Abstract

PTH stimulates bone formation and increases hematopoietic stem cells through mechanisms as yet uncertain. The purpose of this study was to identify mechanisms by which PTH links actions on cells of hematopoietic origin with osteoblast-mediated bone formation. C57B6 mice (10 d) were nonlethally irradiated and then administered PTH for 5–20 d. Irradiation reduced bone marrow cellularity with retention of cells lining trabeculae. PTH anabolic activity was greater in irradiated vs. nonirradiated mice, which could not be accounted for by altered osteoblasts directly or osteoclasts but instead via an altered bone marrow microenvironment. Irradiation increased fibroblast growth factor 2, TGFβ, and IL-6 mRNA levels in the bone marrow in vivo. Irradiation decreased B220 cell numbers, whereas the percent of Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ (LSK), CD11b+, CD68+, CD41+, Lin−CD29+Sca-1+ cells, and proliferating CD45−Nestin+ cells was increased. Megakaryocyte numbers were reduced with irradiation and located more closely to trabecular surfaces with irradiation and PTH. Bone marrow TGFβ was increased in irradiated PTH-treated mice, and inhibition of TGFβ blocked the PTH augmentation of bone in irradiated mice. In conclusion, irradiation created a permissive environment for anabolic actions of PTH that was TGFβ dependent but osteoclast independent and suggests that a nonosteoclast source of TGFβ drives mesenchymal stem cell recruitment to support PTH anabolic actions.

PTH is a multifaceted hormone vital and central to bone homeostasis, development, and repair. PTH is currently the only anabolic agent in clinical use in the United States for the treatment of osteoporosis, hence having bone building properties. PTH is also under intense investigation for its use in the treatment of localized osseous defects, such as fractures and craniofacial defects, and for its potential use as a stem cell therapy (1–4). Despite promising results and intense interest across the field, the precise mechanisms mediating these anabolic actions are still elusive. Several theories have been proposed, including stimulation of osteoprogenitor cell proliferation, inhibition of osteoblast apoptosis, activation of transcriptional mediators, and augmentation of certain growth factors (5–7).

Bone houses the hematopoietic reservoir where circulating blood cells are generated, and evidence is strong for a role of bone cells and their juxtacrine and paracrine interactions in support of hematopoiesis (8). A relatively unexplored area is how hematopoietic cells in the marrow impact bone formation. Interest has focused on the potential role of PTH and PTHrP as stem cell factors that support hematopoiesis through their ability to target osteoblastic cells. Work with a constitutively active PTH/PTHrP receptor (PPR) revealed that PTH signaling resulted in increased bone formation in the trabecular compartment at the same time that cortical bone was reduced (9). Further investigation revealed that PTH was capable of supporting hematopoiesis through its action on early hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) and most recently that IL-6 plays a role in mediating these effects (10, 11). It has become increasingly clear that the anabolic action of PTH is not simply activation of osteoblastic bone forming cells, but likely requires accessory cells in an intricate temporal and spatial organization. A putative role for cells of the osteoclast lineage has been suggested but is still controversial (12–15). PTH has novel actions to expand cells of the HSC niche, which may function in the impact of PTH in bone formation (9). There are multiple approaches that perturb the hematopoietic environment and could impact subsequent bone formation. The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of altering the bone marrow microenvironment via irradiation on PTH anabolic actions in bone.

Materials and Methods

Animal care and experimentation

C57B6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) at postnatal d 10 were irradiated [310–325 centigray (cGy), two fractions, 3 h apart] with a 250-kV orthovoltage unit (Philips Medical Systems, Brookfield, WI). Three temporal approaches included an early time point (3 d after irradiation) to evaluate acute effects, a short-term evaluation of PTH actions (5 d of PTH treatment starting 24 h after irradiation) and a long term evaluation of PTH actions (20 d of PTH treatment starting 24 h after irradiation) (Fig. 1). PTH 1–34 (50 μg/kg) (Bachem, Torrance, CA) was administered daily sc similar to previously published protocols for bone anabolic actions of PTH (13, 16). A selective inhibitor of TGFβ type I receptor (SB-505124; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO) was used in the long-term evaluation of PTH actions and was administered daily ip (30 mg/kg). C57B6 mice were also used for primary cell isolation within 1 wk of birth. Bone marrow was harvested from luciferase expressing mice [C3-Tg(TettTALuc)1Dgs/J; The Jackson Laboratory] 4–8 wk of age and used for in vitro coculture assays. At killing, whole body and spleen weights and femur lengths and widths were recorded. Mice were housed and cared for by the Unit for Laboratory Animal Maintenance, and all animal procedures were performed in compliance with the institutional ethical requirements approved by the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

Fig. 1.

A, Experimental design. Three different protocols were used for the various in vivo aspects of this study, all of which involved irradiation (IRR) (325 cGy twice 3 h apart) or non-IRR control of 10-d-old C57B6 mice. One set of studies (top) killed mice 3 d later and evaluated body and spleen weight, histologic evaluation of bones, flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cell populations, or isolation of calvarial or bone marrow cell populations for in vitro analyses. Another set of studies (middle) administered PTH (1–34) (50 μg/kg) or vehicle control 1 d after irradiation for 5 d followed by evaluation of body and spleen weight, histologic evaluation of bones, flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cell populations, isolation of bone marrow RNA for microarray and quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RT-PCR), or isolation of bone marrow proteins for ELISA. The third set of studies administered PTH (1–34) (50 μg/kg) or vehicle control 1 d after irradiation for 20 d followed by histologic evaluation of bones, flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cell populations, and serum analyses of bone turnover markers. Early effects of irradiation: Mice (10 d) were irradiated (IRR) with 325 cGy twice 3 h apart or not (NON-IRR) and killed 3 d later. B, Body weight, n = 5–7/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. NON-IRR. C, Spleen weight (as a percent of total body weight), n = 5–7/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. NON-IRR, with representative image of spleen from NON-IRR (left) and IRR (right) mouse. D, Representative image of vertebra from an IRR mouse (top) and NON-IRR control mouse (bottom) with expanded inset. Flow cytometric analysis: E, Total cell numbers from one femur and tibia per mouse; F, B220 cells expressed as a percent of the total cell numbers; G, LSK cells expressed as a percent of the total cell numbers with representative FACs plots on right (LSK cells are in upper right quadrant), n = 4–5/group and *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01 vs. NON-IRR for E–G.

Reagents

The antibodies B220 [Ra3-6B2, phycoerythrin (PE)], CD11b (M1/70, allophycocyanin/APC), CD41 [MWReg30, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)], Lin cocktail (APC), Sca-1 (E13-161.7, FITC), c-kit (2B8, PE), Nestin (25/NESTIN, APC), CD45 (30-F11, PE), the Fc blocker, and the FITC bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Flow assay system were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). CD68 (FA-11, Alexa Fluor 647) and the Leucoperm Reagents were obtained from AbD Serotec (Raleigh, NC), and CD29 (eBioHMb1–1, PE) was obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)5b and procollagen type 1 amino-terminal peptide (P1NP) immunoassays were obtained from IDS (Immunodiagnostic Systems Ltd, Fountain Hills, AZ). The osteocalcin (OCN) detection assay was obtained from Biomedical Technologies (Stoughton, MA) and the TGFβ Quantikine ELISA system from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System was from Promega (Madison, WI). Reagents for quantitative PCR gene expression assays were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). All other supplies were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless indicated otherwise.

