Abstract

Objective:

To assess the renoprotective activity of the water extract of Annona squamosa in 5/6 nephrectomized animals.

Materials and Methods:

For evaluating the renoprotective effects of Annona squamosa, 5/6 nephrectomized rats were used as a model for renal failure. The effects of hot-water extract of leaves of Annona squamosa L. (A. squamosa) at a dose 300 mg/kg bw on biochemical and urinary parameters like plasma urea, plasma creatinine, and urine creatinine were analyzed. For elucidating its effect on oxidative stress, renal superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels were measured.

Results:

Nephrectomized rats (5/6) showed a significant rise in plasma urea and creatinine levels with a stable fall in urine creatinine. Treatment with A. squamosa extract (300 mg/kg bw) lead to a significant fall in the plasma urea and creatinine values with partial restoration to normal values along with a significant rise in the activity of SOD.

Conclusion:

Thus, therapeutic strategies against oxidative stress could be effective in renal diseases. This study provides an indication to investigate further the efficacy of A. squamosa as a novel agent for alleviating renal failure.

KEY WORDS: Annona squamosa, anti-oxidant, renal failure

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been implicated as important mediators in the progression of renal failure.[1] Compensatory mechanisms do exist, but these adaptations prove detrimental ultimately.[2] It has also been shown that oxidative stress and ROS formation play an important role in the pathophysiology of a variety of clinical and experimental renal diseases.[3] Studies have demonstrated augmentation of ROS and decreased serum antioxidative activity in patients suffering from renal diseases.[4]

Annona species belongs to custard apple family and is cultivated all over India. All parts are used in herbal medicine and it is found to be a good source of natural anti-oxidants. Its leaves and stem contstituents include various aporphine alkaloids.[5] Some reports have shown that leaves of Annona species exhibit antioxidant activity in different in vitro models due to the presence of flavanoids like rutin and hyperoside.[6] However, no reports are available to show the renoprotective effect of Annona species. We, therefore, aimed to investigate the effects of aqueous extracts of Annona squamosa (L.) in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. This study evaluated the efficacy of Annona species in ameliorating renal failure by the virtue of its antioxidant activity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wistar-kyoto male rats of eight weeks age with the body weight range of 250-300 gm were used. They were maintained under controlled temperature (<30° C) and humidity (<70%) with 12 hour day - night cycle according to the norms of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA). Male rats were used as many studies suggest that in animal models of chronic renal disease, males show accelerated progression of renal injury compared with females.[7] Each rat was housed in a plastic cage individually and had free access to autoclaved, untreated tap water, and standard rat chow (Pranav Agro Ltd, Ahmedabad, India). After surgery, rats were inspected daily for the level of activity and healing of surgical wounds.

Preparation of Plant Extract

Leaves of A. squamosa were collected during December 2009 from Visnagar, Gujarat. These were washed with water and 50 g of fresh leaves (kept at 25C for 5 days in absence of sunlight) were extracted in 1 l of boiling water for 2 h and concentrated to half of the volume by boiling in a water bath. The dark-brown extract thus obtained was cooled, filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the filtrate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 25° C. The supernatant was concentrated up to 100 ml on rotavapour under reduced pressure. The lyophilized concentrated crude extract was used for the study.[8]

Induction of Renal Failure: Subtotal Nephrectomy

Subtotal nephrectomy (5/6 nephrectomy) was performed in order to induce chronic renal failure (CRF).[9] Rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of a mixture of ketamine (60 mg/kg, i.p) and xylazine (6.5 mg/kg, i.p.) and a dorsoventral incision parallel to spinal cord was made to expose the left kidney which was then freed of connective tissue. A silk thread was passed from just above renal artery and another from below ureter at kidney and knot was tightened to cut out the upper and lower poles of left kidney (2/3 nephrectomy). Cavity was closed by double sutures of muscle and skin using non absorbable surgical suture (Ethicon® 3-0) once bleeding ceased. One week after the 2/3 nephrectomy, right kidney was exposed and removed (i.e. 5/6 nephrectomy). In each case, post operative care included administration of normal saline (2 ml/animal) to compensate volume loss immediately after surgery, application of Povidone® - Iodine on sutures to prevent infections immediately after surgery, buprenorphine HCl (0.03 mg/kg, s.c) as analgesic, once daily for three days and benzyl penicillin in dose of 20,000 IU/kg, i.m as antibiotic, twice daily (b.i.d), for three days. Animals in Sham group underwent same surgical procedure as above, but kidneys were not removed or cut, but were touched with forceps and threads. Similar post operative care was also given. After surgery, rats were placed individually in cages with free access to food and water.

