Abstract

Controlled proteolysis mediated by Smad ubiquitination regulatory factors (Smurfs) plays a crucial role in modulating cellular responses to signaling of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily. However, it is not clear what influences the selectivity of Smurfs in the individual signaling pathway, nor is it clear the biological function of Smurfs in vivo. Using a mouse C2C12 myoblast cell differentiation system, which is subject to control by both TGF-β and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), here we examine the role of Smurf1 in myogenic differentiation. We show that increased expression of Smurf1 promotes myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells and blocks the BMP-induced osteogenic conversion but has no effect on the TGF-β-induced differentiation arrest. Consistent with an inhibitory role in the BMP signaling pathway, the elevated Smurf1 markedly reduces the level of endogenous Smad5, whereas it leaves unaltered that of Smad2, Smad3, and Smad7, which are components of the TGF-β pathway. Adding back Smad5 from a different source to the Smurf1-over-expressing cells restores the BMP-mediated osteoblast conversion. Finally, by depletion of the endogenous Smurf1 through small interfering RNA-mediated RNA interference, we demonstrate that Smurf1 is required for the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells and plays an important regulatory role in the BMP-2-mediated osteoblast conversion.

Smad proteins are principal intracellular signaling mediators of the TGF-β1 superfamily of peptide growth factors that regulate a wide range of biological processes (1–3). As such, controlling Smad activity and protein levels are crucial for proper signaling by TGF-β and its related factors. Recent discoveries of Smad ubiquitination regulatory factors (Smurfs), which are members of the HECT domain family of ubiquitin ligases, have implicated a role of the ubiquitination-mediated protein degradation in the signaling pathways of TGF-β superfamily (4–7). Ubiquitination is a covalent attachment of a chain of the highly conserved, 76-amino acid ubiquitin to selected targets, which are subsequently degraded in the 26 S proteasomes (8, 9). This process is catalyzed by sequential actions of three enzymes, the E1 ubiquitin activating enzyme, the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and the E3 ubiquitin ligase. Ubiquitin ligases physically interact with protein substrates, therefore playing a central role in determining substrate specificity. Despite several reports of biochemical evidence for the Smurf-mediated degradation of Smads, important questions remain with regard to the biological significance of this regulation and the specificity of Smurf action.

Signaling by the TGF-β superfamily of peptide growth factors is mediated by a complex of two types of transmembrane serine/threonine kinase receptors and the intracellular Smad proteins (for reviews, see Refs. 1–3). Three classes of Smads have been defined based on their differences in sequence and function: the receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads), the common Smad (Smad4), and the inhibitory Smads (I-Smads). Within the ligand-activated receptor complex, R-Smads physically interact with and are phosphorylated at their C terminus by type I receptors. This results in association between the activated R-Smads and Smad4, and the nuclear accumulation of the R-Smad·Smad4 complex. In the nucleus, the R-Smad·Smad4 complex modulates transcription in conjunction with a variety of DNA-binding partners. Different sub-groups of R-Smads mediate signaling of different ligands and their respective receptors. For instance, Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 are phosphorylated by the activated BMP type I receptor and mediate BMP responses, whereas Smad2 and Smad3 are phosphorylated by the type I receptors of both TGF-β and activin, and are responsible for transducing signal from either of these two ligands. Likewise, I-Smads, which negatively regulate TGF-β superfamily signaling by stably interacting with the type I receptor, also display ligand preference. Between the two I-Smads that are currently known, Smad6 specifically inhibits BMP signaling whereas Smad7 primarily inhibits signaling of TGF-β and activin.

Smurfs are identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for proteins that bind Smad1 and through searching the expressed sequence tag data base for Smurf homologous sequences (4–7). Both Smurf1 and Smurf2 have been shown to act upon R-Smads, with Smurf1 specifically interacting with Smad1 and Smad5 (4), the R-Smads specific to the BMP pathway, and Smurf2 interacting more promiscuously with Smad1, Smad2, Smad3 and Smad5 (5, 7). The activities of Smurf1 and Smurf2 appear to be unregulated by the receptor-mediated phosphorylation of R-Smads (4, 7). However, recent studies have unraveled a second activity of Smurfs, which does require ligand activation: both Smurf1 and Smurf2 have been shown to interact with the inhibitory Smad7 and use it as an adaptor for the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of the activated TGF-β receptors (6, 10). Similar mechanism has been proposed for the TGF-β-induced destruction of SnoN, which involves formation of a Smad2·Smurf2 complex (11). Thus, Smurf1 and Smurf2 regulate TGF-β and BMP signaling with different underlying mechanisms.

To address the biological significance of Smurf-mediated Smad degradation and the specificity of Smurfs toward TGF-β or BMP signaling, we took advantage of the in vitro differentiation of C2C12 myoblast cells. C2C12 cells were originally isolated from injured adult mouse muscle and have proven an excellent model system in which to study myogenic differentiation (12, 13). C2C12 cells proliferate in regular culture medium, but undergo terminal differentiation when grown to confluence and deprived of growth factors. During this process, C2C12 cells exit cell cycle, up-regulate muscle-specific genes, and fuse into multinucleated myotubes. Both TGF-β and BMP inhibit the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts, but the outcomes of inhibition by these two factors are very different. Although treating C2C12 cells with TGF-β simply arrests the cells in an undifferentiated state, treating with BMP forces the cells into an alternate osteogenic pathway characterized in part by up-regulation of genes associated with osteoblast phenotype such as alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin (14–17). Here we report that overexpression of Smurf1 in C2C12 myoblasts blocks the BMP-induced osteogenic conversion but has little impact on the ability of TGF-β to inhibit the myogenic differentiation. We also show that the specific effect of Smurf1 in BMP signaling is accounted for by the degradation of Smad5. Finally, using small interfering RNA (siRNA) to knock down endogenous Smurf1 in C2C12 cells, we demonstrate that, at the physiological level, Smurf1 is required for myogenic differentiation and does operate in C2C12 cells to modulate BMP-mediated osteogenic differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Induction of Myogenic Differentiation

The C2C12 line of mouse myoblasts was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). For routine maintenance, C2C12 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin-G and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2. To initiate myogenic differentiation, C2C12 cells were first grown to 80% confluency in the regular culture growth medium (GM) before they were switched to a differentiation medium (DM) consisting of DMEM, 2% horse serum, and antibiotics.

