Abstract

Aim:

The effect of monotherapy with racemic salbutamol and levosalbutamol on symptoms, quality of life, and pulmonary function has been assessed and compared in mild persistent asthma.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized, open, parallel clinical study was conducted on 60 patients of mild persistent asthma. After baseline assessments, salbutamol was prescribed to 30 patients and levosalbutamol to another 30 for 4 weeks. The efficacy variables were change in asthma symptom scoring, pulmonary function test, and Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ) scoring. At follow-up, the patients were re-evaluated and analyzed by statistical tools.

Results:

Shortness of breath (P<0.001), chest tightness (P=0.033), wheeze (P=0.01), cough (P=0.024), and overall asthma symptom score (P<0.001) were significantly decreased in the levosalbutamol group in comparison to the salbutamol group. Results of MiniAQLQ revealed that improvement in symptoms (P=0.018), activity limitations (P=0.03), environmental stimuli (P=0.013)-related scoring and overall MiniAQLQ scoring (P<0.001) was statistically significant in the levosalbutamol group. Percentage reversibility of forced expiratory volume at one second (P=0.034), forced vital capacity (P=0.029), peak expiratory flow rate (P=0.0003) was found to be superior in the levosalbutamol group.

Conclusion:

Levosalbutamol was found to be superior compared to recemic salbutamol in mild persistent asthma.

KEY WORDS: Asthma symptom score, levosalbutamol, mild persistent asthma, miniAQLQ, pulmonary function test, salbutamol

Introduction

Asthma is a complex syndrome that involves potentially permanent airway obstruction, airway hyperresponsiveness, and multicellular inflammation. It is characterized by dyspnea, cough, chest tightness, wheezing, variable airflow obstruction, and airway hyper-responsiveness. The clinical diagnosis of asthma can be corroborated by suggestive changes in pulmonary function tests. Chronic asthma is defined as asthma requiring maintenance treatment. When patients complain of symptoms more than once weekly but less than once daily with normal or near normal lung function, it is called mild persistent asthma.[1]

The prevalence of asthma has increased in most countries since the 1970s. About 300 million people worldwide have asthma and by 2025 it has been estimated that a further 100 million will be affected.[2] There is a noticeable increase in health care burden from asthma in several areas of the world. There is also a global concern on the change in asthma epidemiology and clinical spectrum.[3] Well-controlled asthma reduces the burden for patients and health services. Control of asthma may mean minimal symptoms and freedom from exacerbations for patients, normal peak flow or low scores on standard questionnaire for doctors, or composite measures in clinical trials. The aims of pharmacological management of asthma are the control of symptoms, including nocturnal symptoms and exercise-induced asthma, prevention of exacerbations and the achievement of best possible pulmonary function, with minimal side effects.[2]

Salbutamol, the most widely used short-acting β2-agonist, consists of a racemic mixture of equal amounts of two enantiomers, (R)-salbutamol and (S)-salbutamol. The bronchodilator effects of salbutamol are attributed entirely to (R)-salbutamol (levosalbutamol), while (S)-salbutamol has been shown to possess bronchospastic and pro-inflammatory effects both in vitro and in vivo studies.[4] R-salbutamol administered as a single enantiomer has a better therapeutic ratio than racemic salbutamol. Handley et al reported that nebulized levosalbutamol, in doses yielding comparable bronchodilatation, had fewer β-agonist-mediated side effects than nebulized racemic salbutamol. Salbutamol is metabolized in human tissues by sulfation mainly in liver, and inactive metabolites produced are rapidly excreted in urine. Rates of metabolism for two isomers are different; R-isomer is metabolized about eight times faster than S-salbutamol, leading to a longer half-life and increased accumulation of S- salbutamol in tissues. In outpatient studies, asthma patients who were treated with levosalbutamol experienced a significantly greater increase in FEV1, a longer duration of action, and fewer side effects.[5–8]

