Abstract

Identifying the Campylobacter genotypes that colonize farmed and wild ducks will help to assess the proportion of human disease that is potentially attributable to the consumption of duck meat and environmental exposure to duck faeces. Comparison of temporally and geographically matched farmed and wild ducks showed that they had different Campylobacter populations in terms of: (i) prevalence, (ii) Campylobacter species and (iii) diversity of genotypes. Furthermore, 92.4% of Campylobacter isolates from farmed ducks were sequence types (STs) commonly associated with human disease, in contrast to just one isolate from the wild ducks. Only one ST, ST-45, was shared between the two sources, accounting for 0.9% of wild duck isolates and 5% of farmed duck isolates. These results indicate that domestic ‘niche’ as well as host type may affect the distribution of Campylobacter, and that husbandry practises associated with intensive agriculture may be involved in generating a reservoir of human disease associated lineages.

Introduction

Campylobacter continues to be a major cause of bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide, with a reported incidence of 12.79/100 000 population in the USA and 51 488 reported cases in the UK in 2007 (HPA, 2008; Vugia et al., 2008). Although the disease is largely sporadic and self-limiting, more serious sequelae such as Guillain–Barrré syndrome and reactive arthritis can occasionally occur and the total annual economic burden has been estimated to be $8 billion in the USA and £500 million in the UK (Buzby and Roberts, 1997; Ketley, 1997; Nachamkin et al., 1998; Humphrey et al., 2007; Townes et al., 2008). In a UK study, 93% of human infection was caused by Campylobacter jejuni, with most of the remainder caused by Campylobacter coli (Gillespie et al., 2002). Campylobacter species can be isolated from the intestinal tract of many animals and birds and also from environmental sources such as water.

Approximately, 18 million ducks were produced in the UK in 2006 (Jones et al., 2009). While chicken is an important source of human infection, a UK study found 50.7% of duck meat to be contaminated with Campylobacter, which is comparable with chicken meat (60.9%), and another attributed 2% of Campylobacteriosis outbreaks to duck meat (Little et al., 2008; Sheppard et al., 2009). Other studies report duck meat contamination rates of 6–36% (depending on sample type) in Egypt, 31% in Thailand and 45.8% in Ireland (Khalafalla, 1990; Whyte et al., 2004; Boonmar et al., 2007). Pekin is currently the duck strain most commonly reared for commercial meat production and it originates from domestication of the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) (Rodenburg et al., 2005). Wild ducks also pose a potential health risk to humans, with reported Campylobacter carriage rates ranging from 13% to 75%, although models attribute a low proportion of human disease to environmental sources (Luechtefeld et al., 1980; Pacha et al., 1988; Obiri-Danso and Jones, 1999; Fallacara et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2008; Sheppard et al., 2009).

The aim of this observational study was to explore the potential of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) in describing and comparing the genetic diversity of Campylobacter colonizing domesticated (farmed) and wild Mallard ducks, using isolates from faecal samples. Identifying the genotypes colonizing farmed and wild ducks is necessary to assess the proportion of human disease attributable to consumption of duck meat, as opposed to environmental exposure to duck faeces such as in recreational water. The degree of difference between the populations in these two duck associated sources will determine whether genetic attribution models can differentiate between them. It also allows assessment of the extent to which there are duck associated Campylobacter genotypes and whether these are robust to the different ecology of these genetically similar groups of ducks.

