Abstract

Purpose: In this study, we used a small field high resolution detector in conjunction with a full field flat panel detector to implement and investigate the dual detector volume-of-interest (VOI) cone beam breast computed tomography (CBCT) technique on a bench-top system. The potential of using this technique to image small calcifications without increasing the overall dose to the breast was demonstrated. Significant reduction of scatter components in the high resolution projection image data of the VOI was also shown.

Methods: With the regular flat panel based CBCT technique, exposures were made at 80 kVp to generate an air kerma of 6 mGys at the isocenter. With the dual detector VOI CBCT technique, a high resolution small field CMOS detector was used to scan a cylindrical VOI (2.5 cm in diameter and height, 4.5 cm off-center) with collimated x-rays at four times of regular exposure level. A flat panel detector was used for full field scan with low x-ray exposures at half of the regular exposure level. The low exposure full field image data were used to fill in the truncated space in the VOI scan data and generate a complete projection image set. The Feldkamp-Davis-Kress (FDK) filtered backprojection algorithm was used to reconstruct high resolution images for the VOI. Two scanning techniques, one breast centered and the other VOI centered, were implemented and investigated. Paraffin cylinders with embedded thin aluminum (Al) wires were imaged and used in conjunction with optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dose measurements to demonstrate the ability of this technique to image small calcifications without increasing the mean glandular dose (MGD).

Results: Using exposures that produce an air kerma of 6 mGys at the isocenter, the regular CBCT technique was able to resolve the cross-sections of Al wires as thin as 254 μm in diameter in the phantom. For the specific VOI studied, by increasing the exposure level by a factor of 4 for the VOI scan and reducing the exposure level by a factor of 2 for the full filed scan, the dual-detector CBCT technique was able to resolve the cross-sections of Al wires as thin as 152 μm in diameter. The CNR evaluated for the entire Al wire cross-section was found to be improved from 5.5 in regular CBCT to 14.4 and 16.8 with the breast centered and VOI centered scanning techniques, respectively. Even inside VOI center, the VOI scan resulted in significant dose saving with the dose reduced by a factor of 1.6 at the VOI center. Dose saving outside the VOI was substantial with the dose reduced by a factor of 7.3 and 7.8 at the breast center for the breast centered and VOI centered scans, respectively, when compared to full field scan at the same exposure level. The differences between the two dual detector techniques in terms of dose saving and scatter reduction were small with VOI scan at 4× exposure level and full field scan at 0.5× exposure level. The MGDs were only 94% of that from the regular CBCT scan.

Conclusions: For the specific VOI studied, the dual detector VOI CBCT technique has the potential to provide high quality images inside the VOI with MGD similar to or even lower than that of full field breast CBCT. It was also found that our results were compromised by the use of inadequate detectors for the VOI scan. An appropriately selected detector would better optimize the image quality improvement that can be achieved with the VOI CBCT technique.

Keywords: dual detector VOI cone beam CT, volume-of-interest, VOI mask, dose saving, scatter reduction, breast imaging

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women after skin cancers.1 In the United States, nearly one in four cancers diagnosed are breast cancers. In 2009, breast cancer death is the second most cancer deaths in women followed by lung cancer.2 Early detection of breast cancer could result in more successful treatment and better survival rate.3 Thus, early detection is essential to surviving breast cancer. Currently, mammography is the single most effective method used in screening and diagnosis. On average, 80%–90% of breast cancers are detected by mammography.2 However, the accuracy and usefulness of mammography is limited by its two-dimensional (2D) nature, which results in the overlapping of soft tissue masses or microcalcifications (MCs) with breast anatomy. This was estimated to contribute to about 15% of unidentified breast cancers with mammography.4, 5

The overlapping problem can best be resolved by using a three-dimensional (3D) x-ray imaging technique which allows the breast anatomy and lesions to be visualized in a true or pseudo 3D manner. 3D imaging techniques, including tomosynthesis,6, 7 conventional computed tomography (CT),8, 9 and flat panel based cone beam cone beam breast computed tomography (CBCT),10, 11 have been proposed and investigated for breast imaging in the past decade. Among them, the pendant geometry CBCT breast imaging techniques have drawn great attention and demonstrated significant improvement in the detection of small lesions. In addition to the high contrast sensitivity, CBCT also has the advantage of nearly isotropic high spatial resolution. This has led to many efforts to develop and investigate breast CBCT techniques.10, 12, 13, 14, 15

Poor MC detection and radiation dose to the breast have been the two major drawbacks in CBCT breast imaging. The detection and visualization of MCs are an important task in the screening and diagnosis of breast cancers, since they have often led to early detection of breast cancers.16 With computer simulation, the minimum detectable size of calcification size has been estimated to be about 175–200 μm for a flat panel-based CBCT system.17, 18 Imaging experiments with an experimental flat panel-based CBCT system have been used to demonstrate a minimum detectable MC size of 250 μm, while smaller MCs were invisible due to limited exposure level and spatial resolution of the detector used.14 Using a CCD detector, we have demonstrated the detection of 150 μm MCs and concluded that the use of a high resolution detector in conjunction with elevated exposure level hence increased signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) could improve the detection of MCs.19 However, it is generally recognized by researchers that the breast dose for CBCT should be kept within the mean glandular dose (MGD) limit for two view mammography.20 This makes it difficult to justify increasing the exposure level as required for imaging smaller MCs. However, once the lesion is detected and localized, it may not be necessary to obtain high quality images of the entire breast in the subsequent procedures such as diagnostic workup or staging. Thus, a pre-selected volume-of-interest (VOI) may be scanned at high exposure level with collimated x-rays to keep the overall dose to the breast at an acceptable level. This technique is referred to as the VOI CBCT technique in this article.

VOI CBCT may be useful in diagnostic workup or staging. However, selection of VOI may require special considerations. In diagnostic workup, a full field CBCT scan may be performed first in replacement of regular mammograms. The VOI may be selected by comparing the original screening mammograms with CBCT images to determine the location of the suspicious lesions. The two view mammograms should provide clues on the location of the lesions in relation to the breast anatomy (distorted by compression). Corresponding locations and dimensions may be determined in the CBCT images using their spatial relationship relative to the breast anatomy. Accurate registration may not be necessary but the CBCT images may be deformed to produce a “compressed view” for easier comparison with the two view mammograms. A low exposure full field scan as described in this study is unnecessary because a full field scan is already available. When staging breast cancer, the lesion should have been identified along with its location and dimensions in diagnostic workup. A full field scan or VOI CBCT may have been performed and provide adequate 3D breast images for selecting the VOI. Depending on whether the breast can be positioned in a reproducible way, a separate low exposure full field scan may need to be performed to localize the VOI and to provide full field projection images for use with the VOI only projection images for reconstruction. The VOI CBCT technique may be especially useful in imaging MCs which requires a high resolution detector and higher exposure level. However, even for soft tissue masses, the VOI CBCT technique may help provide clearer view of the tumor margins for monitoring the growth or recession of the tumor or for surgical planning.

