Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our goal was to define mechanisms that protect murine pregnancies deficient in spiral arterial (SA) remodeling from hypertension, hypoxia and intra-uterine growth restriction.

STUDY DESIGN

Micro-ultrasound analyses were conducted on virgin, gestation day (gd)2, 4, 7, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 and postpartum BALB/c (WT) mice and BALB/c-Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice, an immunodeficient strain lacking SA remodeling.

RESULTS

Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− dams had normal SA flow velocities, greatly elevated uterine artery flow velocities between gd10-16 and smaller areas of placental flow from gd14 to term than controls. Maternal heart weight and output increased transiently. Conceptus alterations included higher flow velocities in the umbilical-placental circulation that became normal before term and bradycardia persistent to term.

CONCLUSION

Transient changes in maternal heart weight and function accompanied by fetal circulatory changes successfully compensate for deficient SA modification in mice. Similar compensations in humans may contribute to post-partum pregnancy gains elevated risk of cardiovascular disease associated with preeclampsia.

Keywords: fetal programming, lymphocyte biology, mouse pregnancy, post-partum cardiovascular risk, preeclampsia

INTRODUCTION

Normal pregnancy significantly changes reproductive tract and systemic circulations to accommodate growth and metabolic demands of developing conceptuses. In species with hemochorial placentation, such as humans, uterine vascular changes include increased permeability, angiogenesis and structural remodeling of most spiral arteries (SA) to reduce vasoactivity and increase capacity. 1, 2 In humans, inadequate modification of decidual and myometrial SA is often accompanied by preeclampsia (PE) and/or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). 3, 4 SA remodeling is progressive and involves loss of vascular smooth muscle coat and elastic lamina, mural invasion by trophoblast cells that deposit non-vasoactive fibrinoid and transient replacement of vascular endothelial cells by intravascular trophoblast. 2, 5 In humans, SA remodeling normally occurs during first and second trimester with ~2/3 of these vessels dilating 5–10 fold. SA remodeling slows maternal blood flow, minimizes turbulence and optimizes exchange time with the fetal circulation. 6 Decidual lymphocytes, mainly uterine natural killer (uNK) cells, contribute to early stages of decidual SA transformation through cytokine secretion 7–10 as do mechanical flow properties such as shear forces and pressure. 11

The systemic circulatory changes of early normal pregnancy include increases in cardiac output, blood volume and glomerular filtration rate 12, 13 that result in an overall maternal state of high blood flow with low vascular resistance. Inadequate or excessive cardiovascular adaptations before week 20 of pregnancy predict complications. 14 Cardiac disease occurs in 1% to 4% of pregnancies in women with no pre-existing heart abnormalities. Further, women who experience adverse outcomes such as PE, carry increased risks for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases into later life. 15 Thus, identifying links between uterine vascular remodeling and systemic cardiovascular abnormalities is critical for appropriate management of human gestational complications. 16 Early in normal human and mouse pregnancies, mean arterial blood pressure decreases slightly or is stable. 17, 18 This indicates that gains in uterine flow are more attributable to morphological remodeling of uterine arteries than to alterations in their smooth muscle tone. 19

Mouse models have promoted understanding of mechanisms regulating gestational changes to the cardiovascular system. 20 Comparisons of micro-ultrasound measurements of placental growth and blood flow velocity between normal and mutant mice (i.e. Nos3−/−) revealed significant similarities to human pregnancies. 20–22 Those mouse strains examined by micro-ultrasound have not lacked SA modification, a characteristic of mice deficient in uNK cells. This phenotype is reversible by transplantation of marrow genetically deficient for T and B cell differentiation (ie, NK+, T−B− marrow). 10 SA modification is histologically-detected between gestation day (gd)9-10 of 19–20 day mouse pregnancy, 10 a time-point recognized for allantoic fusion with the chorionic plate to open placental circulation. 23 Here, we examine hemodynamic features of wildtype BALB/c+/+ (WT; i.e. NK+T+B+) and alymphoid (deficient in NK, T and B cells (NK−T−B−)) BALB/c-Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice before, across and after pregnancy using micro-ultrasound. Unlike most patients with impaired SA remodeling, 24 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− dams with unmodified SA have normotensive pregnancies without detectable elevation in hypoxia of placental, fetal or maternal tissue. 25 They also show no elevation in fetal loss and their offspring are not growth impaired. 18, 25 While these interspecies outcome differences strongly implicate lymphocyte-based immunity in progression of human gestational complications accompanying incomplete SA remodeling, they do not explain the physiological mechanisms that provide normoxic placental, fetal and maternal tissues in the absence of maternal hypertension. 18 We now report specific cardiovascular differences between pregnant Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− and WT females. These differences include greater uterine arterial blood velocity and increased heart weight and performance, especially over the second half of pregnancy. These maternal adaptations are accompanied by lower fetal heart rates and reduced placental vascular space.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Mice

This study used 8–10 week old mice (39 BALB/c+/+; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME and 44 in-house bred BALB/c-Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/−). Timed matings were prepared using syngeneic males; copulation plug detection was dated gd0. An ultrasound examination was performed once per female either before mating (non pregnant, NP), at gd2, 4, 7, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 or at 48-hour postpartum (PP) (table 1). Females were then euthanized, weighed and their organs were immediately dissected, weighed and processed for other purposes. Wet weights were used to calculate organ to body weight (BW) ratios. Pregnancies were confirmed pre-implantation (gd2-4) by post mortem embryo flushing; from gd7-18, by viable implantation site visualization. Mean litter sizes in this study were not significantly different between genotypes. 24 All procedures were conducted under Animal Utilization Protocols approved by the Animal Care Committee, Queen’s University.

