Abstract

Background and Objectives

Cardiac caregivers may represent a novel low-cost strategy to improve patient adherence to medical follow-up and guidelines and, ultimately, patient outcomes. Prior work on caregiving has been conducted primarily in mental health and cancer research; few data have systematically evaluated caregivers of cardiac patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the patterns of caregiving and characteristics of caregivers among hospitalized patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) to assess disparities in caregiver burden and to determine the potential for caregivers to impact clinical outcomes.

Subjects and Methods

Consecutive patients admitted to the cardiovascular service line at a university medical center during an 11-month period were included in the Family Cardiac Caregiver Investigation To Evaluate Outcomes (FIT-O) study. Patients (n = 4500; 59% white, 62% male, 93% participation rate) completed a standardized interviewer-assisted questionnaire in English or Spanish regarding assistance with medical care, daily activities, and medications in the past year and plans for posthospitalization. In univariate and multiple variable analyses, caregivers were categorized as either paid/professional (eg, nurse/home aide) or nonpaid (eg, family member/friend).

Results and Conclusions

Among CVD patients, 13% planned to have a paid caregiver and 51% a nonpaid caregiver at discharge. Planned paid caregiving was more prevalent among racial/ethnic minority versus white patients (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.2–1.8); planned nonpaid caregiving prevalence did not differ by race/ethnicity. Most nonpaid caregivers were female (78%). Patients who had nonpaid caregivers in the year prior to hospitalization (28%) reported grocery shopping/meal preparation (32%), transport to/arranging doctor visits (30%), and medication adherence/medical needs (25%) as top tasks caregivers assisted with. Following hospitalization, a majority of patients expect nonpaid caregivers, primarily women, to assist with tasks that have the potential to improve CVD outcomes such as medical follow-up, medication adherence, and nutrition, suggesting that these are important targets for caregiver education.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, caregiving, education, prevention

Low-cost novel approaches to increase adherence to prevention guidelines and improve quality outcomes are needed to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the leading cause of death and health care expenditures in the United States.1 Informal caregivers may be a unique opportunity to disseminate preventive strategies and improve the clinical outcomes of CVD patients.2,3 The prevalence of informal caregiving for patients with a variety of illness is estimated to be approximately 53 million Americans, yet few data have specifically examined the prevalence of available caregivers in the acute, recovery, and chronic phases of CVD.4–6 Individuals with long-term complex health problems such as CVD may often be assisted at home by family members who serve as informal caregivers.7

Despite the large quantity of research on caregiving and older adults,8–11 limited information is available regarding the prevalence of informal family cardiac caregivers.12 There is also a paucity of data that have examined racial and ethnic differences in cardiac caregiving patterns. Data from the Family Intervention Trial for Heart Health showed that caregivers of patients recently hospitalized with CVD may also be at risk of CVD because of not only shared genetic and lifestyle factors but also the strain associated with caregiving.12 There is a gap in the cardiac literature regarding the prevalence and characteristics of cardiac caregivers that could be useful to design targeted educational interventions for cardiac caregivers aimed to improve health outcomes and reduce health care costs.

The purpose of this study was to systematically evaluate patterns of caregiving and characteristics of caregivers among consecutive patients hospitalized with CVD during an 11-month period in a high-volume university hospital that serves a diverse population. The specific aims were to determine the prevalence of caregiving and if it varied by sex, racial/ethnic group, and other demographic characteristics and to assess the extent and type of caregiving provided before and expected after hospitalization. These data will be used to help design a targeted educational intervention aimed to reduce disparities and improve CVD clinical outcomes.

Methods

Design and Participants

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Family Cardiac Caregiver Investigation To Evaluate Outcomes (FIT-O) study is a prospective cohort study designed to evaluate the relation between cardiac caregiving and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with CVD. This study is a cross-sectional analysis of FIT-O baseline data from consecutive patients admitted to the cardiovascular service line at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center during an 11-month period between November 2009 and September 2010.

