Abstract

Objective. To describe the perceptions of student pharmacists, graduate students, and pharmacy residents regarding social situations involving students or residents and faculty members at public and private universities.

Methods. Focus groups of student pharmacists, graduate students, and pharmacy residents were formed at 2 pharmacy schools. Given 3 scenarios, participants indicated if they thought any boundaries had been violated and why. Responses were grouped into similar categories and frequencies were determined.

Results. Compared with private university students or pharmacy residents, student pharmacists at a public university were more likely to think “friending” on Facebook violated a boundary. No participants considered reasonable consumption of alcohol in social settings a violation. “Tagging” faculty members in photos on Facebook was thought to be less problematic, but most participants stated they would be conscious of what they were posting.

Conclusions. The social interactions between faculty members and students or residents, especially student pharmacists, should be kept professional. Students indicated that social networking may pose threats to maintaining professional boundaries.

Keywords: faculty-student relationships, social networking, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

As student pharmacists, graduate students, and pharmacy residents progress through their education, they develop relationships with faculty members through coursework, projects, organizations, and mentoring. Mentors are able to encourage career aspirations, create networking opportunities, increase self-confidence, and socialize mentees into the profession.1,2 Mentoring is also a vital component in the development of professionalism,2-4 and professional students reported that mentoring was important to them. In developing these relationships, faculty members can participate in formal programs that involve students and residents as well as interact informally with them outside the academic setting.5

Student pharmacists, pharmacy residents, and graduate students have opportunities to interact with faculty members through several portals of communication, including online messaging and social networking, as well as events such as professional meetings and conferences. As one of the largest social networking sites, Facebook provides an online domain where faculty members and students can publicly interact. Faculty members can use Facebook as a way to connect with their students for the purpose of matching names to faces or finding topics for course projects,6 but not all faculty members and students are in favor of connecting with each other through Facebook. One study reported that some undergraduate students were concerned about their privacy, the presence of faculty members on the Web site, and overall interaction with faculty members on Facebook.7 These concerns also relate to the terms under which they are “friends,” and how the public content of students’ online profiles reflect on their character or e-professionalism.8-10

As students and residents create these social and professional relationships, referred to as “dual-relationships,” with faculty members, certain boundaries are established that dictate the roles of each member outside the primary faculty-student/resident relationship.11 However, in these social situations, faculty-student/resident boundaries may become unclear. One study analyzed undergraduate student perceptions regarding “boundary crossings” in situations in which faculty members are operating outside their academic roles. Using a Likert scale to rank the appropriateness of various scenarios, students interpreted most of the interactions as inappropriate. Many of these involved financial exchanges, such as borrowing money or receiving expensive gifts from a professor. Several of the scenarios involved alcohol consumption with faculty members. Undergraduate students viewed “a professor accepting a student invitation to a non–school-related party” and “a professor going out for drinks with a student” as inappropriate.11 Although this study analyzed the level of appropriateness of social situations among faculty members and students, the rationale for students’ attitudes was not investigated. Understanding student/resident perceptions of these situations will provide information essential to a discussion of these boundaries.

In previous work examining faculty member perceptions of faculty-student boundaries, most faculty members did not consider it appropriate for faculty members to friend student pharmacists on Facebook. About half of the participating faculty members thought it was a violation of a faculty-student boundary to go to a bar with students after a professional reception. Faculty members felt strongly that they should not purchase drinks for student pharmacists.12 Whether student opinions differ is not known.

Research is needed to investigate boundaries between pharmacy faculty members and residents/students, especially professional and graduate students, to direct policies regarding these relationships at pharmacy colleges and schools. This study did not determine how these social situations might be used explicitly for socialization or mentoring. The objective of this study was to describe the attitudes of student pharmacists, graduate students, and pharmacy residents regarding behavior in social situations involving interactions between students or residents and faculty members.

