Abstract

Objectives:

The recent years have seen a surge in the prevalence of both diabetes and hypertension. Significant demographic variations reported on the prevalence patterns of diabetes and hypertension in India establish a clear need for a nation-wide surveillance study. The Screening India's Twin Epidemic (SITE) study aimed at collecting information on the prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes and hypertension cases in outpatient settings in major Indian states to better understand disease management, as well as to estimate the extent of underlying risk factors.

Materials and Methods:

During 2009–2010, SITE was conducted in eight states, in waves – one state at a time. It was planned to recruit about 2000 patients from 100 centers per wave. Each center enrolled the first 10 eligible patients (≥18 years of age, not pregnant, signed data release consent form, and ready to undergo screening tests) per day on two consecutive days. Patient demographics, medical history, and laboratory investigation results were collected and statistically interpreted. The protocol defined diabetes and hypertension as per the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommendations, respectively.

Results:

After the first two pilot phases in Maharashtra and Delhi, the protocol was refined and the laboratory investigations were simplified to be further employed for all other states, namely, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat.

Conclusion:

SITE's nation-wide approach will provide a real-world perspective on diabetes and hypertension and its contributing risk factors. Results from the study will raise awareness on the need for early diagnosis and management of these diseases to reduce complications.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, India, management, prevalence, risk factors, screening protocol

INTRODUCTION

The global prevalence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension is rising at an alarming rate.[1] Situation in India is particularly serious. The Fourth Diabetes Atlas, published by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), revealed that there were an estimated 50.8 million cases of diabetes in India in 2010. This number is predicted to rise to almost 87 million people by 2030.[1]

Data on hypertension, available from several regional studies, indicate an increase of about 30 times among urban Indians and 10 times among rural Indians, within a span of three and six decades, respectively.[2] To date, no nation-wide epidemiological study aimed at determining the prevalence of hypertension has been reported.

Furthermore, diabetes and hypertension serve as potential risk factors for one another.[3] Hypertension is 1.5–2 times more prevalent in diabetic as in non-diabetic individuals and about 30–35% of hypertensives are detected to have diabetes.[4] The combination of diabetes and hypertension imparts an additive risk and accelerates progression of both microvascular[5] and macrovascular complications.[6] Hence, these two conditions contribute significantly to the growing load of cardiovascular diseases and lead to a high economic burden that accounts for 5–20% of the total Indian healthcare expenditure.[7]

This rapid increase in diabetes and hypertension in India is most likely to result in a twin epidemic. Epidemiological studies determining the extent of the disease prevalence are highly warranted. The Screening India's Twin Epidemic (SITE) study was aimed at determining the number of diagnosed and undiagnosed cases of diabetes and hypertension in India and reporting the measures employed to manage and control these diseases in an outpatient setting. The study was conducted in eight states – Maharashtra, Delhi, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat. Although SITE is not a population-based study, it is one of the largest studies of its kind. Also, in lieu of poor existing information, SITE serves as a good proxy for providing valuable insights on the national prevalence and management of both diabetes and hypertension. We present herewith the SITE study design, methodologies and highlight the amendments made as the study progressed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

SITE was a cross-sectional, national, multicentric, non-randomized, observational study. The primary objective of the study was to estimate the prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes and hypertension in outpatient settings in major Indian states. The secondary objectives included estimation of the prevalence of other cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia, obesity [body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), and waist-hip ratio (WHR)], metabolic syndrome, urine microalbuminuria, arrhythmia, diet, smoking and alcohol consumption; estimation of the prevalence of abdominal obesity in sub-groups of patients (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smokers and alcoholics ); and understanding the management and the level of control of hypertension and diabetes. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for Good Epidemiology Practices.[8] The protocol complied with recommendations of the 18th World Health Congress (Helsinki, 1964) and the local laws and regulations of India.

Sample size calculation

The sample size depended on the expected prevalence of diabetes/hypertension (whichever was lower). Based on the conservative expected prevalence of 15% for diabetes,[9,10] it was determined that a sample size of 1225 patients was required per state. Assuming a dropout rate of 39%, it was estimated that 2000 patients were required to ensure 95% confidence such that the prevalence of diabetes is between 13% and 17%, that is, 15% ± 2% in each state.

