Abstract

Objectives

Women with diabetes have elevated gestational risks for severe hemodynamic complications, including preeclampsia in mid- to late pregnancy. This study employed continuous, chronic radiotelemetry to compare the hemodynamic patterns in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice who were overtly diabetic or normoglycemic throughout gestation. We hypothesized that overtly diabetic, pregnant NOD mice would develop gestational hypertension and provide understanding of mechanisms in progression of this pathology.

Study Design

Telemeter-implanted, age-matched NOD females with and without diabetes were assessed for six hemodynamic parameters (mean, systolic, diastolic, pulse pressures, heart rate and activity) prior to mating, over pregnancy and over a 72 hr post-partum interval. Urinalysis, serum biochemistry and renal histopathology were also conducted.

Results

Pregnant, normoglycemic NOD mice had a hemodynamic profile similar to other inbred strains, despite insulitis. This pattern was characterized by an interval of pre-implantation stability, post implantation decline in arterial pressure to mid gestation, and then a rebound to pre-pregnancy baseline during later gestation. Overtly diabetic NOD mice had a blood pressure profile that was normal until mid-gestation then become mildly hypotensive (−7mmHg, P<0.05), severely bradycardic (−80bpm, P<0.01) and showed signs of acute kidney injury. Pups born to diabetic dams were viable but growth restricted, despite their mothers’ failing health, which did not rebound post-partum (−10% pre-pregnancy pressure and HR, P<0.05).

Conclusions

Pregnancy accelerates circulatory and renal pathologies in overtly diabetic NOD mice and is characterized by depressed arterial pressure from mid-gestation and birth of growth 45 restricted offspring.

Keywords: Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Pregnancy, Radiotelemetry, Hemodynamics

Cardiovascular complications are common and progressive in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), often leading to significant morbidity and death. Pregnancy has been described as a physiological stressor and early predictor of cardiovascular disease when outcomes are abnormal [1]. Women with pre-existing diabetes (autoimmune and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus) are considered high-risk obstetrical patients with significantly increased risks for complications; including worsening of pre-existing diabetic sequelae (diabetic nephropathy, retinopathy and altered glycemic control), pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia and thromboembolic events [2–5]. Severity of the pre-existing diabetic disease status rather than glycemic control is used to stratify risk for these women. Risks for the fetuses and children of mothers with diabetes include congenital defects, growth restriction due to placental insufficiency, pre-term birth, macrosomia and elevated risk for adult development of non-insulin dependent diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [3,5,6].

Normal mammalian gestation is characterized by progressive gains in blood volume and extracellular fluid, which must be appropriately handled by the maternal cardiovascular system. Such physiological adaptations during gestation include concentric (reversible) cardiac hypertrophy, increased cardiac output, increased heart rate and decreased blood pressure and decreased peripheral vascular resistance [7–10]. Changes in the uterine vascular bed include significant expansion of the capacity of the uterine arteries, veins and downstream vessels. In women, mice and the other species with hemochorial placentation, spiral arteries (SA), branch from the radial arteries (fed from uterine arteries), expand via angiogenesis and structural remodeling into the decidualizing uterus to supply the fetal placenta. By mid-pregnancy, SA typically complete their transient remodeling, a process mediated, at least in part, by molecules produced by uterine (u)NK cells and trophoblast cells. SA remodeling is thought to transform this arterial tree to a high capacity, low resistance conduit that is unresponsive to vasoactive substances and thus provides continuous placental perfusion. In human pregnancies complicated by diabetes, placental insufficiency is seen more frequently, implicating inadequate remodeling of SA [11,12].

The NOD mouse is a well-established model of autoimmune T1DM that shares several diabetes-susceptibility genes with humans. NOD mice spontaneously develop overt diabetes after 12 weeks of age. Insulitis is evident in all NOD mice at 4 weeks of age, whether or not hyperglycemic (blood glucose >15mmol/L on two consecutive samples) conversion occurs. Diabetes in NOD mice has an extremely high female predilection, affecting 80–90% of females by 30 weeks of age vs. 50–60% of males. Despite this, little is known about reproduction in diabetic NOD mice and if its study would provide mechanistic information valuable in understanding the pathologies commonly associated with human diabetic gestations. Thus, we extend our examination of the pregnant non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse. We previously reported the mid-gestational features in implantation sites of overtly diabetic NOD dams [13]. Comparisons between diabetic, normoglycemic NOD and diabetes-resistant congenic T and B cell deficient NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid (NOD.scid) mice during pregnancy, revealed that diabetic NOD mice had significantly impaired spiral artery remodeling and a numerical deficit in uNK cells. Diabetes-induced placental insufficiency was postulated because gestation day (gd)18 fetuses were growth restricted. We additionally showed that only diabetic NOD dams displayed dysfunctional interactions in vitro between endothelial cells and lymphocytes that are characteristic of human T1DM. A weakness in this model was that glycemic control could not be achieved during pregnancy using insulin treatment. Subcutaneous implantation of slow release insulin rods gave glycemic control until gd6, when all of the females reverted to hyperglycemia (unpublished). Because non-pregnant, overtly diabetic NOD female mice have relatively stable hemodynamic profiles [14], we asked, using chronic continuous radiotelemetry, how pregnancy modifies hemodynamic regulation in these mice. The pattern of normal gestational MAP has been defined in wild type (+/+) C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice [15] and is dynamic. We hypothesized there would be an appearance of hypertension in overtly diabetic NOD females between mid- to late gestation; this would permit subsequent modeling of pharmacologic interventions.

