Abstract

Longitudinal relations between past suicidality and subsequent changes in psychological distress at follow-up were examined among gay, lesbian, and bisexual (GLB) youths, as were psychosocial factors (e.g., self-esteem, social support, negative social relationships) that might mediate or moderate this relation. Past suicide attempters were found to have higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, and conduct problems at a later time than youths who neither attempted nor ideated. Psychosocial factors failed to mediate this relation. The interaction among past suicidality, social support, and negative relationships was associated with subsequent changes in all three psychological distress indicators six months later. Specifically, high levels of support (either from family or friends) or negative relationships were found to predict increased psychological distress among those with a history of suicide attempts, but not among youths without a history of suicidality. The findings suggest that GLB youths who attempt suicide continue to have elevated levels of psychological distress long after their attempt and they highlight the importance of social relationships in the youths’ psychological distress at follow-up.

Keywords: gay, lesbian, bisexual adolescents, suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, psychological distress, conduct problems, self-esteem, social support, negative social relationships, longitudinal research

Suicide is a critical public health concern among gay, lesbian, and bisexual (GLB) youths. These youths live in a society that stigmatizes and condemns homosexuality (e.g., Herek, 2000). Thus, it is unsurprising that many GLB youths, given their young age and developmentally limited coping strategies, have considered or attempted suicide in response to the stigmatization (e.g., Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995). Indeed, the prevalence of suicidality is elevated among GLB youths (see below). However, nothing is known about the long-term implications of suicidality among GLB youths. The present report on GLB youths examines the relation of suicidality on subsequent psychological distress at follow-up and further investigates psychosocial factors that mediate or moderate the relation between suicidality and changes in psychological distress.

Prevalence of Suicidality Among GLB Youths

Studies employing representative samples have found a significantly higher prevalence of suicide attempts among GLB youths than heterosexual youths: between 21% and 35% within the past year among GLB youths and between 4% and 14% among heterosexual youths (Faulkner & Cranston, 1998; Fergusson et al., 1999; Garofalo et al., 1999; Remafedi et al., 1998). Similarly, the prevalence of suicidal ideation is higher among representative samples of GLB youths (31% – 68%) than among their heterosexual peers (20% –29%; Faulkner & Cranston, 1998; Fergusson et al., 1999; Remafedi et al., 1998).

Suicidality and Psychological Distress at Follow-Up

The suicidality literature has focused primarily on the etiologic role of psychological distress on suicidality, but much less on the long-term adjustment of suicide attempters (Spirito et al., 2000; Boergers & Spirito, 2003). Youths who attempt or contemplate suicide would be expected to have high levels of psychological distress following their suicidality. Empirical data on heterosexual youths support this hypothesis (e.g., Laurent et al., 1998; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Pfeffer et al., 1993; Spirito et al., 1992). For example, in a large cohort of adolescents (Fergusson & Lynskey, 1995), youths who reported a past suicide attempt (at or prior to age 14) were 17 times more likely to be diagnosed (at age 16) with a mood disorder, 5 times more likely to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, and 13 times more likely to be diagnosed with conduct disorder. In addition, a follow-up study of adolescent suicide attempters found that 55% had the same or worse psychosocial functioning 11 years post-attempt (Granboulan et al., 1995).

If we can generalize from heterosexual youths to GLB youths, we would expect that GLB youths who attempt suicide would have high levels of psychological distress for some time following their suicidality. Among GLB youths, significant relations have been found between suicidality and psychological distress (e.g., Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). However, these data have been cross-sectional. Longitudinal data are required to examine the hypothesis that suicidality is associated with subsequent psychological distress. Furthermore, because past psychological distress may be the cause of both suicidality and subsequent psychological distress, research must account for earlier distress when investigating whether suicidality has long-term implications for subsequent distress. The present report addresses the association of suicidality with changes in psychological distress over time by controlling for earlier distress.

Mediational Hypothesis: Psychosocial Factors

If a relation exists between past suicidality and psychological distress at follow-up, as we hypothesize, it would be important to examine factors that explain (i.e., mediate) the relation, given that the mediators could be targeted by interventions designed to ameliorate the effects of suicidality. Potential mediators of the relation between suicidality and subsequent psychological distress include both individual resources (i.e., self-esteem) and social relationship characteristics (i.e., social support and negative social relationships).1 Lower levels of self-esteem and social support have been related both to higher prevalence of suicidality and greater psychological distress among heterosexual youths (Fergusson & Lynskey, 1995; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Overholser et al., 1995; Roberts et al., 1998; Shagle & Barber, 1993; Wichstrom, 2000) and among GLB youths (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Hershberger et al., 1997; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). Negative social relationships have been associated with suicidality among heterosexual (Beautrais et al., 1996; Shagle & Barber, 1993; Smith & Anderson, 2000) and GLB youths (D’Augelli et al., 2001). However, the research has not examined whether psychosocial factors explain the relation between suicidality and subsequent psychological distress among GLB youths. We respond to this oversight and hypothesize that lower self-esteem or social support and more negative social relationships mediate the associations of suicidality with subsequent changes in distress. We also add that if over-reporting of suicide attempts or other self-presentation effects explain the high rates of suicidality among GLB youths (Savin-Williams, 2001), social desirability should mediate the relation of suicidality with subsequent distress.

Moderating Hypothesis: Social Relationships by Suicidality

Alternatively, suicidality may be associated with subsequent changes in psychological distress for some GLB youths, such as for youths with low social support, but not for all GLB youths. Social resources (e.g., social support) have been found to moderate (i.e., interact with) the relation between stress and distress (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Wills & Fegan, 2001). Similarly, social resources may moderate the association of suicidality with psychological distress, such that individuals with a history of suicide attempts and low levels of social resources may be most at risk for subsequent psychological distress. Furthermore, negative social relationships may limit the ability of social resources to protect against the long-term relation between suicidality and distress, such that suicidality is related to subsequent psychological distress only for those individuals with few social supports and high levels of negative relationships. Negative social relationships have been found to limit the benefits of social support, with supportive relationships promoting psychological well-being only for individuals without negative social relationships (Siegel et al., 1997). Similar results have been found among GLB youths (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995). Although extant research on GLB youths has not examined the psychosocial conditions (i.e., moderating effects) under which past suicidality may be associated with subsequent distress, we hypothesize that the relation between suicidality and subsequent changes in psychological distress is moderated by social supports and negative social relationships.

