Abstract

A highly efficient ligand-accelerated Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H/arylboron cross-coupling reaction of phenylacetic acid substrates is reported. Using Ac-Ile-OH as the ligand and Ag2CO3 as the oxidant, a fast, high yielding, operationally simple, and functional group–tolerant protocol has been developed for the cross-coupling of phenylacetic acid substrates with aryltrifluoroborates. This ligand scaffold has also been shown to improve substantially catalysis using 1 atm O2 as the sole reoxidant, which sheds light on the path forward in developing optimized ligands for aerobic C–H/arylboron cross-coupling.

1. Introduction

Since the 1970s, the discovery and development of Pd(0)-catalyzed reactions of aryl and alkyl halides have revolutionized how organic chemists envision forming new carbon–carbon (C–C) and carbon–heteroatom (C–Y) bonds.1,2 The versatility and practicality of these transformations stem from specially tailored phosphine and N-heterocyclic carbene ligands, which can accelerate both oxidative addition and reductive elimination, thereby enhancing the overall catalytic efficiency and broadening substrate scope.2 In contrast, fewer ligands are compatible with analogous Pd(II)-catalyzed carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bond functionalization reactions,3–10 which has hampered progress in this area. Recently, our group made strides on this front with the discovery that mono-N-protected amino acid ligands4 could accelerate Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H olefination reactions along a Pd(II)/Pd(0) catalytic cycle (Eq. 1).5 Based on preliminary mechanistic data,5c we believe that the observed acceleration derives from an increase in the rate of C–H cleavage. This calls into question whether mono-N-protected amino acids would be compatible with Pd(II)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of C–H bonds with organometallic reagents (Eq. 2),7,11,12 which have completely different elementary steps following C–H cleavage (transmetalation and reductive elimination). Identification of appropriate ligand scaffolds capable of accelerating C–H/R–M cross-coupling reactions is fundamentally important for improving the scope and practicality of this new class of reactions, which are still in their infancy.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

In early 2006, our group reported the first Pd(II)-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of C(sp2)–H bonds and organometallic reagents.12 Since that initial report, our group13,14 and others15,16 have gone on to expand this mode of reactivity to an increasingly versatile collection of substrates and coupling partners.17–21 Generally speaking, however, the catalytic efficiency across these examples remains unsatisfactory,16 pointing to a need for ligands to enhance reactivity and turnover. Because catalytic C–H/R–M cross-coupling possesses several fundamentally distinct elementary steps (C–H cleavage, transmetalation, reductive elimination, and reoxidation), it remains a significant challenge to identify a ligand that is compatible with all of these steps. Nevertheless, encouraged by our work in ligand-accelerated C–H olefination, we sought to establish a ligand-accelerated Pd(II)-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of organoboron reagents with phenylacetic acids, a major class of synthetically versatile substrates. This particular reaction intrigued us because original methodology from our lab13 suffered from several limitations, including long reaction times (48 h), incompatibility with oxidants that are operationally convenient to use such as Ag(I) salts, the need for high pressure O2 (20 atm), and limited substrate scope.22

Herein, we disclose the results of our studies, which represent to the best of our knowledge the first example of ligand-accelerated Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H/arylboron cross-coupling. By using amino acid ligands in conjunction with Ag2CO3 as a stoichiometric reoxidant, we have developed a new protocol for the functionalization of phenylacetic acid substrates that offers shorter reaction times, improved substrate scope, and higher yields compared to our previous method.13 By using ligand acceleration under aerobic conditions, we also demonstrate that good yields can be obtained under relatively low pressures of O2. Importantly, this work establishes that mono-N-protected amino acids are promising ligand scaffolds for further optimization owing to their compatibility with the transmetalation, reductive elimination, and reoxidation steps in C–H/R–M cross-coupling.

2. Results and Discussion

We began by revisiting our previously reported conditions.13 One of the drawbacks that hampered the practical utility of that protocol was the need for high pressure O2 (20 atm), which signaled to us that reoxidation of Pd(0) to catalytically active Pd(II) was problematic (see below for a depiction of the speculative catalytic cycle). Thus for the purposes of achieving efficient turnover under mild conditions, we first turned our attention to other reoxidants, with the long term goal of developing conditions in which 1 atm air could be used as the sole reoxidant. After extensive screening, it was found that Ag2CO3 functioned smoothly for these purposes, giving high conversions in this ligand accelerated C–H/arylboron cross-coupling reaction.23 It should be noted that although using Ag2CO3 is unsuitable for large-scale industrial production, we opted to use it here in the interest of developing a highly efficient protocol for use in academic and medicinal chemistry laboratories.

For our optimization studies, we selected 2-trifluorophenylacetic acid (1a) as our screening substrate because it was known to be relatively unreactive in the absence of ligands (Entry 1, Table 1).22 Using Ag2CO3 as the oxidant, we examined the effect of amino acid ligands. We first probed a range of commercially available mono-N-Boc-protected amino acids (Entries 2–8), and among those examined, we found those with hydrophobic residues on the backbone (e.g., Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, and Phe) to be highly effective. We then optimized the N-protecting group (Entries 8–14), which led to identification of Ac-Ile-OH as an optimal ligand. Substitution of the nitrogen atom with an electron-withdrawing was necessary for reactivity, as use of both Me-Ile-OH and H-Ile-OH shut down the reaction (Entries 10 an 11). This observation suggests that an electron-deficient Pd(II) center is necessary for substrate coordination and subsequent C–H cleavage. We observed that with 5 mol% Pd(OAc)2, Ac-Ile-OH loadings of 2.5 mol%, 5 mol%, 10 mol% and 15 mol% gave nearly identical initial rates (as approximated by measuring the conversion at 20 min) and overall conversion after 2 h. Given that Ac-Ile-OH is relatively inexpensive, 10 mol% ligand was used throughout this work for convenience in weighing.

Table 1.

Ligand optimization.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligandb | % Conv. | Entry | Ligandb | % Conv. |

| 1 | --- | 13 | 9 | H-Ile-OH | 0 |

| 2 | Boc-Gly-OH | 61 | 10 | Me-Ile-OH | 0 |

| 3 | Boc-Ala-OH | 77 | 11 | Formyl-Ile-OH | 62 |

| 4 | Boc-Phe-OH | 83 | 12 | Ac-Ile-OH | 89 |

| 5 | Boc-Val-OH | 82 | 13 | Fmoc-Ile-OH | 79 |

| 6 | Boc-Leu-OH | 81 | 14 | Cbz-Ile-OH | 76 |

| 7 | Boc-t-Leu-OH | 79 | 15 | Ac-Val-OH | 79 |

| 8 | Boc-Ile-OH | 81 | 16 | Ac-Leu-OH | 87 |

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. Isolated yield is given in parentheses.

Boc = tert-butyloxycarbonyl, Cbz = carbobenzyloxy, Fmoc = fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl, Ac = acetyl.