Results and discussion

Campylobacter prevalence

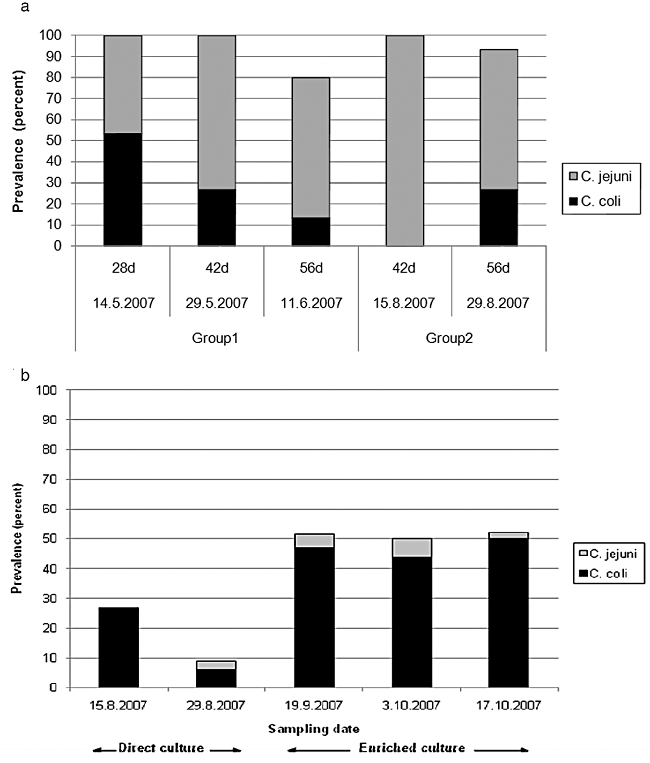

The prevalence of Campylobacter among two groups of 60 farmed ducks tested at 28–56 days of age was high (93.3–100%), and was similar to that seen in broiler chickens (Fig. 1) (Frost, 2001; Newell and Fearnley, 2003; Colles et al., 2008a). There are few other reports of on-farm prevalence of Campylobacter among domestically reared duck flocks, but one found rates to vary from 2.5% to 60% at 69–84 days of age and another recorded 100% colonization at 8 days of age (Kasrazadeh and Genigeorgis, 1987; McCrea et al., 2006). There was some evidence of a drop in Campylobacter colonization, both in prevalence and average numbers of colony-forming units (cfu) estimated by the Most Probable Number method, in the first group of farmed ducks between the ages of 42 (4.1 × 106 cfu g−1) and 56 (2.2 × 105 cfu g−1) days of age, and in numbers of cfu only (7.1 × 105 cfu g−1 at 42 days and 2.7 × 105 cfu g−1 at 56 days) in the second group. There was no significant difference in numbers of cfu evident between the two groups of ducks overall (P = 0.73). The changes could be a consequence of maturing immunity, seasonal differences or the dynamics of infection associated with the introduction of new Campylobacter genotypes (Wallace et al., 1997; 1998;).

Fig. 1.

The prevalence and proportion of Campylobacter species isolated from (a) two groups of 60 farmed ducks aged 28–56 days and (b) 60–100 wild Mallard ducks on five sampling occasions (August–October 2007). Faecal samples were collected from each of 15 pens containing four domesticated ducks and separated by wooden partitions at the University farm, Wytham (Jones et al., 2009). Wild ducks were sampled on a pond and subsidiary of the River Cherwell in the University Parks approximately 5 miles distant. Freshly voided faecal samples of consistent size and appearance were collected only from areas where Mallards had been observed resting immediately before. To minimize the chance of repeated sampling from the same animal, a cross section of each of the areas was sampled, adjacent specimens were avoided and fewer samples were collected than ducks counted on the pond. Campylobacter was isolated on mCCDA for direct culture, and Exeter broth and mCCDA for enriched culture, using standard techniques (Colles et al., 2009).

The prevalence of Campylobacter among the wild ducks was much lower (9.2–52.2%). The higher prevalence rates (50.0–52.2%) were recovered using enrichment broth but still below the prevalence in the farmed ducks (Fig. 1). Other studies report carriage rates of 13–75%, with levels lower among ducks feeding largely on vegetation compared with those straining the sediments of ponds (Luechtefeld et al., 1980; Pacha et al., 1988; Obiri-Danso and Jones, 1999; Fallacara et al., 2001). The conditions in which the farmed and wild birds live were of course very different, with Campylobacter prevalence among faecal droppings from the wild ducks likely to be influenced by more extreme differences in temperature, moisture and ultra-violet light levels (Obiri-Danso and Jones, 1999).

Campylobacter species and sequence type diversity

The Campylobacter species distribution was markedly different, with C. jejuni predominant among isolates from farmed ducks (average of 74.6%) and C. coli predominant among isolates from wild ducks (average of 85.7% using direct culture and 90.9% using enrichment culture) (Fig. 1). Species distribution differs in other reports, with C. jejuni being the principal species isolated in other studies of wild ducks and wild geese in the UK, while either C. coli or C. jejuni predominate among duck meat products (Obiri-Danso and Jones, 1999; Boonmar et al., 2007; Little et al., 2008; Colles et al., 2008b).