This report is the first to examine the longitudinal relation of past suicidality to subsequent changes in psychological distress at follow-up among GLB youths. Further, it investigates the role of psychosocial resources as mediators or moderators of the relation between suicidality and subsequent changes in psychological distress.

Method

Participants

Youths between the ages of 14 – 21 years were recruited from three gay-focused community organizations (85%) and two public-college GLB student organizations (15%) in New York City. Approximately 80% of the youths approached for recruitment participated in the study.

Of 164 youths interviewed at baseline, 8 were excluded due to their ineligibility for the study, resulting in a final sample of 80 males and 76 females. The mean age was 18.3 years (SD = 1.65). The youths were of Latino (37%), Black (35%), White (22%), Asian (5%) or other ethnic backgrounds (2%). Thirty-four percent (34%) of the youths indicated that their mother or father received welfare, food stamps, or Medicaid. The youths self-identified as gay/lesbian (66%), bisexual (31%), or other (3%, e.g., “free spirit”).

Procedure

All youths provided voluntary and signed informed consent. Parental consent was waived by the Commissioner of Mental Health for New York State for those youths who were under age 18. An adult at each CBO served in loco parentis to safeguard the rights of each minor-aged participant. The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board and it received a federal certificate of confidentiality.

Youths participated in a structured interview, with follow-up interviews 6 and 12 months after the baseline interview. Baseline interviews took place in 1993–1994, with follow-up interviews conducted through 1995. Of the youths, 92% (143/156) were re-interviewed at 6 months and 90% (140/156) at 12 months. Overall, 85% of the youths were interviewed at all 3 assessment periods. Youths received $30 for participating in each of the 3 interviews.

Measures

Suicidality

The prevalence of lifetime suicide attempts was assessed at baseline by asking youths, “Have you ever hurt yourself or tried to kill yourself at any time in your life?” The prevalence of lifetime suicide ideation was assessed by asking youths, “Have you ever seriously thought about killing yourself? By ‘seriously,’ I mean every day for a week or more.” These items, developed by Shaffer and Gould (1986), were employed previously in another study of gay and bisexual male youths (Rotheram-Borus et al., 1994) and they were found to detect rates of suicide attempts and ideation within the range identified by probability samples of GLB youths. To increase validity of the assessment, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was assessed prior to the assessment of suicide attempts. Youths reporting suicidality were queried about the frequency of attempts/ideation, age at first attempt/ideation, method of most recent attempt, and whether they received medical treatment following their attempt. Suicidality was not assessed at the 6- and 12-month time periods.

Psychological Distress

Depressive and anxious symptoms during the past week were assessed by means of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, 1993) at the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month assessments using a Likert-type response scale from “not at all” (0) to “extremely” (4) distressing. The mean of each subscale was computed, with high scores indicating elevated distress. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) across the three assessments ranged from .80 to .82 for anxious symptoms and from .81 to .83 for depressive symptoms. The BSI has been validated among adolescent samples (Derogatis, 1993).

Conduct Problems

As the BSI assesses only internalized distress, we included conduct problems to assess externalized distress. A 13-item index was created to assess conduct problems experienced by the youths, such as skipping school, vandalism, stealing, fighting, and running away. Items were constructed using the conduct problems identified in DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). Our measure of conduct problems, a count of the problems endorsed by the youths, has been used previously with heterosexual youths (Wichstrom, 2000) and gay and bisexual male youths (Rotheram-Borus et al., 1995).

Self-Esteem

Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item scale was administered at baseline, with its four-point Likert response scale ranging from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (4). The mean was computed, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem (Cronbach’s α = .86). This measure of self-esteem has been used with other samples of GLB youths (e.g., Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Rosario et al. 1996).

Social Support from Family and Friends

Procidano and Heller’s (1983) measures of perceived social support from family and from friends were adapted, deleting items that might be confounded with psychological health. The two resulting 12-item measures, administered at baseline using a yes (1) or no (0) response format, assessed the extent to which needs for support, information, and feedback were met by family and by friends (e.g., “I rely on my [family/friends] for emotional support”). A count of the items endorsed was used as an index of social support from family (Cronbach’s α = .90) and friends (Cronbach’s α = .80). The measure was originally validated on late adolescents (Procidano & Heller, 1983).

Negative Social Relationships

The 12-item Social Obstruction Scale (SOS: Gurley, 1990) was administered at baseline to assess the presence of negative social relationships with others, including being treated poorly, being ignored, and being manipulated by others (e.g., “Somebody treats me as if I were nobody”). Items use a four-point response scale ranging from “definitely false” (1) to “definitely true” (4). The mean score was computed with higher scores indicating greater levels of negative social relationships (Cronbach’s α = .85). Negative relationships were only moderately correlated with friend and family support (r’s = −.18, −.33, respectively). Not all negative relationships experienced by GLB youths are due to their homosexuality. The SOS assesses negative relationships in general, regardless of the cause; it is not specifically a measure of negative reactions from others to the youths’ homosexuality. The relations of such stigmatizing reactions to psychological distress were examined elsewhere (Rosario et al., 2002).

Social Desirability

The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1964) was self-administered at baseline. Two items, considered inappropriate for youths, were removed, resulting in a 31-item scale, using a true-false response format. Factor analysis revealed that 12 items loaded on a single factor. A count of the 12 items was computed as the indicator of social desirability (Cronbach’s α = .74). A similarly reduced version of the Marlowe-Crowne measure was used elsewhere with GLB and heterosexual youths (Safren & Heimberg, 1999).

