Abstract

Objectives. To assess the validity and reliability of an instrument to measure pharmacy students’ attitudes toward physician-pharmacist collaboration, and compare those attitudes to the attitudes of medical students.

Methods. One hundred sixty-six first-year pharmacy students and 77 first-year medical students at Midwestern University completed the Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration.

Results. Findings confirmed the validity and reliability of the Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration in pharmacy students, as observed previously for medical students. Pharmacy students’ mean score was significantly higher (56.6 ± 7.2) than that of medical students (52.0 ± 6.1). Maximum likelihood factoring confirmed the 3-factor solution of responsibility and accountability, shared authority, and interdisciplinary education for pharmacy students.

Conclusions. The Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration can be used for the assessment of interdisciplinary educational programs, for patient outcome assessment of interprofessional collaboration, and for group comparisons. Findings that pharmacy students expressed more positive attitudes toward collaboration than medical students have implications for interdisciplinary education.

Keywords: interprofessional collaboration, interprofessional education, health professions students, reliability, validity, psychometrics, attitudes

INTRODUCTION

Interprofessional collaboration in patient care among US health care professionals began in World War II when medical, surgical, and nursing teams worked together to treat injured soldiers.1 Health care providers now consider collaboration and teamwork to be an important component of professionalism2 leading to greater patient safety1 and better patient outcomes.3-9 Physician-pharmacist collaboration results in improved patient self-care skills, fewer drug interactions10,11 and medication errors,12 and more cost-effective use of medication,13 all of which lead to more effective drug therapy and better patient outcomes.

Interdisciplinary education in medical and pharmacy colleges and schools is designed to enhance the skills that physicians and pharmacists will need to function in interprofessional health care teams.14 These educational efforts are to ensure that all health care practitioners effectively use their specialized training and expertise to optimize patient care and improve therapeutic outcomes. For example, medical and pharmacy students at Midwestern University are taught together in several basic science and communications courses and in an introductory course entitled Health Care Issues. A collaborative relationship between pharmacists and physicians is needed more than ever because of the rapid advancements in medical and pharmaceutical sciences, occurrence of complex drug interactions, increased costs of drug-related morbidity, greater possibility of medical errors, and rapidly rising health care costs. Schellens and colleagues stated: “In view of its increasing complexity, rational and tailored drug therapy cannot be implemented in its full width when the discipline is applied only by physicians.”15

The characteristics desirable in health care professional collaborations are emerging. Coluciio and Maguire described professional collaboration in terms of a “joint communication and decision-making process…with the goal of meeting the patient's wellness and illness needs as best as possible, while respecting the unique qualities and abilities of both professionals.”16 Baggs and Schmitt point out that collaborative relationships require “…cooperatively working together, sharing responsibilities for solving problems and making decisions to formulate and carry out plans for patient care.”17 Key components of these and most other descriptions of interprofessional teamwork and collaboration include accountability, communication, education, and shared decisions and responsibilities.

Despite the importance of a collaborative relationship between physicians and pharmacists, no report was found in the literature of a psychometrically sound instrument to measure interprofessional attitudes and perceptions in medical and pharmacy students as well as physicians and pharmacists. Although some instruments are available for measuring collaborative relationships between physicians and pharmacists, none can be applied to both practitioners and students for comparative research. For example, the Physician/Pharmacist Collaboration Index was originally developed to assess physicians’ perspectives about collaborative relationships with pharmacists.18 The scale contains 14 items, and a typical item is: “This pharmacist is credible.” There is a different version of this instrument that was adapted to assess pharmacists’ perspectives about collaboration with physicians.14 The corresponding item in that instrument reads: “This physician is credible.”