Grouping of Animals

Animals were randomized according to the body weight and divided in three groups before surgery:

Group I. Normal animals - Control with no nephrectomy

Group II. Animals with 5/6 nephrectomy; and

Group III. Animals with sham surgery.

Estimation of Parameters for Model Standardization

Blood samples were collected from animals of group I, group II as well as group III before and after 8 and 12 weeks of surgery from sublingual vein. Rats were anesthetized using isoflurane as inhalational anesthetic. For biochemical parameters, heparin was used as anticoagulant and then plasma was separated by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma was collected in properly labeled polypropylene tubes and was used for estimation of biochemical parameters like urea and creatinine. Just before and after 8 and 12 weeks of surgery, 2 ml urine sample was collected from all the three groups for analysis of creatinine. Plasma and urinary creatinine was measured using kinetic colour test (Jaffe method; Olympus AU400®).

Plasma urea was determined using kinetic UV test as a standard technique. Renal superoxide dismutase (SOD) (U mg-1 protein) activity was measured in 5/6 nephrectomized saline (1 ml/kg) treated group as well as A. squamosa aqueous extract treated group using the SOD kit (RandD Systems, Inc. [New Delhi, India]) by using renal tissue homogenate and measuring the absorbance at 550 nm.

Assessment of Renoprotective Activity of Water Extract

Initial testing was carried out with three different doses (100-300 mg/kg bw) of the leaf extract in 5/6 nephrectomized male rats. Four groups of six rats each were used in the experiment (group-1 untreated control;

group-II, 100 mg/kg bw;

group-III, 200 mg/kg bw; and

group-IV, 300 mg/kg bw).

The dose of 300 mg/kg bw was found to be the effective dose. Thus, group IV was considered for the study and animals in this group were treated with a single dose 300 mg/kg bw once daily for 10 days.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. The value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All the statistical calculations were performed using the Prism software package (GraphPad Prism, version 5) using unpaired or paired t-test depending on the type of competition.

Results

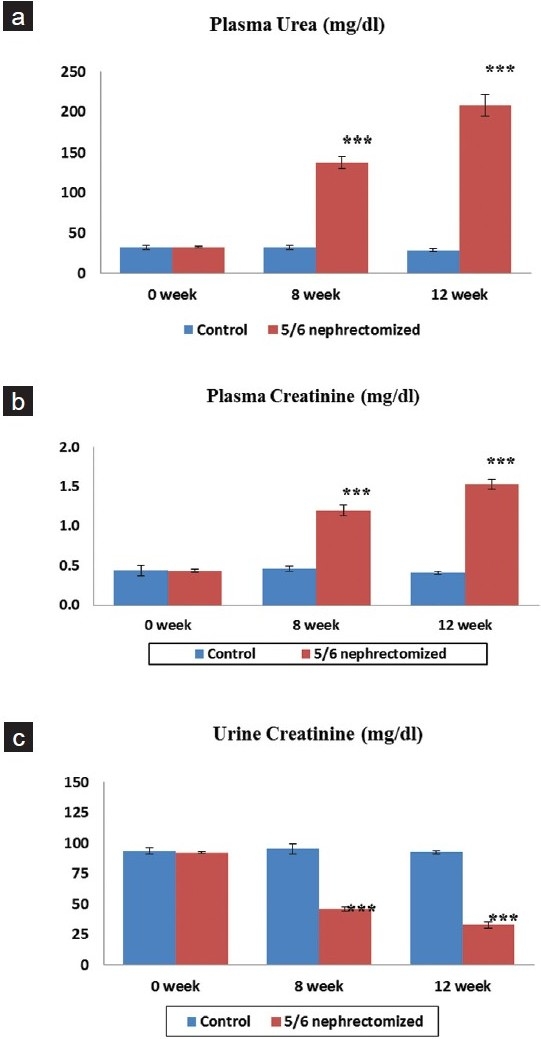

The 5/6 nephrectomy induced moderate to severe CRF in rats in a period of 12 weeks. A significant difference was found in the biochemical as well as urinary parameters between the groups I and II. Animals with 5/6 nephrectomy showed a significant and stable rise in plasma urea and creatinine levels [Figures 1a and 1b] as well as a fall in urine creatinine levels that matched with the rise in plasma creatinine levels [Figure 1c]. No difference was observed between the groups I and III (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of 5/6 nephrectomy on biochemical parameters in control and 5/6 nephrectomized rats. a: Plasma urea (mg/dl) b: Plasma creatinine (mg/dl) c: Urine creatinine (mg/dl). Each value is expressed as mean ± S.E.M (n= 6)