Sampling design

India is the seventh largest and the second most populous country of the world. It is divided into 28 states and 7 union territories. It was initially planned to conduct the study in 10 states across five zones, North, South, East, West and Central, in waves – one state at a time – and recruit 2000 patients from 100 centers per wave.

Physician selection: The study was conducted in outpatient settings and the data were collected from general practitioners rather than specialists. This was done to assess evidence – practice gaps at the primary care physicians’ level in India. Also, the source of any potential bias was much reduced, as the number of people presenting the disease would evidently be higher at a specialist clinic rather than a general practitioner's clinic.

Patient selection: Patients ≥18 years of age and those ready to sign the data release consent form along with an acceptance to take the screening tests were included in the study. Female patients with known pregnancy were excluded from the study. Pregnant women are predisposed to gestational diabetes and weight gain, and their exclusion decreased eventual confounding effects on the results.

The first 10 patients visiting the physicians’ clinic on two consecutive days, irrespective of the purpose of the visit, and satisfying the inclusion criteria, were selected for the study.

Study waves

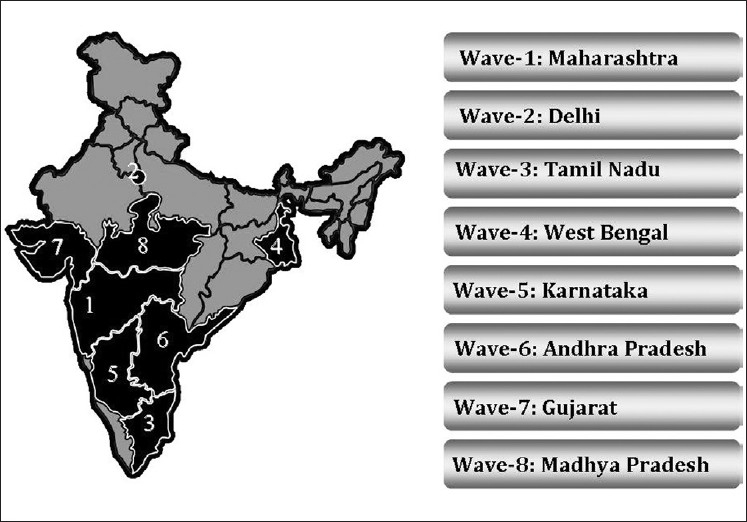

During 2009–2010, SITE was conducted in 8 states including 7 of the top 10 most populous Indian states and the National Capital Territory [Figure 1]. For the remaining two planned states, operational issues were to lead to an unanticipated delay in the study completion. On the basis of the fact that the sample size was calculated per state and that a low dropout rate was observed among the patients enrolled, the national coordinators deemed the data adequate to pan out substantial results. So, by the end of the 8th wave, the recruitment was declared completed. Because of a national multicentric approach of the study, the data obtained were representative of diverse demographic populations within India.

Figure 1.

The states in which the Screening India's Twin Epidemic study was conducted

Training

The study was sponsored by sanofi-aventis (India). Central laboratory services were provided by Metropolis Healthcare Ltd. Site management organization (SMO) and data management services were provided by Max Neeman Ltd. The sponsor ensured that the central laboratory, SMO, and data management personnel dedicated to study, as well as the participating physicians, received adequate training on various aspects of the study. Thus, the complete study team was well versed with the data collection form (DCF) and the study procedures were executed uniformly.

Methods

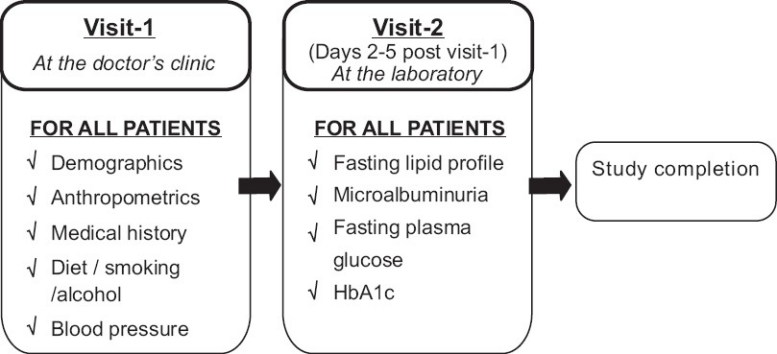

The data collection process was carried out in two steps [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Data collection process of the Screening India's Twin Epidemic study

