Abstract

Stem cell therapies hold the great promise and interest for cardiac regeneration among scientists, clinicians and patients. However, advancement and distillation of a standard treatment regimen are not yet finalised. Into this breach step recent developments in the imaging biosciences. Thus far, these technical and protocol refinements have played a critical role not only in the evaluation of the recovery of cardiac function but also in providing important insights into the mechanism of action of stem cells. Molecular imaging, in its many forms, has rapidly become a necessary tool for the validation and optimisation of stem cell engrafting strategies in preclinical studies. These include a suite of radionuclide, magnetic resonance and optical imaging strategies to evaluate non-invasively the fate of transplanted cells. In this review, we highlight the state-of-the-art of the various imaging techniques for cardiac stem cell presenting the strengths and limitations of each approach, with a particular focus on clinical applicability.

Keywords: Cell tracking, Stem cells, Myocardial infarction, Heart failure, Molecular imaging

Introduction

In the last decade a great amount of research and clinical interest has been directed at stem cells (SC) for their potential to regenerate otherwise permanently damaged tissues. Work with these pluripotent cells has begun to be broadly explored, giving new hope for regenerative approaches in the therapy of myocardial infarction (MI).

Early success in preclinical studies demonstrated that stem cell-based therapy holds the potential to limit the functional degradation of cardiac function after MI [1]. This instigated clinical translation at a rapid pace (Table 1). Since the first study in 2002 which showed safety and effectiveness on intracoronary transplantation of autologous SC [2], several randomised, controlled clinical trials have been performed. Due to the absence of standardised protocols (cell number, timing and route of injection, baseline patient characteristics and techniques of evaluating cardiac function), results have been mixed. However, recent meta-analyses have shown that improvement in ejection fraction (EF), ventricular dimension and infarct area, despite being modest, are statistically significant [3–5].

Table 1.

Selected randomised clinical trials (>50 patients) of stem cell transplantation following myocardial infarction

| Study | Pts | Cell type | Assessment method | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REPAIR-AMI [101, 102] | 204 | Intracoronary BMC vs placebo | LV angiography | At 4 months LVEF increased in BMC vs placebo (mean±SD) increase, (5.5 ± 7.3% vs. 3.0 ± 6.5%; P = 0.01). At 12 months: death, recurrence of myocardial infarction, rehospitalization for heart failure significantly reduced. |

| ASTAMI [103, 104] | 100 | Intracoronary BMC vs control | 99mTc-SPECT; echo; MRI | No effect on global left ventricular function at 6 months and 3 years. |

| BOOST[105, 106] | 60 | Intracoronary BMC vs control | MRI | At 6 months global LVEF increase (6.7%). No effects at 18 months and 5 years. |

| Janssens et al. [107] | 67 | Intracoronary BMC vs placebo | MRI; [11C] acetate PET | At 4 months no effect on LVEF and LV volumes. Reduction of infarct volume (measured by serial contrast-enhanced MRI) was greater in BMC patients than in controls. |

| TOPCARE-AMI [16] | 59 | Intracoronary BMC vs CPC | LV angiography; MRI | At 4 months LV angiography showed significant increase of LVEF (50 ± 10% to 58 ± 10%), and significant decrease of end-systolic volumes (54 ± 19 ml to 44 ± 20 ml) without differences between the two cell groups. At 12 months MRI showed reduced infarct size and absence of reactive hypertrophy. |

| Meluzin et al. [108] | 60 | Intracoronary BMC (high and low doser) vs control | Echo; 99mTc-SPECT; 18F-FDG PET | LVEF improved in the group receiving the highest dose (108 cells) by 6%, 7%, and 7% at months 3, 6, and 12, respectively. |

| MAGIC [8] | 97 | SMB vs placebo injected in and around the scar | Echo | No improvement in regional or global LV function at 6 months. |

| Chen et al. [109] | 69 | Intracoronary BMSC (bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells) vs placebo | 18F-FDG; Echo | At 3 months LVEF significantly increased in the BMSC group (67 ± 11%) compared to controls (53 ± 8%) and the same group before implantation (49 ± 9%). No change in LVEF at 6 months versus 3 months. |

| Dill T et al. [110] | 204 | Intracoronary BMC vs placebo | MRI | In the BMC group, EF increased significantly by 3.2 ± 1.3 absolute percentage points at 4 months, and this increase was sustained at 12 months (+3.4 ± 1.3 absolute percentage points vs baseline). In the placebo group, EF was unchanged (+0.6 ± 1.2 absolute percentage points, at 12 months. |

BMC, bone marrow stem cells; CPC, circulating progenitor cells; SMB, skeletal myoblast. Pts, number of patients. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction

This field clearly benefited from the advancements in imaging sciences as almost all clinical trials involved the use of one or more imaging techniques to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of stem cell transplantion. Clinically established techniques allow for the evaluation of myocardial contractility, viability and perfusion, but do not provide the direct visualisation of transplanted stem cells, therefore their effective presence and viability can be only presumed. Ideally, transplanted cells in the infarcted myocardium are expected to survive engraftment, be self-renewing and differentiate into cardiac cells (cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells or smooth muscle cells) forming electromechanical junctions with adjacent viable tissues. However, the long-term improvement appears to be most closely related to paracrine effects rather than transdifferentiation of the cell transplant and heart muscle regeneration [6].

Great strides in imaging techniques and technologies have been made that enable the cellular and molecular imaging of transplanted stem cells, their short and long term fate and in some instances their viability and differentiation status.

Stem cells for cardiac repair

Currently adult stem cells, embryonic stem cells (ESC) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) can be used to regenerate heart tissue. Adult stem cells comprise skeletal myoblasts (SM), mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), bone marrow- derived stem cells (BMC), endothelial (EPC) and cardiac progenitor (CPC) cells. SM were the first option to be used in stem cell transplant as they are available from an autologous source (therefore lacking ethical or immunogenicity issues), and have been demonstrated to provide functional benefit after myocardial infarction in animals [7]. However, in a recent clinical trial no sustained benefit in the global EF was observed and increased number of early postoperative arrhythmic events was reported [8].

BMC transplantation has been shown to improve heart function in animal models [1, 9]. However, others have identified that most of the cells injected adopted a mature haematopoietic transformation and only a small number of cardiomyocytes expressed the genetic markers of the transplanted cells [10, 11]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) constitute the stromal compartment of bone marrow and, importantly, are not hematopoietic. These are able to differentiate into a variety of cell types [12] and improvement in whole heart function has been described in a swine model of myocardial infarction [13]. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue have been shown to contain vascular/adipocyte progenitor cells and adult multipotent mesenchymal cells (adipose tissue-derived stromal cells [14]). ASC have been reported to improve left ventricular function in animal models of myocardial infarction [15]. The circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) represent a more accessible source of autologous SC and have been used in clinical trials [16]. The existence of a subpopulation of resident cardiac SC (RCSC) has been reported that is self-renewing, clonogenic and multipotent, capable of differentiating in myocytes, smooth muscle and endothelial cells [17]. Promising results have been reported in preclinical studies [18], and results of phase I clinical trials, started in 2009, are awaited with interest.

To date, ESC-derived cardiomyocytes [19] and ESC-derived endothelial cells [20] have been successfully used to treat heart disease in animal models. However several problems are related to their use, including immunological incompatibility with the host [21], the tendency to form teratomas [22] and ethical controversies. Several studies have been performed to manipulate the expression of transcription factors with the goal of transforming somatic cells (derived from an autologous source, such as keratinocytes and fat stromal cells) into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) [23]. These cells possess the same advantages as ESC, without the associated immunological and ethical complications. Cardiomyocytes have been successfully obtained from iPS in vitro [24] and their transplantation in animal models of infarction resulted in improved myocardial function [25].

To summarise, ESC and iPS have the greater potential for cardiomyogenesis, while the formation of new cardiomyocytes by transdifferentiation of SM and BMC has so far not been supported with convincing evidence. It should be noted that several studies have reported moderate improvements in whole cardiac function after transplantation of SM and BMC [7, 26]. It has been demonstrated that SCs are responsible for paracrine effects, consisting of the release of various cytokines or growth factors (eg. VEGF, bFGF) that increase collateral perfusion and neoangiogenesis and influence the contractile characteristics of chronically failing myocardium [26].