Mild persistent asthma is usually treated with daily use of low dose inhaled corticosteroids along with short-acting β2-agonist. The use of regular short-acting β2-agonists without concurrent inhaled corticosteroids is now considered to be associated with increased exacerbations while it is relatively safe for a short-term treatment. In this study we desired to explore the possibility of short-term monotherapy with levosalbutamol in mild persistent asthma. The justification of this study was the theoretical argument that levosalbutmol may cause less tachyphylaxis in comparison to recemic salbutamol and hence it may have a valuable role in persistent asthma. The aim of this study was to explore and compare the efficacy and safety of levosalbutamol and racemic salbutamol, both administered by a pressurized meter dose inhaler (pMDI) in subjects with mild persistent bronchial asthma.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study was conducted on 60 patients of mild persistent asthma attending the outdoor department of Pulmonology of our institute. The study population included patients irrespective of sex, aged between 18 and 70 years suffering from mild persistent asthma with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 80% or more of the predicted value before administration of a bronchodilator; and a reversibility of airway obstruction by 12% or more with the use of a β2 agonist. Smokers, patients having an acute asthma exacerbation 4 weeks prior to the start of the study, patients already received steroids, and pregnant and lactating women were excluded from the study.

Study Design

The present study is a 4-week, randomized, open, parallel group comparative clinical study between racemic salbutamol and levosalbutamol in patients with mild persistent asthma conducted at a single centre. The study was approved by Institute Ethical Committee and procedures followed in this study are in accordance with the ethical standard laid down by ICMR's ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human subjects (2006). A written informed consent was obtained from all the patients who participated in the study after explaining the patient's diagnosis, the nature and purpose of a proposed treatment, the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment (salbutamol/levosalbutamol), alternative treatment and the risks and benefits of the alternative treatment. Randomization was done by using computer generated random list. After randomization, the patients were divided into two treatment groups. A total of 30 patients were allocated in the salbutamol group who received salbutamol 100 μg twice daily via pMDI and another 30 patients in the levosalbutamol group who received levosalbutamol 50 μg twice daily via pMDI for 4 weeks. As use of pMDI is technique dependent, the inhaler technique was taught to each patient. At the first visit, after detailed history on baseline symptomatology, clinical evaluation [asthma symptom score and mini asthma quality of life questionnaire (MiniAQLQ) scoring] and laboratory investigations (pulmonary function test) were done. After 4 weeks, pulmonary function test was repeated and clinical improvement was assessed in terms of change in pulmonary function test, asthma symptom score and MiniAQLQ scoring.

Efficacy and Safety Variables

The efficacy variables were change in the severity of asthma symptom score, pulmonary function test and MiniAQLQ scoring from baseline to day 28. Asthma symptom scoring has been considered as the primary outcome of this study.

Improvement in the five most important asthma symptoms (shortness of breath, chest tightness, wheeze, cough, mucus production) was scored on a scale of 0--3 depending on severity to assess the efficacy of the candidate drugs. The symptom severity was defined as follows: 0 = No symptoms; 1 =Mild (symptoms are present occasionally and patients can continue with daily activities); 2 = Moderate (symptoms are present most of the time but patients can perform daily activities); 3 = Severe/Incapacitating (symptoms are severe and affect daily activities or patient cannot do things that they normally can).[9]

The asthma quality of life questionnaire was designed as an evaluative instrument that would be sensitive to small within subject changes overtime and therefore appropriate for capturing the effect of an intervention in a clinical study. The shorter and simpler MiniAQLQ, with 15 questions, was developed to meet the need for greater efficiency in clinical studies, group patient monitoring and large surveys, where the measurement precision of the AQLQ is not quite so important. MiniAQLQ consists of four domains: questions related to symptoms, activity limitations, emotional function, and environmental stimuli. Scoring is done according to response options on scale of 1--7 (all of the time, most of the time, a lot of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, hardly any of the time, none of the time for question number 1--11; totally limited, extremely limited, very limited, moderate limitation, some limitation, a little limitation, not at all limited for question number 12--15).[10–13]

A pulmonary function test was done by a Maestros spirometer where flow measurements were done by using Terbium followed by computerized analysis. FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second), FVC (forced vital capacity), and PEFR (peak expiratory flow rate) were assessed at both visits.

