Abstract

Objective

Plasma high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels are inversely correlated with the risk of developing coronary heart disease. Hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) affects plasma HDL cholesterol levels, with estrogen increasing HDL cholesterol levels and progestins blunting this effect. This study was designed to assess the mechanism responsible for these effects.

Materials and Methods

HDL apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) kinetics were studied in 8 healthy postmenopausal women participating in a double-blind, randomized, crossover study comprising 3 phases: placebo, conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) (0.625 mg/d), and CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) (2.5 mg/d). Compared with placebo, treatment with CEE resulted in an increase in apoA-I pool size (+20%, P<0.01) because of a significant increase in apoA-I production rate (+47%, P<0.05) and no significant changes in apoA-I fractional catabolic rate. Compared with the CEE alone phase, treatment with the CEE plus MPA resulted in an 8% (P<0.02) reduction in apoA-I pool size and a significant reduction in apoA-I production rate (−13%, P<0.04), without changes in apoA-I fractional catabolic rate.

Conclusion

Postmenopausal estrogen replacement increases apoA-I levels and production rate. When progestin is added to estrogen, it opposes these effects by reducing the production of apoA-I.

Keywords: apolipoprotein A-I, estrogen, progestin, kinetics stable isotopes

High-density lipoproteins (HDLs) play an important role in the prevention of atherosclerotic plaque development through their key involvement in the reverse cholesterol transport pathway.1,2 By interacting with specialized trans-membrane receptors expressed in peripheral (ATP binding cassette A1, or ABCA1) and hepatic (scavenger receptor class B type 1, or SR-B1) cells, HDL and apolipoprotein (apo) A-I, the major protein component of HDL, mediate the removal and excretion of excess cholesterol, thus reducing the lipid load in the vascular wall.3,4

It is well-documented that postmenopausal hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) is associated with changes in plasma HDL cholesterol levels: an increase in plasma HDL cholesterol levels is characteristically observed during replacement with estrogen only,5–8 whereas the estrogen-progestin combination in HRT results in the blunting or abolishment of the effect of estrogen on HDL cholesterol levels.5,7,8 Most, but not all, studies which have assessed the mechanism by which estrogen replacement increases HDL cholesterol levels have shown an increase in the production rate of apoA-I, with nonsignificant effects on the apoA-I catabolic rate.9–11 Despite the relevant clinical use of progestins in HRT, no studies examining the effect of progestins on HDL metabolism are currently available. The study of the mechanism mediating the changes in HDL cholesterol levels in HRT is important because: (1) it may help understand how HDL and the reverse cholesterol transport pathway are affected and (2) several recent randomized intervention HRT trials have clearly shown no protection from coronary heart disease (CHD) when the combination of estrogen plus progestin is used.12–16

Methods

Subjects

Eight postmenopausal, healthy women [mean age (±SD) 56.4±6.6 years and mean body mass index 28.37±6.30 kg/m2] were enrolled in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study of the effect of 2 formulations of HRT on the kinetic parameters of apoA-I in HDL. Each subject was assigned to a randomized sequence of three treatment phases which included: placebo, estrogen (conjugated equine estrogen [CEE] as Premarin, 0.625 mg per day; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), and estrogen plus progestin (CEE+medroxypro-gesterone acetate [MPA] as Premarin, 0.625 mg per day and Provera, 2.5 mg per day; Pharmacia Upjohn). Each treatment phase lasted 8 weeks and phases were separated by a 4-week washout period. Postmenopausal status was defined as the absence of menstrual cycles for >1 year. Postmenopausal women with coronary heart disease, liver or kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, or with a history of clotting disorders, thromboembolism, and cancer of the breast, uterus, or cervix were not enrolled into the study. Also, women who were smoking, consuming >2 alcoholic drinks per week, or taking medications known to affect plasma lipid metabolism were not enrolled into the study. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tufts University-New England Medical Center. Study candidates provided written informed consent.

Experimental Protocol

Subjects were asked to maintain the same lifestyle, including diet and level of physical activity, throughout the study. On weeks 7 and 8 of each study phase, a blood sample was obtained after 12-hour fasting for the determination of plasma lipid and apolipoprotein levels. Plasma was separated at 1000g for 30 minutes at 4°C and stored at −70°C until analyzed.

On week 8 of each phase, subjects underwent a 15 hour primed constant infusion with deuterated leucine, as previously described.17 Briefly, after a 12-hour overnight fast, starting at 6:00 AM, subjects were fed hourly for 20 hours with small identical meals. Five hours after their first meal, subjects received an intravenous bolus of 10 μmol/kg body weight of deuterated leucine (5,5,5-2H3-L-leucine; C/D/N Isotopes Inc, Point-Claire, Quebec, Canada), immediately followed by a constant infusion with 10 μmol/kg body weight per hour of deuterated leucine for 15 hours. Blood samples were collected into tubes containing EDTA (0.15%) just before the infusion (time 0), and at the following times during the infusion: 30 minutes, 35 minutes, 45 minutes, and 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 14, and 15 hours.

