Summary

Introduction. The key element of a safe workplace for employees is the maintenance of fire safety. Thermal, chemical, and electrical burns are common types of burns at the workplace. This study assessed the epidemiology of work-related burn injuries on the basis of the workers treated in a regional burn centre. Methods. Two years’ retrospective data (2005-2006) from the Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons of the Joseph M. Still Burn Center at Doctors Hospital in Augusta, Georgia, were collected and analysed. Results. During the time period studied, 2510 adult patients with acute burns were admitted; 384 cases (15%) were work-related. The average age of the patients was 37 yr (range, 15-72 yr). Males constituted the majority (90%) of workrelated burn injury admissions. The racial distribution was in accordance with the Centre’s admission census. Industrial plant explosions accounted for the highest number of work-related burns and, relatively, a significant number of patients had chemical burns. The average length of hospital stay was 5.54 days. Only three patients did not have health insurance and four patients (1%) died. Conclusion. Burn injuries at the workplace predominantly occur among young male workers, and the study has shown that chemical burns are relatively frequent. This study functions as the basis for the evaluation of work-related burns and identification of the causes of these injuries to formulate adequate safety measures, especially for young, male employees working with chemicals.

Keywords: WORKPLACE, BURNS, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGICAL FACTORS, INDUSTRIAL PLANT EXPLOSION

Abstract

Pour la population active, l’élément clé de la sécurité au lieu de travail dépend de l’efficacité de la protection anti-incendie. Les brûlures thermiques, chimiques et électriques sont les brûlures les plus typiques au lieu de travail. Sur la base d’une analyse des travailleurs traités dans un centre régional des brûlés, les Auteurs ont évalué l’épidémiologie des brûlures qui se produisent au lieu de travail. Méthodes. Les Auteurs ont collecté et analysé deux ans de données rétrospectives (2005-2006) qu’ils ont trouvées dans le Registre des Traumatismes du Collège Américain des Chirurgiens au Centre des Brûlés Joseph M. Still à l’Hôpital Doctors (Augusta) en Géorgie. Résultats. Au cours de la période étudiée, 2510 patients adultes atteints de brûlures graves ont été admis, dont 384 (15%) en relation à un accident au lieu de travail. L’âge moyen des patients était de 37 ans (variation, 15-72 ans). La majorité (90%) des patients hospitalisés à cause de brûlures subies au lieu de travail étaient du sexe masculin. La répartition raciale était conforme aux données du recensement du Centre. Les explosions des installations industrielles ont représenté la proportion la plus élevée des brûlures liées au travail et conséquemment un nombre important de ces patients présentaient des brûlures chimiques. La durée moyenne de l’hospitalisation était de 5,54 jours. Seulement trois patients n’avaient pas d’assurance maladie et quatre patients (1%) sont décédés. Conclusion. Les brûlures subies au travail se produisent principalement chez les jeunes travailleurs du sexe masculin, et l’étude a montré que les brûlures chimiques sont relativement fréquentes. Cette étude sert comme base pour l’évaluation des brûlures liées au monde du travail et pour l’identification de leurs causes dans le but de formuler des mesures de sécurité adéquates, en particulier pour le personnel du sexe masculin qui travaille avec les produits chimiques.

Introduction

Burns in the workplace are a substantial social and economic threat to individuals and families, as also to the community. Despite numerous safety measures and guidelines, burns in the workplace continue to account for a a considerable proportion of all burns.1 The key element of a safe workplace for employees is to ensure fire safety. Statistics presented by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration show that in the US work-related fires and explosions account for more than 5,000 burn injuries each year. There are studies showing a substantially high number of burn injuries occurring in the workplace, ranging from 10 to 45% of all burns.1-6 One study observed that 40% of all burn deaths were related to workplace fires and explosions and that 20% of all cases of thermal burns in admitted patients occurred at work.3 Another study reported that 42% of all work-related injuries were burns.7 The National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries reported that in 2007 there were 617 work-related deaths in the US, of which about 10% were fire- or burn-related. Death due to electric burns was the most frequent cause (6%) of these burns.8 A hospital-based study showed that with regard to the causes of the accidents suffered by burn victims treated as hospital in-patients, the majority of the accidents were work-related.5 The study also showed that young workers and African American workers experienced the highest burns rate, which was respectively two and four times higher than that of their older and Caucasian counterparts.5 A population-based national survey among the working-age population (aged 18-64 yr) revealed that annually (1997- 1999) work-related burns (3.3%) were almost twice as frequent as non work-related burns (1.8%).7 Within the working age population, employed men and women sustained more work-related injuries than non work-related injuries.7 Some of the common types of workrelated burn injuries include chemical, thermal, electrical, contact, and scald burns.1,5 Reviewing the literature we noted that there was no comprehensive national surveillance system for occupational injuries and illnesses. Two studies mentioned that owing to the lack of a national comprehensive surveillance system for occupational injuries and illness, the major source of US occupational health data relied on the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) annual survey of occupational injuries and illnesses, workers’ compensation records, and physician reporting systems.9,10 Our study is part of a continued epidemiological observation of work-related burns from the health care providers’ perspective in a regional burn centre.