Tolerability was assessed in terms of reported adverse experiences and vital signs, which were measured at baseline and at the end of the study. All reported adverse drug events were graded according to The National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) and compared between the groups.[14]

Statistical Analysis

The statistical calculation for the paired t-test, unpaired t-test, and Fischer's exact test were performed with statistical software Instat+ version 3.036 (Statistical Services Centre, University of Reading, UK). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Considering the Asthma symptom scoring as the primary outcome, the sample size has been calculated taking the level of significance (α) as 0.05, power of the study (1 – β) as 0.80, and expected mean difference 1.25. The statistician was blinded to the groups during analysis.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Demographics

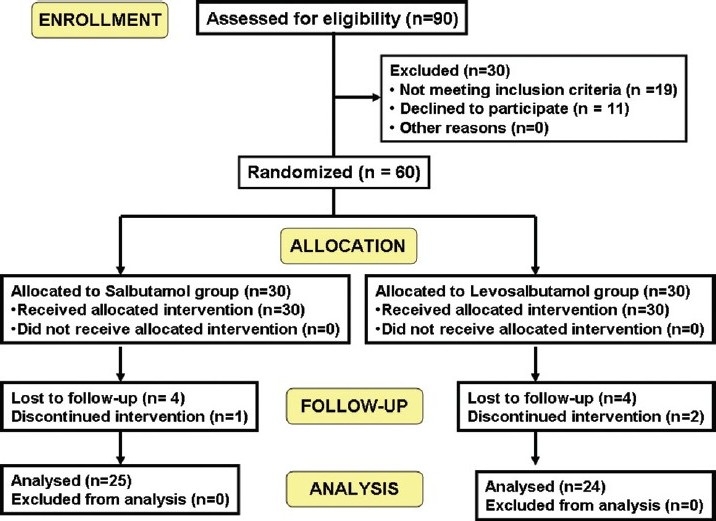

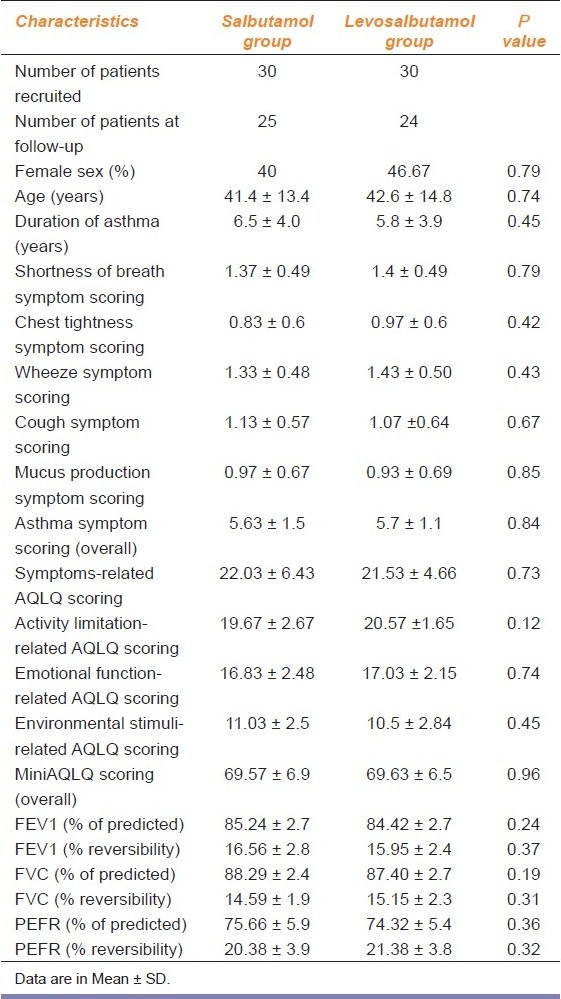

A total of 90 patients were assessed for eligibility following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Among them, 19 patients were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria and another 11 patients declined to participate in the study. So finally a total of 60 patients were randomized to two groups to receive either racemic salbutamol (n = 30) or levosalbutamol (n = 30). Postbaseline values were missing in 11 patients (5 in the salbutamol group and 6 in the levosalbutamol group) because they were lost to follow-up due to noncompliance [Figure 1]. The treatment groups were comparable in demographic features and baseline clinical characteristics [Table 1]. The patients ranged in age from 18 to 70 years (mean age, 41 years in the salbutamol group and 43 years in the levosalbutamol group), and 43% were female and 57% male. The mean duration of asthma symptoms was 6.5 years in the salbutamol group and 5.8 years in the levosalbutamol group.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data and clinical characteristics of the 60 patients of mild persistent asthma who participated in the study