However, collimated scan of the VOI only lead to data truncation in the projection images and result in image artifacts.21, 22 To resolve the truncation problem, Azevedo et al. first proposed a method based on combining images from a full field scan with those from the ROI scan.23 Later, Guan et al. introduced the concept of combining truncated data with full field data for iterative reconstruction in 2000.24 Chityala et al. implemented and demonstrated the technique to combine truncated projection data with full field data to obtain a complete set of projection data for reconstruction using the FDK algorithm in 2004.25 A similar technique was also implemented and investigated on a C-arm flat-panel based CBCT system by Kolditz et al. later.26 In 2008, Patel et al. modified this technique by using a CCD detector to obtain high resolution projection images of the VOI to provide better resolution to image small details within the VOI in neuroradiological imaging applications.27 And Maass et al. further developed two methods to improve the reconstructed image quality for this type of geometry.28 For CBCT breast imaging, we have proposed and investigated a similar technique, referred to as the dual detector VOI CBCT technique, to improve the visibility of MCs in a pre-selected VOI while keeping the average radiation dose to the breast at an acceptable level.29, 30 With this technique, the VOI is scanned with a small field high resolution detector at high exposure level while the entire breast is scanned with a full field flat panel detector at a reduced exposure level. These two scans are referred to as the VOI scan and the full field scan, respectively, in this paper. The dual detector VOI CBCT technique was first demonstrated by Chen et al. using the ray tracing image simulation techniques and investigated for its dose saving and scatter reduction advantages using the Monte Carlo method.29 The dual detector VOI CBCT technique was also demonstrated with an a-Si∕a-Se flat panel detector based bench top experimental system.30 The benefits of the dual detector VOI CBCT technique for dose saving and scatter reduction were experimentally measured and demonstrated using the breast centered scanning technique by Lai et al. in 2009.31, 32

In this paper, we describe and discuss the implementation of the dual detector VOI CBCT technique with breast centered and VOI centered scanning techniques on a bench top experimental CBCT system for a cylindrical VOI (2.5 cm in diameter and height, 4.5 cm off-center). Images of Al wires are presented to demonstrate the ability of the technique to image small calcifications. Scatter-to-primary ratio (SPR) measurements are presented to demonstrate the benefit of the technique for scatter reduction. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dose measurements and Monte Carlo estimation of the MGDs are presented to demonstrate the potential benefit of dose saving which may help enable the imaging of small calcifications of a selected VOI without increasing the integral dose to the breast.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bench top system

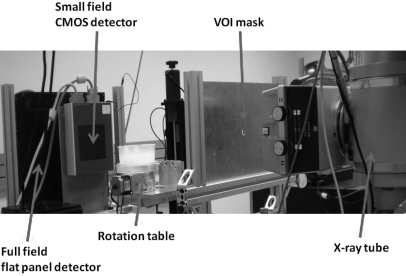

A bench-top experimental CBCT system was configured to demonstrate the dual-detector VOI CBCT technique. As shown in Fig. 1, the system consisted of an x-ray tube, a full field flat panel detector, a small field CMOS detector, and a step motor-driven rotating table. The x-ray tube (G-1593∕B180, Varian Medical System, Salt Lake City, UT) was powered by a high power x-ray generator (CPI Indico 100SP, Communications & Power Industries, Ontario, Canada) and operated with a nominal focal spot size of 0.3 mm. The breast phantom was placed on the rotating table (B4872TS, Velmex Inc., Bloomfield, NY) for full 360 degree rotation during the scan. The full field flat panel detector (FPD14, Anrad Corporation, Saint-Laurent, Canada) is a 12-bit amorphous selenium (a-Se)-based direct conversion flat panel detector capable of acquiring 7.5 2304 × 2304 images per second with a pixel size of 150 μm to cover an active image area of 33.6 × 34.2 cm2. Due to limited time of availability, two different small field CMOS detectors (C7921CA-09 or C9312SK-06, Hamamatsu Corporation, Hamamatsu City, Japan), both on loan from the manufacture, were used for the high resolution VOI scan in this study. Both detectors provide 12-bit image data with a pixel size of 50 μm. The C7921CA-09 CMOS detector, using a CsI scintillator, acquires images as 1056 × 1056 matrices to cover an active image area of 52.8 × 52.8 mm2. The C9312SK-06 CMOS detector, using a GdOS screen as the scintillator, acquires images as 2496 × 2304 matrices to cover an active image area of 124.8 × 115.2 mm2. The characteristics of the detectors, acquisition techniques, and imaging geometries are listed in Table Table I.. More detailed specifications and characteristics on the Anrad detector were previously reported on.33 Those for the two Hamamatsu detectors may be found on the manufacturer’s specifications.34, 35 To ensure that image data were not limited by the system noises, image signals and noise levels were measured for each of the three detectors for a large range of exposures. The noise variances were then plotted as a function of the exposure level to verify and ensure that noise properties followed Poisson statistics and the image quality was not limited by the system noises for the exposure levels studied.

Figure 1.

Experimental stationary gantry CBCT system with Anrad flat panel detector and Hamamatsu CMOS detector.

Table 1.

Characteristics of detectors and imaging geometry.

| Parameters | Flat panel detector | CMOS detector | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Anrad FPD14 | Hamamatsu C7921CA | Hamamatsu C9312SK |

| Detector type | a-Se | CsI | GdOS |

| Maximum pixel number | 2304 × 2304 | 1056 × 1056 | 2496 × 2304 |

| Data depth | 12 bit | 12 bit | 12 bit |

| Intrinsic pixel size | 150 μm | 50 μm | 50 μm |

| Active image area | 33.6 × 34.2 cm2 | 52.8 × 52.8 mm2 | 124.8 × 115.2 mm2 |

| Frame rate at full resolution | 7.5 fps | 4 fps | 8 fps |

| Source-to object distance | 88 cm | 88 cm | 88 cm |

| Source-to-detector distance | 135 cm | 110 cm | 110 cm |

| Geometric magnification at iso-center | 1.53 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Voxel size | 98 μm | 40 μm | 40 μm |

| MTF at 3.3 lp∕mm | 35% | 36% | 43% |

| MTF at 10 lp∕mm | NA | 3.5% | 4% |

| DQE at 0.5 lp∕mm | 58.5% | NA | NA |

| Dark current noise (μR) | 0.6 | 64 | 78 |

Phantoms

Figure 2a illustrates the construction of the breast phantom and the Al wire inserts used in this study. A 13 cm diameter and 4.0 cm high paraffin cylinder was used to simulate an uncompressed breast. Two Al wire inserts were constructed as 1.5 cm diameter, 6 cm high paraffin rods, with 8 thin aluminum (Al) wires (76, 102, 127, 152, 178, 203, 229, and 254 μm in diameter) embedded to test the ability of the dual detector VOI CBCT techniques to image small calcifications. The wires were oriented in parallel to and evenly spaced at 0.5 cm from the central axis of the inserts. Two 1.5 cm diameter holes, one at the center and the other at 4.5 cm from the central axis, were opened in the breast phantom to hold the Al wire inserts. Paraffin is similar to adipose tissue in x-ray attenuation and density (0.2092 cm2∕g and 0.93 g∕cm3 for paraffin, 0.2123 cm2∕g and 0.92 g∕cm3 for adipose tissue at 50 keV).36, 37 It was used as the phantom material because it is easy to manipulate in fabricating both the breast phantom and the wire inserts. Figure 2b shows a photo of the breast phantom and an Al wire insert on the right side. And, Fig. 2c shows a reconstructed Al wire phantom image with location of Al wire labeled.