Hospital admission logs were reviewed daily to identify patients admitted to the cardiovascular service line. Trained bilingual research staff systematically distributed surveys (available in English and Spanish) to potential participants to assess whether they had or planned to have a caregiver and, if applicable, the type and extent of caregiving. Patients were excluded from survey administration if they were unable to read or understand English or Spanish, mental status precluded participation, or they refused to complete the survey. Hospital logs were checked weekly to detect any uncollected surveys. If uncollected surveys were detected, research staff attempted to contact the patient prior to discharge, or in the event this was not feasible, the survey was mailed with a prestamped return envelope for the patient to complete and return. Greater than 93% of consecutively admitted eligible patients completed the survey. The final study sample consisted of 4500 adult patients with CVD (38% female, 59% white; mean age, 65 [SD, 14] years). Data on patient demographics were collected retrospectively by standardized electronic chart review. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Caregiver Assessment

A caregiver was defined as a paid or nonpaid person who assists the patient with medical and/or preventive care. Caregiving and/or assistance with medical care and daily activities were classified into the following categories: (1) an unpaid family member or friend who assists the patient in complying with medical and lifestyle therapies (nonpaid caregiver), (2) a paid professional caregiver (eg, nurse/home aide), (3) organizational services (eg, Meals on Wheels, rides, cleaning services), (4) residence in a full-time nursing facility, or (5) none of the above. The survey assessed demographic characteristics of the nonpaid caregiver (age, race/ethnicity), his/her relationship to the patient, and the extent to which the nonpaid caregiver was expected to be involved in the patient’s posthospitalization care.

Standardized data were also collected on the specific nature of the tasks a caregiver performed/would perform after discharge, based on basic activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, in addition to tasks commonly associated with post-discharge cardiac care. Tasks included grocery shopping or meal preparation, transportation to doctor visits, taking medications or changing bandages, and dressing or bathing.

Survey questions were extensively pilot tested prior to study initiation. Reliability was assessed by surveying a subsample of patients at 2 different time points to determine agreement between responses (κ = 0.53, suggesting good reliability).

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Surveys were created and processed using the intelligent character recognition software EzDataPro32 (version 8.0.7; Creative ICR, Inc, Beaverton, Oregon) and ImageFORMULA (version Dr-2580C; Canon USA, Inc, New York). The data were double checked for errors and stored in a Microsoft Access database.

Descriptive data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Caregiving was categorized as having paid, nonpaid, any (either paid or nonpaid) caregivers, having organized services, and/or living in full-time nursing facility. χ2 Tests were performed to determine the association between patient sex and/or race/ethnicity and caregiving. Race/ethnicity was dichotomized as racial/ethnic minority (black/Hispanic/other) versus white. Analyses were repeated for caregiving before and after hospitalization.

Logistic regression models were used to evaluate predictors of caregiving adjusted for patient age, marital status, and health insurance status and were constructed for caregiving before and after hospitalization. Analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1. Mean age was 65 (SD, 14) years. Similar to the hospital cardiovascular service line census, nearly two-thirds of participants were men, and slightly more than half were white. Approximately 16% of the survey completers (n = 715) underwent cardiac surgery during their hospitalization. The majority of patients surveyed had 1 or more types of health insurance. Racial/ethnic minority patients were more likely to have Medicaid compared with white patients (odds ratio [OR], 5.6, 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.6–6.7).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Hospitalized CVD Population (n = 4500)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age Age ≥65 y | 2433 (54) |

| Race/ethnic group | |

| White | 2655 (59) |

| Hispanic | 873 (20) |

| Black | 554 (12) |

| Other | 186 (4) |

| Unknown | 232 (5) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 2777 (62) |

| Female | 1723 (38) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/life partner | 2171 (48) |

| Single | 1259 (28) |

| Divorced | 154 (3) |

| Widow | 350 (8) |

| Unknown | 566 (13) |

| Health insurance | |

| Yes | 3857 (86) |

| No | 643 (14) |

| Health insurance typea | |

| Commercial | 2756 (61) |

| Medicare | 2166 (48) |

| Medicaid | 674 (15) |

| Unknown | 409 (9) |

Abbreviation: CVD, cardiovascular disease.

May have more than 1 plan type.

