Abstract

In recent years, the transcription factor serum response factor (SRF) was shown to contribute to various physiological processes linked to neuronal motility. The latter include cell migration, axon guidance, and, e.g., synapse function relying on cytoskeletal dynamics, neurite outgrowth, axonal and dendritic differentiation, growth cone motility, and neurite branching. SRF teams up with myocardin related transcription factors (MRTFs) and ternary complex factors (TCFs) to mediate cellular actin cytoskeletal dynamics and the immediate-early gene (IEG) response, a bona fide indicator of neuronal activation. Herein, I will discuss how SRF and cofactors might modulate physiological processes of neuronal motility. Further, potential mechanisms engaged by neurite growth promoting molecules and axon guidance cues to target SRF’s transcriptional machinery in physiological neuronal motility will be presented. Of note, altered cytoskeletal dynamics and rapid initiation of an IEG response are a hallmark of injured neurons in various neurological disorders. Thus, SRF and its MRTF and TCF cofactors might emerge as a novel trio modulating peripheral and central axon regeneration.

Keywords: SRF, TCF, MRTF, axon, regeneration, neurite, cytoskeleton, IEG

Introduction

Serum response factor (SRF), a MADS box transcription factor (Norman et al., 1988), was originally identified as the gene regulator activated by serum stimulation of starved cells (Posern and Treisman, 2006; Miano et al., 2007; Olson and Nordheim, 2010). Serum response elements (SRE) recognized by SRF are present in a wealth of genes with diverse functions, yet are enriched in two classes of SRF target genes (Philippar et al., 2004; Selvaraj and Prywes, 2004; Sun et al., 2006; Stritt et al., 2009):

-

(i)

Immediate-early genes (IEGs), including genes encoding transcription factors (Curran and Morgan, 1995; Herdegen and Leah, 1998), growth factors (e.g., Ctgf, Bdnf), and, e.g., the synaptic plasticity associated gene Arc (Arg3.1). IEG induction is a rapid – activated within minutes – but transient gene expression response, not requiring new protein synthesis.

-

(ii)

Many genes encoding components of the actin cytoskeleton including actin isoforms (Actb, Actc, Actg, Acta) or ABPs (actin binding proteins; gelsolin, vinculin, transgelin, tropomyosin, myosins, vinculin) are transcriptionally regulated by SRF. Such a unique gene regulatory signature imposed by SRF toward actin cytoskeletal genes has not been described for microtubules and intermediate filaments and any other gene regulator so far.

Besides direct transcriptional regulation, SRF controls – via a post-translational mechanism – activity of the actin severing protein cofilin (Alberti et al., 2005; Mokalled et al., 2010; see also Potential SRF and Cofactor Invoked Mechanisms Modulating Neurite Growth and Regeneration.).

Some genes such as actin isoforms are considered to have both, IEG properties and cytoskeletal functions (Ramanan et al., 2005; Knoll and Nordheim, 2009).

Serum response factor recruits cofactors to mediate the two gene responses outlined above. To convey an IEG response, SRF mainly teams up with ternary complex factors (TCFs) such as Elk-1, Sap-1, and Net (Sharrocks, 2001; Shaw and Saxton, 2003; Buchwalter et al., 2004; Besnard et al., 2011). TCFs are activated by a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade upon serum and growth factor stimulation.

As outlined above, SRF transcriptionally regulates many genes encoding components of the actin cytoskeleton. In turn, SRF’s activity is adjusted by actin treadmilling. In order to respond to changes in cytoplasmic actin dynamics, SRF recruits an “actin sensor” composed by members of the myocardin related transcription factor family (MRTF; Pipes et al., 2006; Posern and Treisman, 2006; Olson and Nordheim, 2010). The mechanism of this “actin sensor” was investigated in most detail for MRTF-A (also named MAL) in non-neuronal cells (Miralles et al., 2003). MRTF-A’s function as a sensor of actin dynamics relies on its capability to bind monomeric actin and – at least in part – on shuttling in and out of the nucleus (Mouilleron et al., 2008).

In un-stimulated cells, monomeric G-actin blocks MRTF-A’s ability to augment SRF’s transcriptional activity by (i) decreasing MRTF-A nuclear import, (ii) enhancing MRTF-A nuclear export in an actin-dependent manner, and (iii) by a nuclear G-actin fraction binding directly to MRTF-A (Vartiainen et al., 2007).

Upon cell stimulation, Rho-GTPases stimulate F-actin assembly and thereby a depletion of the G-actin pool. This liberates MRTF-A from G-actin and allows, e.g., for MRTF-A nuclear entry (Miralles et al., 2003). Notably, Rho-GTPases such as RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac1 are important actin cytoskeletal modulators of neuronal morphology and axonal regeneration (Tahirovic and Bradke, 2009; Hall and Lalli, 2010). Thus, SRF might be a signaling intermediate bridging the impact of Rho-GTPases on cytoskeletal dynamics. In sum, G-actin reduces, whereas F-actin assembly augments SRF-mediated gene activity (Posern et al., 2002, 2004; Posern and Treisman, 2006; Knoll and Nordheim, 2009; Stern et al., 2009; Knoll, 2010; Olson and Nordheim, 2010). This principal mechanism appears to be conserved also in neurons. However, in neurons modifications to this scheme might exist, as constitutive nuclear MRTF localization has been reported as well as MRTF shuttling (Tabuchi et al., 2005; Kalita et al., 2006; Wickramasinghe et al., 2008; Stern et al., 2009; Knoll, 2010).

Myocardin related transcription factors and TCFs may act antagonistically in some instances by competing for SRF occupancy as demonstrated in muscle cells (Wang et al., 2004). In addition, a cross-talk between the upstream pathways of MRTF and TCF activation has been shown. Here, nuclear MAL export is facilitated by ERK1/2 phosphorylation of MAL (Kalita et al., 2006; Muehlich et al., 2008). In contrast, ERK1/2 phosphorylation of the TCF Elk-1 prevents nuclear export and facilitates Elk-1 import into the nucleus. Of note, MRTF can also negatively regulate MAP kinase signaling via regulation of the mitogen-inducible gene 6 (Mig6; Descot et al., 2009)

SRF and Its Cofactors in Physiological Processes Requiring Neuronal Motility

SRF functions in neuronal motility

Up until now, the role of SRF in neuronal motility processes has been investigated in greater detail than its TCF and MRTF cofactors.

The elucidation of SRF functions in neurons has been greatly aided by the availability of Srf mouse mutants (Wiebel et al., 2002; Alberti et al., 2005). Conditional Srf ablation, e.g., in the murine forebrain revealed a wealth of neuronal motility phenotypes (Knoll and Nordheim, 2009).

In early postnatal stages, SRF ablation resulted in impaired tangential cell migration along the rostral migratory stream (Alberti et al., 2005). Besides cell migration, neurite outgrowth, axon vs. dendrite differentiation, and axon guidance of hippocampal and sensory axons were disturbed in Srf mutants (Knoll et al., 2006; Wickramasinghe et al., 2008; Stern et al., 2009). In the hippocampus of SRF-deficient mice, mossy fiber axon guidance was impaired (Knoll et al., 2006). SRF-deficient neurons are frequently bipolar in shape and reduced in neurite length (Knoll et al., 2006; Stern et al., 2009; Stritt and Knoll, 2010). In SRF-deficient mice primary hippocampal or dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons, neurite outgrowth is severely impaired (Knoll et al., 2006; Wickramasinghe et al., 2008). Conversely, overexpression of constitutively active SRF–VP16 enhanced neurite outgrowth in wild-type (Wickramasinghe et al., 2008) and was more pronounced in neurons with SRF-deficiency (Knoll et al., 2006). Thus, in general terms, SRF loss-of-function (LOF) decreases neurite growth. SRF gain-of-function (GOF), e.g., by overexpression of SRF–VP16, stimulates neurite extension (Table 1). The latter finding is of potential relevance in axonal regeneration (see SRF and Cofactors in Pathological Neuronal Motility and Potential SRF and Cofactor Invoked Mechanisms Modulating Neurite Growth and Regeneration.).