Imaging of stem cells

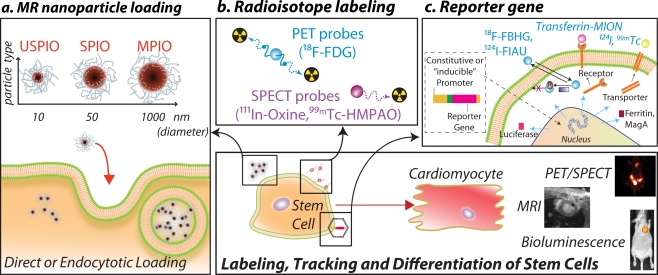

The ability to image and monitor the biodistribution, viability and possibly the differentiation status of implanted SCs is of massive clinical and research benefit. All of the pre-clinical and clinical imaging techniques have been leveraged towards this goal; each providing unique advantages and limitations. Figure 1 illustrates the major paradigms for the labelling of SC for detection by the various imaging approaches. Table 2 reports the most important preclinical studies in the field. Table 3 summarises the most relevant features of each imaging technique.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the current technologies available for stem cell (SC) tracking. Before implantation SC can be passively loaded with: a superparamagnetic nanoparticles that allow for the MR detection of labelled cells as areas of signal loss; b radiolabelled PET or SPECT probes. c Reporter gene approaches consist of the introduction through viral or non-viral-vectors of a reporter gene driven by a constitutive or inducible promoter. The reporter gene undergoes transcription to mRNA, which is translated into a protein that can be: 1) an enzyme (as HSV1-tk or luciferase), 2) a receptor (as transferrin receptor or hSSTR [human somatostatin receptor]) 3) a transporter (hNIS [human sodium iodide symporter]) 4) intracellular iron storage protein (ferritin). When a complementary reporter probe is administered, it concentrates or activates only at the site where the reporter gene is expressed. The level of probe accumulation is proportional to the level of reporter gene expression and can be monitored to evaluate the number of cells or the induction of a specific reporter gene

Table 2.

Selected cell tracking studies of SC

| Study | Species | Cell type | Detection method | Delivery | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | |||||

| Kraitchman et al. [111] | swine | MSC | SPIO | Intramyocardial -percutaneous | Detection of tranplanted cells (25.8%) up to 3 weeks. |

| Amado et al. [112] | swine | MSC | SPIO | Intramyocardial- percutaneous | Gradual loss of intensity of the SPIO label but retection of tranplanted cells (42.4%±15) at 8 weeks. |

| Stuckey et al. [113] | rat | BMC | GFP-SPIO | Intramyocardial –direct | No improvement in LEVF. Detection of tranplanted cells up to 16 weeks confirmed by MR and immunofluorescence. |

| Amsalem et al. [43] | rat | MSC | SPIO | Intramyocardial –direct | At 4 weeks after injection, most of the transplanted labelled MSCs did not survive and their iron content was engulfed by resident macrophages. Injection of labelled or unlabelled cells attenuate ventricular dilatation and dysfunction after MI. |

| Ebert et al. [114] | mice | mESC | SPIO | Intramyocardial -direct | Detection up to 4 weeks by MRI. LVEF identical between the tranplanted group and control. |

| Terrovitis et al. [45] | rat | hCDCrCDC | SPIO | Intramyocardial -direct | Signal void persisted after 3 weeks in both syngeneic and xenogeneic cell implantation. Immunohistochemistry identifies the iron containing cells as macrophages. |

| Radionuclide | |||||

| Chin et al. [62] | swine | MSC | 111In-oxine | Intravenous | Significant lung activity that obscured the assessment of myocardial cell tracking. |

| Brenner et al.[63] | rat | HPC-CD34+ | 111In-oxine | Intracavitary (left ventriculum) | Impairment of cell proliferation and differentiation induced by 111In-oxine. At 96 h only 1% of radioactivity was detected in the heart. |

| Blackwood [65] | dog | BMC | 111In-tropolone | Intramyocardial -direct | Viability at day 6 after intramyocardial injection was calculated to be 75%. |

| Terrovitis et a.. [82] | rat | rCDC | 18F-FDG | Intramyocardial -direct | Different retention values were observed at 1 h after injection of cells with normal condition (17.8%±7.3), arrested heart (75.8%±18.3), adenosine injection (35.4%±5.3) and adenosine plus fibrin glue (39.3%±11.6). |

| Mitchell et al. [66] | dog | EPC | 111In-tropolone | Intramyocardial -percutaneous | 15 days after intramyocardial injection SPECT/CT imaging demonstrated comparable degrees of retention: 57%±15 for the subepicardial injections and 54%±26 for the subendocardial injections. |

| Multimodal | |||||

| Terrovitis et al.. | rat | rCDC | 99mTc, 124I; hNIS | Intramyocardial -direct | Detection up to 6 days after injection and their presence validated by ex vivo imaging and qPCR. |

| Qiao et al. [98] | rat | mESC | SPIO; HSV1-tk+ 18F-FHBG | Intramyocardial -direct | Increasing 18 F -FHBG uptake up to 4 weeks. Most of the SPIO were contained in infiltrating macrophages at week 4. Teratoma formation. Increased LVEF. Only <0.5% of the implanted cell were cardiomyocytes. |

| Chapon et al. [115] | rat | rBMC | SPIO; 18F-FDG | Intramyocardial -direct | MRI detection of SPIO labelled cells grafted in the heart up to 6 weeks, confirmed by hystology. At 1 week increased 18 F-FDG uptake in BMC implanted heart vs control. No improvement of heart function. |

| Higuchi et al. [99] | rat | hEPC | SPIO; NIS +124I | Intramyocardial -direct | Rapid decrease of 124I uptake after day 3. Signal not detectable at day 7. MRI signal void remained unchanged throughout the follow-up period. Histology confirmed the presence of transplanted cells on day 1 but not on day 7, when iron was contained only in resident macrophages. |

| Li et al. [116] | rat | RCSC | Fluc + D-Luciferin; 18F-FDG PET; echocardiography; MRI | Intramyocardial -direct | Implanted cells detected up to 7 weeks by bioluminescence. No improvement in cardiac function assessed by 18F-FDG PET, MRI, echocardiogram and invasive hemodynamic pressure volume-analysis. |

BMC (bone marrow derived Stem Cells); MSC mesenchymal stem cells; mESC (mouse embryonic stem cells); hCDC (human cardiac derived stem cells), rCDC (rat cardiac derived stem cells); HPC (hematopoietic progenitor cells); hEPC, human Endothelial Progenitor Cells; RCSC (resident cardiac stem cells); NIS (sodium iodide symporter); Fluc (firefly luciferase); hNIS (human sodium-iodide symporter; MI, Myocardial infarction

Table 3.