Construction of Stable C2C12 Cell Lines Overexpressing Smurf1

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer was used to establish stable lines of C2C12 cells that overexpress Smurf1. Human Smurf1 cDNA containing a copy of FLAG epitope at its N terminus was subcloned into BamHI and SalI sites of the retroviral expression vector, pBABEpuro (18). The expression vector was transfected into Phoenix E packaging cells for viral production. Infectious viral particles were collected from the culture medium 2 days following transfection as described previously (19). Infection was carried out in 6-well plates that were seeded with 1 × 105 cells/well on the previous day. Each well was overlaid with 1 ml of an equal mix of 15% FBS in DMEM and the viral supernatant in the presence of 4 μg/ml Polybrene for 5 h, then replaced with fresh medium. Puromycin was added at 2 μg/ml to the culture medium 48 h after infection to select for infected cells. Puromycin-resistant clones were isolated from serial dilutions of the infected cells.

Expression Plasmids and siRNA

Expression plasmids for N-terminal hemagglutinin-tagged Smad1 and FLAG-tagged Smad2 were described before (7, 20). FLAG-tagged Smurf1 (10) were obtained from Dr. K. Miyozono (University of Tokyo). The N-terminal FLAG-tagged Smad5 was constructed from the mouse Smad5 cDNA (a gift from Dr. X.-F. Wang, Duke University) and subcloned between the BamHI and SalI sites of pRK5-FLAG (7).

Mouse Smurf1 siRNA duplex with a fluorescein label at the 3′-end of sense strand was synthesized by Qiagen-Xeragon (Germantown, MD). The sense strand sequence of Smurf1 siRNA is CCUUGCAAAGAAA-GACUUCdTdT. The non-silencing siRNA from Qiagen, which does not target any known mammalian gene, was used as the negative control. SiRNA transfection of C2C12 cells was carried out using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) in 12-well plates (120 pmol per well) as described before (21). After transfection, cells were recovered in the regular growth medium for 48 h before being induced to differentiate in the differentiation medium. The transfection efficiency of siRNA was determined by measuring fluorescence intensity of the trypsinized cells using flow cytometry.

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assay

Transient transfection of C2C12 cells was carried out using LipofectAMINE (Invitrogen) in 6-well plates. Briefly, 3 × 105 cells/well were plated 1 day prior to transfection, and 1 μg of expression plasmid was used per transfection. For luciferase assay, in each DNA sample, 50 ng of control luciferase vector (pRL-TK) was included as an internal control for transfection efficiency, and 0.5 μg of skeletal actin promoter-luciferase vector (22) was used as the transcription readout. 0.5 μg of Smad expression plasmid or 30 pmol of siRNA were co-transfected with reporter constructs. Six hours after transfection, cells were set to recover in the regular growth medium (15% FBS in DMEM) overnight. The luciferase activity was determined by Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) after culturing for 2 days in differentiation medium. Results were obtained from at least two independent experiments with triplicate samples for each data point.

Antibodies, Protein, and RNA Blot Analyses

Cells were lysed in whole cell lysis buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, containing 300 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EGTA, 20% glycerol, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors) by two freeze-thaw cycles between liquid nitrogen and ice. After clearing out cell debris by centrifugation, 30 μg of total protein was loaded onto each lane of a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and subjected to Western blot analysis. The antibodies used were rabbit anti-myogenin polyclonal antibody (M-225, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), rabbit anti-Smad1 polyclonal antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc.), goat anti-Smad5 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-Smad2 monoclonal antibody (Upstate), rabbit anti-Smad3 polyclonal antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc.), rabbit anti-Smad7 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (Biodesign), and anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma). Rabbit anti-phospho-Smad2 (23) and anti-phospho-Smad3 (24) antibodies were general gifts from Drs. C.-H. Heldin and P. ten Dijke, and Dr. M. Reiss, respectively.

Anti-Smurf antiserum was raised by immunization of rabbits with a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein containing amino acid residues 248–369 of human Smurf2. This fusion protein contains the human Smurf2 WW2 and WW3 domains, which are identical to the corresponding region of mouse Smurf2 and over 80% identical to that of human and mouse Smurf1. Western blot analysis indicated that the antiserum (1/1000 dilution) recognized both human and murine Smurf1 and Smurf2 (data not shown).

For RNA blot analysis, total RNA was isolated from differentiating cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). 20 μg of RNA was resolved on a 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gel, blotted to an Immobilon-NY+ membrane (Millipore), and hybridized to cDNA probes that were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3000 ci/mmol, New Life Sciences) using a random labeling kit, Prime-It RmT (Stratagene). The cDNA probe for mouse osteocalcin (25) was provided by Dr. C. X. Deng (NIDDK, National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence Staining and Microscopic Analyses

To monitor the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells, serial images of differentiating cells were taken with a phase-contrast microscope at a 1-day interval after switching to the differentiation medium. For TGF-β and BMP treatment, the ligands were added along with the differentiation medium. Immunofluorescence staining of myosin heavy chain (MHC) was carried out in two-chamber slides. The slides were fixed and permeabilized in PBS containing 3.7% formaldehyde and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min, and blocked in PBS containing 2 mg/ml BSA for 30 min. The cells were stained with MY-32 (monoclonal anti-MHC, Sigma) (1:40) as the primary antibody and the Oregon Green-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) before visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

Alkaline Phosphatase Assay

Histochemical detection of the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was performed on cells that were fixed for 10 min in 3.7% formaldehyde at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated for 30 min in a mixture of 0.1 mg/ml Naphthol AS-MX phosphate (Sigma), 0.5% N,N-dimethylformamide, 2 mm MgCl2, and 0.6 mg/ml of fast blue BB salt (Sigma) in 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, at room temperature, followed by observation under microscope. For quantitative analysis of ALP activities, cells were lysed in PBS, 0.01% SDS. After clarification by centrifugation, equal volumes of cell lysates were analyzed for ALP activity using an ALP assay kit (Sigma Diagnostics). The colorimetric reactions, executed in the linear range, were stopped by addition of 0.05 m NaOH, and the absorbance was measured at 420 nm. Background absorbance (assessed spectrophotometrically after addition of HCl) was subtracted from the total value. Phosphatase activities were expressed as micromoles of p-nitrophenol produced per minute per milligram of protein. Total protein content was determined by BCA assay using BSA as the standard.