METHODS

The study was conducted at 2 colleges/schools of pharmacy, including a public and a private university (the University of Iowa and Shenandoah University, respectively). At the University of Iowa, 4 focus groups (n = 19) were conducted: 2 with student pharmacists, 1 with graduate students (n = 3), and 1 with pharmacy residents (n = 4). At Shenandoah University, 2 focus groups (n = 16) were conducted with student pharmacists. Focus groups were used to capitalize on student interactions within a group, based on the expectation that any disagreement and discussion that occurred might inform and affect the perspectives of participants. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Iowa, Shenandoah University, and the University of Michigan approved the study.

Student pharmacists and graduate students enrolled at the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy and pharmacy residents from University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics or the University of Iowa Community Pharmacy Residency Program were eligible to participate in the focus groups. At Shenandoah University, student pharmacists enrolled at the Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy were eligible. Volunteers were recruited from the student pharmacist population by means of flyers posted at the institutions or read to students and residents prior to lectures (University of Iowa) and e-mail solicitation from one of the study investigators (Shenandoah University). At the University of Iowa, graduate students and pharmacy residents were recruited through e-mail communication from the investigators. Interested individuals were asked to contact the investigators by e-mail or in person. Individuals were sent an e-mail reminder prior to the focus group with details about its location. In exchange for their participation, all subjects were provided either lunch or dinner (both universities) and a $5 gift card to a local coffee house (University of Iowa).

Prior to the discussion, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire that included questions regarding age, gender, educational status (student, graduate student, or resident), membership in student organizations, employment at a pharmacy, use of social networking sites, and current work with a faculty member, including compensated research, research for academic credit, or research required by your designated program. Responses to the survey could not be linked to comments in the focus groups. The focus groups were facilitated, audio-recorded, and transcribed by student pharmacist investigators. A question guide containing 3 scenarios was created for the focus groups. Two of the scenarios were based on previous work by the investigators, and an additional scenario about “tagging” pictures in social media was created.12

The first scenario involved a faculty member friending a student or resident (depending on the members of the focus group), on Facebook and then talking to the student or resident about his or her personal relationships. The second scenario involved faculty members and students or residents at a national conference going to a bar for drinks after a reception and concurrently engaging in conversation regarding academic or practice experience performance and the behavior of other students or residents. The third scenario involved students posting pictures on social networking sites and tagging faculty members in these photos. Participants were asked whether the faculty-student/resident boundary had been violated in the 3 different social situations. Given follow-up questions that slightly altered the scenarios, participants were asked again whether the situation was a violation.

For the 3 scenarios, 14 different situations were investigated: 7 situations for friending, 6 situations for drinking at a bar during national meetings, and 1 situation for tagging pictures on social media. These scenarios were selected because friending and tagging in social media are commonplace among many of our student pharmacists and faculty members, and the bar scenario is a common experience of faculty members attending national professional meetings. Graduate students and pharmacy residents were asked about their previous perceptions and whether their current responses were different than they would have been when they were student pharmacists. Participants were asked to indicate why they felt each scenario was or was not a violation, and at the end of the discussion, they were asked about their awareness of formal policies addressing social situations between faculty members and students and residents.

The percentage of participants who considered each situation a violation of the faculty-student or faculty-resident boundary was determined for each of the 14 situations. Any boundary that participants felt had been crossed under any circumstances within a particular scenario constituted a violation. Reasons for the response to each scenario were compiled and grouped into categories of similar content by means of content analysis so that reasons of a similar nature could be grouped into larger themes or categories. The frequencies of these categories and the demographic characteristics of participants were determined. Demographic information was not linked to participant comments during focus groups.