Table 1.

Summary of effects imposed on neuronal morphology upon SRF, MRTF and TCF loss of-function (LOF) and gain-of-function (GOF).

| SRF |

MRTF |

TCF |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOF | GOF | LOF | GOF | LOF | GOF | |

| Effect on neuronal morphology | (i) Decreased neurite outgrowth | (i) Increased neurite outgrowth | (i) Decreased neurite outgrowth and dendritic complexity | (i) Enhanced dendritic complexity | Reduced dendritic length | (i) Enhanced dendritic length |

| (ii) Impaired growth cone morphology | (ii) Increased neurite branching | (ii) Enhanced neuronal differentiation | ||||

| (iii) Enhanced cell death | ||||||

| Method | Conditional murine Srf inactivation | Overexpression of SRF–VP16 | (i) Murine Mrtf-a/Mrtf-b inactivation | (i) MRTF-B overexpression | Overexpression of dom.-neg. Elk-1 | (i) Overexpression of const.-active Elk-1 |

| (ii) siRNA mediated knock-down | (ii) Overexpression of wt Elk-1 or sElk-1 | |||||

| (iii) Overexpression of dom.-neg. MRTF-A | (iii) Elk-1 overexpression in dendrites only | |||||

| Cell type | Hippocampal, DRG | Hippocampal, DRG | Hippocampal, cortical, DRG | Cortical | Striatal | (i) Striatal |

| (ii) PC12 cells | ||||||

| (iii) Hippocampal | ||||||

| Reference | Knoll et al. (2006), Wickramasinghe et al. (2008) | Knoll et al. (2006), Wickramasinghe et al. (2008), Stritt and Knoll (2010) | Ishikawa et al. (2010), Knoll et al. (2006), Shiota et al. (2006), Wickramasinghe et al. (2008), O’sullivan et al. (2010), Mokalled et al. (2010) | Ishikawa et al. (2010) | Lavaur et al. (2007) | Vanhoutte et al. (2001), Barrett et al. (2006a), Lavaur et al. (2007) |

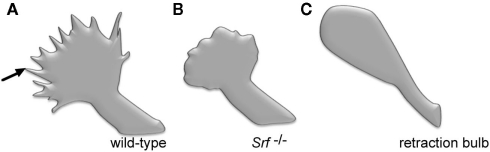

Growth cones of SRF-deficient neurons do not protrude finger-like filopodia and therefore appear rounded in shape (Knoll et al., 2006; Stern et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Notably, retraction bulbs, the growth cone equivalent of transected CNS axons, are likewise rounded-up and frequently also protrude fewer filopodia (Erturk et al., 2007) (Figure 1). Stimulation of growth cone cytoskeletal dynamics with axon guidance cues, such as ephrins (Knoll and Drescher, 2002), results in a transient de-polymerization of the cytoskeleton, the so-called growth cone collapse response (Dent and Gertler, 2003; Pak et al., 2008). The growth cone collapse is thought to allow for directional re-orientation of axons ensuring appropriate axonal target selection in vivo. However, in Srf mutant neurons, actin, (and microtubule) cytoskeletal rearrangements upon guidance cue application failed. This resulted in aberrant growth cone structures consisting of F-actin and microtubule ring-like filaments (Knoll et al., 2006; Stern et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Similar results were also observed in endothelial cells lacking SRF, arguing for an SRF function on cytoskeletal dynamics conserved in various cell types (Franco and Li, 2009).

Figure 1.

Comparison of SRF-deficient growth cones with retraction bulb. (A) Scheme of a growth cone of a wild-type neuron grown in cell culture. The growth cone typically protrudes multiple finger-like filopodia (one is marked by an arrow). (B) A growth cone derived from an SRF-deficient neuron grown in culture. Please note the reduced number of filopodia resulting in a round shape of the growth cone. (C) A so-called retraction bulb, typically found at the end of a transected axon of a wild-type neuron in vivo. Similar to SRF-deficiency (B), retraction bulbs elaborate fewer filopodia. Schematic drawing is based on a figure from Erturk et al. (2007).

Serum response factor ablation in the adult nervous system revealed essential SRF functions in neuronal activity-induced gene expression, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory (Ramanan et al., 2005; Etkin et al., 2006). Here, the IEG Arc, also possessing actin cytoskeleton modulatory properties (Messaoudi et al., 2007), emerges as important SRF and MRTF controlled target gene (Kawashima et al., 2009; Pintchovski et al., 2009; Smith-Hicks et al., 2010). Such an SRF-Arc regulatory unit might be instrumental in structural alterations of synapse function (e.g., spine growth and shape).

MRTF functions in neuronal motility

In vivo function of MRTFs in the brain have recently been investigated employing Mrtf-a/Mrtf-b compound mouse mutants (Mokalled et al., 2010). Srf and Mrtf double mutants share many neuronal phenotypes, suggesting that SRF might mediate many of its functions by MRTF recruitment. Similar to neurons lacking SRF (see SRF Functions in Neuronal Motility), MRTF-A/MRTF-B deficient neurons revealed decreased neurite outgrowth (Mokalled et al., 2010). This is in line with overexpression of dominant-negative MRTF-A in primary hippocampal neurons resulting likewise in decreased neurite growth (Knoll et al., 2006; Shiota et al., 2006). In addition, MRTF-B overexpression or knock-down stimulates and reduces neurite complexity of primary neurons, respectively (Ishikawa et al., 2010; O’sullivan et al., 2010). In contrast MRTF-A knock-down resulted in enhanced neurite complexity, which might be explained by concomitant induction of MRTF-B expression (O’sullivan et al., 2010).

In sum, all data available so far point at a neurite outgrowth promoting function of MRTFs.

TCF functions in neuronal motility

Data available reveal a function of the TCF family member Elk-1 in neurite outgrowth and – of potential relevance for axonal regeneration – also in neuronal survival/apoptosis (Sgambato et al., 1998; Vanhoutte et al., 2001; Barrett et al., 2006a,b; Lavaur et al., 2007; Demir et al., 2009, 2011; Besnard et al., 2011; see Potential SRF and Cofactor Invoked Mechanisms Modulating Neurite Growth and Regeneration). An additional feature of TCFs shared by MRTFs, yet not SRF, is a potential nuclear-to-cytoplasmic shuttling of these gene regulators (Besnard et al., 2011). Wild-type Elk-1, in contrast to a shorter neuron-specific nucleus-restricted Elk-1 isoform (sElk-1), also localizes to the neuronal cytoplasm (Sgambato et al., 1998; Vanhoutte et al., 2001). Upon stimulation however, activated, i.e., phosphorylated Elk-1 appears to re-localize exclusively to the nucleus in vitro. However, in vivo neuronal activation resulted in both constitutive nuclear P-Elk-1 accumulation but also additional cytoplasmic signals (Lavaur et al., 2007). Thus, cytoplasmic vs. nuclear Elk-1 localization might also differentially influence neurite outgrowth. Indeed, nucleus-restricted sElk-1 enhanced the percentage of neuronal-like PC12 cell with neurites (Vanhoutte et al., 2001). Contrastingly, targeting Elk-1 overexpression specifically to the dendrites, resulted in decreased neuronal survival of primary neurons (Barrett et al., 2006a). Overexpression of dominant-negative or constitutively active Elk-1 resulted in Elk-1 localization primarily in the dendrites and nucleus of primary neurons, respectively. Whereas dominant-negative Elk-1 reduced dendritic length, the constitutively active Elk-1 enhanced dendritic length (Lavaur et al., 2007).