Plasma Lipid Measurements

Fasting plasma total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) levels were measured by automated enzymatic assays.18 Direct low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was measured with reagents from Equal Diagnostics (Exton, Pa). HDL cholesterol was measured directly with a kit from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, Ind). HDL3 cholesterol concentrations were measured by a modification of the classic dextran sulfate-magnesium chloride precipitation protocol19 and HDL2 cholesterol was calculated as the difference between HDL cholesterol and HDL3 cholesterol.19

ApoA-I concentrations were measured in plasma samples obtained during fasting and during the infusion by an immunoturbidimetric assay (Wako, Richmond, Va), as previously described.20

Quantification of HDL particles containing only apoA-I (LpAI) was performed in plasma by an electroimmunodiffusion (rocket) technique (Hydragel LpAI, Sebia, France).21

Isotopic Enrichment and ApoA-I Kinetic Analysis

Five mL of plasma from each infusion time-point were subjected to sequential ultracentrifugation in a Beckman (Palo Alto, Calif) ultracentrifuge, as previously described.22 ApoB-100 in very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and apoA-I in HDL were isolated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, hydrolyzed in 12 N HCl, and amino acids converted to the n-propyl ester heptafluorobutyramide derivative for gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis using an Agilent 5973 instrument, as previously described.17,23–25

Tracer/tracee ratios (%) were calculated as previously described.26 The Simulation Analysis and Modeling II (SAAM II) program (Seattle, Wash) was used to calculate the HDL apoA-I fractional catabolic rates (FCR) using a multicompartmental model, as previously described.27,28 The VLDL apoB-100 leucine enrichment plateau was determined using a monoexponential equation, also using SAAM II, and was used as a measure of the amino acid precursor pool.25,29 Under the assumption of a steady-state with respect to apoA-I, the FCR is considered equivalent to the fractional synthetic rate. ApoA-I production rate (PR) was determined by the following formula:

Plasma volume was estimated as 4.5% of body weight.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed with the SPSS statistical package version 12 (SPSS, Chicago, Ill). Variables were analyzed for distribution and a logarithmic transformation was applied to skewed variables. Statistically significant differences in mean values between phases were assessed by paired Student t tests. Simple correlation analyses were performed with the Pearson correlation coefficient method. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Compared with placebo, treatment with estrogen alone or with the estrogen and progestin combination resulted in nonsignificant reductions in plasma total and LDL cholesterol levels (Table 1). A significant increase in plasma HDL cholesterol levels, caused predominantly by an increase in the HDL2 fraction, was observed during the CEE phase, compared with placebo. Plasma HDL cholesterol levels were significantly lower during the combination treatment than during the CEE treatment, but not significantly different from levels during the placebo phase. Relative to placebo, plasma apoA-I levels were significantly increased by CEE treatment and this effect was accompanied by a significant increase in the LpAI fraction (Table 1). The addition of MPA to CEE resulted in a significant lowering in plasma apoA-I levels and LpAI levels, compared with CEE. However, the CEE+MPA treatment resulted in an increase in apoA-I levels compared with placebo, but this increase was confined to the LpAI:AII subpopulation only.

TABLE 1.

Plasma Levels of Lipids, Lipoproteins, and HDL Subfractions at the End of the Placebo, Estrogen, and Estrogen Plus Progestin Treatments in 8 Postmenopausal Women

| Placebo | CEE | CEE+MPA | % Change CEE vs Placebo | % Change CEE+MPA vs Placebo | % Change CEE+MPA vs CEE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC, mmol/L | 6.20±0.93 | 5.53±0.67 | 5.27±0.67 | −9±17 | −13±16 | −5±6 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.64±0.81 | 1.78±1.00 | 1.58±0.54 | +16±41 | +12±50 | +2±46 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 3.54±0.93 | 2.95±0.78 | 2.87±0.80 | −14±20 | −17±21 | −2±9 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.50±0.52 | 1.66±0.49* | 1.55±0.52‡ | +13±11 | +6±13 | −6±6 |

| HDL2-C, mmol/L | 0.52±0.39 | 0.66±0.34† | 0.54±0.36 | +37±43 | +21±44 | −13±16 |

| HDL3-C, mmol/L | 0.96±0.21 | 1.00±0.16 | 1.00±1.26 | +7±17 | +6±23 | −1±13 |

| ApoA-I, g/L | 1.40±0.24 | 1.61±0.23* | 1.50±0.25†‡ | +19±16 | +10±14 | −7±6 |

| LpAI, g/L | 0.53±0.15 | 0.65±0.20* | 0.55±0.17‡ | +26±19 | +6±15 | −18±16 |

| LpAI:AII, g/L | 0.88±0.11 | 0.96±0.10 | 0.95±0.10† | +10±12 | +9±8 | 0±11 |

Data are presented as mean±SD

Significantly different from placebo:

P<0.02,

P<0.05.