Efficacy Analysis

Change in asthma symptoms

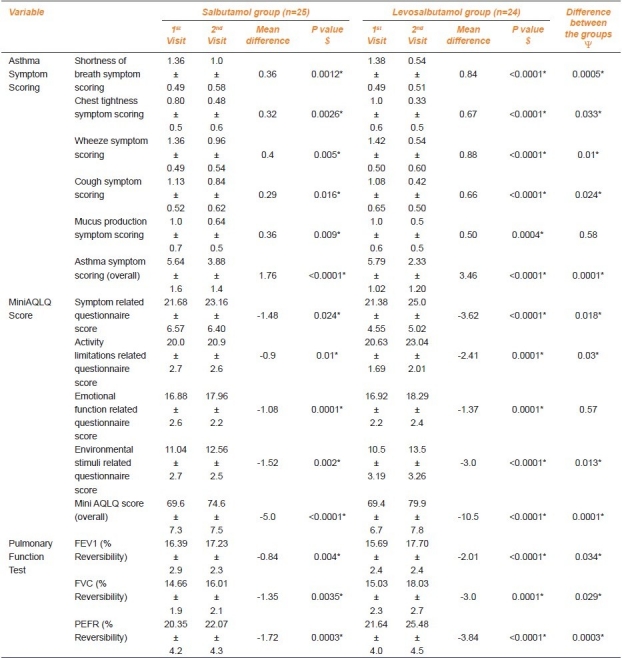

There was a 26.5% decrease in shortness of breath, 40% decrease in chest tightness, 29.4% decrease in wheeze, 25.7% decrease in cough, 36% decrease in mucus production score in the salbutamol group. In the levosalbutamol group, there was a decrease of 60.9% in shortness of breath, 67% in chest tightness, 61.9% in wheeze, 61.1% in cough, and 50% in mucus production. The changes in both groups were statistically significant and when the mean differences in two groups were compared by unpaired t-test, the difference between the salbutamol group and the levosalbutamol group was found to be statistically significant (P<0.05) in all parameters except mucus production. There was a 31.2% decrease in overall asthma symptom scoring in the salbutamol group and a 59.8% decrease in the levosalbutamol group. The changes in both groups were statistically significant and the change in the levosalbutamol group was found to be statistically significant (P=0.0001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Change in asthma symptom scoring, MiniAQLQ score, and pulmonary function test in follow-up patients (n=49) after 4 weeks.

Change in MiniAQLQ score

There was 2.4% increase in the symptom-related questionnaire score, 4.5% increase in activity limitations, 6.4% increase in emotional function, 13.8% increase in environmental stimuli-related questionnaire score in the salbutamol group. In the levosalbutamol group there was an increase of 16.9% in the symptom-related questionnaire score, 11.7% in activity limitations, 8.1% in emotional function, 28.6% in the environmental stimuli-related questionnaire score. The changes in both groups were statistically significant and the change in the levosalbutamol group was found to be statistically significant (P<0.05) in all parameters except emotional function-related questionnaire scoring. There was a 7.2% increase in the overall MiniAQLQ score in the salbutamol group and a 15.1% increase in the levosalbutamol group. The changes in both groups were statistically significant and the change in the levosalbutamol group was found to be statistically significant (P=0.0001) [Table 2].

Change in pulmonary function test

There was a positive mean difference of 0.84% in FEV1 (% reversibility), 1.35% in FVC (% reversibility), 1.72% in PEFR (% reversibility) in the salbutamol group whereas in the levosalbutamol group those values were 2.01%, 3%, and 3.84% respectively. The changes in both groups were statistically significant and when the mean differences in two groups were compared, the change in the levosalbutamol group was found to be statistically significant (P<0.05) [Table 2].

Safety Analysis

Both the drugs were well tolerated. In the salbutamol group, out of 10 patients who experienced adverse effects, 2 complained of headache, 1 had nausea/vomiting, 3 patients complained of muscular tremor and other 4 had experienced palpitation. In the levosalbutamol group 1 complained of headache, 1 patient had nausea, 1 patient had tremor, and 1 patient had palpitation.

