Abstract

Loss to follow-up is often hard to avoid in randomised trials. This article suggests a framework for intention to treat analysis that depends on making plausible assumptions about the missing data and including all participants in sensitivity analyses

The intention to treat principle requires all participants in a clinical trial to be included in the analysis in the groups to which they were randomised, regardless of any departures from randomised treatment.1 This principle is a key defence against bias, since participants who depart from randomised treatment are usually a non-random subset whose exclusion can lead to serious selection bias.2

However, it is unclear how to apply the intention to treat principle when investigators are unable to follow up all randomised participants. Filling in (imputing) the missing values is often seen as the only alternative to omitting participants from the analysis.3 In particular, imputing by “last observation carried forward” is widely used,4 but this approach has serious drawbacks.3 For example, last observation carried forward was applied in a recent trial of a novel drug treatment in Alzheimer’s disease.5 The analysis was criticised because it effectively assumed that loss to follow-up halts disease progression,6 but the authors argued that their analysis was in fact conservative.7 Increasingly, trialists are expected to justify their handling of missing data and not simply rely on techniques that have been used in other clinical contexts.8

To guide investigators dealing with these tricky issues, we propose a four point framework for dealing with incomplete observations (box). Our aim is not to describe specific methods for analysing missing data, since these are described elsewhere,9 10 but to provide the framework within which methods can be chosen and implemented. We argue that all observed data should be included in the analysis, but undue focus on including all randomised participants can be unhelpful because participants with no post-randomisation data can contribute to the results only through untestable assumptions. The key issue is therefore not how to include all participants but what assumptions about the missing data are most plausibly correct, and how to perform appropriate analyses based on these assumptions. We now expand on these four points.

Strategy for intention to treat analysis with incomplete observations

1. Attempt to follow up all randomised participants, even if they withdraw from allocated treatment

2. Perform a main analysis of all observed data that are valid under a plausible assumption about the missing data

3. Perform sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of departures from the assumption made in the main analysis

4. Account for all randomised participants, at least in the sensitivity analyses

Attempt to follow up all randomised participants

Following up participants who withdraw from randomised treatment can be difficult but is important because they may differ systematically from those who remain on treatment. A trial that does not attempt to follow participants after treatment withdrawal cannot claim to follow the intention to treat principle.

Perform a plausible main analysis

When data are incomplete, all statistical analyses make untestable assumptions. The main analysis should be chosen to be valid under a plausible assumption about the missing data. For example, in the trial in Alzheimer’s disease, consider a group of participants who are lost to follow-up between 6 and 12 months and a group of participants whose outcomes up to 6 months are similar to the first group’s but who are followed at least to 12 months. It may be reasonable to assume in the main analysis that these two groups have similar changes on average from 6 to 12 months—a “missing at random” assumption, under which an analysis of all observed outcome data, with adjustment for selected covariates, is appropriate. A similar assumption underlies standard analyses of time to event data.

Possible analysis methods under a “missing at random” assumption include multiple imputation, inverse probability weighting, and mixed models. These methods, and other methods whose assumptions are less clear, are reviewed elsewhere.9 10

Assumptions about the missing data can often be supported by collecting and reporting suitable information. For example, “missing at random” is often plausible if the reason for most missing data is shown to be administrative error but implausible if the reason is undocumented disease progression.

Perform sensitivity analyses

Good sensitivity analyses directly explore the effect of departures from the assumption made in the main analysis.11 For example, if the main analysis assumes similarity between groups who are and are not lost to follow-up, a good sensitivity analysis might assume that the group who are lost to follow-up have systematically worse outcomes. A clinically plausible amount could be added to or subtracted from imputed outcomes, possibly using a technique such as multiple imputation.9 Conversely, analysts could report how large an amount should be added to or subtracted from imputed outcomes without changing the clinical interpretation of the trial. With a small proportion of missing binary outcomes, best and worst case analyses may be appropriate.12

Results of the sensitivity analyses should be concisely reported in a paper’s abstract, saying, for example, whether the significance of the main analysis was maintained in all sensitivity analyses or was changed in a limited or large number of sensitivity analyses.

Account for all randomised participants in the sensitivity analyses

When sensitivity analyses are carried out in this way, they should account for all randomised participants. For example, if a sensitivity analysis assumes a systematic difference between missing and observed values, then its results directly depend on the extent of missing data in the two trial arms.