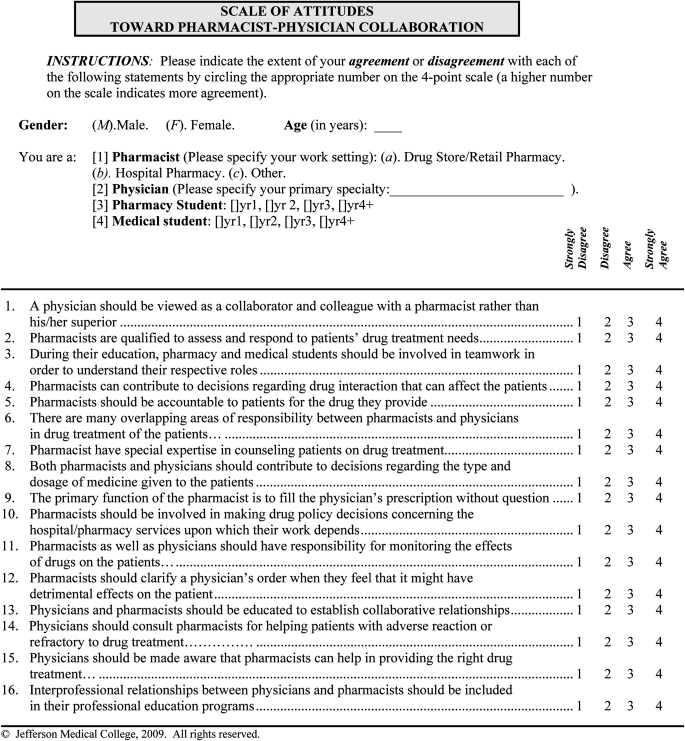

Hence, there was a need for a single psychometrically sound instrument to measure attitudes toward physician-pharmacist collaborative relationships in both physicians and pharmacists, and in students of these professions. Such an instrument was needed for outcome assessments of interdisciplinary educational programs and for the evaluation of clinical outcomes resulting from interprofessional collaboration. In response to this need, the Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration (SATP2C) was developed (Appendix 1). The step-by-step development of the scale, a pilot study of its face and content validities, and preliminary psychometrics with samples of physicians’ and pharmacists’ responses have been reported.19 Psychometrics of the scale (eg, construct validity, reliability) in medical students also have been studied (M. Hojat, PhD, et al, unpublished data, 2011).

This study was designed to assess the validity and reliability of an instrument to measure pharmacy students’ attitudes toward collaborative relationships and to examine differences in collaborative attitudes between pharmacy and medical students. This study was found to fulfill the criteria for exemption by the Midwestern University Institutional Review Board.

METHODS

Research participants at Midwestern University included 166 first-year pharmacy students of the Chicago College of Pharmacy and 77 first-year medical students of the Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine. The SATP2C includes 16 items, each answered on a 4-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree). The possible range of scores is from 16 to 64, with a higher score indicating a more positive attitude toward collaborative relationships between physicians and pharmacists.

The SATP2C was administered to pharmacy students at the end of a required workshop on January 13, 2011, and to medical students at the end of an optional workshop session on February 3, 2011. The survey instrument required less than 10 minutes to complete. Students did not receive prior study information pertinent to the survey instrument. Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous, so no consent was sought; however, students were asked to specify their gender.

Correlational methods were used to examine the item-total score correlations. Differences in scores on attitudes toward collaboration between groups of students were examined using t tests. Maximum likelihood factoring method was used to confirm the factorial structure of the instrument. Cronbach's coefficient alpha was calculated to provide evidence in support of the internal consistency and reliability of the scale. The Statistical Analysis System (SAS, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

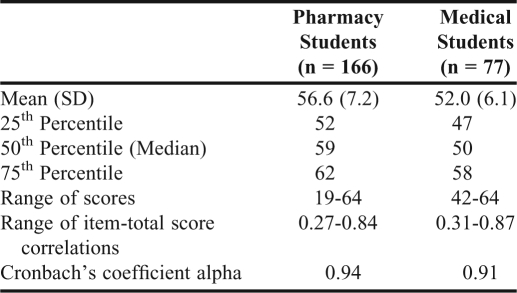

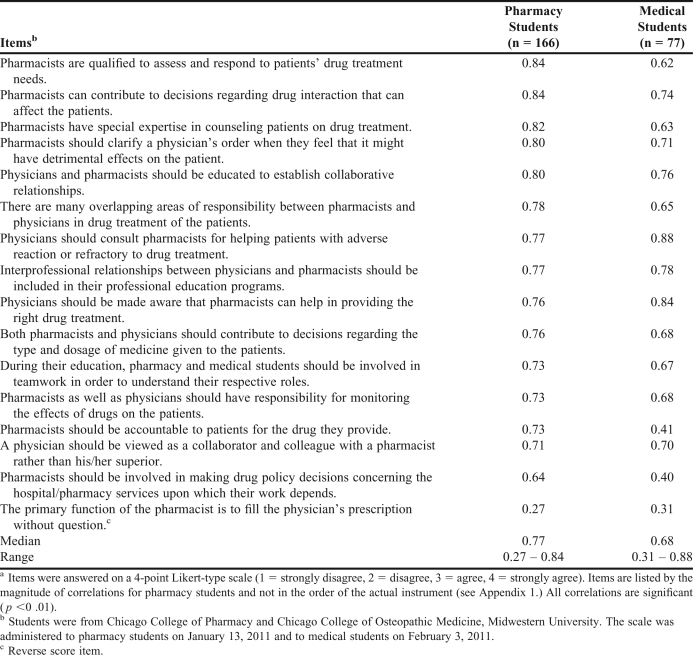

Completed survey instruments were returned by 166 of 209 first-year pharmacy students (80% response rate) and 77 of 202 first-year medical students (38% response rate). Descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for the SATP2C for pharmacy and medical students are reported in Table 1. The mean scores for pharmacy and medical students were 56.6 ± 7.2, and 52.0 ± 6.1, respectively, and Cronbach's coefficients alpha were 0.94 and 0.91. The mean SATP2C score of pharmacy students was significantly higher than the mean score of medical students (p < 0.01). All corrected item-total score correlations for each group of students were positive and significant (p < 0.01; Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration

Table 2.

