SERINC3 | 8,82E-03 | −0,190 | Protein binding |

| 204015_s_at | DUSP4 | 9,56E-03 | 0,368 | Signal transduction |

| 203127_s_at | SPTLC2 | 9,79E-03 | 0,199 | Lipid metabolism |

Table IV.

Differentially expressed genes between right colon and rectum tumors

| Probe | Gen | q value | Log2 Fold Change |

Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 209844_at | HOXB13 | 3,51E-09 | −0,856 | Transcription factor activity |

| 205555_s_at | MSX2 | 4,30E-05 | 0,586 | Transcription factor activity |

| 210319_x_at | 7,11E-05 | 0,696 | ||

| 213823_at | HOXA11 | 4,30E-05 | 0,590 | Transcription factor activity |

| 214651_s_at | HOXA9 | 4,30E-05 | 1,013 | Transcription factor activity |

| 209905_at | 3,98E-04 | 0,748 | ||

| 206858_s_at | HOXC6 | 8,90E-05 | 1,057 | Transcription factor activity |

| 218211_s_at | MLPH | 9,10E-05 | 0,856 | ROS metabolism |

| 213844_at | HOXA5 | 1,02E-04 | 0,806 | Transcription factor activity |

| 213150_at | HOXA10 | 1,77E-04 | 0,590 | Transcription factor activity |

| 213147_at | 6,82E-04 | 0,509 | ||

| 39835_at | SBF1 | 1,77E-04 | 0,343 | Protein amino acid dephosphorylation |

| 211756_at | PTHLH | 8,02E-04 | −0,167 | Hormone activity |

| 206854_s_at | MAP3K7 | 8,77E-04 | −0,408 | Signal transduction |

| 219109_at | SPAG16 | 9,80E-04 | −0,858 | Cell projection |

| 214598_at | CLDN8 | 9,93E-04 | −0,722 | Cell adhesion |

| 209167_at | GPM6B | 1,15E-03 | −0,389 | Cell differentiation |

| 204425_at | ARHGAP4 | 1,18E-03 | 0,334 | Apoptosis |

| 36554_at | ASMTL | 1,36E-03 | 0,263 | Melatonin biosynthesis |

| 204667_at | FOXA1 | 1,43E-03 | 0,481 | Transcription factor activity |

| 204042_at | WASF3 | 1,44E-03 | −0,660 | Actin binding |

| 203699_s_at | DIO2 | 1,69E-03 | −0,281 | Hormone biosynthesis |

| 213927_at | MAP3K9 | 1,69E-03 | 0,130 | Signal transduction |

| 211737_x_at | PTN | 1,92E-03 | −0,240 | Growth factor activity |

| 209465_x_at | 2,34E-03 | −0,367 | ||

| 212840_at | UBXN7 | 2,34E-03 | −0,501 | Protein binding |

| 210766_s_at | CSE1L | 2,70E-03 | −0,396 | Protein transport |

| 215703_at | CFTR | 2,70E-03 | −0,441 | Respiratory gaseous exchange |

| 216129_at | ATP9A | 2,70E-03 | −0,458 | ATP biosynthesis |

| 212234_at | ASXL1 | 3,21E-03 | −0,257 | Regulation of transcription |

| 218454_at | PLBD1 | 3,57E-03 | −0,375 | Lipid degradation |

| 205423_at | AP1B1 | 4,08E-03 | 0,204 | Protein transport |

| 206070_s_at | EPHA3 | 4,59E-03 | −0,421 | Receptor |

| 203628_at | IGF1R | 4,83E-03 | −0,544 | Receptor |

| 202949_s_at | FHL2 | 4,98E-03 | 0,347 | Transcription regulation |

| 221738_at | KIAA1219 | 4,98E-03 | −0,229 | Signal transduction |

| 202760_s_at | PALM2 | 5,30E-03 | −0,503 | Regulation of cell shape |

| 219228_at | ZNF331 | 5,30E-03 | −0,218 | Regulation of transcription |

| 219426_at | EIF2C3 | 6,45E-03 | −0,486 | RNA binding |

| 214234_s_at | CYP3A5 | 6,64E-03 | 0,437 | Electron carrier activity |

| 218892_at | DCHS1 | 6,64E-03 | −0,162 | Cell adhesion |

| 222015_at | CSNK1E | 6,67E-03 | 0,321 | Signal transduction |

| 209195_s_at | ADCY6 | 6,76E-03 | 0,260 | Signal transduction |

| 215078_at | SOD2 | 7,65E-03 | −0,363 | Removal of superoxide radicals |