Ultrasound Procedures

Anaesthetized (inhaled isoflurane) mice, after fur removal (Nair; Church & Dwight Co., Inc.), were taped (Transpore, 3M) onto the instrument platform. A thick layer of pre-warmed coupling gel (Ecogel 100; ECO-MED Pharmaceutical, ON, Canada) was applied over the area to be imaged using a 40-MHz transducer probe (Vevo 770, VisualSonics Inc., ON, Canada). 22, 26 Body temperature was maintained at 36–37°C by the warmed platform. Maternal heart and respiration rates (ECG/Tm/Resp) were collected using a Physiological Controller Unit.

For maternal uterine artery (UtA) power Doppler scans, bladder was first identified, then the probe was moved to locate the uterine artery arising from the common iliac. 22 SA flows, characterized by pulsed waveforms, were imaged at the mesometrial decidual edge in 2–4 implantation sites of each gd10-18 pregnancy. Peak systolic velocities of fetal umbilical arteries (UmA) were recorded before these arteries entered the placenta and branched into chorionic plate arteries (CPA) that run across the placental surface and branch into the major intraplacental arteries (IPA) in developing primary villi. After UmA study, peak systolic velocity of CPA and IPA flows were recorded in 3–5 locations/implantation site. 22, 23 Maternal left renal artery (RA) flow velocity waveform was recorded to assess systemic blood velocity. For maternal data, 3–6 different females of each genotype were imaged per time-point (i.e. no repeated study was made on any animal). For conceptus measurements, 6–15 implantation sites were averaged per presented time-point. Waveforms were analyzed offline.

Motion modulation (M-mode) images were constructed to evaluate maternal heart chamber dimensions at various times throughout the cardiac cycle. 3-D power Doppler data were used to estimate placental volume and structure. The Doppler beam angle was set at 27° to acquire consistent data. Doppler velocity waveforms from UtA, SA, UmA, RA, IPA and CPA were captured using brightness-mode (B-mode) imaging with the following settings: pulse repetition frequency, 10 kHz; wall filter, 100 Hz; display window, 2000 ms; sound speed, 1540 m/s; Doppler gain, 5.00 dB. The display range of the 3D-Doppler measurements of placental volume and vascular density was 19 dB (minimum)–30 dB (maximum).

Data management and analysis

Instrument software packages provided the analyses. Peak systolic velocity, mean velocity and end-diastolic velocity were measured from Doppler images. Doppler indices calculated to interpret the data were:

Cardiac measurements were obtained from M-mode data (see supplementary materials). Data are presented as mean (±SD). Comparisons were performed by Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA where appropriate for SPSS 13 analysis. A p-value of < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Maternal circulations in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− pregnancies

1) Renal arterial flow patterns of WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice before, during and after pregnancy

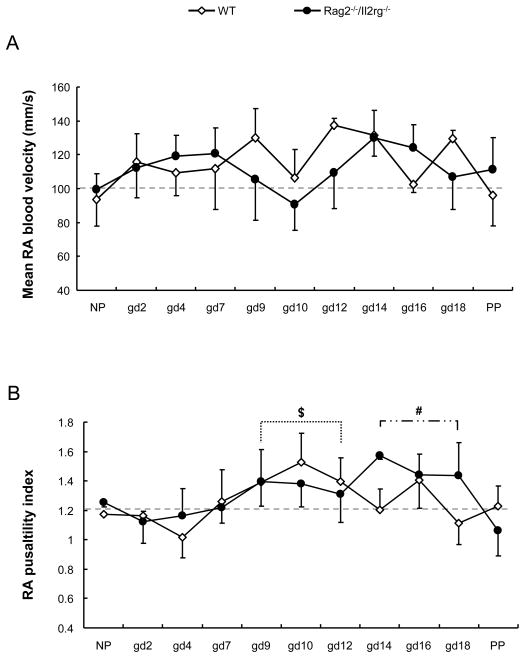

To evaluate the systemic circulation, maternal renal arterial velocity was studied in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice (summarized data Fig 1A; full data supplementary Fig 1). Renal arterial flow velocity was similar in both strains before mating, suggesting similar homeostatic states. For both strains, renal arterial blood velocity increased at gd2 (p < .05), remained statistically stable to gd7 and dropped to a nadir at gd10, the first day of placental circulation. Velocities then rebounded with a slightly delayed time course in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− (peak at gd12 in WT; gd14 in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− (p < .05, compared to other gd)). Renal arterial pulsatility indices rose after conceptus implantation and peaked at gd9-12 in WT (p < .05, compared with NP). But in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/−, the peak renal arterial pulsatility index was delayed to gd14-18. (Fig 1B). At given time point, there were no statistical differences for renal arterial pulsatility indices between two strains (Fig 1B).

Fig 1.

Renal arterial flow pattern. Left maternal renal artery (RA) flow velocities across pregnancy in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice. RA blood flow velocities were recorded by micro-ultrasound and data were analyzed for mean velocity (A) and pulsatility index (PI, B) to assess hemodynamic characteristics in mice with (WT) or without (Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/−) SA modification. 3–6 pregnant mice were studied at each time point. $, p < .05 comparing indicated gd to NP WT mice. #, p < .05 comparing indicated gd to NP Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice.

2) Uterine arterial flow patterns of WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice before, during and after pregnancy

Uterine blood delivery is bidirectional from ovarian and uterine arteries. 1 Because WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice had similar renal arterial velocities, a vessel arising close to or upstream of the ovarian artery, ovarian arterial study was not conducted. Uterine arterial velocity was estimated from vessels arising from the internal iliac (Fig 2A, B). Mean uterine arterial velocities were similar between WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− before pregnancy, at pre-implantation (gd2), peri-implantation (gd4) and term (Fig 2C). For WT mice, the first Doppler-detected uterine arterial flow change was a gd9 increase by comparing with non pregnant state (Fig 2C and sFig 2A). This established a value stable to gd12, when spiral artery modification is complete histologically. WT uterine arterial velocity was characterized by a second statistically distinct gain at gd14. This velocity continued until parturition (sFig 2A). Uterine arterial flow velocity of Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− matched WT mice to gd4 and at gd18 and post partum. It increased earlier than WT (gd7), rose more steeply (doubling that of WT by gd14) then declined (Fig. 2C, sFig 2B).