Creatine Kinase Assay

C2C12 cells grown in 12-well plates were washed twice in cold PBS and scraped from the plates in 100 μl of PBS. After sonication with two 30-s bursts at 4 °C, the cells were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. A CK-NAC kit (Roche Applied Science) was used to measure creatine kinase activity. Briefly, 50 μl of the above supernatant was mixed with 1 ml of reaction buffer and incubated for 3 min at room temperature, then optical density reading at 340 nm were recorded at 1-min intervals over a period of 3 min. The creatine kinase activity was expressed as units over protein concentration, which was determined by BCA assay using BSA as the standard.

TGF-β Receptor Affinity Labeling

To detect the endogenous TGF-β receptors, subconfluent cells were washed on ice with KBB buffer (120 mm NaCl, 4.8 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 5 mm MgSO4, 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.5% BSA). 125I-TGF-β1 (50 pm) was added to the washed cells in KBB and incubated for 4 h at 4 °C. Surface-bound 125I-TGF-β1 was cross-linked to the receptors as described previously (26). Cell lysates with equal protein content were resolved by 10% SDS gel, and the ligand-receptor complex was examined by autoradiography.

Adenovirus Infection

Recombinant adenoviruses, Ad.β-galactosidase and Ad.Smad5 (27), were kindly provided by Drs. M. Fijii and A. Roberts (NCI, National Institutes of Health). Infection of C2C12 cells was conducted as described (27). After infection, cells were recovered in the regular culture medium for 12 h before being induced to differentiate in the differentiation medium.

RESULTS

Smurf1 Promotes Myogenic Differentiation

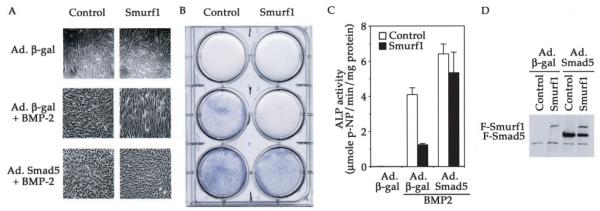

To assess the function of Smurf1 in myogenic differentiation, we infected C2C12 cells with either an empty retroviral vector as control or a recombinant virus that expresses the N-terminal FLAG-tagged Smurf1. Stable clones were isolated from the infected cell population; two of the clones (clone 1 and clone 6) expressing high level of FLAG-Smurf1 were selected for further analyses (Fig. 1, upper panel). A rabbit polyclonal antiserum that was raised against the amino acid residues 248–369 of human Smurf2 recognizes both Smurf1 and Smurf2 of the human or murine origin (data not shown). Using this antiserum, we demonstrated that the total level of Smurf proteins in both clone 1 and clone 6 cells was markedly increased relative to that in control cells infected with vector virus (Fig. 1, bottom panel), due to the expression of the exogenous FLAG-Smurf1.

Fig. 1. Elevated expression of Smurf1 in stably transfected C2C12 cells.

Lysates (30 μg of total protein) of stable clones of C2C12 cells, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, were analyzed by Western blot using anti-FLAG antibody for the FLAG-tagged Smurf1 (top panel) and anti-Smurf antiserum for total Smurf proteins (bottom panel). Clones 1 and 6: two independent isolates derived from the Smurf1 virus-infected cell population; Control: a pool of the vector virus-infected cells. A nonspecific band in C2C12 cell lysates is indicated by an asterisk.

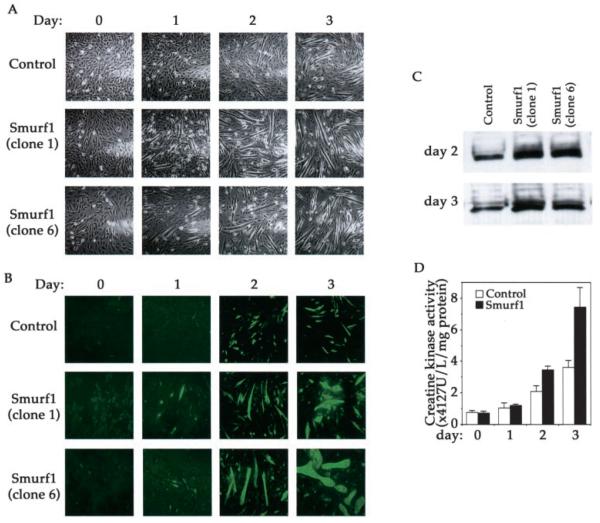

Having established the stable clones of C2C12 cells that overexpress Smurf1, we examined the impact of elevated Smurf1 on myogenic differentiation. As with the non-infected wild type C2C12 cells, the stable cells harboring empty control vector adopted an appearance of multinucleated myotube 2–3 days after they were cultured in the differentiation medium (Fig. 2A, upper panels and data not shown). This differentiation process, however, was accelerated in both Smurf1-overexpressing clones, which began to differentiate on as early as the first day after culturing in the differentiation medium (Fig. 2A, middle and bottom panels). Moreover, the myotubes seen in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells appeared larger than those in the vector virus infected control cells (Fig. 2A). The difference in morphological appearance seen under the phase-contrast microscope was corroborated by immunofluorescence staining of the muscle-specific protein, myosin heavy chain (MHC): in the differentiation medium, the number of MHC-positive cells in the Smurf1-overexpressing cell population was higher, and the size of the positive cells was generally larger than those in the control cells (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the accelerated myogenic differentiation, myogenin, an early molecular maker of myogenic differentiation (28–30), was induced to a higher extent in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells than in the control cells (Fig. 2C). To quantify the extent to which C2C12 cells differentiate into myotubes, we measured the activity of creatine kinase, which is specifically associated with muscle differentiation (14, 15). In the differentiation medium, the creatine kinase activity of the vector-infected control cells gradually increased, however, the rate of the increase was more rapid in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells (Fig. 2D): by the third day of culturing in the differentiation medium, the level of creatine kinase activity was higher in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells than that in the control cells. The above results taken together indicate that Smurf1 facilitates myogenic differentiation. However, overexpressing Smurf1 per se is not sufficient to induce myogenic differentiation, because no myotubes nor increased creatine kinase activity was detected in the above stable C2C12 clones when they were cultured in the regular growth medium (Fig. 2, A, B, and D, day 0 panels).

Fig. 2. Smurf1 promotes myogenic differentiation.