Methods

Mice

NOD/ShiLtJ (NOD) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and maintained on irradiated chow (Purina, Richmond, IN) and autoclaved, acidified water under specific pathogen-free conditions. At 10 wks of age, female NOD mice were surgically implanted with TA11PA-C10 radiotelemeter units (Data Sciences International; DSI, St. Paul, MN). Catheters were placed into the left common carotid artery. Anesthetic, surgical and post-surgical protocols were as previously described [15]. From 12 wks of age, twice weekly blood glucose levels were measured in female and male mice using tail vein samples and One Touch Glucometer and strips (LifeScan, Burnaby, BC). Overt diabetes was defined as blood glucose >15mmol/L on two consecutive measures. Only normoglycemic (blood glucose <9.0mmol/L) males were used as studs, diabetic males were euthanized. Blood glucose measurement was continued biweekly on all study mice. Transmitter-implanted females who developed diabetes (occurring between 12–20 wks of age in this study set) were immediately entered into study with a paired, age-matched normoglycemic NOD female. All animal usage and protocols were approved by Queen’s University Animal Care Committee.

Study Design

A continuous, 3-day baseline recording was obtained from the paired females upon study entry. These pre-mating data provided the normal hemodynamic baseline and were compared against early (gd0-3) pregnancy measures of MAP. In normal mice, gd0-3 MAP does not to differ from pre-pregnancy baselines permitting comparisons against the multiday mean of all of these points [15]. Data were acquired using Dataquest A.R.T.™ Acquisition System (DSI, version 4.1) and were collected for MAP, systolic arterial pressure (SAP), diastolic arterial pressure (DAP), heart rate (HR), pulse pressure (PP) and activity. Readings were obtained for 30 sec every four min for each 24-hrs. At 11AM daily, study mice were placed in modified metabolic cages without food or water for spot-urine collection. They were checked for urine output every 30 min for up to 2 hrs then returned to their home cages to continue recording. Feces-free urine samples were collected into sterile Eppendorf tubes using aseptic technique and stored at −80°C until assayed. After the acquisition of baseline data, transmitters were turned off, and females were paired with NOD studs. Visualization of a copulation plug was called gd0. At gd0, males were removed and transmitters were re-activated. Recordings were made throughout gestation, birth and the first three post-partum days with neonates removed the morning of birth, weighed and euthanized. During pregnancy, females were observed daily; blood glucose and body weight measurements were made frequently. Diabetic females were supplemented with moist chow, Napa Nectar™ and s.c. fluids (Lactated Ringer’s Solution, 0.5–1ml) as required. Administration of fluids had no acute effect on hemodynamic measurements (data not shown).

Urinalysis and Serum Biochemistry

Urinary microalbumin and creatinine were assayed using Albuwell M and Creatinine Companion ELISA kits (Exocell Inc., Philadelphia, PA). Frozen samples were thawed and centrifuged to pellet particulate matter. Supernatants were diluted in either EIA diluent or dH2O and assayed according to manufacturers’ directions. Each sample was run in duplicate, using appropriate standards and blanks in each run with a minimum of 4 animals assayed per time point. ELISA plates were read at 450nm (albumin) and 500nm (creatinine). Standard serum biochemistry was conducted at Kingston General Hospital Clinical Laboratory using a Beckman Coulter UniCel® DxC 800 System (Mississauga, ON). Serum phosphate levels were measured using the malachite green method described in [16] except that the ammonium molybdate stock was prepared in dH2O. A 100μM stock solution of K2HPO4 was used for standard curves; 0–50μL was added to wells of a microplate to produce standards of 0–5nmol, respectively. Samples and standards were diluted up to 200μL with dH2O water then 30μL malachite green working reagent was added. Samples and standards were run in duplicate. Absorbance (650nm) was read at 10 min using a microplate reader. R2 values of 0.998 and higher were consistently achieved.

Histopathology

All transmitter-implanted diabetic and normoglycemic and some nontransmitter implanted females were euthanized post-partum by deep anesthesia (Tribromoethanol 250mg/kg) followed by cardiac puncture for large-volume blood collection. Blood was allowed to clot (30 min, room temperature in serum separator tubes; BD, Mississauga, ON), then centrifuged (1200g, 15 min). Serum was transferred to a sterile cryotube and stored at −80°C until assayed. NOD organs were examined grossly for pathology, and then kidneys were dissected, fixed (8h) in fresh, 4% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON) and paraffin-embedded using standard techniques. Sections were cut at 5μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin and observed and photographed using a Zeiss AxioVision photomicroscope.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Prism 4.03 Statistical Software Package (GraphPad, San Diego, CA), and are presented as means ± SEM. Hemodynamic data were analyzed using 24-hr means from individual animals. Baseline, post-partum and gestational hemodynamic data (between groups) were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Within group gestational hemodynamic data were analyzed by paired 1-way repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test. When sample sizes were unequal, Bartlett’s correction was used. Neonatal outcomes and serum biochemistry were compared between groups using unpaired 2-tailed t-tests. Albumin:creatinine ratios were grouped (non-pregnant, gd1-4, gd5-9, gd10-14, gd15-19 and post-partum) and analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Pre-conception and post-partum hemodynamic measurements in overtly diabetic and normoglycemic NOD females