According to CTC grading of adverse drug reactions, all the reported side effects were of grade 1 (mild). To compare the incidence of adverse effects of two groups Fischer's exact test was done and it was found to be statistically nonsignificant (P=0.11).

Discussion

In addition to the considerable economic burden of asthma, there are physical, emotional, and social effects, leading to reduced quality of life (QoL) of patients and their families.[15] The goal of treatment of asthma is to improve patients’ quality of life by providing rapid relief of symptoms and reducing the severity and number of recurrent episodes and this is measured as improvement of asthma symptoms score. In this study shortness of breath, chest tightness, wheeze, and cough were significantly decreased in the levosalbutamol group in comparison to the salbutamol group. The overall asthma symptom score improved significantly with levosalbutamol than salbutamol. Improvement in all four domains of MiniAQLQ was found with both the drugs. A comparative study revealed that improvement in symptoms, activity limitations, and environmental stimuli-related questionnaire scoring was significantly greater in the levosalbutamol group in comparison to the salbutamol group. Overall MiniAQLQ scoring was increased in the levosalbutamol group and the improvement was superior to salbutamol. The changes in three most important parameters, i.e., FEV1, FVC, and PEFR, were found to be significant in both groups. Percent reversibility of FEV1, FVC, PEFR was found to be superior in the levosalbutamol group in comparison to the salbutamol group. Both the drugs were well tolerated and there was no significant difference in incidence of adverse events.

The superiority of levosalbutamol over racemic salbutamol found in our study has been supported or explained by many clinical studies. Large, well-controlled clinical studies performed in adults with asthma have shown that nebulized levosalbutamol 1.25 mg produces greater bronchodilation than the standard 2.5 mg dose of racemic salbutamol. Lower dosing of the R-salbutamol isomer to patients with the use of levosalbutamol provides comparable or superior bronchodilation as racemic salbutamol, with the potential for fewer β-receptor mediated side effects. Both clinical trials and preclinical experiments have suggested that the inclusion of S-salbutamol in racemic salbutamol provides no clinical benefit and may oppose some of the therapeutic benefits of the R-isomer (levosalbutamol).[16,17]

Until recently S-salbutamol was considered inert filler in the racemic mixture; but animal as well as human studies have shown that S-salbutamol is not inert, rather it may have some deleterious effects. R-salbutamol is metabolized up to 12 times faster than S-salbutamol. Thus enantioselective metabolism of salbutamol leads to higher and sustained plasma levels of S-salbutamol with repeated dosing. There have been concerns that chronic use of racemic salbutamol may lead to loss of effectiveness and clinical deterioration. Formulation of salbutamol containing only R-isomer (levosalbutamol) has been available in international market since the last few years. Clinical trials in acute as well as chronic asthma in adults as well as children have shown that it has therapeutic advantage over racemic salbutamol and also is more cost effective.[18,19]

Several mechanisms may explain the superior efficacy of levosalbutamol over racemic salbutamol in asthma. It may be due to competitive inhibition between the enantiomers at beta-adrenoceptors or it may be attributed to additional anti-inflammatory properties of levosalbutamol.[19] Many in vitro and in vivo studies proved that levosalbutamol suppresses pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., peroxidase, superoxide, IL-2, IL-5, IL-13, IFN-γ, and granulocyte-macrophage - colony stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) in human eosinophils, T cells, and airway smooth muscle cells.[20–23] It also increases intracellular cAMP levels and inhibits cell proliferation by activation of the cAMP/protein kinase A pathway with simultaneous inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3’-OH (PI-3) kinase and nuclear factor (NF)-κB expression in human airway smooth muscle cells (HASMCs).[24,25] It increases inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA and decreases GM-CSFmRNA and protein release in human airway epithelial cells;[26] and amplifies the anti-inflammatory effect of glucocorticoids on suppression of GM-CSF in HASMCs.[22]