Results

Suicidality Among the GLB Youths

Of the 156 youths interviewed at baseline, 35% had attempted suicide, 23% had seriously thought about suicide but had not attempted, and 42% had neither attempted nor ideated at any time in their lives. Of the youths who had attempted suicide, many had attempted more than once (M = 3.76, SD = 7.56). The last of these attempts was an average of 3.16 years (SD = 2.88) before the baseline assessment, with 31% having attempted suicide in the year prior to the study. The youths were an average of 15.28 years of age (SD = 2.86) at their most recent suicide attempt. Of the 79 youths who had ever seriously thought about suicide (43 had both ideated and attempted suicide and 36 had ideated but never attempted suicide), 39% reported one or two episodes of ideation, 35% reported between three and ten episodes, and 26% had more than 10 episodes of suicidal ideation. The youths’ last suicidal ideation had occurred an average of 1.87 years ago (SD = 2.05), with 53% having an episode of ideation within the year prior to the study. The youths were an average of 16.49 years of age (SD = 2.35) at the time of their most recent suicidal ideation.

The suicide attempts of the youths were serious. Of the 55 youths who reported suicide attempts, 93% reported a specific method for their most recent attempt, including cutting (32%), ingesting pills or chemicals (65%), jumping (8%), or some other method (16%). Further, 51% reported that their suicide attempt required medical care, including 33% who were hospitalized. GLB youths who received medical care for their attempt did not differ significantly from those who did not receive care on any study variable, including psychological distress and social desirability. Interestingly, social desirability was unrelated to suicidality, further suggesting that this sample of GLB youths accurately reported their history of suicidality.

Mean Differences Between Suicidal and Nonsuicidal Youths

Among the GLB youths who had attempted suicide (n = 55), those who only had ideated (n = 36), and those who had neither attempted nor ideated (n = 65), several significant differences emerged with respect to subsequent psychological distress and psychosocial factors (see Table 1). Youths who had attempted reported more depressive symptoms at baseline, more anxious symptoms at the baseline and 6-month assessments, and more conduct problems at the 12-month assessment than did youths who had neither attempted nor ideated. Similarly, youths who only had ideated, but never attempted, reported more depressive symptoms at the baseline and 12-month assessments and more anxious symptoms at baseline than youths who had neither attempted nor ideated. Youths who reported past suicide attempts, as compared with non-suicidal youths, consistently reported fewer psychosocial resources (i.e., self-esteem and family and friend social supports) and more negative social relationships.

Table 1.

Mean Comparison of Psychological Distress and Psychosocial Factors by History of Suicidality.

| Assessment Period | Attempt | Past Suicide Only | Past Ideation Neither | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F (df) | |

| Baseline: | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.33 (0.93)a | 1.24 (0.84)a | 0.77 (0.72)b | 7.69** (2, 153) |

| Anxious Symptoms | 1.38 (0.92)a | 1.48 (1.01)a | 0.94 (0.78)b | 5.61** (2,153) |

| Conduct Problems | 2.24 (1.40) | 1.69 (1.09) | 1.71 (1.89) | 2.07 (2, 153) |

| Self-esteem | 3.20 (0.53)a | 3.25 (0.50)a | 3.50 (0.45)b | 6.07** (2, 153) |

| Social Support - Family | 5.49 (3.86)a | 5.89 (4.18) | 7.28 (3.99)b | 3.27* (2, 153) |

| Social Support - Friends | 9.60 (2.65)a | 10.00 (2.31) | 10.65 (2.03)b | 3.08* (2, 153) |

| Negative Social Relationships | 2.39 (0.67)a | 2.17 (0.70) | 1.96 (0.69)b | 5.69** (2, 152) |

| Social Desirability | 5.96 (2.87) | 5.42 (2.29) | 6.31 (2.97) | 1.18 (2, 153) |

| Six Months: | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.06 (0.96) | 0.91 (0.78) | 0.73 (0.62) | 2.34 (2, 140) |

| Anxious Symptoms | 1.23 (0.92)a | 0.96 (0.72) | 0.69 (0.77)b | 6.10** (2, 140) |

| Conduct Problems | 1.57 (1.45) | 1.41 (1.41) | 1.35 (1.39) | 0.34 (2, 140) |

| Twelve Months: | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.76 (0.76) | 1.01 (0.85)a | 0.57 (0.62)b | 4.00* (2, 137) |

| Anxious Symptoms | 0.81 (0.82) | 0.90 (0.76) | 0.60 (0.63) | 1.97 (2, 137) |

| Conduct Problems | 1.82 (1.56)a | 0.97 (1.04)b | 1.13 (1.09)b | 5.83** (2, 137) |

Note: The “attempt” group included youths with a history of suicide attempt or a history of both suicide attempt and ideation. Significant (p <.05) pairwise differences, using Fisher’s protected t test, were found among means with differing superscripts.

p < .05

p < .01.

Change in Psychological Distress Over Time

Repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine whether the level of psychological distress changed over time. Changes were found in depressive symptoms, F (2, 128) = 10.65, p < .001, anxious symptoms, F (2, 128) = 21.62, p < .001, and conduct problems, F (2, 128) = 5.93, p < .01. Post hoc comparisons revealed significant (p < .05) decreases over time. Specifically, depressive symptoms decreased between the baseline (M = 1.23) and 6-month (M = 0.87) assessments, but not between the 6- and 12-month (M = 0.76) assessments. Anxious symptoms decreased between the baseline (M = 1.29) and 6-month (M = 0.96) assessments and between the 6- and 12-month (M = 0.78) assessments. Finally, conduct problems significantly decreased between the baseline (M = 1.80) and 6-month assessments (M = 1.45), but not between the 6- and 12-month (M = 1.34) assessments.