Figure 2.

(a) Layout and (b) picture of breast phantom and Al wire phantom. (c) Reconstructed Al wire phantom image. The wire diameters were 76, 102, 127, 152, 178, 203, 229, and 254 μm clockwise from 4 o’clock position.

Image acquisition

The dual detector VOI CBCT technique requires the use of a VOI scan to acquire high quality projection images of the VOI and a full field scan to acquire full field images of the entire breast. For both scans, the x-ray source-to-isocenter distance (SCD) was set to be 88 cm. For the VOI scan, one of the two CMOS detectors was used with the source-to-image distance (SID) set at 110 cm resulting in a magnification factor of 1.25. For the full field scan, the Anrad FP detector was used with the SID set at 135 cm resulting in a magnification factor 1.53. The use of different SIDs allowed us to achieve different geometric magnification factors to match the focal spot blurring effect with the detector blurring effect at the isocenter for each different detector. This not only led to optimal overall spatial resolution but also allowed the CMOS detector to be positioned in front of the flat panel detector for the VOI scan. A VOI mask, consisting of a 3 mm thick lead plate with a 1.5 cm wide square opening at the center, was used to generate a collimated x-ray beam to scan the VOI while blocking x-ray exposures to regions outside the VOI in the projection views. The VOI mask was placed at 52.8 cm from the focal spot with the upper edge of the square opening centered with and positioned right underneath the imaging axis which is defined as the straight line originating from the focal spot and intersecting the rotation axis perpendicularly at the isocenter. This led to coverage of a 2.5 × 2.5 cm2 field of view at the isocenter by the collimated x-ray beam and defined a cylindrical VOI 2.5 cm in diameter and height, which occupied 2.3% of the breast volume. The dimension of the VOI used here is able to cover a lesion (MC or soft tissue) of ∼1.5 cm in diameter with 0.5 cm clearance on all sides.

Three hundred images were acquired with 30 ms pulsed x-ray exposures at 80 kVp with a focal spot size of 0.3 mm. The images were acquired at a rate of 3.75 fps or every 267 ms. Thus, the 30 ms pulsed x-ray exposures effectively reduced motion blurring during image acquisition. A regular 80 kVp radiographic x-ray spectrum with a mean photon energy of 47 keV and a half value layer of 4.08 mm was used without additional filtration. For regular flat panel based CBCT, the images were acquired with a total exposure that led to an isocenter air kerma of 6 mGys with a Lucite phantom of the same dimensions. This exposure level is referred to as the 1 × exposure level in this manuscript as it would incur a MGD of 3.4 mGys well below the 6 mGy MGD limit for two view mammograms. For dual detector VOI CBCT, the VOI scans were performed at a higher exposure level leading to an isocenter air kerma of 24 mGys or 4 × exposure level. The full field scans, required only to fill in the truncated space outside the VOI, were performed at a lower exposure level, leading to a measured isocenter air kerma of 3 mGys or 0.5 × exposure level.

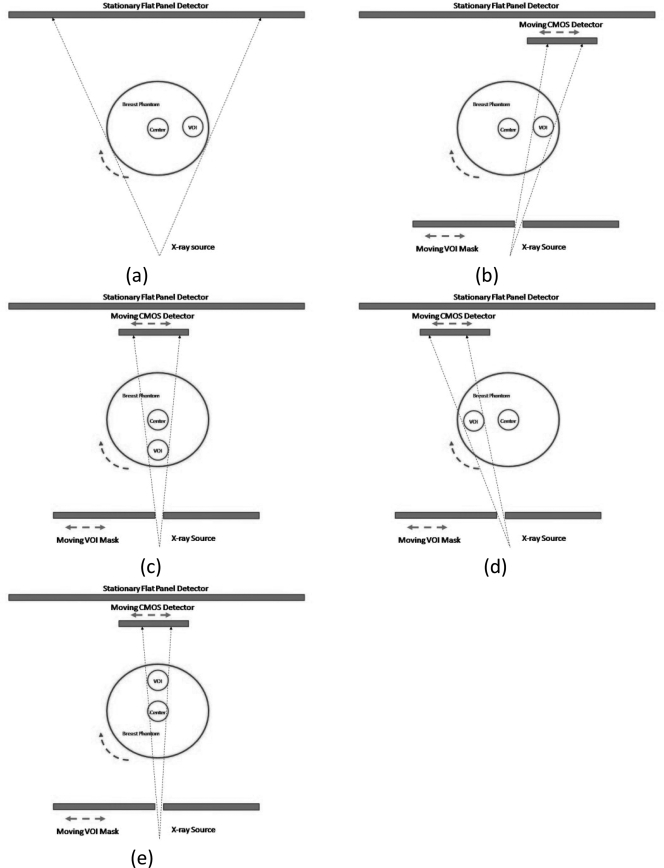

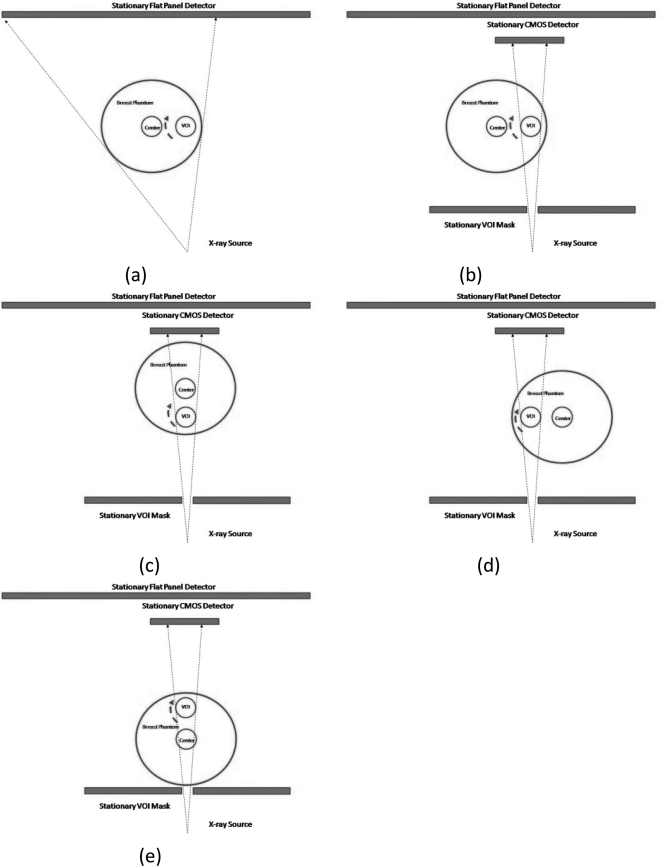

A breast centered approach (Fig. 3) and a VOI centered approach (Fig. 4) were used to implement the VOI scan on our bench-top experimental CBCT system. With the breast centered approach, the breast phantom is centered with the rotating axis. During the scan, the VOI mask and the CMOS detector are moved synchronously to track and image the VOI at various view angles [Figs. 3b–3e]. With the VOI centered technique, the VOI instead of the breast is centered with the rotating axis. Both the VOI mask and the CMOS detector are centered with respect to the rotating axis as well and remain stationary during the scan [Figs. 4b–4e]. It should be noted that with a patient imaging system, the CMOS detector, the VOI mask and the x-ray source would rotate around the center of the breast or the VOI with the breast centered or the VOI centered approach, respectively. However, the VOI mask and the detector would move laterally on the rotating gantry to track and image the VOI with the breast centered approach while remaining stationary with the VOI centered approach. To simplify image processing, the full field scans were performed with the same phantom position as the VOI scans. The C7921CA-09 was used in breast centered approach and C9312SK-06 was used in VOI centered approach.