Example of strategy in action

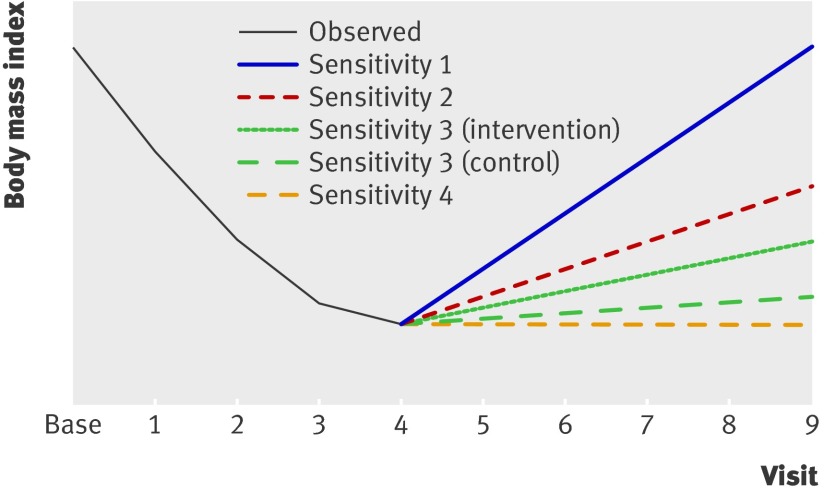

We illustrate the proposed strategy for intention to treat analysis using a recent trial comparing four doses of a new drug for obesity with two control groups.13 Participants had nine planned visits over 20 weeks. The trial report suggests that participants who withdrew from trial treatment were followed up (point 1 of our proposed strategy). The primary analysis (point 2) used last observation carried forward in a “modified intention to treat” population that excluded three participants with no post-randomisation measures. A sensitivity analysis used repeated measures and thus assumed the data were missing at random. Since the main analysis implicitly assumes that participants neither gained nor lost weight on average after loss to follow-up, more direct approaches to sensitivity analysis are preferable. The figure shows our proposals for a hypothetical participant who attends only four of the nine visits (solid line). The red broken line shows the imputed value under last observation carried forward, the study authors’ main analysis, while the other lines show three sensitivity analyses (point 3): sensitivity 1 shows the imputed value assuming that participants lost to follow-up returned to their baseline weight14; sensitivity 2 assumes they regained 50% of their lost weight; and sensitivity 3 assumes a larger fraction of the lost weight was regained in the intervention group.15 Participants with no post-randomisation measures could be included in these analyses by making similar assumptions about their weight gain (point 4).

Fig 1 Possible ways to impute outcome measures at visit 9 for a hypothetical participant in the obesity trial who drops out after visit 4: main analysis (last value brought forward) and three sensitivity analyses (1 assumes participants lost to follow-up return to baseline weight; 2 assumes 50% of weight regained, and 3 assumes intervention group regains a greater proportion of weight than controls)

Discussion

The ideal solution to the problems discussed here is to avoid missing data altogether. This is rarely practical, but missing data can be minimised by careful design and trial management,10 and in particular by attempting to follow up all participants.

The obesity trial illustrated our strategy applied to a trial with a repeatedly measured outcome. Analysis choices are more limited in trials with a singly measured outcome. In trials with time to event outcomes, an analysis that includes all randomised participants with censoring at the point of loss to follow-up is generally acceptable, but possible biases from informative censoring should be considered. In general, primary and sensitivity analyses should be specified in detail, ideally in the registered trial protocol and certainly before the unblinded data are seen, as a defence against claims of data driven changes to the analysis.16

Some argue for conservative analyses.17 However, methods that are conservative in some settings may not be conservative in others. For example, last observation carried forward is often claimed to be conservative, but it can be biased in favour of a new treatment.18 We have instead suggested that authors should make their most plausible assumptions the basis for their primary analysis and then provide conservatism by assessing sensitivity to departures from those assumptions.

Our proposed analysis strategy conforms to the intention to treat principle in the presence of missing outcomes and clarifies uncertainty regarding its application. It acknowledges the uncertainty introduced by missing data and therefore gives investigators an added incentive to minimise the extent of missing data.19 Such guidelines are needed given the importance placed on intention to treat analyses and the ubiquity of missing data in real world clinical trials.

Contributors: IRW had the original idea and wrote the first draft. All authors developed the idea, revised the paper and approved the final version. IRW is guarantor.

Funding: IRW was funded by MRC grant U.1052.00.006, NJH by NIH grant 5R01MH054693-11, and JC by ESRC Research Fellowship RES-063-27-0257.

Competing interests All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; JC has undertaken paid consultancy for various drug companies; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d40

Related links

bmj.com/archive

References

- 1.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peduzzi P, Wittes J, Detre K. Analysis as randomised and the problem of non-adherence: an example from the Veterans Affairs randomized trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Stat Med 1993;12:1185-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman D. Missing outcomes in randomized trials: addressing the dilemma. Open Med 2009;3(2):e51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Points to consider on missing data. 2001. www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/177699EN.pdf.

- 5.Doody R, Gavrilova S, Sano M, Thomas R, Aisen P, Bachurin S, et al. Effect of dimebon on cognition, activities of daily living, behaviour, and global function in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2008;372:207-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackinnon A. Statistical treatment of withdrawal in trials of anti-dementia drugs. Lancet 2008;372:1382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doody R, Seely L, Thomas R, Sano M, Aisen P. Authors’ reply. Lancet 2008;372:1383.18940461 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter JR, Kenward MG. Missing data in clinical trials — a practical guide. Birmingham: National Institute for Health Research, 2008. www.pcpoh.bham.ac.uk/publichealth/methodology/projects/RM03_JH17_MK.shtml.

- 10.National Research Council. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. 2010. www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12955. [PubMed]

- 11.Kenward MG, Goetghebeur EJT, Molenberghs G. Sensitivity analysis for incomplete categorical tables. Stat Model 2001;50:15-29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollis S. A graphical sensitivity analysis for clinical trials with non-ignorable missing binary outcome. Stat Med 2002;21:3823-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astrup A, Rössner S, Van Gaal L, Rissanen A, Niskanen L, Al Hakim M, et al. Effects of liraglutide in the treatment of obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2009;374:1606-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JH. Interpreting incomplete data in studies of diet and weight loss. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White IR, Carpenter J, Evans S, Schroter S. Eliciting and using expert opinions about non-response bias in randomised controlled trials. Clin Trials 2007;4:125-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shih WJ. Problems in dealing with missing data and informative censoring in clinical trials. Curr Contr Trials Cardiovasc Med 2002;3:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on missing data in confirmatory clinical trials. 2010. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2010/09/WC500096793.pdf.

- 18.Siddiqui O, Hung HM, O’Neill R. MMRM vs. LOCF: a comprehensive comparison based on simulation study and 25 NDA datasets. J Biopharm Stat 2009;19:227-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittes J. Missing inaction: preventing missing outcome data in randomized clinical trials. J Biopharm Stat 2009;19:957-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]