Significantly different from CEE:

P<0.05.

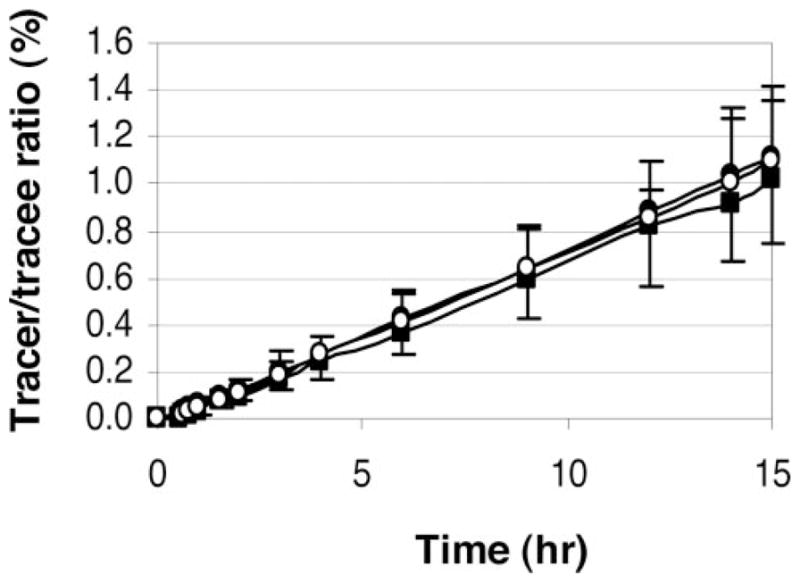

ApoA-I kinetic studies were performed in all subjects at the end of each treatment phase. Subject 7 did not complete the kinetic study during the placebo phase, but completed the CEE and CEE+MPA kinetic studies. Therefore, analyses of apoA-I kinetics are shown only for 7 subjects, unless otherwise specified. A similar rate of deuterated leucine incorporation into apoA-I was observed during all 3 phases (Figure 1). Compared with placebo, the CEE treatment significantly increased the apoA-I pool size (+20%, P=0.01), and this effect was accompanied by a significant increase in apoA-I PR (+47%, P<0.05), partly offset by a nonsignificant increase in apoA-I FCR (+20%, P=0.142) (Table 2). Compared with placebo, the estrogen plus progestin treatment caused a modest elevation in apoA-I pool size (+9%, P<0.04), but no significant changes in the rate of apoA-I production or catabolism.

Figure 1.

Mean (±SD) leucine tracer/tracee ratios in apoA-I during the placebo (black square), CEE (black circle), and CEE+MPA (white circle) phases.

TABLE 2.

Individual ApoA-I Kinetic Parameters in Participating Subjects at the End of the Placebo, Estrogen, and Estrogen Plus Progestin Treatment Phases

| Subject | Pool Size, mg

|

FCR, pools/d

|

PR, mg/kg per day

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | CEE | CEE+MPA | Placebo | CEE | CEE+MPA | Placebo | CEE | CEE+MPA | |