Before mating, the age-matched diabetic and normoglycemic NOD females had similar blood pressures (MAP, SAP and DAP), HR, PP and activity levels, P>0.05 (Table 1). Following term delivery, live pups were removed at 8am and recording was stopped over the following 24hr to permit hemodynamic stabilization. Three days of recording resumed at 8am on postpartum day 2 and were compared to pre-conception baselines to determine if the cardiovascular system had postpartum change. In both groups, post-partum recordings were stable over the 72 hr study interval. Normoglycemic NOD females had no postpartum differences in blood pressure assessments, HR, PP or activity levels compared to their pre-conception values (P>0.05). In contrast, post-partum diabetic NOD mice had consistently lower MAP (P<0.01), SAP (P<0.05) and DAP (~10%, P<0.01), reduced HR (~9%, P<0.01) and reduced activity levels (75%, P<0.01). Despite these changes, diabetic NOD PP remained unaltered during the post-partum interval. The hemodynamic features of four telemeter-implanted NOD mice (mean blood glucose 30.2±1.7mmol/L) that became diabetic but did not become pregnant remained stable (supplementary Figure 1). These four mice were paired with proven studs for ten days but did not become pregnant. Recording was begun after removal of the male to obtain age-matched non-pregnant diabetic NOD recordings. The MAP of these mice (104±0.8mmHg) was intermediate between pre-partum or post-partum diabetic NOD mice and did not statistically differ from either. The HR of non-pregnant diabetic mice (620.1±4.2bpm) was different to both pre-partum and post-partum diabetic mice (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Hemodynamics and blood glucose of normoglycemic and diabetic NOD mice prior to pregnancy (baseline) and post-partum (beginning 24 hours following removal of pups the morning of parturition for three continuous days).

| Normoglycemic NOD | Diabetic NOD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Baseline (n=9) | Post-Partum (n=5) | Baseline (n=5) | Post-Partum (n=5) | |

| MAP (mmHg) | 113.2 (1.3) | 115.1 (0.06) | 107.9 (0.7) | 100.4 (3.3)*# |

| SAP (mmHg) | 121.2 (1.7) | 127.2 (1.2) | 118.5 (1.1) | 111.0 (4.4)# |

| DAP (mmHg) | 99.3 (0.9) | 101.8 (1.4) | 97.0 (0.9) | 88.9 (2.5)*# |

| HR (bpm) | 665.2 (11.5) | 676.7 (7.7) | 647.2 (7.7) | 586.6 (11.0)*# |

| PP | 21.9 (0.9) | 25.4 (2.5) | 21.4 (1.2) | 22.1 (2.3) |

| Activity | 11.3 (2.0) | 9.2 (1.0) | 20.0 (2.1) | 5.3 (0.6)* |

| Blood Glucose (mmol/L) | 6.1 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.4) | 20.0 (1.0)* | >33.31*# |

All post-partum diabetic NOD mice had blood glucose values above limit of detection.

Data (mean arterial pressure, MAP; systolic arterial pressure, SAP; diastolic arterial pressure, DAP; heart rate, HR; pulse pressure, PP, activity and blood glucose) are presented as mean (±SEM).

P<0.05 compared to baseline.

P<0.05 compared to post-partum normoglycemic NOD.

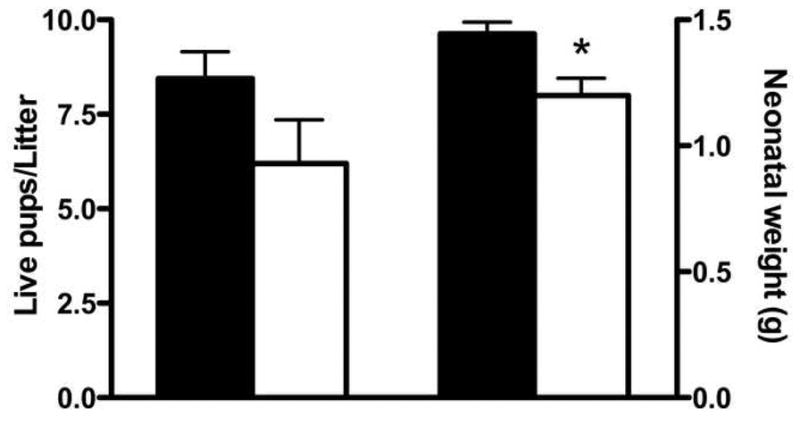

Offspring of diabetic NOD females are growth compromised

Overtly diabetic NOD females are usually removed from breeding programs due to their fragile health and poor reproductive fitness [17]. However, with diligent supplemented husbandry and nursing care (see methods), diabetic dams in this study delivered live pups. Consistent with published data, normoglycemic NOD dams delivered and nursed large healthy litters (8.44 ± 0.71 pups/litter, Figure 1A). These dams had blood glucose values that remained within normal range (between 4.5–9.5mmol/L) throughout gestation, while all diabetic dams had blood glucose values >33.3mmol/L after gd6 (exceeded limit of glucometer detection; data not shown). Five of the seven diabetic dams in this study had live-born offspring who nursed appropriately (6.20 ± 1.16 pups/litter, P=0.10 vs. normoglycemic, Figure 1A). These pups weighed less than pups from normoglycemic dams (1.20g ± 0.21 vs. 1.44g ± 0.17 respectively, P<0.01, Figure 1B). Two diabetic dams delivered small litters (two pups) of stillborn pups with neural tube defects, as others and we have previously reported. These pups were severely growth restricted, weighing less than 0.7g each, likely having died late in gestation due to malformations.

Figure 1.