Item-Total Score Correlations for the Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration for Pharmacy and Medical Studentsa

In a previous factor analytic study of the SATP2C with medical students (M. Hojat, PhD, et al, unpublished data, 2011), 3 reliable factors emerged: responsibility and accountability, shared authority, and interdisciplinary education. In the present study we used data for pharmacy students to examine whether the 3-factor model would be sufficient to explain the underlying structure of the scale. We did not perform confirmatory factor analysis for medical students because of the insufficient sample size for that type of statistical analysis. Results of the maximum likelihood factoring indicated that the 3-factor model could sufficiently explain the underlying structure of the scale in pharmacy students (p < 0.05). A 4-factor model was rejected (p = 0.30).

Of the 166 pharmacy students who completed the survey instrument, 92 women and 73 men specified their gender. Among the 77 medical students, 31 women and 44 men provided gender information. These gender ratios are similar to those for the entire corresponding classes, which were 57% and 45% female, respectively. No significant gender differences in mean scores on the SATP2C were observed. In pharmacy students, mean scores were 56.8 ± 7.0, and 56.3 ± 7.4 for men and women, respectively (p = 0.64), and in medical students the mean scores were 51.5 ± 5.5 and 53.1 ± 6.9 for men and women, respectively, (p = 0.25).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the validity and reliability of the SATP2C in determining pharmacy students’ attitudes, and further supports use of the scale for determining medical students’ attitudes. The magnitudes of reliability coefficients were all in the acceptable range for psychological tests, supporting the internal consistency and reliability of the instrument.

The significant, positive item-total score correlations for each item in both groups indicates that each item contributed significantly to the total scores of the scale. Confirmation of previously emerged factor structure indicates that the underlying constructs of the SATP2C is reliable and valid considering that the 3 factors of responsibility and accountability, shared authority, and interdisciplinary education have been described as important elements of collaborative relationships among health professionals.3-7

More positive attitudes toward collaboration among pharmacy students than among medical students confirms the principle of least interest proposed by Waller and Hill in the context of family relations.20 According to this principle, those who traditionally have been in a more powerful position are less likely to express eagerness for collaborative relationships with others whom they consider to be lower in the power hierarchy. This principle has been confirmed in several studies. For example, in a multi-national study, physicians in 4 countries (Israel, Italy, Mexico, and the United States) scored lower than nurses on a scale of attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration.21 Similar results have been reported by Garber and colleagues,22 Strechi,23 Jones and colleagues (comparing anesthesiologist and nurse anesthetists) ,24,25 and by Hansson and colleagues (in a study with Swedish general practitioners and nurses).26 However, 1 study in Turkey reported more positive attitudes toward collaboration among medical students than among nursing students.27 It will be interesting to learn whether medical and pharmacy students’ attitudes toward collaboration converge as their training proceeds.

A multi-disciplinary study on attitudes toward interdisciplinary education and professional teamwork that compared medical, pharmacy, nursing, and social work students, found that pharmacy and social work students expressed more positive attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration than medical students.28 Our finding that medical students scored lower on their attitudes toward collaborative relationship than pharmacy students has implications for interdisciplinary education and interprofessional collaboration. More research is needed to confirm our results in students and practitioners at multiple institutions. Because of the importance of teamwork and collaboration among health professionals to patient's safety,29 targeted educational remedies are needed for the development of more positive and mutually respectful attitudes in these areas among health care professionals.

Although this study benefits from using samples of students in 2 health care professions, the single-institution nature of this study, convenience sampling, small sample size, and low response rates (particularly of medical students) may have affected the external validity of the instrument and limited generalization of the findings. In addition, administering the survey to pharmacy students in a required workshop and to medical students in an optional one could have biased our results. Despite these limitations, the findings in support of the measurement properties of the SATP2C are encouraging.