So far, TCF analysis in neurons in vivo failed to uncover essential TCF functions in the brain as detailed for SRF and MRTFs above. Investigations of TCF functions are hampered by an apparent functional redundancy among the three main family members. Elk-1 mouse mutants reveal no obvious neuronal phenotype besides a mildly impaired IEG response in the hippocampus (Cesari et al., 2004).

In sum, Elk-1 modulates neuronal motility most likely in a sub-cellular compartment dependent manner.

SRF and Cofactors in Pathological Neuronal Motility

As described in detail above (see SRF and Its Cofactors in Physiological Processes Requiring Neuronal Motility), SRF and cofactors were assigned various functions in shaping neuronal morphology including neurite growth, branching and growth cone shape. Many neurological disorders affect neuronal motility. Chronic seizures for instance, induce exuberant sprouting of mossy fibers emanating from dentate gyrus granule cell neurons. In contrast to this excessive outgrowth of new neurites during status epilepticus, axotomy in the central nervous system, e.g., during spinal cord injury, prevents re-growth of severed nerve fibers.

Due to its intimate link with actin cytoskeletal dynamics, activity of SRF and cofactors might be targeted during such neuro-pathological processes of neuronal motility. Particularly, the potential of SRF–VP16 to stimulate neurite outgrowth (Knoll et al., 2006; Wickramasinghe et al., 2008) and branching (Stritt and Knoll, 2010) of primary neurons might proof valuable for speeding up re-growth and branching of transected axons. In recent years, expression and/or functions of SRF and cofactors has been reported in the course of many neuro-pathological conditions. These include Alzheimer’s disease (Chow et al., 2007; Bell et al., 2009; Sharma et al., 2010), Huntington’s disease (Sharma et al., 2010), epilepsy (Herdegen et al., 1997a; Morris et al., 1999; Hu et al., 2004), de-myelination (Stritt et al., 2009), retinal degeneration (Sandstrom et al., 2011), hyperactivity (Parkitna et al., 2010), hypoxia (Jiang et al., 2009; Cao et al., 2011), resilience to chronical stress (Vialou et al., 2010), and alcohol addiction (Paul et al., 2010). However so far, functional data of SRF or one of its cofactors in axonal regeneration are not available. Yet looking at regeneration processes in other organs, SRF has already been implicated in, e.g., ulcer healing, muscle, and hepatocyte regeneration (Chai and Tarnawski, 2002).

Interestingly, most data on roles of SRF and its cofactors in axonal injury available so far are derived from investigations focusing on TCFs, namely Elk-1. This might be due to the intimate link of TCFs such as Elk-1 and induction of an IEG response upon axonal injury (see Potential SRF and Cofactor Invoked Mechanisms Modulating Neurite Growth and Regeneration).

As indicated above, so far functional data on SRF and cofactors in axonal regeneration are not reported. However, expression profiles of SRF and TCFs, but not MRTFs, after axonal injury have been investigated (Herdegen and Zimmermann, 1995; Herdegen et al., 1997a; Lin et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2004; Sung et al., 2004; Perlson et al., 2005; Kerr et al., 2010).

In a first study, Perlson et al. (2005) demonstrated up-regulation of activated Elk-1 (P-Elk-1) in the nucleus within 10 min after DRG neuron axotomy. Notably, this P-Elk-1 induction was abolished in mice lacking the intermediate filament vimentin (Perlson et al., 2005). This increase in P-Elk-1 is most likely not due to novel Elk-1 mRNA synthesis, as recently demonstrated (Kerr et al., 2010). In this study, mRNA levels of various TCF family members were analyzed upon sciatic nerve lesion. Whereas Net (Elk-3) mRNA expression was strongly induced upon lesion, Elk-1 mRNA abundance remained unaltered. The induction of nucleus-restricted P-Elk-1 on protein level observed in lesioned DRG neurons (Perlson et al., 2005) was confirmed in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury in the hippocampal system (Hu et al., 2004). Further, elevated P-Elk-1 levels were observed in an Aplysia model of nerve crush (Lin et al., 2003; Sung et al., 2004). These findings suggests that Elk-1 activity in injured neurons is mainly regulated by post-translational, i.e., phosphorylation, rather than transcriptional mechanisms.

A first study analyzing both Elk-1 and SRF in neuronal injury was provided by Lin et al. (2003). Here, the authors provide data arguing for occupancy of a c-fos derived SRE by Elk-1 and SRF in both injured pleuropedal Aplysia and mouse DRG neurons. In contrast to DRG neurons, altered SRF expression was not found in other peripheral neuron lesion models including the optic and facial nerve (Herdegen et al., 1997a).

In sum, although far from being complete, data available so far mainly focusing on peripheral nerve injury indicate that Elk-1 and also SRF activity are targeted by axonal transection. Future studies will have to address SRF and cofactor expression also in central axon injury models. In addition, it will be important to expand analysis to various (short and longer) time-points after injury also including additional SRF and cofactor anti-sera.

Potential SRF and Cofactor Invoked Mechanisms Modulating Neurite Growth and Regeneration

Serum response factor and cofactors can potentially regulate a wealth of different target genes, depending on, e.g., cell and stimulus type. As outlined above (see Introduction), SRF-mediated gene regulation has been analyzed in greatest depth in the IEG response and for genes encoding components of the actin cytoskeleton. Therefore, I will propose potential mechanism by which SRF and cofactors might modulate neuronal motility involving IEGs and cytoskeletal gene products.

IEG activation and neuronal functions

The induction of IEGs, primarily those encoding transcriptional regulators such as c-Jun, by axonal injury is a well-established response observed in various neuronal populations (Morgan et al., 1987; Haas et al., 1993; Hull and Bahr, 1994; Curran and Morgan, 1995; Robinson, 1995; Herdegen et al., 1997a,b; Herdegen and Leah, 1998; Herdegen and Waetzig, 2001; Moran and Graeber, 2004; Raivich et al., 2004; Raivich and Behrens, 2006; Raivich, 2008). Besides changes in expression level, individual IEGs such as c-Jun are indispensable for peripheral axon regeneration, e.g., of facial motor neurons (Raivich et al., 2004). IEG induction is rapid, yet transient, suggesting an involvement of IEGs in early stages of neuronal differentiation and axonal injury processes. Of note, many IEGs encode transcription factors (c-Fos, Egr-1, Egr2, Fosb, JunB, c-Jun) under SRF-mediated gene transcription (Posern and Treisman, 2006; Knoll and Nordheim, 2009; Olson and Nordheim, 2010). Thus, a hierarchical cascade of gene regulators with SRF acting upstream of IEGs might operate and diverge the single axonal injury signal into various gene expression programs.

How might IEGs, transcriptionally regulated, e.g., via an SRF–TCF transcription complex, contribute to physiological and pathological neuronal motility? IEGs are well-established regulators of both, neuronal apoptosis and cell survival (Chen et al., 1995; Herdegen and Leah, 1998; Hughes et al., 1999; Raivich, 2008; Durchdewald et al., 2009). Thus, depending on, e.g., neuron type, severity of lesion applied (e.g., crush vs. complete transection), and time-point after injury, IEGs might induce cell death or enhance survival of injured motorneurons (Figure 2). In line with such an IEG function, TCFs have been implicated as regulators of neuronal apoptosis in vitro. Overexpression of Elk-1 in primary neurons triggered cell death (Barrett et al., 2006a,b), a function involving an association of Elk-1 with mitochondria (Barrett et al., 2006b). In contrast, Demir et al. (2011) recently demonstrated that Elk-1 overexpression in PC12 cells had a pro-survival effect. This discrepancy might be due to cell type specific Elk-1 effects and – importantly – a sub-cellular compartment specific Elk-1 function. The latter is supported by findings demonstrating that overexpression of Elk-1 restricted to dendrites, but not in the nucleus, was able to induce cell death (Barrett et al., 2006a). Thus, the sub-cellular localization of TCFs such as Elk-1 upon axonal injury might be decisive in regulation of a potential survival or pro-apoptotic TCF function in, e.g., axonal regeneration. In such a scenario, Elk-1 might contribute to axonal regeneration not only by a nuclear but also by a cytoplasmic function.