Neonatal outcomes of normoglycemic and diabetic NOD dams. Average litter size for normoglycemic (n=9, black bar) and diabetic (n=5, white bar) dams. Average weight at birth for normoglycemic (n=76, black bar) and diabetic (n=31, white bar) pups. *P<0.01.

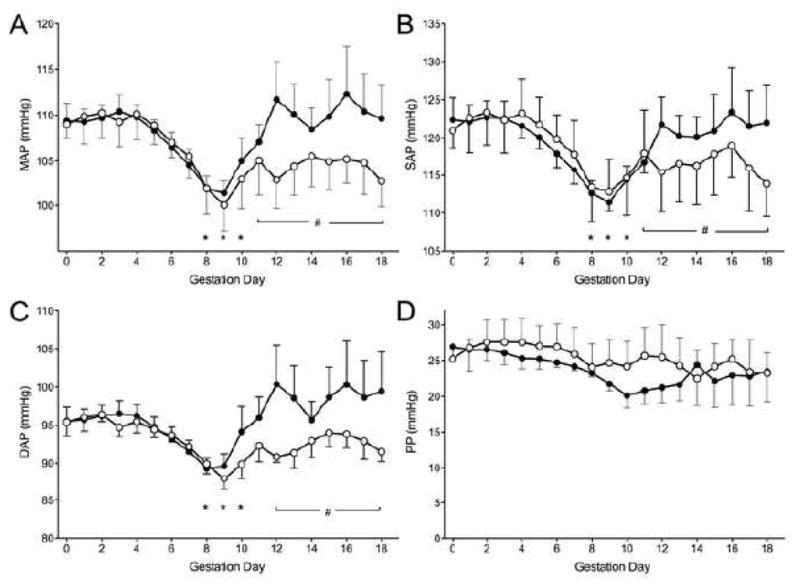

From mid-gestation to parturition, diabetic NOD females have aberrant MAP

The dynamic gestational pattern of MAP previously described for normal mice correlates with key steps in placental development [15]. The MAP of pregnant normoglycemic NOD females matched this pattern. That is, MAP was stable from gd0-5, declined to a nadir at gd9, then rose to gd14 and remained near the pre-conception baseline until term (Figure 2A). The MAP of diabetic dams was identical until gd10. However, from this point, MAP, SAP and DAP, but not PP, of diabetic mice all remained low and were significantly below the pre-conception baseline until term (P<0.05, Figure 2) and at 24–96 hr post partum (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Pressures of normoglycemic (n=6, black circles) and diabetic (n=5, white circles) over gestation. A) Mean arterial pressure (MAP). B) Systolic arterial pressure (SAP). C) Diastolic arterial pressure (DAP). D) Pulse pressure (PP). Data is averaged over a 24-hour period, presented as mean±SEM. *P<0.01 compared to baseline (both groups), #P<0.05 compared to diabetic NOD baseline.

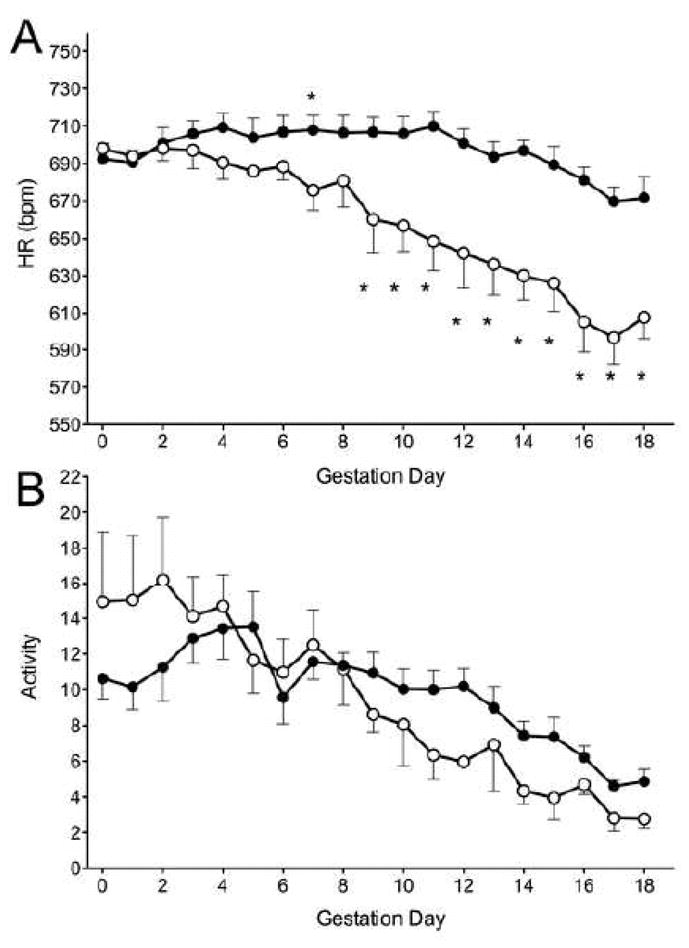

Diabetic NOD mice have progressive gestational bradycardia

Gestational increases in maternal HR have been reported in mice and in humans, an effect that appears to offset the decrease in peripheral vascular resistance [15]. In the present study, normoglycemic NOD mice had HR increases in early gestation that returned to baseline by term (Figure 3A). In contrast, HR in diabetic dams declined sharply from gd9 to term, resulting in severe peri- and post-partum bradycardia (P<0.01, Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

A) Heart rate (HR) and B) activity level of normoglycemic (n=6, black circles) and diabetic (n=5, white circles) over gestation. Data is averaged over a 24-hour period, presented as mean±SEM. *P<0.01 compared to baseline.