CONCLUSIONS

The SATP2C is a validated measure of attitudes toward interprofessional collaborative practice, defined as a situation “when multiple health workers [including physicians and pharmacists] from different professional backgrounds provide comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, careers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings.”30 The SATP2C has the potential to be used in the assessments of interdisciplinary educational programs where “students from 2 or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.”30 Also, the SATP2C can be used in examining group differences in attitudes toward physician-pharmacist collaboration, and in empirical research on clinical outcomes of teamwork and collaboration among health care professionals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Paulette Burdick for her administrative help in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin D. Some historical notes on interdisciplinary and interprofessional education and practice in the USA. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(suppl 1):23–37. doi: 10.1080/13561820701594728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veloski J, Hojat M. Measuring specific elements of professionalism: empathy, teamwork, and lifelong learning. In: Stern TD, editor. Measuring Medical Professionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 117–145. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagin CM. Collaboration between nurses and physicians: no longer a choice. Acad Med. 1992;67(5):295–303. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papa PA, Rector C, Stone C. Interdisciplinary collaborative training for school-based health professionals. J Sch Health. 1998;68(10):415–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemmer TP, Spuhler VJ, Berwick DM, Nolan TW. Cooperation: the foundation of improvement. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(12):1004–1009. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_part_1-199806150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulton BC, West MA. Effective multidisciplinary teamwork in primary health care. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(6):918–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18060918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nkansah NT, Brewer JM, Connors R, Shermock KM. Clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes mellitus receiving medication management by pharmacists in an urban private physician practice. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008;65(2):145–149. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter BL, Bergus GR, Dawson JD, et al. A cluster randomized trial to evaluate physician/pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10(4):260–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiel PJ, McCord AD. Pharmacist impact on clinical outcomes in a diabetes disease management program via collaborative practice. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(11):1828–1832. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonough RP, Doucette WR. Dynamics of pharmaceutical care: developing collaborative working relationships between pharmacists and physicians. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41(5):682–692. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock KA, Doucette WR. Collaborative working relationships between pharmacists and physicians: an exploratory study. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2004;44(3):358–365. doi: 10.1331/154434504323063995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sweeney MA. Physician-pharmacist collaboration: a millennial paradigm to reduce medication errors. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2002;102(12):678–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies JG, Horne R, Bennett J, Stott R. Doctors, pharmacists and the prescribing process. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 1994;52(4):167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zillich AJ, Milchak JL, Carter BL, Doucette WR. Utility of a questionnaire to measure physician-pharmacist collaborative relationships. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2006;46(4):453–458. doi: 10.1331/154434506778073592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schellens JHM, Grouls R, Guchelaar HJ, et al. The Dutch model for clinical pharmacology: collaboration between physician- and pharmacist-clinical pharmacologist. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(1):146–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coluccio M, Maguire P. Collaborative practice: becoming a reality through primary nursing. Nurs Adm Q. 1983;7(4):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braggs JG, Schmitt MH. Collaboration between nurses and physicians about care decisions. Image J Nurs Sch. 1988;20(3):145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zillich AJ, Doucette WR, Carter BL, Kreiter CD. Development and initial validation of an instrument to measure physician-pharmacist collaboration from the physician perspective. Value Health. 2005;8(1):59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hojat M, Gonnella JS. An instrument for measuring pharmacist and physician attitudes toward collaboration: preliminary psychometric data. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(1):66–72. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.483368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller W, Hill R. The Family: A Dynamic Interpretation. Dryden; New York: 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, et al. Comparisons of American, Israeli, Italian and Mexican physicians and nurses on the total and factor scores of the Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Nurse Collaborative Relationships. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(4):427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garber JS, Madigan EA, Click ER, Fitzpatrick JJ. Attitudes toward collaboration and servant leadership among nurses, physicians and residents. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(4):331–340. doi: 10.1080/13561820902886253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterchi SL. Perceptions that affect physician-nurse collaboration in the preoperative setting. AORN J. 2007;86(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones TS, Fitzpatrick JJ. CRNA-physician collaboration in anesthesia. AANA J. 2009;77(6):431–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor CL. Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration in anesthesia. AANA J. 2009;77(5):343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansson A, Arvemo T, Marklund B, Gedda B, Mattsson B. Working together- primary care doctors’ and nurses’ attitudes to collaboration. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(1):78–85. doi: 10.1177/1403494809347405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardahan M, Akcasu B, Engin E. Professional collaboration in students of medicine faculty and school of nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(4):350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J, Flynn K. Attitudes of health sciences students toward interprofessional teamwork and education. Learn Health Soc Care. 2008;7(3):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weller J, Frengley R, Torrie J, et al. Evaluation of an instrument to measure teamwork in multidisciplinary critical care teams. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(3):216–222. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. 2010. http://who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/index.html. Accessed October 6, 2011. [PubMed]