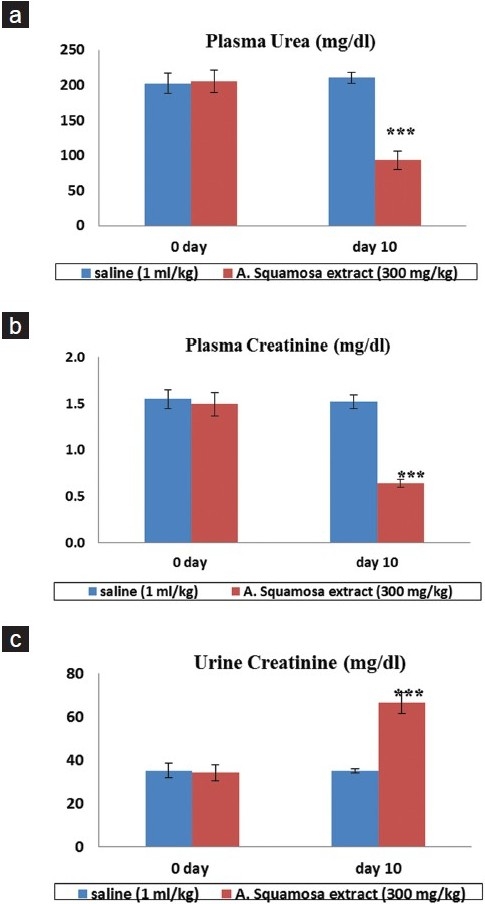

Treatment with A. squamosa was started after completion of 12 weeks in a dose of 300 mg/kg bw once a day for 10 days. At the end of this period, the biochemical and urinary parameters were assessed. There was a significant fall in the plasma urea level that was close to the normal values [Figure 2a]. High plasma creatinine value also decreased with a corresponding rise in the urine creatinine [Figures 2b and 2c, respectively]. Thus, the biochemical parameters which mark the renal failure became near normal following treatment with A. squamosa aqueous extract.

Figure 2.

Effect of aqueous extract of Annona squamosa on biochemical parameters in 5/6 nephrectomized rats Vs. saline (1 ml/kg) treated group. a: Plasma urea (mg/dl) b: Plasma creatinine (mg/dl) c: Urine creatinine (mg/dl). Each value is expressed as mean ± S.E.M (n = 6)

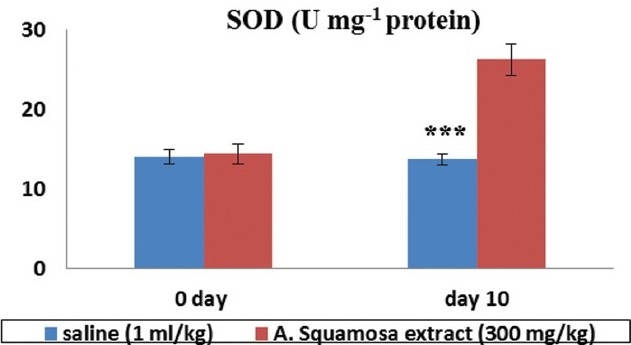

Renal SOD activity [Figure 3] was considerably higher in aqueous extract treated group than its counterpart in saline treated kidneys.

Figure 3.

