Abstract

Objective. To cross-validate an instrument to measure behavioral aspects of professionalism in pharmacy students using a rating scale that minimizes ceiling effects.

Methods. Seven institutions collaborated to create a 33-item assessment tool that included 5 domains of professionalism: (1) Reliability, Responsibility and Accountability; (2) Lifelong Learning and Adaptability; (3) Relationships with Others; (4) Upholding Principles of Integrity and Respect; and (5) Citizenship and Professional Engagement. Each item was rated based on 5 levels of competency which were aligned with a modified Miller's Taxonomy (Knows, Knows How, Shows, Shows How and Does, and Teaches).

Results. Factor analyses confirmed the presence of 5 domains for professionalism. The factor analyses from the 7-school pilot study demonstrated that professionalism items were good fits within each of the 5 domains.

Conclusions. Based on a multi-institutional pilot study, data from the Professionalism Assessment Tool (PAT), provide evidence for internal validity and reliability. Use of the tool by external evaluators should be explored in future research.

Keywords: professionalism, assessment, self-assessment, survey, factor analysis, cross-validation

INTRODUCTION

A key component in the practice of pharmacy is the pharmacist's demonstration of professional attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, professionalism education should be a critical part of any doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) lists professionalism as an area of emphasis in their accreditation standards and guidelines.1

Professionalism has been defined in contemporary pharmacy literature as possession and/or demonstration of structural, attitudinal and behavioral attributes of a profession and its members.”2 Professionalism also can be defined as a “set of core values that includes altruism/service, caring, honor, integrity, duty and others.”3 While these definitions provide practitioners and educators a sense of the fundamental nature of professionalism, they are not methods for measuring professionalism in our students or practicing pharmacists.

Professionalism can be challenging to assess and there are numerous barriers to measuring it.4 Definitions are more abstract than concrete. Furthermore, professionalism is somewhat specific to the context in which the pharmacist or trainee is practicing (eg, a student on a practice experience in a large, urban academic health center vs. a classroom setting). Also, there is reluctance to address unprofessional behaviors, however minor.4 Finally, it can be difficult to garner accurate measures of concepts such as professionalism because survey takers tend to rate themselves at or near the top of the scale on every item.5 This ceiling effect of measurement limits the usefulness of the instrument for measuring change over time.6 Another difficulty associated with measuring professionalism is that professionalism is based on a set of internally held values that are exhibited and measured through behaviors; ie, professionalism can be viewed as both attitudinal (internal to the practitioner) and behavioral (externally exhibited to the world by the practitioner). Attitudinal measures of professionalism may not address outward behaviors, and behavioral measures may not address internally held values related to professionalism.3

While there are many publications on professionalism in pharmacy, relatively few papers report on the formal curriculum associated with teaching professionalism or assessing students’ acquisition of professionalism.7 Only 3 articles report on the development of tools to measure professionalism in pharmacy students. Hammer and colleagues developed an instrument to be used by preceptors to measure the behavioral aspects of professionalism based on items collected from student evaluation forms.2 The instrument developed by Chisholm and colleagues is based on the American Board of Internal Medicine's (ABIM's) 6 tenets of professionalism and measures attitudinal aspects of professionalism by means of self-assessment.8 Lerkiatbundit reported on the development of an attitudinal self-assessment of professionalism,9 and on the validation of this instrument to measure change in professional attitudes over time.10 This instrument contains 6 subscales and is based on earlier works by Schack and Helper that measured attitudinal professionalism in pharmacists.11

Lynch and colleagues reviewed the literature on professionalism in medicine and recommended a set of best practices for professionalism assessment.12 The recommendations include formative assessment of learners early on and frequent in the curriculum, and conducting assessments in different settings and by multiple assessors using multiple methods. They also recommended that existing professionalism assessments should be improved rather than replaced by newly created instruments or tools. Veloski and colleagues reviewed the medical literature on professionalism instruments and reported that few published instruments address the 3 fundamental measurement properties: content validity, reliability, and practicality.13

Several of the colleges and schools participating in this project had attempted to measure professionalism using the tools described here and discovered that students tended to rate themselves at the top of the measurement scales regardless of when they were being assessed.6 The ceiling effects of these instruments limited their usefulness in capturing the development of professionalism over time and provided little in the way of useful data to inform curricular change. For these reasons, we sought to work together to build on knowledge gained from previous instruments to develop a new instrument. The researchers had access to student populations at 7 institutions, enabling robust instrument validation, and a multi-institutional pilot study was conducted to establish reliability and validity of the developed instrument. The primary aim of this project was to develop and cross-validate an instrument that measures behavioral professionalism in pharmacy students using a rating scale that minimizes response ceiling effects.