Figure 2.

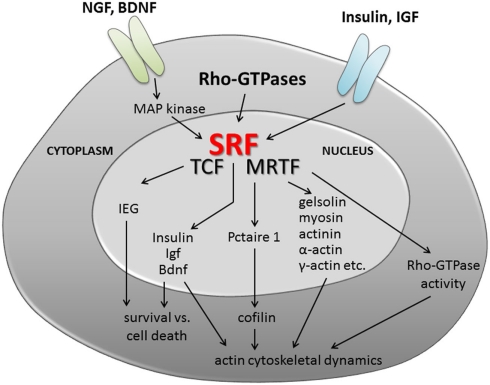

Serum response factor signaling in neuronal motility. Summary of potential upstream signaling cascades activating SRF and/or TCF/MRTF cofactor activity. In addition, possible scenarios on the impact of SRF-mediated gene transcription on neuronal differentiation and axonal regeneration are provided. The latter include regulation of cell survival (e.g., via IEGs, neurotrophin, and insulin growth factors) and cytoskeletal dynamics. Here, SRF and most likely MRTFs will adjust mRNA levels of genes encoding cytoskeletal genes (gelsolin, actin isoforms, etc.) and modulate activity of the actin severing protein cofilin. Further, SRF might adjust Rho-GTPase activity and thereby modulate actin (and microtubule) polymerization.

Serum response factor (Chang et al., 2004) and MRTF (Cao et al., 2011) overexpression protects neurons from cell death in cell culture. In contrast, in vivo no major SRF contribution to regulation of neuronal cell survival and apoptosis during brain development and physiological function has been reported (Knoll and Nordheim, 2009).

Besides apoptosis/cell survival, IEGs such as Egr-1, c-Fos and c-Jun may directly modulate neurite outgrowth in vitro (Jessen et al., 2001; Levkovitz et al., 2001; Eminel et al., 2008). However, enhanced neurite outgrowth might be coupled with or as a consequence of a potential pro-survival IEG function. In addition, the IEG Arc – also controlling actin cytoskeletal dynamics – is regulated by synaptic activity (Plath et al., 2006; Smith-Hicks et al., 2010) summarized in (Shepherd and Bear, 2011). Thus, SRF-controlled IEGs might not only contribute to early phases of axonal regeneration when survival/cell death decisions are made, but also at later stages, e.g., during synaptic targeting and function of successfully regenerated axons.

Cytoskeletal dynamics and neuronal motility

Along with microtubules, actin is a major cytoskeletal component involved during neuronal motility (Dent and Gertler, 2003; Pak et al., 2008; Tahirovic and Bradke, 2009). In contrast to microtubules (Erturk et al., 2007) which have been extensively investigated in retraction bulbs of injured axons in vivo, the actin cytoskeleton has not been analyzed so far in the same depth. Also, whereas interference with microtubule function enhances axonal regeneration in vivo (Hellal et al., 2011), depletion of the major neuronal actin variant β-actin did not affect motor axon regeneration in vivo (Cheever et al., 2011). In line with this, overexpression of β-actin in SRF-deficient neurons alone was not sufficient to rescue neurite outgrowth (Knoll et al., 2006). This might suggest that ABPs and/or other actin isoforms (e.g., α-actin or γ-actin) are more crucial for neurite outgrowth and axonal regeneration processes. Indeed, actin isoforms (Tetzlaff et al., 1988, 1991; Mizobuchi et al., 1990; Tetzlaff and Bisby, 1990; Bisby and Tetzlaff, 1992; Lund and Mcquarrie, 1996; Riley and Bernstein, 1996; Lund et al., 2002; Avwenagha et al., 2003; Moran and Graeber, 2004; Willis et al., 2005) and ABPs such as thymosin (Mollinari et al., 2009), myosins (Jian et al., 1996), GAP-43 (Tetzlaff et al., 1991; Avwenagha et al., 2003), integrins (Werner et al., 2000), and, e.g., coronins (Di Giovanni et al., 2005) are up-regulated upon axonal injury in various instances. Myosin expression has been shown to overcome in vitro neurite outgrowth barriers associated with axonal regeneration (Kubo et al., 2008). As genes encoding myosin components are SRF-regulated (Knoll and Nordheim, 2009; Olson and Nordheim, 2010), SRF might contribute to neurite outgrowth processes in development and pathology by transcriptional regulation of myosin and other promoters regulating expression of actin associated genes (Figure 2).

Besides transcriptional regulation, SRF can modulate activity of the actin severing proteins cofilin and gelsolin (Alberti et al., 2005; Mokalled et al., 2010). Elevated P-cofilin levels, representing inactive cofilin, were reported in SRF- and MRTF-deficient neurons (Alberti et al., 2005; Mokalled et al., 2010). This suggests that wild-type SRF–MRTF signaling activates cofilin, a mechanism involving the CDK5 interacting kinase Pctaire1 (Mokalled et al., 2010). Cofilin is phosphorylated and de-phosphorylated by LIM-kinases and slingshot phosphatases, respectively (Bernstein and Bamburg, 2010). Importantly, this LIM-kinase–cofilin–slingshot regulatory unit is crucially involved in neurite outgrowth on regeneration inhibiting substrates such as Nogo (Hsieh et al., 2006). Inactive cofilin might prevent actin treadmilling and, e.g., de novo formation of F-actin filaments during processes relying on neuronal motility such as neurite outgrowth, branch formation or growth cone turning. In fact, the presence of inactivated cofilin in SRF-deficient neurons may explain the perseverance of F-actin positive actin rings in growth cones upon incubation with collapsing agents such as ephrins (Knoll et al., 2006). Thus, adjusting cofilin activity by SRF might emerge as one major mechanism by which SRF–MRTF can regulate neuronal motility (Figure 2).

In addition, SRF might modulate neuronal motility by interaction with signaling molecules positioned upstream of cofilin such as Rho-GTPases. In recruiting downstream effectors such as Rho-kinase, Rho-GTPases modulate the actin cytoskeleton, and – importantly – also microtubules. Rho-GTPases are well-known activators of SRF activity (Hill et al., 1995; Posern and Treisman, 2006; Olson and Nordheim, 2010). In turn, SRF-deficiency altered Rho-GTPase activity (Stritt and Knoll, 2010), suggesting a tight regulatory loop between Rho-GTPases and SRF. Rho-GTPases, particularly RhoA are well-known downstream effectors mediating the growth inhibitory potential of Nogo, MAG and other myelin associated regeneration inhibitors (Filbin, 2003; Yiu and He, 2006). In addition, Rho-GTPases modulate neuronal motility, e.g., neurite outgrowth and polarization (Govek et al., 2005; Tahirovic and Bradke, 2009; Hall and Lalli, 2010). Thus, although data are currently not available, it might be tempting to speculate that Rho-GTPases interact with SRF-mediated transcription during physiological and regenerative neuronal motility processes (Figure 2). As so far, MRTFs have been shown to connect Rho-GTPase–actin with SRF signaling, it is likely that MRTFs are the crucial cofactors teaming up with SRF during these functions.

SRF’s impact on growth factor signaling in neuronal motility

Many growth factors modulate neurite outgrowth and axonal regeneration. With regard to neuronal SRF-mediated transcriptional regulation, two growth factor signaling pathways might proof important for conveying SRF’s impact on neuronal motility.

First, neurotrophins such as BDNF and NGF activate SRF-mediated transcription (Chang et al., 2004; Kalita et al., 2006; Wickramasinghe et al., 2008; Stritt and Knoll, 2010) and SRF expression (Kalita et al., 2006). Data available so far suggest a recruitment of MAP kinases upon neurotrophin signaling to activate SRF. As neurotrophins are implicated in neuronal survival, neurite outgrowth, growth cone morphology, and axonal regeneration (Gallo and Letourneau, 2004; Lykissas et al., 2007), SRF, and cofactors might be targeted by signaling cascades triggered by neurotrophins. Additionally, Bdnf mRNA levels were reduced in Srf mutant neurons, suggesting induction of the Bdnf promoter by wild-type SRF (Etkin et al., 2006). Thus, SRF might be employed to adjust BDNF levels available to neurons and thereby influence axonal injury (Figure 2).