What to image and how to image

| Imaging modality | Spatial resolution (mm) | Sensitivity (mol/L) | Cell Manipulation | What to image | How to image | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Imaging | FRI: 2–3 mm; FMT: 1 mm | 10−9–10−12 | Cells labeled with near-infrared probes (fluorochromes, Quantum dots, etc.) | Residence, homing, quantification (FMT) | Direct imaging; at NIR wavelenghts can image deep tissue | Multiplexed imaging | Not suitable for clinical translation; relatively low spatial resolution |

| Bioluminescence Imaging | 3–5 | 10−15–10−17 | Cells transduced to express luciferase | Residence, homing, viability, differentiation, quantification | After systemic injection of D-Luciferine or Coelenterazine | Easy, high sensitivity, high-throughput, low cost; assessment of cell viability | Not suitable for clinical translation; surface imaging; relatively low spatial resolution; requires completely dark environment |

| PET | 1-2 (μPET); 6–10 (clinical PET) | 10−11–10−12 | Cells loaded with 18F-FDG; 64Cu labelled compounds | Residence, homing, quantification | Direct imaging | High sensitivity, translational | Radiation; only short term cell tracking |

| Cells transduced to express PET reporter genes (HSV1tk, HSV1-sr39tk ) | Residence, homing, differentiation, quantification, | After systemic injection of correspondent radiolabelled probe (18F-FHBG, 18F-FEAU, etc.) | High sensitivity, long term cell tracking; assessment viability | Radiation; need to transduce cells; potential immunogenicity | |||

| SPECT | 0.5-2 (μSPECT); 7–15 (clinical SPECT) | 10−10–10−11 | Cells labelled with 99mTc-, 111In-labelled compounds | Residence, homing, quantification | Direct imaging | High sensitivity, translational; assessment viability | Radiation; only short term cell tracking |

| Cells transduced to express reporter genes (hNIS ) | Residence, homing, viability, differentiation, quantification, | After systemic injection of correspondent radiolabeled probe ( 99mTc, etc.) | High sensitivity, long term cell tracking | Radiation; need to transduce cells; potential immunogenicity | |||

| MRI | 0.01–0.1 (small animal); 0.5–1.5 (clinical) | 10−3–10−5 | Cells labeled with Iron Oxides; Gd or Mn chelates; perfluorocarbon (19F) | Residence, homing, migration, quantification | Direct imaging | High spatial resolution; high soft tissue contrast; functional imaging | Relatively low sensitivity; long scanning times; probe dilution upon cell proliferation; persistence of SPIO after cell death (macrophage) |

| Cells transduced to express MRI reporter genes β-galactosidase, transferrin receptor, ferritin, MagA and lysine-rich proteins | Residence, homing, quantification, migration, differentiation | Direct imaging or after injection of iron oxides (transferrin receptor, ferritin) | High spatial resolution; high soft tissue contrast; functional imaging; no probe dilution; | Low sensitivity; need to transduce cells; potential immunogenicity |

NIR, Near-Infra red imaging; FRI, Fluorescence reflectance imaiging; FMT, Fluorescence molecular tomography

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a widely established technique for the evaluation of cardiac anatomy and function, often through the addition of paramagnetic contrast material [27]. Taking advantage of its excellent spatial (10–100 μm [small animal MRI]); 500–1500 μm [clinical]) and temporal resolution SC labelled with superparamagnetic and paramagnetic agents can be visualised [28, 29]. Multispectral non-1H MR imaging (specifically 19F) has also been exploited to enable tracking of transplanted cells.

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles

Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles provide labelled cells with a large magnetic moment and are detectable by MR imaging devices or benchtop relaxometers. SPIO functions by acting as magnetic inhomogeneities, locally disturbing the magnetic field. This leads to enhanced dephasing of protons, resulting in decreased signal intensity on T2-weighted and T2*-weighted images (Figs. 2 and 3). These nanoparticles often consist of a core of iron oxide (magnetite and/or maghemite) with a polymeric or polysaccharide coating. They are widely viewed to be biocompatible, have a limited effect on cell function and can be synthesized to be biodegradable. According to their size (diameter), these are classified as ultrasmall paramagnetic iron oxide (USPIO, <10 nm), monocrystalline iron oxide particles (MION, or cross-linked CLIO; 10–30 nm), standard superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO; 60–150 nm) and micron-sized iron oxide particles (MPIO, 0.7–1.6 μm). Of note, ferucarbotran (Resovist®; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) and ferumoxides (Feridex I.V.®, Advanced Magnetic Industries, Cambridge, Maryland, USA; Endorem®, Guerbet, Gorinchem, the Netherlands) have been approved by the FDA for contrast enhanced-MRI imaging of liver tumors [30] and metastatic involvement of lymph nodes [31].

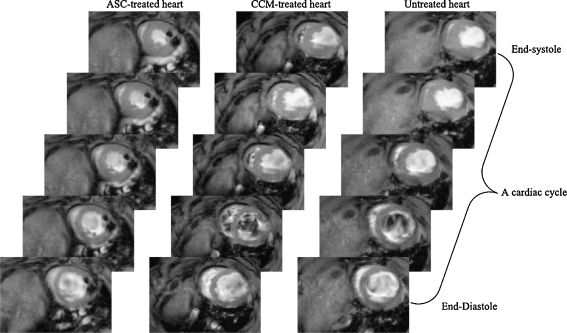

Fig. 2.

Anatomical and functional MR evaluation after transplantion of adipose-derived stem cell (ASC) and relative controls: cell culture medium (CCM), and untreated hearts. The CCM-treated and untreated hearts showed evident thinning in the anterior wall of the left ventricle. From Wang, L. et al. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1020-H1031 2009 [15] (with permission)

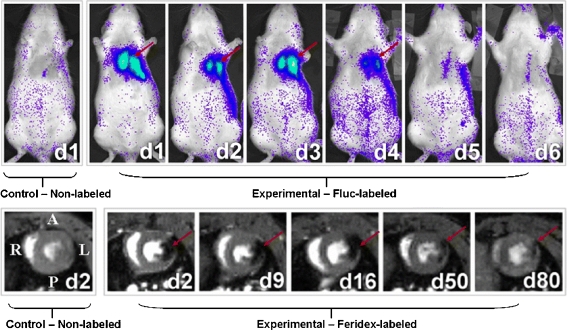

Fig. 3.

Longitudinal BLI and MRI of H9c2 cells after transplantation. BLI shows a robust distinct heart signal on day 1 (red arrow), compared to no discernable signal in a representative control rat having received non-labelled cells (top panel, left). The signal increases slightly on day 3 but decreases rapidly to near background levels by day 6. MRI imaging of a representative rat injected with the same amount of cells labelled with Feridex shows a large hypointense signal (red arrow) in the anterolateral wall of the myocardium. The size of the signal decreases slightly over time, and the signal persists for at least 80 days post cell injection. No signal is observed in control rat that received non-labelled cells (bottom panel, left) Chen, I. Y et al. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009 May-Jun;11:178–87. [42] (with permission)

Cell uptake is mediated through the size and electrostatic charge conditions of the SPIO [32], schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a. Further, loading can be augmented through the addition of cell penetrating peptides, electroporation or transfection agents [33].

Studies reported that SPIOs do not affect cell viability, proliferation, differentiation or migration [34–38]. However, recent work has raised several concerns, such as decreased MSC migration and colony-formation ability [39], and interference with cell function [40, 41]. A major issue beyond potential cellular effects is the question of contrast specificity to the presence of cells. Namely, the hypointense signal is maintained at a site regardless of cell viability and SPIO are present not necessarily within implanted SC at longer time points [42], but rather in phagocytosing monocytes following SC death [43]. Recently, Winter et al. reported the absence of any discrimination between healthy successfully engrafted SC and dead SC phagocytosed by macrophages within the heart. In particular, no differences in signal voids up to more than 40 days were observed with dead and viable cells recipient with respect to size, number and localisation [44]. Similarly, it has been demonstrated that MRI overestimates the SPIO labelled SC survival after transplantation in the heart [45]. Furthermore, SPIO-induced hypointensity can sometimes be difficult to interpret because it may be obscured by the presence of endogenous blood derivates, such as hemosiderin [46]. The clinical translation of SPIO for cell tracking is further reduced now that ferumoxides (Feridex® or Endorem®) are no longer available in the USA and Europe. However, the use of iron oxides approaches should not be discouraged as they provide very high sensitivities. New compounds with improved tissue clearance properties (therefore higher specificities) are awaited from material sciences research.

Paramagnetic ions

Cell labelling with “positive contrast” such as gadolinium (Gd) chelates and manganese (Mn) chloride compounds allow the visualisation of SC as hyperintense signal on T1-weighted images. Internalization of Gd can be accomplished by exposure of cells to Gd chelates or through the use of liposomal formulations [33]. MRI sensitivity in the detection of Gd-labelled cells is lower compared to SPIO-labelled cells and is dependent upon contrast behaviour and relaxivity in the cellular compartment (endosomes) in which they are localised [47, 48]. This is a result of the reduced water accessibility to chelated ions following intracellular concentration, resulting in decreased relaxivity. To overcome these issues several approaches have been considered to drive the endosomal escape of paramagnetic compounds [49]. Furthermore, safety issues might be related to the rapid dechelation of compounds at the low pH of lysosomes and endosomes raising concerns related to free Gd3+ ions [50].