A, phase-contrast microscopic images of the vector-infected control and the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells. The photographs were taken on the indicated day after the cells were incubated in the differentiation medium. B, immunofluorescence staining of myosin heavy chain (MHC). C, Western blot analysis of endogenous myogenin in differentiating C2C12 cells. An equal amount of total protein (30 μg) was loaded in each lane. D, creatine kinase activities in vector control and the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells after culturing in the differentiation medium for the indicated days. Both clone 1 and clone 6 of the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells exhibited the similar increase in creatine kinase activity, but only results from clone 1 were shown. Each data point represents results obtained from at least two independent experiments with triplicate samples.

Overexpression of Smurf1 Does Not Affect the TGF-β-induced Inhibition of Myogenic Differentiation But Blocks the BMP-mediated Osteoblast Conversion

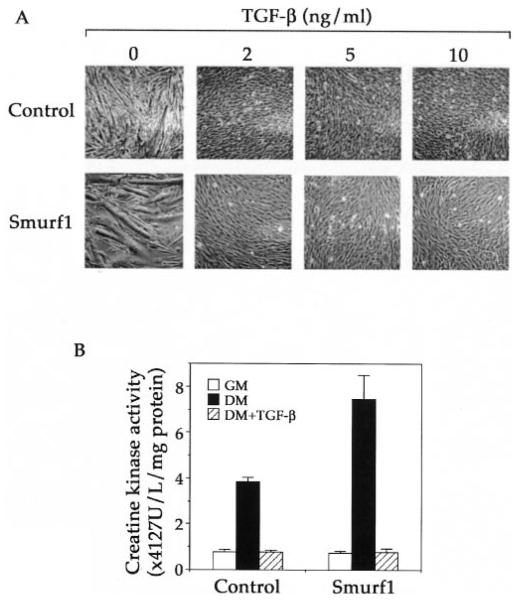

Because both TGF-β and BMP inhibit myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells but with different morphological outcomes, we began our analyses of the effect of overexpressing Smurf1 over TGF-β or BMP treatment by simply following the changes in cell appearance. As shown previously, switching either the vector-infected control or the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells to differentiation medium effectively turned on the myogenic differentiation program as indicted by the formation of myotube fusion (Fig. 3A, left-most panels). In the presence of TGF-β, however, the myogenic differentiation of both control and Smurf1-overexpressing cells was completely blocked regardless of the presence of exogenous Smurf1 (Fig. 3A). Likewise, treating cells with 5 ng/ml TGF-β also diminished the creatine kinase activity in both control and Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Smurf1 does not affect TGF-β-induced inhibition of the myogenic differentiation.

A, phase-contrast microscopic images of the vector-infected control and the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells taken 3 days after culturing in the differentiation medium in the absence or presence of the indicated amount of TGF-β. Both clone 1 and clone 6 of the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells exhibited the similar response to TGF-β, but only representative results from clone 6 are shown. B, creatine kinase activities of the vector-infected control and the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells. Experiments were done the same as in Fig. 2D, except that the cells were cultured either in the growth medium (GM) or differentiation medium (DM) in the absence or presence of TGF-β (5 ng/ml) for 3 days.

In contrast to the lack of effect on TGF-β treatment, overexpression of Smurf1 completely reversed the BMP-induced osteogenic conversion of C2C12 myoblasts. In the differentiation medium, treatment of BMP-2 inhibited myotube formation in control cells (Fig. 4A, top panels). In addition, BMP-2 treatment further diverted these cells into osteoblast differentiation, as evidenced by the up-regulation of alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 4B) and osteocalcin expression (Fig. 4C), two specific markers of osteoblasts. Under the same conditions, however, myogenic differentiation continued unabatedly in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells, even in the presence of up to 300 ng/ml BMP-2 (Fig. 4A, lower panels). Moreover, BMP-2-induced alkaline phosphatase activity and osteocalcin expression was also inhibited in these Smurf1-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4, B and C). Thus, these results indicate that overexpression of Smurf1 specifically inhibits the BMP signaling while having no impact on the TGF-β signaling.

Fig. 4. Smurf1 blocks the BMP-mediated osteoblast conversion.

A, phase-contrast microscopic images taken after the cells were cultured in the differentiation medium with indicated concentration of BMP-2 for 3 days. Both clone 1 and clone 6 of the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells exhibited the similar response to BMP-2, but only representative results from clone 6 are shown. B, quantification of the alkaline phosphatase activity in vector-infected control and Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells. Experiments were done the same way as in A. C, Northern blot analysis of osteocalcin mRNA isolated from vector-infected control or Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells after culturing in the differentiation medium with or without BMP-2 (300 ng/ml) for 3 days. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA was used as a loading control.

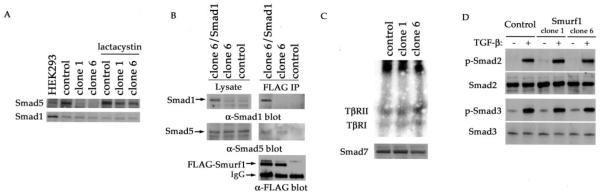

Overexpression of Smurf1 Decreases the Steady-state Level of Smad5

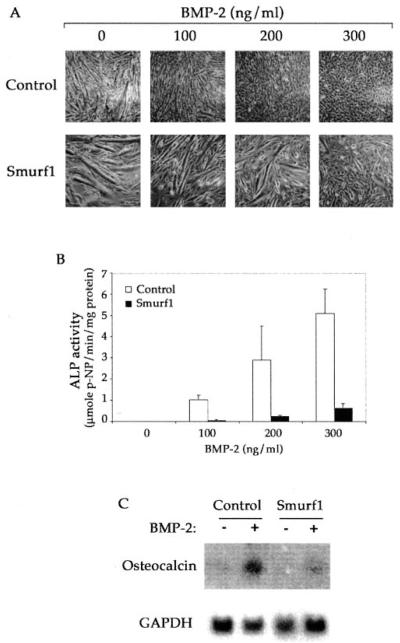

To gain an insight into the molecular mechanism by which ectopic expression of Smurf1 influences the effect of TGF-β or BMP on myogenic differentiation, we sought the effect of elevated Smurf1 on the level of Smads, the intracellular signaling transducers of the TGF-β superfamily. Previous studies have shown that Smurf1 interacts with Smad1 and Smad5, the R-Smads of the BMP pathway, and targets them to ubiquitination and the subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation (4). Consistent with these findings, overexpression of Smurf1 dramatically decreased the level of endogenous Smad5 (Fig. 5A). The reduction in the level of Smad5 was reversed by the treatment of lactacystin, a known proteasome inhibitor, indicating that the reduction was due to the proteasome-mediated protein degradation. Surprisingly, overexpression of Smurf1 had little effect on the level of endogenous Smad1 (Fig. 5A), a closely related homologue of Smad5. This unexpected insensitivity of Smad1 to Smurf1 overexpression may result from another layer of as yet to be resolved regulation, or alternatively, a requirement of threshold protein level in the Smurf-mediated degradation. As shown in Fig. 5A, the level of endogenous Smad1 was already at an extremely low level in C2C12 cells relative to that in other cells, e.g. HEK293 cells (compare the ratio between Smad1 and Smad5 in these two cells).