RESULTS

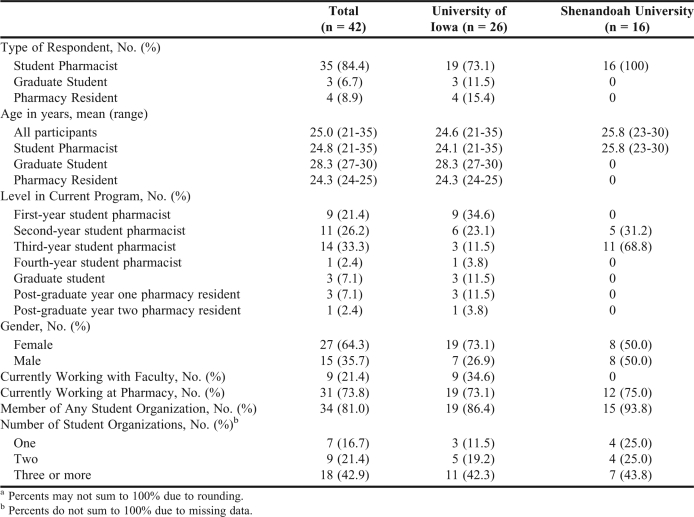

The majority of participants were student pharmacists and two-thirds were female (Table 1). Overall, 89.5% of respondents were members of at least 1 student organization and almost half were involved with 3 or more organizations. Most respondents (78.6%) were not currently working with faculty members but were employed at a pharmacy. Comparing the 2 study institutions, Shenandoah University evaluated only student pharmacists, 68.8% of whom were in their third year, while at the University of Iowa, the majority of participants were female and one third were first year.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group Participantsa

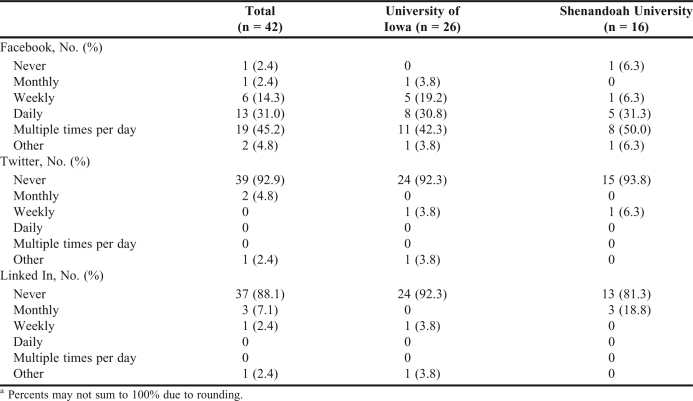

Participants’ use of online social networks was primarily limited to Facebook (Table 2). Most participants reported never having used 2 other social networking services, Twitter and LinkedIn, but almost all had used Facebook. Interestingly, half of student pharmacists reported accessing Facebook multiple times per day compared with 33% of graduate students and 0% of pharmacy residents.

Table 2.

Frequency of Use of Social Networking Sites Among Student Pharmacists, Graduate Students, and Pharmacy Residentsa