Figure 3.

Schematic drawings of the breast centered technique. (a) Low resolution scan of entire breast phantom. (b)–(e) High resolution scans of VOI in synchronous order.

Figure 4.

Schematic drawings of the VOI centered technique. (a) Low resolution scan of entire breast phantom. (b)–(e) High resolution scans of VOI in synchronous order.

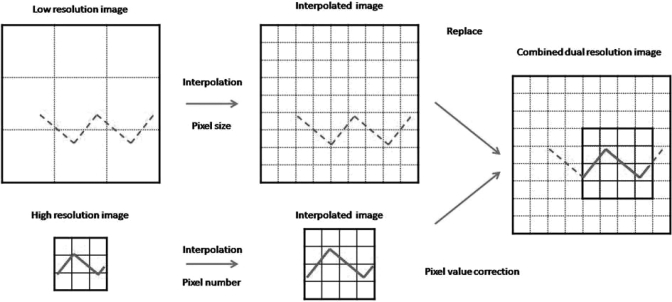

Combining images from full field and VOI scans

Due to the use of collimated x-rays to only cover the VOI, the VOI scan data are truncated outside the VOI. To avoid the truncation artifacts, projection data from the low exposure full field scan were used to fill in the space outside the VOI to form a complete projection image set for reconstruction. Because two different detectors, with different pixel sizes and at different locations, were used for the full field and VOI scans, the two images were registered and processed to compensate for differences in the pixel size and geometric magnification prior to combination. A schematic diagram for combining the two projection images is shown in Fig. 5. First, the 150 μm full field images acquired with the flat panel detector were converted into larger (by a factor of 3 in both horizontal and vertical directions) sub-sampled (every 50 μm as with the VOI scan images) matrices using the bi-linear interpolation method. Second, the VOI scan images were magnified to match the geometric magnification of the full field images. The magnified images were then sub-sampled and converted into 50 μm images again. Following the processing, the new image matrix size of the processed VOI scan images became, Nxnew × Nynew, where Nxnew or Nynew may be computed as follows:

| (1) |

where SIDFP and SIDCMOS are the SIDs for the flat panel detector and the CMOS detector, respectively.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram for how to combine dual detector image from experimental images.

The two re-sampled and registered projection image sets were combined together by replacing the low exposure data from the full field flat panel images with the high exposure VOI scan image data in the VOI region. However, the two sets of images had different signal levels because they were generated with different detectors at different exposure levels. Thus, they were normalized to the same signal level prior to combination to ensure consistent attenuation measurement and smooth transition of the pixel values across the boundary of the VOI. This was done by rescaling the VOI scan image signals so that the mean values over a selected region of interest inside the VOI were the same as those in the full field images. The normalized pixel values (Inew) in the VOI scan images were calculated as follows:

| (2) |

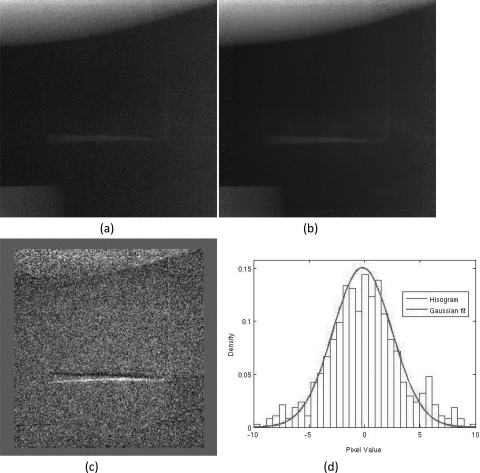

where ICMOS is the pixel value in the VOI scan image while ĪFP and ĪCMOS are the mean pixel values over the same region of interest in the full field scan image and the VOI scan image, respectively. Figures 6a–6c show an example of the full field scan image, VOI scan image, and combined image, respectively. Figure 6c shows that signal transition across the VOI boundaries was smooth and continuous. The accuracy of image registration and normalization can also be assessed by subtracting the combined image from the corresponding full field image. Figures 7a, 7b show a subtracted image and its histogram, respectively. The image appears to contain little structure [Fig. 7a]. The minor artifices along the high contrast edges of the VOI in the subtracted image were likely caused by the drastic change of the scatter distribution in the collimated VOI scan image. The histogram of the subtracted image fits well to a Gaussian distribution [Fig. 7b], indicating the white noise signature and lack of structures in the subtracted image.

Figure 6.

(a) Full field projection image acquired with flat panel detector, (b) high resolution image of the VOI acquired with a CMOS detector, and (c) the combined dual detector image following spatial registration and normalization of pixel values.

Figure 7.

Magnified section of the VOI from (a) interpolated low resolution image, (b) combined dual detector image, and (c) the subtracted image between (a) and (b). The histogram of the subtracted image is shown in (d).

Image reconstruction

Three hundred projection images were acquired over 360° rotation for both full field and VOI scans. Feldkamp’s backprojection algorithm was used for image reconstruction. A ramp filter was used to optimize the spatial resolution. Dual detector VOI CBCT images were reconstructed with the combined projection images with slice thickness of 40 μm. Regular CBCT images were reconstructed with the full field scan images with slice thickness of 98 μm for comparison. Because the regular CBCT images have a slice thickness of 98 μm versus 40 μm for the VOI CBCT images, the latter were averaged over three consecutive slices for comparison.

Contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) measurement

One advantage of dual detector VOI CBCT is the ability to obtain high quality images of the VOI with the same or even reduced overall dose over regular CBCT technique. To assess and compare the image quality, the CNRs in the reconstructed images were computed and used to evaluate and compare the image quality. The 2D signal profile of the thickest wire (254 μm diameter) was located and fitted with a 2D Gaussian function. Then the CNRs were computed as the ratio of the mean difference signal between the thickest wire and the background region adjacent to the wire to the noise level, computed as the standard deviation of image data in the background. Since the measurement of contrast signals and noise levels were subjected to substantial fluctuations due to high image noise levels, they were averaged over 18 slices prior to computing the CNRs to minimize potential errors due to the fluctuations. The use of and positioning Al wires in perpendicular to the image plane have made it possible to do so because the cross-section of the wires remained the same in size and location.