| 203671_at | TPMT | 7,85E-03 | −0,238 | Metabolism of thiopurine drugs |

| 205767_at | EREG | 7,85E-03 | −1,211 | Growth factor activity |

| 221091_at | INSL5 | 7,85E-03 | −0,406 | Hormone activity |

| 202925_s_at | PLAGL2 | 7,88E-03 | −0,395 | Transcription factor activity |

| 213242_x_at | KIAA0284 | 8,06E-03 | 0,327 | Microtubule organization |

| 202673_at | DPM1 | 8,45E-03 | −0,240 | Protein binding |

| 219955_at | L1TD1 | 8,47E-03 | 1,064 | Transposase |

| 201978_s_at | KIAA0141 | 8,75E-03 | 0,300 | --- |

| 32069_at | N4BP1 | 8,75E-03 | −0,220 | Protein binding |

| 211843_x_at | CYP3A7 | 9,25E-03 | 0,367 | Electron carrier activity |

To assess the ability of these profiles to discriminate cancer samples by location, a linear discriminant analysis model was built. Leave-one out internal validation showed that only 37% of rectum tumors were correctly classified when using the colon versus rectum signature (Figure 1 C). Better performance was obtained using the right versus left signature, with 77% accuracy both in right and left tumors (Figure 1 D). The best classification was achieved using the right versus rectum tumors profile (with a total accuracy of 86%) indicating that the major differences exist between the most opposite locations (Figure 1 E).

Since classification of rectal tumors is controversial and misclassification could exist between rectal and sigmoid colon tumors, an analysis in which rectal and left-sided colon cancers were pooled and compared with right-sided colon cancer was also performed. As a result, 46 probes corresponding to 35 genes were found to be differentially expressed after Bonferroni correction. The q-value method identified 256 probes (202 genes) differentially expressed at 1% FDR (Supplementary Table III) and 884 probes at 5% FDR. Though this comparison showed a larger number of significant probes, related to the increased sample size of the distal location group, the magnitude of the differences were very small (<10%) and probably not biologically relevant.

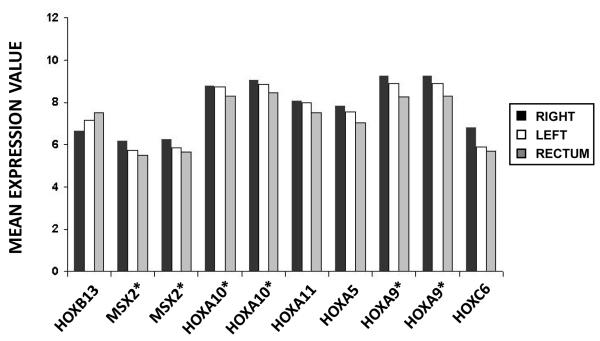

HOX genes

Remarkably, HOX appeared as the most differentially expressed genes in all transcriptomic comparisons and emerged in the intersection of the lists of differentially expressed genes. In fact, these HOX genes were expressed in a gradient in colorectal tumors. The HOX genes were more expressed in tumors from the proximal colon and their expression decreased along more distal locations in the gastrointestinal tract, with the exception of HOXB13 that showed a reversed pattern (Figure 2). Genes known to be targets of HOX transcription factors28 were analyzed, but these showed no differences in expression between sub-sites indicating that differences observed in HOX genes were not affecting a cascade of regulated genes (Supplementary Figure 5). Also, specific GSEA analysis using HOX-related gene sets showed a statistically significant enrichment for genes activated by the chimeric protein NUP98-HOXA9, an aberrant HOX transcription factor and also and enrichment in genes with promoter regions around transcription start site containing the motif that binds with HOX9 (Supplementary Table IV).