Flow cytometric analysis

Immediately after killing, bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs and tibiae and 1 × 106 cells incubated with fluorescent-conjugated antibodies (PE 5 μl; FITC 2 μl; APC 5 μl; Fc Blocker 2 μl; lineage cocktail 10 μl; CD68 10 μl) in FACS staining buffer (2% FBS, 1× PBS, and 2 mm EDTA) 15–30 min at 4 C. Cells were washed and resuspended in 7-aminoactinomycin D (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to discriminate live from dead cells. Intracellular stains (CD68) required permeabilization with Leucoperm Reagents before staining. Subsets of mice were injected with BrdU 100 mg/kg 2 h before killing and the manufacturer's BrdU Flow protocol followed. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur and analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Histologic assays

Histomorphometric analyses were performed as previously described (16, 17). Briefly, after fixation and decalcification, paraffin-embedded tibiae and vertebrae were cut (5 μm), stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and bone areas measured using a computer-assisted histomorphometric analyzing system (Image-Pro Plus version 4.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc., Silver Spring, MD). TRAP staining was performed using the Leukocyte Acid Phosphatase Assay (Sigma) following the manufacturer's protocol. A von Willebrand factor (vWF) antibody (NeoMarker, Fremont, CA) was used to stain megakaryocytes and performed using standard indirect immunoperoxidase procedures with the 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole Cell and Tissue staining system (R&D Systems).

Blood and bone marrow “serum” assays

Whole blood was obtained at killing by intracardiac blood draw, serum separated and kept frozen until biochemical assays were performed. The serum TRAP5b, P1NP immunoassays, and OCN detection assays were performed per manufacturer's protocols. Total bone marrow was centrifuged from hindlimb bones into 1× PBS containing a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), and supernatant transferred and frozen until assay for TGFβ according to manufacturer's protocol.

In vitro assays: Proliferation and differentiation

Primary calvarial cells were isolated from untreated mice with sequential collagenase A digestion (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and trypsin in serum-free α-MEM for 10, 20, and 30 min. Cells from the last digestion were expanded, plated in complete medium (50,000/cm2), and at confluence, bone marrow cells from d 3 irradiated or age-matched nonirradiated mice added at 1.5 × 106/well with mineralization media (α-MEM; 5% FBS; 1% penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine; 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid; and 10 mm β-glycerophosphate). A second application of fresh bone marrow from d 5 post irradiated or controls was added 2 d later. Media were refreshed every 2–3 d for 18 d and then von Kossa staining performed (as described below).

Primary calvarial cells from irradiated or nonirradiated mice were isolated as above, plated at equal densities, and mineralized for 21d, at which point von Kossa staining was performed. Briefly, cells were fixed, serially hydrated, and incubated with 5% silver nitrate for 1 h (37 C). After washing, cells were exposed to bright light (30 min), scanned (UMAX scanner), and mineralized area determined using ImagePro 4.0.

Ex vivo and in vitro: Coculture and adipocyte enumeration

Bone marrow cells were flushed from luciferase expressing mice (4–6 wk), expanded, and plated at 15,000/cm2 to assess cell numbers over time. The next day, bone marrow cells from nonluciferase expressing 3 d post irradiated and nonirradiated age-matched mice were flushed, counted, and cocultured with the previously plated luciferase-expressing bone marrow. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System was used per manufacturer's protocol with slight modification. On 0, 2, and 5 d, cells were washed, trypsinized, lysed, and stored at −20 C. After thawing, lysates were combined with luciferin and analyzed on a Monolight 3010 Luminometer (BD Biosciences). Relative light units were used as a reflection of cell numbers.

Bone marrow cells were flushed from long bones of either 3 d after irradiated or age-matched nonirradiated mice and plated at 1.3 × 106/well with fresh media changes every 2–3 d. Adherent cells were counted with trypan blue dye exclusion after 14 d. Primary calvarial cells were isolated (as described above) from either 3 d after irradiated or age-matched nonirradiated mice. Cells were plated at 10,000/cm2 and counted on 2, 5, 7, and 9 d using trypan blue dye exclusion.

Bone marrow cells were flushed from long bones of 3 d after irradiated and age-matched nonirradiated mice and plated at equal densities (1.5 × 106 cells per well). Oil Red O staining was performed 24 h after plating with 0.5% Oil Red O in isopropanol/water. Cells were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 30 min, stained with Oil Red O (1 h), washed, and counted.

Gene expression and microarray analyses

Tibiae were harvested from mice administered PTH or vehicle for 5 d (d 6 after irradiated and age-matched nonirradiated controls) and were flushed with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and total RNA isolated per manufacturer's protocol. Double stranded cDNA was synthesized from RNA (2 μg) using random hexamers and reverse transcribed using Multiscribe reverse transcriptase. TaqMan universal PCR master mix was used with probe/primer sets from Applied Biosystems: IL-6, BMP2, BMP6, CXCL12 [stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)], platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)B, IGF1, fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), TGFβ, and FAM reporter dye (Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Rodent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (VIC reporter dye) was used as an endogenous control. Amplification of cDNA was performed using the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification of data generated using this system was performed using the standard curve method.

Sets of RNA samples were also further purified using the RNEasy system (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) per manufacturer's protocol and processed by the University of Michigan Affymetrix GeneChip Array Core. Briefly, sample integrity was confirmed by capillary electrophoresis resolving 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA on an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Total RNA (50 ng) was run on an Affymetrix GeneChip MouseGene 1.0 ST Array, which includes 28,852 gene-level probe sets constituting 26 probes spanning each gene. Gene expression values were determined using a robust multiarray average (18) and the affy, affyPLM, oligo, and limma packages of bioconductor implemented in the R statistical environment. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (19) indicated at most a 5% false positive. Samples were tested to be “overrepresented” by using a hypergeometric distribution similar to a Fishers exact test.

Statistical analyses

Some in vivo experiments were performed at different times (appropriately controlled at each time) and datasets added together for n values as shown. All in vitro experiments were performed two to three times with similar results, and representative assays are shown. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA or Student's t test (unless otherwise indicated) using the GraphPad InStat statistical program (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) with significance of P < 0.05.