Conclusion

In conclusion, from the results of the present comparative clinical study of racemic salbutamol and levosalbutamol, levosalbutamol would be a better choice in mild persistent asthma compared with recemic salbutamol owing to its better efficacy and safety profile. Because the study had the limitations of being nonblinded and conducted in single-centre, the findings of this exploratory study should be confirmed by multicentric, randomized, double-blind, large population studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to Elizabeth F. Juniper, Professor, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Canada for sending the AQLQ free of cost for our study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Institutional research fund.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees J. Asthma control in adults. BMJ. 2006;332:767–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7544.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D’Souza GA, Gupta D, Jindal SK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for bronchial asthma in Indian adults: multicentre study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jantikar A, Brashier B, Maganji M, Raghupathy A, Mahadik P, Gokhale P, et al. Comparison of bronchodilator responses of levosalbutamol and salbutamol given via a pressurized metered dose inhaler: a randomized, double blind, single-dose, crossover study. Respir Med. 2007;101:845–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gawchik SM, Saccar CL, Noonan M, Reasner DS, DeGraw SS. The safety and efficacy of nebulized levalbuterol compared with racemic albuterol and placebo in the treatment of asthma in pediatric patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:615–21. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handley DA, Tinkelman D, Noonan M, Rollins TE, Snider ME, Caron J. Dose-response evaluation of levalbuterol versus racemic albuterol in patients with asthma. J Asthma. 2000;37:319–27. doi: 10.3109/02770900009055455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milgrom H, Skoner DP, Bensch G, Kim KT, Claus R, Baumgartner RA Levalbuterol Pediatric Study Group. Low-dose levalbuterol in children with asthma: safety and efficacy compared with placebo and racemic albuterol. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:938–45. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.120134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson HS, Bensch G, Pleskow WW, DiSantostefano R, DeGraw S, Reasner DS, et al. Improved bronchodilation with levalbuterol compared to racemic albuterol in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:943–52. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cakmak G, Demir T, Gemicioglu B, Aydemir A, Serdaroglu E, Donma O. The effect of add-on zafirlukast treatment to budesonide on bronchial hyperresponsiveness and serum levels of eosinophilic cataonic protein and total antioxidant capacity in asthmatic patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;204:249–56. doi: 10.1620/tjem.204.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juniper EF, Buist AS, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Validation of a standardized version of the asthma quality of life questionnaire. Chest. 1999;115:1265–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.5.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:32–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juniper EF. Health-related quality of life in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:105–10. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juniper EF. Effect of asthma on quality of life. Can Respir J. 1998;5(Suppl A):77A–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) Version 2.0. [Last accessed on 1999 Apr 30]. Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcv20_4-30-992.pdf .

- 15.Holgate ST, Price D, Valovirta E. Asthma out of control? A structured review of recent patient surveys. BMC Pulm Med. 2006;6(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-6-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson HS, Bensch G, Pleskow WW, DiSantostefano R, DeGraw S, Reasner DS, et al. Improved bronchodilation with levalbuterol compared with racemic albuterol in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:943–52. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalonzo GE., Jr Levalbuterol in the treatment of patients with asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104:288–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta MK, Singh M. Evidence based review on levosalbutamol. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:161–7. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulton DW, Fawcett JP. The pharmacokinetics of levosalbutamol: what are the clinical implications? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:23–40. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leff AR, Herrnreiter A, Naclerio RM, Baroody FM, Handley DA, Muñoz NM. Effect of enantiomeric forms of albuterol on stimulated secretion of granular protein from human eosinophils. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 1997;10:97–104. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1997.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baramki D, Koester J, Anderson AJ, Borish L. Modulation of T-cell function by (R)- and (S)-isomers of albuterol: anti-inflammatory influences of (R)-isomers are negated in the presence of the (S)-isomer. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:449–54. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.122159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ameredes BT, Calhoun WJ. Modulation of GM-CSF release by enantiomers of beta-agonists in human airway smooth muscle. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volcheck GW, Kelkar P, Bartemes KR, Gleich GJ, Kita H. Effects of (R)- and (S)-isomers of beta-adrenergic agonists on eosinophil response to interleukin-5. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1341–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agrawal DK, Ariyarathna K, Kelbe PW. (S)-albuterol activates pro-constrictory and pro-inflammatory pathways in human bronchial smooth muscle cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibe BO, Portugal AM, Raj JU. Levalbuterol inhibits human airway smooth muscle cell proliferation: therapeutic implications in the management of asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;139:225–36. doi: 10.1159/000091168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chorley BN, Li Y, Fang S, Park JA, Adler KB. (R)-albuterol elicits anti-inflammatory effects in human airway epithelial cells via iNOS. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:119–27. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0338OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]