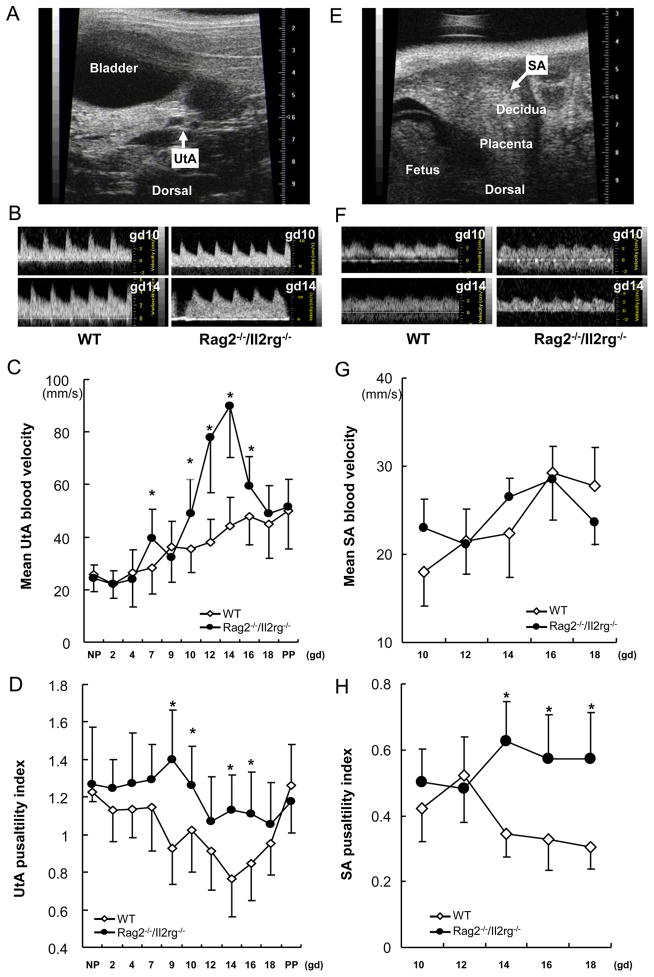

Fig 2.

Maternal arterial flow patterns. WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− uterine artery (UtA) and spiral artery (SA) flow velocities and pulsatility indices across pregnancy. Uterine arterial (left panel) and SA (right panel) flow velocities were recorded by micro-ultrasound and analyzed. Representative images illustrate the probing locations and typical waveforms for study of the uterine arterial (A, B) and SA (E, F) in gd12 WT mice with ventral abdomen uppermost in the image. Mean velocity (C, G) and pulsatility index (PI; D and H) were calculated for each vessel to assess maternal hemodynamic characteristics of WT or Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice. Multiple implantation sites (2–4) from each of (3–6) pregnant mice were scanned per time point. *, p < .05 between WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− at given time point.

Calculated resistance indices of WT uterine arteries (PI, RI, S/D ratio) had downwards post-conception trends to gd14 (37% decrease of PI) then gradually returned to pre-pregnancy levels (Fig 2D; supplementary Fig 2C, D). In virgin Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− females, the uterine arterial pulsatility index of was similar to that of WT but, after mating, increased to gd9, declined to gd12 then was stable to post partum. Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− uterine arterial pulsatility index (Fig 2D) and resistance index (supplementary Fig 2C) significantly exceeded WT on gd9, 10, 14, 16. These data reveal anomalous Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− uterine arterial flow velocities over mid to late gestation that normalized peripartum (gd19).

3) Spiral arterial flow patterns of WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice during pregnancy

Murine decidual SA development begins after implantation. The earliest SA waveform our system identified was at gd10 when WT mean velocity was 18 mm/s (Fig 2E–G). This increased to term with significant elevation at gd16-18 with velocities reaching 32–35 mm/s (Fig 2G, supplementary Fig 2E). Gd10 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− SA flow velocity was 23 mm/s. Velocity increased at gd14-16 (p < .05) and at gd18 dropped to baseline (Fig 2G; supplementary Fig 2F). There were no cross strain differences in mean velocities of SA (Fig 2G) but resistance indices (PI, RI and S/D ratios) at gd14, 16 and 18 were higher for Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− than WT (Fig 2H, supplementary Fig 2G, H).

Umbilical and placental circulations in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− pregnancies

Placental circulation follows fusion of the allantois (umbilical cord progenitor) with the chorion and development umbilical arterial waveforms without end diastolic velocity were clearly detected by gd10 (Fig 3A–C). Patterns for umbilical arterial peak systolic velocity were similar in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/−; velocities increased at gd12 (p < .05, compared to gd10 for each strain), gd14 (p < .05, compared to gd10 or 12) and were maintained until term (Fig 3D). Gd12-16 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− velocities were greater (p < .05) than WT.