Correlations of Psychosocial Resources with Psychological Distress

The relations between psychological distress and psychosocial factors are presented in Table 2. Lower self-esteem was correlated with more depressive and anxious symptoms at all 3 assessments and with more conduct problems at baseline. More social support from friends and family was associated with fewer depressive symptoms at baseline and 12-month assessments and with fewer conduct problems at the 12-month assessment. More negative social relationships were related consistently to more depressive and anxious symptoms and to more conduct problems at each assessment. More socially desirable responses were correlated with fewer depressive symptoms at all assessments, fewer anxious symptoms at the 12-month assessment, and fewer conduct problems at the baseline and 6-month assessments.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Assessment: | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Depressive Symptoms | — | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Anxious Symptoms | .56* | — | |||||||||||||

| 3. Conduct Problems | .25* | .28* | — | ||||||||||||

| 4. Self-Esteem | −.62* | −.35* | −.16* | — | |||||||||||

| 5. Social Support - Friends | −.35* | −.13 | −.15 | .28* | — | ||||||||||

| 6. Social Support - Family | −.23* | −.07 | −.11 | .27* | .29* | — | |||||||||

| 7. Negative Social Relationships | .43* | .36* | .23* | −.44* | −.18* | −.33* | — | ||||||||

| 8. Social Desirability | −.23* | −.15 | −.29* | .25* | −.04 | .15 | −.20* | — | |||||||

| Six-Month Assessment: | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Depressive Symptoms | .35* | .23* | .20* | −.54* | −.10 | −.07 | .34* | −.20* | — | ||||||

| 10. Anxious Symptoms | .33* | .54* | .23* | −28* | −.03 | −.05 | .39* | −.16 | .73* | — | |||||

| 11. Conduct Problems | .17* | .08 | .44* | −.10 | .02 | −.16 | .24* | −.25* | .29* | .22* | — | ||||

| Twelve-Month Assessment: | |||||||||||||||

| 12. Depressive Symptoms | .33* | .28* | .14 | −.37* | −.20* | −.26* | .30* | −.22* | .56* | .49* | .23* | — | |||

| 13. Anxious Symptoms | .31* | .48* | .19* | −.23* | −.11 | −.12 | .28* | −.20* | .51* | .66* | .13 | .63* | — | ||

| 14. Conduct Problems | .15 | .13 | .34 | −.02 | −.19* | −.12 | .24* | −.15 | .15 | .21* | .41* | .20* | .25* | — | |

p < .05.

Association of Sociodemographic Variables with Study Variables

Potential demographic covariates were examined for their relation to past suicidality, psychological distress, and psychosocial factors. Comparisons between youths who reported suicide attempts, those who only reported suicidal ideation, and those who reported neither past suicide attempts nor ideation indicated no significant differences in gender, age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or recruitment site. No significant relations were noted between any of the potential demographic covariates and any indicator of psychological distress at any of the 3 assessment periods. However, several significant (p < .05) relations emerged between the potential covariates and the psychosocial factors, indicating the need to control for gender and ethnicity in the mediating and moderating analyses. Female youths reported more social desirability than male youths (r = .16). Black, Latino, White, and Asian/Other youths differed on self-esteem, F (3, 152) = 2.56, p < .06, and social support from family, F (3, 152) = 3.66. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that Black youths reported significantly lower self-esteem than did Latino youths. Moreover, Black and Asian/Other youths reported less social support from family than did Latino or White youths.

Multivariate Association of Suicidality with Subsequent Distress and Change In Distress

Multiple regression was used to examine the unique relations between suicidality and both subsequent psychological distress (i.e, without controlling for baseline distress) and changes in psychological distress (i.e., controlling for baseline distress). As hypothesized, past suicidality was significantly associated with increased subsequent distress in 4 of 6 six possible outcomes, uniquely explaining between 3 – 8% of the variance in subsequent psychological distress. Specifically, past suicide attempt was associated with more depression (β = .20) and anxiety (β = .31) at the 6-month assessment and with more conduct problems (β = .25) at 12 months. Additionally, suicidal ideation was associated with more depressive symptoms (β = .25) at 12 months.

After controlling for baseline depressive and anxious symptoms, as well as conduct problems, a history of suicide attempts was significantly associated with increased psychological distress for 3 of 6 possible outcomes. Specifically, past suicide attempts predicted an increase in anxious symptoms (β = .19) between baseline and 6-month assessments and an increase in conduct problems (β = .19) between baseline and 12-month assessments. Additionally, past suicidal ideation was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms (β = .17, p < .06) between baseline and 12-month assessments. Past suicidality uniquely explained between 3 – 5% of the change in these psychological distress outcomes.

Mediating Role of Psychosocial Factors

To examine whether psychosocial factors explained the significant relations identified between suicidality and subsequent changes in psychological distress, following the demographic controls (i.e., gender and ethnicity), psychosocial factors (i.e., self-esteem, family support, friend support, and negative social relationships) and social desirability were entered into the regression model prior to the entry of past suicidality (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Imposing controls for psychosocial factors and social desirability did not alter the relation between suicidality and change in psychological distress. Thus, psychosocial factors and social desirability failed to mediate the relation between suicidality and changes in distress.

Moderating Role of Social Relationships

Hierarchical regression was used to examine the potential three-way interactions among suicide attempts, social support, and negative social relationships, after controlling for gender, ethnicity, baseline psychological distress, psychosocial factors, and past suicidality. Interactions between suicidal ideation and social relationships were not examined because a small number of youths reported only suicidal ideation. As recommended by Cohen & Cohen (1983), continuous variables were mean-centered prior to computing the interaction terms and all possible two-way interactions were entered into the regression prior to the entry of the three-way interactions.