Figure 2. HOX genes reverse gradient of expression along colorectal tumor locations.

Mean expression value of HOX genes in right colon, left colon and rectum tumors. Genes marked with an asterisk are represented in the microarray by more than one probe set.

Interestingly, the analysis of expression for HOX genes in human normal colorectal mucosa in the dataset GES9254 showed the same gradient along the gut than in tumor samples (Supplementary Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

This pool analysis of four datasets from three independent studies including a total of 560 samples suggests that there are identifiable expression differences among microsatellite stable CRCs that arise in different sites within the large intestine. However, the number of statistically significant differentially expressed genes found between tumor locations was minimal, and the fold change of their expression was within random variation for most cases. With the exception of the HOX family, there were no identifiable functional distinctions among the differentially expressed genes. Moreover, the most evident distinctions in expression profiles were those between the right colon and either the left colon or rectum. Expression profiles of microsatellite stable rectal cancers and right-sided colon cancers were virtually indistinguishable.

These results imply that anatomical differences are relevant for the clinical management of colorectal cancer, but those specific molecular profiles of microsatellite stable CRC are for the large part, quite similar. It is well known that metastases from colorectal cancer develop in a stepwise process29. Rectal cancers usually have a pattern of local recurrence and retrospective studies show a relevant influence of the surgeon on the prognosis of these patients30. For colon cancers, the progression pattern is more typically characterized by liver metastases, potentially explained by the fact that superior mesenteric vein drains the right colon whereas neither the left colon nor the rectal vasculature directly drains to liver29. One might have hypothesized that molecular differences such as DNA repair, apoptosis or angiogenesis might have distinguished rectal cancers, given the differential efficacy of radiotherapy for rectal cancers. However our study did not reveal any such clues or signatures. The samples that were analyzed were all tumors collected prior to treatment. Although it is possible that expression profiles that predict response to radiotherapy might exist, our pre-treatment data are unable to address this hypothesis. In addition, there is no known evidence of differential radiation sensitivity between colon and rectal cancers. It is only the particular topographic intrapelvic location of the rectum that renders it appropriate for radiotherapy due to the lack of small bowel interaction with the radiation field, which is the limiting factor of the radiotherapy administration in colon cancer31, 32. A potential concern of studies that fail to detect differences in expression patterns between tumors is the possibility of insufficient statistical power to detect even clinically or biologically meaningful differences due to a small sample size. To address this issue a pooled analysis has been performed that included a total of 560 samples, enough to detect 0.5 standard deviation units. In practice, most of the few significant genes identified showed fold changes smaller than 0.6 or a 50% variation in expression, which is usually considered small in microarray expression analyses. Small studies also may show apparent differences that are particular to the selection of cases analyzed. The strength of meta-analyses like the one reported here is that only consistent results remain, and these are easily identified since power is larger and heterogeneity can be explored to identify study specificities. In our analysis heterogeneity among studies was not a concern since only 12 probes, out of almost 15,000 explored, showed significant heterogeneity and they could not be ascribed to a specific study.

MSI tumors were not included in the analysis due to their known different molecular background21,25,33 and strong association with tumor location. In the case of GSE14333 dataset, the researchers did not provide information about MSI status so a simple signature-based imputation was done to exclude putative MSI tumors from the analysis. This procedure had its limitations since its accuracy for MSI was only 85% (Supplementary Table I). Thus more MSS tumors than necessary may have been excluded, and some MSI cancers from GSE14333 may have been inadvertently included by our simple imputation. This strategy of attempting to eliminate MSI colorectal cancers was preferred to the alternative design that would have resulted in a strong biased estimation, or a choice to completely exclude all 215 of the otherwise informative tumors from GSE14333. A choice to exclude these tumors would have further reduced the power to detect any possible existing differences. It is reassuring to note that tumors excluded from the analysis had clinical features related to MSI, such as a predominance of female and older patient that originate in the colon, mainly in the right side (Supplementary Table II)34. Additionally, an analysis excluding GSE14333 dataset was performed and similar results (still less significant genes) were obtained (Supplementary Table V).