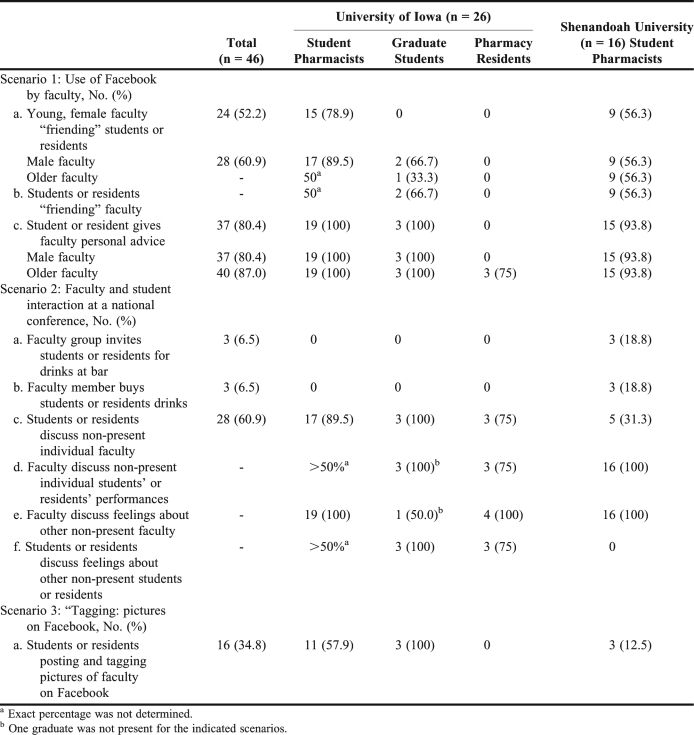

Participants’ opinions of boundary violations between faculty members and students and residents for the 3 different scenarios are summarized in Table 3. In the first scenario, participants were divided regarding whether a friend request from a faculty member would be a violation; however, more student pharmacists at the University of Iowa (78.9%) felt that a friend request from a faculty member would be a violation than did those at Shenandoah University (56.3%). When the faculty member in the scenario was older, fewer student pharmacists at the University of Iowa saw the friend request as a violation in a student-faculty boundary. When the faculty member was male, student pharmacists at the University of Iowa thought the situation was more likely to be a boundary violation. In general, graduate student responses were similar to those of student pharmacists, with the exception of graduate students’ acceptance of Facebook friending by a young, female faculty member. About half of all groups felt that a boundary had been violated if a student friended a faculty member, and the majority of all participants felt that a student pharmacist offering personal advice to a faculty member violated a boundary. Pharmacy residents did not think a boundary was violated except when the communication involved giving advice to an older faculty member through Facebook.

Table 3.

Student Pharmacists, Graduate Students, and Pharmacy Residents Opinions Regarding Whether Certain Social Media Scenarios Are a Violation of Professional Boundaries

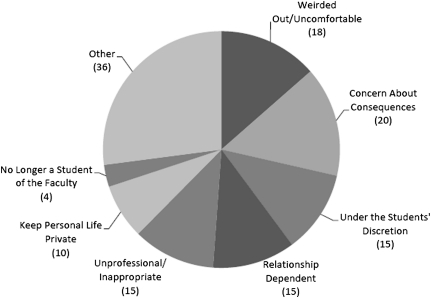

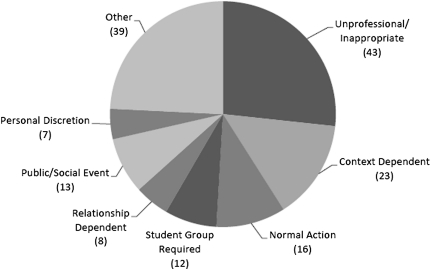

In each of the scenarios, participants were asked to indicate why they thought a violation of faculty-student/resident boundaries had or had not occurred, and these responses were grouped into common themes (Figures 1, 2, and 3). In the first scenario, the most frequent responses fell into the categories of “weirded out/uncomfortable” and “concern about consequences” (Figure 1). The majority of responses in the category of “weirded out/uncomfortable” pertained to the second part of the scenario involving personal advice. Responses related to the “concern about consequences” were based on concerns about faculty member perceptions, perceived preferential treatment, ulterior motives, and obligations to accept a friend request. A category for “student discretion” was created based on responses about students’ or residents’ Facebook profiles and activities, which included limiting profile viewing to specific individuals, whether to accept the friend request, and posting “general” comments about students’ personal lives without specific and perhaps controversial detail. The “relationship dependent” category included responses concerning the type of relationship a faculty member had with his or her students. A few students felt that the act of being friends on Facebook was not in itself a violation of any boundaries unless the relationship became inappropriate. Responses categorized as “unprofessional/inappropriate” also mainly pertained to the second part of the scenario about personal advice, as some students felt that giving personal advice to faculty members on Facebook was unprofessional or inappropriate.

Figure 1.

Reasons for Responses in the Faculty “Friending” Scenario (response frequency).

Figure 2.

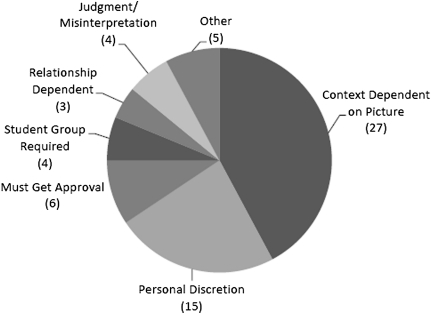

Reasons for Responses in the Bar Scenario (response frequency).