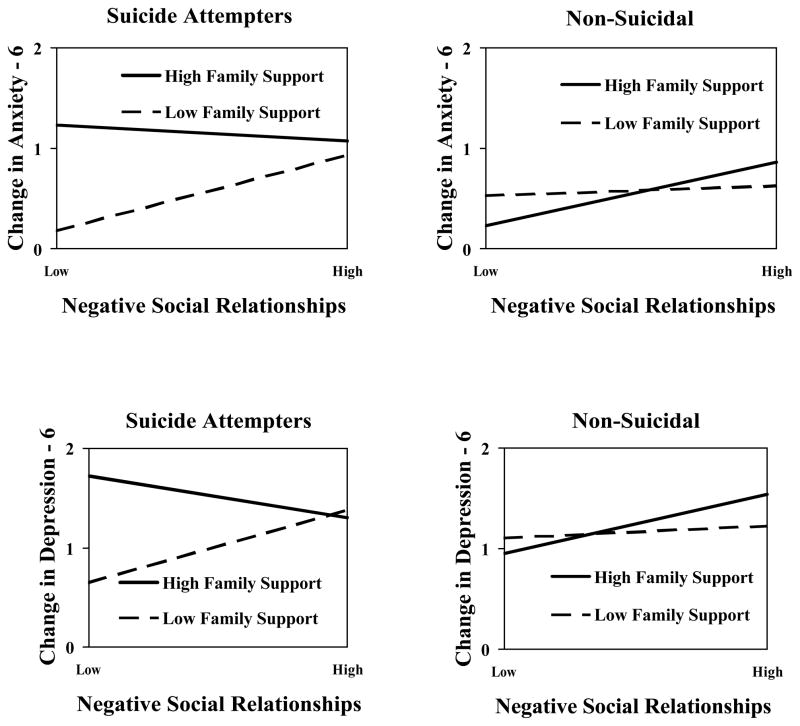

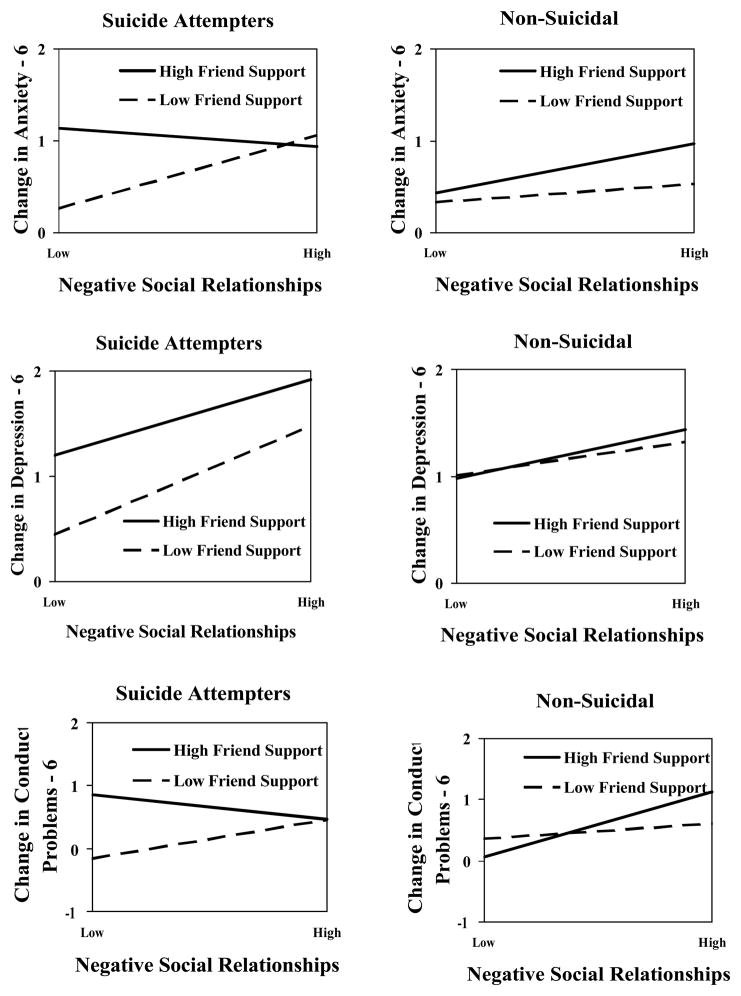

Five of 6 three-way interactions significantly predicted change in psychological distress between the baseline and 6-month assessments (see Table 3). The three-way interaction among suicide attempt, family support, and negative social relationships significantly predicted changes in depressive and anxious symptoms between the baseline and 6-month assessments. Similarly, the three-way interaction among suicide attempts, friend support, and negative social relationships significantly predicted changes in depressive and anxious symptoms and in conduct problems at 6 months. Together, these significant interactions explained 10% of the variance in the change in depressive symptoms, 6% of change in anxious symptoms, and 3% of change in conduct problems.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Predicting Change in Psychological Distress.

| Six-Month Assessment

|

Twelve-Month Assessment

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Conduct | Depression | Anxiety | Conduct | |

| Step 1: Main Effects | ||||||

| Suicide Attempt | .06 | .17* | −.02 | −.06 | −.01 | .18+ |

| Suicidal Ideation | .02 | .01 | .01 | .14 | .03 | −.09 |

| Self-Esteem | −.14 | −.05 | .09 | −.17 | −.03 | .22* |

| Family Support | .10 | .08 | −.09 | −.12 | −.05 | −.02 |

| Friend Support | .02 | .07 | .13 | −.08 | −.03 | −.14 |

| Negative Social Relationships | .20* | .21** | .16 | .11 | .07 | .17 |

| Social Desirability | −.08 | −.04 | −.09 | −.12 | −.10 | −.08 |

| Step 2: Two-way interactions | ||||||

| Attempt x Family Support | .12 | .18 | −.15 | .02 | −.08 | .06 |

| Attempt x Friend Support | .13 | −.03 | −.01 | .20 | .11 | −.01 |

| Attempt x Neg. Relationships | .03 | .05 | −.05 | −.05 | .07 | .30** |

| Neg. Relationships x Family Support | .10 | .10 | −.03 | −.02 | .04 | −.17* |

| Neg. Relationships x Friend Support | −.10 | −.00 | .08 | −.11 | .03 | .14 |

| Friend Support x Family Support | .11 | .17* | −.14 | −.03 | .10 | −.13 |

| Step 3: Three-way interactions | ||||||

| Attempt x Neg. Rel. x Family Support | −.25* | −.21* | −.07 | −.01 | −.16 | −.06 |