Sub-millimolar concentrations of Mn chloride (MnCl2) have been sufficient to enable SC labelling and detection for both in vitro and in vivo MR, with no detectable toxicity. Also in the same study the potential of MnCl2 labelling in the assessment of SC viability by T1 and T2 mapping was investigated in in vitro studies [51]. Mn-oxide nanoparticles have recently been used to label and track implanted glioma cells. Of considerable interest, the feasibility of successfully tracking two cell populations simultaneously has been suggested, where one is labelled with Mn-Oxide and the other with SPIOs [52]. These and other paramagnetic ion techniques offer the hope that positive contrast approaches will enable sensitive MR tracking of SC in vivo. Novel nanotechnology approaches are becoming available for stem cell tracking such as gadolinium-containing carbon nanocapsules (Gadonanotubes), whose T1 relaxivity is greater than that of any known material to date (outperforming clinically available Gd-based contrast agents by 40-fold) [53]. They will definitely play a role in the future of imaging sciences as soon as their toxicity profiles, currently under investigation, have been clarified.

19F MR

Similar to the imaging of relaxation of 1H from water, 19F can be used as the basis of the signal for MR spectroscopy and image formation. While this technique is not implemented widely in the clinic, there are unique advantages to fluorine-MR that make it an attractive option for SC tracking in myocardial applications. 19F is not present naturally in soft tissues therefore its signal is exclusively derived from the exogenous contrast agent applied, be it a perfluorocarbon particle or fluorinated nucleosides [54]. 19F MRI can be used with existing 1H imaging hardware since 19F and 1H gyromagnetic ratios differ by only 6%.

Importantly, 19F signal can be overlaid on 1H-MR anatomical images for a highly selective, high-resolution map of cell transplantation. This technique allows for quantitative determination of the cell population [55]. A perfluorocarbon particle loaded cell scheme has been used to show the unequivocal and unique signature for SC, enabling spatial cell localization via19F- MRI and quantitation via 19F-spectroscopy [56]. Perfluorocarbons have been extensively studied and used as blood substitutes, therefore their toxicity profiles are known. 19F cell tracking has attracted interest, but is still at an early stage of development. It should be noted that this method does suffer from the drawback of lower sensitivity requiring longer imaging times. Efforts are underway to address these deficits including imaging hardware, imaging sequences, and label improvement and 19F MR imaging is expected to play a role in cell tracking in the future [54].

Radionuclide imaging

Imaging of SC has also taken advantage of the high sensitivity (10-10−10−12 mol/L vs 10−3–10−5 mol/L of MRI) and quantitative (acute cell retention as a percentage of the net injected dose per weight, [%ID/g]) characteristics of radionuclide imaging [57]. However, PET and particularly SPECT have inferior spatial resolution (1–2 mm) compared with MRI. Moreover, radionuclide-labelled cells can only be visualised as long as the radioactivity is still detectable (e.g. 18F: 110 min; 111In: 2.8 days; 99mTc: 6 h). This sets an appreciable limitation on the radioisotopes direct labelling value for medium- and long-term SC transplant monitoring. SPECT has been largely used to investigate the short-term fate of transplanted cells labelled with radioactive compounds such as 111In-oxine [58–63], 99mTc-hexamethylprophylene amine oxine (HMPAO) [64] or 111In-tropolone [65, 66]. A persistent limitation for deployment of SPECT is that in order to generate useful (quantitative) images within a reasonable time frame, the administration of relatively large doses of radioactivity are required. This poses the concern of inherent radiation damage (reduced viability and proliferation). In the case of 111In, Auger electrons are also emitted leading to adverse biological effects in very short distances (from the nm to μm range). Brenner et al., demonstrated that despite the homing of progenitor cells into the infarction area, cell labelling with 111In-oxine impairs significantly the viability, proliferation and differentiation at 48 h after implantation [63]. Similar results were observed after exposure of murine haematopoietic progenitor cells at even much lower levels of radioactivity [67]. The use of other compounds, such as 111In-tropolone, inhibited cell proliferation 3 days after labeling [68]. To abrogate these effects, it has been suggested that only a fraction of the SC population be labelled [69]. Regardless of the method used, very few studies have reported the absence of any cell function impairment [58, 62]. These studies underline the need for further in vitro studies considering different SC, exposed to different activities and importantly following the same labelling protocol.

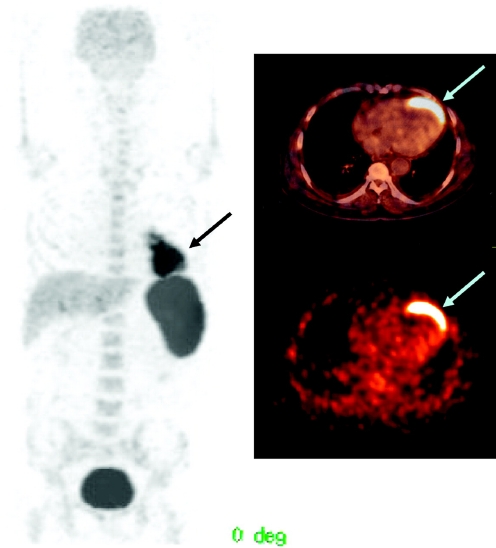

Positron emission tomography (PET) has been regarded as having higher sensitivity (2 to 3 orders of magnitude) and better spatial and temporal resolution than SPECT [70]. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) has been used for cell labelling and short term imaging in preclinical [71] and clinical settings (Fig. 4) [72, 73]. After intracoronary injection all stem cells showed poor engraftment regardless of cell type and number of implanted cells [61, 72, 73]. In all cases intravenous injection of SC did not show detectable homing of cells to the myocardium [72, 73].

Fig. 4.

PET/CT images of a patient with hystory of anterior wall infarction. After percutaneous intervention 18 F-FDG labelled cells were implanted via intracoronary catheter and images obtained at 2 hrs after the procedure. Total amount of SC at the injection site was measured (2.1% of injected dose). From Kang et al. J Nucl Med 2006; 47:1295–1301. [73] (with permission)

Augmenting the higher sensitivity, the wider availability of hybrid PET-CT systems allows for a combination of anatomical non-invasive coronary angiography and cell tracking. This multimodal imaging capability and clinical availability are tempered somewhat by the the short half life of 18F. Isotopes with longer half life, such as 64Cu (12.7 h) have been suggested [74]. However, with radionuclide based techniques pursued so far, only the immediate fate of transplanted stem cells can be interrogated.

Reporter genes

Reporter gene approaches have significant potential to reveal insights into the mechanisms and fate of SC therapies. The reporter gene paradigm requires often the appropriate combination of reporter transgene and a reporter probe, such that the reporter gene product has to interact with an imaging probe (optical, nuclear, magnetic) and when this event occurs the signal may be detected and quantified with the corresponding imaging technique (Fig. 1c).

Several advantages of reporter gene approaches have been described [75]. Namely, this system identifies with exquisite specificity only viable cells (which actively contain the gene product) and allows long term tracking of transduced SC (circumventing issues of probe dilution with cellular proliferation). Reporter genes can be designed as “constitutive” whose signal is “always turned on” (suitable for the evaluation of transplantation, migration and proliferation of stably transduced SC) or “inducible” reporter gene which is activated and regulated by specific endogenous transcription factors and promoters [75, 76] providing a non-invasive readout of information regarding SC differentiation.

The most widely used reporter gene for radiotracer based imaging is HSV1-tk (Herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase) and its mutant, the HSV1-sr39tk. Unlike mammalian TK1, this enzyme efficiently phosphorylates purine and pyrimidine analogues which results in trapping and accumulation of these ligands. It has been successfully used in association with 18F or 124I -2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-5-iodo-1-[β]-D-arabinofuranosyluracil (18F-FIAU and 124I-FIAU), 18F 2′-fluoro-5-ethyl-1-[β]-D-arabinofuranosyluracil (18F-FEAU), and 9-(4-[18F]fluoro-3-hydroxymethylbutyl)guanine (18F-FHBG) [75, 77].