Results

Effects of irradiation: Day 13 postnatal (3 d after irradiation)

Total body irradiation at 10 d of age resulted in reduced body weight compared with nonirradiated controls after 3 d (Fig. 1B). Spleen weight was even more significantly reduced relative to body weight reflecting the impact on immune cells (Fig. 1C). Histologically, the bone marrow of the nonirradiated mice appeared highly cellular in contrast to the irradiated mouse bones, which appeared relatively devoid of cells (Fig. 1D). On close inspection of the trabecular surfaces in nonirradiated mice, cells lining the trabecular surface appeared flattened and quiescent, whereas the irradiated mouse trabecular surfaces appeared densely populated with plump cells giving an appearance of robust activity.

There were significant alterations in the hematopoietic cell profile with reduced total cell numbers in the marrow and a significant reduction in the percentage of B220 cells (Fig. 1, E and F). The hematopoietic progenitor population delineated by the markers LSK (Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+) were numerically reduced (22,000 ± 2100 vs. 5600 ± 1800 cells/one hindlimb) yet significantly increased as a percentage of the total population, reflecting a relative protective effect in these lower cycling activity cells (Fig. 1G).

Effects of irradiation: Day 16 postnatal (6 d after irradiation)

Mice that were irradiated, administered PTH or vehicle for 5 d and then killed 24 h after the last PTH injection, had significantly reduced total numbers of cells per femur and tibia (Table 1). PTH vs. vehicle treatment resulted in a significant (2-fold) increase in total cell numbers in irradiated mice. The number of proliferating cells labeled with BrdU was significantly reduced in irradiated mice, and PTH induced a 2-fold increase in BrdU+ cells, similar to the increase in total cell numbers. The percentage of CD41+ cells, a marker for mature megakaryocytic cells and hematopoietic progenitor cells, was significantly increased with irradiation but was not responsive to PTH treatment. The percentage of CD41+ BrdU+ cells in the marrow was increased in irradiated mice with BrdU positivity formulating a greater portion of the CD41+ cells in irradiated vs. nonirradiated mice (∼60 vs. 40%), demonstrating that after irradiation, cells were stimulated to enter the cell cycle.

Table 1.

Bone marrow cell composition

| Nonirradiated vehicle | Nonirradiated PTH | Irradiated vehicle | Irradiated PTH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 16 (6 d after irradiation)n = 6–7/group | ||||

| Cell no./one femur and tibia per body weight × 106 | 2.00 ± 0.50 | 2.40 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.10e | 0.60 ± 0.04b |

| BrdU+ cells/leg × 106 | 3.60 ± 1.00 | 4.50 ± 0.90 | 0.98 ± 0.20a | 2.10 ± 0.40b |

| CD41+ cells (%) | 11.30 ± 1.50 | 11.10 ± 0.60 | 32.40 ± 4.20a | 37.40 ± 4.30a |

| CD41+ BrdU+ cells (%) | 4.30 ± 0.70 | 4.80 ± 0.30 | 22.90 ± 4.40a | 19.40 ± 1.40a |

| Day 31 (21 d after irradiation)n = 3–5/group | ||||

| Cell no./one femur and tibia per body weight × 106 | 2.82 ± 0.28 | 1.85 ± 0.10c | 1.55 ± 0.34c | 0.83 ± 0.17g |

| B220+ cells (%) | 22.78 ± 1.11 | 23.64 ± 2.52 | 11.06 ± 1.04f | 11.63 ± 1.03f |

| CD41+ cells (%) | 4.41 ± 0.36 | 4.68 ± 0.46 | 3.21 ± 0.35a | 3.16 ± 0.32a |

| LSK cells (%) | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.03d | 0.30 ± 0.05b,g |

P < 0.05 vs. nonirradiated vehicle and nonirradiated PTH.

P < 0.05 vs. irradiated vehicle.

P < 0.05 vs. nonirradiated vehicle.

P < 0.01 vs. nonirradiated.

P < 0.001 vs. nonirradiated vehicle.

P < 0.001 vs. nonirradiated and nonirradiated PTH.

P < 0.05 vs. nonirradiated PTH.

Effects of irradiation: Day 31 postnatal (21 d after irradiation)

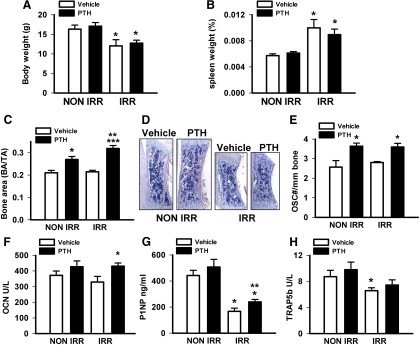

To assess longer-term effects, mice were irradiated and then administered PTH or vehicle for 3 wk, killed, and analyzed for skeletal and hematopoietic profiles. Irradiated mice had significantly lower body weight compared to nonirradiated mice, and PTH did not alter body weight (Fig. 2A). By this time point, spleen weight expressed as a percent of total body weight was significantly increased in irradiated vs. nonirradiated mice with no impact of PTH in either group (Fig. 2B). Total numbers of cells per femur and tibia expressed as a ratio of total body weight were significantly reduced in irradiated vs. nonirradiated mice (Table 1). PTH treatment resulted in significantly reduced numbers of cells in both irradiated and nonirradiated mice. Flow cytometric analysis revealed a significant reduction in the B220 and the CD41 populations in irradiated vs. nonirradiated mouse bone marrow. The LSK population was decreased in the irradiated vs. the nonirradiated controls (5-fold reduction in absolute numbers). PTH did not alter the B cell or the megakaryocyte population but tended to increase the percentage of LSK cells in the nonirradiated population and significantly increased LSK cells in the irradiated mice.

Fig. 2.

Mice (10 d) were irradiated (IRR) or not (NON IRR) with 325 cGy twice 3 h apart, and PTH (1–34) (50 μg/kg) or vehicle control was administered 24 h later and daily for 3 wk. Mice were killed on d 31. A, Body weight, n = 6–8/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. respective NON IRR treatment. B, Spleen weight (as a percent of total body weight); n = 6–8/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. respective NON IRR treatment. C, Vertebral bone area/tissue area (BA/TA), n = 9–12/group; *, P < 0.005 vs. NON IRR vehicle; **, P < 0.001 vs. IRR vehicle; ***, P < 0.05 vs. NON IRR PTH. D, Representative images of vertebrae. E, Osteoclast numbers per linear bone perimeter, n = 4–9/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. respective vehicle control. F, Serum levels of OCN, n = 7–13/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. IRR vehicle. G, Serum levels of P1NP, n = 14–20/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. respective NON IRR vehicle or PTH; **, P < 0.05 vs. IRR vehicle. And H, Serum levels of TRAP5b, n = 11–17/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. NON IRR vehicle. All numerical data are means ± sem.