| Attempt x Neg. Rel. x Friend Support | −.37** | −.24* | −.23* | −.12 | −.10 | −.18 |

| Model R2 | .34** | .49** | .35** | .29** | .30** | .38** |

Note: Depression = depressive symptoms, Anxiety = anxious symptoms, Conduct = conduct problems, Neg. Relationships = Neg. Rel. = negative social relationships. Standardized β coefficients are presented. Controls for gender, ethnicity, and baseline psychological distress were imposed in all regression analyses. Model R2 includes demographic controls, baseline psychological distress, past suicidality, hypothesized mediators, and the interactions.

p < .06,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Plots of each significant three-way interaction are presented as a pair of side-by-side graphs representing the relation between supportive and negative relationships for youths who attempted suicide and for non-suicidal youths. Figure 1 depicts the interactions involving family support and Figure 2 depicts the interactions involving friend support. The interactions indicated a similar pattern of relations, regardless of the source of support. Social support and negative social relationships functioned differently for youths with past suicide attempts as compared with youths who had never considered suicide. Specifically, among those who attempted suicide, youths with low levels of family or friend social support and low levels of negative relationships were found to have the least change in psychological distress between the baseline and 6-month assessments. Youths with high levels of social support and/or high levels of negative social relationships reported the greatest increase in psychological distress over time. In contrast, among youths who never considered suicide, there was little or no change in psychological distress regardless of level of social support or negative relationships.

Figure 1.

Significant three-way interaction of suicide attempt by family support by negative social relationships predicting changes in psychological distress. Plots of each significant three-way interaction are presented as a pair of side-by-side graphs representing the relation for suicidal youths and the relation for non-suicidal youths.

Figure 2.

Significant three-way interaction of suicide attempt by friend support by negative social relationships predicting changes in psychological distress. Plots of each significant three-way interaction are presented as a pair of side-by-side graphs representing the relation for suicidal youths and the relation for non-suicidal youths.

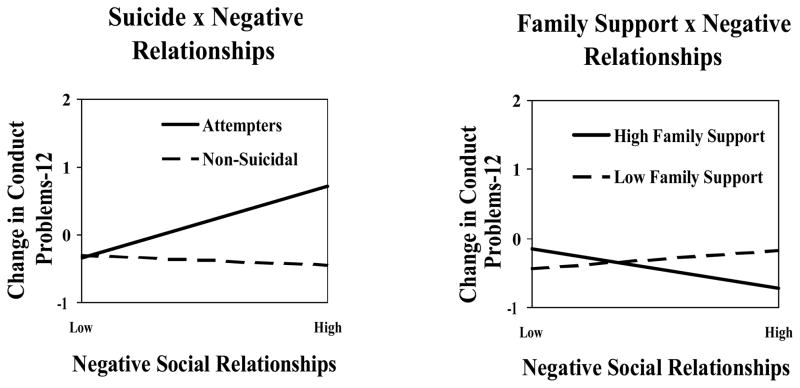

In addition to the three-way interactions, two significant two-way interactions were found to predict changes in conduct problems between the baseline and 12-month assessments (see Figure 3). The interaction of suicide by negative relationships indicated that among youths who had attempted suicide, high levels of negative relationships were associated with increased conduct problems. However, among youths who had never considered suicide, negative relationships had little to do with changes in conduct problems. The family support by negative relationships interaction indicated that high levels of family support were associated with decreased conduct problems for youths with high levels of negative relationships.

Figure 3.

Significant two-way interactions predicting change in conduct problems.

Discussion

Suicidality and Subsequent Psychological Distress

We examined the role of suicidality on long-term psychological distress among GLB youths, given the clinical importance but absence of such information in the literature. As expected, youths who had attempted suicide subsequently reported in 5 of 9 possible relations more depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, and conduct problems than youths who had neither attempted suicide nor ideated. Even after controlling for earlier psychological distress, past suicide attempts remained associated with increased anxious symptoms and conduct problems.

We also examined whether psychosocial factors might explain (i.e., mediate) the associations found between past suicidality and subsequent changes in psychological distress. Youths who attempted suicide subsequently reported fewer psychosocial resources (self-esteem and social support) and more negative social relationships than youths who neither attempted nor ideated. Further, baseline psychosocial resources were correlated with subsequent psychological distress. However, psychosocial factors failed to mediate the relation between past suicide attempts and changes in psychological distress.

The moderating hypothesis was supported by the presence of 5 of 6 significant three-way interactions among suicide attempts, social support, and negative social relationships predicting subsequent changes in depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, and conduct problems between the baseline and 6-month assessments. Among youths with a history of suicide attempts, high levels of negative relationships and/or high levels of social support were associated with increased psychological distress at follow-up. These findings were surprising because, according to the social support literature (e.g., Cohen & Wills, 1985), low levels of social support should be associated with adverse outcomes. Further, the findings indicated that among suicidal youths, the smallest increase in psychological distress was found among those youths with low levels of both negative relationships and social support. In contrast, among non-suicidal youths, the interaction of negative relationships and supportive relationships with family and friends had little relation to psychological distress over time. Indeed, for the non-suicidal youths, peer support was negatively correlated and negative social relationships were positively correlated with subsequent psychological distress, as would be expected in the larger social support literature. Thus, the significant interactions suggest that social relationships function differently for GLB youths with a history of suicide attempts as compared with non-suicidal GLB youths.