In our previous studies using O2 as the oxidant,13,14b the presence of 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ) was found to be crucial for both the C–C reductive elimination12a,24,25 and reoxidation steps. In contrast, in this protocol using Ag2CO3, BQ was not required. 5 mol% BQ was used merely to improve reproducibility. Here, the diminished importance of BQ is likely related to the ability of Ag2CO3 to promote both C–C reductive elimination through one-electron oxidation26 and reoxidation of Pd(0) by an inner-sphere mechanism, whereby electron transfer proceeds through a putative Pd–Ag interaction.25

Acceptable conversions were obtained with representative substrates during our initial screen with 1 equiv. Ag2CO3 and 1.5 equiv. PhBF3K (Table 2).27 However, we found the phenylacetic acid starting materials to be difficult to isolate from the arylated products on mmol scale. Thus, in order to simplify purification and improve operational simplicity, we sought to refine the conditions to drive the reaction to completion. We further examined alternative arylboron coupling partners (Table 3), and found that both aryltrifluoroborates and the pinacol esters of arylboronic acids (ArBPin) provided nearly equivalent product yields. We hypothesized that under our conditions undesired homocoupling was consuming both oxidant and the arylboron reagent. We thus increased the amount of Ag2CO3 to 2 equiv. and arylboron reagent to 3 equiv. and observed that quantitative conversion of 3a could be achieved (Entries 1 and 2).28 Under these conditions, we found that reaction worked equally well under N2, O2, or air.

Table 2.

Initial results with representative phenylacetic acids.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Ligand | % Conv. | Product | Ligand | % Conv. |

|

--- | 8 |  |

--- | 12 |

| Ac-Ile-OH | 89 | Ac-Ile-OH | 77 | ||

|

--- | 16 |  |

--- | 33 |

| Ac-Ile-OH | 69 | Ac-Ile-OH | 62 | ||

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture

Table 3.

Examination of arylboron coupling partners.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ph–BX2 | % Conv. | Entry | Ph–BX2 | % Conv. |

| 1 | Ph–BF3K | 89 [>99]b | 4 | Ph–B(OH)2 | 6 |

| 2 |  |

85 [>99]b | 5 |

|

9 |

| 3 | 58 | 6 |  |

1 | |

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture

PhBX2 (3.0 equiv.), Ag2CO3 (2.0 equiv.).

We also found that the reaction could also be performed at lower temperature, albeit with extended reaction time (Table 4). For example at 70 °C, the reaction to form 3a was found to proceed to >99% conversion using Ac-Ile-OH as the ligand and 16% in the absence of ligand after 36 h.

Table 4.

Conversion of 1a to 3a at 70 °C.a

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | % Conv. |

| 1 | --- | 16 |

| 2 | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 |

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture.

We next examined the effect of the ligand on the reaction profile with substrate 1a. Two independent reactions were set up in the presence and absence of Ac-Ile-OH and allowed to run for 2 h. During this time period, small aliquots were removed at regular intervals and analyzed by 1H NMR to determine the conversion. This process was repeated three times and the data were averaged. The results, plotted in Figure 1, show a roughly 8-fold increase in the initial rate using Ac-Ile-OH.29 We observed a slight deviation from strict linearity in the early part of the reaction profile, presumably due to slow release of the aryltrifluoroborate to the active boronic acid or boronate species via hydrolysis during the course of the reaction.27d This effect became more pronounced at lower temperature. Nevertheless, a clear rate increase in the presence of Ac-Ile-OH is evident from the data.

Figure 1.

Reaction profile for the reaction of 1a with 2a in the presence and absence of Ac-Ile-OH. Each data point represents the average of three independent trials. The initial rates are calculated for the data points in the 5–20 min time interval using linear regression. Beyond 2 h, no additional product conversion was observed in the trials without ligand. See Supporting Information for detailed experimental procedures.

Next, we probed phenylacetic acid substrate scope (Table 5). To our delight, we found that our new protocol was highly tolerant of a variety of different substituents including alkyl groups (3b and 3d), alkoxy groups (3j, 3k), and halides (3f–3h). Notably strongly electron-withdrawing groups, such trifluoromethyl (3a, 3c, and 3e), nitro (3i), and ketone (3n) groups also gave high yields, which qualitatively suggests that simple electrophilic palladation is not the operative mechanism for C–H cleavage. Our protocol was found to tolerate monosubstitution at the α-position ((rac)-3m), providing a means for the diversification of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Naproxen ((S)-1n) and Ketoprofen ((rac)-1o), which gave products (S)-3n and (rac)-3o, respectively. Importantly, we found that chiral center in (S)-3n did not epimerize under the reaction condition when an enantiopure starting material was used. With chiral, α-substituted starting material (rac)-3m, racemic and enantiopure ligands were found to give comparable yields (see Supporting Information). α,α,-Disubstituted substrates were found to give substantially lower yields under these conditions.30 In the absence of a sterically bulky group at the ortho-, meta-, or α-positions, the reaction gave primarily the diarylated product, but acceptable yields of the monoarylated product could be obtained by using 1 equiv. of the coupling partner (e.g., 3e). For each substrate, we ran a control experiment in the absence of Ac-Ile-OH. Generally, the presence of Ac-Ile-OH drastically improved the yield. In the absence of ligand, only two electron-rich substrates 3e and 3k gave over 60% yield. Substrates bearing electron-withdrawing substituents (e.g., 3a, 3c, 3e, 3f–3i) were highly unreactive in the absence of Ac-Ile-OH.

Table 5.

Phenylacetic acid substrate scope.a

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Ligand | % Conv. | Product | Ligand | % Conv. | Product | Ligand | % Conv. |

|

--- | 17 |  |

--- | 5 |  |

--- | 72 |

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (98) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (98) | Ac-Ile-OH | 96 (85) | |||

|

--- | 44 |  |

--- | 20 |  |

--- | 22 |

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (97) | Ac-Ile-OH | 97 (96) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (80) | |||

|

--- | 6 |  |

--- | 10 |  |

--- | 24d |

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (97) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (98) | Ac-Ile-OH | 78 (73)d | |||

|

--- | 63 |  |

--- | 2 |  |

--- | 41e |

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (95) | Ac-Ile-OH | 87 (69) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (97)e,f | |||

|

--- | 6 |  |

--- | 38 |  |

--- | 16d |

| Ac-Ile-OH | 57 (52)b,c | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (94) | Ac-Ile-OH | 89 (83)d | |||

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture. Isolated yield is given in parentheses.

1.0 equiv. PhBF3K was used.

28% of the di-arylated product (3e’) was also isolated.

Racemic starting material was used.

Enantiopure starting material was used.

The product was isolated in >99:1 er, as determined by chiral HPLC (see Supporting Information).

Subsequently, we investigated the compatibility of our protocol with various substituted arylboron coupling partners (Table 6). We were pleased to find that several different substituted aryltrifluoroborates were well tolerated, giving excellent conversions (3p–3v). Importantly, we were also able to couple a heterocyclic compound under our new conditions (3w). Arylboron reagents bearing substituents at the ortho-position were found to be unreactive, presumably due to steric encumbrance.