Effects of irradiation and PTH on bone

PTH in d 31 mice significantly increased the vertebral bone area in both nonirradiated and irradiated mice with a more significant 30% increase in bone area of irradiated mice (Fig. 2, C and D). Irradiation did not alter osteoclast numbers, which were elevated in PTH groups regardless of irradiation status (Fig. 2E). The bone turnover marker, OCN, was elevated in the serum with PTH; although this only reached statistical significance in the irradiated mice (Fig. 2F). The bone formation marker P1NP was lower in the serum of irradiated mice with significantly higher P1NP in the PTH-treated irradiated vs. vehicle-treated irradiated mice (Fig. 2G). The serum TRAP5b levels were reduced in irradiated mice with a small trend toward an increase with PTH in both groups (Fig. 2H).

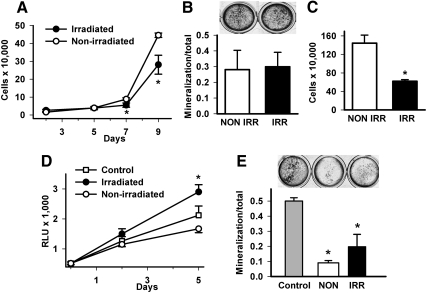

Effects of irradiation on osteoblastic cells: In vitro studies

Cell autonomous effects of irradiation on osteoblastic cells were analyzed to characterize the favored response of the irradiated mice to PTH anabolic actions. Calvarial osteoblasts were isolated from mice that had been irradiated (325 cGy, two fractions, 3 h apart) and then killed 3 d later and evaluated for proliferation and differentiation over time in vitro. The cell cultures from the irradiated mice had significantly lower cell numbers at d 7 and 9 vs. nonirradiated mice (Fig. 3A). There was no significant difference in the ability of cells from mice that were irradiated vs. nonirradiated to mineralize (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that irradiation did not confer a proliferative nor a differentiating advantage for osteoblastic cells and suggest that the actions of PTH to promote a more robust anabolic effect in the irradiated mice was conferred via another cell type.

Fig. 3.

Ex vivo effects of irradiation on osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. For primary effects of irradiation on osteoblastic/stromal cells, mice were irradiated (IRR) or not (NON IRR) with 325 cGy twice 3 h apart and primary calvarial cells collected 3 d later. A, Cells were plated to measure cell numbers over time via trypan blue cell enumeration (d 2–9), n = 4/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. same day NON IRR control. B, Cells were induced to mineralize over 21 d and stained via von Kossa method with mineralization area determination, n = 4–5/group. C, For effects of irradiation on bone marrow stromal cells, bone marrow was flushed from long bones of either irradiated mice or age-matched NON IRR mice 3 d after irradiation, plated at 1.3 million/well with fresh media changes every 2–3 d. Adherent cells were counted with trypan blue dye exclusion after 14 d, n = 4/group; *, P < 0.01 vs. NON IRR control. D, For effects of irradiated bone marrow on osteoblastic/stromal cells, primary bone marrow stromal cells were isolated from mice constitutively expressing luciferase and cultured to a monolayer. Bone marrow was then isolated from irradiated (325 cGy, two fractions 3 h apart) or NON IRR mice 3 d after irradiation and 1 × 106 marrow cells/group added to monolayer stromal cultures, where controls were stromal cells with no added bone marrow. Luciferase activity was determined at baseline, 2 and 5 d as a reflection of proliferative potential of the stromal cell population; *, P < 0.01 vs. NON IRR marrow. E, Calvarial osteoblasts from NON IRR mice were cultured to confluence and bone marrow from IRR or NON IRR mice was added, or control cultures without added bone marrow were induced to differentiate with ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate containing media. von Kossa staining was performed after 21 d to detect area of mineralization/total area, n = 5–6/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. control and NON IRR vs. IRR. All numerical data are means ± sem. RLU, Relative light unit.

Effects of irradiation on bone marrow cells: In vitro studies

To determine whether accessory cells in the bone marrow contributed to the preferred anabolic action of PTH in irradiated mice, bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were counted after ex vivo culture from irradiated and nonirradiated mice. There were significantly fewer BMSCs from irradiated mice (Fig. 3C). Effects of bone marrow from irradiated and nonirradiated mice on osteoblastic cell proliferation and differentiation were performed via coculture experiments. Bone marrow was harvested from mice 3 d after irradiation (325 cGy, two fractions, 3 h apart), and equal numbers of cells (1.0 × 106) were plated onto bone marrow stromal cells that had been previously isolated from mice constitutively expressing luciferase (13). Luciferase activity was determined at baseline, 2 and 5 d as a reflection of proliferative potential of the stromal cell population. Relative to control (luciferase BMSC only), bone marrow from nonirradiated mice resulted in lower luciferase activity, whereas bone marrow from irradiated mice resulted in significantly greater luciferase activity (Fig. 3D). The impact of irradiated bone marrow on osteoblastic differentiation was performed using calvarial osteoblasts from nonirradiated mice and adding bone marrow from irradiated or nonirradiated mice while inducing to differentiate (Fig. 3E). Control cultures (calvarial cells only) had the greatest amount of mineralized area. Both irradiated and nonirradiated bone marrow reduced mineralization of osteoblastic cultures, but irradiated bone marrow had significantly less reduction of mineralization vs. nonirradiated bone marrow. These data suggest that differences in the nonosteoblastic cells in the bone marrow were responsible for the augmented PTH response in irradiated mice.

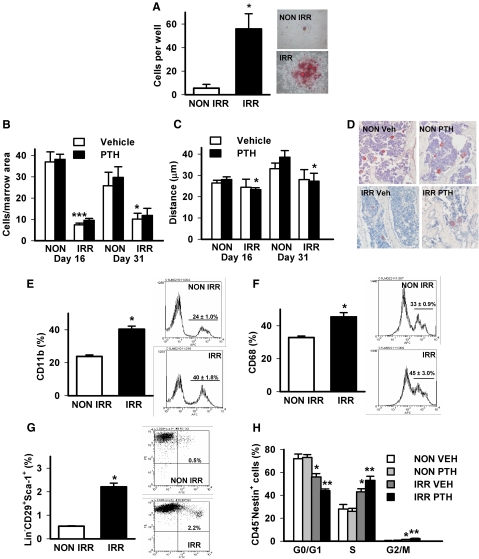

Effects of irradiation on other cells in the bone microenvironment

Because irradiation has been associated with increased bone marrow fat (20, 21), adipogenesis was assessed in bone marrow stromal cell cultures derived from irradiated mice. Oil Red O staining revealed increased adipocytes in the marrow 3 d after irradiation (Fig. 4A). Irradiation has also been associated with alterations in numbers and location of megakaryocytes relative to trabecular surfaces (22). The numbers and location of nonendothelial vWF positive cells in the bone marrow were evaluated 6 d (d 16) or 21 d (d 31) after irradiation of 10-d-old mice with PTH treatment initiated 24 h after irradiation (Fig. 4, B and C). Irradiation significantly reduced numbers of megakaryocytes in vertebral bone marrow with no impact of PTH. Irradiation led to a trend of decreased distance of megakaryocytes to bone (i.e. closer location), whereas PTH treatment resulted in a significantly shorter distance between megakaryocytes to bone at d 16 and 31 (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 4.