METHODS

A search of the medical literature yielded 3 tools for measuring behavioral aspects of professionalism that were used to inform the development of the instrument presented here. Arnold and colleagues developed a self-assessment instrument based on the ABIM definition of professionalism.14 This instrument focuses on specific negative (unprofessional) behaviors associated with the ABIM domains of professionalism. DeHaas and colleagues developed the Amsterdam Attitude and Communication Scale (AACS).15 This 9-item behavioral scale used by preceptors to evaluate trainees is time efficient but not comprehensive. Papadakis and colleagues developed the Physicianship Evaluation Form.16 In this instrument, 20 items, over 4 domains are used by preceptors to assess student professionalism. This behavioral instrument is more comprehensive than the AACS tool with respect to the possible domains of professionalism but does not include the domain of engagement with one's profession.

A group of researchers who hold administrative positions at 7 colleges and schools of pharmacy (Purdue University, University of Illinois-Chicago, University of Iowa, University of Michigan, University of Minnesota, The Ohio State University, and the University of Wisconsin) collaborated to capitalize on collective assessment knowledge and the ability to access a large student population. The group goal was to identify a suitable means of measuring professionalism in students and assessing the adequacy of professionalism content within curricula. Major forces driving this goal were the need to meet accreditation standards, improve curricular reform agendas and the desire to use a tool with compelling validity evidence.

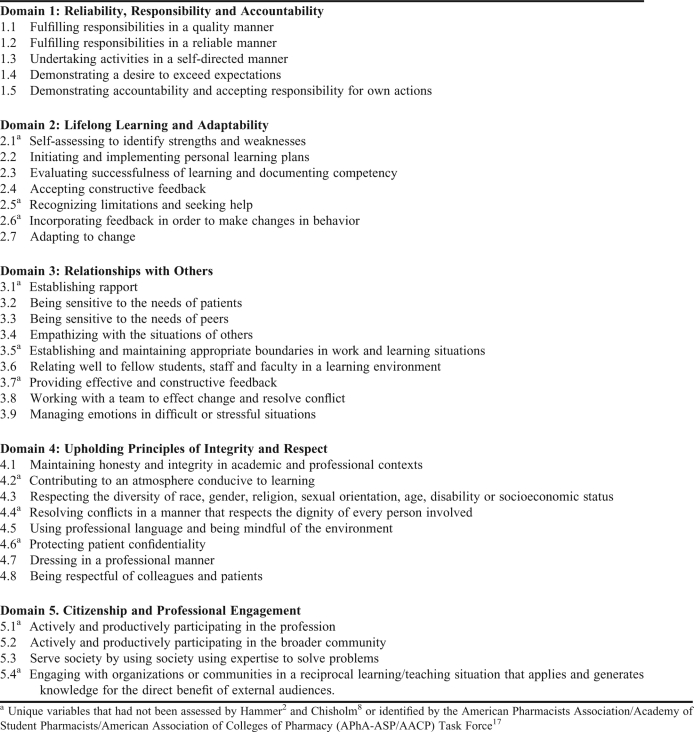

After reviewing the literature, the group embarked on a process of creating the Professionalism Assessment Tool (PAT). The variables to be assessed were derived from the Physicianship Evaluation Form16 because of its alignment with variables identified in American Pharmacists Association/Academy of Student Pharmacists/American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (APhA-ASP/AACP) white paper on student professionalism, as well as those assessed by Hammer and Chisholm.2,8,17 The major domains in the Physicianship Evaluation Form include reliability and responsibility, self-improvement and adaptability, relationships with others, and upholding principles. The researchers revised the individual items to make them applicable to pharmacy education and added a fifth domain: citizenship and professional engagement. This domain was informed by the APhA-ASP/AACP white paper on student professionalism and contains critical missing items related to serving society and engaging in the profession of pharmacy. Two questions were developed for the conclusion of the instrument: “Of the 5 domains, which do you believe is your area of professional strength?” and “Of the 5 domains, which do you believe is an area for improvement?”