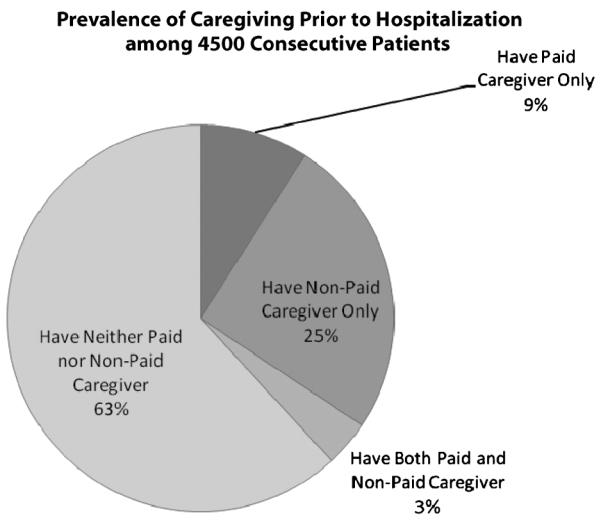

Prevalence of caregiving in the year prior to hospitalization among hospitalized CVD patients is presented in Figure 1, and results stratified by sex and race/ethnicity are shown in Table 2A. Overall, 37% of patients reported having a caregiver in the year prior to admission. Male patients were significantly less likely than female patients to have a paid caregiver but were more likely than female patients to have a nonpaid caregiver, such as a friend or a family member. Racial/ethnic minority participants were 1.3 times more likely than white participants to have a paid and/or nonpaid caregiver prior to hospitalization. When adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and health insurance status, the results were not materially different (men vs women with a paid caregiver: OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.6; men vs women with a nonpaid caregiver: OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.4; and racial/ethnic minorities vs whites with a paid and/or nonpaid caregiver: OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6).

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of caregiving prior to hospitalization for cardiovascular disease.

TABLE 2A.

Prevalence of Caregiving Prior to Hospitalization Among 4500 Cardiac Patients

| Patient Sex |

Patient Race/Ethnicitya |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Male | Female | OR Male vs Female |

Black/Hispanic/ Other |

White | OR Black/Hispanic/ Other vs White |

|

| n (%) | n (%)b | n (%)b | OR (95% CI) | n (%)b | n (%)b | OR (95% CI) | |

| Paid caregiverc | 546 (12) | 240 (9) | 306 (18) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 236 (15) | 258 (10) | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) |

| Nonpaid caregiverd | 1257 (28) | 818 (30) | 439 (26) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 453 (28) | 711 (27) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) |

| Any caregivere | 1656 (37) | 991 (36) | 665 (39) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 643 (40) | 893 (34) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) |

| Organized servicesf | 27 (1) | 13 (0.6) | 14 (1) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 10 (1) | 16 (1) | 1.0 (0.4–2.2) |

| Living in full-time nursing facilityg |

29 (1) | 11 (0.4) | 18 (1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 15 (1) | 13 (1) | 1.9 (0.9–3.9) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Values in bold are statistically significant P < .05.

Data of 232 participants were omitted because of unreported race/ethnic group.

% Is column percent.

Nurse, aide or home attendant.

Friend or family members.

Have either paid or nonpaid caregiver (nurse, aide, or home attendant, or friend or family member).

Meals on Wheels, rides, senior center, or cleaning services.

Live or have lived in a full-time nursing facility prior to hospitalization.