It is worth mentioning that differences between cancer sites previously reported in some studies may be related to MSI status: Komuro et al. found gene expression differences between right and left-sided colorectal cancers in genes related to MSI such as MSH2 in right-sided tumors35. A similar work by Birkenkamp-Demtroder et al. also reported differences between 25 MSS and MSI right and left tumors36. Watanabe et al. describes small differences between proximal and distal MSI colorectal tumors37. These differences are probably related to the combination of MSI and MSS tumors. CDX2 has been reported to be more expressed in proximal structures than distal11 but we didn’t found it as a right-side associated gen. However, if we include in our analysis MSI tumors and look for CDX2 expression, it appeared as a differentially expressed gen with a q-value < 0.01. So, the significance of CDX2 is probably due to MSI and not to tumor location.

Although most of CIMP-positive tumors are MSI and therefore were not included in this analysis, there are some CIMP-positive, microsatellite stable tumors that preferentially arise in the right colon2,38 which could explain some of the larger differences between the tumors arising in the right colon and other tumors. In an attempt to explore this possibility, a gene expression signature that differentiates MSS CIMP+ and MSS CIMP− colorectal carcinomas was used39 in a GSEA analysis. This revealed an association between CIMP+ genes and right-sided genes (supplementary figure 7) and suggests that some of the described differences could be related to CIMP phenotype.

Only HOX genes were found to be an enriched set associated with colon tumors. These genes (also known as homeobox genes) encode transcription factors that play essential roles in controlling cell growth and differentiation during embryonic and normal tissue development. Many homeobox genes have been reported to be de-regulated in a variety of solid tumors including CRC and also to vary between normal mucosa and colorectal cancer tissue40,41. Interestingly, differences in HOX expression between carcinomas from the right colon and left colon have been reported previously42. In normal human intestinal mucosa, HOX-A genes are widely expressed in undifferentiated proliferating cells at the base of the crypts43. So, we speculate that HOX expression in colon tumors could be an amplification of the signal from colon cancer stem cell that drives intestinal cell differentiation. Since HOX expression patterns along the gut reflect pivotal roles of these genes in the regional regenerative process of the epithelial cells44, it is possible that our results simply mirrors the HOX expression pattern maintained in tumors as it usually is in the normal mucosa. In fact, we observed the same gradient of expression in normal mucosa along the gut (Supplementary Figure 6). However, despite our analysis showed no differential expression among genes targeted by HOX, enrichment in genes activated by NUP98-HOXA9 was found. This is an aberrant HOXA9 transcription factor that promotes the growth of murine hematopoietic progenitors and blocks their differentiation45. This result might be related to a possible role of HOX genes in CRC right-side tumor progression that deserves experimentally exploration.