Effects of irradiation and PTH on cells in the bone marrow. Mice (d 10) were irradiated (IRR) or not (NON IRR) with 325 cGy twice 3 h apart. A, Bone marrow was isolated 3 d later, plated, and stained with Oil Red O to detect adipocytes, n = 4/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. NON IRR, representative image on right. B–D, Vertebral sections from mice irradiated with 325 cGy twice 3 h apart and administered PTH (1–34) (50 μg/kg) or vehicle control (VEH) for 5 d (d 16) or 21 d (d 31) were stained for vWF to detect (B) numbers of megakaryocytes/vertebral section, n = 4–9/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. d 31 NON IRR vehicle; ***, P < 0.001 vs. d 16 NON IRR vehicle; and (C) location of megakaryocytes relative to trabecular surfaces (distance), n = 4–9/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. same day NON IRR PTH. D, Representative images of vWF staining. E–H, Mice (d 10) were irradiated with 325 Cy/G twice 3 h apart at d 10, then treated with PTH (1–34) (50 μg/kg) or vehicle for 5 d; whole bone marrow was analyzed by flow cytometry to detect (E) CD11b+ cells, n = 9/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. NON IRR vehicle; (F) CD68+ cells, n = 5/group; *, P < 0.01 vs. NON IRR vehicle; (G) Lin−CD29+Sca-1+ cells, n = 9/group; *, P < 0.001 vs. NON IRR vehicle; (H) cell cycle phase of CD45−Nestin+ cells, n = 4–5/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. NON IRR vehicle; **, P < 0.05 vs. IRR vehicle. All numerical data are means ± sem.

Cells termed “osteomacs,” which are macrophage lineage cells lining the trabecular surfaces, have been found to support bone formation (23) and hence could be candidates for the enriched bone-forming environment created by irradiation. Two different macrophage markers were used to analyze cell populations 6 d after irradiation. Cells positive for CD11b were significantly increased in the marrow after irradiation (Fig. 4E). Cells positive for CD68 were also significantly increased in the marrow after irradiation (Fig. 4F).

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSC) have been proposed to be the target of PTH actions in the bone marrow (24), and hence the potential for irradiation providing a permissive environment for recruiting MSC was investigated. Because definitive markers for MSC have yet to be agreed upon, the current study used two different cell marker combinations to elucidate the impact 6 d after irradiation on MSC in the bone marrow. The percentage of Lin−CD29+Sca-1+ cells was significantly increased in the marrow of irradiated mice (Fig. 4G). A cell cycle analysis was performed in the population of CD45−Nestin+ cells in the bone marrow as described (24). Irradiation increased the CD45−Nestin+ cells in S and G2/M phase compared with nonirradiated mice (Fig. 4H). PTH increased the CD45−Nestin+ cells in S and G2/M phase in irradiated mice only.

Effects of irradiation and PTH on gene expression in the bone marrow microenvironment

Studies of gene expression were performed to characterize molecular events contributing to cellular and organ level changes with irradiation and PTH administration. Mice were irradiated at d 10, PTH treatment initiated, and mice killed after 5 d. In a submitted microarray dataset (GSE28819) (Gene Expression Omnibus; National Institutes of Health; National Center for Biotechnology Information), numerous genes were revealed that were regulated by irradiation and by PTH. Focus from the microarray data was given to three genes of interest, dentin matrix protein (DMP)1, periostin (POSTN), and IL-6.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to validate selected genes identified in the microarray analysis in addition to other candidate genes in the bone marrow of mice in the 5-d treatment study (Table 2). BMP2 and BMP6 were evaluated as genes associated with bone formation. There was no alteration in their expression with PTH treatment; however, irradiation significantly reduced their expression. FGF2 was evaluated as a growth factor previously associated with actions of PTH in bone (25). FGF2 expression was increased in nonirradiated mice treated with PTH and was even more significantly up-regulated in the irradiated vehicle-treated mice, suggesting that irradiation facilitated FGF2 production. In contrast to PTH treatment in nonirradiated mice, PTH did not induce an FGF2 increase in irradiated mice. PDGFB and IGF-I were evaluated as genes associated with proliferation. There were no significant changes in PDGFB with irradiation or PTH treatment. IGF-I levels were significantly increased with irradiation with no specific impact of PTH. SDF-1 was evaluated as a gene responsive to PTH and impacting hematopoietic cell homing (13, 26). PTH treatment of irradiated mice resulted in reduced SDF-1 mRNA in the marrow; otherwise, there were no significant changes.

Table 2.

Day 16 gene expression (6 d after irradiation)

| NON IRR VEH | NON IRR PTH | IRR VEH | IRR PTH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP2 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.01b | 0.07 ± 0.01b |

| BMP6 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.02b | 0.07 ± 0.01b |

| DMP1 | 1.62 ± 0.21 | 2.48 ± 0.38a | 1.80 ± 0.28 | 2.60 ± 0.50 |

| FGF2 | 1.23 ± 0.13 | 1.84 ± 0.22c | 3.19 ± 0.45d | 2.35 ± 0.31 |

| IGF1 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.05d | 0.22 ± 0.05 |

| IL-6 | 1.24 ± 0.26 | 1.41 ± 0.22 | 4.04 ± 1.13b | 3.44 ± 0.72b |

| PDGF | 41.7 ± 7.87 | 42.2 ± 7.99 | 27.4 ± 7.56 | 35.8 ± 8.12 |

| POSTN | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.01b | 0.12 ± 0.02b,e |

| SDF-1 | 1.16 ± 0.09 | 1.25 ± 0.13 | 1.30 ± 0.16 | 0.70 ± 0.01f |

| TGFβ | 0.55 ± 0.17 | 2.41 ± 0.54d | 1.23 ± 0.25a | 1.68 ± 0.56 |

n = 6–15/group. IRR, Irradiated; NON IRR, nonirradiated; VEH, vehicle control.

P = 0.05 vs. NON IRR VEH.

P < 0.05 vs. respective NON IRR VEH or PTH.

P < 0.05 vs. NON IRR VEH.

P < 0.01 vs. NON IRR VEH.

P < 0.05 vs. IRR VEH.

P < 0.01 vs. IRR VEH.

IL-6 gene expression was elevated in the bone marrow with irradiation in agreement with it providing a permissive state for PTH actions in bone marrow (11). There was a nonsignificant trend toward an increase in IL-6 with PTH treatment in nonirradiated mice (Table 2). DMP1 was identified in the microarray analysis as a gene up-regulated in response to PTH. Quantitative real-time PCR revealed a nonsignificant trend of increased DMP1 expression in bone marrow from nonirradiated and irradiated mice. POSTN levels were reduced in irradiated mice, and PTH treatment of irradiated mice significantly elevated POSTN.