Wu et al., pioneered the reporter gene approach in the heart by imaging in vivo transplanted cells (expressing luciferase or HSV1-sr39tk) up to 2 weeks by 18F-FHBG PET imaging or BLI [78]. Furthermore, Cao et al., reported survival and proliferation (through increasing signal up to 4 weeks) of murine ES stably transduced with a triple fusion reporter gene, enabling simultaneous PET, bioluminescence and fluorescence imaging [79].

Despite the advantage of signal amplification (through probe phosphorylation and accumulation within cells) of HSV-tk based approaches, its immunogenicity might limit use in humans [80]. To overcome this limitation, the human mitochondrial thymidine kinase type 2 (hTK2) have been proposed [81]. An alternative is the sodium iodide symporter [51] as a PET and SPECT reporter gene used in conjunction with 124I or 99mTc (pertechnetate), respectively [75, 82]. Here, despite the lack of probe/signal amplification observed in receptor- and transporter-based techniques (as 124I or 99mTc are free to diffuse out of the cells), hNIS is not immunogenic (since it is expressed in the thyroid, stomach salivary gland, choroid plexus but not in the heart) and does not require complex radiosynthesis of the probes. Nevertheless, in reporter gene approach for the imaging of SC-based cardiac therapy several important issues remain. First, the non-physiological expression of reporter gene proteins may perturb the critical SC cellular and therapeutic functions. To be fully reliable, this system has to guarantee the long term expression of the reporter gene in the proliferating population. Adenoviral transfection is hampered by episomal gene expression (the reporter gene is not integrated in the chromatin, and because they are not replicating, they become diluted with cell proliferation) and by immunogenicity (leakiness of immunogenic adenoviral proteins that can lead to an immune response) [83]. On the other hand, lentiviral vectors accomplish the integration of the reporter gene in the host cell chromatin allowing stable expression in dividing cells [84] and circumventing immunogenicity [85]. Even when lentiviral vectors are used however, transgene expression can be silenced by DNA methylation especially when strong promoters, such as CMV, are used to drive the expression of the reporter gene [86]. The integration of the reporter gene within the genome has raised concerns about the risk of mutagenesis and potential oncogenicity [87].

The imaging of differentiation in vivo was recently investigated by Kammili et al., by employing a novel dual-reporter mouse embryonic SC line. Here, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) was used as a “constitutive reporter”, and the firefly luciferase reporter as an “inducible reporter”. This latter gene was under the control of the cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger 1 (Ncx1) promoter which showed increased activity upon differentiation of SC into beating cardiomyocytes [76].

Several candidates have been proposed as MRI reporter genes such as β-galactosidase, transferrin receptor, ferritin, MagA and lysine-rich proteins [88, 89]. Recently, SM engineered to express ferritin have been transplanted in infarcted heart and detected (as decreased signal up to 25%) up to 3 weeks [90]. Several studies have been reported with the application of MR reporters, however, none of these strategies have led to a significant number of follow-up studies. This is due to the low sensitivity of MRI for imaging of gene activity in vivo.

Optical imaging

BLI

In contrast to the immediate clinical impact of magnetic and nuclear tomographic imaging, optical imaging techniques such as bioluminescence, planar and fluorescence-mediated tomography have been largely restricted to use in preclinical models. Bioluminescence imaging is commonly used for cell tracking in SC transplantation studies [78, 79, 91] (Figs. 3 and 5). SC are transduced with a luciferase gene and implanted in the recipient animal. Following injection, the probe (D-Luciferin) is oxidized only in the cells expressing luciferase in presence of ATP, O2 and Mg2+ resulting in light photons being emitted (which can be detected by ultrasensitive charge-coupled device [CCD] cameras). BLI has many advantages: it is highly sensitive, quantitative, simple and inexpensive. However, the barrier to clinical translation lies in the inherent limitations imposed by poor tissue penetration (1–2 cm) (allowing only surface imaging), high rates of scattering of visible wavelength photons on the human scale and low resolution (3–5 mm) (which hamper the exact evaluation of the exact location of the cells) [57].

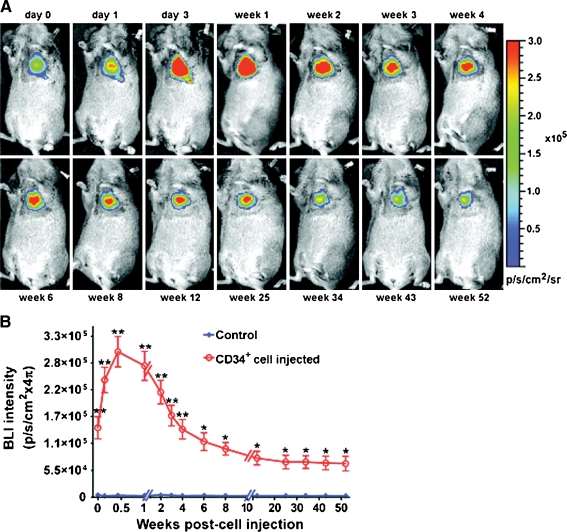

Fig. 5.

Bioluminescence imaging of CD34+ cells expressing the TGL gene (HSV1-tk, e-GFP, f-luc) and implanted in the heart of a SCID mouse. Systemically administered luciferin is activated (oxidized by luciferase) in the injected cells. Here we see follow-up of implanted cells up to 52 weeks post-implantation. Measurement of emitted light in CD34+ implants is higher than in controls (PBS injection). From Wang, J. et al. Circ Res 2010;106:1904–1911. [91] (with permission)

Fluorescence

Direct labelling of SC with fluorescent probes for visualisation in vitro and in vivo has been fueled by the availability of near infrared (NIR) probes, as their spectral properties are matched to lower tissue attenuation in the so-called NIR-window. This provides greater signal penetration of tissue through reduced light absorption and tissue scattering. Therefore they have clinical potential, however limited to near-surface or intraoperative imaging stem cell tracking.

Near infrared imaging provides high sensitivity as well as tomographic capabilities and there is no evidence at present that dyes released after cell death are taken up by macrophages. Intracoronary delivery of MSC labelled with the NIR dye IR-786 has been successfully tracked in a swine model of myocardial infarction and sensitivity of 10.000 cells has been reported [92].

Quantum dots (QD) are a class of inorganic, fluorescent nanoparticles that have been successfully used to label SC. Biocompatibility of QD at low concentrations has been demonstrated in vitro in MSC cultures [93] and the absence of adverse effects on cell viability, proliferation or differentiation reported [94]. One of the most attractive qualities of these nanoparticles is their capacity for multiplexed imaging. The tracking of different cell populations is concurrently achieved by labelling cells with different QDs. Multiplex optical imaging of QD-labelled embryonic stem cells have been reported up to 14 days from injection in mice [94]. Moreover, it has been shown that single QD-MSC can be detected in histological sections for at least 8 weeks after delivery [95]. The long-term effects on SC functionality are still unknown, however concerns are related to their metallic core include its exposure or dissolution which may result in toxicity, particularly from heavy metals such as Pb, Cd and Se [96, 97]