Dose measurement

To estimate the isocenter doses for the dual detector VOI CBCT imaging procedure, OSL dosimeters (microStar, Landauer, Inc., Glenwood, IL) were placed underneath the Al wire inserts to measure the doses there. These dosimeters were placed at selected locations inside the phantom. During the scan, they absorbed and stored part of the x-ray energy. Following the scan, they were stimulated by LED light and released the stored energy as light signals for read out with a specially designed reader.38, 39 These signals were then converted into doses through calibration against ion chamber measurements of free air kerma.

Monte Carlo package DOSXYZnrc was used to estimate the MGD to the breast and the VOI.40, 41 The energy deposited by the x-ray photons was tallied for each voxel (1 × 1 × 1 mm3) in the phantom to estimate the glandular tissue dose on a voxel-by-voxel basis. The doses were then averaged over the entire phantom volume and VOI to compute the MGD and the ratios of the MGD to selected point doses. The ratios were then used to convert the OSL point dose measurements into mean glandular tissue doses.

Scatter measurement

Scatter components in the projection images were measured using the slot collimation method described by Lai et al.32 A slot collimator made of a 4 mm thick lead plate with a variable width slot opening was placed between the phantom and x-ray tube to generate a narrow x-ray fan beam. Image signals in the fan beam area consist of mostly primary signals and some scattered x-rays. The slot width was varied by moving one edge while keeping the other edge stationary. The signal profile in the opening 0.9 mm away from the stationary edge was measured for each different slot width. As the slot width decreased from 12.8 to 3.8 mm in 1.8 mm steps, the primary components in the measured signals remained unchanged while the scatter components decreased and approached zero. By extrapolating the total image signals to zero slot width, the primary signal values were estimated near the stationary edge of the slot. 20 images were acquired with identical x-ray techniques and averaged to reduce the noise fluctuations for estimation of primary signals. Both the scatter signals, computed by subtracting the primary signals from the total signals, and the scatter-to-primary ratios (SPRs) were estimated for each different scanning technique for comparison.

RESULTS

Reconstructed CBCT images

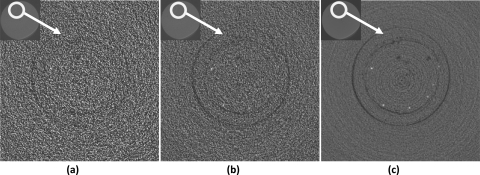

Figure 8 shows the reconstructed Al wire images obtained with the regular CBCT technique at 0.5× , 1× , and 9× exposure levels. At 0.5× exposure level, none of the Al wires were visible. At 1× exposure level, Al wire with a diameter of 254 μm was visible. At 9× exposure level, the minimum resolvable wire diameter decreased to 127 μm (sixth wire).

Figure 8.

Regular CBCT images of Al wires obtained at (a) 0.5×, (b) 1×, and (c) 9× exposure levels.

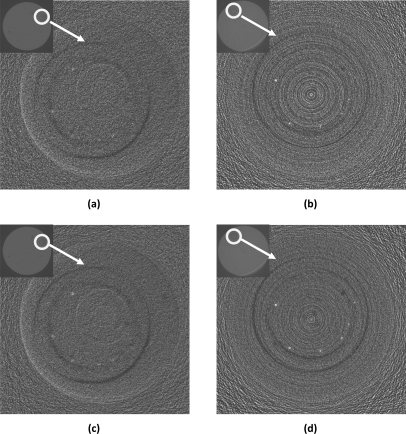

Figure 9 shows the reconstructed Al wire images obtained with dual detector VOI CBCT techniques. Since the slice thickness and exposure level were different between the regular and dual detector VOI CBCT techniques, the photo fluence over VOI were different. For fair comparison, the slice images obtained with the VOI CBCT technique have been averaged over three consecutive slices to equalize the photon fluence ((98 μm∕40 μm) × (9× ∕8×) ∼ 3) between the two techniques. Figures 9a, 9b show the reconstructed Al wire images obtained with dual detector VOI CBCT techniques with breast centered VOI scan and VOI centered VOI scan, respectively. With either scanning technique, the exposure levels were 0.5× outside the VOI and 4× inside the VOI. The minimum resolvable wire diameter was 152 μm with both techniques (fifth wire). Figures 9c, 9d show the similar dual detector VOI CBCT images with 0.5 × exposure level outside the VOI and 8 × exposure levels inside the VOI. The minimum resolvable wire diameter was improved to 127 μm with VOI centered technique (sixth wire).

Figure 9.

Dual detector VOI CBCT images of Al wires obtained with (a) breast centered technique with VOI exposure at 4×, (b) VOI centered technique with VOI exposure at 4×, (c) breast centered technique with VOI exposure at 8×, and (d) VOI centered technique with VOI exposure at 8×. Those images have been averaged over three consecutive slices to equalize the photon fluence.

The quality of the dual detector VOI CBCT images was clearly improved over that of the regular CBCT image at 1× exposure level. The Al wires appeared clearer and smaller wires were visible with the minimum resolvable wire diameter decreased from 254 to 152 μm.

Table Table II. shows the measured contrasts, noises and CNRs in reconstructed images acquired with three different CBCT techniques. The voxel noise levels measured the level of fluctuations for the voxel signals. The normalized noise levels measured the level of fluctuations for signals binned into same sized voxels as in the regular CBCT. Since the voxel size in the dual-detector VOI CBCT images was about three times smaller than that in the regular CBCT images (40 μm versus 100 μm), the wire cross-section covered 3 × 3 = 9 times more voxels in the dual-detector VOI CBCT image than in the regular CBCT image. Thus, the normalized noise levels were computed by dividing the noise level by 3 (square root of 9) to account for the noise smoothing effect of averaging image signals over nine times more voxels. Notice that the contrast signals were already computed with signals averaged over the wire cross-sections. Thus, the normalized CNRs were estimated by multiplying the voxel CNRs by 3 to account for the reduction of noise level.

Table 2.

Contrast, noise levels, CNRs, and estimated Al wire sizes in reconstructed images from regular CBCT scanned at 1 × exposure and dual detector VOI CBCT. The normalized noise levels and CNRs were obtained for differences of the voxel size and the number of voxels covered by the Al wire cross-sections.

| Dual detector CBCT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular CBCT (1×) | Breast centered | VOI centered | |

| Contrast (×103)(HUs) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 |

| Voxel noise level(HUs) | 274 ± 8 | 281 ± 3 | 333 ± 12 |

| Normalized noise level(HUs) | 274 ± 8 | 94 ± 1 | 111 ± 4 |

| Voxel CNR | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.7 |

| Normalized CNR | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 16.2 ± 2 | 22.5 ± 3 |

| Size (μm) | 236 | 281 | 196 |

Dose measurements

Table Table III. shows glandular doses measured at various locations and mean glandular doses from Monte Carlo estimation with the same 1× x-ray output for the three different CBCT techniques. From this table, doses at the VOI center (inside the VOI) were reduced by a factor of 1.6 with both breast and VOI centered scans. Doses at the breast center (outside the VOI) were reduced by a factor of 7.3 or 7.8 for breast or VOI centered scans, respectively.