Table 6.

| Product | Ligand | % Conv. | Product | Ligand | % Conv. | Product | Ligand | % Conv. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

--- | 19 |  |

--- | 46 |  |

--- | 18 |

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (99) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (87) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (87) | |||

|

--- | 23 |  |

--- | 28 |  |

--- | 6c |

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (92) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (94) | Ac-Ile-OH | 44 (37)c | |||

|

--- | 12 |  |

--- | 19 | |||

| Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (95) | Ac-Ile-OH | >99 (98) |

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture. Isolated yield is given in parentheses.

The reaction conditions were identical to those used in Table 2.

The corresponding ArBPin (3 equiv.) coupling partner was used.

We then shifted our focus to establishing a ligand-accelerated protocol in which O2 was used as the terminal reoxidant (Table 7).31 We again examined amino acid ligands, first turning our attention to commercially available mono-N-Boc-protected amino acids (Entries 2–10). Of those tested, Boc-Val-OH (Entry 10) was found to be optimal. We then sought to tune the N-protecting group, by modulating the steric and electronic properties of the chelating nitrogen atom (Entries 11–19). However, other amide- (Entries 13–15) and carbamate-type (Entries 16–19) protecting groups, were found to offer no further improvements. The optimal ligand from above, Ac-Ile-OH, gave reproducibly lower conversion than Boc-Val-OH (Entry 20) For the remainder of the aerobic studies described herein, Boc-Val-OH was used as the ligand.

Table 7.

Ligand optimization under 1 atm O2.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligandb | % Conv. | Entry | Ligandb | % Conv. |

| 1 | --- | 9 | 11 | H-Val-OH | 6 |

| 2 | Boc-Ala-OH | 39 | 12 | Formyl-Val-OH | 52 |

| 3 | Boc-Phe-OH | 48 | 13 | Ac-Val-OH | 52 |

| 4 | Boc-Ser-OH | 26 | 14 | Piv-Val-OH | 9 |

| 5 | Boc-Thr(t-Bu)-OH | 40 | 15 | Ada-Val-OH | 24 |

| 6 | Boc-Aib-OH | 44 | 16 | Me(O2C)-Val-OH | 50 |

| 7 | Boc-Leu-OH | 57 | 17 | Et(O2C)-Val-OH | 46 |

| 8 | Boc-t--Leu-OH | 57 | 18 | Cbz-Val-OH | 52 |

| 9 | Boc-Ile-OH | 49 | 19 | i-Bu(O2C)-Val-OH | 49 |

| 10 | Boc-Val-OH | 65 | 20 | Ac-Ile-OH | 56 |

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Aib = α-aminoisobutyric acid, Ada = 1-adamantyl(CO), Piv = pivaloyl.

To probe the efficacy of this reaction under different pressures, reactions were conducted at 1 atm, 5 atm, 20 atm O2, and 20 atm air, and three representative substrates were examined (Table 8).32 We found that raising the O2 pressure from 1 atm to 5 atm improved the conversions. However, further increasing the O2 pressure from 5 atm to 20 atm had a comparatively modest effect. BQ was required for catalytic turnover. Using 5 mol% BQ gave the fastest initial rates; however, 20 mol% BQ was optimal for overall yield (see Supporting Information). Given that our old protocol required 20 atm O2/48 h to achieve moderate turnover,13,22 these data serve as compelling evidence that further ligand-optimization could lead to practical C–H/R–M cross-coupling reactions under ambient air. Moreover, the fact that both 5 atm and 20 atm O2 gave similar conversions after 8 h shows that above 5 atm O2, pressure may no longer be a critical variable for enabling turnover in the presence of Boc-Val-OH. For each data point in Table 8, a control experiment was performed in the absence of ligand, and substantially lower conversions were observed in each case.

Table 8.

Results under different conditions using O2 as the terminal oxidant.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Ligand |

1 atm O2 (24 h) |

5 atm O2 (8 h) |

20 atm O2 (8 h) |

20 atm air (8 h) |

|

--- | 12 | 32 | 26 | 30 |

| Boc-Val-OH | 65 | 96 (91) | 97 (93) | 77 | |

|

--- | 21 | 31 | 49 | 35 |

| Boc-Val-OH | 53 | 75 | 72 (68) | 73 | |

|

--- | 4 | 8 | 13 | 8 |

| Boc-Val-OH | 17 | 62 | 83 (74) | 49 | |

| One-pot intermolecular competition experiment data.a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Entry | Ligand | Time (min) | % Conv. 3a | % Conv. 3b | k3a / k3b |

| 1 | --- | 60 | 9 | 18 | 0.48 |

| 2 | Ac-Ile-OH | 20 | 36 | 16 | 2.17 |

The conversion was determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture. Isolated yield is given in parentheses. After the times shown, no additional product formation was observed.

The conversions were determined by 1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture. See Supporting Information for experimental details.

A thorough understanding of the mechanism of this reaction will require detailed computational, kinetic, and structural analysis, efforts that are currently underway in our laboratory and in collaboration with other groups. In the meantime, we would like to highlight several observations that we have made thus far to help frame future mechanistic studies. The reaction begins with formation of the catalytically active Pd(II) species, which we speculate to be a monomeric Pd(II)-catalyst with a single bound amino acid, consistent with our earlier work in this area.4,33 Attempts to isolate and characterize the active Ac-Ile-OH-bound Pd(II) catalyst and test its reactivity, however, have not been fruitful thus far.34,35

Two different pathways would then theoretically lead to a common [Pd(II)Ar1Ar2] intermediate (Scheme 1). In Path A, transmetalation to generate a [Pd(II)Ar1] species would precede C–H cleavage. In Path B, on the other hand, C–H cleavage would take place first, followed by transmetallation. Though we cannot definitively rule out Path B, we current favor Path A based on the fact that the reactivity trends in Table 5 (both with and without Ac-Ile-OH) closely parallel those seen in Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H olefination of phenylacetic acids,5c where C–H cleavage is thought to be the first step of the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 1.

Possible reaction pathways.

To understand the mechanism of carboxylate-directed C–H cleavage in this reaction,5c,7a,36–38 we first took note of the tolerance for both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents on the aromatic ring in the presence of Ac-Ile-OH (Table 5). To further probe the relative reactivities of electron-rich and electron-poor phenylacetic acids, we performed competition experiments between substrates 1a and 1b under abridged reaction times to measure the relative initial rates (Table 8).39 We found that in the absence of ligand, electron-rich substrate 1b gave a higher initial rate. In the presence of Ac-Ile-OH, we found that electron poor substrate 1a gave a higher initial rate. The results were consistent with the single-component initial rate data (Table 9). Overall, the trends from these competition experiment are very similar to what we observed in ligand-accelerated C–H olefination.5c Based on these findings, we propose that the C–H cleavage event proceeds via a concerted metallation/deprotonation pathway in the presence of Ac-Ile-OH, and an electrophilic palladation mechanism in the absence of Ac-Ile-OH (Figure 2).5c,40,41

Table 9.