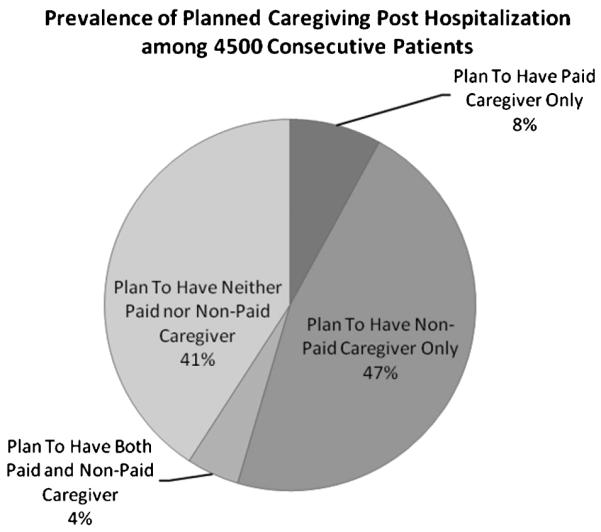

Prevalence of participants planning to have a cardiac caregiver after hospital discharge is presented in Figure 2, and results stratified by sex and race/ethnicity are shown in Table 2B. Overall, 59% of patients planned to have a cardiac caregiver after hospital discharge. Similar to caregiving patterns prior to hospitalization, male patients were significantly less likely than female patients to report plans to have a paid caregiver and were more likely than female patients to report plans to have a nonpaid caregiver. Racial/ethnic minority patients were significantly more likely than white patients to report plans to have a paid caregiver after discharge. However, there was no difference between racial/ethnic minority patients and white patients in the proportion planning to have a nonpaid caregiver after discharge. Results for patients reporting plans to have a paid caregiver remained significant in multivariable models adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and health insurance status (men vs women with plans to have a paid caregiver: OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7; racial/ethnic minorities vs whites with plans to have a paid caregiver: OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1–1.7).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of caregiving planned posthospitalization for cardiovascular disease.

TABLE 2B.

Prevalence of Planned Caregiving Posthospitalization Among 4500 Cardiac Patients

| Patient Sex |

Patient Race/Ethnicitya |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Male | Female | OR Male vs Female |

Black/Hispanic/ Other |

White | OR Black/Hispanic/ Other vs White |

|

| n (%) | n (%)b | n (%)b | OR (95% CI) | n (%)b | n (%)b | OR (95% CI) | |

| Paid caregiverc | 564 (13) | 246 (9) | 318 (18) | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 237 (15) | 280 (11) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) |

| Nonpaid caregiverd | 2303 (51) | 1482 (53) | 821 (48) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 781 (48) | 1393 (52) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| Any caregivere | 2661 (59) | 1630 (59) | 1031 (60) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 954 (59) | 1555 (59) | 1.0 (1.0–1.2) |

| Organized servicesf | 58 (2) | 31 (1) | 27 (2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 7 (1) | 40 (2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

| Living in full-time nursing facilityg |

47 (1) | 22 (1) | 25 (2) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 19 (1) | 25 (1) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Values in bold are statistically significant P < .05.

Data of 232 participants were omitted because of unreported race/ethnic group.

% Is column percent.

Nurse, aide or home attendant.

Friend or family members.

Have either paid or nonpaid caregiver (nurse, aide, or home attendant, or friend or family member).

Meals on Wheels, rides, senior center, or cleaning services.

Live or have lived in a full-time nursing facility prior to hospitalization.

Table 3 shows that most nonpaid caregivers were patient spouses/partners (57%), followed by sons/daughters (21%) and multiple family members/friends (10%). Nonpaid caregivers were more frequently female than male (78% vs 22%; Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of Nonpaid Caregivers

| Nonpaid Caregiver | Overall, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Spouse/partner | 1303 (57) |

| Son/daughter | 481 (21) |

| Multiple family members/friends | 226 (10) |

| Other family member | 134 (6) |

| Parent | 77 (3) |

| Friend | 50 (2) |

| Unknown | 32 (1) |

TABLE 4.

Burden of Nonpaid Caregiving by Nonpaid Caregiver Sex and Race After Hospitalization

| Nonpaid Caregiver Sexa |

Nonpaid Caregiver Race/Ethnicityb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Male | Female | Minority | White | |

| n (%) | n (%)c | n (%)c | n (%)c | n (%)c | |

| Nonpaid caregiverd | 2303 (51) | 495 (22) | 1742 (78) | 825 (39) | 1298 (61) |

Data of 66 nonpaid caregivers were omitted because of unreported sex.

Data of 180 nonpaid caregivers were omitted because of unreported race/ethnic group.

% Is row percent (proportion of nonpaid caregivers in each category).

Friend or family member.

Grocery shopping, or meal preparation, was the most common tasks CVD patients reported caregiver assistance with (Table 5). More than one-third of patients with a caregiver listed transportation to the doctor or arranging visits to the doctor, as a key task their caregiver assists them with as well. More than 1 in 4 patients with a nonpaid caregiver, and 32% of patients with any caregiver, reported caregiver assistance with medication compliance or medical needs such as taking blood pressure or changing bandages.

TABLE 5.