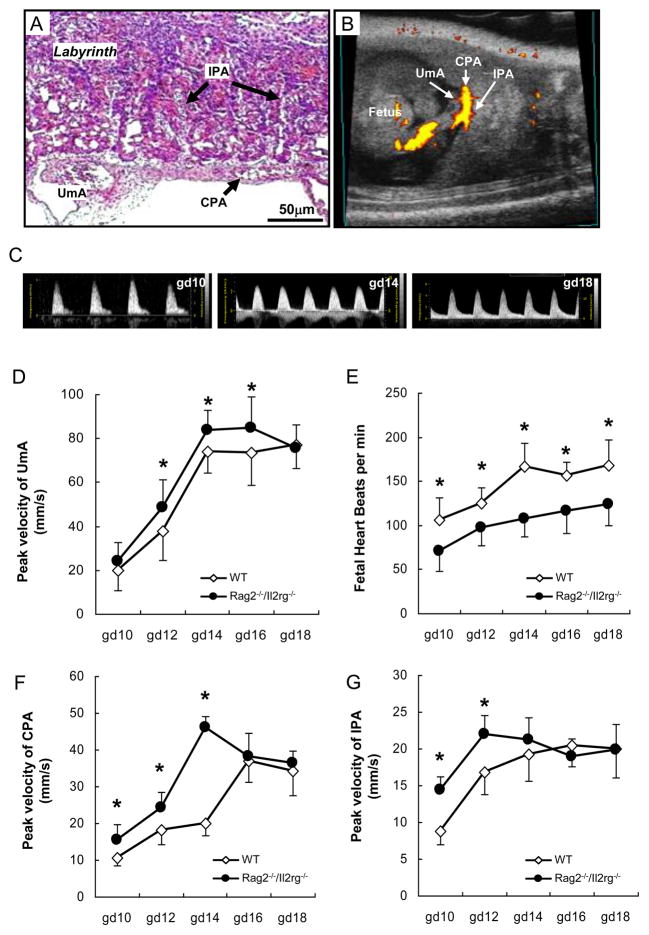

Fig 3.

Umbilical-placental circulations. Umbilical-placental circulations and heart rates of gd10-18 WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice. Umbilical arteries (UmA), chorionic plate arteries (CPA) and intraplacental arteries (IPA) were resolved and studied. A representative gd12 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− histological section (H&E stained) of the scanned tissue with the resolved vessels is given in (A). The fetal aspect of the placenta is towards the bottom of the image. A clockwise 90° rotation of this section aligns it with the power Doppler image (B) of a gd12 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mouse. Representative UmA waveforms of Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mouse were showed (C). Based on Doppler imaging data, peak UmA (D), CPA (F) and IPA (G) flow velocities and fetal heart rates (E) were calculated. Multiple (2 – 4) implantation sites were studied from each of 3–6 pregnant mice at each gd. *, p < .05 between WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice at given time point.

Heart rates (estimated from umbilical artery pulses) were higher in WT than Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− fetuses from midpregnancy to birth (p < .05, Fig 3E). WT fetal heart rates increased significantly at gd12 and gd14, then were stable at 156–167 beats/min until birth. Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− fetal heart rates rose significantly only at gd12 to 98 beats/min (p < .05) and remained stable until term. These data indicate Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− fetuses differ from WT and suggest they use heart enlargement and/or greater stroke volume rather than increased beating rate to support mid-pregnancy placental flow. To address placental circulation, chorionic plate and intraplacental arterial velocities were assessed (Fig 3F, G). From gd10-18, these waveforms had progressively increasing end-diastolic velocities indicating they were branches from umbilical not spiral arteries. In both strains, chorionic plate and intraplacental arterial velocities increased during pregnancy. Compared to WT conceptuses, Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− had higher chorionic plate (gd10-16) and intraplacental (gd10-14) arterial velocities.

Analyses of WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placental structure

Mouse placenta is recognized by its echo image density. Placental size and vascularity (percent placental space with detectable flow) were calculated from 3-D power Doppler images (Fig 4A). WT placental volume was 7.0 mm3 at gd10. This increased rapidly to gd14 (p < .05 compared to gd10), then more slowly to term (Fig 4C). The Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placental growth pattern was similar but smaller volumes were estimated at gd10, 12 and 16 (p < .05, Fig 4C). For both strains, placental vascularities were similar at gd10 and 12, sharply increased at gd14 (p < .05, compared to gd10, 12), then stable until term (Fig 4D). Gd12-18 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placentas had significantly less functional vascular space than WT (p < .05, Fig 4D).

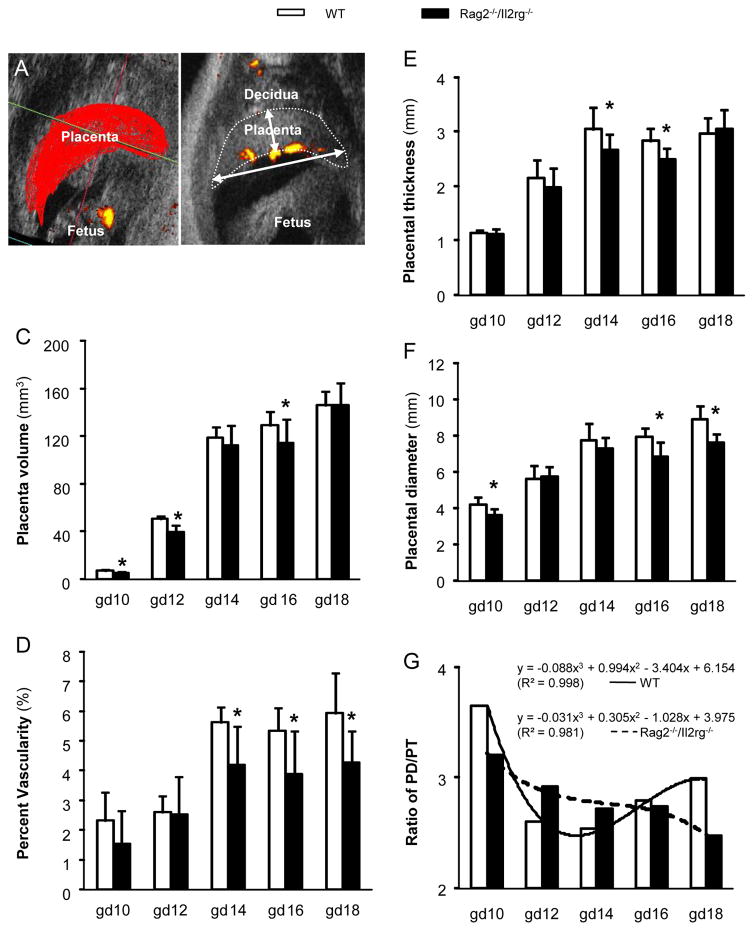

Fig 4.