HR in normal pregnant mice correlates positively with activity level, which typically rises initially in pregnancy then slowly declines to term. The level of activity in normoglycemic and diabetic mice was similar throughout gestation despite the differences in HR (Figure 3B).

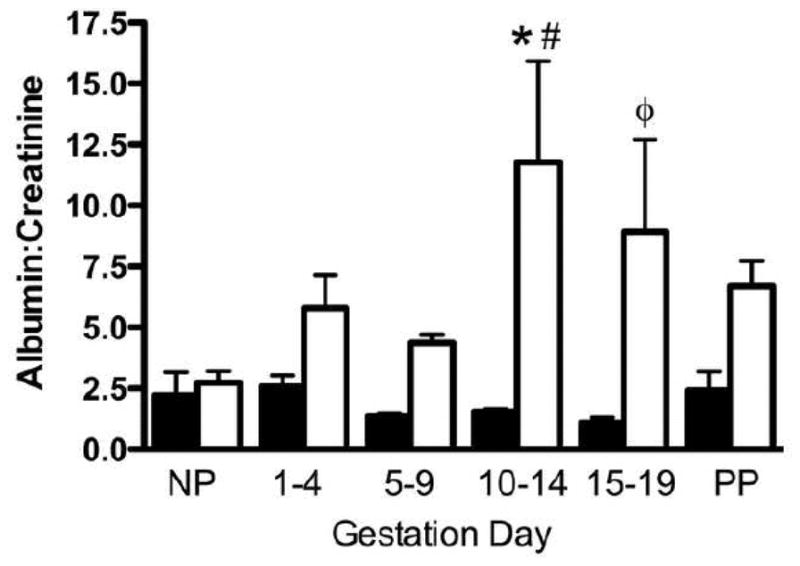

Pregnancy in spontaneously diabetic NOD females promotes renal dysfunction

Because the kidney has significant roles in hemodynamic regulation, renal function was assessed. Due to the association of microalbuminuria and proteinuria with diabetes, this gestational time-course study assessed whether pregnancy impacts significantly on established renal impairment. Normoglycemic NOD dams had no alterations in urine albumin:creatinine ratios. These were within normal limits measured in age-matched non-pregnant mice, throughout gestation and post-partum (Figure 4). Age-controlled, non-pregnant diabetic NOD mice (16 weeks) had a similar albumin:creatinine ratio to normoglycemic NOD mice. However, in pregnant diabetic mice this ratio doubled, at minimum, at gd10-14 and gd15-19 compared to both earlier gestation days and normoglycemic NOD mice at the same gestation day.

Figure 4.

Microalbumin:creatinine from spot urine samples from normoglycemic (black bar) and diabetic (white bar) mice. Time points examined are non-pregnant (NP), gestation day (gd)1-4, gd5-9, gd10-14, gd15-19 and post-partum (PP). N=4–6 animals per time point, with minimum three samples/animal/time point. *P<0.01 vs. normoglycemic NOD mice, #P<0.05 vs. NP diabetic NOD mice. ΦP<0.01 vs. gd15-19 normoglycemic NOD mice.

Serum biochemistry at 96-hr post-partum revealed significant electrolyte imbalances in diabetic NOD mice confirming the presence of metabolic disturbance (Table 2). Sodium and chloride concentrations were decreased, with the sodium imbalance likely mediated by a pseudohyponatremia, consequent to the uncontrolled hyperglycemia. Serum urea and phosphate, markers of renal impairment, were significantly elevated while total serum protein was decreased. Of note, lipemic serum samples were obtained from diabetic dams.

Table 2.

Serum biochemistry of normoglycemic and diabetic mice. Data are presented as mean (±SEM). P values as indicated.

| Electrolyte | Normoglycemic NOD (n=6) | Diabetic NOD (n=7) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 156 (4.6) | 138 (4.8) | 0.0001 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 121 (6.1) | 106 (7.9) | 0.01 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 5.3 (1.2) | 10.4 (3.0) | 0.01 |

| Total Protein (g/L) | 40 (5.2) | 31 (0.6) | 0.04 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.67 (0.24) | 2.08 (0.24) | 0.02 |