Multimodal imaging

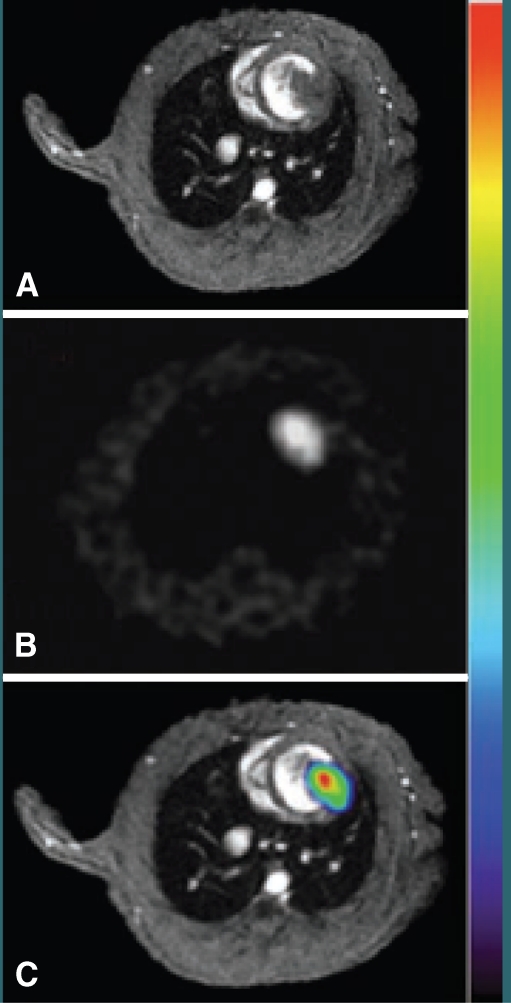

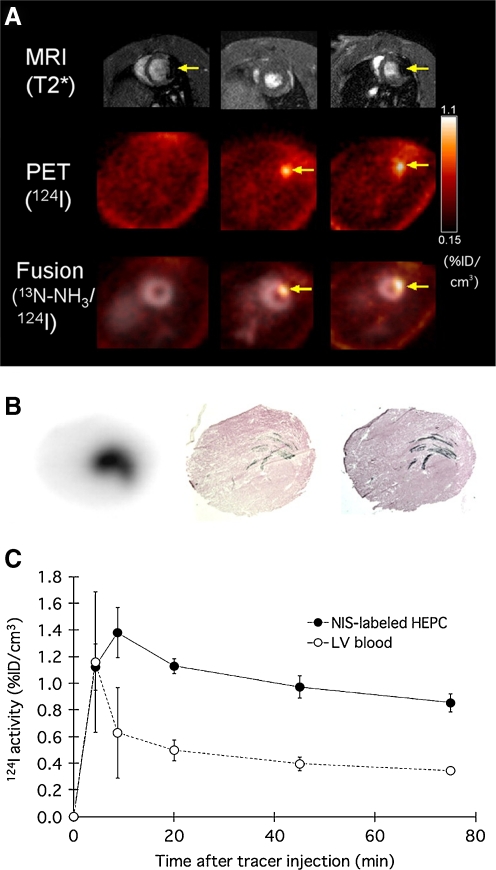

The possibility of complementing the sensitivity of radionuclide or optical techniques with the high-resolution anatomical information from MRI is a key player in the clinical and research future of SC tracking. To date, the most interesting approach has been to develop transgenic cells that carry an optical/nuclear imaging reporter together with passive labelling with MRI contrast agents before administration. Qiao et al. assessed the survival and proliferation of SPIO-labelled murine ESC transduced with HSV1-sr39tk longitudinally (4 weeks) following injection into the healthy or infarcted myocardium. ESCs grafted and underwent proliferation, as shown by increasing uptake of 18F-FHBG in PET (Fig. 6) and decreasing the size of MR hypointense areas due to SPIO dilution. Interestingly at week 4 the majority of SPIO labels (released upon cell death) were phagocytized and contained in infiltrating macrophages rather than the ESC. Despite teratoma formation, a slight increase in left ventricular ejection fraction in ESC-treated animals was observed, mainly as a result of paracrine effects, as cardiac differentiation of implanted ESC was less than 0.5% [98]. In a similar study human EPC derived from CD34+ mononuclear cells of umbilical cord blood were transduced with NIS reporter gene and labelled with SPIOs. Rapid loss of viable grafted cells was observed, as 124I PET accumulation decreased below detection limit at 3 days after transplant. However, MRI signal void resulting from SPIO persisted, corresponding to retention of SPIOs within macrophages after graft cells’ death (Fig. 7) [99]. Triple fusion reporter gene have been widely applied for multimodality fluorescence, bioluminescence and nuclear imaging approaches [100]. Recently, in a quad-modal optical, PET, CT and MRI coregistration approach CD34+ cells were transduced with a triple fusion reporter gene (e-GFP, f-Luc and HSV1-tk). Bioluminescence imaging revealed that cells persisted in the heart up to 12 months and MRI studies reported improvement in the left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved up to 6 months (Fig. 5) [91].

Fig. 6.

Co-registration of MRI a and 18 F-FHBG PET b of murine ESC transduced with HSV1-sr39tk and passively labelled with SPIO. Images depict the presence and tracking of SC 14 days after transplantation. This hybrid imaging c approach leverages the advantages of each technique; the fine anatomical resolution of MR and the specificity of nuclear imaging. From Qiao et al. Radiology 250:3, 821–829. [98] (with permission)

Fig. 7.

a MRI (upper row), 124I-PET (middle row), and fusion images 13 N-NH3 (gray scale)/ 124I (colour scale) (bottom row) of rat heart 1 day after injection of EPC labelled with iron (left), NIS only (middle), or both iron and NIS (right). Signal void of iron-labeled HEPCs is observed by MRI whereas HEPCs expressing NIS showed focal 124I accumulation by PET. b Consecutive myocardial sections showing the presence of transplanted cells: autoradiography for 124I uptake mediated by NIS reporter (left), X-galactosidase staining for LacZ gene expression of graft cells (middle), and Prussian blue staining for iron particle detection (right). c Mean±SD time–activity curves after 124I administration of transplanted cell and left ventricular blood measured by PET. From Higuchi T et al. J Nucl Med, 50:1088–1094. [99] (with permission)

Conclusion

Many of the approaches to image stem cells are promising but further work is required before a wide clinical translation becomes reality. Beyond the unresolved safety and ethical issues, crucial questions: “What is the best route for cell delivery ?” “What kind and how many cells ?” and “When to inject ?” remain.

It has become clear that there is no single ‘best method’ in cell tracking. Rather there is an array of high sensitivity, high spatial resolution and functional techniques that work best in combination. The persistent trends in molecular imaging are: to focus on the development of novel MR-compatible probes able to monitor and track with sufficient sensitivity and specificity the fate of transplanted cells, new PET/SPECT reporter genes with lessened immunogenicity and oncogenicity issues, and the application of related radioprobes with better pharmacokinetic profiles.