Secondly, SRF emerges as transcriptional regulator of many genes encoding components of insulin or insulin growth factor (IGF) signaling in neurons and non-neuronal cells. These genes include the insulin gene (Sarkar et al., 2011), Igf1 (Charvet et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2009), and, e.g., Ctgf, a protein harboring an IGF binding domain (Stritt et al., 2009). Such SRF-mediated control of insulin/IGF regulation in neurons was also demonstrated to affect neighboring cells, i.e., oligodendrocytes, in a paracrine manner (Stritt et al., 2009). In addition, insulin signaling augmented TCF occupancy at SREs (Thompson et al., 1994) and insulin resistance in muscles is associated with altered SRF–MRTF activity (Jin et al., 2011). Notably, insulin/IGF signaling regulates neurite outgrowth (Ozdinler and Macklis, 2006) and can increase regeneration properties of transected axons (Near et al., 1992; Ishii et al., 1994; Fu and Gordon, 1997). SRF might also be connected to glial scar formation, a major physical barrier of CNS axon regeneration. This might be accomplished by regulation of CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) levels, a secreted protein associated with fibronectin function and scar formation (Hertel et al., 2000; Conrad et al., 2005).

In sum, SRF gene regulation might modulate insulin/IGF signaling during physiological neuronal motility processes as well as in injured neurons (Figure 2).

Outlook

Wild-type SRF and cofactors can modulate many mechanisms such as an IEG response, actin cytoskeletal dynamics, and growth factor signaling which contribute to neuronal motility in development and, e.g., axonal injury. Future experiments will have to address directly, e.g., employing conditional Srf or Mrtf mutagenesis or TCF compound mutants, whether SRF and cofactors are key players in axonal regeneration. In this regard, performing GOF experiments employing SRF–VP16, a known in vitro stimulator of neurite outgrowth, in in vivo axonal regeneration paradigms might be particularly rewarding.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Bernd Knöll is supported by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) through the Emmy Noether program and through grants of the Schram, Gottschalk, and Gemeinnützige Hertie foundation.