Table 3.

Measured point glandular doses at various locations and mean glandular doses estimated with help from Monte Carlo simulation for different techniques with the same 1× x-ray output.

| Technique | Point Dose(mGy) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | VOI mask | MGD(mGy) | Breast center | VOI center |

| Breast-centered | No | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

| Yes | 0.4 | 0.4 | 2.3 | |

| VOI-centered | No | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| Yes | 0.4 | 0.4 | 2.3 | |

Using the point dose-to-MGD ratios from Monte Carlo simulation, the mean glandular dose was estimated to be 3.4 mGys for regular CBCT at 1× exposure level, 3.2 mGys for dual detector VOI CBCT with 0.5× exposure outside the VOI and 4× exposure inside the VOI, regardless of breast centered or VOI centered scans.

Thus, with either scanning technique, the MGD for the above configured dual detector VOI CBCT technique was actually lower (94%) than that for the regular CBCT technique.

Scatter measurements

For regular CBCT, the SPR averaged over 100 pixels in the VOI was 0.38 (±0.06) for breast-centered scan and 0.36 ± (0.06) for VOI centered scan. For dual detector VOI CBCT, the average SPR was reduced to 0.05 (±0.03) by a factor of 7.6 with breast centered scan and to 0.04 (±0.06) by a factor of 9.0 with VOI centered scan. This is in good agreement with previously reported values when VOI was fixed at breast center.33

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that the dual detector VOI CBCT technique allowed a VOI (2.5 cm in diameter and height, 4.5 cm off-center) to be imaged with enhanced image quality while maintaining the MGD at the same or even a lower level. The improvement was demonstrated as better visibility of thin Al wires in Figs. 9a, 9b over those in Fig. 8b. The images in Figs. 89 appear quite noisy. One cause for the noisy images is the use of a ramp filter to reconstruct the images to avoid image blurring. Another cause is the magnification of the VOI region for display (original size highlighted in red in the inserts). The higher noise levels in Figs. 9a, 9b also reflect the inadequacy of exposure levels for imaging very small objects. The two black rings in all images originated from air gap between the calcification insert and the breast phantom or the air bubbles introduced when paraffin was cooled layer by layer during fabrication. The multiple ring artifacts in Figs. 9b, 9d were typical for CBCT with non-uniform detector gain or defects in the region around the center of rotation. These artifacts were also present in the images obtained with breast centered scans but not present in the VOI region.

The image quality improvement was also shown as reduced noise levels and improved CNRs. Our dose and scatter measurements show that the use of collimated x-rays in acquiring the high resolution projection images of the VOI resulted in substantial dose saving inside the VOI and even greater dose saving outside the VOI when compared to full field CBCT at the same exposure level. Similarly, the SPR was also substantially reduced inside the VOI. However, a full field scan is still needed to provide data outside the VOI to form a complete projection data set for image reconstruction to avoid truncation artifacts. This scan can be a previous scan used to select the VOI or a new one performed at an exposure level as low as 0.1× to keep the overall MGD down. The improvement originated mainly from scanning the VOI at a higher exposure level (e.g., 4× or 8×) to enhance the image quality inside the VOI as shown in Figs. 9d, 9d. The combination of the two sets of images, however, results in sudden change of the scatter component across the VOI boundaries and ring like artifacts along the boundary of the VOI in the reconstructed images. It should be noted that the degree of dose saving and scatter reduction are expected to depend on the size of the VOI and to a less extent on the location of the VOI. Generally speaking, the larger the VOI the less the dose would be saved and the scatter reduced.

In breast imaging, the more relevant and challenging task is to detect and visualize MCs in dense tissue. In our demonstration, Al wires, instead of calcifications were used to demonstrate the ability of dual detector VOI CBCT to image small MCs. This was done because Al wires are easy to manipulate and use in fabricating the phantoms. For both the breast phantom and Al wire inserts, paraffin, which is similar to the adipose tissue in x r-ay attenuation, was used as the background material. Compared to dense tissue, this would make it easier to detect and visualize the Al wires as paraffin or adipose tissue has lower linear attenuation coefficients (LACs) and would help increase the contrast of the Al wires. However, the aluminum, with LACs lower than those of calcifications, tended to decrease the image contrast. Combining these two opposite effects, the contrast of aluminum wires in the adipose tissue is probably similar to that of MCs in the dense tissue.

The VOI CBCT image in Fig. 9d, obtained with 8× exposures and averaged over 3 consecutive slices, compared well with the regular CBCT image in Fig. 8c, obtained with 9× exposure level, with 6 wires (as thin as 127 μm in diameter) clearly resolved in both images. The VOI CBCT image in Fig. 9b, obtained at 4× exposure level, could almost resolve 6 wires but the higher noise level made the 127 μm diameter wire only faintly visible. The VOI CBCT images obtained with the breast centered scan [Figs. 9a, 9c] could clearly resolve only five wires with the 127 μm diameter wire only faintly visible. In addition, all wires appeared blurrier and lower in contrast when compared to those obtained with the VOI centered scan [Figs. 9b, 9d]. This may be due to the need to process each VOI scan image differently to correct for the differences in magnification and position for each projection view. The two CMOS detectors used in this study were not optimal. Although they have higher MTFs than the Anrad detector, they have poorer quantum detection efficiencies and sensitivity. This may explain why the image in Fig. 9d appeared to have higher noise level than that in Fig. 8c. Switching to a better detector for VOI scan would reduce the noise level and improve the quality of the reconstructed images. The two black rings in the VOI CBCT images shown originated from the air gaps between the calcification insert and the breast phantom or the air bubbles introduced when paraffin was cooled layer by layer during fabrication. The multiple ring artifacts in Figs. 9b, 9d were typical for CBCT with non-uniform detector gain, defects or noise structures in the region around the center of rotation. These artifacts were also present in the images obtained with breast centered scans but not present in the VOI region. These ring artifacts may be an indication that these detectors were inadequate for use in VOI CBCT and they may be significantly reduced when a better detector is used for the VOI scan.

Table Table II. shows that the contrast signal was higher with the VOI centered dual detector image. Those for the regular and breast centered dual detector images assumed the same lower value. The lower contrast signal for the regular image was probably due to the partial pixel effect as the pixel size of the Anrad detector was 150 μm versus 50 μm for the two Hamamatsu detectors. The lower contrast signal for the breast centered dual detector image was probably due to blurring from the motion of the VOI in breast centered scan. Similarly, the voxel noise level and the voxel CNR were higher with the VOI centered dual detector image. Those for the regular and breast centered dual detector images assumed similar lower value. The lower noise level for the regular image was probably due to the detection of more photons into larger pixels. Although averaging the dual-detector images over three consecutive slices helped reduce the voxel noise level, the effect is equivalent to 3× binning in the vertical direction but the Anrad detector still has the advantage of a horizontally wider pixel for image acquisition. The noise level for the breast centered dual detector image should be higher as well. It lower value was probably due to the blurring effect associated with the processing necessary for correcting for the magnification difference and registration on a view-by-view basis. After normalizing for the voxel size difference, the noise levels for the two dual detector images became substantially lower and the CNRs substantially higher though the CNR for the VOI centered dual detector image was significantly higher than that for the breast centered image. This mirrors the differences in image quality between the regular, breast centered and VOI centered dual detector images [Figs. 8b, 9a, and 9b]. The Al wire diameter was estimated to be 236, 281, and 196 μm from in the regular, breast centered, and VOI centered dual detector images, respectively. The smaller estimate from the VOI centered dual detector image mirrors the sharp appearance of the image and may be related to the smaller pixel size of the detector used. The larger estimate for the breast centered dual detector image mirrors the fact that the image was subjected to serious blurring during the image correction and registration process.