The STs and clonal complexes identified among 92 isolates from farmed ducks and 109 isolates from wild ducks are given in Table 1. Forty-seven STs were recovered from wild ducks, compared with 10 from farmed ducks. The average diversity index, D, over five sampling occasions was 0.54 (range 0.15–0.70) for the farmed ducks and 0.93 (range 0.91–0.96) for the wild ducks, with a zero value indicating that that all individuals within a population are identical and a value of one indicating that they are all different (Hunter, 1990). In order to obtain an indication of the diversity of Campylobacter carried by an individual bird, within the constraints of the microbiological sampling frame, up to 10 colonies were sequence typed from a small proportion of birds (ten farmed, four wild, on multiple sampling dates). Carriage of multiple STs was lower among farmed ducks (1–3 STs per bird, average D = 0.19, range 0–0.56) compared with wild ducks (1–5 STs per bird, average D = 0.42, range 0–0.86). Only one ST, the C. jejuni ST-45, with fine type flaA SVR allele 2, peptide 27, was shared between both host types, accounting for 0.9% of wild duck isolates and 5% of farmed duck isolates (Meinersmann et al., 1997; Dingle et al., 2002). This genotype is thought to show adaption for environmental survival and is frequently isolated from water (Kwan et al., 2008; Sopwith et al., 2008; Carter et al., 2009).

Table 1.

The C. jejuni and C. coli genotypes identified among isolates from temporally and geographically matched wild (n = 109) and farmed (n = 92) ducks sampled in Oxfordshire, UK

| Frequency | No. of sampling occasions present | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Clonal complex | ST | Wild | Farmed | |

| C. jejuni | ST-21 CC | 19 | 14 | 2 | |

| ST-42 CC | 42 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 447 | 12 | 3 | |||

| ST-45 CC | 45 | 1 | 34 | 2 | |

| ST-354 CC | 354 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ST-443 CC | 51 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ST-574 CC | 574 | 3 | 1 | ||

| ST-702 CC | 702 | 2 | 2 | ||

| ST-1287 CC | 945 | 7 | 1 | ||

| ST-1332 CC | 1276 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Unassigned | 3321 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 2221 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3322 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3536 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3534 | 1 | 1 | |||

| C. coli | ST-828CC | 827 | 15 | 3 | |

| 867 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Unassigned | 3311 | 14 | 3 | ||

| 1986 | 9 | 3 | |||

| 3306 | 9 | 2 | |||

| 3309 | 6 | 2 | |||

| 3319 | 6 | 1 | |||

| 1765 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 3304 | 4 | 3 | |||

| 3532 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 1764 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 2015 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 3821 | 3 | 1 | |||

| 1771 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 3305 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 3820 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 3314 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 3312 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 3308 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 1766 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1992 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3307 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3310 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3313 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3315 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3316 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3317 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3318 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3320 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3323 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3533 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3535 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3822 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3823 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3824 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3825 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3826 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3827 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3828 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3829 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3830 | 1 | 1 | |||

Up to 10 colonies were genotyped from a small proportion of birds (ten farmed, four wild) and those STs isolated multiple times from the same bird are not included, different STs isolated from the same bird are. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed using standard methods that have been previously published (Dingle et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2005).

No effects on ST distribution or diversity from wild ducks were observed using direct and enrichment methods in this study, over that which may be explained by natural turnover within the population. Six STs (one C. jejuni and five C. coli) were recovered at the same low frequency from both direct and enriched culture, while many more were seen on one occasion only, irrespective of the culture method used. Despite concerns that Exeter broth is more selective for C. jejuni due to its Polymixin B content, the predominant growth of C. coli from the wild ducks suggests that isolation of this species was not prevented in this case (Humphrey, 1989; Rodgers et al., 2010).

Comparison with other host sources

An equal number of C. jejuni STs were recovered from both farmed and wild ducks, but the majority (accounting for 92.4% of the isolates) from farmed ducks were those commonly associated with human disease and farm animal sources (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/), in contrast to just one such isolate (ST-45) from the wild ducks. Comparisons with large published population datasets indicated C. jejuni from farmed ducks showed largest overlap of STs with nationally sampled retail poultry meat (eight STs) (Sheppard et al., 2010) and to a lesser extent with free-range poultry previously sampled on the same farm (four STs) (Colles et al., 2008a), but no STs were shared with wild geese sampled on the same farm (Colles et al., 2008b). Another study similarly found a C. coli serotype common to duck and chicken meat (Little et al., 2008). Despite these findings, ST-945, accounting for 7.6% of isolates from farmed ducks and also previously isolated from human disease and chicken meat may have some unusual attributes, as it clusters into the ST-1287 clonal complex dominated by isolates from wild birds, most commonly ‘waders’ (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/). In contrast to the farmed ducks, the majority of C. jejuni STs from wild ducks showed potential host association, with four being unique to this study, and three being isolated from mallards and/or geese in Sweden, Scotland and/or Denmark between 2002 and 2009 (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter).