| 1 | 3077 | 4051 | 3577 | 0.196 | 0.296 | 0.257 | 9.11 | 18.08 | 13.99 |

| 2 | 4768 | 4926 | 4698 | 0.217 | 0.272 | 0.248 | 13.01 | 17.13 | 14.56 |

| 3 | 3909 | 5298 | 4816 | 0.165 | 0.185 | 0.234 | 7.93 | 12.07 | 13.89 |

| 4 | 3695 | 5197 | 4220 | 0.186 | 0.313 | 0.283 | 8.53 | 19.72 | 14.39 |

| 5 | 4563 | 5397 | 4880 | 0.184 | 0.174 | 0.166 | 12.98 | 14.7 | 13.12 |

| 6 | 4345 | 4415 | 4226 | 0.208 | 0.166 | 0.142 | 14.66 | 12.18 | 9.99 |

| 7 | ND | 3442 | 2707 | ND | 0.177 | 0.194 | ND | 11.48 | 10.25 |

| 8 | 5411 | 5945 | 5938 | 0.257 | 0.274 | 0.244 | 14.47 | 17.24 | 15.33 |

| Mean* | 4252 | 5033 | 4622 | 0.202 | 0.240 | 0.225 | 11.52 | 15.87 | 13.61 |

| SD* | 766 | 634 | 736 | 0.029 | 0.063 | 0.051 | 2.90 | 2.96 | 1.73 |

| % Change vs placebo | +20 | +9 | +20 | +13 | +47 | +26 | |||

| P value vs placebo | 0.010 | 0.036 | 0.142 | 0.329 | 0.045 | 0.201 | |||

| % Change, vs CEE | −8 | −5 | −13 | ||||||

| P value, vs CEE | 0.013 | 0.231 | 0.037 | ||||||

ND indicates not determined.

Mean and SD calculated after exclusion of subject 7.

To determine the effect of MPA on apoA-I kinetics in the context of estrogen replacement, the CEE+MPA treatment phase was compared with the CEE phase. The significant reduction in apoA-I pool size that was observed with MPA (−8%, P<0.02) was caused by a significant reduction in apoA-I PR (−13%, P<0.04) (Table 2). No significant difference in apoA-I FCR was observed between these 2 phases. Similar results were obtained when subject 7, who had completed both the CEE and CEE+MPA kinetic studies, was included in the analyses (N=8, apoA-I pool size: −10%, P<0.005; apoA-I FCR: −3%, P=0.328; and apoA-I PR: −12%, P<0.03).

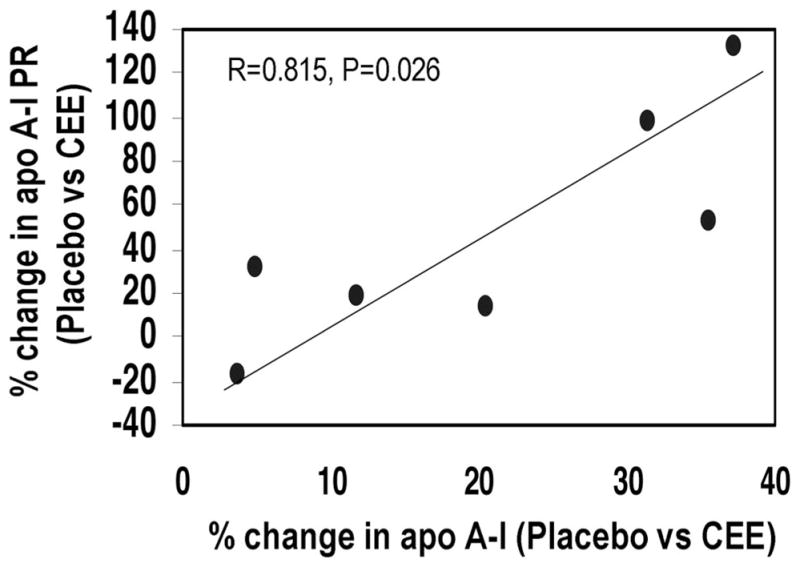

Correlation analyses indicated that the percent change in plasma apoA-I levels between the placebo and the CEE phase was significantly correlated with the percent change in apoA-I PR between these 2 phases (r=0.815, P<0.03) (Figure 2), but not with the percent change in apoA-I FCR (r=0.652, P=0.113). No association of the percent change in apoA-I levels between CEE and CEE+MPA with the percent change in apoA-I PR (r=0.220, P=0.585) or apoA-I FCR (r=−0.265, P=0.526) was observed.

Figure 2.

Association of the percent changes in plasma apoA-I levels with the percent changes in apoA-I production rates between the placebo and the CEE phases.

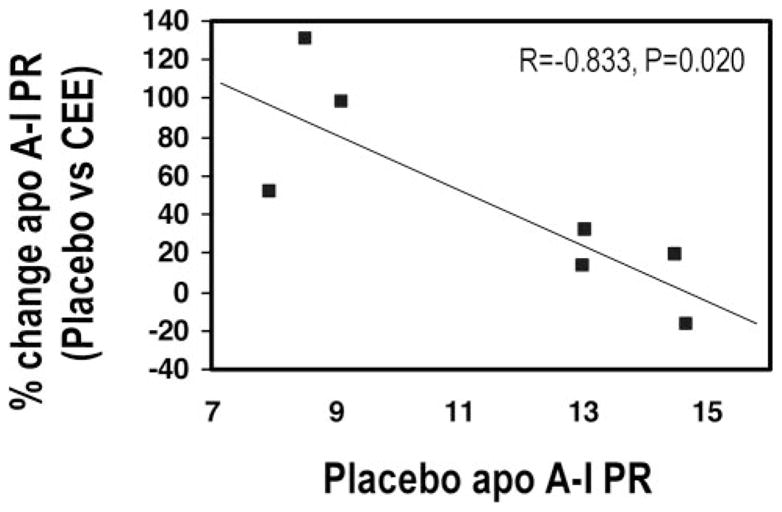

The apoA-I PR during the placebo phase was significantly and inversely correlated with the percent change in apoA-I PR between the placebo and both the CEE (r=−0.833, P=0.02) (Figure 3) and CEE+MPA phases (r=−0.962, P<0.001). Similar associations were observed when the absolute change in apoA-I PR was used (data not shown). No associations were observed for the percent changes in apoA-I FCR.