One issue regarding the implementation of dual detector VOI CBCT is whether the scan should be breast or the VOI centered. It was found that both techniques resulted in substantial dose saving and scatter reduction. The differences between these two techniques in dose saving and scatter reduction were slight and insignificant. Thus, the choice of the technique may be determined by image quality and practical considerations. Each of the two scanning techniques has its own advantages and disadvantages. With either scanning technique, the full field flat panel detector may be kept stationary as long as its field of view can accommodate off-center scans as was the case in our study. The implementation of the breast centered approach is more complex as both VOI mask and the small field high resolution detector need to be moved synchronously to track and image the VOI. Thus the position and magnification of the VOI varies with the projection view. As the result, each VOI scan image needs to be separately corrected for magnification and registered with the full field scan image prior to synthesis of a complete projection image. Because this process may be subjected to different errors for different views, this may lead to some blurring of the reconstructed images as demonstrated by the images in Figs. 9a, 9c. With the VOI centered approach, the breast may need to be repositioned, along with the patient, by 0–5 cm, depending on how much the VOI is off-center and how big it is. However, the position and magnification of the VOI stay the same throughout the scan. Thus, all VOI scan images are corrected and registered in the same way for all projection views introducing little blurring in the reconstructed images. This approach requires the use of a larger detector to completely cover the entire breast when the VOI is off the breast center. This also results in larger projection images to be processed for reconstruction thus requiring more computing resources and efforts. In our experiment, the VOI centered scan resulted in projection images whose horizontal coverage increased by a factor of 2.5 as those with the breast centered approach. However, since only the VOI is of interest, regions outside the VOI need not to be reconstructed thus lessening the computing efforts.

This study has been performed with a bench-top experimental CBCT system, which only allows phantoms or breast specimens to be scanned. A patient system is currently being assembled for patient study. The main difference between the patient system and the bench-top system is that the patient and the breast must be kept stationary while the x-ray source-detector gantry rotates around the breast. We have adopted a commonly adopted design with which the patient lie on the table with one breast protruding downward through an opening while the x-ray source and detector gantry rotates around the breast in the tight space underneath the table. This has led to the use of a source-to-isocenter distance and SIDs longer than those used in this study. However, similar geometric magnification factors were used to minimize the overall image blurring. With the exposure factors adjusted to result in the same dose values, we expect that the trends observed in this study would apply to the patient system as well.

The degree of image quality improvement depends very much on the quality and characteristics of the high resolution detector used for the VOI scan. We have verified the linear relationship between the noise variance and the detector exposure. The detector exposure with the heaviest attenuation was estimated to be 0.2 mR and 0.1 mR for the Anrad detector at the 1× and 0.5× exposure levels, respectively. That for the CMOS detectors was estimated to be 1.25 mR. Based on our measurements and published information, these exposure levels were well above the instrumentation noise level. From manufacturer’s specifications or published data, the dark current noise level corresponds to 78 μR for C9312, 64 μR for C7921, and 0.6 μR for Anrad FPD14. The SNR in the thickest part of the phantom was measured to be 36 and 22 for C7921 and C9312 at the 4× exposure level. The SNR was measured to be 20 for the Anrad detector at 1× exposure level. The dark current noise levels for the CMOS detectors are rather high but still well below the lowest detector exposure (in the thickest part of the phantom) in the VOI scan. They might have affected the noise measurements in the Table Table II. but not in a significant way. Despite these findings, the CMOS detectors used in this study were obviously sub-optimal or even inadequate. Their sensitivity, x-ray absorption ratio, and framing rate were all on the low side. To apply this technique to patient imaging, it would be desirable to use a detector with improved ratings for these characteristics. Efforts to explore the use of an alternate detector to implement the VOI CBCT technique for patient imaging are underway.

CONCLUSIONS

We have successfully implemented the dual detector VOI CBCT technique on a bench-top experimental CBCT system using both the breast centered and VOI centered scanning techniques. We have demonstrated the use of the dual detector VOI CBCT technique to image a breast phantom embedded with Al wires of various diameters. For the specific VOI studied (2.5 cm in diameter and height, 4.5 cm off-center), we have shown that with 4× exposures for the VOI scan and 0.5× exposures for the full field scan, the dual detector VOI CBCT technique can potentially be used to image smaller details (152 μm wide Al wires) in a pre-selected VOI with MGD of only 94% of that for the regular full field CBCT at 1× exposure level. It was also found that our results had been compromised by the use of inadequate detectors for the VOI scan. An appropriately selected detector would better optimize the image quality improvement that can be achieved with the VOI CBCT technique.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants CA 104759, CA 13852, and CA 124585 from NIH-NCI, a grant EB00117 from NIH-NIBIB, and a subcontract from NIST-ATP.

References

- American Cancer Society, “Cancer Facts & Figures (2010),” (2010).

- American Cancer Society, “Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2009-2010,” (2010).