In conclusion, our study strongly suggests that the expression profiles of microsatellite stable colorectal cancers do not demonstrate major differences for tumors arising in the colon or rectum, and that the small, but consistent differences observed between right-sided and left-sided / rectal cancers are largely driven by the HOX family of genes. Although it is clear that diverse somatic mutations that characterize individual cancers suggest the possibility for targeted therapies to be developed for each individual cancer in each patient, our data demonstrate that colorectal cancers, on average, show few differences based on tumor location. This observation could have important clinical implications in terms of prognostic analysis, biomarker discovery or drug development.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Colorectal cancer studies typically include both colon and rectum tumors as a common entity, though this assumption is controversial and only minor differences have been reported at the molecular and epidemiological level. Here we report a large sample pool study concluding that only minor differences at a gene expression level exist between microsatellite stable colorectal cancers at different locations. These results have important implications in the design and interpretation of studies in colorectal cancer. For instance, several molecular profiles have been recently proposed to predict prognosis in CRC patients that combine colon and rectum cases assuming this hypothesis without the real proof. The conclusions provided by this study will help consolidate the idea that at the molecular level, the minor expression differences identified are more related to anatomical developmental differences than to tumoral mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This study was supported by a grant (1R01CA81488) from the National Cancer Institute. Also the Catalan Institute of Oncology and the Private Foundation of the Biomedical Research Institute of Bellvitge (IDIBELL), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grants PI08-1635, PI08-1359, PS09-1037), CIBERESP CB06/02/2005 and the “Acción Transversal del Cancer”, the Catalan Government DURSI grant 2009SGR1489, the European Commission grant FP7-COOP-Health-2007-B “HiPerDART” and the AECC (Spanish Association Against Cancer) Scientific Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(25):2449–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10(1):13–27. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iacopetta B. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer? Int J Cancer. 2002;101(5):403–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bufill JA. Colorectal cancer: evidence for distinct genetic categories based on proximal or distal tumor location. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(10):779–88. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-10-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan KK, Gde L Lopes, Jr., Sim R. How uncommon are isolated lung metastases in colorectal cancer? A review from database of 754 patients over 4 years. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(4):642–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li FY, Lai MD. Colorectal cancer, one entity or three. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009;10(3):219–29. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casillas S, Pelley RJ, Milsom JW. Adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer: present and future perspectives. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(8):977–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02051209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermann S, Rohrmann S, Linseisen J. Lifestyle factors, obesity and the risk of colorectal adenomas in EPIC-Heidelberg. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(8):1397–408. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Wu K, Rosner B, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, et al. Comparison of risk factors for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(3):433–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terry P, Giovannucci E, Michels KB, Bergkvist L, Hansen H, Holmberg L, et al. Fruit, vegetables, dietary fiber, and risk of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(7):525–33. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.7.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozek LS, Lipkin SM, Fearon ER, Hanash S, Giordano TJ, Greenson JK, et al. CDX2 polymorphisms, RNA expression, and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(13):5488–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritzmann J, Morkel M, Besser D, Budczies J, Kosel F, Brembeck FH, et al. A colorectal cancer expression profile that includes transforming growth factor beta inhibitor BAMBI predicts metastatic potential. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):165–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamasaki M, Takemasa I, Komori T, Watanabe S, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, et al. The gene expression profile represents the molecular nature of liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;30(1):129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuyama T, Ishikawa T, Mogushi K, Yoshida T, Iida S, Uetake H, et al. MUC12 mRNA expression is an independent marker of prognosis in stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(10):2292–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25256. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salazar R, Roepman P, Capella G, Moreno V, Simon I, Dreezen C, et al. Gene expression signature to improve prognosis prediction of stage II and III colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):17–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poynter JN, Gruber SB, Higgin PD, Almog R, Bonner JD, Rennert HS, Low M, Greenson JK, Rennert G. Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(21):2184–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilar E, Bartnik CM, Stenzel SL, Raskin L, Ahn J, Moreno V, et al. MRE11 deficiency increases sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition in microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2632–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1120. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett T, Edgar R. Gene expression omnibus: microarray data storage, submission, retrieval, and analysis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:352–69. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parkinson H, Kapushesky M, Shojatalab M, Abeygunawardena N, Coulson RA, Holloway E, et al. ArrayExpress--a public database of microarray experiments and gene expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D747–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorissen RN, Gibbs P, Christie M, Prakash S, Lipton L, Desai J, et al. Metastasis-Associated Gene Expression Changes Predict Poor Outcomes in Patients with Dukes Stage B and C Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(24):7642–7651. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorissen RN, Lipton L, Gibbs P, Chapman M, Desai J, Jones IT, et al. DNA copy-number alterations underlie gene expression differences between microsatellite stable and unstable colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(24):8061–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaPointe LC, Dunne R, Brown GS, Worthley DL, Molloy PL, Wattchow D, et al. Map of differential transcript expression in the normal human large intestine. Physiol Genomics. 2008;33(1):50–64. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00185.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Affymetrix, Inc. GeneChip Expression Analysis – Data Analysis Fundamentals. 2002 http://media.affymetrix.com/support/downloads/manuals/data_analysis_fundamentals_manual.pdf.