References

- Alberti S., Krause S. M., Kretz O., Philippar U., Lemberger T., Casanova E., Wiebel F. F., Schwarz H., Frotscher M., Schutz G., Nordheim A. (2005). Neuronal migration in the murine rostral migratory stream requires serum response factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6148–6153 10.1073/pnas.0501191102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avwenagha O., Campbell G., Bird M. M. (2003). Distribution of GAP-43, beta-III tubulin and F-actin in developing and regenerating axons and their growth cones in vitro, following neurotrophin treatment. J. Neurocytol. 32, 1077–1089 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000021903.24849.6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L. E., Sul J. Y., Takano H., Van Bockstaele E. J., Haydon P. G., Eberwine J. H. (2006a). Region-directed phototransfection reveals the functional significance of a dendritically synthesized transcription factor. Nat. Methods 3, 455–460 10.1038/nmeth885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L. E., Van Bockstaele E. J., Sul J. Y., Takano H., Haydon P. G., Eberwine J. H. (2006b). Elk-1 associates with the mitochondrial permeability transition pore complex in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5155–5160 10.1073/pnas.0510477103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. D., Deane R., Chow N., Long X., Sagare A., Singh I., Streb J. W., Guo H., Rubio A., Van Nostrand W., Miano J. M., Zlokovic B. V. (2009). SRF and myocardin regulate LRP-mediated amyloid-beta clearance in brain vascular cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 143–153 10.1038/ncb1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein B. W., Bamburg J. R. (2010). ADF/cofilin: a functional node in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 187–195 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard A., Galan-Rodriguez B., Vanhoutte P., Caboche J. (2011). Elk-1 a transcription factor with multiple facets in the brain. Front. Neurosci. 5:35. 10.3389/fnins.2011.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisby M. A., Tetzlaff W. (1992). Changes in cytoskeletal protein synthesis following axon injury and during axon regeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 6, 107–123 10.1007/BF02780547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwalter G., Gross C., Wasylyk B. (2004). Ets ternary complex transcription factors. Gene 324, 1–14 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. L., Hu X. M., Hu J. Q., Zheng W. X. (2011). Myocardin-related transcription factor-A promoting neuronal survival against apoptosis induced by hypoxia/ischemia. Brain Res. 1385, 263–274 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari F., Brecht S., Vintersten K., Vuong L. G., Hofmann M., Klingel K., Schnorr J. J., Arsenian S., Schild H., Herdegen T., Wiebel F. F., Nordheim A. (2004). Mice deficient for the ets transcription factor elk-1 show normal immune responses and mildly impaired neuronal gene activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 294–305 10.1128/MCB.24.1.294-305.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J., Tarnawski A. S. (2002). Serum response factor: discovery, biochemistry, biological roles and implications for tissue injury healing. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 53, 147–157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. H., Poser S., Xia Z. (2004). A novel role for serum response factor in neuronal survival. J. Neurosci. 24, 2277–2285 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4868-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvet C., Houbron C., Parlakian A., Giordani J., Lahoute C., Bertrand A., Sotiropoulos A., Renou L., Schmitt A., Melki J., Li Z., Daegelen D., Tuil D. (2006). New role for serum response factor in postnatal skeletal muscle growth and regeneration via the interleukin 4 and insulin-like growth factor 1 pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 6664–6674 10.1128/MCB.00138-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever T. R., Olson E. A., Ervasti J. M. (2011). Axonal regeneration and neuronal function are preserved in motor neurons lacking ss-actin in vivo. PLoS ONE 6, e17768. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. C., Curran T., Morgan J. I. (1995). Apoptosis in the nervous system: new revelations. J. Clin. Pathol. 48, 7–12 10.1136/jcp.48.1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow N., Bell R. D., Deane R., Streb J. W., Chen J., Brooks A., Van Nostrand W., Miano J. M., Zlokovic B. V. (2007). Serum response factor and myocardin mediate arterial hypercontractility and cerebral blood flow dysregulation in Alzheimer’s phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 823–828 10.1073/pnas.0610946104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad S., Schluesener H. J., Adibzahdeh M., Schwab J. M. (2005). Spinal cord injury induction of lesional expression of profibrotic and angiogenic connective tissue growth factor confined to reactive astrocytes, invading fibroblasts and endothelial cells. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2, 319–326 10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T., Morgan J. I. (1995). Fos: an immediate-early transcription factor in neurons. J. Neurobiol. 26, 403–412 10.1002/neu.480260312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir O., Aysit N., Onder Z., Turkel N., Ozturk G., Sharrocks A. D., Kurnaz I. A. (2011). ETS-domain transcription factor Elk-1 mediates neuronal survival: SMN as a potential target. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1812, 652–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir O., Korulu S., Yildiz A., Karabay A., Kurnaz I. A. (2009). Elk-1 interacts with neuronal microtubules and relocalizes to the nucleus upon phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 40, 111–119 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent E. W., Gertler F. B. (2003). Cytoskeletal dynamics and transport in growth cone motility and axon guidance. Neuron 40, 209–227 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00633-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descot A., Hoffmann R., Shaposhnikov D., Reschke M., Ullrich A., Posern G. (2009). Negative regulation of the EGFR-MAPK cascade by actin-MAL-mediated Mig6/Errfi-1 induction. Mol. Cell 35, 291–304 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni S., De Biase A., Yakovlev A., Finn T., Beers J., Hoffman E. P., Faden A. I. (2005). In vivo and in vitro characterization of novel neuronal plasticity factors identified following spinal cord injury. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2084–2091 10.1074/jbc.M411975200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durchdewald M., Angel P., Hess J. (2009). The transcription factor Fos: a Janus-type regulator in health and disease. Histol. Histopathol. 24, 1451–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eminel S., Roemer L., Waetzig V., Herdegen T. (2008). c-Jun N-terminal kinases trigger both degeneration and neurite outgrowth in primary hippocampal and cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 104, 957–969 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erturk A., Hellal F., Enes J., Bradke F. (2007). Disorganized microtubules underlie the formation of retraction bulbs and the failure of axonal regeneration. J. Neurosci. 27, 9169–9180 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0612-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A., Alarcon J. M., Weisberg S. P., Touzani K., Huang Y. Y., Nordheim A., Kandel E. R. (2006). A role in learning for SRF: deletion in the adult forebrain disrupts ltd and the formation of an immediate memory of a novel context. Neuron 50, 127–143 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filbin M. T. (2003). Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 703–713 10.1038/nrn1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco C. A., Li Z. (2009). SRF in angiogenesis: Branching the vascular system. Cell Adh. Migr. 3, 264–267 10.4161/cam.3.3.8291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S. Y., Gordon T. (1997). The cellular and molecular basis of peripheral nerve regeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 14, 67–116 10.1007/BF02740621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G., Letourneau P. C. (2004). Regulation of growth cone actin filaments by guidance cues. J. Neurobiol. 58, 92–102 10.1002/neu.10282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govek E. E., Newey S. E., Van Aelst L. (2005). The role of the Rho GTPases in neuronal development. Genes Dev. 19, 1–49 10.1101/gad.1256405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas C. A., Donath C., Kreutzberg G. W. (1993). Differential expression of immediate early genes after transection of the facial nerve. Neuroscience 53, 91–99 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90287-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A., Lalli G. (2010). Rho and Ras GTPases in axon growth, guidance, and branching. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a001818. 10.1101/cshperspect.a001818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellal F., Hurtado A., Ruschel J., Flynn K. C., Laskowski C. J., Umlauf M., Kapitein L. C., Strikis D., Lemmon V., Bixby J., Hoogenraad C. C., Bradke F. (2011). Microtubule stabilization reduces scarring and causes axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Science 331, 928–931 10.1126/science.1201148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Blume A., Buschmann T., Georgakopoulos E., Winter C., Schmid W., Hsieh T. F., Zimmermann M., Gass P. (1997a). Expression of activating transcription factor-2, serum response factor and cAMP/Ca response element binding protein in the adult rat brain following generalized seizures, nerve fibre lesion and ultraviolet irradiation. Neuroscience 81, 199–212 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00170-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Skene P., Bahr M. (1997b). The c-Jun transcription factor–bipotential mediator of neuronal death, survival and regeneration. Trends Neurosci. 20, 227–231 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)01000-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Leah J. D. (1998). Inducible and constitutive transcription factors in the mammalian nervous system: control of gene expression by Jun, Fos and Krox, and CREB/ATF proteins. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 28, 370–490 10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00018-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Waetzig V. (2001). AP-1 proteins in the adult brain: facts and fiction about effectors of neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Oncogene 20, 2424–2437 10.1038/sj.onc.1204387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T., Zimmermann M. (1995). Immediate early genes (IEGs) encoding for inducible transcription factors (ITFs) and neuropeptides in the nervous system: functional network for long-term plasticity and pain. Prog. Brain Res. 104, 299–321 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61797-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel M., Tretter Y., Alzheimer C., Werner S. (2000). Connective tissue growth factor: a novel player in tissue reorganization after brain injury? Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 376–380 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. S., Wynne J., Treisman R. (1995). The Rho family GTPases RhoA, Rac1, and CDC42Hs regulate transcriptional activation by SRF. Cell 81, 1159–1170 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S. H., Ferraro G. B., Fournier A. E. (2006). Myelin-associated inhibitors regulate cofilin phosphorylation and neuronal inhibition through LIM kinase and Slingshot phosphatase. J. Neurosci. 