- Berry D. A., Cronin K. A., Plevritis S. K., Fryback D. G., Clarke L., Zelen M., Mandelblatt J. S., Yakovlev A. Y., Habbema J. D. F., Feuer E. J., “Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1784–1792 (2005). 10.1056/NEJMoa050518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh P. T., Jarolimek A. M., and Daye S., “The false-negative mammogram,” Radiographics 18, 1137–1154 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin J. M., D’Orsi C. J., Hendrick R. E., Moss L. J., Isaacs P. K., Karellas A., and Cutter G. R., “Clinical comparison of full-field digital mammography and screen-film mammography for detection of breast cancer,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 179, 671–677 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J. T.DobbinsIII and Godfrey D. J., “Digital x-ray tomosynthesis: current state of the art and clinical potential,” Phys. Med. Biol. 48, R65-106 (2003). 10.1088/0031-9155/48/19/R01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Stewart A., Stanton M., McCauley T., Phillips W., Kopans D. B., Moore R. H., Eberhard J. W., Opsahl-Ong B., Niklason L., and Williams M. B., “Tomographic mammography using a limited number of low-dose cone-beam projection images,” Med. Phys. 30, 365–380 (2003). 10.1118/1.1543934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. H., Nesbit D. E., Fisher D. R., Fritz S. L., S. J.DwyerIII, Templeton A. W., Lin F., and Jewell W. R., “Computed tomographic mammography using a conventional body scanner,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 138, 553–558 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A., Fukushima H., Okamura R., Nakamura Y., Morimoto T., Urata Y., Mukaihara S., and Hayakawa K., “Dynamic helical CT mammography of breast cancer,” Radiat. Med. 24, 35–40 (2006). 10.1007/BF02489987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Lindfors K. K., and Seibert J. A., “Dedicated breast CT: radiation dose and image quality evaluation,” Radiology 221, 657–667 (2001). 10.1148/radiol.2213010334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M. and Lindfors K. K., “Breast CT: potential for breast cancer screening and diagnosis,” Future Oncol. 2, 351–356 (2006). 10.2217/14796694.2.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning R., Chen B., Conover D., McHugh L., Cullinan J., and Yu R., “Flat panel detector-based cone beam volume CT mammography imaging: Preliminary phantom study,” SPIE 4320, 601–610 (2001). 10.1117/12.430901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick S., Vedantham S., and Karellas A., “Investigation of optimal kVp Settings for CT mammography using a flat panel detector,” SPIE 4682, 392–402 (2002). 10.1117/12.465581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. J., Shaw C. C., Chen L., Altunbas M. C., Liu X., Han T., Wang T., Yang W. T., Whitman G. J., and Tu S. J., “Visibility of microcalcification in cone beam breast CT: effects of X-ray tube voltage and radiation dose,” Med. Phys. 34, 2995–3004 (2007). 10.1118/1.2745921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzymialkiewicz C. N. et al. , “Performance of dedicated emission mammotomography for various breast shapes and sizes,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 5051 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/19/021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. B., Whitehead J., Dorse C., Threatt B. A., F. I.Gilbert, Jr., Present A. J., and Carlile T., “Mammographic Calcifications and Risk of Subsequent Breast Cancer,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85, 230–235 (1993). 10.1093/jnci/85.3.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Vedula A. A., and Glick S. J., “Microcalcification detection using cone-beam CT mammography with a flat-panel imager,” Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 2183–2195 (2004). 10.1088/0031-9155/49/11/005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. and Ning R., “Cone-beam volume CT breast imaging: feasibility study,” Med. Phys. 29, 755–770 (2002). 10.1118/1.1461843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Chen L., Ge S., Yi Y., Han T., Zhong Y., Lai C.-J., Liu X., Wang T., and Shaw C. C., Visibility of Microcalcifications in CCD-Based Cone Beam CT: A Preliminary Study (SPIE, Lake Buena Vista, FL, 2009), p. 72580M-9. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Radiology, “Mammography Quality Standards Act,” (1999).

- Ogawa K., Nakajima M., and Yuta S., “A Reconstruction Algorithm from Truncated Projections,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 3, 34–40 (1984). 10.1109/TMI.1984.4307648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridani A., Finch D. V., Ritman E. L., and Smith K. T., “Local Tomography II,” SIAM J. Appl. Math. 57, 1095–1127 (1997). 10.1137/S0036139995286357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo S., Rizo P., and Grangeat P., Region-of-Interest Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (International Meeting on Fully Three-Dimensional Image Reconstruction In Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, France, 1995), pp. 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Guan H., Yin F.-F., Zhu Y., and Kim J. H., “Adaptive portal CT reconstruction: A simulation study,” Med. Phys. 27, 2209–2214 (2000). 10.1118/1.1312193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chityala R., Hoffmann K. R., Bednarek D. R., and Rudin S., “Region of Interest (ROI) Computed Tomography,” SPIE 5368, 534–541 (2004). 10.1117/12.534568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolditz D., Kyriakou Y., and Kalender W. A., “Volume-of-interest (VOI) imaging in C-arm flat-detector CT for high image quality at reduced dose,” Med. Phys. 37, 2719–2730 (2010). 10.1118/1.3427641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Hoffmann K. R., Ionita C. N., Keleshis C., Bednarek D. R., and Rudin S., “Rotational micro-CT using a clinical C-arm angiography gantry,” Med. Phys. 35, 4757–4764 (2008). 10.1118/1.2989989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass C., Knaup M., Sawall S., and Kachelriess M., Simple ROI Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference, Knoxville, 2010), pp. 3161–6168. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Shaw C. C., Altunbas M. C., Lai C.-J., Liu X., Han T., Wang T., Yang W. T., and Whitman G. J., “Feasibility of volume-of-interest (VOI) scanning technique in cone beam breast CT - a preliminary study,” Med. Phys. 35, 3482–3490 (2008). 10.1118/1.2948397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Zhong Y., Chen L., Lai C.-J., Liu X., Han T., Yi Y., You Z., Ge S., Wang T., and Shaw C. C., Demonstration of Dual Resolution Cone Beam CT Technique with an a-Si/a-Se Flat Panel Detector (SPIE, San Diego, California: 2010), p. 76223B. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Shen Y., Lai C.-J., Han T., Zhong Y., Ge S., Liu X., Wang T., Yang W. T., Whitman G. J., and Shaw C. C., “Dual resolution cone beam breast CT: A feasibility study,” Med. Phys. 36, 4007–4014 (2009). 10.1118/1.3187225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.-J. et al. , “Reduction in x-ray scatter and radiation dose for volume-of-interest (VOI) cone-beam breast CT - a phantom study,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54, 6691 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/21/016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt D., Tousignant O., Demers Y., Laperriere L., and Rowlands J., “Imaging performance of amorphous selenium flat-panel detector for digital fluoroscopy,” Proc. SPIE 5030, 226–234. (2003). 10.1117/12.480131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flat panel sensor C7921CA-09, Catalog by Hamamatsu.

- Flat panel sensor C9312SK-06, Catalog by Hamamatsu.

- Hubbell J. H. and Seltzer S. M., “Tables of X-Ray Mass Attenuation Coefficients and Mass Energy-Absorption Coefficients from 1 keV to 20 MeV for Elements Z = 1 to 92 and 48 Additional Substances of Dosimetric Interest,” NIST table, http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/xraycoef/index.cfm.

- Berger M. J., Coursey J. S., Zucker M. A., and Chang J., “Stopping-Power and Range Tables for Electrons, Protons, and Helium Ions, NIST table,” http://www.nist.gov/pml/data/star/index.cfm.

- Botter-Jensen L., Bulur E., Duller G. A. T., and Murray A. S., “Advances in luminescence instrument systems,” Radiat. Meas. 32, 523–528 (2000). 10.1016/S1350-4487(00)00039-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKeever S. W. S., Blair M. W., Bulur E., Gaza R., Gaza R., Kalchgruber R., Klein D. M., and Yukihara E. G., “Recent advances in dosimetry using the optically stimulated luminescence of Al2O3:C,” Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 109, 269–276 (2004). 10.1093/rpd/nch302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters B. R. B. and Rogers D. W. O., “DOSXYZnrc Users Manual,” (Ionizing Radiation Standards National Research Council of Canada–Ottawa.Ionizing Radiation Standards National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa2004).

- Yi Y., Lai C.-J., Han T., Zhong Y., Shen Y., Liu X., Ge S., You Z., Wang T., and Shaw C. C., “Radiation doses in cone-beam breast computed tomography: A Monte Carlo simulation study,” Med. Phys. 38, 589–597 (2011). 10.1118/1.3521469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]