The items from the new instrument were mapped to items in instruments developed by Hammer2 and Chisholm,8 as well as to the traits of a professional described by the APhA-ASP/AACP white paper on student professionalism.17 They also were reviewed for face validity by pharmacy faculty and students at each institution. Table 1 presents the instrument and denotes unique items and concepts not identified by these 3 sources, including those developed for the Citizenship and Professionalism domain as well as original items from Papadakis.16

Table 1.

Variables Assessed in the Professionalism Assessment Tool

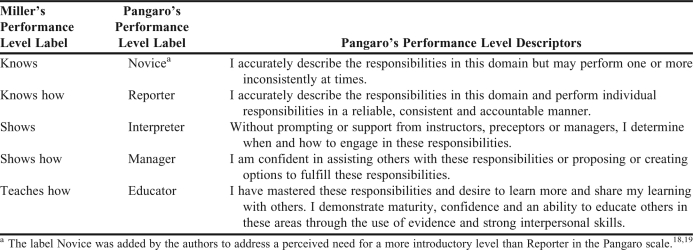

A 5-point scale was developed using descriptors suggested by Pangaro.18 Faculty members involved with professionalism instruction at each institution reviewed the rating scale. Next, each performance level label of the rating system was aligned with a modification of Miller's Framework for Clinical Assessment,19 which had been used by some participating institutions in other assessment projects. The intuitiveness and familiarity of this framework was considered an asset. The levels included knows, knows how, shows, shows how, and teaches. The final rating scale used Miller's performance level labels and Pangaro's performance level descriptors (Table 2).18,19

Table 2.

Derivation of the Professionalism Assessment Tool Rating Scale's Performance Level Labels and Descriptors

An initial test was conducted by 3 of the colleges of pharmacy (UIC, OSU,WI) in the spring of 2009. Cronbach's alpha was used to assess reliability. The combined data for 3 schools achieved an alpha of 0.767. Considered in conjunction with input from participating colleges and schools on the usefulness of the data, this finding was deemed sufficiently strong, to warrant expansion of the instrument testing to all 7 colleges and schools. Following the initial testing, Pangaro's labels were removed, leaving only Miller's labels for respondents to use in self-rating.

The 7 colleges and schools of pharmacy that agreed to participate in the evaluation of this new instrument included Purdue University, Ohio State University, University of Illinois-Chicago, University of Iowa, University of Minnesota, University of Wisconsin and University of Kansas. University of Michigan participated in the PAT development but not the data collection. The instrument was administered to PharmD students in their first or third year during spring 2010. These 2 groups of students were selected to provide a baseline (first-year) measurement and an assessment during their third year, after having had more comprehensive exposure to the curriculum. Paper survey instruments were administered during class time or scheduled meeting times for students in which the entire cohorts were present. Participation was completely voluntary and no attempts were made to capture nonresponders or students absent on the day of the administration. This study was approved at each participating college's or school's institutional review board. The data collection for the PAT were included as part of a larger project (results to be reported elsewhere), which also included a survey instrument to measure student engagement.

A total of 1202 first- and third-year students at the 7 institutions completed the 33-item PAT. A data screening analysis was completed to remove cases containing incomplete or suspect data. Seventy-five cases were removed from the analysis because of missing data on at least 1 item, and another 49 cases were removed because participants failed to finish the inventory. Because the inventory was administered at the same time as other assessments, the authors expected to receive incomplete survey instruments.

Thirty-one additional cases were removed because of identical answers on all inventory questions and reported agreement on strongest and weakest domains. Removal of these unreliable measures of student ability from the analysis increased the validity of the structure of the PAT. For example, if a participant selected the fourth option (shows how) for all 33 items as well as for 2 additional items (“Of the 5 domains, which do you believe is your area of professional strength?” and “Of the 5 domains, which do you believe is an area for improvement?”), that participant's survey responses were removed from the analysis.