Fig. 5. Effects of Smurf1 overexpression on various signaling components of the TGF-β or BMP pathway in C2C12 cells.

A, steady-state levels of endogenous Smad1 or Smad5 determined by Western blot analysis using specific anti-Smad1 or anti-Smad5 antibodies. The reduction of Smad5 in clone 1 and clone 6 was reversed by the addition of lactacystin (20 μm) for overnight. The ratio between Smad1 and Smad5 indicates that Smad1 was expressed at much lower level in C2C12 cells than that in HEK293 cells. B, physical interaction among the stably expressed FLAG-Smurf1 and the endogenous Smad5, or transfected Smad1 but not endogenous Smad1 in C2C12 cells. To capture the Smurf1 and Smad interaction, cells were treated with lactacystin (20 μm) for overnight before they were lysed and subjected to anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation, followed by anti-Smad1 (right, top panel) or anti-Smad5 (right, middle panel) immunoblot analyses to detect the co-precipitated Smad1 or Smad5, respectively. The level of FLAG-Smurf1 in the immunoprecipitates (right, bottom panel) and Smad1 or Smad5 in the total cell lysates (left panel) are shown as indicated. C, effect of Smurf1 overexpression on cell surface TGF-β receptor and endogenous Smad7. The amount of cell surface TGF-β receptors was assessed by [125I]TGF-β labeling and autoradiography (top panel). Western analysis of total cell lysates using anti-Smad7 antibody is shown in the bottom panels. D, phosphorylation status of Smad2 and Smad3 in vector control and Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells after treating with 5 ng/ml TGF-β for 1 h. Phosphorylated or total Smad2 or Smad3 were detected using anti-phospho-Smad2, anti-Smad2, anti-phospho-Smad3, and anti-Smad3 antibodies.

To further address the mechanism of Smurf1-mediated degradation of Smad5, we examined the physical interaction between the exogenously expressed Smurf1 and the endogenous Smad1 or Smad5. We immunoprecipitated the FLAG-tagged Smurf1 from cell lysates of the Smurf1-overexpressing cells (clone 6) or the vector control cells, and found that only the endogenous Smad5 co-precipitated with FLAG-Smurf1 (Fig. 5B, middle panels). The endogenous Smad1 did not co-precipitate with FLAG-Smurf1 (Fig. 5B, top panels). To distinguish if the apparent lack of interaction between Smurf1 and Smad1 was due to decreased Smad1 production in C2C12 cells or an unknown regulatory mechanism, we boosted the level of Smad1 by introducing a Smad1 expression plasmid. At the augmented level of Smad1 expression, interaction between Smurf1 and Smad1 was readily detectable (Fig. 5B).

In addition to Smad1 and Smad5, Smurf1 also reportedly interacts with Smad7, an inhibitory Smad of the TGF-β pathway, and uses Smad7 as an adaptor to promote turnover of the TGF-β receptors (10). We therefore analyzed the effects of overexpression of Smurf1 on the levels of cell surface TGF-β receptors, Smad7, and other relevant components of the TGF-β pathway. As shown in Fig. 5C, cell surface [125I]TGF-β1 affinity-labeled receptors levels in vector-control and Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells were comparable (top panel). In addition, the protein level of endogenous Smad7 was also not affected by ectopic expression of Smurf1 (Fig. 5C, bottom panels) as illustrated by immunoblot analyses of cell lysates. We also evaluate the TGF-β-stimulated Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation, because they reflect the activity of the receptor kinases in the cytoplasm (31). As shown in Fig. 5D, Smad2 and Smad3 protein levels and TGF-β-mediated Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation were not affected by Smurf1 expression in C2C12 cells either. This is in agreement with the earlier observation that the TGF-β-mediated inhibition of myotube formation was unaffected by the ectopic expression of Smurf1. These results indicate that the elevated Smurf1 in C2C12 cells specifically targets Smad5 for the ubiquitin-mediated degradation, and thereby blocks the BMP-mediated osteogenic conversion.

Super-infection of the Smurf1-overexpressing Cells with Smad5 Arrests the Myogenic Differentiation and Restores the BMP-2-induced Osteoblast Conversion

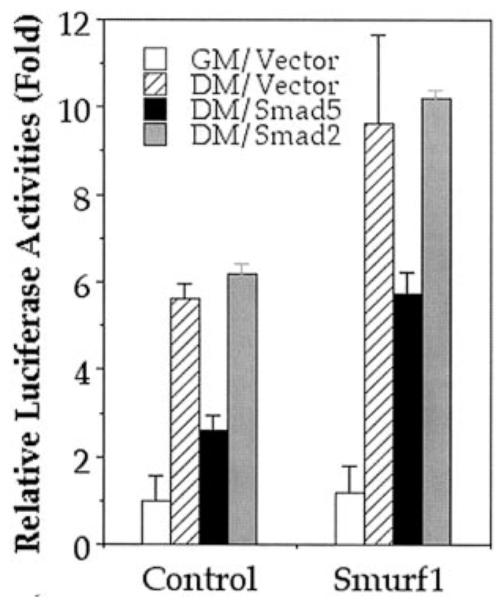

To determine if the accelerated myogenic differentiation and the cessation of BMP-induced osteogenic conversion in Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells were indeed resulted from reduction of Smad5 protein level, we tested if these changes can be reversed by adding back Smad5 from a different source. Because of the difficulty associated with generating stable cells with two different selection markers, we used transient transfection to introduce Smad5 into the established stable cells and monitored the effect of these Smad proteins on a skeletal actin promoter driven transcription reporter assay that has been used as a surrogate indicator of myogenic differentiation (22). In the absence of transfected Smad, this skeletal actin reporter exhibited a higher activity in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells than in the vector-infected control cells after switching to the differentiation medium (Fig. 6, 9- to 10-fold versus 5-fold increase relative to the basal level in the regular growth medium). However, co-transfection of Smad5 together with the skeletal actin reporter caused a significant reduction of the reporter activity in either the Smurf1-overexpressing cells or the control cells (Fig. 6, 5- to 6-fold versus 2.5-fold increase relative to the basal level). In contrast, co-transfection of Smad2 had no such effect in either type of cells.