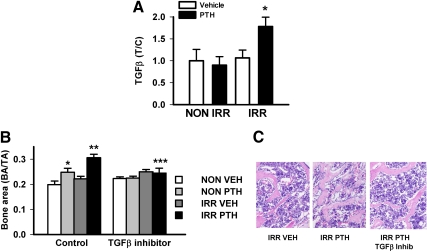

TGFβ gene expression was evaluated as a potential mediator of PTH anabolic actions in bone (7). PTH significantly increased TGFβ mRNA in nonirradiated bone marrow (Table 2). Irradiation significantly increased TGFβ mRNA with no further PTH effect. Because TGFβ is released in an inactive form, an ELISA was performed to detect active TGFβ protein (Fig. 5A). Mice that were irradiated and then treated with PTH had significantly elevated active marrow TGFβ protein. The impact of TGFβ on PTH actions in bone was evaluated by administering a TGFβ inhibitor (SB20512) concurrently with PTH. PTH increased vertebral bone area in nonirradiated and more significantly in irradiated mice (Fig. 5, B and C). Inhibition of TGFβ reduced the increase in bone area in the irradiated PTH-treated mice. There was a nonsignificant trend (P = 0.18) of the inhibitor blocking the PTH increase in bone area in nonirradiated mice.

Fig. 5.

Effects of irradiation and PTH on cells in the bone marrow. Mice (d 10) were irradiated (IRR) or not (NON IRR) with 325 cGy twice 3 h apart, 1 d later PTH (1–34) (50 μg/kg) or vehicle control was administered for 5 d, followed by killing, extraction of bone marrow, and ELISA detection for active TGFβ. A, Bone marrow levels of active TGFβ expressed as treatment/control where NON IRR vehicle is control, n = 14–16/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. all other groups. B, Mice (10 d) were irradiated (IRR) or not (NON-IRR), then 1 d later administered PTH or vehicle (VEH) with or without a TGFβ inhibitor for 20 d. Mice were killed, vertebrae harvested, and processed for bone histomorphometry, n = 4–9/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. NON IRR control vehicle; **, P < 0.01 vs. IRR control vehicle; ***, P < 0.05 vs. IRR control PTH. All numerical data are means ± sem. C, Representative images of vertebrae from IRR vehicle, IRR PTH, and IRR PTH treated with TGFβ inhibitor.

Discussion

Anabolic actions of PTH occur in association with an increase in hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow (10). How these two actions of PTH are linked has not been determined. This study identified several potential cellular mediators and local factors operative in the anabolic actions of PTH as well as demonstrating that altering the hematopoietic compartment in the marrow also impacts the action of PTH on bone formation. The model system used for this study, that of irradiation, has been used extensively to study alterations in the bone marrow cell population and dynamics of HSC renewal (27) with relatively few studies performed regarding the impact of irradiation on bone and/or on hormonal actions in bone. Interestingly, despite the dramatic depletion of cells in the bone marrow, irradiated mice had a preserved and even augmented anabolic response to PTH.

It has been proposed that irradiation creates an environment where despite widespread cell death, one or more cell types persist and provide support of osteoblast proliferation (22). HSCs are induced to enter the cell cycle with irradiation (28) and may account for the relatively increased hematopoietic progenitor cells (LSK) found in the present study. The cell surface marker CD41 is a marker of hematopoietic progenitors and cells of the megakaryocyte lineage. Megakaryocytes have been implicated as supportive cells due to their retention in the bone marrow after irradiation (29). Total body irradiation was previously reported to alter location but not numbers of megakaryocytes in the bone marrow with their location closer to the bone vs. the sinusoidal structures (22). This altered location was found to provide for megakaryocyte production of growth factors that stimulate osteoblast proliferation. In the present study, a reduction in megakaryocytic cells (identified as vWF positive cells) was found in the bone marrow with irradiation, which contrasts to the previous study result of equal numbers. Differences may be attributed to the different time frame where our study evaluated histological sections 5 d after irradiation and the previous study evaluated after 48 h, as well as the amount of radiation, which was sublethal in the present study. In addition, different markers were used for the identification of megakaryocytes in the two studies. Importantly, and similar to the previous study, we found that megakaryocytes were located closely to trabecular surfaces after irradiation. Megakaryocytes produce several growth factors, including TGFβ, PDGF, and FGF2, that are known to favor osteoblast proliferation (30, 31). Kacena et al. (32) reported that megakaryocytes stimulate osteoblast cell proliferation through a juxtacrine interaction. It is possible that the combined effect of megakaryocyte-derived growth factors in close proximity to bone and acting in conjunction with PTH on proliferating populations of mesenchymal stromal cells was effective in augmenting the PTH anabolic response.

Bone marrow ablation promotes new bone formation, suggesting that cells in the bone marrow play an inhibitory role toward osteoblasts (33), yet others report a growth promoting effect of bone marrow (34). In the present study, bone marrow was found to be inhibitory when cocultured with osteoblastic cells. A candidate cell type for the inhibition are adipocytes, because they negatively influence bone mass and osteoblastic activity (35). However, bone marrow from irradiated mice had higher numbers of adipocytes yet was less restrictive than bone marrow from control nonirradiated mice, suggesting that different cell types are likely important for this effect. The increase in adipocytes with irradiation may serve as a reservoir for HSC (36) and hence account for the relative protection found with hematopoietic progenitor cells during the stress associated with irradiation.

Our previous studies identified increased BrdU positivity in the bone marrow in histological sections from mice treated with PTH for 3 wk (13). In the present study, irradiation reduced overall BrdU positive cell numbers in hindlimbs at 6 d, and PTH treatment significantly elevated these numbers. Dual CD41 and BrdU labeling failed to show a PTH advantage, suggesting that hematopoietic cells were not responsible for the increase in proliferative potential, but instead, cell cycle analyses of MSC using the CD45−Nestin+ marker point to PTH elevating the MSC proliferative potential that occurred prominently in the bone marrow of irradiated mice.

Two BMPs were evaluated as genes associated with bone formation and also because they are produced by HSC in support of mesenchymal cell differentiation toward the osteoblast lineage (37). However, both were found to be reduced in the marrow after irradiation with no specific PTH effect. PDGF and FGF2 were evaluated because they are increased in the bone marrow after irradiation (22). FGF2 gene expression was increased in the marrow of nonirradiated mice with PTH treatment. This is consistent with reports that anabolic actions of PTH depend on FGF2 (25, 38). Interestingly, irradiation resulted in a greater increase in FGF2 in the marrow. PTH treatment in irradiated mice did not further alter FGF2; yet levels remained high, suggesting that irradiation may provide a permissive FGF2-supportive anabolic environment. FGF2 is also associated with the switch from adipogenesis to osteogenesis (39) and could represent a feedback control mechanism.