Methods and materials

To complete this study, data from January 2005 until December 2006 were obtained and reviewed from the Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons of the Joseph M. Still Burn Center at Doctors Hospital in Augusta, Georgia. The working age population was considered to be patients aged 18 to 64 yr.7 The data retrospectively collected and analysed included information about the age, sex, race, occupation, type of burn injury sustained, aetiology, percentage of total body surface area (TBSA) affected, length of hospital stay (LOS), place of occurrence, and insurance status of the various patients.

Results

During the time period studied, 3896 patients with acute burns were admitted, of whom 2510 were between 18 and 64 years of age. Among these cohorts, 384 patients (15%) sustained their burns at work.

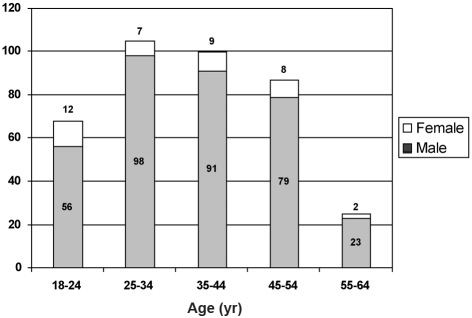

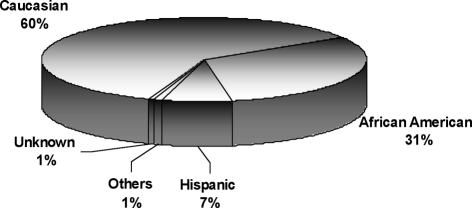

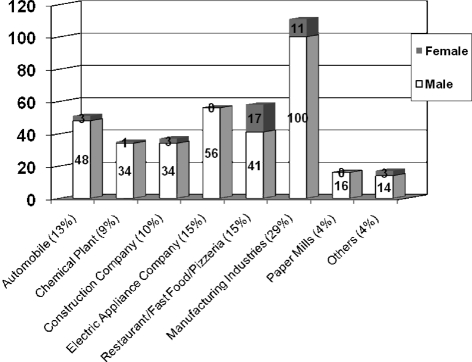

Males accounted for the majority of work-related burns (346, 90%) and their average age was 37.33 yr (SD = 11.22). Age and sex distribution are illustrated in Fig. 1. The racial distribution was found to be 60% Caucasian, 31% African American, 7% Hispanic, and 1% other (Fig. 2). The average percentage of TBSA burned was 6.5% (SD = 9.67); 16 patients (4%) had injuries that involved more than 25% TBSA, while 23% had injuries involving 1% TBSA or less. Industrial plants accounted for 111 cases (29%) of the burn injuries, followed by activities related to food preparation (restaurant / fast food / pizzeria): 58 cases (15%); working in electrical companies and stores: 56 (15%); and working in automotive servicing shops or due to motor-vehicle accidents: 51 (13%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1. Age and sex distribution of the patients.

Fig. 2. Racial distribution of the patients.

Fig. 3. Distribution of burns by workplace and sex.