Comparison of the Initial Rates for Single-Component Reactions of 1a and 1b in the presence and absence of Ac-Ile-OH.a,b

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a (R = CF3) | 3b (R = Me) | |||

| Entry | Ligand | k3a ([M]/min) | k3b ([M]/min) | k3a / k3b |

| 1 | --- | 4.5 × 10−4 | 7.1 × 10−4 | 0.66 |

| 2 | Ac-Ile-OH | 3.7 × 10−3 | 1.5 × 10−3 | 2.47 |

See Supporting Information for experimental details.

As was discussed with Figure 1, slight deviations from linearity were observed in the early parts of the rate profiles. Linear regression was used here with the understanding that it introduces some degree of error.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanisms for Pd(II)-mediated C–H cleavage. In the absence of ligand, we propose an electrophilic palladation mechanism (A). In the presence of ligand, we propose a concerted metallation/deprotonation mechanism with external (B) or internal (C and D) base.

Subsequent to C–H cleavage, transmetallation takes place with the organoboron reagent to generate a diaryl Pd(II) species. Because competitive Pd(II)-mediated homocoupling of the organometallic reagents is known to be fast,12 we speculate that the use of ArBF3K reagents27 as the coupling partners helps to suppress this undesired pathway.42 Importantly, it has previously been found that Ag(I) salts facilitate transmetallation in cross-coupling reactions.12b,14a,18d,43 Reductive elimination from the [Pd(II)Ar1Ar2] species, which could be induced by BQ or Ag(I),12a,24–26 then forges the new key C–C bond to give the arylated phenylacetic acid product.

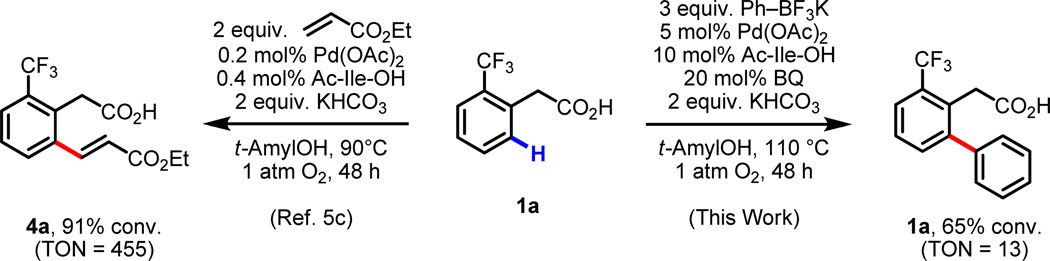

Reoxidation of Pd(0) by Ag(I) or O2 then takes place to regenerate catalytically active Pd(II) and closes the catalytic cycle. The mechanism of reoxidation with O2 warrants some additional discussion. Previously, in our ligand-accelerated C–H olefination work,5c efficient catalysis (TON > 450, TON = turnover number) was achieved under only 1 atm O2 (Scheme 2). In the present case of ligand-accelerated C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling, the maximum TONs using 1 atm O2 are roughly 30–40-fold lower. For instance, 65% conversion of product 3a with 5 mol% Pd(OAc)2 was observed after 24 h at 1 atm O2, representing a TON of 13 (Scheme 2 and Table 8). It is also noteworthy, that BQ is not required for catalysis in the case of aerobic C–H olefination but is required in aerobic C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling; in the absence of BQ, only 5% conversion of 3a was observed after 24 h under 1 atm O2 (see Supporting Information).44 Given the similarity of the reaction conditions in these two transformations, it is possible that this discrepancy in catalytic efficiency stems from a difference in the mechanism of reoxidation. In C–H olefination, the substrate disengages from the catalyst following a β-hydrogen elimination event, generating a [Pd(II)(H)(X)] species (Scheme 3). This intermediate can then react with O2 along two possible pathways, direct hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA), or a reductive elimination/oxygenation/protonation sequence (HXRE).31,45 In contrast, in the case of C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling, C–C reductive elimination, possibly promoted by BQ,12a,24,25 generates the product along with concomitant formation of a [Pd(0)] species (Scheme 4). [Pd(0)] is then be reoxidized to [Pd(II)] either by BQ or by O2.46

Scheme 2.

Comparison between ligand-accelerated Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H olefination and C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling under 1 atm O2.5c

Scheme 3.

Possible reoxidation pathways in ligand-accelerated C–H olefination.5c

Scheme 4.

Reoxidation pathway in ligand-accelerated C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling.

Detailed mechanistic and computational studies have found that either HAA or HXRE pathways can be favored depending on the ligand environment of the [Pd(II)(H)(X)] complex and the reaction conditions.45 In the presence of mono-N-protected amino acid ligands, however, the reactivity patterns of [Pd(H)(X)] intermediates have not yet been established. In our two catalytic systems (Schemes 2–4), catalyst deactivation is expected to take place primarily via aggregation of [Pd(0)] intermediates to [Pd]n (Pd black). Thus, one possible explanation for the markedly higher catalytic efficiency in C–H olefination would be to invoke a HAA mechanism for reoxidation in that reaction (Scheme 3), whereby [Pd(0)] species are avoided all together. However, other explanations could also potentially account for the observed differences in catalytic efficiency between the two reactions. For example, the coordination of a C=C moiety of the olefin coupling partner and/or olefinated product, could serve to stabilize reduced [Pd(0)] following HXRE in the C–H olefination reaction, decreasing the likelihood of precipitation to Pd black.33 Another explanation could be that the higher temperature in C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling (110 °C compared to 90 °C for C–H olefination), which we have found to be necessary for good conversion, possibly because of the higher energetic barrier for C–C reductive elimination compared with β-hydrogen elimination, could be detrimental for catalyst lifetime. Further mechanistic and computational studies are necessary to elucidate the viability of these different scenarios for reoxidation with O2.

The proposed Pd(II)/Pd(0) catalytic cycle is depicted in Scheme 4. The process begins with substrate coordination and subsequent C–H cleavage, which is presumably facilitated by the bound amino acid ligand. Transmetallation takes place, followed by reductive elimination to forge the key C–C bond with concomitant generation of Pd(0). Reoxidation with Ag(I) or O2/BQ regenerates the active catalyst.

Scheme 4.