The interactions found here inform our understanding of the social relationships of GLB youths. Supportive and unsupportive relationships co-exist. Regardless of the supportiveness of family and friends, GLB youths may experience degrading and belittling relationships with members of their social networks, possibly with the same family and friends who provide support. Persons who care and love the youth may respond negatively, even violently, to the youth upon learning about his or her GLB status (D’Augelli et al., 1998; Rosario et al., 1996). Indeed, this interpretation is supported indirectly by Schneider and colleagues (1989) who found that gay and bisexual male youths who attempted suicide were more likely than non-suicidal peers to rate individuals who rejected them as more important to them and as people on whom they depended. Thus, although initially counter-intuitive, our findings are understandable from the perspective of GLB youths. In addition, youths who attempt suicide, including GLB youths, are psychologically more vulnerable than youths who do not attempt. Consequently, attempting youths, as compared with non-suicidal youths, may be more sensitive to social interactions that might be negative or the attempting youths may perceive the same social interactions as more negative.

More broadly, our findings should alert the larger social support literature that there are conditions under which social support has no effects (as with our non-suicidal youths) and other conditions under which social support has negative implications, given the co-occurrence of negative social interactions. Research demonstrating the adverse effects of social support are not unprecedented. Reifman and Windle (1995) found that social support from friends was associated with greater suicidality among non-depressed adolescents. Among GLB youths, Hershberger & D’Augelli (1995) found a significant interaction between family support and victimization on psychological distress, indicating that while high levels of support were beneficial when the youths experienced little victimization, high and moderate levels of support were associated with higher levels of distress under conditions of high victimization.

Implications for Research

This report suggests the need for further research into the long-term psychological adjustment of GLB youths with a history of suicide attempts. The research on suicidality among GLB youths has focused exclusively on predictors of suicide attempts, without considering how youths who do attempt suicide fare in the future. Several questions remain regarding the long-term adjustment of GLB youths who attempt suicide, such as the magnitude and duration of relation between suicidality and subsequent psychological distress. Our findings suggest that suicide attempts continue to be related to youths’ distress for some time following the attempt. The importance of longitudinal data for understanding the long-term implications of suicidality for GLB youths cannot be overstated.

Future research also must consider two issues with respect to construct validity of suicidality among GLB youths. First, research has demonstrated relations between suicidality and same-sex sexuality (e.g., Garofalo et al., 1999; Remafedi et al., 1998), but it has not determined whether the suicide attempt was actually attributed to the young person’s sexuality. D’Augelli and colleagues (2001) found that 57% of suicidal GLB youths attributed their attempts to their sexual identity. Thus, future studies must consider the issue or situation that precipitates or motivates suicide attempt. Second, we must address whether reported suicide attempts are actual attempts. Savin-Williams (2001) found that 29% of reported attempts (10/34) among non-heterosexual female college students were “false” attempts because the youths ideated, planned, or had a method for attempting suicide, but did not actually attempt suicide. However, youths from the present study appear to accurately report suicide attempts because nearly all attempters were able to offer a potentially lethal method of how they attempted, the majority required medical attention for their attempt, and their reports of suicidality were unrelated to social desirability. Additional confidence in the validity of the attempt data may be attributed to ordering of items: We asked about suicidal ideation before questioning the youths about suicide attempts.

Implications for Therapeutic and Preventive Interventions

The distress findings strongly suggest the need for psychological intervention for GLB youths who have attempted suicide, and to a lesser extent, for those who only experienced suicidal ideation. The data indicate the importance of reducing the extent of negative social relationships for GLB youths who have attempted suicide. To counterbalance the negative social relationships, interventions must identify the sources and reasons underlying the problematic social relationships to determine what might be done. If the sources of the negative interactions are parents, therapeutic interventions with the family might be a way of altering the negative interactions, presuming the parents and youths agree to therapy. On the other hand, if the sources of the negative interactions are peers, it might be possible to substitute new social relationships with other peers by means of supportive environments at gay-focused organizations. Although, the youths in this report had been involved in any one of the gay-focused organizations for a maximum of approximately one year (M = 13.9 months, SD = 13.6), it is unclear whether enough time had past or actually been spent at the organizations to develop supportive peer networks, or whether the peer relationships developed at the organizations could actually counteract potential negative relationships with family or with other, presumably heterosexual peers in school, neighborhood, and other settings.

Despite the negative implication of the findings for GLB youths who have attempted suicide, we must note that the majority (65%) of youths sampled here reported never attempting suicide and 42% had never even seriously thought about attempting suicide. Indeed, the average depressive and anxious symptoms scores for the non-suicidal GLB youths (see Table 1) were generally below the adolescent norms for these measures (i.e., .82 and .78, respectively; Derogatis, 1993) across all three time periods. This comparison suggests that many GLB youths have been able to adjust well, despite the significant challenges they may confront. A possible reason for the lower distress was that the non-suicidal GLB youths had significantly higher levels of self-esteem, peer and family support, and lower levels of negative social relationships than youths who attempted suicide. In general, the findings suggest that GLB youths are a heterogeneous group with regard to suicidality, psychological distress, and psychosocial resources. As such, research and psychological interventions must be sensitive to the diversity of this population. Research that treats GLB youths as a single group and fails to examine variation within GLB youths (e.g., studies contrasting GLB with heterosexual youths) will not provide insights into how some GLB youths are resilient and well-adjusted. Similarly, psychological interventions applied indiscriminately to GLB youths may not prove as effective as interventions tailored to the specific needs of various GLB youths.