Figure 3.

Association between placebo apoA-I PR and percent changes in apoA-I PR (placebo vs CEE).

Plasma TG levels were not associated with apoA-I kinetic parameters during the placebo phase. However, during the CEE and CEE+MPA phases, a significant positive association between TG levels and apoA-I FCR was observed (r=0.788, P<0.02 and r=0.763, P<0.03, respectively).

Discussion

An inverse association between plasma levels of HDL cholesterol and the risk of developing CHD has been firmly established by both epidemiologic and intervention studies.30–32 HDL and apoA-I play an important role in the reverse cholesterol transport pathway by actively promoting the efflux of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues and delivering it to the liver for excretion. According to the concept of reverse cholesterol transport, it is conceivable that, by increasing plasma HDL levels through an increase in apoA-I synthesis, a protection from the development of atherosclerotic plaques may occur. Studies in human apoA-I transgenic mice and rabbits support this hypothesis.33,34 In humans, infusions with reconstituted apoA-I liposome complexes have shown an increase in bile acids and neutral steroids in the feces, compatible with the concept of increased excretion of cholesterol.35 Also, estrogen treatment in anovulatory women has been shown to result in increased biliary cholesterol secretion.36

Our study clearly indicates that, in postmenopausal women, treatment with estrogen is associated with an increase in plasma levels of HDL cholesterol and apoA-I caused by an increase in the production of apoA-I. Whether this increase in apoA-I synthesis is beneficial in terms of cardiovascular disease prevention is still unclear. Several placebo-controlled, randomized, clinical intervention trials examining the role of unopposed estrogen on CHD risk have been published; whereas the ERA13 and the WELL-HEART37 studies have failed to show a reduction in coronary atherosclerosis progression with unopposed CEE and 17β-estradiol, respectively, the EPAT study showed significantly lower rate of progression of carotid intima-media thickness in post-menopausal women on 17β-estradiol than in women on placebo.38 Nonsignificant reductions in CHD were observed with estrogen in the ESPRIT study39 and, most recently, in the estrogen-only arm of the Women’s Health Initiative study.40 The results of these clinical trials underscore the need for a clear answer on the effect of unopposed estrogen on CHD risk. However, both primary and secondary prevention randomized clinical trials have clearly indicated that the daily combination of 0.625 mg CEE and 2.5 mg MPA increases the risk of CHD in postmenopausal women.12–16 The combination HRT likely mediates an increase in CHD risk through an increase in inflammation and thrombogenicity, but our study also suggests that the MPA component of HRT has an effect on HDL synthesis and metabolism that may result in increased atherosclerosis.

The increase in apoA-I levels and PR with unopposed estrogen treatment observed in our study is in agreement with the results of three previous studies (Table 3). Schaefer et al41 have shown increased HDL protein synthesis in 4 premenopausal women after administration of ethinyl estradiol. Walsh et al10 have shown in 8 postmenopausal women that the estrogen-related increase in apoA-I PR is mostly confined to the HDL2 fraction (Table 3). Similarly, Brinton11 has demonstrated that the HDL fraction containing only apoA-I (LpAI) is significantly increased during estrogen treatment caused by increased apoA-I PR in this fraction (Table 3). Modest and nonsignificant increases in apoA-I FCR were noted in the latter 2 studies and in the current study. Our results, together with those of these three previous clinical studies, are supported by in vitro experiments showing that hepatic cells grown in the presence of estradiol express apoA-I at significantly higher levels than control cells, because of an activation of the transcription of the apoA-I gene.42,43 A reduction in apoA-I FCR with estrogen treatment was instead observed by Hazzard et al44 in 1 postmenopausal woman with hyperalphalipoproteinemia. Similarly, Quintao et al9 showed a significant reduction in apoA-I FRC in 7 postmenopausal women after a 4-month treatment with estradiol, but these results could have been affected by the prolonged storage of the autologous 125I-labeled HDL injected in the estrogen phase. Therefore, the discrepancy in results between these two latter studies and the previous studies may be attributed to sample preparation, individual variation in response to estrogen treatment, or to alterations in HDL particle during the process of radioiodination, which may lead to abnormal HDL clearance.45

TABLE 3.