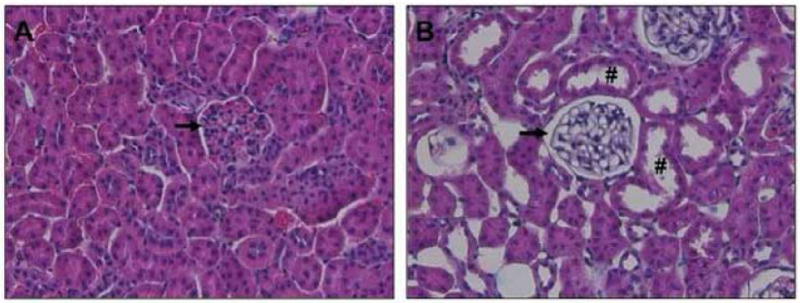

Renal histopathology supported the laboratory findings in diabetic dams. While kidneys from 96 hr post-partum, normoglycemic NOD mice were grossly and histologically normal (Figure 5), those from post-partum diabetic NOD mice were not. In one of seven dams, a gross renal calcification was seen involving the superior pole of one kidney. Histologically, this calcification was attributed to infarction of an interlobular artery and considered a random finding. In another dam, one entire kidney was grossly pale. No histopathologic cause for this could be established. In general, the kidneys from 96 hr postpartum diabetic mice were morphologically normal with respect to typical signs of diabetic nephropathy; however few mild, early pathological processes were identified. Glomeruli tended to be slightly larger than those of the normoglycemic controls and showed mild mesangial and macula densa hypertrophy. Red blood cell and hyaline casts were occasionally observed within tubules. Interestingly, renal histology from 96 hr post-partum diabetic mice revealed signs of acute kidney injury (AKI), such as loss of brush border in the majority of proximal tubules and tubular vacuolization (similar to Armanni-Ebstein lesions in humans). On one hand, such lesions are a known consequence of uncontrolled hyperglycemia in humans [18], but are also widely appreciated as typical signs for murine AKI. Of note, no morphological surrogates of AKI were seen in non-diabetic pregnant control mice (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Renal histology of 96-hr post-partum NOD mice. A) normoglycemic NOD mouse B) Diabetic NOD mouse. Images highlight a representative area of the renal cortex (n=5/condition). H&E staining showed normal histopathology in normoglycemic mice. Diabetic mice did not exhibit typical changes consistent with diabetic nephropathy, in particular no glomerulosclerosis (black arrows). However, kidneys from diabetic mice showed evidence for the presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), such as dilated proximal tubules with loss of brush border (#) and overall moderate vacuolization of tubular epithelial cells.

Discussion

We sought to define the gestational cardiovascular phenotype of diabetic and normoglycemic NOD mice to determine if outcomes in diabetic dams would provide a model to understand progression of complications in human diabetic pregnancies. Study of overtly diabetic NOD mice throughout pregnancy revealed a decompensating cardiovascular phenotype with progressive renal abnormalities. Apparently at the cost of maternal health, live offspring were born but with significant growth restriction. Unexpectedly, no hypertensive features were observed in diabetic dams. The cardiovascular and renal systems were, however clearly impacted by pregnancy confounded by pre-existing diabetes. Of interest, the maladaptive cardiovascular changes characterized by both decreased blood pressure and heart rate persisted post-partum, suggesting that pregnancy may have exacerbated vascular damage. In other studies, return to baseline hemodynamic properties is seen in less than 24 hr from pup delivery [15].

We hypothesized that diabetic NOD mice would exhibit gestational hypertension or preeclamptic signs, similar to human T1DM gestations. Endothelial dysfunctions are thought underlie the increases in human risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Although altered endothelial cell functions are reported in NOD mice, none provide a mechanistic explanation for the hypotensive blood pressure profiles we observed during diabetic pregnancies. Further studies, including cardiac histopathology in non instrumented, post partum diabetic females will be required to explain these observations. Previous hemodynamic studies of non-pregnant diabetic animals have not provided a consensus in cardiovascular phenotype. Indeed, characteristics of published blood pressure profiles depend, in part, on model selection and on the assessment methodology used [19–21]. The majority of available work has utilized streptozotocin (STZ), a β-cell toxin, to induce T1D diabetes in mutant or gene knock-out rodents. STZ-induced models frequently exhibit moderate hypertension, proteinuria and renal damage, aspects that mimic the human T1DM. However, Farah et al., found that STZ-treated AT1RKO mice showed no change in MAP with increasing blood glucose compared to WT mice, which developed hypertension [19]. The rapid-onset of STZ-induced diabetes and clinical disease (7 days, depending on dosing) is however not characteristic of the chronic, progressive human pathology. In the present investigation, spontaneous diabetes in the NOD mouse was selected to most closely represent human disease progression. Gross et al. studied diabetic and normoglycemic NOD mice using radiotelemetry over 19 weeks (beginning at 15–20 weeks); they found age-related declines in MAP and HR in both groups [14]. A significant drop in HR with stable MAP was found following long-standing diabetes (five weeks), which the authors postulated was due to an imbalance in the autonomic nervous system. While Gross et al. studied much older mice, our results concur, finding no acute changes in normoglycemic mice, even with the additional stress of pregnancy. However, in diabetic mice, we not only found relative bradycardia, but also hypotension and signs of AKI. The stability and timing of the hypotension within the group of diabetic pregnant mice suggests resetting of baroreceptors. This may be a response to AKI occurring around mid-gestation, resulting in reset of baroreceptors downward ~10%. The acute hypotension, combined with the early post-partum persistence of the hemodynamic changes, confirms this phenotype is a result of pregnancy with co-morbid diabetes. The increasing proteinuria over gestation in diabetic NOD mice reinforces the pathological nature of these alterations a conclusion further supported by the post-partum electrolyte changes. Proteinuria underlies renal dysfunction; as corroborated in our model by signs of acute renal failure observed on histology. Combined with the cardiovascular phenotype observed, these data indicate a substantial adaptive capacity of the diabetic NOD renal system during pregnancy.