Limitations

The present research has limitations. The study is limited in that we could not assess and control for pre-suicidal psychological distress. Such an ideal project would require a prospective and longitudinal study beginning when youths enter puberty (i.e., when they begin to undergo sexual identity development). However, the current study does provide a preliminary examination of the long-term effects of suicidality on the psychological distress of GLB youths. The finding that a history of suicidality was associated with changes in psychological distress over time provides justification for further research in this area.

The strength of the relation between past suicidality and subsequent psychological distress is attenuated by time. Although some of the youths’ suicide attempts occurred very recently, others occurred a number of years prior to the study. Unfortunately, we could not examine whether time since last attempt or ideation affected the strength of the relation between suicidality and subsequent psychological distress because time since suicidality does not apply to youths who neither attempted nor ideated (our comparison group). Nevertheless, the fact that a relation was demonstrated between past suicidality and subsequent psychological distress, despite the passage of time, strengthens our argument that GLB youths who attempt suicide may have long-term psychological distress.

The sample is modest in size. However, we retained a substantial percentage of the sample over time. Data analysis was sensitive to the modest sample size in that a select number of factors were investigated. Of course, we encourage other researchers to examine our hypotheses with larger samples. In addition, sampling biases are possible and generalizability of findings may be limited because the recruitment of youths was nonrandom. Although youths were recruited from various organizations as a way of reducing sampling bias, we are aware that the sample is urban and includes youths participating in social programs at gay-focused community-based and college organizations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by center grant P50-MH43520 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Margaret Rosario, Principal Investigator, HIV Risk and Coming Out Among Gay and Lesbian Adolescents, Anke A. Ehrhardt, Principal Investigator, HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies.

Footnotes

As individuals may experience both supportive relationships and negative relationships with others, research has conceptualized social support and negative relationships as separate constructs and found that they are only moderately correlated (e.g., Revenson et al., 1991; Schrimshaw, 2002; Siegel et al., 1997).

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the biannual meeting of the European Association for Research on Adolescence, Oxford, UK, September 2002; and, at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, San Francisco, CA, November 2003.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III-R. 3. Rev. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Social Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Risk factors for serious suicide attempts among youths aged 13 through 24 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1174–1182. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boergers J, Spirito A. The outcome of suicide attempts among adolescents. In: Spirito A, Overholser JC, editors. Evaluating and treating adolescent suicide attempters: From research to practice. San Diego: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. The approval motive: Studies in evaluative dependence. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Suicidality patterns and sexual orientation-related factors among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2001;31:250–264. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.3.250.24246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner AH, Cranston K. Correlates of same-sex sexual behavior in a random sample of Massachusetts high school students. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:262–266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Childhood circumstances, adolescent adjustment, and suicide attempts in a New Zealand birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:612–622. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Wissow LS, Woods ER, Goodman E. Sexual orientation and risk of suicide attempts among a representative sample of youth. Arch Pediatric Adolesc Med. 1999;153:487–493. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granboulan V, Rabain D, Basquin M. The outcome of adolescent suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1995;91:265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley DN. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Kentucky; Lexington, KY: 1990. The context of well-being after significant life stress: Measuring social support and obstruction. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. The psychology of sexual prejudice. Cur Direct Psychol Sci. 2000;9:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Dev Psychol. 1995;31:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW, D’Augelli AR. Predictors of suicide attempts among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. J Adolesc Res. 1997;12:477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent A, Foussard N, David M, Boucharlet J, Bost M. A 5-year follow-up study of suicide attempts among French adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:424–430. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:297–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholser JC, Adams DM, Lehnert KL, Brinkman DC. Self-esteem deficits and suicidal tendencies among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:919–928. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, Klerman GL, Hurt SW, Kakuma T, Peskin JR, Siefker CA. Suicidal children grow up: Rates and psychosocial risk factors for suicide attempts during follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:106–113. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. Am J Community Psychol. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Windle M. Adolescent suicidal behaviors as a function of depression, hopelessness, alcohol use, and social support: A longitudinal investigation. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:329–354. doi: 10.1007/BF02506948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G, French S, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum R. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: Results of a population based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:57–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA, Schiaffino KM, Majerovitz D, Gibofsky A. Social support as a double-edged sword: The relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Social Sci Med. 1991;33:807–813. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90385-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1294–1300. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. J Community Psychol. 1996;24:136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Hunter J, Rosario M. Suicidal behavior and gay-related stress among gay and bisexual male adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 1994;9:498–508. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rosario M, Van Rossem R, Reid H, Gillis R. Prevalence, course, and predictors of multiple problem behaviors among gay and bisexual male adolescents. Dev Psychol. 1995;31:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Heimberg RG. Depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and related factors in sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:859–866. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Suicide attempts among sexual-minority youths: Population and measurement issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:983–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SG, Farberow NL, Kruks GN. Suicidal behavior in adolescent and young adult gay men. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 1989;19:381–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW. Social support, conflict, and integration among women living with HIV/AIDS. J Appl Social Psychol. 2002;32:2022–2042. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould M. Study of completed suicides in adolescents: Progress report. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shagle SC, Barber BK. Effects of family, marital, and parent-child conflict on adolescent self-derogation and suicidal ideation. J Marriage Fam. 1993;55:964–974. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Raveis VH, Karus D. Illness-related support and negative network interactions: Effects on HIV-infected men’s depressive symptomatology. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25:395–420. doi: 10.1023/a:1024632811934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Anderson R. Social support, risk-level and safety actions following acute assessment of suicidal youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29:451–465. [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D. Adolescent suicide attempters: Post-attempt course and implications for treatment. Clin Psychol Psychotherapy. 2000;7:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Plummer B, Gispert M, Levy S, Kurkjian J, Lewander W, et al. Adolescent suicide attempts: Outcomes at follow-up. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62:464–468. doi: 10.1037/h0079362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrom L. Predictors of adolescent suicide attempts: A nationally representative longitudinal study of Norwegian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:603–610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Fegan MF. Social networks and social support. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]