Previous Studies of Hormonal Treatment and apoA-I Kinetics

| Reference | Subjects | Treatment | Fraction | ApoA-I* | ApoA-I FCR† | ApoA-I PR‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schaefer et al41 | Pre-mp, N=4 | Ethinyl estradiol | HDL | +24%§ | −3% | +17%§ |

| Hazzard et al44 | Post-mp, N=1 | Ethinyl estradiol | HDL | +29% | −42% | −37% |

| Quintao et al9 | Post-mp, N=7 | 17β-estradiol | HDL | +16%§ | −45%§ | |

| Walsh et al10 | Post-mp, N=8 | 17β-estradiol | HDL2 | +37%§ | +3% | +36%§ |

| HDL3 | +12%§ | +10% | +19%§ | |||

| Walsh et al10 | Post-mp, N=8 | 17β-estradiol, transdermal | HDL2 | +3% | +8% | +7% |

| HDL3 | −7% | +14% | +4% | |||

| Brinton11 | Post-mp, N=6 | Ethinyl estradiol | LpAI | +66%§ | +7% | +76%§ |

| LpAIAII | +14% | +5% | +22% | |||

| Haffner et al46 | Post-mp, N=4 | Stanozolol | HDL | −55%§ | +62% | −35% |

| Current study | Post-mp, N=7 | CEE (vs placebo) | HDL | +20%§ | +20% | +47%§ |

| N=8 | MPA+CEE (vs CEE) | HDL | −8%§ | −5% | −13%§ | |

| N=7 | MPA+CEE (vs placebo) | HDL | +9% | +13% | +26% |

Post-mp indicates postmenopause; Pre-mp, premenopause.

Percent change in plasma apo A-I concentration from control phase (placebo or baseline), unless otherwise specified.

Percent change in apoA-I FCR from control phase (placebo or baseline), unless otherwise specified.

Percent change in apoA-I PR from control phase (placebo or baseline), unless otherwise specified.

Statistically significant, P<0.05.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to identify the mechanism for the reduction in HDL cholesterol levels associated with the use of a progestin in HRT. To date, 1 study has examined the effect of stanozolol, an anabolic androgenic steroid, on apoA-I metabolism. When stanozolol was administered to four postmenopausal women, a significant effect was shown on apoA-I mass (−55%, P<0.04), with a trend toward both a reduction in PR (−35%, P=0.07) and an increase in FCR (+62%, P=0.08).46 Therefore, it may be hypothesized that androgenic property of MPA is responsible for the observed reduction in apoA-I PR.

Even though this and other studies have documented an effect of estrogen on apoA-I metabolism, the overall effect of estrogen or progestin on the reverse cholesterol transport pathway in humans is not known. In rodents, estrogen treatment causes significant increases in hepatic mRNA levels for ABCA147 and significant reductions in hepatic SR-BI expression.48 No information is available on the effect of HRT components on ABCA1 and SR-BI in vascular cells.

In our study, the increase in apoA-I PR during HRT, expressed as both percent and absolute change, was inversely associated with the apoA-I PR measured during the placebo phase. This may suggest a greater response in subjects with lower HDL cholesterol levels. However, the clinical significance and the nature of this association remain to be established.

HRT is known to increase plasma TG levels. A nonsignificant increase in plasma TG levels during the CEE and CEE+MPA phases (+16% and +12%, respectively) was observed in subjects participating in our study. The significant association between plasma TG levels and apoA-I FCR during the CEE and CEE+MPA phases is probably explained by transfer of TG molecules to HDL, with subsequent increased susceptibility of HDL to catabolism.49 Therefore, the estrogen-related increase in plasma TG levels may contribute to the observed trend toward an increased apoA-I FCR during estrogen treatment. In contrast with our study, a decrease in plasma TG levels during HRT treatment with CEE and micronized progesterone has been observed by Wolfe et al.50

The relatively small sample size of our study is a limitation shared by the great majority of previously published apo A-I kinetic studies45 and may have been associated with a type II error, thereby reducing our ability to detect smaller differences than those detected. A larger sample size may have enabled us to detect a statistically significant effect of estrogen treatment on apoA-I FCR, possibly mediated by the increase in TG levels.