Proposed catalytic cycle.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we report a highly efficient ligand-accelerated Pd(II)-catalyzed C(sp2)–H/arylboron cross-coupling reaction. Using mono-N-protected amino acid ligands, we were able to develop conditions to broaden phenylacetic acid substrate scope, shorten reaction times, improve product yields, and reduce catalyst loadings. We anticipate that our new operationally simple protocol using Ag2CO3 will find widespread applications in academic and medicinal chemistry laboratories. Of equal importance, we have achieved progress toward the development of a complimentary practical aerobic protocol for this Pd(II)-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction using 1 atm O2 as the sole reoxidant. Upon further development, the aerobic reaction will provide an expedient and high yielding method for large-scale production of biaryl molecules, which are especially prevalent in pharmaceuticals.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. General Information

Unless otherwise noted, all materials were used as received from commercial sources without further purification. Phenylacetic acid substrates were purchased from Acros, Sigma-Aldrich, TCI, Alfa-Aesar, and MP Biomedical and were used as received. 2-(Trifluoromethyl)phenylacetic acid (1a) was purchased from TCI; samples of 1a from other commercial sources were found to give inconsistent results. Organoboron coupling partners were procured from Frontier Scientific, Sigma Aldrich, and Combi-Blocks and used as received. 1,4-Benzoquninone (BQ) was sublimed prior to use. t-AmylOH was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Newly opened and/or freshly distilled sample of t-Amyl-OH gave the most consistent results. Commercially available amino acid ligands were purchased from Bachem, EMD, or Novabiochem. To examine whether racemic Ac-Ile-OH would give better yields with chiral (racemic) substrates, Ac-D-Ile-OH was prepared.47 All other ligands were prepared following literature precedent.5c Palladium acetate and potassium hydrogen carbonate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Fisher, respectively, and were used without further purification. All reactions were run on hot plates with oil baths calibrated to an external thermometer. Prior to beginning an experiment, the hot plate was turned on, and the oil bath was allowed to equilibrate to the desired temperature for 30 minutes. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer FT-IR Spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Inova (400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively) and Bruker DRX equipped with a 5mm DCH cryoprobe (600 MHz and 150 MHz, respectively) instruments internally referenced to tetramethylsilane or chloroform signals. The following abbreviations (or combinations thereof) were used to explain multiplicities: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, and a = apparent. The enantiomeric ratio of Me-(S)-3n was determined by integration of the HPLC trace, acquired using an Agilent Technologies 1200 series HPLC system with an integrate diode array detector (vide infra). High resolution mass spectra were recorded at the Center for Mass Spectrometry, The Scripps Research Institute.

4.2 Rate profile measurements with 2-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetic acid (1a) and o-tolylacetic acid (1b)

For each substrate, two different reaction conditions were examined: (1) without Ac-Ile-OH and (2) with Ac-Ile-OH. A 100 mL Schlenk tube containing a magnetic stir bar was charged with 1a (or 1b) (1.00 mmol), phenyltrifluoroborate (2a) (552.0 mg, 3.0 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (11.2 mg, 0.050 mmol), BQ (5.4 mg, 0.050 mmol), Ac-Ile-OH (8.7 mg, 0.05 mmol) (when used), KHCO3 (200.2 mg, 2.0 mmol), Ag2CO3 (551.5 mg, 2.0 mmol), and t-AmylOH (5.0 mL). The reaction tube was capped with a rubber stopper, then stirred at 110 °C. At the indicated time points, a small aliquot (< 0.1 mL) was removed from the vial. The aliquots were added to independent 10 mL scintillation vials containing a biphasic mixture of 2.0 N HCl solution (1.0 mL) and diethyl ether (2.0 mL). An aliquot of the organic phase was taken, concentrated in vacuo, and analyzed by 1H NMR. The conversion was determined by integration of the benzylic methylene proton signals, which appear as singlets (approximately 3.87 ppm for 1a, 3.79 ppm for 3a, 3.67 ppm for 1b, and 3.63 ppm for 3b). The procedure was repeated thee times. The resulting data were plotted, and linear regression of the time points in the 5–20 min period established the initial rate. The results are shown in Tables S4–S7 and Figures S1–S4.

4.3 General procedure for Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H/organoboron cross-coupling with phenylacetic acids (1) and potassium trifluoroborates (2)

A 25 mL sealed tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with the phenylacetic acid substrate (1) (0.50 mmol), the aryltrifluoroborate (2) (1.5 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (5.6 mg, 0.025 mmol), BQ (2.7 mg, 0.025 mmol), Ac-Ile-OH (8.7 mg, 0.05 mmol), KHCO3 (100.1 mg, 1.0 mmol), Ag2CO3 (275.8 mg, 1.0 mmol), and t-AmylOH (2.5 mL). The reaction tube was capped and immediately transferred to an oil bath at 110 °C. After being allowed to stir vigorously for 2 h, the reaction vessel was removed from the oil bath and cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. A 2.0 N HCl solution (5 mL) and diethyl ether (10 mL) were added. A small aliquot of the organic phase was taken, concentrated in vacuo, and analyzed by 1H NMR. The conversion was determined by integration of the benzylic proton signals—3 generally appears upfield from 1. To isolate the pure product 3, the biphasic mixture was basified with concentrated aqueous NaOH until the pH > 12 (as monitored by pH paper), and the resulting solution was extracted with DCM (2 × 10 mL) to remove BQ and the biaryl homocoupling byproduct, and the organic layers were back-extracted once with 2.0 N NaOH (10 mL). The combined aqueous layers were acidified via dropwise addition of concentrated HCl until the pH < 2, and the solution was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using 2:1 hexanes:EtOAc (with 3% HOAc) as the eluent. Products 3i, (rac)-3o, 3s, and 3w were prepared on a 0.2 mmol scale, using the same relative amounts of reagents. For each substrate, a control experiment in the absence of Ac-Ile-OH was run, and the conversion was determined in a similar manner; however the product (which was generally observed in scant quantities) was not isolated. The results in the presence and absence of ligand are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

4.4 General procedure for Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H/organoboron cross-coupling of phenylacetic acids (1) with potassium trifluoroborates (2)