Three genes that arose of interest in the microarray analysis were DMP1, IL-6, and POSTN. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis demonstrated an increase in DMP1 with PTH administration, which reached statistical significance in the nonirradiated mouse bone marrow. This result was somewhat surprising, because DMP1 expression has been attributed to osteocytes and the harvest technique used in this study isolated bone marrow. However, marrow-derived stromal cells have been found to produce DMP1 upon osteogenic stimuli, and the increase in DMP1 is suggestive of the ability of PTH to increase cells in the marrow that are associated with a mineralization phenotype (40). IL-6 gene expression was increased in bone marrow of mice exposed to irradiation. Data from our laboratory have found IL-6 to be a critical mediator of the ability of PTH to inhibit apoptosis in hematopoietic cell populations in the bone marrow (11). Its role in the anabolic actions of PTH is unknown. POSTN is a matricellular protein localized to periosteal fibroblasts and periodontal ligament cells (41). Much of the work regarding POSTN has focused on its mechanical function (42); yet reduced trabecular bone was evidenced in the POSTN null mice substantiating a role in bone formation (43). POSTN was identified during fracture healing in undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and immature preosteoblastic cells (44), and POSTN-like factor was suggested to induce bone formation in the fracture healing callus (45). Interestingly, POSTN is produced in response to megakaryocyte-derived TGFβ (46). These data are suggestive of PTH under conditions of irradiation to provide signals to either stimulate the progression of mesenchymal stem cells in the marrow to differentiate to preosteoblastic cells or induce recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to trabecular surfaces to provide the anabolic actions of PTH.

Likely, the most important findings of this study center on TGFβ, which has been implicated as a key factor in PTH anabolic actions in bone via its release from active sites of bone resorption (7). The present study found that TGFβ mRNA was elevated with PTH treatment and levels of active TGFβ protein were elevated in the PTH-treated irradiated bone microenvironment. Blocking TGFβ with a specific inhibitor effectively reduced the PTH increase in bone area in irradiated mice. Because mice that had been irradiated did not have increased evidence of bone resorption and that this model is one of bone modeling vs. remodeling, this suggests an alternative source of TGFβ, one example of which could be megakaryocytes, is promoting mesenchymal stem cell recruitment to complement PTH actions on the skeleton.

In summary, irradiation in growing mice resulted in significant changes in the bone marrow and an augmentation of the anabolic actions of PTH on trabecular bone. These changes could not be attributed to cell autonomous effects on osteoblastic cells but were associated with increased numbers of CD11b, CD68 myeloid lineage cells, increased Lin−CD29+Sca-1+, and increased cycling CD45−Nestin+ mesenchymal stem like cells. Increased gene expression of IGF-I, FGF2, IL-6, and POSTN in response to irradiation in the bone marrow microenvironment likely supports PTH actions. Greater levels of active TGFβ from nonmatrix-derived sources in response to PTH appear responsible for mesenchymal stem cell recruitment in the skeletal environment of irradiation and augmented anabolic responses in the bone. These data substantiate that multiple factors, including the complement of hematopoietic cells, come into play when considering the anabolic mechanisms of PTH in bone.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Strayhorn for histologic assistance, Craig Johnson for statistical assistance with microarray analyses, and Jinhui Liao for immunohistochemical staining.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK53904.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- APC

- Allophycocyanin

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- BMSC

- bone marrow stromal cell

- BrdU

- bromodeoxyuridine

- cGy

- centigray

- DMP

- dentin matrix protein

- FGF-2

- fibroblast growth factor-2

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- LSK

- Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem/stromal cell

- OCN

- osteocalcin

- PDGF

- platelet-derived growth factor

- PE

- phycoerythrin

- P1NP

- procollagen type 1 amino-terminal peptide

- POSTN

- periostin

- SDF-1

- stromal-derived factor-1

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- vWF

- von Willebrand factor.