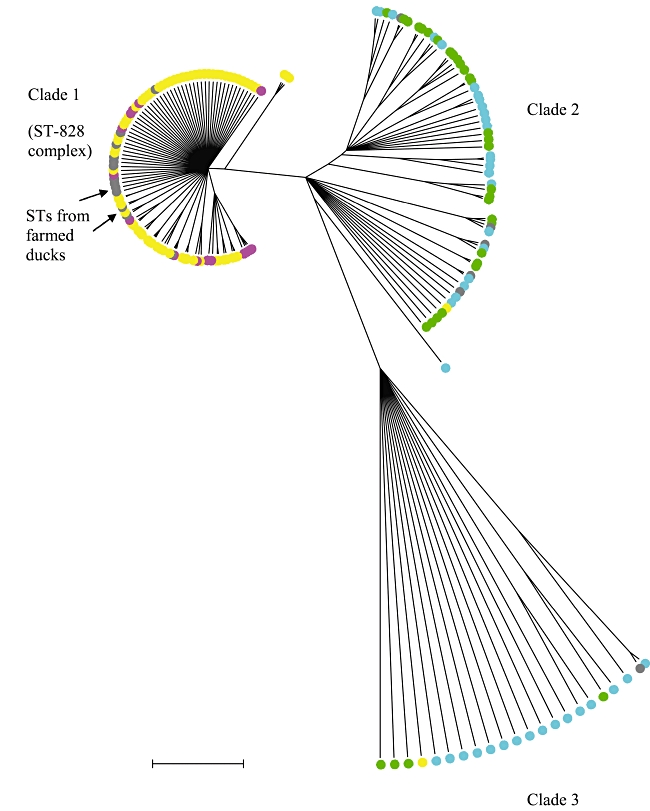

The majority (82.1%) of C. coli STs from the wild ducks have previously been unreported. Further, C. coli STs isolated from the wild ducks frequently contained alleles that were 4–8% divergent from the two C. coli STs isolated from farmed ducks and other members of the ST-828 complex predominant in human disease and farm animals, which is supported by the deep branching on the clonal frame tree (Fig. 2) (Didelot and Falush, 2007; Sheppard et al., 2008). Unlike C. jejuni, clonal complexes have rarely been identified among C. coli outside the major ST-828 complex, but seven clusters of two to six closely related STs were identified among the unassigned wild duck isolates and may potentially represent duck or water fowl host associated lineages. Those C. coli STs from the wild ducks that were not unique to this study had all previously been isolated solely from water sources. The C. coli population from wild ducks exhibited a very high genetic similarity to water isolates, including those sampled as geographically distant as Canada, with very strong support from FST analysis demonstrating 96% similarity at the nucleotide level, and a 99% predicted shared ancestry using structure (Wright, 1951; Pritchard et al., 2000; Falush et al., 2003; McCarthy et al., 2007). These isolates from wild ducks and water make up the majority of the two clades that have been recognized in C. coli outside of the ST-828 complex (Sheppard et al., 2008).

Fig. 2.

A 75% consensus clonal frame tree demonstrating the genetic relationships between C. coli isolates from farmed and wild ducks and other sources, using concatenated nucleotide sequence, 50 000 burn-in cycles and 100 000 further iterations (Didelot and Falush, 2007). Key: environmental water, blue; farmed ducks, highlighted with arrows; wild ducks, green; farmed chicken, pink; retail poultry meat, yellow; shared sources, grey.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