The mechanisms involved in the cardiac decompensation found in this model will be complex and must take into account the transient, but marked structural and functional cardiac and vascular changes that occur during pregnancy. For example, in addition to structural cardiovascular adaptations, pregnancy increases sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity and the renin-angiotensin system RAS. The former is likely to be linked mechanistically to increases in heart rate and vascular tone, while the latter enhancement would primarily promote sodium and water retention. The circulatory system of the pregnant diabetic NOD mouse appeared somewhat refractory to adrenergic and RAS signals. This is supported by studies of overtly diabetic non-pregnant NOD mice that links hyperglycemia with vascular dysfunction [22]. Aortic rings from diabetic NOD mice have significantly impaired nitric oxide (NO)-dependent relaxation and vasoconstriction [22]. With increasing hyperglycemia, the authors found complete absence of contractile response to adrenergic signaling. However, normoglycemic NOD mice retained vascular reactivity similar to normal mice (CD-1) [22]. Normoglycemic NOD mice proceeded through pregnancy without complication, suggesting that in the disease-free state, neural, cardiovascular and endocrine adaptations are intact. In pregnant diabetic NOD mice, bradycardia preceded hypotension, indicating an early change in the trajectory of circulatory adaptations. Impaired capacity for the requisite fluid retention and associated blood volume expansion during critical intervals throughout gestation may be a root cause of the observed bradycardia. In addition, overtly diabetic mice are both polyuric and polydipsic and normal regulatory mechanisms may have been further complicated by damage to the kidneys as revealed by proteinuria. Interestingly, we found a significant elevation of proteinuria during late gestation compared to early gestation and to non-pregnant diabetic mice. This time point was coincident with the major cardiovascular aberrations. Proteinuria, as an indicator of renal function, combined with elevations in serum phosphate and urea suggests the onset of pre-renal failure. This form of injury can be accompanied by systemic microvascular disease, endothelial dysfunction, tissue calcification and vascular leakage, which can significantly deplete blood volume [23–25].

The lack of recovery of MAP in diabetic NOD females from gd10-18, was likely exacerbated by the downward trajectory of the HR profile, and probably reflects the inadequate maintenance of blood volume. Despite these mid to late gestational maladaptations, there were live births. A decrease in blood volume would normally be compensated for by activation of various fluid retention mechanisms including the SNS, RAS and antidiuretic hormone. Given the discordance in the diabetic hemodynamic profile, the magnitude of the neurohormonal activation was insufficient. An acute decline in cardiac function is seen in only a few specific clinical conditions: circulatory shock and cases of nephrotic syndrome with co-morbid disease [26,27]. The former refers to a state of inadequate systemic tissue perfusion and leads to widespread hypoxic injury. It often results from non-cardiac factors (decreased blood volume, impaired venous return, vasodilation), is progressive, phasic and is relieved primarily by SNS reflex. While both the nephrotic syndrome and circulatory shock are extremes, the pregnant diabetic NOD mouse shares features without becoming fulminant. With the SNS likely already activated in early gestation to effect fluid retention, the mid to late gestation metabolic demands may overwhelm maternal regulatory systems, resulting in maladaption.

A notable observation in this study was the high survival rate of the offspring born to diabetic NOD dams. We previously reported high fetal resorption rates with accompanying morbidities (including mostly neural tube defects and patterning disturbances), when less supportive care was provided to diabetic dams. In our previous study, we established that diabetic NOD mice have significantly impaired spiral artery remodeling that could mediate placental insufficiency leading to fetal growth restriction [13]. However, using other mice in which no SA remodeling occurs (alymphoid NK-T-B- mice of genotype Rag2−/−Il2rg−/−) we established that placental and fetal hypoxia and growth insufficiency are not direct results from the SA remodeling deficit [15,28,29]. These findings elevate the importance of the change in maternal hemodynamic phenotype of the diabetic NOD in promotion of live births.

This study underscores the concept of pregnancy as a physiological stress test, and illustrates that consequences of impaired cardiovascular adaptation are not simply hypertensive responses. Persistence of the abnormal phenotype post-partum strongly supports the concept of permanent, gestationally-induced vascular dysfunction. Such vascular changes are likely to occur in humans, as described in preeclampsia studies [1,30]. However, at this time, few studies have been conducted in post-partum diabetic women to assess the vasculature, although advancing retinopathy and renal lesions have been documented [2–4,6]. Pregnant, diabetic NOD mice represent a model that exhibits progressive failure of both cardiovascular and renal systems after mid-gestation, changes that persist following successful delivery of live pups. While understanding of the full scope of the alterations occurring in maternal circulatory mechanisms and required for preservation of fetal circulation remain to be achieved, the findings from study of this animal model provide new insights into cardiovascular complications in diabetic pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Mean arterial pressure (MAP; n=4, white circles) and heart rate (HR; n=4, black circles) of non-pregnant diabetic NOD mice (with mean blood glucose 30.2±1.7mmol/L). Data is averaged over a 24-hour period, presented as mean±SEM.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Canadian Foundation for Women’s Health and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). SDB is supported by CIHR and BAC is supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

We wish to acknowledge Drs. John Fisher and Colin Funk for their continuing equipment support. We wish to thank Michael Bilinski, Jonathan Gravel and Dave Beseau for technical assistance.

SDB, MAA and BAC designed the experiment. SBD, VFB, SD, EVK, MAA and BAC analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the article and/or revised the article and had final approval.