After these exclusions, 1047 cases were available for analysis. The data then were randomly split into 2 separate data sets, which were used for analysis in an attempt to cross-validate the structure of PAT. Cross-validation is a recommended step in which the stability of factors is tested.20 The first set of data was used for an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). To determine whether an EFA of the data would be appropriate, a measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity were conducted. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was used to determine whether the variables within the data set shared a common factor with other variables. Bartlett's test of sphericity identifies relationships among the instrument's variables. Rejection of the null hypothesis suggested the existence of some relationships between variables, indicating that a factor analysis would be appropriate.

With no constraints on the data, EFA is used to discover patterns in the factor structure and to examine the internal reliability. Using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (version 17.0, SPSS Inc. Chicago), an exploratory factor analysis with promax rotation was used to determine the underlying structure of students’ professionalism self-ratings on the 33-item inventory. A promax rotation is an oblique rotation method used to find patterns in large correlated data sets. The rotation was used to improve the meaningfulness, reliability, and reproducibility of factors.21 Factors were included in the solution only if eigenvalues were greater than 1. Items with loadings greater than 0.5 and cross loadings less than 0.3 were considered for inclusion in the analysis.22

A reliability analysis also was conducted on the factors suggested by the EFA. Reliability was calculated using the KR-20 statistic, which determines the internal consistency of dichotomous choices. Values can range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating that the PAT would likely correlate higher with alternative forms of the same measure of professionalism. The KR-20 reliability is an index of reproducibility, not a measure of quality. George and Mallery have suggested the following scale: KR-20 values of greater than 0.9 = excellent, values greater than 0.8 but less than 0.9 = good, values greater than 0.7 but less than 0.8 = acceptable, values greater than 0.6 but less than 0.7 = questionable, values greater than 0.5 but less than 0.6 = poor, and values less than 0.5 = unacceptable.23

Nunnally and Bernstein interpret a reliability coefficient of 0.70 as acceptable for early stages of research.22 These authors also suggest that basic research should require test scores to have a reliability coefficient of 0.80 or higher, and that if important decisions are to be based on test scores, a reliability coefficient of 0.90 is the minimum, with 0.95 or higher being the desirable standard.24

After a structure for the PAT was hypothesized using the EFA, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the second data set. CFA can test the hypothesis that a relationship exists between the observed variables and their underlying factors if the number of factors can be specified. The factor structure was tested using M-plus software, version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén Los Angeles).

The fit of the model was analyzed using the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Standard Root Mean Residual (SRMR) fit indices. Several indices can be used to determine fit of a model, but many of these indices are highly correlated.25 Hu and Bentler suggest the use of RMSEA and SRMR, which are not highly correlated. RMSEA values less than 0.06 typically indicate a good model fit, and values less than 0.08 suggest a reasonable fit.25 SRMR values less than 0.05 indicate a good model-data fit, while values less than 0.10 suggest an acceptable model-data fit.26

RESULTS

The KMO test result for the data was 0.964, suggesting that the sample was appropriate for completing a factor analysis. The data used showed that Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant, χ2 (528) = 15761.7, p < 0.001, rejecting the null hypothesis of joint correlation across the 2 (alpha = 0.05) and suggesting a strong relationship among variables. Based on the results of these 2 analyses, an exploratory factor analysis with a promax rotation was completed using the same data.