Figure 3.

Reasons for Responses in the “Tagging Pictures” Scenario (response frequency).

In the second scenario, few participants thought that going to a bar and having a faculty member buy them alcoholic beverages violated the faculty-student/resident boundary. However, as the scenario progressed and involved conversation, the majority of participants at the University of Iowa thought that any discussion about students, residents, or faculty members who were not present was a violation. Conversely, Shenandoah University student pharmacists did not consider student discussions of other students and faculty members a violation of boundaries; however, all participants agreed that faculty member discussions about students and other faculty members were violations. Graduate students were less concerned than student pharmacists about faculty members discussing other faculty members.

In this scenario, participants noted that the bar was a similar setting to that of a reception and that if no one was intoxicated or out of control, it was acceptable behavior. The majority of the participants’ responses were focused on the violation of faculty members and student and resident discussions in a social setting. Fewer comments addressed alcohol consumption. The 3 most common themes regarding behavior within the scenario included “unprofessional/inappropriate,” “context-dependent,” and “normal action” (Figure 2). Most responses focused on the unprofessional or inappropriate nature of gossiping, “bashing,” or “ragging on” others. Participants also commented on the setting, saying that a bar is not an appropriate place for this type of discussion. Another category, “normal action” or socially acceptable activity, was based on comments that even though gossiping or talking about others was wrong it was commonplace and provided something to talk about. Responses of the participants who considered the context of the scenario were put into the “context-dependent” category. For example, some participants felt that socializing at a bar was not in itself a violation of any boundaries, as long as everyone used professional judgment. Other participants felt that discussing other students or faculty members was appropriate as long as positive remarks, constructive criticisms, or in some cases, help was offered.

The third scenario was related to students posting pictures and tagging faculty members on Facebook. Student pharmacists and graduate students at the University of Iowa thought that tagging faculty members violated the boundary (53.8%) while pharmacy residents did not (0%). The majority of participants at Shenandoah University (87.5%) did not consider this act in itself a violation. In this scenario, the majority of comments regarding pictures and tagging on Facebook were categorized as “context dependent on picture” and “personal discretion” (Figure 3). Several participants did not think tagging was a boundary violation, as long as the context of the photos was related to school or in honor of a faculty member, did not involve alcohol, and did not include intoxicated people. However, other responses were based on the students’ discretion regarding whether to post pictures at all.

Both graduate students and pharmacy residents were asked if their opinions for each scenario would be different if they were student pharmacists instead. Graduate students and pharmacy residents most often reported that their relationships are different now compared to when they were student pharmacists. The general scenarios were less likely to be considered a violation for graduate students, but the more specified circumstances, such as giving advice to faculty members or discussing other students or faculty members with students, was perceived as more problematic to graduate students than to student pharmacists (Table 3).

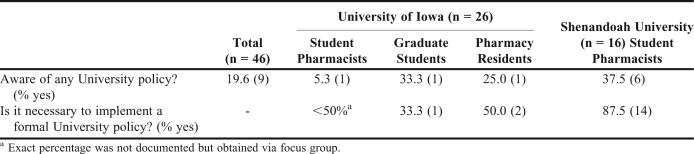

Neither institution had formal policies specifically addressing boundaries in social situations at the time of this study. Students at the private institution were more likely to think that university policy regarding social situations between faculty and students/residents was necessary (Table 4). Less than 20% of participants were aware of any type of university policy related to this topic.

Table 4.

Student Pharmacists, Graduate Students, and Pharmacy Residents’ Views of University Policy Regarding Social Situations

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the perspectives of student pharmacists, graduate students, and pharmacy residents regarding violations of faculty-student boundaries in social interactions involving online networking and alcohol-related settings. Professional students viewed the alcohol-related scenarios differently than did undergraduates, and there were mixed findings about friending faculty members on social networking sites.