Fig. 6. Specific inhibition of the skeletal actin promoter reporter by Smad5.

Vector control and Smurf1-expressing C2C12 cells were transiently transfected with empty vector, Smad5, or Smad2 expression vectors as indicated. The expression of luciferase activity powered by the skeletal actin promoter was measured 2 days after the transfected cells were incubated in the differentiation medium (DM). The relative luciferase activity is expressed as the ratio to the luciferase readout in vector-transfected control C2C12 cells maintained in the regular culture growth medium (GM).

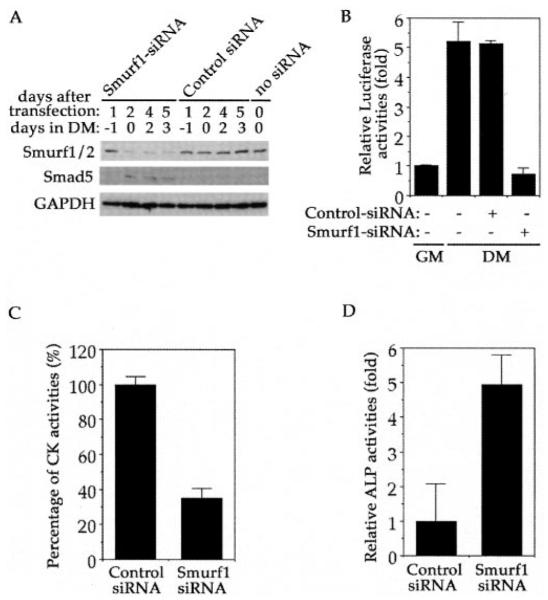

To test if adding back Smad5 restores the BMP-induced osteogenic conversion in Smurf1-overexpressing cells, we super-infected these cells with recombinant adenoviruses carrying either a copy of the FLAG-tagged Smad5 cDNA (Ad.Smad5) or the β-galactosidase cDNA (Ad.β-galactosidase) as a control (27). Under our experimental conditions, ~80–90% of the cells became infected as determined by staining for β-galactosidase following infection with the control Ad.β-galactosidase virus (27; data not shown). Super-infection by adenovirus itself exerted little effect over the myogenic differentiation, because the myotubes formed in either control or Smurf1-overexpressing cells infected with Ad.β-galactosidase virus appeared very similar in both shape and size to those in cells that were not infected with adenovirus (Fig. 7A, top panels and previous figures). This indicates that the adenovirus gene delivery system does not alter the morphological or differentiation characteristics of C2C12 cells. Super-infection by adenovirus also did not affect the BMP-2-induced osteoblast conversion in the control cells that do not express FLAG-Smurf1 or alter the effect of Smurf1 over the BMP-2-mediated inhibition of myogenic differentiation (Fig. 7A, middle panels). However, super-infection by Ad.Smad5 virus, which produced additional amount of Smad5 in the infected cells (Fig. 7D), negated the myogenic promoting effect of Smurf1 and restored the ability of BMP-2 to induce the osteoblast conversion of C2C12 cells (Fig. 7, A and B, lower panels, and Fig. 7C). Taken together, the above results demonstrate that reduction of Smad5 protein level in the Smurf1-overexpressing cells is the principal cause that diminishes the ability of such cells to respond to BMP signaling, leading to an accelerated myogenic differentiation and the concurrent inability to undergo BMP-induced osteoblast conversion.

Fig. 7. Super-infection of Smurf1-expressing cells with Smad5 arrests the myogenic differentiation and restores the BMP-induced osteoblast conversion.

Vector control or Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells were infected with adenovirus expressing either β-galactosidase or FLAG-Smad5. After infection, cells were recovered in DMEM containing 15% FBS for 12 h followed by incubation in the differentiation medium for 3 days. A, phase-contrast images of the adenovirus-infected vector control or Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells taken 3 days after the cells were incubated in the differentiation medium without (top panel) or with 300 ng/ml BMP-2 (middle and bottom panels). B, histochemical analysis of alkaline phosphatase activities of the cells from A. C, quantification of the alkaline phosphatase activities. The cells were treated the same as in A. D, expression of super-infected FLAG-Smad5 in vector control or Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells. Total cell lysates were prepared 12 h after infection and subjected to the Western blot analysis using anti-FLAG antibodies.