Acknowledgements

This article has been supported in part by the ENCITE (funded by the European Community under the 7th Framework program) and by the NIH R25T CA096945.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, et al. Repair of infarcted myocardium by autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:1913–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034046.87607.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Latif A, Bolli R, Tleyjeh IM, et al. Adult bone marrow-derived cells for cardiac repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipinski MJ, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Abbate A, et al. Impact of intracoronary cell therapy on left ventricular function in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: a collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-Rendon E, Brunskill SJ, Hyde CJ, Stanworth SJ, Mathur A, Watt SM. Autologous bone marrow stem cells to treat acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1807–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korf-Klingebiel M, Kempf T, Sauer T, et al. Bone marrow cells are a rich source of growth factors and cytokines: implications for cell therapy trials after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2851–2858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DA, Atkins BZ, Hungspreugs P, et al. Regenerating functional myocardium: improved performance after skeletal myoblast transplantation. Nat Med. 1998;4:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menasche P, Alfieri O, Janssens S, et al. The Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation. 2008;117:1189–1200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon YS, Wecker A, Heyd L, et al. Clonally expanded novel multipotent stem cells from human bone marrow regenerate myocardium after myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:326–338. doi: 10.1172/JCI22326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428:668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004;428:664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari G, Cusella-De Angelis G, Coletta M, et al. Muscle regeneration by bone marrow-derived myogenic progenitors. Science. 1998;279:1528–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quevedo HC, Hatzistergos KE, Oskouei BN, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells restore cardiac function in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy via trilineage differentiating capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14022–14027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903201106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polascik TJ, Manyak MJ, Haseman MK, et al. Comparison of clinical staging algorithms and 111indium-capromab pendetide immunoscintigraphy in the prediction of lymph node involvement in high risk prostate carcinoma patients. Cancer. 1999;85:1586–1592. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990401)85:7<1586::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Deng J, Tian W, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells are an effective cell candidate for treatment of heart failure: an MR imaging study of rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1020–H1031. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01082.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schachinger V, Assmus B, Britten MB, et al. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction: final one-year results of the TOPCARE-AMI Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114:763–776. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawn B, Stein AB, Urbanek K, et al. Cardiac stem cells delivered intravascularly traverse the vessel barrier, regenerate infarcted myocardium, and improve cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3766–3771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405957102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Wu JC, Sheikh AY, et al. Differentiation, survival, and function of embryonic stem cell derived endothelial cells for ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2007;116(Suppl):I46–I54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swijnenburg RJ, Schrepfer S, Cao F, et al. In vivo imaging of embryonic stem cells reveals patterns of survival and immune rejection following transplantation. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:1023–1029. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nussbaum J, Minami E, Laflamme MA, et al. Transplantation of undifferentiated murine embryonic stem cells in the heart: teratoma formation and immune response. FASEB J. 2007;21:1345–1357. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6769com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zwi L, Caspi O, Arbel G, et al. Cardiomyocyte differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2009;120:1513–1523. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.868885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Yamada S, Perez-Terzic C, Ikeda Y, Terzic A. Repair of acute myocardial infarction by human stemness factors induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2009;120:408–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, et al. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med. 2001;7:430–436. doi: 10.1038/86498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karamitsos TD, Francis JM, Myerson S, Selvanayagam JB, Neubauer S. The role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1407–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen IY, Wu JC Cardiovascular molecular imaging: focus on clinical translation. Circulation 123:425–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kiessling F (2008) Noninvasive cell tracking. Handb Exp Pharmacol (185 Pt 2):305–321. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77496-9_13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Semelka RC, Helmberger TK. Contrast agents for MR imaging of the liver. Radiology. 2001;218:27–38. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2491–2499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorek DLJ, Tsourkas A. Size, charge and concentration dependent uptake of iron oxide particles by non-phagocytic cells. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3583–3590. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernsen MR, Moelker AD, Wielopolski PA, van Tiel ST, Krestin GP Labelling of mammalian cells for visualisation by MRI. Eur Radiol 20:255–274. doi:10.1007/s00330-009-1540-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Arbab AS, Pandit SD, Anderson SA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and confocal microscopy studies of magnetically labeled endothelial progenitor cells trafficking to sites of tumor angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2006;24:671–678. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsiao JK, Chu HH, Wang YH, et al. Macrophage physiological function after superparamagnetic iron oxide labeling. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:820–829. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delcroix GJ, Jacquart M, Lemaire L, et al. Mesenchymal and neural stem cells labeled with HEDP-coated SPIO nanoparticles: in vitro characterization and migration potential in rat brain. Brain Res. 2009;1255:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farrell E, Wielopolski P, Pavljasevic P, et al. Cell labelling with superparamagnetic iron oxide has no effect on chondrocyte behaviour. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17:961–967. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magnitsky S, Walton RM, Wolfe JH, Poptani H. Magnetic resonance imaging detects differences in migration between primary and immortalized neural stem cells. Acad Radiol. 2008;15:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schafer R, Kehlbach R, Muller M, et al. Labeling of human mesenchymal stromal cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide leads to a decrease in migration capacity and colony formation ability. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:68–78. doi: 10.1080/14653240802666043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J-X, Tang W-L, Wang X-X. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles may affect endothelial progenitor cell migration ability and adhesion capacity. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:251–259. doi: 10.3109/14653240903446910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kostura L, Kraitchman DL, Mackay AM, Pittenger MF, Bulte JWM. Feridex labeling of mesenchymal stem cells inhibits chondrogenesis but not adipogenesis or osteogenesis. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:513–517. doi: 10.1002/nbm.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen I, Greve J, Gheysens O, et al. Comparison of optical bioluminescence reporter gene and superparamagnetic iron oxide MR contrast agent as cell markers for noninvasive imaging of cardiac cell transplantation. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:178–187. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amsalem Y, Mardor Y, Feinberg MS, et al (2007) Iron-Oxide Labeling and Outcome of Transplanted Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Infarcted Myocardium. Circulation 116(suppl):I-38-45. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.680231 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Winter EM, Hogers B, van der Graaf LM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE, van der Weerd L Cell tracking using iron oxide fails to distinguish dead from living transplanted cells in the infarcted heart. Magn Reson Med 63:817–821. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22094 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Terrovitis J, Stuber M, Youssef A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging overestimates ferumoxide-labeled stem cell survival after transplantation in the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:1555–1562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van den Bos EJ, Baks T, Moelker AD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of haemorrhage within reperfused myocardial infarcts: possible interference with iron oxide-labelled cell tracking? Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1620–1626. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brekke C, Morgan SC, Lowe AS, et al. The in vitro effects of a bimodal contrast agent on cellular functions and relaxometry. NMR Biomed. 2007;20:77–89. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aime S, Castelli DD, Crich SG, Gianolio E, Terreno E. Pushing the sensitivity envelope of lanthanide-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents for molecular imaging applications. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:822–831. doi: 10.1021/ar800192p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gianolio E, Arena F, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K, Hogset A, Aime S Photochemical activation of endosomal escape of MRI-Gd-agents in tumor cells. Magn Reson Med. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22586 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Bulte JW. In vivo MRI cell tracking: clinical studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:314–325. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamada M, Gurney PT, Chung J, et al. Manganese-guided cellular MRI of human embryonic stem cell and human bone marrow stromal cell viability. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:1047–1054. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilad AA, Walczak P, McMahon MT, et al. MR tracking of transplanted cells with “positive contrast” using manganese oxide nanoparticles. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:1–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tran LA, Krishnamurthy R, Muthupillai R, et al. Gadonanotubes as magnetic nanolabels for stem cell detection. Biomaterials 31:9482–9491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Srinivas M, Heerschap A, Ahrens ET, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ. (19)F MRI for quantitative in vivo cell tracking. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srinivas M, Morel PA, Ernst LA, Laidlaw DH, Ahrens ET. Fluorine-19 MRI for visualization and quantification of cell migration in a diabetes model. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:725–734. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Partlow KC, Chen J, Brant JA, et al. 19F magnetic resonance imaging for stem/progenitor cell tracking with multiple unique perfluorocarbon nanobeacons. FASEB J. 2007;21:1647–1654. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6505com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17:545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aicher A, Brenner W, Zuhayra M, et al. Assessment of the tissue distribution of transplanted human endothelial progenitor cells by radioactive labeling. Circulation. 2003;107:2134–2139. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062649.63838.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barbash IM, Chouraqui P, Baron J, et al. Systemic delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted myocardium: feasibility, cell migration, and body distribution. Circulation. 2003;108:863–868. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084828.50310.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou D, Youssef EA, Brinton TJ, et al. Radiolabeled cell distribution after intramyocardial, intracoronary, and interstitial retrograde coronary venous delivery: implications for current clinical trials. Circulation. 