There is increasing evidence of strong host association among Campylobacter genotypes (McCarthy et al., 2007; Colles et al., 2008b; French et al., 2009; Sheppard et al., 2010); however, the results presented here give a preliminary indication that agricultural practices may alter the microbiota within a given host species, and/or provide an environment by which certain Campylobacter genotypes are favoured. It is possible that in developing the Pekin strain over many generations, the caecal function has become sufficiently different to the wild type that there are still affects of host association with the farm bred duck (Clench and Mathias, 1995). Alternatively, the farm environment leads to major differences in diet, age and population structure, immune function, stocking density and behaviours compared with that experienced by wild birds, all of which may affect Campylobacter prevalence and diversity. Transmission may be interrupted among wild birds through greater mixing of diverse individuals, but enhanced by rapid replenishment of relatively immature ducks in the domestic setting, potentially favouring bacterial flora adapted to such different dynamics. Large-scale sampling of environmental isolates such as these are essential in determining the population structure and natural ecology of Campylobacter, particularly C. coli, more fully. The results from this study are compatible with duck meat being a potential source of human infection and demonstrate the need for large-scale studies across the duck and other non-chicken poultry industries.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UK Department for Environmental, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), contract No. OZ0611, for funding the work along with continued maintenance of the Campylobacter PubMLST database (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/). The study was made possible by another DEFRA funded project, contract No. AW0935, and we are grateful to Dr Tracey Jones, Dr Corri Waitt, Prof Marian Dawkins and the Food Animal Initiative, Oxford for their help and provision of facilities. We also thank the Zoology Department Sequencing facility, and Dr Keith Jolley for IT support. Prof Martin Maiden is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow and Dr Samuel Sheppard a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow.

References

- Boonmar S, Yingsakmongkon S, Songserm T, Hanhaboon P, Passadurak W. Detection of Campylobacter in duck using standard culture method and multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:728–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzby JC, Roberts T. Economic costs and trade impacts of microbial foodbourne illness. World Health Stat Q. 1997;50:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PE, McTavish SM, Brooks HJ, Campbell D, Collins-Emerson JM, Midwinter AC, French NP. Novel clonal complexes with an unknown animal reservoir dominate Campylobacter jejuni isolates from river water in New Zealand. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6038–6046. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clench MH, Mathias JR. The avian cecum: a review. The Wilson Bulletin. 1995;107:93–121. [Google Scholar]

- Colles FM, Jones TA, McCarthy ND, Sheppard SK, Cody AJ, Dingle KE, et al. Campylobacter infection of broiler chickens in a free-range environment. Environ Microbiol. 2008a;10:2042–2050. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles FM, Dingle KE, Cody AJ, Maiden MC. Comparison of Campylobacter populations in wild geese with those in starlings and free- range poultry on the same farm. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008b;74:3583–3590. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02491-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles FM, McCarthy ND, Howe JC, Devereux CL, Gosler AG, Maiden MC. Dynamics of Campylobacter colonization of a natural host, Sturnus vulgaris (European starling) Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:258–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175:1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle KE, Colles FM, Wareing DRA, Ure R, Fox AJ, Bolton FJ, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:14–23. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.14-23.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle KE, Colles FM, Ure R, Wagenaar J, Duim B, Bolton FJ, et al. Molecular characterisation of Campylobacter jejuni clones: a rational basis for epidemiological investigations. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:949–955. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.02-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallacara DM, Monahan CM, Morishita TY, Wack RF. Fecal shedding and antimicrobial susceptibility of selected bacterial pathogens and a survey of intestinal parasites in free-living waterfowl. Avian Dis. 2001;45:128–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French NP, Midwinter A, Holland B, Collins-Emerson J, Pattison R, Colles F, Carter P. Molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from wild-bird fecal material in children's playgrounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:779–783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01979-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JA. Current epidemiological issues in human campylobacteriosis. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;90:85S–95S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie IA, O'Brien SJ, Frost JA, Adak GK, Horby P, Swan AV, et al. A case-case comparison of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni infection: a tool for generating hypotheses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:937–942. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.10.3201/eid0809.010187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HPA. Health Protection Report. 2008. [WWW document]. URL http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2008/news2808.htm.