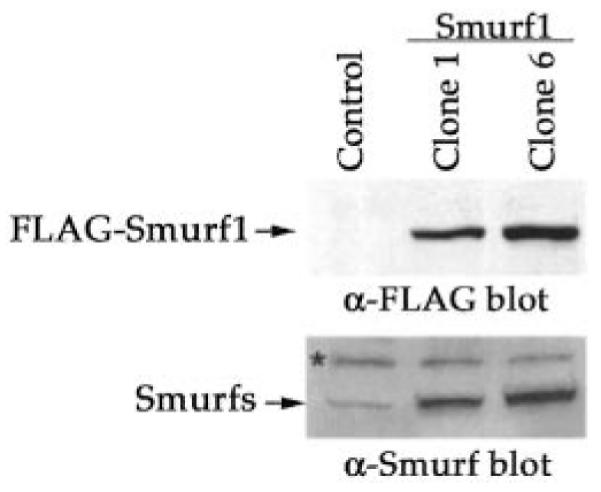

Role of Smurf1 in Myogenic and Osteoblast Differentiation

To determine if Smurf1 indeed operates in C2C12 cells to regulate the myogenic differentiation, we knocked down the expression of endogenous Smurf1 through siRNA-mediated RNA interference. Using a fluorescein-labeled siRNA specifically targeting Smurf1, we isolated the siRNA-transfected cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting and found that the total level of Smurfs was reduced by at least 50% 2 days after transfection (Fig. 8A). Because the anti-Smurf antiserum used for this determination recognizes both Smurf1 and Smurf2, the actual percentage of Smurf1 reduction could be even greater. The expression of Smurf1 remained low for at least 5 days after transfection of the specific Smurf1-siRNA, but the non-silencing control siRNA had no such effect (Fig. 8A). Concurrent with Smurf1 protein reduction, the level of endogenous Smad5 protein was significantly increased, lending further evidence that Smad5 is subject to the Smurf1-mediated proteolytic control through ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. To quantify the effect of Smurf1-siRNA-mediated RNA interference on myogenic differentiation and the BMP-induced osteogenic conversion, we assayed transcription of skeletal actin promoter-driven reporter as well as the creatine kinase activity and alkaline phosphatase activity in the transfected C2C12 cells. After switching to the differentiation medium, the cells that received no siRNA or control non-silencing siRNA displayed an elevated skeletal actin promoter activity, but such induction was not observed in the cells that received the Smurf1-siRNA (Fig. 8B). Similarly, the induction of creatine kinase observed in the control siRNA-transfected cells was also decreased dramatically in the Smurf1-siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 8C), indicating that Smurf1 is required for the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. Finally, knocking down Smurf1 expression in the BMP2-treated C2C12 cells augmented the BMP-induced osteoblast conversion as evident by the increased alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 8D). Therefore, Smurf1 does play a physiological role in the myogenic differentiation and the BMP-mediated osteoblast conversion in C2C12 cells.

Fig. 8. Requirement of Smurf1 during myogenic differentiation and its role in the BMP-mediated osteoblast differentiation in C2C12 cells.

A, Smurf1-siRNA, but not a control siRNA, reduced the protein level of Smurf (top panel) but increased the amount of Smad5 (middle panel). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase protein level was not affected by Smurf1-siRNA (bottom panel). B, specific inhibition of the skeletal actin promoter activity by the Smurf1-siRNA. Smurf1-siRNA, but not a control siRNA, inhibited transcription activation from skeletal actin promoter. The luciferase activity was measured 2 days after culturing the transfected cells in the differentiation medium (DM) following overnight recovery in regular growth medium. The relative luciferase activity is expressed as the ratio to the luciferase readout in reporter plasmid-transfected C2C12 cells maintained in the regular culture growth medium (GM). C, inhibition of creatine kinase activity by Smurf1-siRNA. Fluorescein-labeled Smurf1-siRNA or control siRNA was transfected into C2C12 cells, and creatine kinase activities were measured after the transfected cells were incubated in the differentiation medium for 3 days. Kinase activities were normalized to transfection efficiency measured using flow cytometry. D, augmentation of the alkaline phosphatase activity by Smurf1-siRNA. Alkaline phosphatase activities were measured in C2C12 cells transfected with either fluorescein-labeled Smurf1-siRNA or control siRNA and incubated in differentiation medium for 3 days in the presence of 200 ng/ml BMP-2. The activities were normalized to transfection efficiency measured using flow cytometry. The relative activity was expressed as the -fold relative to the alkaline phosphatase activity in control siRNA-transfected cells.

DISCUSSION

When grown to confluence and deprived of growth factors, C2C12 cells spontaneously commit to a myogenic differentiation process that can be blocked by the action of both TGF-β and BMP (14–17, 27, 30). Because treating the differentiating C2C12 cells with TGF-β or BMP gives rise to two distinct sets of easily discernible phenotypic outcomes, this in vitro differentiation process offers a very useful model system for examining the specificity of regulatory factors toward TGF-β or BMP signaling. In this study, we infected C2C12 cells with a retrovirus that expresses Smurf1 and examined the influence of the elevated Smurf1 over cellular response to TGF-β or BMP. Our data show that an increase in the Smurf1 expression blocks the BMP-induced conversion of C2C12 myoblasts to osteoblasts. In contrast, Smurf1 expression does not block the inhibitory effect of TGF-β on myogenic differentiation. Concurrent with the blocking activity of Smurf1 on the BMP-induced osteoblast differentiation, we also observed a significant reduction in the steady-state protein level of endogenous Smad5, which can be reversed by the proteasome inhibitor, lactacystin. In contrast, little change was seen in the steady-state levels of Smad2, Smad3, and Smad7 or the membrane-bound TGF-β receptors, respectively. These results suggest that Smurf1 specifically blocks the BMP signaling by targeting Smad5 for degradation in proteasomes. This conclusion is further supported by the fact that adding back Smad5 to the Smurf1-overexpressing cells restores the BMP-induced osteoblast conversion. Furthermore, using a Smurf1-specific siRNA, we demonstrated that the endogenous Smurf1 is required for myogenic differentiation in C2C12 cells and does operate to regulate the BMP-induced osteoblast conversion.

Originally identified through yeast two-hybrid screen as a Smad1-interacting protein, Smurf1 was shown to regulate BMP signaling by targeting both Smad1 and Smad5 for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation in proteasomes (4). Surprisingly, despite reduction in the protein level of endogenous Smad5, the increase in Smurf1 was not accompanied by any significant change in the steady-state level of Smad1 in C2C12 cells. Because the Smad1 level is already very low in these cells, it is possible that the Smurf1-mediated protein degradation only operates on substrates whose level is above a certain threshold. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that interaction between Smad1 and Smurf1 was detected only when the level of Smad1 was elevated by transient transfection of a Smad1 expression plasmid. Such threshold setting activity could be an important mechanism for establishing a graded response to BMP in vivo, which is very important for the BMP signaling to influence tissue differentiation and pattern formation during animal development. Indeed, similar property has been described for DS-murf, the Drosophila homologue of Smurf (32). During the early phase of embryogenesis prior to gastrulation, abrogation of DS-murf activity sensitizes the response of the cell to the signaling function of Decapentaplegic, the Drosophila homologue of BMP, resulting in a spatial expansion of the DPP gradient, possibly due to an increase of the Drosophila R-Smad, MAD.

Alternatively, Smad1 and Smad5 could participate in different aspects of the BMP signaling, despite sharing 90% sequence identity. Although overexpression of either Smad1 or Smad5 in C2C12 cells leads to an osteoblast phenotype (27, 30, 33), Smad5 may normally play a more prominent role in mediating the BMP signaling in certain cells as suggested by the genetic analyses of Smad1 or Smad5 null mice (34).