Placental ultrasound indices. 3D Doppler images of gd10-18 WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice implantation sites were acquired to measure placental volume (A, C). Percent vascularity (PV) was derived from 3D volumes and used to evaluate Doppler detected flow within the placenta (A, D). Placental diameter and thickness were measured at maximum mid-section of each recorded 3D image (B, E, F). Placental diameter to thickness ratios (PD/PT) are presented, together with their polynomial regression curves and formulas (G). (A) shows multiple manually scanned outlines (step size=0.1 mm) of a gd12 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placenta complied to estimate volume. The yellow feature is the pulsatile fetal heart flow captured by 3D Doppler. (B) is a representative image illustrating the method of data collection for placental diameter and thickness measurements using a gd12 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placenta. Flows in the UmA, CPA and IPA are seen as yellow on the placenta which is outlined by a dotted line. Two-4 implantation sites from each of 3–6 mice were studied at each time point. *, p < .05 between WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice at given time point.

2-D measurements of maximum placental thickness and diameter revealed additional placental differences (Fig 4B). Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− were thinner than WT placentae at gd14-16 and narrower than WT placentae at gd10, 16 and 18 (Fig 4E, F). Geometric shapes of growing placentae were compared as ratios of measured placental diameter and thickness. Ratios for Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placentae decreased linearly from gd10 to gd18 but those for WT placentae formed a reversed parabolic curve with its lowest points at gd12, 14 (Fig 4G). These data indicate that WT placental growth is not linear with gestational age and that, in addition to their unusual hemodynamic patterns, Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− use different placental growth strategies along each axis.

Maternal body and organ mass in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice before, during and after pregnancy

As published, 27 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− females are larger than aged matched WT before mating and over pregnancy (Δ7.9-12.8 g; p < .05, Fig 5A; supplementary table 1). Pregnancy weight gain was significant in WT females by gd12 but by gd10 in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− females (p < .05 compared with corresponding NP). By peri-partum gd18, WT dams had gained 10.4g and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− females 15.0 g (46% and 50% of pre-pregnancy weights respectively).

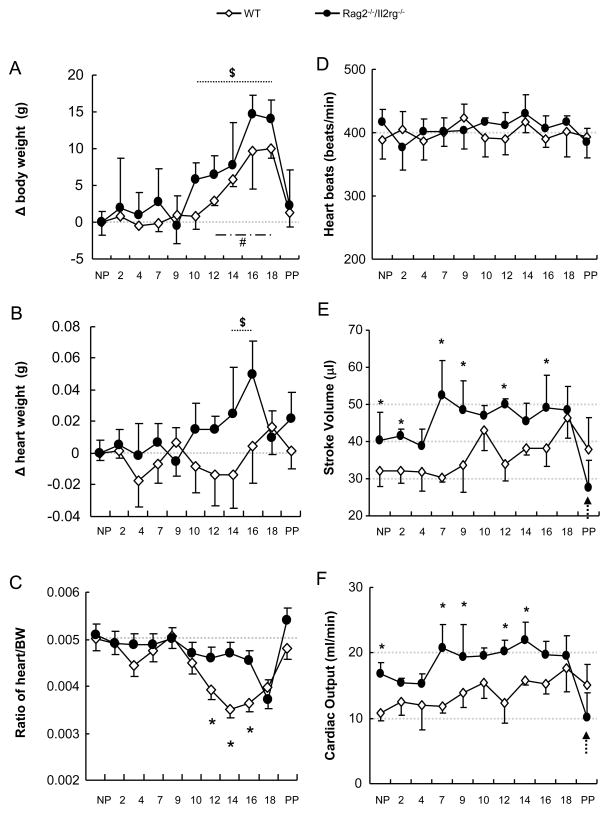

Fig 5.

WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− heart assessments over pregnancy. Changes (Δ) from pre-conception body (A) and heart weight (B) and ratios of body to heart weight (C) are shown over pregnancy for WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− dams. Left ventricle (LV) parameters of WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− dams were assessed across pregnancy by M-mode ultrasound scanning. Heart rates during ultrasound examination are presented (D). Based on collected M-mode data, LV stroke volume (SV; E) and cardiac output (CO; F) were calculated. SV and CO of Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice dropped significantly postpartum (PP; arrows). $, p < .05 comparing indicated gd to WT NP. #, p < .05 comparing indicated gd to Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− NP. *, p < .05 comparing WT with Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice at matched gd. n=3–6 at each studied time point.

WT hearts were significantly smaller than Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− hearts before, during and after pregnancy (Δ 0.03–0.09 g; p < .05, Fig 5B and supplementary table 1). WT heart mass did not change over pregnancy. Thus, the WT maternal heart/BW ratio decreased significantly over gd12-18 as BW increased. Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− hearts were significantly heavier at gd14-16 than before or earlier in pregnancy (p < .05, Fig 5B). This gain sustained Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− heart to body weight ratios between gd12 to 16 (p < .05, Fig 5C). These data suggest circulatory maintenance in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− is achieved by transient, midgestational cardiac enlargement. Other organs (liver, kidney, spleen) changed proportionally between strains (supplementary Fig 3).