For experiments using >1 atm of pressure, a 45 mL high pressure vessel was used. For experiments using 1 atm of pressure, a 50 mL Schlenk-type sealed tube (with a Teflon high pressure valve and side arm) was used. The reaction flask was equipped with a magnetic stir bar and was charged with the phenylacetic acid substrate (1) (0.50 mmol), the aryltrifluoroborate (2) (0.75 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (5.6 mg, 0.025 mmol), BQ (10.8 mg, 0.1 mmol), Boc-Val-OH (10.9 mg, 0.05 mmol), KHCO3 (100.1 mg, 1.0 mmol), and t-AmylOH (2.5 mL). The reaction vessel was capped and adjusted to the appropriate pressure of O2 (or air). A note of caution: when working with high pressure O2, proper safety measures (including the use of a blast shield) should be taken. After being allowed to stir vigorously for the appropriate time, the reaction vessel was removed from the oil bath and cooled to RT. The pressure was released, and a 2.0 N HCl solution (5 mL) and diethyl ether (10 mL) were added. A small aliquot of the organic phase was taken, concentrated in vacuo, and analyzed by 1H NMR. The conversion was determined by integration of the benzylic methylene proton signals, which appear as singlets—3 generally appears upfield from 1. To isolate the pure product (3), the biphasic mixture was basified with concentrated aqueous NaOH until the pH > 12 (as monitored by pH paper), the resulting solution was extracted with DCM (2 × 10 mL) to remove BQ and biphenyl (the undesired homocoupling byproduct), and the organic layers were back-extracted once with 2.0 M NaOH (10 mL). The combined aqueous layers were acidified via dropwise addition of concentrated HCl until the pH < 2, and the solution was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography using 2:1 hexanes:EtOAc (with 3% HOAc) as the eluent. For each substrate under each of the conditions reported, a control experiment in the absence of Ac-Ile-OH was run, and the conversion was determined in a similar manner; however the product (which was generally observed in scant quantities) was not isolated. The results are shown in Table 8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge TSRI, the NIH (NIGMS, 1 R01 GM084019-02), Amgen, and Eli Lilly for financial support. This work was funded by the A. P. Sloan Foundation (fellowship to J.-Q.Y.); TSRI, the NSF GRFP, the NDSEG Fellowship program, and the Skaggs Oxford Scholarship program (predoctoral fellowships to K.M.E.); and the ACS SEED program (high school internship funding for M.D.). We thank David W. Shia (Torrey Pines High School) for assistance in collecting the rate profile data. We are grateful to Frontier Scientific for the generous donation of organoboron reagents. TSRI Manuscript no. 21064.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Detailed experimental procedures, characterization of new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Reviews of Pd(0)-catalyzed C–C bond–forming reactions in total synthesis: Chemler SR, Trauner D, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4544–4568. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4544::aid-anie4544>3.0.co;2-n. Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4442–4489. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500368.

- 2.For perspectives on the importance of ligand design in Pd(0) chemistry, see: Littke AF, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:4176–4211. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4176::AID-ANIE4176>3.0.CO;2-U. Hartwig JF. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1534–1544. doi: 10.1021/ar800098p. Martin R, Buchwald SL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1461–1473. doi: 10.1021/ar800036s.

- 3.Selected reviews of Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization: Campeau L-C, Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Aldrichim. Acta. 2007;40:35–41. Satoh T, Miura M. Chem. Lett. 2007;36:200–205. Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1173–1193. doi: 10.1039/b606984n. Giri R, Shi B-F, Engle KM, Maugel N, Yu J-Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3242–3272. doi: 10.1039/b816707a. Ackermann L, Vicente R, Kapdi AR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9792–9826. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902996. Daugulis O, Do H-Q, Shabashov D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1074–1086. doi: 10.1021/ar9000058. Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1147–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215–1292. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d.

- 4.Amino acid ligands were first identified as effective ligand scaffolds for Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions during our studies of enantioselective C–H functionalization: Shi B-F, Maugel N, Zhang Y-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4882–4886. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801030. Shi B-F, Zhang Y-H, Lam JK, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:460–461. doi: 10.1021/ja909571z.

- 5.(a) Wang D-H, Engle KM, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. Science. 2010;327:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1182512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:6169–6173. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14137–14151. doi: 10.1021/ja105044s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.More recently, success has also been found using amino acid ligands to promote Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization with directing groups other than carboxylates: Lu Y, Wang D-H, Engle KM, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5916–5921. doi: 10.1021/ja101909t. Dai H-X, Stepan AF, Plummer MS, Zhang Y-H, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7222–7228. doi: 10.1021/ja201708f. Lu Y, Leow D, Wang X, Engle KM, Yu J-Q. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:967–971. Huang C, Chattopadhyay B, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12406–12409. doi: 10.1021/ja204924j.

- 7.Reviews of Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H/R–M cross-coupling from our group: Chen X, Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5094–5115. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273. Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu J-Q. Isr. J. Chem. 2010;50:605–616. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201000038.

- 8.Pyridine ligands have been shown to enhance catalytic turnover in Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions: Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9578–9579. doi: 10.1021/ja035054y. Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Science. 2007;316:1172–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1141956. Zhang J, Khaskin E, Anderson NP, Zavalij PY, Vedernikov AN. Chem. Commun. 2008:3625–3627. doi: 10.1039/b803156h. Zhang Y-H, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5072–5074. doi: 10.1021/ja900327e. Izawa Y, Stahl SS. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:3223–3229. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000771. Izawa Y, Pun D, Stahl SS. Science. 2011;333:209–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1204183. Arnold and Sanford have reported a bidentate NHC-alkoxide ligand that stabilizes cyclopalladated Pd(IV) intermediates but leads to lower activity in Pd(II)/Pd(IV) catalysis: Arnold PL, Sanford MS, Pearson SM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13912–13913. doi: 10.1021/ja905713t. Liu and coworkers have recently reported an example in which an NHC ligand was found to promote a phenol-directed C–H activation/C–O cyclization reaction along a Pd(II)/Pd(0) catalytic cycle: Xiao B, Gong T-J, Liu Z-J, Liu J-H, Luo D-F, Xu J, Liu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9250–9253. doi: 10.1021/ja203335u.

- 9.For a review of ligand-accelerated catalysis, see: Berrisford DJ, Bolm C, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995;34:1059–1070.

- 10.For the initial reports of Pd(II)-mediated C(aryl)–H olefination, see: Moritani I, Fujiwara Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;8:1119–1122. Fujiwara Y, Moritani I, Matsuda M, Teranishi S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:3863–3865.

- 11.Examples of Pd-catalyzed C–H arylation using other modes of catalysis: Campeau L-C, Rousseaux S, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:18020–18021. doi: 10.1021/ja056800x. Daugulis O, Zaitsev VG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4046–4048. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500589. Kalyani D, Deprez NR, Desai LV, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7330–7331. doi: 10.1021/ja051402f.

- 12.For the first reports of Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H/R–M cross-coupling, see: Chen X, Li J-J, Hao X-S, Goodhue CE, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:78–79. doi: 10.1021/ja0570943. Chen X, Goodhue CE, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12634–12635. doi: 10.1021/ja0646747.

- 13.Wang D-H, Mei T-S, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17676–17677. doi: 10.1021/ja806681z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Giri R, Maugel N, Li J-J, Wang D-H, Breazzano SP, Saunders LB, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3510–3511. doi: 10.1021/ja0701614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang D-H, Wasa M, Giri R, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7190–7191. doi: 10.1021/ja801355s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Examples of Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H/R–M cross-coupling from other groups: Yang S, Li B, Wan X, Shi Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6066–6067. doi: 10.1021/ja070767s. Kawai H, Kobayashi Y, Oi S, Inoue Y. Chem. Commun. 2008:1464–1466. doi: 10.1039/b717251f. Ge H, Niphakis MJ, Georg GI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3708–3709. doi: 10.1021/ja710221c. Yang S-D, Sun C-L, Fang Z, Li B-J, Li Y-Z, Shi Z-J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1473–1476. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704619. Zhao J, Zhang Y, Cheng K. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7428–7431. doi: 10.1021/jo801371w. Kirchberg S, Fröhlich R, Studer A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4235–4238. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901072. Zhou H, Xu Y-H, Chung W-J, Loh T-P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5355–5357. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901884. Wei Y, Kan J, Wang M, Su W, Hong M. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3346–3349. doi: 10.1021/ol901200g. Liang Z, Yao B, Zhang Y. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3185–3187. doi: 10.1021/ol101147b. Tredwell MJ, Gulias M, Bremeyer NG, Johansson CCC, Collins BSL, Gaunt MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1076–1079. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005990. Kirchberg S, Tani S, Ueda K, Yamaguchi J, Studer A, Itami K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:2387–2391. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007060. Schnapperelle I, Breitenlechner S, Bach T. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3640–3643. doi: 10.1021/ol201292v. Mochida K, Kawasumi K, Segawa Y, Itami K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10716–10719. doi: 10.1021/ja202975w.