In the Facebook-related situations, student pharmacists viewed contact between faculty members and students as a boundary violation. Previous research supports that the majority of students do not want to be “friends” with faculty members on social networking sites.7,9 We found that student pharmacists at a public institution were uncomfortable with faculty “friends” because they questioned the faculty members’ considering their position of authority. Student pharmacists also reported that discussing details of a faculty member's relationships through social media was extremely awkward and were concerned with the content of their own Facebook profiles.8,9 Allowing faculty members to access personal information could lead to a misconception of the students’ character and professionalism and potentially impact their future careers. Therefore, students at a public university felt that interacting on Facebook makes it difficult to maintain a professional relationship with faculty members, whereas some student pharmacists at a private university viewed the scenario differently. Students at the private, smaller university remarked that a faculty member friending a student is just another way to communicate. Cain and colleagues also found that while the majority of student pharmacists did not want faculty members to friend them, students in a private school setting were significantly more likely to want a faculty member as a Facebook friend. The difference in student perception may be attributed to the institutions and student philosophies that led to choosing a private rather than public institution. Students choosing a private institution may be searching for more personal and individual relationships with faculty members. It appears that the use of social media during professional school has varying applications in mentoring and professionalization, depending on the culture of the school. One solution for the problems associated with using social media is to have personal and professional pages or to use privacy settings to limit what can be viewed. It will be important to follow the views of student pharmacists and faculty members over time regarding social media in such applications.

Contrary to the opinions of student pharmacists and graduate students, pharmacy residents did not consider interaction on Facebook a violation of the faculty-resident boundary. Pharmacy residents likely perceived themselves as peers of faculty members. This perception may be attributable to pharmacy residents having the same degree and practice license as faculty members and working with them collaboratively and collegially. As student pharmacists, residents also may have established relationships with faculty members during their residency rotations if they continued to work at the same institution.

Few participants considered alcohol in the social setting a violation of the faculty-student/resident boundary, possibly because most students and residents are of legal age to consume alcohol and drink responsibly. To maintain a professional demeanor, students and residents may limit their alcohol consumption in the presence of faculty members in social settings, and they may perceive having drinks with faculty members as a normal activity considering that alcohol is often present at professional social gatherings. Participants from all focus groups commented that they would not agree with faculty members singling out students and buying them alcoholic beverages. Student, resident, or faculty member intoxication in these situations also was viewed as unprofessional and inappropriate. In comparison, undergraduate students viewed all alcohol-related situations with faculty members as inappropriate, an opinion that may be attributable to previous research focusing on the issues of legal age and attending bars together.11 As reported in the literature, professional students and residents appear to view alcohol-related social situations differently than do undergraduates, provided that there are no conversations specifically about faculty members or student behavior and/or performance.

Participants at a public university were more likely to consider that a boundary violation had occurred if conversations in alcohol-related settings were focused on the behavior of faculty members, residents, or students. This finding may relate to students’ understanding of privacy policies regarding their student records as well as their own insights about professionalism and interactions with colleagues. Student pharmacists at a private university, however, did not see this type of discussion as a violation as long as faculty members did not participate, based on their opinion that faculty members ought to be held to a higher standard than students. Most participants considered this type of discussion as gossip, whereas others saw the situation as an opportunity for positive feedback or just a “social discussion in a social setting.” Overall, participants believed that in a bar or reception situation, discussion of personal information regarding academic-related performance and behavior should be limited to constructive comments or avoided completely.

Responses to the third scenario regarding tagging faculty members in photographs posted on Facebook also varied depending on the institution. Participants at the public university were more likely to consider it a violation. They stated that they would not post anything that would lead to undesired consequences and would use their best judgment when posting photos on Facebook based on their relationship with the faculty member and the content of the pictures. The variation in these responses could be attributable to the fact that photos are often taken during social events at professional meetings and that faculty members are unlikely to be in a social setting with students unless it is a professionally related situation. Some participants may assume that a professional setting would justify why students would tag faculty members. However, some participants noted that students should ask faculty members for permission to tag them prior to posting photos.