Following the discovery of Smurf1, Ebisawa et al. (10) demonstrated a second mode of action of Smurf1 in the TGF-β signaling pathway, in which Smurf1 binds Smad7 and uses it as an adaptor to target the ligand-activated TGF-β receptors for degradation. Similar activity has also been described for Smurf2 (6). Given the fact that C2C12 cells exhibit a distinct response to TGF-β or BMP, Smurf1 could potentially operate in either one or both pathways. However, we did not observe any change in the level of cell surface TGF-β receptors or the level of Smad2 or Smad3 phosphorylation in the Smurf1-overexpressing C2C12 cells upon TGF-β treatment for up to 4 h (Fig. 5, C and D, data not shown). Nevertheless, our results demonstrated a clear preference of Smurf1 toward the BMP pathway. The mechanism of this preference has not been understood but may be accounted for by the different modes of Smurf action in these two pathways. The interactions between Smurfs and R-Smads are constitutive, thus the elevated Smurf1 could cause a chronic decrease in Smad5 (Fig. 5A), and thereby accelerate the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. The prolonged reduction in Smad5 apparently makes the Smurf1-overexpressing cells refractory to BMP treatment. In contrast, the Smurf-mediated receptor degradation is a ligand-dependent event, which occurs usually several hours after receptor activation (6, 10). Thus, Smurfs might only attenuate the TGF-β signaling temporally at the late phase of receptor activation, but the initial signaling output might be sufficient to inhibit the myogenic differentiation of C2C12 cells. Previously, Liu et al. (35) reported that TGF-β inhibits muscle differentiation through repressing the MyoD family of transcriptional factors by promoting physical association of the phosphorylated Smad3 with MyoD. The interaction between the phosphorylated Smad3 and MyoD was observed within 30 min after the addition of TGF-β. Moreover, the Smurf1·Smad7 complex-mediated TGF-β receptor degradation requires export of the Smurf1·Smad7 complex to the cytoplasm and translocation to the plasma membrane (36, 37). This process may require auxiliary factors, and if any one of these factors is absent in C2C12 cells, the Smurf1·Smad7 action on cell surface receptors would be inoperable.

Finally, the results presented here suggest a role of the Smurf-mediated degradation of Smad5 in controlling of myogenic and osteogenic differentiation. In addition, taking advantage of the recently developed RNA interference technology, we have demonstrated the physiological requirement of Smurf1 in the promotion of myogenic differentiation and in the inhibition of BMP-mediated osteoblast conversion. As demonstrated by the successful rescue of the differentiation defect by the adenovirus-mediated expression of Smad5 and the inhibition of myogenic differentiation and the enhancement of osteoblast differentiation by the siRNA against Smurf1, our finding may generate insight into new strategies of treating bone and muscle degenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. L. Choy and R. Derynck for the retroviral expression system, M. Fijii and A. Roberts for β-galactosidase and Smad5 adenoviruses, M. Reiss for phospho-Smad3 antibody, C.-H. Heldin and P. ten Dijke for phospho-Smad2 antibody, M. Schneider for the skeletal actin-luciferase reporter construct, C. X. Deng for osteocalcin cDNA, X. F. Wang for Smad5 cDNA, and Drs. L. Samelson and S. Lipkowitz for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; BMP, bone morphogenic protein; Smurf, Smad ubiquitination regulating factor; MHC, myosin heavy chain; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; E1, ubiquitin-activating enzyme; E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; E3, ubiquitin ligase; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GM, growth medium; DM, differentiation medium; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; BSA, bovine serum albumin; Ad, adenovirus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Massagué J. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moustakas A, Souchelnytskyi S, Heldin CH. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:4359–4369. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu H, Kavsak P, Abdollah S, Wrana JL, Thomsen GH. Nature. 1999;400:687–693. doi: 10.1038/23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin X, Liang M, Feng XH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36818–36822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Chang C, Gehling DJ, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Derynck R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:974–979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman AM. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;2:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35056563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebisawa T, Fukuchi M, Murakami G, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Imamura T, Miyazono K. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:12477–12480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonni S, Wang HR, Causing CG, Kavsak P, Stroschein SL, Luo K, Wrana JL. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:587–595. doi: 10.1038/35078562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaffe D, Saxel O. Nature. 1977;270:725–727. doi: 10.1038/270725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blau HM, Chiu CP, Webster C. Cell. 1983;32:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson EN, Sternberg E, Hu JS, Spizz G, Wilcox C. J. Cell Biol. 1986;103:1799–1805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massagué J, Cheifetz S, Endo T, Nadal-Ginard B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:8206–8210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katagiri T, Yamaguchi A, Komaki M, Abe E, Takahashi N, Ikeda T, Rosen V, Wozney JM, Fujisawa-Sehara A, Suda T. J. Cell Biol. 1994;127:1755–1766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoki H, Fujii M, Imamura T, Yagi K, Takehara K, Kato M, Miyazono K. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:1483–1489. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.8.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgenstern JP, Land H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choy L, Skillington J, Derynck R. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:667–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng X-H, Zhang Y, Wu R-Y, Derynck R. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2153–2163. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paradis P, MacLellan WR, Belaguli NS, Schwartz RJ, Schneider MD. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:10827–10833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faure S, Lee MA, Keller T, ten Dijke P, Whitman M. Development. 2000;127:2917–2931. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu C, Gaca MD, Swenson ES, Vellucci VF, Reiss M, Wells RG. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11721–11728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desbois C, Hogue DA, Karsenty G. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:1183–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin HY, Wang XF, Ng-Eaton E, Weinberg RA, Lodish HF. Cell. 1992;68:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii M, Takeda K, Imamura T, Aoki H, Sampath TK, Enomoto S, Kawabata M, Kato M, Ichijo H, Miyazono K. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:3801–3813. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weintraub H. Cell. 1993;75:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson EN, Klein WH. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KS, Kim HJ, Li QL, Chi XZ, Ueta C, Komori T, Wozney JM, Kim EG, Choi JY, Ryoo HM, Bae SC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:8783–8792. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8783-8792.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Hill CS. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:283–294. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podos SD, Hanson KK, Wang YC, Ferguson EL. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:567–578. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto N, Akiyama S, Katagiri T, Namiki M, Kurokawa T, Suda T. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;238:574–580. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang H, Brown CW, Matzuk MM. Endocr. Rev. 2002;23:787–823. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu D, Black BL, Derynck R. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2950–2966. doi: 10.1101/gad.925901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki C, Murakami G, Fukuchi M, Shimanuki T, Shikauchi Y, Imamura T, Miyazono K. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39919–39925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tajima Y, Goto K, Yoshida M, Shinomiya K, Sekimoto T, Yoneda Y, Miyazono K, Imamura T. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10716–10721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]