Effect of aqueous extract of Annona squamosa on renal superoxide dismutase (U mg-1 protein) activity in 5/6 nephrectomized rats Vs. saline (1 ml/kg) treated group. Each value is expressed as mean ± S.E.M (n = 3)

Discussion

Oxidative stress describes a series of reactions involving the chemistry of a wide spectrum of compounds which include free radicals and other reactive molecules that potentially affect the integrity of virtually all the biomolecules.[10] Severe and prolonged oxidative stress can cause subsequent cell injury and death. Superoxide radical and its reduction products like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroxyl radical (OH-) can produce cellular injury through lipid peroxidation of mitochondrial, lysosomal, and plasma membranes, which in turn alters the membrane structure and thus the functional aspects of cells.[11] A role for participation of oxygen free radicals in injury following hypoxic insult has been demonstrated in the brain, heart, and intestine of experimental animals,[12,13] but studies in the kidney are lacking. Protection against free radicals can be achieved by preventing their formation, by blocking the chain reactions, or by repairing the oxidatively damaged biomolecules.[10]

On the other hand, 5/6 nephrectomy (5/6 Nx) has been widely used for induction of experimental CRF and its associated complications.[14] The technique is based on removal of nearly 70% of renal mass at the interval of seven days. This study demonstrated that the technique resulted in renal failure as was evident from the urinary as well as biochemical parameters (increased plasma urea and creatinine and decreased urine creatinine). Thus, at the end of 12th week, a significant decrease in urine creatinine with a subsequent increase in plasma creatinine levels which indicates post compensatory phase of renal failure. A study has shown that A. squamosa extract lowers the plasma urea, uric acid, and creatinine levels by enhancing the renal function impaired in diabetic rats.[15] Our study has demonstrated that the effect of aqueous extract of A. squamosa in amelioration of renal failure is by the virtue of its effect on SOD activity..

There are multiple evidences to suggest the role of oxygen free radicals in renal ischemia and renal failure. SOD is an important antioxidant enzyme which may be used for the free radical destruction and may be inhibited by the free radical species.[16]

We hypothesize that aqueous extract of A. squamous may cause the attenuation of ROS generation through its effect on superoxide dismutase (SOD) in renal cells. This study also provides an indication to further investigate the anti-oxidative effects of A. squamosa species for alleviating chronic renal failure.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Nishiyama A, Yoshizumi M, Hitomi H, Kagami S, Kondo S, Miyatake A, et al. The SOD mimetic tempol ameliorates glomerular injury and reduces MAPK activity in Dahl salt sensitive rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:306–15. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000108523.02100.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wihearls CG. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. Chronic Renal Failure; pp. 2302–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nath KA, Salahudeen AK. Induction of renal growth and injury in the intact rat kidney by dietary deficiency and antioxidants. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1179–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI114824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuroda M, Asaka S, Tofuku Y, Takeda R. Serum antioxidant activity in uremic patients. Nephron. 1985;41:293–8. doi: 10.1159/000183600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandkarni AK. Indian Materia Medica. 116. Vol. 1. Mumbai, India: Popular Prakashan Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirwaikar A, Rajendran K, Kumar CD. In vitro antioxidant studies of Annona squamosa Linn leaves. Indian J Exp Biol. 2004;42:803–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neugarten J. Gender and the progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2807–9. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000035846.89753.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta RK, Kesari AN, Watal G, Murthy PS, Chandra R, Maithal K, et al. Hypoglycaemic and antidiabetic effect of aqueous extract of leaves of Annona squamosa (L.) in experimental animal. Curr Sci. 2005;88:1244–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn S, Kuemmerle NB, Chan W, Hisano S, Saborio P, Krieg RJ, Jr, et al. Glomerulosclerosis in the remnant kidney rat is modulated by dietary á-tocopherol. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2089–95. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 140–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fridovich I. The biology of oxygen radicals. Science. 1978;201:875–80. doi: 10.1126/science.210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogure K, Watson BD, Busto R, Abe K. Potentiation of lipid peroxides by ischemia in rat brain. Neurochem Res. 1982;7:437–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00965496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarnieri C, Flamigni F, Caldarera CM. Role of oxygen in the cellular damage induced by re-oxygenation of hypoxic heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980;12:797–808. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park MS, Song KI, Chung MK, Suh KH, Lee HB. The Effect of rhEPO on Anemia in 5/6 Nephrectomized Rats. Korean J Nephrol. 1997;16:42–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaleem M, Medha P, Ahmed QU, Asif M, Bano B. Beneficial effects of Annona squamosa extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:800–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.William GK, Juneja V. Medical nutrition therapy for renal disorder. In: Mahan KL, Stump ES, editors. Krause's Food and Nutrition Therapy. 12th ed. Toronto: Elsevier Canada; 2008. pp. 921–48. [Google Scholar]