Maternal cardiac functions in WT and Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice before, during and after pregnancy

Maternal cardiac functions were assessed by left ventriclar measurements in anesthetized mice with similar heart rates (394±18 beats/min WT; 406±14 beats/min Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/−, p > .05; Fig 5D). Differences were more apparent in diastole than systole. During pregnancy, no significant changes occurred in WT left ventricle dimension or volume (systole or diastole; supplementary Fig 4). Although pre-conception Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− hearts were heavier than WT, left ventricle dimension and volume did not differ signficiantly from WT. The Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− ejection fraction was much greater than WT (supplementary Fig 4), resulting in greater stroke volume (Δ=8.3 μl) and cardiac output (Δ=6.1 ml/min) in pre-conception Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− than in WT (p < .05, Fig 5E, F). During pregnancy, Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− stroke volume peaked at gd7 and was 1.7 fold greater than WT. WT stroke volume and cardiaac output peaked later at gd10. By peri-partum gd18, stroke volume and cardiac output were identical in the two strains. A huge post-partum drop to values significantly below pre-pregnancy (27.7 μl for Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− and 37.9 μl for WT; Fig 5E) occurred in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− left ventricular stroke volume and cardiac output (43% vs gd18) versus WT (18% vs gd18), suggesting acute reduction in resistance and/or cardiac myopathy.

COMMENT

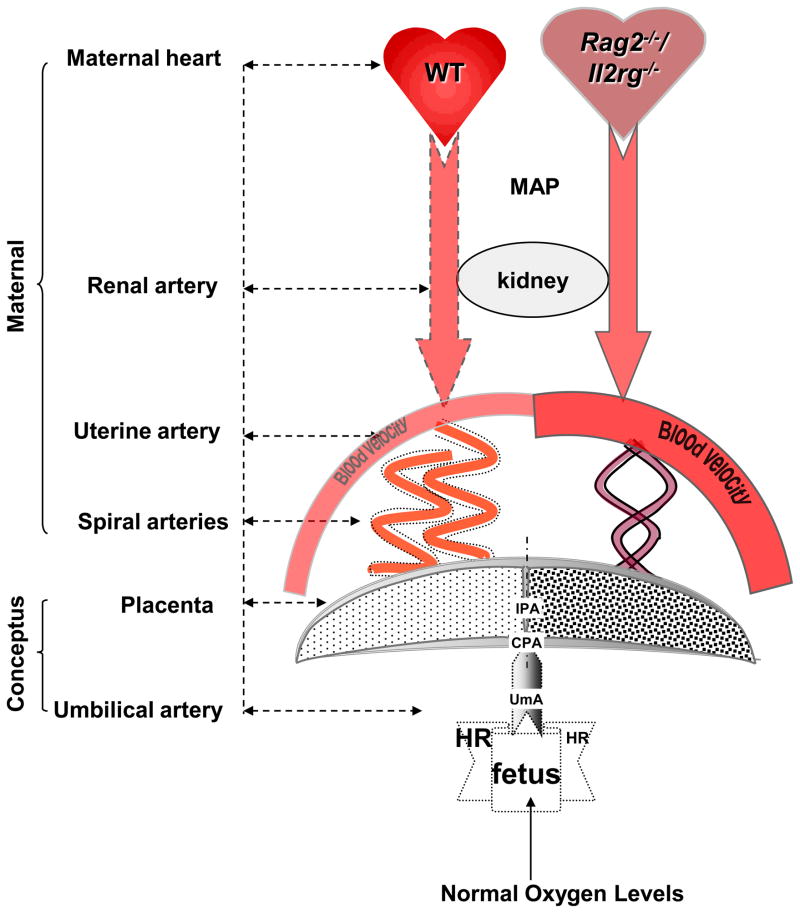

This study identified maternal and fetal cardiovascular alterations as primary events induced in pregnant mice by deficient SA modification. Using a full time-course study of pregnancy, we established (summarized in Fig 6) that most of these changes are initiated from the time point at which SA modification becomes histologically detectable (gd10). The pattern of uterine arterial velocity in WT mice resembled that of normal human pregnancy with progressively increasing velocity and decreasing resistance over gestation. In women, these changes are attributed to an almost doubling of uterine arterial diameter accompanied by alternations in collagen and elastin. 1 Increasing uterine arterial flow, used with other tests to identify human fetuses at increased risk for adverse outcome, 28, 29 is thought to reflect defective SA modification and increased downstream resistance. 30 Our data in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− support this interpretation and expand it to show that altered maternal and fetal cardiac functions accompany and may precede the gd10-16 gains in uterine arterial flow velocity. For example, changes from normal were present in some uterine arterial parameters at gd7-9 in mice with unmodified SA and their fetuses had depressed heart rates at gd10. The cardiovascular changes in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− appeared highly coordinated, successful compensations that returned maternal and placental circulations to normal values prior to birth. Elevated downstream Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placental resistance, as estimated from SA velocities, was present from gd14-18. Elevated downstream Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placental vascular resistance, as estimated from fetal circulatory parameters, was present from gd10-16. Peak uterine arterial velocity occurred at gd14, a time after normalization of flow velocity in small fetal placental vessels (IPA) but coincident with normalization of flow velocity in chorionic plate atery. A large drop in uterine arterial velocity occurred between gd14-16, an interval during which the umbilical circulation also normalized. It was noted that at postpartum, uterine artery velocities were higher than non pregnant state though their pulsatility indices became normal. Healthy involuted placental bed was characterized by a disappearance of trophoblasts and completely thrombosed spiral arteries, those pathological changes after delivery need enough blood supply via uterine artery to maintain normal puerperium recovery.

Fig 6.