Despite finding fewer violations in faculty-student boundaries in the scenarios, students at the private institution were more likely to feel that a formal policy addressing social boundaries was needed. Participants felt that a written policy would help make social boundaries “black and white” and eliminate any confusion about what was and was not appropriate. Participants at the public university, however, were reluctant to support a formal university policy addressing social boundaries. They did not think meticulous policies outlining the use of online social networks were necessary, and that if a situation arose, students would know how to manage it.

This was a focus group study conducted at 2 colleges or schools of pharmacy. Because some focus groups were small, the results are not generalizable to all student pharmacists, pharmacy residents, or graduate students. However, because the student pharmacist participants were primarily female and many were working in a pharmacy, these results are likely representative of student pharmacists. The fact that 1 private and 1 public university were involved in the study is a strength. Although more second- and third-year students participated, it is unlikely that they would have opinions so different from the remainder of student pharmacists. Reasons for the responses were coded by one investigator (JB) and reviewed by a second (KF), and those same codes/categories were used by the second investigator (CV). The quantitative survey tools were not linked to the focus group discussions, and the qualitative data were not examined by demographics. The ideas and concepts from these focus groups will be translated into a quantitative survey tool that may be used in future studies. This was a descriptive study that, combined with previous research, may be useful in considering how social interactions impact mentoring and professional socialization of student pharmacists, residents, and graduate students into and about the profession as well as the academy.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the social interactions between faculty members and students or residents, especially student pharmacists, should be kept professional. Most students were reluctant to engage with faculty members on Facebook because of the ethos of social networks; however, students at a private, smaller university appeared more accepting of faculty-student relationships in social media. Pharmacy residents were unconcerned about this situation. All students and residents were comfortable with faculty members in professionally oriented social settings involving alcohol, such as at a bar or reception, provided everyone was responsible about their alcohol consumption. By studying the relationships between faculty members and students/residents, relevant data can be used to improve mentoring programs and to contribute to the professional socialization of student pharmacists, residents, and graduate students.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wright CA, Wright SD. The role of mentors in the career development of young. Fam Relations. 1987;36(2):204–208. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macaulay W, Mellman LA, Quest DO, Nichols GL, Haddad J, Jr, Puchner PJ. The advisory dean program: a personalized approach to academic and career advising for medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(7):718–722. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180674af2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paglis LL, Green SG, Bauer TN. Does adviser mentoring add value? A longitudinal study of mentoring and doctoral student outcomes. Res High Educ. 2006;47(4):451–474. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose GL, Rukstalis MR, Schuckit MA. Informal mentoring between faculty and medical students. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):344–348. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.College of Information Studies. University of Maryland. Facebook: changing the way faculty and students interact. http://ischool.umd.edu/content/facebook-changing-way-faculty-and-students-interact. Accessed October 24, 2011.

- 7.Hewitt A, Forte A. Crossing boundaries: identity management and student/faculty relationships on the Facebook. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) Conference. Banff, Alberta, Canada. November 4-8, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynesworth L. Faculty with Facebook wary of friending students. The Daily Princetonian. 2009. http://www.dailyprincetonian.com/2009/02/18/22793. Accessed September 18, 2011.

- 9.Cain J, Scott DR, Akers P. Pharmacy students’ Facebook activity and opinions regarding accountability and e-professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6):Article 104. doi: 10.5688/aj7306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cain J. Online social networking issues within academia and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1):Article 10. doi: 10.5688/aj720110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owen PR, Zwahr-Castro J. Boundary issues in academia: student perceptions of faculty-student boundary crossings. Ethics Behav. 2007;17(2):117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider EJ, Jones MC, Farris KB, Havrda D, Jackson III KC, Hamrick TS. Faculty perceptions of appropriate faculty behaviors in social interactions with student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 70. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]