At visit 1

The DCF used was designed in line with the study objectives. It captured details on the following aspects: demographics (age and gender), anthropometrics (height, weight, waist and hip circumference), behavioral (smoking and alcohol use), medical history (diabetes and its treatment, hypertension and its treatment, and cardiovascular diseases like ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction and stroke), type of diet (vegetarian/non-vegetarian), and family history of diabetes and hypertension. Details on the patient's socioeconomic, educational, psychosocial, and physical activity status were not collected.

Anthropometric measurements: Height was measured without shoes, in centimeters, using a standard stadiometer. Weight was measured with light clothes and without shoes, in kilograms, using a professional calibrated weighing scale, and rounded off to the nearest number. Since no standard weighing machine was employed, inter-instrument variations cannot be ruled out. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula: weight (kg)/height (m2).

The hip and waist measurements were taken using a standard non-stretchable anthropometric measure tape across all study sites. The hip circumference (HC) was measured over light clothing. The patient was made to stand erect with arms at the sides, feet placed together with weight equally distributed on each leg, and the gluteal muscles relaxed. The tape was placed horizontally around the point of the maximum posterior extension of the buttocks. The measurement was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. The patient's measured HC was calculated as the mean of the two observations or the mean of the two closest measurements. The WC was taken without clothing around the waist. The patient was made to stand erect with arms at the sides and feet placed about 25–30 cm apart with weight equally distributed on each leg. The WC was measured at the part of the trunk located midway between the lower costal margin and the iliac crest. The measurer stood beside the patient and made the tape fit snugly, without compressing any underlying soft tissues. The circumference was measured in centimeters to the nearest 0.5 cm at the end of a normal expiration. The method and angles of measurement were adequately detailed to ensure limited variance in the technique. WHR was calculated by dividing the WC (cm) by the HC (cm).

Blood pressure (BP) measurement: A mercury sphygmomanometer was used to measure the BP, preferably from the right arm of the patient. The BP was measured after the patient sat comfortably for 5 minutes. An average of two readings, recorded at 5-minutes interval, was taken to ensure accuracy.

At the end of visit 1, patients received a coupon of identification and were required to visit any of the nearest metropolis clinical diagnostic centers, within 2-5 days.

At visit 2

Fasting lipid profile, microalbuminuria, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and HbA1c were determined for each patient presenting a valid coupon.

HbA1c was measured by the Bio-Rad D10 high-pressure liquid chromatography method. Urine microalbumin was measured by a turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay technique and enzymatic reactions were applied to quantify total cholesterol (cholesterol esterase), high-density lipoproteins (HDL; cholesterol oxidase, esterase, and peroxidase), and triglycerides (TG; lipoprotein lipase, glycerol kinase, glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase, and peroxidase). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) was also calculated by using Friedewald's equation for TG <300 mg/dl.

Definitions and diagnostic criteria

Study population identification complied with the general guidelines for detecting diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes was diagnosed according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines,[11] and hypertension was classified according to the recommendations of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7).[12] Metabolic syndrome was diagnosed on the basis of National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP).[13]

BMI was categorized into normal (<23 kg/m2), overweight (23–25 kg/m2) and obese (>25 kg/m2), according to the guidelines jointly suggested by the Indian Health Ministry, Diabetes Foundation of India, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Indian Council of Medical Research, and National Institute of Nutrition and 20 other institutions.[14] Normal and truncal obesity was categorized according to the WHR, as suggested by the NCEP.[13]

Fasting lipid profile revealed the total cholesterol, TG, HDL-cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol levels. Of these, elevated TG (≥150 mg/dl) and concomitant low HDL-cholesterol (<40 mg/dl) were used to identify dyslipidemia.[15] The criteria used are (1) primarily attributed to atherogenic dyslipidemia, (2) linked to insulin resistance, (3) measurable during the initial phase of development of metabolic syndrome, (4) individually extremely inheritable, (5) simple to measure, and (6) determinants of the atherogenic index of plasma (AIP), a key prognostic marker of cardiovascular disease, calculated as log (TG/HDL-C).[16,17]

Urine microalbumin was defined according to the albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) as normoalbuminuria (ACR < 30 μg/mg), microalbuminuria (30–300 μg/mg), and macroalbuminuria (>300 μg/mg).[18]

Quality control

Monitoring visits were randomly conducted for at least 20% of the active sites (enrolled at least one patient) and the reports documented.