Frequency and Type of Assistance Provided by Cardiac Caregivers (N = 3069)

| Paid Caregiver |

Nonpaid Caregiver |

Paid or Nonpaid Caregiver |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Task | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Grocery shopping or meal preparation | 273 (9) | 991 (32) | 1224 (40) |

| Transportation to doctor visits or arranging visits to doctor | 271 (9) | 923 (30) | 1133 (37) |

| Taking medications or medical needs (blood pressure, bandages) | 285 (9) | 764 (25) | 983 (32) |

| ADLs: dressing, bathing, moving, walking, bathroom, eating, or feeding self | 255 (8) | 350 (11) | 535 (17) |

Abbreviation: ADLs, activities of daily living.

Discussion

This is one of the first systematic studies of patterns of cardiac caregivers in an acute setting; we documented that approximately half of patients planned to have nonpaid caregivers after hospitalization, suggesting that the opportunity for caregivers to impact outcomes is substantial. Three additional findings of this study are: (1) a disproportionate caregiving burden among women was identified regardless of the sex of the patient, (2) racial/ethnic minority groups were more likely than whites to report having a caregiver prior to hospitalization and plans to have one after discharge, and (3) common tasks nonpaid caregivers provided assistance to patients with were related to nutrition, medical follow-up, and medication adherence. These data suggest that targeted educational programs may be a unique and low-cost opportunity to extend preventive care in the outpatient setting and may have the potential to improve quality outcomes.

Similar to other studies examining caregiver prevalence among persons with chronic illnesses, our study documented that nonpaid caregiving was more frequently used by patients than paid caregiving services.13 A nationally representative random-digit-dial survey of caregiving in the United States conducted by AARP recently reported that more than 1 in 3 households have a nonpaid caregiver providing assistance to a patient and that heart disease, stroke, and diabetes are the top 3 health issues addressed by caregivers after old age, Alzheimer disease, cancer, and mental illness.14 In another study examining the prevalence of caregiving in a national sample, approximately 80% of respondents reported that a nonpaid caregiver would be available to them in case they needed one.15 Similar to our study, this study also linked patient female sex, white race/ethnicity, and unmarried status to lower odds of having a caregiver compared with patient male sex, racial/ethnic minority status, and those who are married.16

It is not surprising that most nonpaid caregivers identified in our study were female, primarily spouses and daughters. This is consistent with other studies that indicate that women, specifically spouses, are more often the caregivers of patients with chronic illnesses compared with men.14–17 Previous research has also shown that female caregivers experience higher levels of caregiver burden and depression and lower levels of physical health and well-being compared with male caregivers.17 However, adverse health outcomes are not limited to female caregivers. High caregiver strain has been linked to increased stroke risk among both male and female caregivers, with higher risk observed among men, particularly African American men.18

Several studies suggest that it is necessary to develop sex-specific interventions to reduce the caregiving burden and stressors associated with the caregiver role.17,19 Interventions designed to educate and support the specific needs of female and male cardiac caregivers have the potential to reduce adverse health conditions that may hamper the ability of the caregiver to assist the patient. Given that most nonpaid caregivers are spouses or blood relatives of the hospitalized CVD patient and may share genetic and/or lifestyle risk, it is possible that an educational intervention may have beneficial outcomes for both the patient and the caregiver.

In this study, racial/ethnic minority cardiac patients were more likely than whites to have or plan to have a caregiver. These findings are consistent with recently identified trends that show racial/ethnic minority patients use caregivers more frequently compared with whites.13,15 One possible explanation for this is that, in our study, racial/ethnic minority patients were more likely to have Medicaid compared with whites and therefore may be more likely to have the type of insurance that provides for these services. Racial/ethnic minorities also experience greater risk of CVD compared with whites in the United States.1 Increased utilization of caregiving among racial/ethnic minorities represents a potential low-cost opportunity to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in CVD through educating caregivers about evidence-based guidelines for prevention.

Consistent with our observations, services frequently provided by nonpaid caregivers to patients in chronic care settings include transportation (83%), grocery shopping (75%), and meal preparation (65%).14 Our study documented that assistance with medications was a common task nonpaid caregivers attended to, which is consistent with data showing that, nationally, 9 of 10 caregivers reported their care recipient requires prescription medications.14 Medication nonadherence has been shown to be a prevalent problem among CVD patients, and caregivers may be a unique opportunity to improve medication adherence and clinical outcomes.