- Humphrey T, O'Brien S, Madsen M. Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;117:237–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey TJ. An appraisal of the efficacy of pre-enrichment for the isolation of Campylobacter jejuni from water and food. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;66:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter PR. Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1903–1905. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1903-1905.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Waitt CD, Dawkins MS. Water off a duck's back: showers and troughs match ponds for improving duck welfare. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2009;116:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kasrazadeh M, Genigeorgis C. Origin and prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni in ducks and duck meat at the farm and processing level. J Food Prot. 1987;50:321–326. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-50.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketley JM. Pathogenesis of enteric infection by Campylobacter. Microbiology. 1997;143:5–21. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalafalla FA. Campylobacter jejuni in poultry giblets. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1990;37:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1990.tb01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan PS, Barrigas M, Bolton FJ, French NP, Gowland P, Kemp R, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni populations in dairy cattle, wildlife, and the environment in a farmland area. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5130–5138. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02198-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little CL, Richardson JF, Owen RJ, de Pinna E, Threlfall EJ. Prevalence, characterisation and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter and Salmonella in raw poultrymeat in the UK, 2003-2005. Int J Environ Health Res. 2008;18:403–414. doi: 10.1080/09603120802100220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luechtefeld NA, Blaser MJ, Reller LB, Wang WL. Isolation of Campylobacter fetus subsp. jejuni from migratory waterfowl. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;12:406–408. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.3.406-408.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy ND, Colles FM, Dingle KE, Bagnall MC, Manning G, Maiden MC, Falush D. Host-associated genetic import in Campylobacter jejuni. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:267–272. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea BA, Tonooka KH, VanWorth C, Atwill ER, Schrader JS. Colonizing capability of Campylobacter jejuni genotypes from low- prevalence avian species in broiler chickens. J Food Prot. 2006;69:417–420. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinersmann RJ, Helsel LO, Fields PI, Hiett KL. Discrimination of Campylobacter jejuni isolates by fla gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2810–2814. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2810-2814.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WG, On SL, Wang G, Fontanoz S, Lastovica AJ, Mandrell RE. Extended multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. helveticus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2315–2329. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2315-2329.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachamkin I, Allos BM, Ho T. Campylobacter species and Guillain–Barré syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:555–567. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell DG, Fearnley C. Sources of Campylobacter colonization in broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4343–4351. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4343-4351.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiri-Danso K, Jones K. Distribution and seasonality of microbial indicators and thermophilic campylobacters in two freshwater bathing sites on the River Lune in northwest England. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:822–832. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacha RE, Clark GW, Williams EA, Carter AM. Migratory birds of central Washington as reservoirs of Campylobacter jejuni. Can J Microbiol. 1988;34:80–82. doi: 10.1139/m88-015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg TB, Bracke MBM, Berk J, Cooper J, Faure JM, Guenene D, et al. Welfare of ducks in European duck husbandry systems. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2005;61:633–646. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JD, Clifton-Hadley FA, Marin C, Vidal AB. An evaluation of survival and detection of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli in broiler caecal contents using culture-based methods. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109:1244–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard SK, McCarthy ND, Falush D, Maiden MC. Convergence of Campylobacter species: implications for bacterial evolution. Science. 2008;320:237–239. doi: 10.1126/science.1155532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard SK, Dallas JF, Strachan NJ, MacRae M, McCarthy ND, Wilson DJ, et al. Campylobacter genotyping to determine the source of human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1072–1078. doi: 10.1086/597402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard SK, Colles F, Richardson J, Cody AJ, Elson R, Lawson A, et al. Host association of Campylobacter genotypes transcends geographic variation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5269–5277. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00124-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopwith W, Birtles A, Matthews M, Fox A, Gee S, Painter M, et al. Identification of potential environmentally adapted Campylobacter jejuni strain, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1769–1773. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.071678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townes JM, Deodhar AA, Laine ES, Smith K, Krug HE, Barkhuizen A, et al. Reactive arthritis following culture-confirmed infections with bacterial enteric pathogens in Minnesota and Oregon: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1689–1696. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vugia D, Cronquist A, Hadler J, Tobin-D'Angelo M, Blythe D, Smith K, et al. Preliminary FoodNet Data on the Incidence of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food – 10 States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:366–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JS, Stanley KN, Currie JE, Diggle PJ, Jones K. Seasonality of thermophilic Campylobacter populations in chickens. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JS, Stanley KN, Jones K. The colonisation of turkeys by thermophilic Campylobacters. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:224–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte P, McGill K, Cowley D, Madden RH, Moran L, Scates P, et al. Occurrence of Campylobacter in retail foods in Ireland. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;95:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DJ, Gabriel E, Leatherbarrow AJH, Cheesbrough J, Gee S, Bolton E, et al. Tracing the source of campylobacteriosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;26:e1000203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. The genetical structure of populations. Ann Eugen. 1951;15:323–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1949.tb02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]