References

- 1. Aspenberg P, Genant HK, Johansson T, Nino AJ, See K, Krohn K, García-Hernández PA, Recknor CP, Einhorn TA, Dalsky GP, Mitlak BH, Fierlinger A, Lakshmanan MC. 2010. Teriparatide for acceleration of fracture repair in humans: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 102 postmenopausal women with distal radial fractures. J Bone Miner Res 25:404–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bashutski JD, Eber RM, Kinney JS, Benavides E, Maitra S, Braun TM, Giannobile WV, McCauley LK. 2010. Teriparatide and osseous regeneration in the oral cavity. New Engl J Med 363:2396–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wei G, Pettway GJ, McCauley LK, Ma PX. 2004. The release profiles and bioactivity of parathyroid hormone from poly(lactic co-glycoloic acid) microspheres. Biomaterials 25:345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adams GB, Martin RP, Alley IR, Chabner KT, Cohen KS, Calvi LM, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. 2007. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche. Nat Biotechnol 25:238–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poole KE, Reeve J. 2005. Parathyroid hormone- a bone anabolic and catabolic agent. Curr Opin Pharmacol 5:612–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nissenson RA, Jüppner H. 2008. Parathyroid hormone. In: Favus M. ed. Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. 7th ed Washington, DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 123–127 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu X, Pang L, Lei W, Lu W, Li J, Li Z, Frassica FJ, Chen X, Wan M, Cao X. 2010. Inhibition of Sca-1-positive skeletal stem cell recruitment by alendronate blunts the anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone on bone remodeling. Cell Stem Cell 7:571–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taichman RS. 2005. Blood and bone: two tissues whose fates are intertwined to create the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood 105:2631–2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Calvi LM, Sims NA, Hunzelman JL, Knight MC, Giovannetti A, Saxton JM, Kronenberg HM, Baron R, Schipani E. 2001. Activated parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor in osteoblastic cells differentially affects cortical and trabecular bone. J Clin Invest 107:277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. 2003. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 425:841–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pirih FQ, Michalski MN, Cho SW, Koh AJ, Berry JE, Ghaname E, Kamarajan P, Bonnelye E, Ross CW, Kapila YL, Jurdic P, McCauley LK. 2010. Parathyroid hormone mediates hematopoietic cell expansion through interleukin-6. PLoS One 5:e13657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Black DM, Greenspan SL, Ensrud KE, Palermo L, McGowan JA, Lang TF, Garnero P, Bouxsein ML, Bilezikian JP, Rosen CJ. 2003. The effects of parathyroid hormone and alendronate alone or in combination in postmenopausal osteoporosis. New Engl J Med 25:1207–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koh AJ, Demiralp B, Neiva KG, Hooten J, Nohutcu RM, Shim H, Datta NS, Taichman RS, McCauley LK. 2005. Cells of the osteoclast lineage as mediators of the anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone in bone. Endocrinology 146:4584–4596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Samadfam R, Xia Q, Goltzman D. 2007. Co-treatment of PTH with osteoprotegerin or alendronate increases its anabolic effect on the skeleton of oophorectomized Mice. J Bone Miner Res 22:53–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karsdal MA, Martin TJ, Bollerslev J, Christiansen C, Henriksen K. 2007. Are non-resorbing osteoclasts sources of bone anabolic activity? J Bone Miner Res 22:484–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamashita J, Datta NS, Chun YH, Yang DY, Carey AA, Kreider JM, Goldstein SA, McCauley LK. 2008. Role of Bcl-2 in osteoclastogenesis, cell survival, and PTH anabolic actions in bone. J Bone Miner Res 23:621–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Demiralp B, Chen HL, Koh AJ, Keller ET, McCauley LK. 2002. Anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone during endochondral bone growth are dependent on c-fos. Endocrinology 143:4038–4047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 2010. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B 57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosen CJ, Ackert-Bicknell C, Rodriguez JP, Pino AM. 2009. Marrow fat and the bone microenvironment: developmental, functional, and pathological implications. Crit Rev Eukar Gene 19:109–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naveiras O, Nardi V, Wenzel PL, Hauschka PV, Fahey F, Daley GQ. 2009. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature 460:259–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dominici M, Rasini V, Bussolari R, Chen X, Hofmann TJ, Spano C, Bernabei D, Veronesi E, Bertoni F, Paolucci P, Conte P, Horwitz EM. 2009. Restoration and reversible expansion of the osteoblastic hematopoietic stem cell niche after marrow radioablation. Blood 114:2333–2343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chang MK, Raggatt LJ, Alexander KA, Kuliwaba JS, Fazzalari NL, Schroder K, Maylin ER, Ripoll VM, Hume DA, Pettit AR. 2008. Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol 181:1232–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, Macarthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma'ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. 2010. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 466:829–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hurley MM, Yao M, Lane NE. 2005. Changes in serum fibroblast growth factor 2 in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis treated with human parathyroid hormone (1–34). Osteoporosis Int 16:2080–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jung Y, Wang J, Schneider A, Sun YX, Koh-Paige AJ, Osman NI, McCauley LK, Taichman RS. 2006. Regulation of SDF-1 (CXCL12) production by osteoblasts in the hematopoietic microenvironment and a possible mechanisms for stem cell homing. Bone 38:497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fliedner TM, Graessle D, Paulsen C, Reimers K. 2002. Structure and function of bone marrow hemopoiesis: mechanisms of response to ionizing radiation exposure. Cancer Biother Radio 17:405–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhong JF, Zhan Y, Anderson WF, Zhao Y. 2002. Murine hematopoietic stem cell distribution and proliferation in ablated and nonablated bone marrow transplantation. Blood 100:3521–3526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tanum G. 1984. The megakaryocyte DNA content and platelet formation after the sublethal whole body irradiation of rats. Blood 63:917–920 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Witte DP, Stambrook PJ, Feliciano E, Jones CL, Lieberman MA. 1988. Growth factor production by a human megakaryocytic tumor cell line. J Cell Physiol 137:86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang JC, Chang TH, Goldberg A, Novetsky AD, Lichter S, Lipton J. 2006. Quantitative analysis of growth factor production in the mechanism of fibrosis in agnogenic myeloid metaplasia. Exp Hematol 34:1617–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kacena MA, Gundberg CM, Horowitz MC. 2006. A reciprocal regulatory interaction between megakaryocytes, bone cells, and hematopoietic stem cells. Bone 39:978–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang Q, Cuartas E, Mehta N, Gilligan J, Ke HZ, Saltzman WM, Kotas M, Ma M, Rajan S, Chalouni C, Carlson J, Vignery A. 2008. Replacement of bone marrow by bone in rat femurs: the bone bioreactor. Tissue Eng Part A 14:237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bab I, Gazit D, Muhlrad A, Shteyer A. 1988. Regenerating bone marrow produces a potent growth-promoting activity to osteogenic cells. Endocrinology 123:345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Devlin MJ, Cloutier AM, Thomas NA, Panus DA, Lotinun S, Pinz I, Baron R, Rosen CJ, Bouxsein ML. 2010. Caloric restriction leads to high marrow adiposity and low bone mass in growing mice. J Bone Miner Res 25:2078–2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Han J, Koh YJ, Moon HR, Ryoo HG, Cho CH, Kim I, Koh GY. 2010. Adipose tissue is an extramedullary reservoir for functional hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood 115:957–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jung Y, Song J, Shiozawa Y, Wang J, Wang Z, Williams B, Havens A, Schneider A, Ge C, Franceschi RT, McCauley LK, Krebsbach PH, Taichman RS. 2008. Hematopoietic stem cells regulate development of their niche. Stem Cells 26:2042–2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hurley MM, Okada Y, Xiao L, Tanaka Y, Ito M, Okimoto N, Nakamura T, Rosen CJ, Doetschman T, Coffin JD. 2006. Impaired bone anabolic response to parathyroid hormone in Fgf2−/− and Fgf2+/− mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 341:989–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xiao L, Sobue T, Esliger A, Kronenberg MS, Coffin JD, Doetschman T, Hurley MM. 2010. Disruption of the Fgf2 gene activates the adipogenic and suppresses the osteogenic program in mesenchymal marrow stromal stem cells. Bone 47:360–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kalajzic I, Braut A, Guo D, Jiang X, Kronenberg MS, Mina M, Harris MA, Harris SE, Rowe DW. 2004. Dentin matrix protein1 expression during osteoblast differentiation, generation of an osteocyte GFP-transgene. Bone 35:74–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Horiuchi K, Amizuka N, Takeshita S, Takamatsu H, Katsuura M, Ozawa H, Toyama Y, Bonewald LF, Kudo A. 1999. Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor β. J Bone Miner Res 14:1239–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bonnet N, Standley KN, Bianchi EN, Stadelmann V, Foti M, Conway SJ, Ferrari SL. 2009. The matricellular protein periostin is required for Sost inhibition and the anabolic response to mechanical loading and physical activity. J Biol Chem 284:35939–35950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rios H, Koushik SV, Wang H, Wang J, Zhou HM, Lindsley A, Rogers R, Chen Z, Maeda M, Kruzynska-Frejtag A, Feng JQ, Conway SJ. 2005. Periostin null mice exhibit dwarfism, incisor enamel defects, and an early-onset periodontal disease-like phenotype. Mol Cell Biol 25:11131–11144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nakazawa T, Nakajima A, Seki N, Okawa A, Kato M, Moriya H, Amizuka N, Einhorn TA, Yamazaki M. 2004. Gene expression of periostin in the early stage of fracture healing detected by cDNA microarray analysis. J Orthopaed Res 22:520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu S, Barbe MF, Liu C, Hadjiargyrou M, Popoff SN, Rani S, Safadi FF, Litvin J. 2009. Periostin-like-factor in osteogenesis. J Cell Physiol 218:584–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Oku E, Kanaji T, Takata Y, Oshima K, Seki R, Morishige S, Imamura R, Ohtsubo K, Hashiguchi M, Osaki K, Yakushiji K, Yoshimoto K, Ogata H, Hamada H, Izuhara K, Sata M, Okamura T. 2008. Periostin and bone marrow fibrosis. Int J Hematol 88:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.