- 24.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim H, Nam SW, Rhee H, Li L Shan, Ju Kang H, Koh K Hye, et al. Different gene expression profiles between microsatellite instability-high and microsatellite stable colorectal carcinomas. Oncogene. 2004;23(37):6218–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozek LS, Herron CM, Greenson JK, Moreno V, Capella G, Rennert G, et al. Smoking, gender, and ethnicity predict somatic BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(3):838–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svingen T, Tonissen K. Hox transcription factors and their elusive mammalian gene targets. Heredity. 2006;97(2):88–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugarbaker PH. Metastatic inefficiency: the scientific basis for resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol Suppl. 1993;3:158–60. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930530541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Cataldo A, Scilletta B, Latino R, Cocuzza A, Li Destri G. The surgeon as a prognostic factor in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2007;16(Suppl 1):S53–6. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aleman BM, Bartelink H, Gunderson LL. The current role of radiotherapy in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A(7-8):1333–9. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00280-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foroudi F, Tyldesley S, Barbera L, Huang J, Mackillop WJ. An evidence-based estimate of the appropriate radiotherapy utilization rate for colorectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(5):1295–307. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunican DS, McWilliam P, Tighe O, Parle-McDermott A, Croke DT. Gene expression differences between the microsatellite instability (MIN) and chromosomal instability (CIN) phenotypes in colorectal cancer revealed by high-density cDNA array hybridization. Oncogene. 2002;21(20):3253–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakar S, Burgart LJ, Thibodeau SN, Rabe KG, Petersen GM, Goldberg RM, et al. Frequency of loss of hMLH1 expression in colorectal carcinoma increases with advancing age. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1421–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komuro K, Tada M, Tamoto E, Kawakami A, Matsunaga A, Teramoto K, et al. Right- and left-sided colorectal cancers display distinct expression profiles and the anatomical stratification allows a high accuracy prediction of lymph node metastasis. J Surg Res. 2005;124(2):216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birkenkamp-Demtroder K, Olesen SH, Sorensen FB, Laurberg S, Laiho P, Aaltonen LA, et al. Differential gene expression in colon cancer of the caecum versus the sigmoid and rectosigmoid. Gut. 2005;54(3):374–84. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.036848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe T, Kobunai T, Toda E, Yamamoto Y, Kanazawa T, Kazama Y, et al. Distal colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability (MSI) display distinct gene expression profiles that are different from proximal MSI cancers. Cancer Res. 2006;66(20):9804–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtin K, Slattery ML, Samowitz WS. CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer: past, present and Future. Patholog Res Int. 2011:902674. doi: 10.4061/2011/902674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferracin M, Gafà R, Miotto E, Veronese A, Pultrone C, Sabbioni S, et al. The methylator phenotype in microsatellite stable colorectal cancers is characterized by a distinct gene expression profile. J Pathol. 2008 Apr;214(5):594–602. doi: 10.1002/path.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah N, Sukumar S. The Hox genes and their roles in oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(5):361–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samuel S, Naora H. Homeobox gene expression in cancer: insights from developmental regulation and deregulation. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(16):2428–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanai M, Hamada J, Takada M, Asano T, Murakawa K, Takahashi Y, et al. Aberrant expressions of HOX genes in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(3):843–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freschi G, Taddei A, Bechi P, Faiella A, Gulisano M, Cillo C, et al. Expression of HOX homeobox genes in the adult human colonic mucosa (and colorectal cancer?) Int J Mol Med. 2005;16(4):581–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yahagi N, Kosaki R, Ito T, Mitsuhashi T, Shimada H, Tomita M, et al. Position-specific expression of Hox genes along the gastrointestinal tract. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2004;44(1):18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2003.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeda A, Goolsby C, Yaseen NR. NUP98-HOXA9 induces long-term proliferation and blocks differentiation of primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(13):6628–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.