Phlebotomy services, testing, processing, shipment of blood and urine samples, and preparation and distribution of reports were undertaken by the central laboratory (Metropolis Healthcare Ltd.).

Data were managed centrally by Max Neeman International Ltd. Data entry, verification, and validation were carried out using PheedIt® database system, version 3.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A double-entry method was used to ensure that the data (except comments) were transferred accurately from the DCFs to the database. Moreover, every modification in the database could be traced using an audit trail. A data checking plan was established to define all automatic validation checks, as well as the supplemental manual checks. All discrepancies were researched until resolved.

Additionally, a National Steering Committee comprising India's leading endocrinologists and cardiologists was established to provide scientific direction for the study.

Statistical considerations

The total sample number, mean, standard deviation, and range (minimum and maximum) were calculated for all continuous variables (age, height, WC, HC, and lipid values), and frequency and percentage were calculated for all categorical variables (gender, presence of hypertension and diabetes and their treatment, smoking status, and urine microalbuminuria). Student's t-test and chi-square test were used to make comparisons between groups, with P value <0.05 considered statistically significant. A multivariate analysis was performed to estimate the association of hypertension and diabetes with dyslipidemia, obesity, metabolic syndrome, microalbuminuria, arrhythmia, smoking, alcohol consumption, and diet. A simple linear regression analysis was performed to estimate the contribution of individual variables to systolic and diastolic BP. Relative risk for developing diabetes and hypertension was calculated by assessing the following variables: age, gender, BMI, WHR, family history of diabetes and hypertension, and smoking status.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Screening studies play a very important role in determining the trends of disease prevalence; such trends can provide valuable insight regarding necessary corrective measures that can be implemented in a given population. India has witnessed a constant increase in the prevalence of diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. However, most previous reports on the prevalence of both diabetes and hypertension are either regional or vary in methodologies and sampling frames.

SITE aims not only to indicate the most accurate prevalence data of diabetes and hypertension in an outpatient setting in India at the state, regional, and national levels, but also to raise awareness on the need for early diagnosis and on the management of these diseases to reduce complications.

The study was conducted in eight states across India. After wave-1 and wave-2, the protocol was refined and the laboratory investigations simplified and then employed for all other subsequent waves.

During the first wave conducted in Maharashtra, the investigations included: random blood sugar (RBS; in all patients), electrocardiogram (ECG; in patients ≥40 years of age), and HbA1c (in known cases of diabetes) at visit-1; and the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT; in patients with RBS ≥140 mg/dl) and microalbuminuria test (in patients with RBS ≥140 mg/dl and in patients with hypertension) at visit-2. The OGTT involved a lengthy procedure that was logistically difficult to perform in general clinics. Additionally, a high dropout rate was observed among patients scheduled for the OGTT. Going forward, this attrition could have potentially introduced a bias in the study results.

Thus, based on the experiences of the pilot study in Maharashtra, certain protocol improvements were suggested for the second wave conducted in the National Capital Territory, Delhi. The ADA recommends either OGTT or FPG and disease-related symptoms (polydipsia, polyuria, and unexplained weight loss) for the confirmation of diabetes.[19] During wave-2, the OGTT was not performed; FPG was measured for all unknown cases of diabetes, as opposed to RBS in the pilot study. Though signs and symptoms of diabetes were recorded in this amended protocol, they did not play a decisive role in diagnosing new cases of diabetes. The microalbuminuria test was conducted for all patients. Additionally, specifications with regard to alcohol consumption and diet of patients were included in the DCF. Alcohol consumption and diet are established high-risk factors leading to the development and progression of diabetes and hypertension. Since significant regional differences exist in the Indian diet, it would be interesting to assess if a correlation exists between the regional prevalence of these diseases and diet. To establish a connection between lifestyle factors (diet and alcohol consumption) and prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, it was essential to include these elements in the study. This inclusion also broadened the scope of secondary analyses to be performed with the results of this study.