- 16.One elegant approach to improve reactivity with electron-rich substrates has been the use of more electrophilic Pd(II) catalysts: Nishikata T, Abela AR, Huang S, Lipshutz BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4978–4979. doi: 10.1021/ja910973a.

- 17.Aryl carboxylic acid derivatives have been found to be effective organometallic reagent surrogates (via decarboxlation) in Pd(II)-catalyzed R–H/R–CO2H cross-coupling. For leading references, see: Voutchkova A, Copling A, Leadbeater NE, Crabtree RH. Chem. Commun. 2008:6312–6314. doi: 10.1039/b813998a. Wang C, Peil I, Glorius F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4194–4195. doi: 10.1021/ja8100598. Li M, Ge H. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3464–3467. doi: 10.1021/ol1012857.

- 18.Examples of stoichiometric palladacycle/R–M coupling: Murahashi S-I, Tanba Y, Yamamura M, Moritani I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;15:3749–3752. Yamamura M, Moritani I, Murahashi S-I. Chem. Lett. 1974;3:1423–1424. Kasahara A, Izumi T, Maemura M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1977;50:1878–1880. Murahashi S-I, Tamba Y, Yamamura M, Yoshimura N. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:4099–4106. Louie J, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:2359–2361. Dangel BD, Godula K, Youn SW, Sezen B, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11856–11857. doi: 10.1021/ja027311p. In one case, Pd(0) was found to catalyze the intermolecular cross-coupling of 2,4,6-tritert-butylbromobenzene with arylboronic acids via an unusual intervening C(sp3)–H cleavage step following oxidative addition: Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4685–4696. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j.

- 19.Examples of Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H/R–M cross-coupling: Oi S, Fukita S, Inoue Y. Chem. Commun. 1998:2439–2440. Vogler T, Studer A. Org. Lett. 2007;10:129–131. doi: 10.1021/ol702659a.

- 20.Examples of Ru(0)-catalyzed C–H/R–M cross-coupling: Kakiuchi F, Kan S, Igi K, Chatani N, Murai S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1698–1699. doi: 10.1021/ja029273f. Pastine SJ, Gribkov DV, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14220–14221. doi: 10.1021/ja064481j. For Ru(II)-catalyzed C–H/R–M cross-coupling, see: Li H, Wei W, Xu Y, Zhang C, Wan X. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:1497–1499. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04322b.

- 21.In an intriguing recent report, it was found that nucleophilic aryl-centered radicals, generated from arylboronic acids in the presence of catalytic Ag(I) could add to electron-poor heterocycles: Seiple IB, Shun S, Rodriguez RA, Gianatassio R, Fujiwara Y, Sobel AL, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13194–13196. doi: 10.1021/ja1066459.

- 22.In Ref. 13, the substrate scope was largely limited to α-substituted and α,α,-disubstiuted phenylacetic acids, in which palladation is more favorable owing to the Thorpe–Ingold effect. The reaction conditions reported in that reference were as follows: ArBF3K (1.2 equiv.), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), BQ (0.5 equiv.), K2HPO4 (1.5 equiv.), t-BuOH (solvent), 110 °C, O2 (20 atm), 48 h. Under those conditions, many substrates gave unsatisfactory product conversions. Representative examples include 3a (44%), 3d (56%), and 3h (17%). (See Supporting Information for further details.) It is important to note, that thoughout this work, we used 5 mol% Pd(OAc)2.

- 23.In Ref. 13, it was stated that Ag(I) salts completely inhibited the transformation under the reported reaction conditions (given above). That claim does not seem to be true across all reaction conditions.

- 24.For an example of olefin-promoted reductive elimination from Pd(II), see: Kurosawa H, Emoto M, Ohnishi H, Miki K, Kasai N, Tatsumi K, Nakamura A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:6333–6340. BQ has previously been found to promote reductive elimination in a Stille coupling reaction involving allyl halides: Albéniz AC, Espinet P, Martín-Ruiz B. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:2481–2489. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010601)7:11<2481::aid-chem24810>3.0.co;2-2. For the effects of BQ as a ligand in Pd-catalyzed C–H cleavage/C–C bond–forming reactions, see: Boele MDK, van Strijdonck GPF, de Vries AHM, Kamer PCJ, de Vries JG, van Leeuwen PWNM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:1586–1587. doi: 10.1021/ja0176907. Hull KL, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11904–11905. doi: 10.1021/ja074395z.

- 25.For an elegant study of reductive elimination of C2H6 from a [Pd(II)Me2] complex using different methods, including treatment with BQ or Ag(I) salts, see: Lanci MP, Remy MS, Kaminsky W, Mayer JM, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15618–15620. doi: 10.1021/ja905816q.

- 26.Engle KM, Mei T-S, Wang X, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:1478–1491. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.For perspectives on the use of RBF3K reagents, see: Darses S, Genet J-P. Chem. Rev. 2007;108:288–325. doi: 10.1021/cr0509758. Molander GA, Ellis N. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:275–286. doi: 10.1021/ar050199q. Vedejs E, Chapman RW, Fields SC, Lin S, Schrimpf MR. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:3020–3027. Butters M, Harvey JN, Jover J, Lennox AJJ, Lloyd-Jones GC, Murray PM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5156–5160. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001522. For the use of MIDA-boronates, see: Gillis EP, Burke MD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6716–6717. doi: 10.1021/ja0716204.

- 28.For detailed data concerning the effects of PhBF3K/Ag2CO3 loading, see Supporting Information.

- 29.Due to averaging effects, in Figure 1 it appears as if the reaction in the presence of Ac-Ile-OH decelerates after 20 min. However, in individual trials the rate appears to be nearly constant for time points from 20 min until the reactions proceed to completion.

- 30.High conversion with α,α,-disubstituted phenylacetic acids can be obtained using the conditions reported in Ref. 13. With these substrates, the use of mono-N-protected amino acid ligands does not seem to improve the reactivity.

- 31.Reviews of aerobic Pd(II)-catalyzed oxidation chemistry: Stahl SS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3400–3420. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630. Stoltz BM. Chem. Lett. 2004;33:362–367. Gligorich KM, Sigman MS. Chem. Commun. 2009:3854–3867. doi: 10.1039/b902868d.