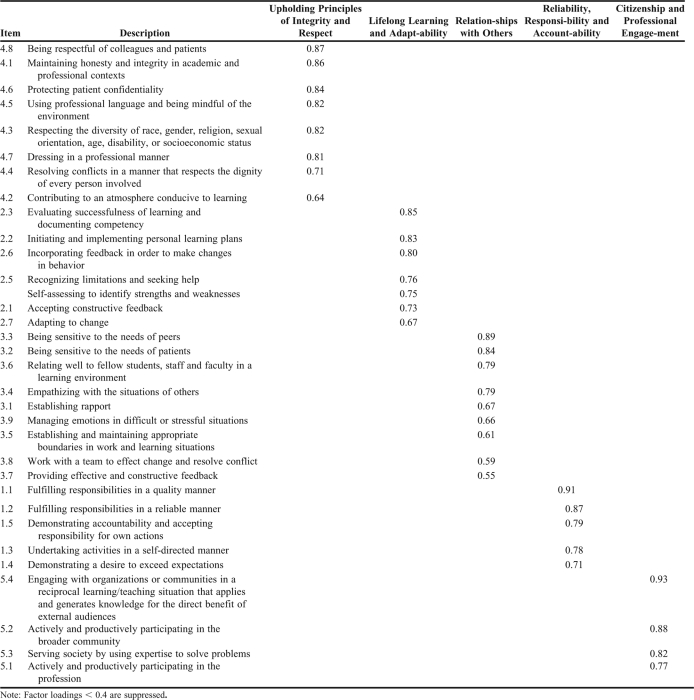

All 33 factors loaded over 0.5 on only 1 factor and did not show factor loadings over 0.3 on other factors. All 33 items loaded to their expected factors, suggesting that no changes to the PAT were needed. Table 3 displays the pattern and factor loadings from the factor analysis of the 33 items. Total variance for each factor could not be reported, as the promax rotation allows for variance to be shared among factors; thus, shared variance will be reported.

Table 3.

Factor Loadings From the Exploratory Factor Analysis

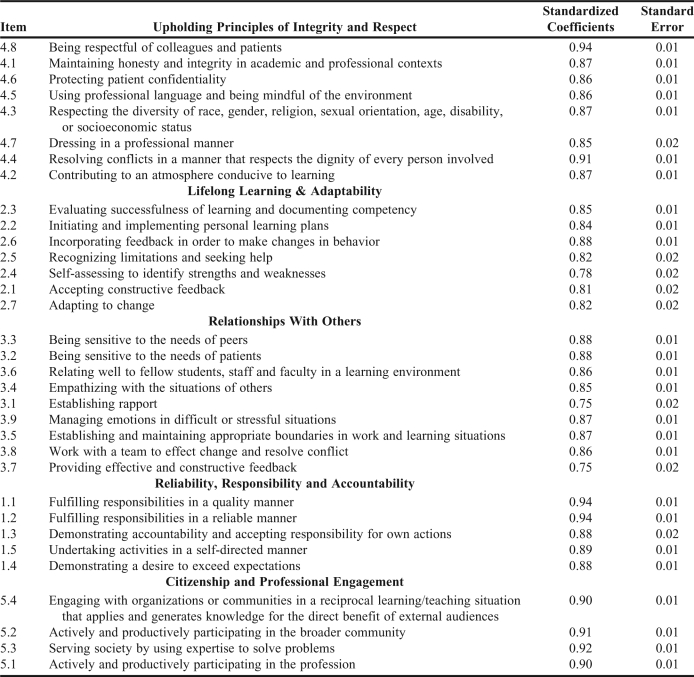

In the first portion of analysis, EFA was used to identify the total number of factors in the data and examine the relationships between variables and factors. The EFA also was used to identify items that did not load on a particular domain or loaded on more than 1 domain. From the EFA, a model with 5 domains and 33 items was fit to the second set of data. The CFA models were constructed using Mplus software (version 6.1, Muthén & Muthén Los Angeles) and results suggest an acceptable model-data fit. Based on these rules suggested by Kline,26 both the RMSEA and SRMR values suggest a good fit of the data to the model (RMSEA = 0.06), confirming the structure suggested by the EFA. Coefficients and the standardized factor structure are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Standardized Coefficients and Standard Errors for a 5-Factor Confirmatory Factor Analysis

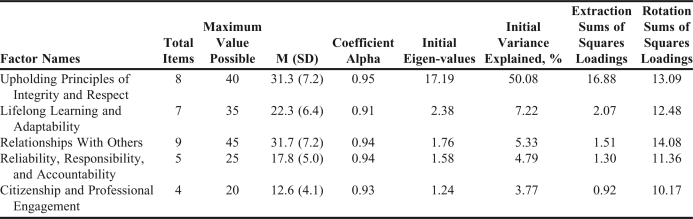

Table 5 displays the descriptive statistics and results of the EFA for each of the 5 domains. The internal consistency of each domain was calculated using coefficient alpha. Each domain showed high levels of internal consistency. Table 5 also displays mean total raw scores relative to the maximum possible scores as a means of assessing the rating scale's performance relative to the ceiling.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics and Exploratory Factor Analysis Results