26, 1006–1015 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2806-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Liu C., Bramlett H., Sick T. J., Alonso O. F., Chen S., Dietrich W. D. (2004). Changes in trkB-ERK1/2-CREB/Elk-1 pathways in hippocampal mossy fiber organization after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 24, 934–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes P. E., Alexi T., Walton M., Williams C. E., Dragunow M., Clark R. G., Gluckman P. D. (1999). Activity and injury-dependent expression of inducible transcription factors, growth factors and apoptosis-related genes within the central nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 57, 421–450 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull M., Bahr M. (1994). Regulation of immediate-early gene expression in rat retinal ganglion cells after axotomy and during regeneration through a peripheral nerve graft. J. Neurobiol. 25, 92–105 10.1002/neu.480250109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii D. N., Glazner G. W., Pu S. F. (1994). Role of insulin-like growth factors in peripheral nerve regeneration. Pharmacol. Ther. 62, 125–144 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M., Nishijima N., Shiota J., Sakagami H., Tsuchida K., Mizukoshi M., Fukuchi M., Tsuda M., Tabuchi A. (2010). Involvement of the serum response factor coactivator megakaryoblastic leukemia (MKL) in the activin-regulated dendritic complexity of rat cortical neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32734–32743 10.1074/jbc.M110.137034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen U., Novitskaya V., Pedersen N., Serup P., Berezin V., Bock E. (2001). The transcription factors CREB and c-Fos play key roles in NCAM-mediated neuritogenesis in PC12-E2 cells. J. Neurochem. 79, 1149–1160 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian X., Szaro B. G., Schmidt J. T. (1996). Myosin light chain kinase: expression in neurons and upregulation during axon regeneration. J. Neurobiol. 31, 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Yang W., Huang P., Bu X., Zhang N., Li J. (2009). Increased phosphorylation of Ets-like transcription factor-1 in neurons of hypoxic preconditioned mice. Neurochem. Res. 34, 1443–1450 10.1007/s11064-009-9931-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W., Goldfine A. B., Boes T., Henry R. R., Ciaraldi T. P., Kim E. Y., Emecan M., Fitzpatrick C., Sen A., Shah A., Mun E., Vokes V., Schroeder J., Tatro E., Jimenez-Chillaron J., Patti M. E. (2011). Increased SRF transcriptional activity in human and mouse skeletal muscle is a signature of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 918–929 10.1172/JCI43584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalita K., Kharebava G., Zheng J. J., Hetman M. (2006). Role of megakaryoblastic acute leukemia-1 in ERK1/2-dependent stimulation of serum response factor-driven transcription by BDNF or increased synaptic activity. J. Neurosci. 26, 10020–10032 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2644-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T., Okuno H., Nonaka M., Adachi-Morishima A., Kyo N., Okamura M., Takemoto-Kimura S., Worley P. F., Bito H. (2009). Synaptic activity-responsive element in the Arc/Arg3.1 promoter essential for synapse-to-nucleus signaling in activated neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 316–321 10.1073/pnas.0813276106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr N., Pintzas A., Holmes F., Hobson S. A., Pope R., Wallace M., Wasylyk C., Wasylyk B., Wynick D. (2010). The expression of ELK transcription factors in adult DRG: Novel isoforms, antisense transcripts and upregulation by nerve damage. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 44, 165–177 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll B. (2010). Actin-mediated gene expression in neurons: the MRTF-SRF connection. Biol. Chem. 391, 591–597 10.1515/BC.2010.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll B., Drescher U. (2002). Ephrin-As as receptors in topographic projections. Trends Neurosci. 25, 145–149 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll B., Kretz O., Fiedler C., Alberti S., Schutz G., Frotscher M., Nordheim A. (2006). Serum response factor controls neuronal circuit assembly in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 195–204 10.1038/nn1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll B., Nordheim A. (2009). Functional versatility of transcription factors in the nervous system: the SRF paradigm. Trends Neurosci. 32, 432–442 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T., Endo M., Hata K., Taniguchi J., Kitajo K., Tomura S., Yamaguchi A., Mueller B. K., Yamashita T. (2008). Myosin IIA is required for neurite outgrowth inhibition produced by repulsive guidance molecule. J. Neurochem. 105, 113–126 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavaur J., Bernard F., Trifilieff P., Pascoli V., Kappes V., Pages C., Vanhoutte P., Caboche J. (2007). A TAT-DEF-Elk-1 peptide regulates the cytonuclear trafficking of Elk-1 and controls cytoskeleton dynamics. J. Neurosci. 27, 14448–14458 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkovitz Y., O’donovan K. J., Baraban J. M. (2001). Blockade of NGF-induced neurite outgrowth by a dominant-negative inhibitor of the egr family of transcription regulatory factors. J. Neurosci. 21, 45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Bao J., Sung Y. J., Walters E. T., Ambron R. T. (2003). Rapid electrical and delayed molecular signals regulate the serum response element after nerve injury: convergence of injury and learning signals. J. Neurobiol. 57, 204–220 10.1002/neu.10275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund L. M., Machado V. M., Mcquarrie I. G. (2002). Increased beta-actin and tubulin polymerization in regrowing axons: relationship to the conditioning lesion effect. Exp. Neurol. 178, 306–312 10.1006/exnr.2002.8034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund L. M., Mcquarrie I. G. (1996). Axonal regrowth upregulates beta-actin and Jun D mRNA expression. J. Neurobiol. 31, 476–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykissas M. G., Batistatou A. K., Charalabopoulos K. A., Beris A. E. (2007). The role of neurotrophins in axonal growth, guidance, and regeneration. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 4, 143–151 10.2174/156720207780637216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi E., Kanhema T., Soule J., Tiron A., Dagyte G., Da Silva B., Bramham C. R. (2007). Sustained Arc/Arg3 1 synthesis controls long-term potentiation consolidation through regulation of local actin polymerization in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci 27, 10445–10455 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2883-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miano J. M., Long X., Fujiwara K. (2007). Serum response factor: master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C70–C81 10.1152/ajpcell.00386.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles F., Posern G., Zaromytidou A. I., Treisman R. (2003). Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell 113, 329–342 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00278-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi T., Yagi Y., Mizuno A. (1990). Changes in alpha-tubulin and actin gene expression during optic nerve regeneration in frog retina. J. Neurochem. 55, 54–59 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08820.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokalled M. H., Johnson A., Kim Y., Oh J., Olson E. N. (2010). Myocardin-related transcription factors regulate the Cdk5/Pctaire1 kinase cascade to control neurite outgrowth, neuronal migration and brain development. Development 137, 2365–2374 10.1242/dev.047605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinari C., Ricci-Vitiani L., Pieri M., Lucantoni C., Rinaldi A. M., Racaniello M., De Maria R., Zona C., Pallini R., Merlo D., Garaci E. (2009). Downregulation of thymosin beta4 in neural progenitor grafts promotes spinal cord regeneration. J. Cell Sci. 122, 4195–4207 10.1242/jcs.056895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran L. B., Graeber M. B. (2004). The facial nerve axotomy model. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 44, 154–178 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. I., Cohen D. R., Hempstead J. L., Curran T. (1987). Mapping patterns of c-fos expression in the central nervous system after seizure. Science 237, 192–197 10.1126/science.3629250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris T. A., Jafari N., Rice A. C., Vasconcelos O., Delorenzo R. J. (1999). Persistent increased DNA-binding and expression of serum response factor occur with epilepsy-associated long-term plasticity changes. J. Neurosci. 19, 8234–8243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouilleron S., Guettler S., Langer C. A., Treisman R., Mcdonald N. Q. (2008). Molecular basis for G-actin binding to RPEL motifs from the serum response factor coactivator MAL. EMBO J. 27, 3198–3208 10.1038/emboj.2008.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlich S., Wang R., Lee S. M., Lewis T. C., Dai C., Prywes R. (2008). Serum-induced phosphorylation of the serum response factor coactivator MKL1 by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway inhibits its nuclear localization. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 6302–6313 10.1128/MCB.00427-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near S. L., Whalen L. R., Miller J. A., Ishii D. N. (1992). Insulin-like growth factor II stimulates motor nerve regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 11716–11720 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman C., Runswick M., Pollock R., Treisman R. (1988). Isolation and properties of cDNA clones encoding SRF, a transcription factor that binds to the c-fos serum response element. Cell 55, 989–1003 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90244-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson E. N., Nordheim A. (2010). Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 353–365 10.1038/nrm2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’sullivan N. C., Pickering M., Di Giacomo D., Loscher J. S., Murphy K. J. (2010). Mkl transcription cofactors regulate structural plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1915–1925 10.1093/cercor/bhp262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdinler P. H., Macklis J. D. (2006). IGF-I specifically enhances axon outgrowth of corticospinal motor neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1371–1381 10.1038/nn1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak C. W., Flynn K. C., Bamburg J. R. (2008). Actin-binding proteins take the reins in growth cones. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 136–147 10.1038/nrn2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkitna J. R., Bilbao A., Rieker C., Engblom D., Piechota M., Nordheim A., Spanagel R., Schutz G. (2010). Loss of the serum response factor in the dopamine system leads to hyperactivity. FASEB J. 24, 2427–2435 10.1096/fj.09-151423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A. P., Pohl-Guimaraes F., Krahe T. E., Filgueiras C. C., Lantz C. L., Colello R. J., Wang W., Medina A. E. (2010). Overexpression of serum response factor restores ocular dominance plasticity in a model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J. Neurosci. 