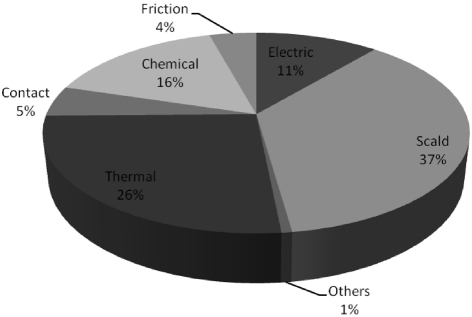

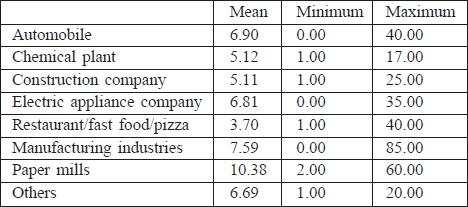

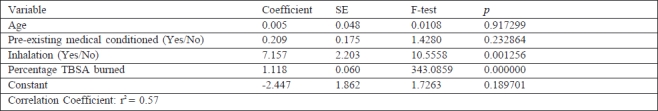

Table I shows that burns sustained in a restaurant/fast food/pizzeria were smaller in size (average, <5% TBSA) than burns that occurred in other workplaces, while patients who sustained burns while working in manufacturing or paper industries suffered extensive burns (average >60% TBSA). Categorizing by burn aetiology, hot water and grease scalds accounted for 37% of all work-related burns, thermal burns 26%, chemical burns 16%, and electric burns 11% (Fig. 4). Chemical, electric, and friction burns accounted for 60% of all smaller burns (=1% TBSA). The total length of hospital stay (LOS) for the survivors was 2104 hospital days, which ranged from 1 to 183 days, with an average of 5.54 days per patient. A multi-variable regression model showed that, for every 1% increase in TBSA, there was a 1.12-day increase in LOS, while associated inhalation injuries were 7.16 times more likely LOS adjusted for age and pre-existing medical condition of the patients (Table II). The data showed that all but three of the patients admitted were insured, 30 (7.8%) suffered respiratory injuries, and four patients (1%) died. Of the four who died, one sustained 85% TBSA thermal burns due to an explosion with inhalation, one had 56% thermal burns from a flash fire with inhalation, one had a 4% scald with inhalation, and the last one had a 4% electric burn. Only six patients were admitted with less than 1% burns - these had either inhalation injuries or electrical or chemical burns.

Table I. Average percentage total body surface area burned by workplace.

Fig. 4. Type of burns.

Table II. Multiple variable linear regression of hospital length of stay.

Discussion

Since the majority of previously published studies were specifically industry- or occupational health-based, while our study was performed using healthcare provider data, an appropriate comparison could not be drawn. Our study showed a lower proportion of work-related burn admissions (15%) than various previous studies, which reported 20-40% work-related burn admissions.5,7,11-13 The lower percentage in our study could be due to underreporting of work-related burns to the health care providers. It is not uncommon for hospital data to underreport work-related burns, especially when the injuries involve domestic help or undocumented immigrant workers.7,9,10 In previous studies, African Americans were found to have more work-related burns than their Caucasian counterparts.5,11,14 In our study the racial distribution of workplace burns was consistent with the demography of the Centre’s patients (Caucasians to African Americans = 2 to 1) and no particular race suffered an increased number of burns. Some of the findings of this review are consistent with those of past studies, such as the fact that young males were at greatest risk of burns at the workplace,1,5,15 and also that, in general, most of the patients admitted to our centre with chemical burns and scalds sustained their injuries at the workplace. 1,5 Unlike some previous studies, ours considered chemical burns separately, since we received a large number of patients with chemical burns. Sixteen per cent of workplace-related burns were due to chemicals, compared to an average of 3.92% over the last 10 years reported in the burn centre chemical burns census.

The average TBSA of 6.5% in our study was low compared to many previous studies.2,16,17 This may be because a large number of patients had chemical and electric burns, and inhalation injuries. The average LOS in our patient population was 5.54 days, which was lower than the 8.5 to 11.1 days reported in previous studies.1,5,16 The percentage TBSA burned was found to be higher in certain workplaces and with certain types of burns. Burns in manufacturing industries and in paper mills are relatively larger in size, most of them being due to explosions and flash fire. Although there is a higher incidence of burns in workplaces like restaurants / fast foods / pizzerias, burns sustained in these places are relatively smaller in size and depth.