Eight items loaded to the domain Upholding Principles of Integrity and Respect, accounting for 13.1% of the total shared variance in student responses. The 2 items that loaded highest to this domain were “Being respectful of colleagues and patients,” and “Maintaining honesty and integrity in academic and professional contexts.” Other items loading to this and other domains are presented in Table 3. The mean total raw score for the domain Upholding Principles of Integrity and Respect was 31.2 ± 7.2 out of a maximum of 40 (8 items for each of 5 categories) with a reliability of 0.95, suggesting an excellent ability for the PAT to reproduce the same value for an individual on this domain. Seven items loaded to the domain Lifelong Learning and Adaptability. A sample of items in this domain include: “Evaluating successfulness of learning and documenting competency,” “Initiating and implementing personal learning plans,” and “Incorporating feedback in order to make changes in behavior.” The Lifelong Learning and Adaptability domain accounted for 12.48% of the total variance. The mean total raw score for persons on this factor was 22.3 ± 6.3 out of a maximum 35. Although slightly lower, as with the previous domain, the reliability using the KR-20 was excellent, with a value of 0.91.

Five items loaded to the domain Relationships with Others accounting for 14.08% of the shared variance. “Being sensitive to the needs of patients,” “Relating well to fellow students, staff and faculty in a learning environment,” and “Empathizing with the situations of others” are examples of items that loaded to this domain. The mean raw score was 31.2 ± 7.2, with a maximum value of 45. With a value of 0.945, the KR-20 measure of reliability showed that this domain had excellent reliability.

The 5 items that loaded to the domain Reliability, Responsibility and Accountability represented 11.4% of the shared variance in student responses. Examples of items loading to this domain included “Fulfilling responsibilities in a reliable manner,” “Demonstrating accountability and accepting responsibility for own actions,” and “Undertaking activities in a self-directed manner.” The mean total raw score for this domain was 17.8 ± 5.0, with a maximum of 25. The KR-20 measure of the factor was excellent, with a reliability of 0.94.

Four items loaded to the domain Citizenship and Professional Engagement, accounting for 10.2% of the shared variance in student responses. “Actively and productively participating in the broader community” and “Serving society by using expertise to solve problems” are examples of items that loaded to this domain. The mean total score was 12.4 ± 4.1, out of 20 possible raw score points. As with all other domains on the PAT, reliability using the KR-20 measure was excellent, with data from the Citizenship and Professional Engagement domain exhibiting a reliability of 0.93.

DISCUSSION

This project sought to expand and improve existing tools for measuring professionalism in pharmacy students. The primary aim of this project was to develop and cross-validate an instrument to measure behavioral professionalism in pharmacy students using a rating scale that minimizes response ceiling effects. While the sensitivity of the PAT to measure change in professionalism over time still needs to be established, the distribution of the responses (Table 5) indicates that the ceiling effects experienced with previous tools6 may be moderated with the PAT.

The PAT was created using 5 domains with 4 to 9 items under each domain. Factor analysis of data from the 7-institution evaluation demonstrated that the items loaded under the domain with which they are associated in the instrument (Table 3), indicating that the items under each domain are a valid fit within their respective domains. Given that the instrument is based on the pharmacy literature as well as pharmacy faculty input, the 5 domains of the PAT appear to cover the major components of professionalism in pharmacy today. The literature, faculty approval, and factor analysis combine to prove that the PAT is a valid instrument for evaluating student professionalism.

One hundred fifty-five cases were removed from the analysis because of incomplete data, survey instrument drop off, or completion of the survey instrument with one uniform answer and agreement between strongest and weakest domains. This number of unusable cases may indicate problems with the survey administration, including length of the survey instrument or students’ ability to comprehend, reflect, or respond to items. However, the PAT was administered to students as part of a larger research project including an assessment of student engagement, resulting in a large number of test items to be completed at 1 sitting. Another potential problem was that the instrument was administered near the end of the school year, making it more likely that final examinations and projects took precedence, decreasing the effort and thought that students might otherwise have dedicated to completing the PAT.