Abbreviations

- DAP

diastolic arterial pressure

- gd

gestation day

- HR

heart rate

- Ifng

interferon gamma

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- NK

natural killer

- NOD

non-obese diabetic

- PP

pulse pressure

- SA

spiral artery

- SAP

systolic arterial pressure

- scid

severe combined immune deficiency

- T1DM

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- uNK

uterine natural killer

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Smith GN, Walker MC, Liu A, Wen SW, Swansburg M, Ramshaw H, White RR, Roddy M, Hladunewich M Pre-Eclampsia New Emerging Team (PE-NET) A history of preeclampsia identifies women who have underlying cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:58.e1–58.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaaja R. Vascular complications in diabetic pregnancy. Thromb Res. 2009;123 (Suppl 2):S1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persson M, Norman M, Hanson U. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in type 1 diabetic pregnancies: A large, population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2005–2009. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauszus FF, Klebe JG, Rasmussen OW, Klebe TM, Dorup J, Christensen T. Renal growth during pregnancy in insulin-dependent diabetic women. A prospective study of renal volume and clinical variables. Acta Diabetol. 1995;32:225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00576254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howarth C, Gazis A, James D. Associations of Type 1 diabetes mellitus, maternal vascular disease and complications of pregnancy. Diabet Med. 2007;24:1229–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haeri S, Khoury J, Kovilam O, Miodovnik M. The association of intrauterine growth abnormalities in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus complicated by vasculopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:278.e1–278.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlin A, Alfirevic Z. Physiological changes of pregnancy and monitoring. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:801–823. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Mook WN, Peeters L. Severe cardiac disease in pregnancy, part I: hemodynamic changes and complaints during pregnancy, and general management of cardiac disease in pregnancy. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:430–434. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000179807.15328.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu Q, Levine BD. Autonomic circulatory control during pregnancy in humans. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:330–337. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganzevoort W, Rep A, Bonsel GJ, de Vries JI, Wolf H. Plasma volume and blood pressure regulation in hypertensive pregnancy. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1235–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000125436.28861.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jauniaux E, Burton GJ. Villous histomorphometry and placental bed biopsy investigation in Type I diabetic pregnancies. Placenta. 2006;27:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjork O, Persson B, Stangenberg M, Vaclavinkova V. Spiral artery lesions in relation to metabolic control in diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63:123–127. doi: 10.3109/00016348409154646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke SD, Dong H, Hazan AD, Croy BA. Aberrant endometrial features of pregnancy in diabetic NOD mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:2919–2926. doi: 10.2337/db07-0773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross V, Tank J, Partke HJ, Plehm R, Diedrich A, da Costa Goncalves AC, Luft FC, Jordan J. Cardiovascular autonomic regulation in Non-Obese Diabetic (NOD) mice. Auton Neurosci. 2008;138:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke SD, Barrette VF, Bianco J, Thorne JG, Yamada AT, Pang SC, Adams MA, Croy BA. Spiral Arterial Remodeling Is Not Essential for Normal Blood Pressure Regulation in Pregnant Mice. Hypertension. 2010 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heresztyn T, Nicholson BC. A colorimetric protein phosphatase inhibition assay for the determination of cyanobacterial peptide hepatotoxins based on the dephosphorylation of phosvitin by recombinant protein phosphatase 1. Environ Toxicol. 2001;16:242–252. doi: 10.1002/tox.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leiter EH. The NOD mouse: a model for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001;Chapter 15(Unit 15.9) doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1509s24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomsen JL, Hansen TP. Lipids in the proximal tubules of the kidney in diabetic coma. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21:416–418. doi: 10.1097/00000433-200012000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichi RB, Farah V, Chen Y, Irigoyen MC, Morris M. Deficiency in angiotensin AT1a receptors prevents diabetes-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1184–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00524.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira VL, Moreira ED, Farah VD, Consolim-Colombo F, Krieger EM, Irigoyen MC. Cardiopulmonary reflex impairment in experimental diabetes in rats. Hypertension. 1999;34:813–817. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reyes AA, Karl IE, Kissane J, Klahr S. L-arginine administration prevents glomerular hyperfiltration and decreases proteinuria in diabetic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;4:1039–1045. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V441039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bucci M, Roviezzo F, Brancaleone V, Lin MI, Di Lorenzo A, Cicala C, Pinto A, Sessa WC, Farneti S, Fiorucci S, Cirino G. Diabetic mouse angiopathy is linked to progressive sympathetic receptor deletion coupled to an enhanced caveolin-1 expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:721–726. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122362.44628.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Donnell MP, Kasiske BL, Keane WF. Glomerular hemodynamic and structural alterations in experimental diabetes mellitus. FASEB J. 1988;2:2339–2347. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.8.3282959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satchell SC, Tooke JE. What is the mechanism of microalbuminuria in diabetes: a role for the glomerular endothelium? Diabetologia. 2008;51:714–725. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0961-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ang C, Lumsden MA. Diabetes and the maternal resistance vasculature. Clin Sci(Lond) 2001;101:719–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng J, Sbaiti R, Kwee H, Abendroth CS, Cheriyath P. An unusual case of lambda light chain amyloidosis presenting with hypotension and nephrotic syndrome in a 36-year-old female. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:725–726. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogi M, Kojima S, Kuramochi M. Effect of postural change on urine volume and urinary sodium excretion in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:41–48. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9428450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leno-Duran E, Hatta K, Bianco J, Yamada AT, Ruiz-Ruiz C, Olivares EG, Croy BA. Fetal-Placental Hypoxia Does Not Result from Failure of Spiral Arterial Modification in Mice. Placenta. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burke SD, Barrette VF, Gravel J, Carter AL, Hatta K, Zhang J, Chen Z, Leno-Duran E, Bianco J, Leonard S, Murrant C, Adams MA, Anne Croy B. Uterine NK cells, spiral artery modification and the regulation of blood pressure during mouse pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:472–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granger JP, Alexander BT, Llinas MT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia/hypoxia with microvascular dysfunction. Microcirculation. 2002;9:147–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mean arterial pressure (MAP; n=4, white circles) and heart rate (HR; n=4, black circles) of non-pregnant diabetic NOD mice (with mean blood glucose 30.2±1.7mmol/L). Data is averaged over a 24-hour period, presented as mean±SEM.