- 32.Although at the present time high pressure O2 poses a safety risk when used at elevated termperatures, the advent of flow technology may soon render this approach more tenable. For leading references, see: Ye X, Johnson MD, Diao T, Yates MH, Stahl SS. Green Chem. 2010;12:1180–1186. doi: 10.1039/c0gc00106f. Murphy ER, Martinelli JR, Zaborenko N, Buchwald SL, Jensen KF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:1734–1737. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604175. O’Brien M, Baxendale IR, Ley SV. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1596–1598. doi: 10.1021/ol100322t. Saaby S, Knudsen KR, Ladlow M, Ley SV. Chem. Comm. 2005:2909–2911. doi: 10.1039/b504854k.

- 33.Sale DA, Engle KM, Yu J-Q, Blackmond DG. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 34.We have found Ac-Ile-OH-bound Pd(II) complexes to be difficult to characterize due to their poor solubility in non-polar solvents. The use of more polar coordinating solvents introduces the possibility that a solvent molecule could displace a ligand on Pd(II) and/or cause disaggregation of any oligomeric Pd(II) species. Furthermore, interpretation of the spectral data for multinuclear Ac-Ile-OH-bound Pd(II) complexes tends to be challenging owing to the possibility of cis/transisomerism.

- 35.We tested the activity of one amorphous "[Pd(Ac-Ile-OH)(OAc)]" complex and found that using 5 mol% catalyst with no additional ligand under otherwise identical reaction conditions to those depicted in Table 5 gave 85% conversion after 2 h. This "[Pd(Ac-Ile-OH)(OAc)]" complex was synthesized using the following procedure: To a flame-dried flask 20 mL round bottom flask containing a magnetic stir bar were added Pd(OAc)2 (0.057g, 0.25mmol), Ac-Ile-OH (0.043g, 0.25mmol), and α,α,α-trifluorotoluene (4 mL). The resulting mixture was capped and allowed to stir at ambient temperature for 4 h. Solvent was removed in vacuo, giving amorphous “[Pd(Ac-Ile-OH)(OAc)]” as an dark orange powder in quantitative yield. It showed broad peaks in its NMR spectra (in CDCl3), and was not further characterized.

- 36.Examples of countercation-promoted, carboxylated-directed Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization from our group: Mei T-S, Giri R, Maugel N, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5215–5219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705613. Giri R, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14082–14083. doi: 10.1021/ja8063827. Mei T-S, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3140–3143. doi: 10.1021/ol1010483. Zhang Y-H, Shi B-F, Yu J-Q. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:6097–6100. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902262. Zhang Y-H, Yu J-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14654–14655. doi: 10.1021/ja907198n.

- 37.Examples of carboxylate-directed Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions from other groups: Miura M, Tsuda T, Satoh T, Pivsa-Art S, Nomura M. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:5211–5215. Chiong HA, Pham Q-N, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9879–9884. doi: 10.1021/ja071845e. Wang C, Rakshit S, Glorius F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14006–14008. doi: 10.1021/ja106130r. For a review, see: Satoh T, Miura M. Synthesis. 2010:3395–3409. Carboxylate-directed ortho-thallation is a known means of generating organothallium compounds which can be used in Pd(II)-catalyzed functionalization reactions: Larock RC, Fellows CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:1900–1907.

- 38.For a review of the complex-induced proximity effect (CIPE), see: Beak P, Snieckus V. Acc. Chem. Res. 1982;15:306–312.

- 39.It is important to clarify that if the C–H cleavage step is not rate-limiting under either of the two reaction conditions (i.e., in the presence of absence of Ac-Ile-OH), then the relative reaction rates would actually be reflective of the energy barriers for other elementary steps in the catalytic cycle. Regardless of what the rate-determining step is, the qualitative observation of high reactivity with electron-poor substrates is difficult to explain were one to invoke a traditional electrophilic palladation mechanism.

- 40.In Ref. 5c, we used the term “proton abstraction”. The term “concerted metallation/deprotonation” is more commonly used in the literature, so we use it here to convey the same meaning.

- 41.For studies concerning the mechanistic aspects C–H cleavage in Pd(II)-catalyzed reactions, see: Ryabov AD, Sakodinskaya IK, Yatsimirsky AK. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1985:2629–2638. Canty AJ, van Koten G. Acc. Chem. Res. 1995;28:406–413. Tunge JA, Foresee LN. Organometallics. 2005;24:6440–6444. For experimental and computational evidence of concerted metallation/deprotonation, see: Gómez M, Granell J, Martinez M. Organometallics. 1997;16:2539–2546. Gómez M, Granell J, Martinez M. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1998:37–44. Biswas B, Sugimoto M, Sakaki S. Organometallics. 2000;19:3895–3908. Davies DL, Donald SMA, Macgregor SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13754–13755. doi: 10.1021/ja052047w. Roiban G-D, Serrano E, Soler T, Aullón G, Grosu I, Cativiela C, Martínez M, Urriolabeitia EP. Inorg. Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ic200564d. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:8132–8143. doi: 10.1021/ic200564d. For a reviews of carboxylate-assisted C–H cleavage in transition metal catalysis, see: Ackermann L. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1315–1345. doi: 10.1021/cr100412j. Lapointe D, Fagnou K. Chem. Lett. 2010;39:1118–1126.

- 42.Even still, 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixtures revealed substantial homocoupling between the ArBF3K reagents (and the ArBPin reagents) under our optimized conditions.

- 43.For an early report of Ag(I)’s efficacy in promoting transmetallation in Pd(0)-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions, see: Uenishi J, Beau JM, Armstrong RW, Kishi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:4756–4758.

- 44.To clarify, we noted previously that when Ag(I) is used as the reoxidant for C–H/R–BX2 cross-coupling, BQ is not required as was used only to improve reproducibility. In the case of reoxidation with O2, BQ is required for catalysis.

- 45.(a) Keith JM, Nielsen RJ, Oxgaard J, Goddard WA., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13172–13179. doi: 10.1021/ja043094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keith JM, Nielsen RJ, Oxgaard J, Goddard WA., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13172–13179. doi: 10.1021/ja043094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Konnick MM, Gandhi BA, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:2904–2907. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Keith JM, Muller RP, Kemp RA, Goldberg KI, Goddard WA, III, Oxgaard J. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:9631–9633. doi: 10.1021/ic061392z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Popp BV, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4410–4422. doi: 10.1021/ja069037v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Keith JM, Goddard WA, III, Oxgaard J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10361–10369. doi: 10.1021/ja070462d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Konnick MM, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5753–5762. doi: 10.1021/ja7112504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Popp BV, Stahl SS. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:2915–2922. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Keith JM, Goddard WA., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1416–1425. doi: 10.1021/ja8040459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Konnick MM, Decharin N, Popp BV, Stahl SS. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:326–330. [Google Scholar]; (k) Decharin N, Popp BV, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13268–13271. doi: 10.1021/ja204989p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Decharin N, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5732–5735. doi: 10.1021/ja200957n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sims JW, Schmidt EW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11149–11155. doi: 10.1021/ja803078z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.