During wave-2, difficulties in maintaining uniformity in the ECG recordings and in dealing with logistical hurdles of organizing the ECG test at the sites surfaced. The inability to standardize ECG testing in a study of this magnitude would lead to inaccurate data generation. Hence, ECG tests were discontinued from wave-3 onward. Additionally, as an effort to further simplify the protocol, the FPG and HbA1c testing was conducted in all patients from wave-3 onward. This increased the cost of conducting the study. However, by employing HbA1c as a screening tool as per the newly proposed guidelines released in July 2009,[20] our approach to diagnosing diabetes was further simplified. Additionally, the correlation between FPG and HbA1c for the diagnosis of diabetes could also be studied.

An important limitation of this study is the reliance on a single-day FPG and BP measurement to detect new cases of diabetes and hypertension, respectively. Also, owing to the cross-sectional nature of our study, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Nonetheless, SITE is one of the largest prevalence studies on diabetes and hypertension conducted in outpatient settings in India. Due to the national multicentric approach of the SITE study, the data obtained are representative of diverse demographic populations within India.

The amendments to the SITE protocol were efforts made to maintain consistency and accuracy of the data collected as the study progressed through each subsequent wave. The wave-3 protocol (conducted in Tamil Nadu) reflected the most adequate data collection process for this study and was employed for all other waves, permitting robust analyses.

In conclusion, SITE will provide a real-world national perspective on diabetes and hypertension and their contributing risk factors. It will identify practice variations across states and evaluate compliance to international guidelines for the management of diabetes and hypertension. The standardization of the data collection process and the data analyses will justify various comparisons. The study will raise awareness on the need for early diagnosis and management of disease to reduce complications. SITE data will be useful for national recommendations, policies and guidelines, and will also support future exploratory researches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We duly thank the state coordinators and all the participating physicians. We would also like to thank the following employees of sanofi-aventis (India): Dr. Deepa Chodankar and Ms. Sonali Suratkar for reviewing the statistical analyses; Ms. Anahita Gouri for drafting and editing this manuscript; and Dr. Bhaswati Mukherjee, Dr. Azeem Kathawala and Dr. Chirag Trivedi for their critical inputs and periodic reviews.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pradeepa R, Mohan V. Hypertension and pre-hypertension in developing countries. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128:688–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein M, Sowers JR. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;19:403–18. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.5.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahay API-ICP Guidelines on Diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parving HH, Andersen AR, Smidt UM, Oxenboll B, Edsberg B, Christiansen JS. Diabetic nephropathy and arterial hypertension. Diabetologia. 1983;24:10–2. doi: 10.1007/BF00275939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams G. Hypertension in diabetes. In: Pickup J WG, editor. Textbook of diabetes. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1991. pp. 719–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das S MR, Patnaik UK. Management of hypertension in diabetes mellitus. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2001;2:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Federation of the International Epidemiologist Association (IEA): Good epidemiological practice (GEP) proper conduct in epidemiologic research. Berne: European Federation of the International Epidemiologist Association. [Last updated on 2004 Jun]; Available from: http://www.dundee.ac.uk/iea/GoodPract.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohan V, Deepa M, Deepa R, Shanthirani CS, Farooq S, Ganesan A, et al. Secular trends in the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in urban South India--the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-17) Diabetologia. 2006;49:1175–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramachandran A, Mary S, Yamuna A, Murugesan N, Snehalatha C. High prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors associated with urbanization in India. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:893–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misra A, Chowbey P, Makkar BM, Vikram NK, Wasir JS, Chadha D, et al. Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyszynski DF, Waterworth DM, Barter PJ, Cohen J, Kesaniemi YA, Mahley RW, et al. Relation between atherogenic dyslipidemia and the Adult Treatment Program-III definition of metabolic syndrome (Genetic Epidemiology of Metabolic Syndrome Project) Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobiasova M. Atherogenic index of plasma [log(triglycerides/HDL-cholesterol)]: Theoretical and practical implications. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1113–5. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eknoyan G, Levin N. NKF-K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines: Update 2000.Foreword. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(1 Suppl 1):S5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S12–54. doi: 10.2337/dc08-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1327–34. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]