2005;112(9 Suppl):I150–I156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schachinger V, Aicher A, Dobert N, et al. Pilot trial on determinants of progenitor cell recruitment to the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2008;118:1425–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.777102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chin BB, Nakamoto Y, Bulte JW, Pittenger MF, Wahl R, Kraitchman DL. 111In oxine labelled mesenchymal stem cell SPECT after intravenous administration in myocardial infarction. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24:1149–1154. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brenner W, Aicher A, Eckey T, et al. 111In-labeled CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in a rat myocardial infarction model. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Penicka M, Lang O, Widimsky P, et al. One-day kinetics of myocardial engraftment after intracoronary injection of bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with acute and chronic myocardial infarction. Heart. 2007;93:837–841. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.091934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blackwood KJ, Lewden B, Wells RG, et al. In vivo SPECT quantification of transplanted cell survival after engraftment using (111)In-tropolone in infarcted canine myocardium. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:927–935. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitchell AJ, Sabondjian E, Sykes J, et al. Comparison of initial cell retention and clearance kinetics after subendocardial or subepicardial injections of endothelial progenitor cells in a canine myocardial infarction model. J Nucl Med 51:413–417. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069732 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Nowak B, Weber C, Schober A, et al. Indium-111 oxine labelling affects the cellular integrity of haematopoietic progenitor cells. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:715–721. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoon JK, Park BN, Shim WY, Shin JY, Lee G, Ahn YH In vivo tracking of 111In-labeled bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in acute brain trauma model. Nucl Med Biol 37:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Gholamrezanezhad A, Mirpour S, Ardekani JM, et al. Cytotoxicity of 111In-oxine on mesenchymal stem cells: a time-dependent adverse effect. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:210–216. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328318b328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rahmim A, Zaidi H. PET versus SPECT: strengths, limitations and challenges. Nucl Med Commun. 2008;29:193–207. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3282f3a515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doyle B, Kemp BJ, Chareonthaitawee P, et al. Dynamic tracking during intracoronary injection of 18F-FDG-labeled progenitor cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1708–1714. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hofmann M, Wollert KC, Meyer GP, et al. Monitoring of bone marrow cell homing into the infarcted human myocardium. Circulation. 2005;111:2198–2202. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163546.27639.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang WJ, Kang HJ, Kim HS, Chung JK, Lee MC, Lee DS. Tissue distribution of 18F-FDG-labeled peripheral hematopoietic stem cells after intracoronary administration in patients with myocardial infarction. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1295–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adonai N, Nguyen KN, Walsh J, et al. Ex vivo cell labeling with 64Cu-pyruvaldehyde-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) for imaging cell trafficking in mice with positron-emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3030–3035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052709599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Serganova I, Mayer-Kukuck P, Huang R, Blasberg R (2008) Molecular imaging: reporter gene imaging. Handb Exp Pharmacol (185 Pt 2):167–223. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77496-9_8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Kammili RK, Taylor DG, Xia J, et al. Generation of novel reporter stem cells and their application for non-invasive molecular imaging of cardiac-differentiated stem cells in vivo. Stem Cells Dev. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Ruggiero A, Brader P, Serganova I, et al. Different strategies for reducing intestinal background radioactivity associated with imaging HSV1-tk expression using established radionucleoside probes. Mol Imaging 9:47–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Wu JC, Chen IY, Sundaresan G, et al. Molecular imaging of cardiac cell transplantation in living animals using optical bioluminescence and positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2003;108:1302–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091252.20010.6E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cao F, Lin S, Xie X, et al. In vivo visualization of embryonic stem cell survival, proliferation, and migration after cardiac delivery. Circulation. 2006;113:1005–1014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berger C, Flowers ME, Warren EH, Riddell SR. Analysis of transgene-specific immune responses that limit the in vivo persistence of adoptively transferred HSV-TK-modified donor T cells after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:2294–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ponomarev V, Doubrovin M, Shavrin A, et al. A human-derived reporter gene for noninvasive imaging in humans: mitochondrial thymidine kinase type 2. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:819–826. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.036962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Terrovitis J, Kwok KF, Lautamaki R, et al. Ectopic expression of the sodium-iodide symporter enables imaging of transplanted cardiac stem cells in vivo by single-photon emission computed tomography or positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1652–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gray SJ, Samulski RJ. Optimizing gene delivery vectors for the treatment of heart disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:911–922. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.7.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ma Y, Ramezani A, Lewis R, Hawley RG, Thomson JA. High-level sustained transgene expression in human embryonic stem cells using lentiviral vectors. Stem Cells. 2003;21:111–117. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-1-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toelen J, Deroose CM, Gijsbers R, et al. Fetal gene transfer with lentiviral vectors: long-term in vivo follow-up evaluation in a rat model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(352):e351–e356. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krishnan M, Park JM, Cao F, et al. Effects of epigenetic modulation on reporter gene expression: implications for stem cell imaging. FASEB J. 2006;20:106–108. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4551fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mikkers H, Berns A. Retroviral insertional mutagenesis: tagging cancer pathways. Adv Cancer Res. 2003;88:53–99. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(03)88304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zurkiya O, Chan AW, Hu X. MagA is sufficient for producing magnetic nanoparticles in mammalian cells, making it an MRI reporter. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1225–1231. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gilad AA, McMahon MT, Walczak P, et al. Artificial reporter gene providing MRI contrast based on proton exchange. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:217–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Naumova AV, Reinecke H, Yarnykh V, Deem J, Yuan C, Charles EM Ferritin overexpression for noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging-based tracking of stem cells transplanted into the heart. Mol Imaging 9:201–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Wang J, Zhang S, Rabinovich B, et al. Human CD34+ cells in experimental myocardial infarction: long-term survival, sustained functional improvement, and mechanism of action. Circ Res 106:1904–1911. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Ly HQ, Hoshino K, Pomerantseva I, et al. In vivo myocardial distribution of multipotent progenitor cells following intracoronary delivery in a swine model of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2861–2868. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Muller-Borer BJ, Collins MC, Gunst PR, Cascio WE, Kypson AP. Quantum dot labeling of mesenchymal stem cells. J Nanobiotechnology. 2007;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lin S, Xie X, Patel MR, et al. Quantum dot imaging for embryonic stem cells. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:67. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rosen AB, Kelly DJ, Schuldt AJ, et al. Finding fluorescent needles in the cardiac haystack: tracking human mesenchymal stem cells labeled with quantum dots for quantitative in vivo three-dimensional fluorescence analysis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2128–2138. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hardman R. A toxicologic review of quantum dots: toxicity depends on physicochemical and environmental factors. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:165–172. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lovric J, Bazzi HS, Cuie Y, Fortin GR, Winnik FM, Maysinger D. Differences in subcellular distribution and toxicity of green and red emitting CdTe quantum dots. J Mol Med. 2005;83:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Qiao H, Zhang H, Zheng Y, et al. Embryonic stem cell grafting in normal and infarcted myocardium: serial assessment with MR imaging and PET dual detection. Radiology. 2009;250:821–829. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503080205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Higuchi T, Anton M, Dumler K, et al. Combined reporter gene PET and iron oxide MRI for monitoring survival and localization of transplanted cells in the rat heart. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1088–1094. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ray P, De A, Min JJ, Tsien RY, Gambhir SS. Imaging tri-fusion multimodality reporter gene expression in living subjects. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1323–1330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, et al. Improved clinical outcome after intracoronary administration of bone-marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction: final 1-year results of the REPAIR-AMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2775–2783. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Beitnes JO, Hopp E, Lunde K, et al. Long-term results after intracoronary injection of autologous mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction: the ASTAMI randomised, controlled study. Heart. 2009;95:1983–1989. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.178913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, et al. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2004;364:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: 5-year follow-up from the randomized-controlled BOOST trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2978–2984. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Meluzin J, Janousek S, Mayer J, et al. Three-, 6-, and 12-month results of autologous transplantation of mononuclear bone marrow cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chen SL, Fang WW, Ye F, et al. Effect on left ventricular function of intracoronary transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dill T, Schachinger V, Rolf A, et al. Intracoronary administration of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells improves left ventricular function in patients at risk for adverse remodeling after acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results of the Reinfusion of Enriched Progenitor cells And Infarct Remodeling in Acute Myocardial Infarction study (REPAIR-AMI) cardiac magnetic resonance imaging substudy. Am Heart J. 2009;157:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kraitchman DL, Heldman AW, Atalar E, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;107:2290–2293. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070931.62772.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Amado LC, Saliaris AP, Schuleri KH, et al. Cardiac repair with intramyocardial injection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells after myocardial infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11474–11479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504388102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stuckey DJ, Carr CA, Martin-Rendon E, et al. Iron particles for noninvasive monitoring of bone marrow stromal cell engraftment into, and isolation of viable engrafted donor cells from, the heart. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1968–1975. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ebert SN, Taylor DG, Nguyen HL, et al. Noninvasive tracking of cardiac embryonic stem cells in vivo using magnetic resonance imaging techniques. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2936–2944. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chapon C, Jackson JS, Aboagye EO, Herlihy AH, Jones WA, Bhakoo KK. An in vivo multimodal imaging study using MRI and PET of stem cell transplantation after myocardial infarction in rats. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s11307-008-0174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Li Z, Lee A, Huang M, et al. Imaging survival and function of transplanted cardiac resident stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]