In 1991, Personick reported that in restaurants, burns accounted for 12% of work-related injuries.18 In our study we found that 15% of all work-related burns occurred in restaurants, including fast foods and pizzerias.

This retrospective review identified workplaces and some aetiological factors associated with burns. It also identified workplaces that might cause more severe burns. Burn injuries sustained in manufacturing industries and paper mills tended to be more severe. Restaurant workers were more likely to sustain smaller burns. Most of the explosion burns were severe - contact or mechanical/friction burns were less severe.

Health care provider-based data are considered to be the most authentic source for work-related injuries.7 Hospital- or employer-based injury data potentially underestimate the incidence. For instance, burns sustained by selfemployed persons, informal workers (e.g. housekeepers, undocumented immigrant workers), farm workers, and workers in small businesses may fail to report workplace-related injuries.19 The data used in this review were obtained from our hospital records and we acknowledge the fact that as a result of inadequate information on patients’ charts regarding the place of injury, our study may not include many workplace-related burns treated in our Burn Centre.

Conclusions

Workplace burn injuries predominantly occur among young male workers, and this study has shown that chemicals and scalds are the leading causes. Contributory factors include inexperience, failure to enforce safety regulations, inadequate training of employees with regard to handling bio-hazardous materials, and employee non-compliance. This study can serve as the basis for the evaluation of work-related burns. Identification of the causes of such injuries helps to formulate adequate safety measures, especially for young male employees who work where chemicals are widely used.

References

- 1.Munnoch D.A., Darcy C.M., Whallett E.J. et al. Work-related burns in South Wales 1995-96. Burns. 2000;26:565–570. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll S.M., Gough M., Eadie P.A. et al. A 3-year epidemiological review of burn unit admissions in Dublin, Ireland: 1988-91. Burns. 1995;21:379–382. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iskrant A.P. Statistics and epidemiology of burns. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1967;43:636–645. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pegg S.P., Miller P.M., Sticklen E.J. et al. Epidemiology of industrial burns in Brisbane. Burns. 1986;12:484–490. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(86)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossignol A.M., Locke J.A., Boyle C.M. et al. Epidemiology of workrelated burn injuries in Massachusetts requiring hospitalization. J Trauma. 1986;26:1097–1101. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198612000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossignol A.M., Locke J.A., Burke J.F. Employment status and the frequency and causes of burn injuries in New England. J Occup Med. 1989;31:751–757. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198909000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith G.S., Wellman H.M., Sorock G.S. et al. Injuries at work in the US adult population: Contributions to the total injury burden. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1213–1219. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.USDL - United States Department of Labor, News, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Accessed March 30, 2010. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/cfoi_08202008.pdf

- 9.Azaroff L.S., Levenstein C., Wegman D.H. Occupational injury and illness surveillance: Conceptual filters explain underreporting. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1421–1429. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stout N., Bell C. Effectiveness of source documents for identifying fatal occupational injuries: A synthesis of studies. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:725–728. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.6.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark W.R., Lerner D. Regional burn survery: Two years of hospitalized burned patients in central New York. J Trauma. 1978;18:522–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacArthur J.D., Moore F.D. Epidemiology of burns - the burnprone patient. JAMA. 1975;231:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandelcorn E., Gomez M., Cartotto R.C. Work-related burn injuries in Ontario, Canada: Has anything changed in the last 10 years? Burns. 2003;29:469–472. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feck G., Baptiste M.M., Greenwald P. The incidence of hospitalized burn injury in Upstate New York. Am J Public Health. 1977;67:966–967. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.10.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson E. The epidemiology of burns in secondary care, in a population of 2.6 million. Burns. 1998;24:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(98)80001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng D., Anastakis D., Douglas L.G. et al. Work-related burns: A 6- year retrospective study. Burns. 1991;17:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(91)90140-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tejerina C., Reig A., Cocina J. et al. An epidemiological study of burn patients in Valencia, Spain, during 1989. Burns. 1992;18:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(92)90112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Personick M.E. Profiles in safety and health: Eating and drinking places. Monthly Labor Rev. 1991;114:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Occupational injuries and illnesses: Counts, rates, and characteristics, 1998. Washington DC, US Dept of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics Data, July 2001, Bulletin 2538,. 2001