30, 2513–2520 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5840-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E., Hanz S., Ben-Yaakov K., Segal-Ruder Y., Seger R., Fainzilber M. (2005). Vimentin-dependent spatial translocation of an activated MAP kinase in injured nerve. Neuron 45, 715–726 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippar U., Schratt G., Dieterich C., Muller J. M., Galgoczy P., Engel F. B., Keating M. T., Gertler F., Schule R., Vingron M., Nordheim A. (2004). The SRF Target Gene Fhl2 Antagonizes RhoA/MAL-Dependent Activation of SRF. Mol. Cell 16, 867–880 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintchovski S. A., Peebles C. L., Kim H. J., Verdin E., Finkbeiner S. (2009). The serum response factor and a putative novel transcription factor regulate expression of the immediate-early gene Arc/Arg3.1 in neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 1525–1537 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5575-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipes G. C., Creemers E. E., Olson E. N. (2006). The myocardin family of transcriptional coactivators: versatile regulators of cell growth, migration, and myogenesis. Genes Dev. 20, 1545–1556 10.1101/gad.1428006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath N., Ohana O., Dammermann B., Errington M. L., Schmitz D., Gross C., Mao X., Engelsberg A., Mahlke C., Welzl H., Kobalz U., Stawrakakis A., Fernandez E., Waltereit R., Bick-Sander A., Therstappen E., Cooke S. F., Blanquet V., Wurst W., Salmen B., Bosl M. R., Lipp H. P., Grant S. G., Bliss T. V., Wolfer D. P., Kuhl D. (2006). Arc/Arg3.1 is essential for the consolidation of synaptic plasticity and memories. Neuron 52, 437–444 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posern G., Miralles F., Guettler S., Treisman R. (2004). Mutant actins that stabilise F-actin use distinct mechanisms to activate the SRF coactivator MAL. EMBO J. 23, 3973–3983 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posern G., Sotiropoulos A., Treisman R. (2002). Mutant actins demonstrate a role for unpolymerized actin in control of transcription by serum response factor. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4167–4178 10.1091/mbc.02-05-0068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posern G., Treisman R. (2006). Actin’ together: serum response factor, its cofactors and the link to signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 588–596 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G. (2008). c-Jun expression, activation and function in neural cell death, inflammation and repair. J. Neurochem. 107, 898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G., Behrens A. (2006). Role of the AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun in developing, adult and injured brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 78, 347–363 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G., Bohatschek M., Da Costa C., Iwata O., Galiano M., Hristova M., Nateri A. S., Makwana M., Riera-Sans L., Wolfer D. P., Lipp H. P., Aguzzi A., Wagner E. F., Behrens A. (2004). The AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun is required for efficient axonal regeneration. Neuron 43, 57–67 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanan N., Shen Y., Sarsfield S., Lemberger T., Schutz G., Linden D. J., Ginty D. D. (2005). SRF mediates activity-induced gene expression and synaptic plasticity but not neuronal viability. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 759–767 10.1038/nn1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley L. A., Bernstein J. J. (1996). Changes in dynamin and actin mRNA expression in the dorsal column-medial lemniscal system following dorsal column lesion. J. Neurosci. Res. 44, 47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G. A. (1995). Axotomy-induced regulation of c-Jun expression in regenerating rat retinal ganglion cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 30, 61–69 10.1016/0169-328X(94)00277-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom J., Heiduschka P., Beck S. C., Philippar U., Seeliger M. W., Schraermeyer U., Nordheim A. (2011). Degeneration of the mouse retina upon dysregulated activity of serum response factor. Mol. Vis. 17, 1110–1127 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A., Zhang M., Liu S. H., Sarkar S., Brunicardi F. C., Berger D. H., Belaguli N. S. (2011). Serum response factor expression is enriched in pancreatic {beta} cells and regulates insulin gene expression. FASEB J. 25, 2592–2603 10.1096/fj.10-173757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj A., Prywes R. (2004). Expression profiling of serum inducible genes identifies a subset of SRF target genes that are MKL dependent. BMC Mol. Biol. 5, 13. 10.1186/1471-2199-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgambato V., Vanhoutte P., Pages C., Rogard M., Hipskind R., Besson M. J., Caboche J. (1998). In vivo expression and regulation of Elk-1, a target of the extracellular-regulated kinase signaling pathway, in the adult rat brain. J. Neurosci. 18, 214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Callahan L. M., Sul J. Y., Kim T. K., Barrett L., Kim M., Powers J. M., Federoff H., Eberwine J. (2010). A neurotoxic phosphoform of Elk-1 associates with inclusions from multiple neurodegenerative diseases. PLoS ONE 5, e9002. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrocks A. D. (2001). The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 827–837 10.1038/35099076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P. E., Saxton J. (2003). Ternary complex factors: prime nuclear targets for mitogen-activated protein kinases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35, 1210–1226 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00031-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J. D., Bear M. F. (2011). New views of Arc, a master regulator of synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 279–284 10.1038/nn.2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota J., Ishikawa M., Sakagami H., Tsuda M., Baraban J. M., Tabuchi A. (2006). Developmental expression of the SRF co-activator MAL in brain: role in regulating dendritic morphology. J. Neurochem. 98, 1778–1788 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Hicks C., Xiao B., Deng R., Ji Y., Zhao X., Shepherd J. D., Posern G., Kuhl D., Huganir R. L., Ginty D. D., Worley P. F., Linden D. J. (2010). SRF binding to SRE 6.9 in the Arc promoter is essential for LTD in cultured Purkinje cells. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1082–1089 10.1038/nn.2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern S., Debre E., Stritt C., Berger J., Posern G., Knoll B. (2009). A nuclear actin function regulates neuronal motility by serum response factor-dependent gene transcription. J. Neurosci. 29, 4512–4518 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritt C., Knoll B. (2010). Serum response factor regulates hippocampal lamination and dendrite development and is connected with reelin signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1828–1837 10.1128/MCB.01434-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritt C., Stern S., Harting K., Manke T., Sinske D., Schwarz H., Vingron M., Nordheim A., Knoll B. (2009). Paracrine control of oligodendrocyte differentiation by SRF-directed neuronal gene expression. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 418–427 10.1038/nn.2280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Battle M. A., Misra R. P., Duncan S. A. (2009). Hepatocyte expression of serum response factor is essential for liver function, hepatocyte proliferation and survival, and postnatal body growth in mice. Hepatology 49, 1645–1654 10.1002/hep.22834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q., Chen G., Streb J. W., Long X., Yang Y., Stoeckert C. J., Jr., Miano J. M. (2006). Defining the mammalian CArGome. Genome Res. 16, 197–207 10.1101/gr.5210006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung Y. J., Walters E. T., Ambron R. T. (2004). A neuronal isoform of protein kinase G couples mitogen-activated protein kinase nuclear import to axotomy-induced long-term hyperexcitability in Aplysia sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 7583–7595 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1445-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi A., Estevez M., Henderson J. A., Marx R., Shiota J., Nakano H., Baraban J. M. (2005). Nuclear translocation of the SRF co-activator MAL in cortical neurons: role of RhoA signalling. J. Neurochem. 94, 169–180 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahirovic S., Bradke F. (2009). Neuronal polarity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a001644. 10.1101/cshperspect.a001644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff W., Alexander S. W., Miller F. D., Bisby M. A. (1991). Response of facial and rubrospinal neurons to axotomy: changes in mRNA expression for cytoskeletal proteins and GAP-43. J. Neurosci. 11, 2528–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff W., Bisby M. A. (1990). Cytoskeletal protein synthesis and regulation of nerve regeneration in PNS and CNS neurons of the rat. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 1, 189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff W., Bisby M. A., Kreutzberg G. W. (1988). Changes in cytoskeletal proteins in the rat facial nucleus following axotomy. J. Neurosci. 8, 3181–3189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M. J., Roe M. W., Malik R. K., Blackshear P. J. (1994). Insulin and other growth factors induce binding of the ternary complex and a novel protein complex to the c-fos serum response element. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21127–21135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte P., Nissen J. L., Brugg B., Gaspera B. D., Besson M. J., Hipskind R. A., Caboche J. (2001). Opposing roles of Elk-1 and its brain-specific isoform, short Elk-1, in nerve growth factor-induced PC12 differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5189–5196 10.1074/jbc.M006678200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen M. K., Guettler S., Larijani B., Treisman R. (2007). Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science 316, 1749–1752 10.1126/science.1141084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialou V., Maze I., Renthal W., Laplant Q. C., Watts E. L., Mouzon E., Ghose S., Tamminga C. A., Nestler E. J. (2010). Serum response factor promotes resilience to chronic social stress through the induction of DeltaFosB. J. Neurosci. 30, 14585–14592 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2496-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wang D. Z., Hockemeyer D., Mcanally J., Nordheim A., Olson E. N. (2004). Myocardin and ternary complex factors compete for SRF to control smooth muscle gene expression. Nature 428, 185–189 10.1038/nature02516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner A., Willem M., Jones L. L., Kreutzberg G. W., Mayer U., Raivich G. (2000). Impaired axonal regeneration in alpha7 integrin-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 20, 1822–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe S. R., Alvania R. S., Ramanan N., Wood J. N., Mandai K., Ginty D. D. (2008). Serum response factor mediates NGF-dependent target innervation by embryonic drg sensory neurons. Neuron 58, 532–545 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebel F. F., Rennekampff V., Vintersten K., Nordheim A. (2002). Generation of mice carrying conditional knockout alleles for the transcription factor SRF. Genesis 32, 124–126 10.1002/gene.10049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D., Li K. W., Zheng J. Q., Chang J. H., Smit A., Kelly T., Merianda T. T., Sylvester J., Van Minnen J., Twiss J. L. (2005). Differential transport and local translation of cytoskeletal, injury-response, and neurodegeneration protein mRNAs in axons. J. Neurosci. 25, 778–791 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiu G., He Z. (2006). Glial inhibition of CNS axon regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 617–627 10.1038/nrm1941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]