Summary. Doppler findings at mid to late gestation stage in mice whose implantation sites do not differ in levels of oxygenation or fetal health status. To the left are control findings for WT mice with spiral artery (SA) modification. To the right are experimental findings for Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− without SA remodeling. Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice have a large heart that hypertrophies but their pregnancy and placentation are healthy; WT heart does not gain weight. Blood flow velocities are equivalent in RA but greatly elevated in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− uterine artery (illustrated as wider, darker arch) though hyperoxygenation detected in kidney medulla. SA flow velocities are similar although WT SA are modified (dotted lines). Resistance is increased in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− SA after gd12. The heart rates (HR) of Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− fetuses are lower than WT, pumping blood at higher velocities in UmA, CPA and IPA. This suggests Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− fetuses use larger stroke volumes and cardiac outputs that would induce cardiac hypertrophy. Although both strains had comparable placental volumes, less space is occupied by flow in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice by gd14, suggesting impaired angiogenesis. UmA, umbilical artery; CPA, chorionic plate arteries; IPA, intraplacental arteries.

Fetal bradycardia was the only alteration persisting until birth. The lower Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− heart rate and elevated placental circulatory resistance probably reflect increased fetal cardiac output and induced cardiac hypertrophy. Current understanding of the “developmental origins hypothesis” suggests that such fetal heart changes would be permanent (ventricles develop between gd11-18 31) and would elevate risk for cardiovascular pathology later in life. Gains in maternal and fetal cardiovascular functions likely explain why placental hypoxia is not elevated in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− over that seen in normal mice. It would also explain why perfusion of the maternal renal medulla of Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− exceeds that measured in normal pregnant mice. 25

Absence of restriction to Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placental oxygenation and growth should account for the absence of fetal growth restriction in this strain despite its incomplete SA modification. Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placentae however, were not entirely normal; they contained less vascular space than normal placentae. Whether this reflected maternal and/or fetal change could not be determined. Coan et al. reported for normal mice that maternal labyrinthine space grew between gd13-15 but subsequent growth was exclusively from the conceptus. 32 Because our interval of reduced percentage of vascularity is gd14-18, we expect reductions occurred in both maternal and fetal placental vascularity. Lack of Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placental vascularity was counter-balanced by greater placental blood flow velocity than normal. This may provide equivalent nutrition for Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− conceptuses. Future studies with newer techniques such as microbubbles will be needed to estimate whether total flow volumes are equivalent in placentae supported by modified and unmodified SA. Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placentae had minor intervals of axis growth deficiency that gave them a growth trajectory distinctly different from that of placentae supported by modified SA. By the end of the middle 3rd of gestation, a thicker placenta was present in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− but ratios normalized by gd16, a finding confirming previous histological studies. Just before birth, the Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− placenta was thinner than normal. Because scanned implantation sites could not be reliably identified at postmortem, sexing of the fetuses was not undertaken and future studies will be needed to determine if, as in humans, male and female placental axes differ. 33

Less well answered by this study is why hypertension with renal impairment similar to preeclampsia is not observed after failure of SA modification in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice. It is not known at present what physiological effects arise from superoxygenation of the renal medulla and if this provided renal protective or systemic blood pressure regulating mechanisms over pregnancy. Absence of lymphocytes Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice is the key feature that permitted identification of maternal and fetal cardiac changes as responses to incomplete SA modification. Our previous data illustrated that in mouse model, absence of tissue remodeling is not the direct reason for gestational hypertension. 18 Lymphocytes may be sensors of changes in flow parameters or in endothelial cells responding to altered flow parameters. Alternatively, lymphocytes may be amplifiers of changes expressed by endothelial cells and/or circulating cells such as macrophages or neutrophils and/or by vascular smooth muscle and other vessel supporting cells. The hemodynamic and angiogenic influences lymphocytes and their products are emerging areas and further investigations are needed to understand how central their roles are for initiation and progression of preeclamptic pathology. 8, 34–37

Impaired SA remodeling is a key feature found amongst the “great obstetrical syndromes” .38 In mice, we clearly show that, over the normal term of pregnancy, a maternal-fetal partnership exists that can resolve the hemodynamic changes imposed by this arterial pathology. The “costs” for these murine circulatory adjustments appear to be much less severe than the costs in humans. Cost may be almost nil for the mouse mother, unless the transient gain in heart weight results in subsequent inflammation or scarring. 39 The fetal mouse cost is likely cardiac hypertrophy and elevated risk for later cardiovascular disease. 40 Might our data suggest that development of therapeutic approaches for human pregnancies with impaired SA remodeling that prevent engagement of lymphocytes, promote their early disengagement or scavenging of their products would be beneficial in prolonging gestation and permitting physiological normalization of the maternal and fetal circulations near term? While Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− mice model only one component of human pregnancies complicated by incomplete SA modification, their study draws attention to the need to fully define the roles of lymphocytes in initiation and progression of pathology in human pregnancies complicated by incomplete SA modification and suggests that post pregnancy maternal and child cardiovascular risk elevation can be generated solely by this pregnancy complication in the absence of hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This work was supported by awards from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and Canada (#NGPIN3219-06), the Canada Research Chairs Program to BAC and a Province of Ontario/Queen’s Postdoctoral Fellowship to JHZ (#17691).

We thank Ms. Jalna Meens and Mr. Jeff Mewburn (Queen’s CRI Imaging Centre, Kingston, ON) for their technical assistance, Dr. Graeme N. Smith (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kingston General Hospital for helpful discussions and Ms. Valérié Barrette and the Animal Care staff of Queen’s University for their dedicated care our mice.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

PRESENTATION INFORMATION: Presented in abstract and poster form, SGI 2011, Miami Beach FL, March 16–19, 2011. Abstract S-103.