Our study clearly indicates that the increase in apoA-I levels after replacement with estrogen alone is caused by an increase in apoA-I production and that the addition of a progestin counteracts the estrogen-mediated increase in apoA-I levels and production rate.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NHLBI grant K08 HL03209 to S.L.-F., and by the US Department of Agriculture Research Service under agreement No. 58-1950-4-401. Support was also provided by grant M01 RR00054 to the New England Medical Center General Clinical Research Center, funded by the National Center for the Research Resources of the NIH. Partial support for subject recruitment was provided from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center grant AG08812. Dr Barrett is a Fellow of the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia and is partially supported by NIH/NIBIB grant P41 EB-001975.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest is reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Glomset J. The plasma lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase reaction. J Lipid Res. 1968;9:155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fielding CJ, Fielding PE. Molecular physiology of reverse cholesterol transport. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:211–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oram J, Vaughan A. ABCA1-mediated transport of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids to HDL apolipoproteins. Curr Opinion Lipid. 2000;11:253–260. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschule T, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–520. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The writing group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh K, Mincemoyer R, Bui M, Csako G, Pucino F, Guetta V, Waclawiw M, Cannon RI. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on fibrinolysis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:683–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703063361002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson M, Maki K, Marx P, Maki A, Cyrowski M, Nanavati N, Arce J. Effects of continuous estrogen and estrogen-progestin replacement on cardiovascular risk markers in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3315–3325. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamon-Fava S, Postfai B, Asztalos BF, Horvath KV, Dallal G, Schaefer EJ. Effects of estrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate on subpopulations of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and high-density lipoproteins. Metabolism. 2004;52:1330–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(03)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintao E, Nakandakare E, Oliveira HCF, Rocha J, Garcia RC, de Melo N. Oral estradiol-17beta raises the level of plasma high-density lipoprotein in menopausal women by slowing down its clearance rate. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1991;125:657–661. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1250657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh BW, Li H, Sacks FM. Effects of postmenopausal hormone replacement with oral and transdermal estrogen on high density lipoprotein metabolism. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:2083–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinton EA. Oral estrogen replacement therapy in postmenopausal women selectively raises levels and production rates of lipoprotein AI and lowers hepatic lipase activity without lowering the catabolic rate. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:431–440. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulley SB, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg CD, Herrington DM, Riggs B, Vittinghoff E for the Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Brosnihan B, Sharp PC, Shumaker SA, Snyder TE, Furberg CD, Kowalchuk GJ, Stuckey TD, Rogers WJ, Givens DH, Waters D. Effects of estrogen replacement on the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:522–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke S, Kelleher J, Lloyd-Jones H, Slack M, Schfiel P. A study of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with ischemic heart disease: the Papworth HRT atherosclerosis study. British J Obst Gyn. 2002;109:1056–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angerer P, Stork S, Kothny W, Schmitt P, von Schacky C. Effects of oral postmenopausal hormone replacement on progression of atherosclerosis. A randomized, controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:262–268. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohn J, Wagner D, Cohn S, Millar J, Schaefer EJ. Measurement of very low density and low density lipoprotein apolipoprotein (apo) B-100 and high density lipoprotein apoA-I production in human subjects using deuterated leucine. Effects of fasting and feeding. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:804–811. doi: 10.1172/JCI114507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNamara JR, Schaefer EJ. Automated enzymatic standardized lipid analyses for plasma lipoprotein fractions. Clin Chim Acta. 1987;166:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(87)90188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Quantitation of high density lipoprotein subclasses after separation by dextran sulfate and Mg2+ precipitation. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contois J, McNamara J, Lammi-Keefe C, Wilson P, Massov T, Schaefer E. Reference intervals for plasma apolipoprotein A-I determined with a standardized commercial immunoturbidimetric assay: results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Clin Chem. 1996;42:507–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fruchart JC, Ailhaud G. Apolipoprotein A-containing lipoprotein particles: physiological role, quantification and clinical significance. Clin Chem. 1992;38:793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havel RJ, Eder H, Bragdon J. The distribution and chemical composition of ultracentrifugally separated lipoprotein in human serum. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:1345–1363. doi: 10.1172/JCI103182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velez-Carrasco W, Lichtenstein AH, Welty FK, Li Z, Lamon-Fava S, Dolnikowski GG, Schaefer EJ. Dietary restriction of saturated fat and cholesterol decreases HDL apoA-I secretion. Arter Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:918–924. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtenstein AH, Hachey D, Millar J, Jenner JL, Booth L, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Measurement of human apolipoprotein B-48 and B-100 kinetics in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins using [5,5,5–2H3]leucine. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:907–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welty F, Lichtenstein AH, Barrett P, Dolnikowski GG, Schaefer EJ. Human apolipoprotein (apo) B-48 and apo B-100 kinetics with stable isotopes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2966–2974. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobelli C, Toffolo G, Bier D, Nosadini R. Models to interpret kinetic data in stable isotope tracer studies. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:E551–E564. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.253.5.E551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welty F, Lichtenstein AH, Barrett PH, Dolnikowski GG, Schaefer EJ. Interrelationships between human apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoproteins B-48 and B-100 kinetics using stable isotopes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1703–1707. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000137975.14996.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batista M, Welty F, Diffenderfer M, Sarnak M, Schaefer EJ, Lamon-Fava S, Asztalos BF, Dolnikowski GG, Brousseau ME, Marsh J. Apolipoprotein A-I, B-100, and B-48 metabolism in subjects with chronic kidney disease, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2004;53:1255–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millar J, Lichtenstein AH, Cuchel M, Dolnikowski GG, Hachey D, Cohn J, Schaefer EJ. Impact of age on the metabolism of VLDL, IDL, and LDL apolipoprotein B-100 in men. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:1155–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WE, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977;62:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Expert Panel. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins SJ, Collins D, Wittes JT, Papademetriou V, Deedwania PC, Schaefer EJ, McNamara JR, Kashyap ML, Hershman JM, Wexler LF, Rubins EB. Relation of gemfibrozil treatment and lipid levels with major coronary events. VA-HIT: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:1585–1591. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin E, Krauss R, Spangler E, Verstuyft J, Clift S. Inhibition of early atherogenesis in transgenic mice by human apolipoprotien A-I. Nature. 1991;353:265–267. doi: 10.1038/353265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duverger N, Kruth H, Emmanuel F, Caillaud J, Viglietta C, Castro GR, Tailleux A, Fievet C, Fruchart JC, Houdebine L, Denefle P. Inhibition of atherosclerosis development in cholesterol-fed human apolipoprotein A-I-transgenic rabbits. Circulation. 1996;94:713–717. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eriksson M, Carlson LA, Miettinen T, Angelin B. Stimulation of fecal steroid excretion after infusion of recombinant proapolipoprotein A-I. Potential reverse cholesterol transport in humans. Circulation. 1999;100:594–598. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.6.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Everson G, McKinley C, Kern FJ. Mechanisms of gallstone formation in women. Effects of exogenous estrogen (Premarin) and dietary cholesterol on hepatic lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:237–246. doi: 10.1172/JCI114977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Azen SP, Lobo RA, Shoupe D, Mahrer P, Faxon D, Cashin-Hemphill L, et al. Hormone therapy and the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:535–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, Shoupe D, Sevanian A, Mahrer PR, Selzer RH, Liu CR, Liu CH, Azen SP Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial Research Group. Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Inter Med. 2001;135:939–953. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The ESPRIT team. Estrogen therapy for prevention or reinfarction in postmenopausal women: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:2001–2008. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)12001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaefer EJ, Foster DM, Zech LA, Lindgren FT, Brewer HBJ, Levy RI. The effects of estrogen administration on plasma lipoprotein metabolism in premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:262–267. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-2-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin FY, Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Estradiol stimulates apolipoprotein A-I- but not A-II-containing particle synthesis and secretion by stimulating mRNA transcription rate in Hep G2 cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:999–1006. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.6.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamon-Fava S, Micherone D. Regulation of apo A-I gene expression: mechanism of action of estrogen and genistein. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:106–112. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300179-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hazzard WR, Haffner S, Kushwaha R, Applebaum-Bowden D, Foster DM. Preliminary report: kinetic studies on the modulation of high-density lipoprotein, apolipoprotein, and subfraction metabolism by sex steroids in a postmenopausal woman. Metabolism. 1984;33:779–784. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marsh J, Welty FK, Schaefer EJ. Stable isotope turnover of apolipoproteins of high-density lipoproteins in humans. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:261–266. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haffner S, Kushwaha R, Foster DM, Applebaum-Bowden D, Hazzard WR. Studies on the metabolic mechanism of reduced high-density lipoproteins during anabolic steroid therapy. Metabolism. 1983;32:413–420. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava RA. Estrogen-induced regulation of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) in mice: a possible mechanism of atheroprotection by estrogen. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;240:67–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1020604610873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landschulz KT, Pathak RK, Rigotti AKM, Hobbs HH. Regulation of scavenger receptor, class B, type 1, a high density lipoprotein receptor, in liver and steroidogenic tissues of the rat. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:984–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI118883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamarche B, Uffelman K, Carpentier A, Cohn J, Steiner G, Barrett P, Lewis G. Triglyceride enrichment of HDL enhances in vivo metabolic clearance of HDL apo A-I in healthy men. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1191–1199. doi: 10.1172/JCI5286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolfe B, Barrett P, Laurier L, Huff M. Effects of continuous conjugated estrogen and micronized progesterone therapy upon lipoprotein metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:368 –375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]