Strengths of this study include systematic data collection in a high-cardiac-volume hospital with greater than 93% completion rate, suggesting minimal selection bias. Representation of racial and ethnic minorities was significant in this study, which was enhanced by bilingual research staff. This study also had limitations including broad categorization of caregiving (eg, paid, nonpaid, or none), which could be interpreted or defined differently by patients. However, systematic survey administration renders differential categorization of caregiving by age or race/ethnicity unlikely. Although this was one of the largest studies conducted on cardiac caregivers of hospitalized patients, the sample sizes within racial/ethnic strata limit the generalizability to specific populations.

In conclusion, caregiving is prevalent among hospitalized CVD patients, especially racial and ethnic minorities, and women were documented to carry a disproportionate burden of nonpaid caregiving compared with men. Assistance most commonly provided by cardiac caregivers was related to nutrition, medical follow-up, and medication adherence, suggesting that educational programs targeted to nonpaid caregivers may represent a novel low-cost opportunity to improve CVD outcomes.

What’s New and Important.

■ Nearly half of all hospitalized cardiac patients have or will have nonpaid cardiac caregivers.

■ Nonpaid caregivers are more frequently female than male, and racial/ethnic minority patients are more likely than white patients to have a caregiver prior to admission.

■ The most common tasks associated with nonpaid caregiving were related to nutrition, medical follow-up, and medication adherence.

■ These results indicate that nonpaid caregivers of cardiac patients may represent a low-cost opportunity to improve CVD outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2RO1 HL075101) (principal investigator, Dr Mosca). Dr Mochari-Greenberger was supported by an NIH T32 training grant (HL007343).

Contributor Information

Lori Mosca, Columbia University Medical Center, Director, Preventive Cardiology, New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York..

Heidi Mochari-Greenberger, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Brooke Aggarwal, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Ming Liao, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Niurka Suero-Tejeda, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Mariceli Comellas, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Lisa Rehm, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Tianna M. Umann, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

Roxana Mehran, Columbia University Medical Center, New York..

REFERENCES

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RD, Brown TM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2010: an update from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pyke SDM, Wood DA, Kinmonth AL, Thompson SG. Change in coronary risk and coronary risk factor levels in couples following lifestyle. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:354–360. doi: 10.1001/archfami.6.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, Bartolucci AA, Giger JN. Telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke. 2002;33:2060–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020711.38824.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKune S, Andresen EM, Zhang J, Neugard B. Caregiving: A National Profile and Assessment of Caregiver Services and Needs. Rosalyn Carter Institute for Caregiving; Americus, GA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Characteristics and health of caregivers and care recipients—North Carolina, 2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(21):529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal B, Mosca L. Heart disease risk for female cardiac caregivers. Female Patient. 2009;34:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):224–228. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059337. [published online ahead of print December 28, 2006] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire L, Bouldin EL, Andresen EM, Anderson LA. Examining modifiable health behaviors, body weight, and use of preventive health services among caregivers and non-caregivers aged 65 years and older in Hawaii, Kansas, and Washington using 2007 BRFSS. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(5):373–379. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitaliano PP, Katon W. Unützer J. Making the case for caregiver research in geriatric psychiatry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(10):834–843. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassie KM, Sanders S. Familial caregivers of older adults [review] J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;50(suppl 1):293–320. doi: 10.1080/01634370802137975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal B, Liao M, Christian A, Mosca L. Influence of caregiving on lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors among family members of patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):93–98. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: a 20 year review (1980-2000) Gerontologist. 2002;42:237–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP [Accessed May 29, 2010];Caregiving in the US. 2009 http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf.

- 15.Roth DL, Haley WE, Wadley CG, Clay OJ, Howard G. Race and gender differences in perceived community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47:721–729. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelt DC, Schulz R, Chelluri L, Pinsky MR. Patient-specific, time varying predictors of post-ICU informal caregiver burden: the caregiver outcomes after ICU discharge project. Chest. 2009;137:88–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources and health: an updated meta-analysis. Gerontology. 2006;1:33–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.p33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haley WE, Roth DL, Howard G, Stafford MM. Caregiving strain and estimated risk for stroke and coronary heart disease. Stroke. 2010;41:331–336. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang B, Luttick ML, Dracup KJ, Jaarsma T. Family caregiving for patients with heart failure: types of care provided and gender differences. J Card Fail. 2010;16:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]