References

- 1.Osol G, Mandala M. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Physiology. 2009;24:58–71. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith SD, Dunk CE, Aplin JD, Harris LK, Jones RL. Evidence for immune cell involvement in decidual spiral arteriole remodeling in early human pregnancy. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1959–1971. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young BC, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:173–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzuca MQ, Wlodek ME, Dragomir NM, Parkington HC, Tare M. Uteroplacental insufficiency programs regional vascular dysfunction and alters arterial stiffness in female offspring. J Physiol. 2010;588:1997–2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Hanssens M. The uterine spiral arteries in human pregnancy: facts and controversies. Placenta. 2006;27:939–58. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta. 2009;30:473–82. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodring TC, Klauser CK, Bofill JA, Martin RW, Morrison JC. Prediction of placenta accreta by ultrasonography and color doppler imaging. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;0:1–4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.483523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lash GE, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Review: Functional role of uterine natural killer (uNK) cells in human early pregnancy decidua. Placenta. 2010;31:S87–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croy BA, Van Den Heuvel MJ, Borzychowski AM, Tayade C. Uterine natural killer cells: a specialized differentiation regulated by ovarian hormones. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:161–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitley G, Cartwright JE. Cellular and molecular regulation of spiral artery remodelling: lessons from the cardiovascular field. Placenta. 2010;31:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsiaras S, Poppas A. Cardiac disease in pregnancy: value of echocardiography. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2010;12:250–256. doi: 10.1007/s11886-010-0106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams D, Davison J. Chronic kidney disease in pregnancy. BMJ. 2008;336:211–215. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39406.652986.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibai BM. Maternal and uteroplacental hemodynamics for the classification and prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;52:805–806. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.119115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sattar N, Greer IA. Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ. 2002;325:157–160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7356.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamarca BD, Gilbert J, Granger JP. Recent progress toward the understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;51:982–988. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thornburg KL, Jacobson SL, Giraud GD, Morton MJ. Hemodynamic changes in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(00)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke SD, Barrette VF, Bianco J, et al. Spiral arterial remodeling is not essential for normal blood pressure regulation in pregnant mice. Hypertension. 2010;55:729–737. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomei A, Siegert S, Britschgi MR, Luther SA, Swartz MA. Fluid flow regulates stromal cell organization and CCL21 expression in a tissue-engineered lymph node microenvironment. J Immunol. 2009;183:4273–4283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulandavelu S, Qu D, Adamson Sl. Cardiovascular function in mice during normal pregnancy and in the absence of endothelial NO synthase. Hypertension. 2006;47:1175–1182. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000218440.71846.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox B, Kotlyar M, Evangelou AI, et al. Comparative systems biology of human and mouse as a tool to guide the modeling of human placental pathology. Mol Syst Biol. 2009:5. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mu J, Adamson SL. Developmental changes in hemodynamics of uterine artery, utero- and umbilicoplacental, and vitelline circulations in mouse throughout gestation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1421–1428. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00031.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anson-Cartwright L, Dawson K, Holmyard D, Fisher SJ, Lazzarini RA, Cross JC. The glial cells missing-1 protein is essential for branching morphogenesis in the chorioallantoic placenta. Nat Genet. 2000;25:311–314. doi: 10.1038/77076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croy BA, Suzanne DB, Barrette V, et al. Identification of the primary outcomes that result from deficient spiral arterial modification in pregnant mice. Preg Hyper: An Int J Women’s Cardiovas Health. 2011;1:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leno-Duran E, Hatta K, Bianco J, et al. Fetal-placental hypoxia does not result from failure of spiral arterial modification in mice. Placenta. 2010;8:731–737. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Croy BA. Using ultrasonography to define fetal maternal relationships: moving from humans to mice. Comp Med. 2009;59:527–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke SD, Barrette V, Gravel J, et al. Uterine NK cells, spiral artery modification and the regulation of blood pressure during mouse pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:472–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papageorghiou AT, Leslie K. Uterine artery Doppler in the prediction of adverse pregnancy outcome. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:103–109. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32809bd964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh GS, Gudmundsson S. Uterine and umbilical artery Doppler are comparable in predicting perinatal outcome of growth-restricted fetuses. BJOG. 2009;116:424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olofsson P, Laurini RN, Marsal K. A high uterine artery pulsatility index reflects a defective development of placental bed spiral arteries in pregnancies complicated by hypertension and fetal growth retardation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1993;49:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(93)90265-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford LW, Foley JF, Elmore SA. Histology atlas of the developing mouse hepatobiliary system with emphasis on embryonic days 9.5–18. 5. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38:872–906. doi: 10.1177/0192623310374329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coan PM, Angiolini E, Sandovici I, Burton GJ, Constancia M, Fowden AL. Adaptations in placental nutrient transfer capacity to meet fetal growth demands depend on placental size in mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:4567–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Osmond C, Thornburg K, Barker D. Boys live dangerously in the womb. Am J Hum Biol. 2010;22:330–335. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Rosa MJ, Dionisio L, Agriello E, Bouzat C, Esandi M. Alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulates lymphocyte activation. Life Sci. 2009;85:444–49. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatta K, Carter AL, Chen Z, et al. Expression of the vasoactive proteins AT1, AT2, and ANP by pregnancy-induced mouse uterine natural killer cells. Reprod Sci. 2010;18:383–90. doi: 10.1177/1933719110385136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tayade C, Fang Y, Hilchie D, Croy BA. Lymphocyte contributions to altered endometrial angiogenesis during early and midgestation fetal loss. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:877–86. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0507330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, et al. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:132–40. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Kim CJ. Placental bed disorders in the genesis of the great obstetrical syndromes. In: Pijnenborg R, Brosens I, Romero R, editors. Placental bed disorders. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Ma H, Tong C, et al. Overnutrition and maternal obesity in sheep pregnancy alter the JNK-IRS-1 signaling cascades and cardiac function in the fetal heart. FASEB J. 2011;24:2066–76. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-142315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romundstad PR, Magnussen EB, Smith GD, Vatten LJ. Hypertension in pregnancy and later cardiovascular risk: common antecedents? Circulation. 2010;10:579–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.943407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.