All data were collected from students who attended large public colleges or schools of pharmacy. Doctor of pharmacy programs in smaller or private colleges or schools of pharmacy may have different missions, curricula, or teaching styles that address and cultivate professionalism among pharmacy students. These different emphases might suggest the need for an expansion, contraction, or reorganization of items under each professionalism domain in the PAT.

Although results of this study suggest that the PAT has the potential to measure growth over time, establishing its usefulness for this purpose will require additional data collected longitudinally. The use of the PAT with external evaluators, such as laboratory coordinators or preceptors, would be useful in further validating this tool and will be necessary to determine if the instrument can be used for both external evaluation and student self-assessment. Regardless of differences in mission or scope, pharmacy colleges and schools may be able to gauge levels and areas of professionalism development among its students by using the PAT to examine results among cohorts of students (ie, first- vs. third-year students). Both faculty members and administrators also may be able to use the results to assist with professional curricular delivery and revision for pharmacy students.

CONCLUSION

As an instrument for self-assessing the behavioral aspects of professionalism in doctor of pharmacy students, the PAT displays compelling evidence for internal and construct validity. The 5 domains (Reliability and Responsibility, Lifelong Learning and Adaptability, Relationships with Others, Upholding Principles of Integrity and Respect, and Citizenship and Professional Engagement) represent the major tenants of professionalism in pharmacy today. The factor analyses from the 7-school pilot study demonstrate that professionalism items are good fits within each of the 5 domains. Furthermore, the collaboration created a rich environment for developing and supporting future work on assessment in pharmacy education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the work of Anne Guerin Flaherty of the University of Kansas, who assisted with data collection for this study. We also acknowledge the input and support of our colleagues in the Committee on Institutional Cooperation Pharmacy Assessment Collaborative as well as faculty members at our respective institutions who helped craft and refine this instrument.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Inc. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed on September 17, 2011.

- 2.Hammer DP, Mason HL, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Hatala R, McNaughton N, Frohna A, Hodges B, Lingard L, Stern D. Context, conflict, and resolution: a new conceptual framework for evaluation professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(10 Suppl):S6–S11. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. 2nd ed. Oxford England: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beatty SJ, Kelley KA, Metzger AH, Bellebaum KL, McAuley JW. Team-based learning in therapeutics workshop sessions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6):Article 100. doi: 10.5688/aj7306100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutter PM, Duncan G. Can professionalism be measured?: evidence from the pharmacy literature. Pharm Pract. 2010;8(1):18–28. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):Article 85. doi: 10.5688/aj700485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerkiatbundit S. Professionalism in Thai pharmacy students. J Soc Admin Pharm. 2000;17:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerkiatbundit S. Factor Structure and cross-validation of a professionalism scale in pharmacy students. J Pharm Teach. 2005;12(2):25–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schack DW, Hepler CD. Modification of Hall's professionalism scale for use with pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 1979;43(2):98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch DC, Surdyk PM, Eiser AR. Assessing professionalism: a review of the literature. Med Teach. 2004;26(4):366–373. doi: 10.1080/01421590410001696434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veloski JJ, Fields SK, Boex JR, Blank LL. Measuring professionalism: a review of the studies with instruments reported in the literature between 1982 and 2002. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):366–370. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold EL, Blank LL, Race KE, Cipparrone N. Can professionalism be measured? The development of a scale for use in the medical environment. Acad Med. 1998;73(10):1119–1121. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199810000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Haes JC, Oort F, Oosterveld P, Cate OT. Assessment of medical students’ communicative behavior and attitudes; estimating the reliability of the use of the Amsterdam attitudes and communication scale through generalisability coefficients. Pat Educ Couns. 2001;45(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadakis MA, Loeser H, Healy K. Early detection and evaluation of professionalism deficiencies in medical students: One school's approach. Acad Med. 2001;76(11):1100–1106. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy/American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40(1):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203–1207. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63–S67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cudeck R, Browne M. Cross-validation of covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Res. 1983;18(2):147–167. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1802_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss D. Multivariate procedures. In: Dunnette MD, editor. Handbook of Industrial/Organizational Psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comrey AL, Lee HB. A First Course in Factor Analysis. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.George D, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2003. 11.0 update. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: coventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]